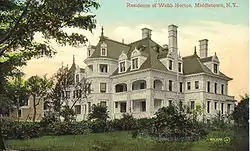

Webb Horton House

The Webb Horton House, is an ornate 40-room mansion in Middletown, New York, United States, designed by local architect Frank Lindsey. Built 1902-1906 as a private residence, since the late 1940s it has been part of the campus of SUNY Orange. This building is now known as Morrison Hall, after the last private owner, and houses the college's main administrative offices. A nearby service complex has also been kept and is used for classrooms and other college functions.

Webb Horton House | |

Partial south elevation, 2008 | |

| |

| Location | Middletown, NY |

|---|---|

| Coordinates | 41°26′19″N 74°25′33″W |

| Area | 5 acres (2.0 ha)[1] |

| Built | 1906[1] |

| Architect | Frank Lindsey |

| Architectural style | Various 19th and 20th century revival styles |

| NRHP reference No. | 90000690 |

| Added to NRHP | 1990 |

The mansion is an extravagant combination of styles and materials that has been altered very little during its ownership and use by the college. In 1990 it was listed on the National Register of Historic Places.

Building

The house sits on a low hilltop on South Street between East Conkling and Grand View avenues in the southwest quadrant of the city. It has a view to the southeast. The five-acre (2 ha) lot that was originally the mansion property is now part of the college campus, but it still has its original curvilinear road and path system as well as four contributing outbuildings. On the north (rear) of the house is its original 1.7-acre (6,900 m2) lawn, sloping gently down toward Wawayanda Creek behind the college. That lawn now serves as the college's main quad.[1]

The college campus surrounds the house on three sides, with a large modern building called Hudson Hall immediately to the east. A 6½-foot–high (2 m) stone and iron fence, ornamented with scrolls and the initials "WH" on the main gate, screens the house from South Street and the parking lots across it. Large, mature trees grow around the house. The neighborhood around the campus is residential.[1]

Exterior

The house has load-bearing walls sided in rock-faced marble tied into its steel frame. It is 118 feet (36 m) long and 80 feet (24 m) wide. It rises two stories above a high basement, with all windows protected by cast and wrought iron grilles, to steeply pitched hipped roofs surfaced in green ceramic tile and pierced by ornate dormer windows. Three-story towers rise on the front and rear facades.[1]

There are four separate sections to the front facade. At the south corner, the tower's three bays form a porch on the first story. On the two above, each bay has a pair of windows separated by a Corinthian pier. The conical roof has three dormers, each gabled, decorated with marble in a shell motif and topped with a finial. They contain one window flanked by pilasters.[1]

The porch continues onto the main facade's two bays. On the first floor, the northern bay serves as the main entrance. It is topped with a carved cartouche consisting of the WH monogram, ribbons, fruits and oak leaves. The door is flanked with marble panels carved with vases, foliage and bellflowers. The windows have a Corinthian column at each side and egg-and-dart molded lintels. The porch is floored in a pale gray mosaic with a darker gray border.[1]

The second story of this section has three windows, each separated by Corinthian piers. Above it is a molded stone cornice and frieze, carved in foliage and flowers, which extends around the towers. The windows are complemented by two dormers similar to, but larger than, the tower dormers.[1]

The next three bays have a single window on the first and second story with cartouches at the lintels. Above the second story is a wide frieze with cornucopia, shells, torches, flowers and other foliage. At the third story is an open balcony. Its openings are similar to those on the first story's porch. Above it is a frieze similar to the one on the tower, a molded stone cornice, three dormers and a hipped roof with a conical top over the bay. A tall, paneled chimney marks the intersection of the conical and hipped roofs.[1]

The third section, two bays wide, has a similar treatment to the entrance section. Each bay has three windows, added later. The two dormers in the hipped roof are similar to those at the entrance.[1]

A terrace connects the southeast and northeast facades. It has a stone balustrade and other similar treatments to the porches on the southeast facade. Atop, a chimney rises from between two dormers.[1]

At the other end of the northeast facade, with fenestration similar to the rest of the house, is a flat-roofed balustraded porch, now enclosed. It has similar treatments to the doors and windows on the southeast facade.[1]

The northwest facade is as complex as the southeast. Its roofline is marked by four chimneys and dormers similar to the others. In the center is a projecting curved section, three bays wide, three and a half stories high, similar to the one opposite with a balcony. On the south of the facade is a porte cochère of marble, with opening treatments similar to the porches. At the top of its stairs is an iron and glass vestibule with intricate carved cartouches, scrolls, foliage and circles. Above this entrance, on the second story, is a pictorial stained glass window attributed to the Tiffany studio.[1]

On the western corner, a terrace begins. It wraps around the corner to become a porch running the length of the southwest facade. Atop its entire length is a stone balustrade. Above it is a hipped roof with two chimneys, both flanked by dormers.[1]

Interior

All the stories still have their original central-hall interior plan. The main entrance leads into it via a paneled vestibule. The major rooms are off to the south, including the circular salon, linked to the stained oak library by pocket doors. Both incorporate many rococo relief designs.[1]

On the north side of the hall is a large carved wooden fireplace with onyx trim. A small room next to it leads to the dining room, with a beamed ceiling, and kitchen. On the west side, a short flight of stairs leads to the porte-cochère and a large mahogany stair to the second floor. The stained glass window lights the landing.[1]

The stairway ends in a curved balustrade on the second floor hall, done in Circassian walnut. This level was given over originally to bedrooms for the family and guests. The rooms in the tower were used as a solarium. The third floor hallway is more open and was, according to the Horton family, used as a ballroom. The large room to the south was originally a billiard room. Another bedroom was located to the north, with the top room in the tower serving as a trophy room. Its ceiling, right under the tower's conical roof, is ornamented with ribs and Moorish Revival relief designs.[1]

Outbuildings

A service complex enclosed by cobblestone walls is located to the northeast. The largest building is Horton Hall, an L-shaped garage/carriage house with upstairs apartment on the north of the complex. It is sided in large, irregularly cut masonry which may be artificial aggregate or lava stone. Its hipped roof, pierced with gabled dormers, is covered in flat green ceramic tile. Inside the first floor has been converted to office space, but it retains some of the original finishes.[1]

On the south end of the garage/stable is a corral for the horses. To the southwest is a one-story toolhouse similar to the garage. It was also used as an icehouse. Today it houses several transformers.[1]

South of Horton Hall is functioning glass greenhouse on stone foundation, a second greenhouse foundation was converted into classroom/lab space, now known as the Devitt Center for Botany and Horticulture. Between them is a pergola. There is also a small, sunken garden on the grounds of Horton Hall.

There was originally a sunken garden to the southwest of Morrison Hall, which is now the site of the Library. The stones from the old sunken garden are stacked on the Horton Hall grounds.

Aesthetics

The Webb Horton House is typical of the country seats built by the wealthy of late 19th-century America, though in an urban or suburban setting. It shows the influence of Artistic Country-Seats', an 1887 pattern book by George William Sheldon, which had houses with many different rooms.[1]

The building's massive form shows the influence of several contemporary architectural styles. The masonry exterior is a Richardsonian Romanesque touch, the complicated roofline is in accord with the Queen Anne Style, and the classically inspired decorations a nod to the Beaux-Arts mode.[1]

History

The mansion was designed by Frank J. Lindsey, a local carpenter turned architect, for Horton, a Delaware County native who had built a fortune starting from a Narrowsburg tanning business, later benefiting from an oil strike in Sheffield, Pennsylvania. The Horton family had been living in an older house on the property since the 1880s, slowly acquiring the land for the estate house.

Construction of the main building was begun in 1902, when Webb was 76, and completed in 1906, reportedly at a cost of a million dollars ($28.5 million in contemporary dollars[2]). Horton died in 1908, reportedly never having spent a night in the house.[3] His wife died two years later, and by 1918 both their children had died without marrying or otherwise leaving heirs.[1]

Before he succumbed to the flu in 1918, Eugene Horton, the last to die, had acquired the land for the service complex. He hired another local architect, David Hastings Canfield, to design the outbuildings. In addition to the current complex, there was a conservatory and hothouse on the site, as well as a frame house facing East Conkling. In 1911 the Horton children had bought the house at South and East Conkling, later tearing it down for the sunken garden.[1]

Eugene Horton willed the estate to his cousin and employee, John Morrison. Morrison, a farmer, reluctantly took care of the estate until his death in 1946.[3] He made few changes to the property.[1]

Morrison's will left the estate to Horton Hospital (also named after the house's first resident) in Middletown, with his wife Christine[3] granted life tenancy. When the founders of Orange County Community College approached her in the late 1940s, she was willing to sell, but did not have the legal right since her husband's will had already disposed of the property. The hospital was not willing to sell at that time since it had planned to do so upon Mrs. Morrison's death in the hope of getting the best possible price to pay down its debt. The community raised $480,000 ($5.1 million in contemporary dollars[2]) to that end, and the hospital released its claim.[1]

The first classes were held in 1950 in the garage/stable building, now called Horton Hall. While many more modern buildings have been developed on the campus, the mansion, stables, and other outbuildings are still used for educational, administrative, and custodial purposes. The college has made a few changes: converting one of the upper balconies to an office, enclosing the porches, and putting in new vestibule doors. Other than that, the buildings have retained their integrity.[1]

References

- Kuhn, Robert (March 13, 1990). "National Register of Historic Places nomination, Webb Horton House". New York State Office of Parks, Recreation and Historic Preservation. Retrieved November 22, 2009.

- Federal Reserve Bank of Minneapolis. "Consumer Price Index (estimate) 1800–". Retrieved January 1, 2020.

- Bedell, Barbara (January 16, 2007). "The Hortons, the Morrisons, and a mansion that became a SUNY centerpiece". Times Herald-Record. Ottaway Community Newspapers. Retrieved November 23, 2009.