Waukesha Biota

The Waukesha Biota (also known as Waukesha Lagerstätte, Brandon Bridge Lagerstätte, or Brandon Bridge fauna) refers to the biotic assemblage of the Konservat-Lagerstätte of Early Silurian (Telychian to Sheinwoodian) age within the Brandon Bridge Formation in Waukesha County and Franklin, Milwaukee County, Wisconsin.[1] It is known for the exceptional preservation of its diverse, soft-bodied and lightly skeletonized taxa, including many major taxa found nowhere else in strata of similar age.[2]

| Waukesha Biota Stratigraphic range: Telychian-Sheinwoodian ~438–433 Ma | |

|---|---|

| Type | Konservat-Lagerstätte |

| Unit of | Brandon Bridge Formation |

| Area | Two quarries 32 km (20 mi) apart |

| Thickness | 12 cm (4.7 in) |

| Lithology | |

| Primary | Finely laminated interbedded mudstone |

| Other | Dolostone |

| Location | |

| Coordinates | 43°00′42″N 88°13′54″W |

| Region | Waukesha County and Franklin, Milwaukee County, Wisconsin |

| Country | |

| Extent | Very localized |

| Type section | |

| Named for | Waukesha County, Wisconsin; not to be confused with the Waukesha Formation, which overlies the Brandon Bridge Formation |

History and significance

Prior to the discovery of the Waukesha Biota, very little was known about the soft-bodied animals that were sure to have lived in the Silurian seas. Thanks to the famous Burgess Shale of the Canadian Rockies, we knew that the seas were already teeming with soft-bodied and lightly skeletonized animals as far back as the Cambrian, yet relatively few were known to be preserved in later Paleozoic rocks. This is because the fossil record is greatly skewed toward biomineralized skeletal remains. The announcement of the Waukesha Biota in 1985 thus marked a major turning point in our knowledge of Silurian life. In his popular book, Wonderful Life, Stephen Jay Gould compared the "anatomical disparity" of the Burgess Shale with that of only five other occurrences in the world –one of which was the Waukesha Biota, which he referred to as the "Brandon Bridge fauna"– and none of the others were Silurian.[3] Other “soft-bodied” Silurian sights have turned up in more recent years, but none have produced the high diversity of soft-bodied animals observed in this biota.[4][5] The exceptional preservation of the fossils of the Waukesha Biota thus provides a window to a significant portion of Silurian life that otherwise may have been undetected and therefore unknown to science.[6]

Stratigraphy and depositional environment

Most of the Waukesha Biota is preserved within a 12 centimetres (4.7 in) layer of thinly-laminated, fine-grained, shallow marine sediments of the Brandon Bridge Formation consisting of mudstone and dolostone deposited in a sedimentary trap at the end of an erosional scarp over the eroded dolostones of the Schoolcraft and Burnt Bluff Formations. A separate thin bed containing the biota is also present about 60 centimetres (24 in) above the 12 centimetres (4.7 in) interval. Fossils of unambiguous, fully terrestrial organisms are lacking from the Waukesha Biota.[1][7] Most of the Waukesha Biota fossils were found at a quarry in Waukesha County, Wisconsin, owned and operated by the Waukesha Lime and Stone Company. Other fossils were collected from a quarry in Franklin, Milwaukee County, owned and operated by Franklin Aggregate Inc. That quarry lies 32 kilometres (20 mi) south of the Quarry in Waukesha. The Franklin fossils were from blasted material apparently originating from a horizon and setting equivalent to that of the Waukesha site. Its biota is similar to that from the Waukesha site, except that it lacks trilobites.[5]

Taphonomy

The Waukesha Biota is unusual in preserving few of the kinds of animals that typically dominate the Silurian fossil record, including in other strata of the same two quarries. Fossils of corals, echinoderms, brachiopods, bryozoans, gastropods, bivalves, and cephalopods are rare or absent from the Waukesha Biota, although trilobites are diverse and common.[1][5]

The exceptional preservation of non-biomineralized and lightly skeletonized remains of the Waukesha Biota is generally attributed to a combination of favorable conditions, including the transportation of the organisms to a sediment trap that was hostile to predators but favorable to the production of organic films that coated the surfaces of the dead organisms, which inhibited decay, sometimes enhanced by promoting precipitation of a thin phosphatic coating, which is observed on many of the fossils.[1][2][8][9][7][5]

Biota

Green algae

Carbonized fossils of a noncalcified dasycladalean alga have been found at the Waukesha site and given the name Heterocladus waukeshaensis.[10]

Arthropods

The fossil record of the Waukesha Biota is dominated by arthropods, both in number of fossils and number of species.[4] This is even true when excluding trilobites, which in most Early Paleozoic marine biotas are the source of the vast majority or all of the arthropod fossils. This is due to preservational conditions which protect soft and lightly skeletonized tissues from decomposition but select against preservation of biomineralized skeletal remains.[1][5]

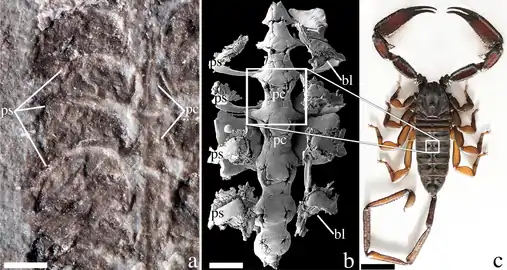

Scorpions

Two well preserved fossils of a chelicerate have been identified as a scorpion and named Parioscorpio venator, which if correctly identified is the oldest scorpion in the fossil record. One of the fossils preserves internal organs, including structures interpreted to be pulmo-pericardial sinuses; however, it is not certain whether the animal was marine, terrestrial or amphibious.[7]

Xiphosures

Well preserved fossils of another chelicerate that is also part of this biota belong to the Xiphosura (the group that includes horseshoe crabs). This species was named Venustulus waukeshaensis.[1][8]

Thylacocephalans

Thylacares brandonensis has been named for what is recognized as the oldest unequivocal thylacocephalan, which is an enigmatic group of crustaceans having a pair of raptorial appendages and a bivalved shield that encloses most of the body.[1][11]

Phyllocarids

Three species of phyllocarid crustaceans are part of the Waukesha Biota, consisting of Ceriatocaris macroura, C. papilio, and C. pusilla. Although these bivalved crustaceans are not new to science, their fossils preserve the delicate appendages and further show the diversity of the lightly biomineralized fossils of the Waukesha Biota.[2]

Cheloniellids

Common in the Waukesha Biota is an arthropod that has a pair of large raptorial appendages.[1] It has been identified as a new and the best preserved member of the enigmatic arthropod group known as the cheloniellida.[5] Although the taxon was given a name, the manuscript has not yet been peer reviewed, and the name is therefore not officially recognized.

Myriapods

Several fossils appearing to be myriapods (the group that includes millipedes and centipedes) are part of the Waukesha Biota.[5]

Other arthropods

Other kinds of arthropods having varying degrees of biomineralization of their skeletal elements are also present in the Waukesha Biota, including leperditicopid ostracods (crustacea), and about thirteen species of trilobites, several of which are new. Some trilobite taxa preserve their digestive tracts. An unnamed dalmanitid is commonly found with its dorsal exoskeleton intact and sometimes seen in such numbers that they cover large surfaces of sediment.[1][5]

Some taxa do not readily fit within existing arthropod groups, such as the very common “butterfly animal,” which appears to have two wing-like extensions at its sides, but may be another enigmatic bivalved arthropod.[1][5]

Pulmonary-cardiovascular structures of Parioscorpio compared with those of modern scorpion

Pulmonary-cardiovascular structures of Parioscorpio compared with those of modern scorpion

Dalmanitid trilobite; the most common trilobite of the Waukesha Biota

Dalmanitid trilobite; the most common trilobite of the Waukesha Biota The styginid trilobite Meroperyx

The styginid trilobite Meroperyx

Anomalocarid?

The grasping appendage of what is questionably attributed to an anomalocarid was found among the Waukesha Biota material. [12] If this identification proves accurate, the specimen would be the first occurrence of an anomalocarid to be found in the Silurian.[13]

Lobopods

Several unnamed species of lobopods (worm-like animals with annulated appendages) are known from the Waukesha Biota.[1][12] One of these was originally thought to be a myriopod arthropod until further study revealed key lobopod characteristics.[9]

"Worms"

Many exquisitely preserved vermiform fossils, some preserving digestive tracts, are part of the Waukesha biota. These include annelids, such as an aphroditid polychaete, a spiny polychaete, and an annelid that appears to have a sucker disc at one end. If this proves to be a leech, it would be the first unequivocal fossil leech ever recorded. Another worm-like taxon in the biota is identified as a palaeoscolecid.[1][5] Scolecodonts, which are the jaws of polychaete worms, have also been found in this biota.[1]

Hemichordates

Several genera of the hemichordates known as graptolites, including Oktavites, Desmograptus, Dictyonema, and Thallograptus?, are reported from this biota.[1][5]

Chordates

A fossil of the conodont animal, the primitive, eel-like chordate now known to be the source of certain small, phosphatic, tooth-like structures long-used in the dating of strata and now known as "conodont elements," has also been found. An assemblage of conodont elements were found associated with this fossil. The Waukesha Biota was only the second occurrence to produce a conodont animal.[1][14][15] Numerous, well-preserved chordate fossils that may also be conodont animals were later found in the Waukesha Biota at Franklin Quarry.[5]

Other animal taxa

The Waukesha Biota includes fossils of many fragmentary, unidentifiable, nonbiomineralized and lightly biomineralized skeletal elements that may belong to additional taxa. It also includes fossils of conulariids and certain biomineralized taxa that are common in typical Silurian marine occurrences, but are rare or uncommon here, including tabulate corals, brachiopods, cephalopods, and echinoderms.[1][5]

References

- Mikulic, D.G.; Briggs, D.E.G.; Kluessendorf, J. (1985). "A new exceptionally preserved biota from the Lower Silurian of Wisconsin, U.S.A." Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society of London B. 311: 75–85.

- Jones, W.T.; Feldman, R.M.; Schweitzer, C.E. (2015). "Ceratiocaris from the Silurian Waukesha Biota, Wisconsin". Journal of Paleontology. 89 (6): 1007–1021. doi:10.1017/jpa.2016.22.

- Gould, S.J. (1989). Wonderful Life: The Burgess Shale and the Nature of History. New York: W.W. Norton & Company. ISBN 978-0-393-30700-9.

- Kluessendorf, J. (1994). "Predictability of Silurian Fossil-Konservat-Lagerstätten in North America". Lethaia. 27 (4): 337–344. doi:10.1111/j.1502-3931.1994.tb01584.x.

- Wendruff, A.J.; Babcock, L.E.; Kluessendorf, J.; Mikulic, D.G. (2020). "Paleobiology and Taphonomy of exceptionally preserved organisms from the Waukesha Biota (Silurian), Wisconsin, USA". Palaeogeography, Palaeoclimatology, Palaeoecology. 546.

- Gass, K.C. (2008). "The Waukesha Biota: A unique window to the Silurian world". Fossil News. 14 (12): 7.

- Wendruff, A.J.; Babcock, L.E.; Wirkner, C.S.; Kluessendorf, J.; Mikulic, D.G. (2020). "A Silurian ancestral scorpion with fossilised internal anatomy illustrating a pathway to arachnid terrestrialisation". Scientific Reports. 10 (14): 14. doi:10.1038/s41598-019-56010-z. PMC 6965631. PMID 31949185.

- Moore, R.A.; Briggs, D.E.G.; Braddy, S.J.; Anderson, L.I.; Mikulic, D.G.; Kluessendorf, J. (2005). "A new synziphosurine (Chelicerata: Xiphosura) from the Late Llandovery (Silurian) Waukesha Lagerstätte, Wisconsin, USA". Journal of Paleontology. 79 (2): 242–250. doi:10.1666/0022-3360(2005)079<0242:ANSCXF>2.0.CO;2.

- Wilson, H.M.; Briggs, D.E.G.; Mikulic, D.G.; Kluessendorf, J. (2004). Affinities of the Lower Silurian Waukesha 'Myriapod'. 2004 annual meeting of the Geological Society of America.

- LoDuca, S.T.; Kluessendorf, J.; Mikulic, D.G. (2003). "A new noncalcified dasycladalean alga from the Silurian of Wisconsin". Journal of Paleontology. 77 (6): 1152–1158. doi:10.1666/0022-3360(2003)077<1152:ANNDAF>2.0.CO;2.

- Haug, C.; Briggs, D.E.G.; Mikulic, D.G.; Kluessendorf, J.; Haug, J.T. (2014). "The implications of a Silurian and other thylacocephalan crustaceans for the functional morphology and systematic affinities of the group". BMC Evolutionary Biology. 14 (159): 1–15. doi:10.1186/s12862-014-0159-2. PMC 4448278. PMID 25927449.

- Wendruff, A.J. (2016). Paleobiology and Taphonomy of Exceptionally Preserved Organisms from the Brandon Bridge Formation (Silurian), Wisconsin, USA. Ph.D dissertation, Ohio State University.

- Giribet, G.; Edgecombe, G.D. (2019). "The phylogeny and evolutionary history of arthropods". Current Biology. 29 (12): 592–602. doi:10.1016/j.cub.2019.04.057. PMID 31211983.

- Smith, M.P.; Briggs, D.E.G.; Aldridge, R.J. (1987), "A conodont animal from the lower Silurian of Wisconsin USA and the apparatus architecture of panderodontid conodonts", in Aldridge, R.J. (ed.), Paleobiology of Conodonts, British Micropalaeontological Society Series Ellis Horwood, Chichester, pp. 91–104

- Knell, S.J. (2013). The Great Fossil Enigma: The Search for the Conodont Animal. Bloomington, IN: Indiana University Press. p. 413. ISBN 978-0-253-00604-2. JSTOR j.ctt16gh7mr.