Whistler Sliding Centre

The Whistler Sliding Centre (French: Centre des sports de glisse de Whistler) is a Canadian bobsleigh, luge, and skeleton track located in Whistler, British Columbia, that is 125 km (78 mi) north of Vancouver. The centre is part of the Whistler Blackcomb resort, which comprises two ski mountains separated by Fitzsimmons Creek. Located on the lowermost slope of the northern mountain (Blackcomb Mountain), Whistler Sliding Centre hosted the bobsleigh, luge, and skeleton competitions for the 2010 Winter Olympics.

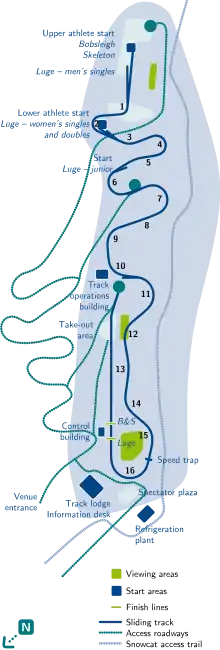

The Whistler Sliding Centre shown in June 2008. The refrigeration plant is shown behind turn 16. | |

| |

| Location | Whistler, British Columbia, Canada |

|---|---|

| Coordinates | 50°6′27″N 122°56′42″W |

| Owner | VANOC (2005 to 2010), Whistler 2010 Sports Legacies (since the end of the 2010 Winter Olympics) |

| Operator | VANOC (2005 to 2010), Whistler 2010 Sports Legacies (since the end of the 2010 Winter Olympics) |

| Capacity | 12,000[1] |

| Field size | (All from[1] Bobsleigh/ Skeleton: 1,450 m (4,760 ft) Luge – men's singles: 1,374 m (4,508 ft) Luge – women's singles/ men's doubles: 1,198 m (3,930 ft) Junior: 953 m (3,127 ft) |

| Surface | Reinforced concrete with ammonia refrigeration piping that is turned on to create 2 to 5 cm (0.79 to 1.97 in) of ice.[1] |

| Scoreboard | Yes |

| Construction | |

| Broke ground | 1 June 2005 |

| Built | 1 June 2005 to November 2007 |

| Opened | 19 December 2007 |

| Construction cost | C$105 million[1] |

| Architect | Stantec Architecture Limited[1] |

| Project manager | Heatherbrae[1] |

| Services engineer | Western Pacific Enterprises GP/ Cimco Refrigeration (Toromont Industries Limited)[1] |

| General contractor | Emil Anderson Construction Inc.[1] |

| Main contractors | Emil Anderson Construction Inc.[1] |

Design work started in late 2004 with construction taking place from June 2005 to December 2007. Bobsledders Pierre Lueders and Justin Kripps of Canada took the first run on the track on 19 December 2007. Certification took place in March 2008 with over 200 runs from six different start houses (the place where the sleds start their runs), and was approved both by the International Bobsleigh and Tobogganing Federation (FIBT) and the International Luge Federation (FIL). Training runs took place in late 2008 in preparation for the World Cup events in all three sports in early 2009. World Cup competitions were held in February 2009 for bobsleigh, luge, and skeleton. The top speed for all World Cup events set by German luger Felix Loch at 153.98 km/h (95.68 mph). In late 2009, more training took place in preparation for the Winter Olympics.

On 12 February 2010, the day of the Olympic opening ceremonies, Georgian luger Nodar Kumaritashvili was killed during a training run while reportedly going 143.3 km/h (89.0 mph). This resulted in the men's singles event being moved to the women's singles and men's doubles start house while both the women's singles and men's doubles event were moved to the junior start house. During actual luge competition at the 2010 Winter Olympics, there were only two crashes, which resulted in one withdrawal. Skeleton races on 18–19 February had no crashes though two skeleton racers were disqualified for technical reasons. Bobsleigh competitions had crashes during all three events. This resulted in supplemental training for both the two-woman and the four-man event following crashes during the two-man event. Modifications were made to the track after the two-man event to lessen the frequency of crashes as well. A 20-page report was released by the FIL to the International Olympic Committee (IOC) on 12 April 2010 and to the public on FIL's website on 19 April 2010 regarding Kumaritashvili's death. Safety concerns at Whistler affected the track design for the Sliding Center Sanki that was used for the 2014 Winter Olympics in Sochi. This included track simulation and mapping to reduce top speeds by 6 to 9 km/h (3.7 to 5.6 mph) for the Sochi track.

Constructed on part of First Nations spiritual grounds, the track won two provincial concrete construction awards in 2008 while the refrigeration plant earned Canada's Leadership in Energy and Environmental Design "gold" certification two years later.

History

Awarding and construction (2004–07)

At the 115th IOC Session held at Prague in 2003, Vancouver was chosen to host the 2010 Winter Olympics over Pyeongchang, South Korea, and Salzburg, Austria.[2] On 15 November 2004, it was announced that Stantec Architecture Limited, which designed the 2002 Winter Olympic bobsleigh, luge, and skeleton track in Park City, Utah, in the United States, would provide detail design and site master plan of the track.[3] The company was advised by the German track engineering firm IBG.[3][4] IBG had designed the tracks used in Oberhof, Germany, the 1988 Winter Olympics in (Calgary) and the 2006 Winter Olympics (Cesana Pariol).[4] The German firm is also the designer of the Russian National Sliding Centre, the venue for the 2014 Winter Olympics in Sochi.[4]

Site construction of the facility began on 1 June 2005 following environmental approval under the Canadian Environmental Assessment Act.[5][6] Safety and security was then put in place on the site.[6] During its peak of construction activities in the summer of 2006, more than 500 workers were involved both at the Sliding Centre and at the Whistler Nordic Venue (now Whistler Olympic Park).[7] A core group of 60 workers was involved with track construction from June 2005 to December 2007.[8] Basic track construction was completed in November 2007 though fit-out and testing continued into 2008.[9]

First testing and certification (2007–08)

The first run was on 19 December 2007 with Canadian bobsledder Pierre Lueders and his brakeman Justin Kripps starting at the Junior Start house (Location where the sliders start their run on the track) 520 m (1,710 ft) down the 1,450 m (4,760 ft) track.[10][11] A total of six runs were made under the auspices of the FIBT.[10] The Canadian Luge Association opened a branch at the track in February 2008.[12] Luge tests occurred in late February 2008 and among the participants were Tatjana Hüfner (Germany), Erin Hamlin (United States), Armin Zöggeler (Italy), and Regan Lauscher (Canada).[12][13] Bobsleigh participants during certification in March 2008 included Sandra Kiriasis (Germany), Lueders (Canada), and Shauna Rohbock (United States) while skeleton participants included Kristan Bromley (Great Britain), Kerstin Jürgens (Szymkowiak since summer 2008 – Germany), and Jon Montgomery (Canada).[14] Over 200 runs were taken from six different starting positions on the track.[15]

Praise was given both by the FIBT and the FIL over the successful certification of the track.[15] The Vancouver Organizing Committee (VANOC) reviewed the recommendations made from both the FIBT and the FIL to fine tune the track.[15] Canadian teams continued testing and training at the track until 20 March 2008.[15] A total of 2155 runs (335 bobsleigh, 1077 luge, and 743 skeleton) took place at the track with a total of 15 crashes.[16] Final track inspection by the FIL Executive Board took place 25–27 September 2008 before the International Training Week later that year.[17]

2008–09 Luge World Cup, including training

International Training Week for luge took place at the track 7–15 November 2008.[16][18] A total of 2482 runs took place during the training with several injuries occurring, most notably Loch, the 2008 men's singles world champion, who injured his shoulder.[19] In a 9 December 2008 press release, the Centre was continuing certification by adding protections on the track against crashes and weather.[20] FIL President Josef Fendt stated that the track's speed was too high with top speeds reaching 149 km/h (93 mph) during training.[21] From the 2482 runs executed during the International Training week for luge, there were 73 crashes, a crash rate of three percent which was normal during new track testing.[21] Three lugers, including Loch, were sent to the hospital, but were later released.[21] Italy's Zöggeler stated that "The track can be tackled." and "does not see big problems for the athletes" while Fendt called for the top track speed for future tracks to be lowered to 135 or 136 km/h (84 or 85 mph) where possible.[21] For the 2008–09 World Cup season at the Centre, 15115 runs were made for bobsleigh (2153), luge (9672), and skeleton (3290).[16] After the World Cup event on 20–21 February 2009, Austria's Andreas Linger described the track as "fast, incredibly fast."[22]

Loch stated that luge speeds for men's singles reached 100 km/h (62 mph) before turn three at the women's singles and men's doubles' start house.[22] A total of 2818 runs for bobsleigh, luge, and skeleton were made at the track during the four-week time period for the World Cup events.[23] FIL President Fendt stated that "[my] technical delegate told me this week that the Games could start tomorrow and the track would be ready." and he appreciated the whole Whistler Sliding Centre[23] At the 2008–09 World Cup season finale, 135 athletes participated (67 men, 42 women, and 26 doubles) though 144 athletes from 23 nations were registered.[16][23] During the Luge World Cup event that weekend, 186 runs took place with 16 crashes.[16]

2008–09 Bobsleigh and Skeleton World Cup and training

The first bobsleigh and skeleton training week took place on 25–31 January 2009 to prepare for their respective World Cup events on 5–7 February 2009.[24] A total of 250 competitors from 24 nations took part in the World Cup practice for all five events (Bobsleigh two-man, bobsleigh two-woman, bobsleigh four-man, and men's and women's skeleton).[25] Competition and weather affected testing and World Cup runs for the two-week time period.[25] A team of 118 personnel and 276 volunteers worked consecutive weeks at the Training Week and World Cup events.[25] Track director Craig Lehto stated that the volunteer efforts were similar to what he had seen both at the 2002 Winter Olympics in Salt Lake City and the 1988 Winter Olympics in Calgary.[25] The final two days of competition had 3000 total spectators.[25] Medical services, led by VANOC and FIBT medical director Dr. David McDonagh, tested themselves with first responder care and mock scenarios that included athlete extraction from the sled if the accident was severe enough.[25] These services were tested again during the Luge World Cup competition on 20–21 February 2009.[25] A total of 15,000 spectators attended all five days for the bobsleigh, luge, and skeleton World Cup events, all sold out.[23] FIBT President Robert H. Storey stated that the Centre "... is fast, technical, demanding, and interesting.".[23] A total of 235 athletes participated in the 2008–09 World Cup event (92 four-man, 54 two-man, 40 two-woman, 28 men's skeleton, and 21 women's skeleton).[23]

2009–10 World Cups, including training

A paid training session took place 27 October – 7 November 2009 at the Centre for bobsleigh teams in preparation for the 2010 Games.[26] On 9–15 November 2009, a second International Training Week for luge took place in preparation for the 2010 Games with the participation of 156 athletes from 27 nations.[27][28] Venezuela's Werner Hoeger was knocked unconscious during a practice run on 13 November 2009 and was denied any further make-up runs.[29] During training that week, Hoeger expressed concern about the safety of the track.[29] These concerns called for the resignation of track director Ed Moffat, father of lugers Chris and Mike, to offer equal runs to all lugers in future events, to have Canada forfeit any extra training runs that were negotiated for the 2014 Winter Olympics, and for the Canadian Luge Association be reprimanded for unethical actions and not providing a safe sliding environment, especially after speeds were 10 mph (16 km/h) higher than expected.[29] Canadian Luge Association officials declined to comment though they stated to the New York Times that the lugers received up to three times the amount of training runs offered in the run-up to the 2006 Winter Olympics at Cesana Pariol.[29]

Team Canada (luge) did not participate in the World Cup event in Lillehammer, Norway during 12–13 December 2009 to train at the Sliding Centre and to compete at the Canadian National Championships that took place on 17 December 2009.[30] A training restriction went into effect on 31 December 2009 where only host nation Canada and athletes from developing nations were allowed to train before the 2010 Games.[28] For the 2009–10 season, there were a total of 15736 runs among bobsleigh (2512), luge (8794), and skeleton (4070) with a total of 115 crashes among the three sliding disciplines.[16]

Public opening and post-Olympic usage

The Centre's official website was launched in late June 2008.[31] Public self-guided walking tours ran from 3 July through 31 August 2008.[32][33] The cost to the public was 5 Canadian dollars (C$5) with children under 12 admitted free.[33] World Cup competition for bobsleigh and skeleton took place on 2–8 February 2009 while luge took place on 20–21 February 2009.[22][24] The track was a finalist for the 2012 FIL World Luge Championships along with Altenberg, Germany, at the 2008 FIL Congress in Calgary, Alberta, but the track withdrew its bid before 28 June 2008 selection.[34][35] During a 4–5 April 2009 weekend meeting of the FIL Commission at St. Leonhard, Austria, it was recommended that the Centre be host for the 2013 FIL World Luge Championships.[36] This was confirmed on 19–20 June 2009 at the 57th FIL Congress meeting in Liberec, Czech Republic.[37]

Post-Olympic usage is a responsibility of the Whistler 2010 Sports Legacies which operates the Sliding Centre, Whistler Olympic Park, and the Whistler Olympic and Paralympic Village.[38] The goal of this organization is to promote the legacy of the 2010 Winter Olympics and 2010 Winter Paralympics, promote healthy lifestyles and tourism in the British Columbia province, and offer revenue for the maintenance of the three facilities.[39]

Championships hosted

- 2010 Winter Olympics

- IBSF World Bobsleigh and Skeleton Championships: 2019

- FIL World Luge Championships: 2013

- Bobsleigh World Cup: 2008–09, 2010–11, 2011–12, 2012–13, 2015–16, 2016–17, 2017–18,

- Skeleton World Cup: 2008–09, 2010–11, 2011–12, 2012–13, 2015–16, 2016–17, 2017–18

- Luge World Cup: 2008–09, 2011–12, 2013–14, 2016–17, 2018–19, 2019–20

2010 Winter Olympics

Nodar Kumaritashvili

On 12 February 2010, hours before the opening ceremony for the 2010 Winter Olympics, Georgian luger Nodar Kumaritashvili suffered a crash during a training run exiting out of turn 16.[40] Kumaritashvili was injured when he flew off the track and collided with a steel pole.[41][42] He was going 143.3 km/h (89.0 mph) at the time of the crash.[41] He died later that day from the injuries sustained in that crash.[43] His accident came after other crashes during that week.[43] This reignited concerns about the track's safety.[43] Kumaritashvili was the first Olympic athlete to die at the Winter Olympics in training since 1992 and the first luger to die in a practice event at the Winter Olympics since Kazimierz Kay-Skrzypeski of Great Britain was killed at the luge track used for the 1964 Winter Olympics in Innsbruck.[44] It was also luge's first fatality since 10 December 1975 when an Italian luger was killed.[45] A joint statement was issued by the FIL, the IOC, and VANOC over Kumaritashvili's death.[46] Training was suspended for the rest of that day.[46][47] According to the Coroners Service of British Columbia and the Royal Canadian Mounted Police, Kumaritashvili's death was an accident caused by a "convergence of several factors", including the high speed of the track, its technical difficulty, and the athlete's relative unfamiliarity with the track.[48]

As a preventive measure, an extra 100 ft (30 m) of wall was added after the end of Turn 16, and the ice profile was changed. Also, the men's singles luge event start was moved from its start house to the one for both the women's singles and men's doubles event.[49] Women's singles and men's doubles start was moved to the Junior start house of the track, located after turn 5.[50] Germany's Natalie Geisenberger complained that it was not a women's start but more of a Kinder ("children" in (in German)) start. Her teammate Hüfner, who had the fastest speed on the two practice runs at 82.3 mph (132.4 km/h), stated that the new start position "does not help good starters like myself."[50] American Erin Hamlin, the 2009 women's singles world champion, stated the track was still demanding even after the distance was lessened from 1,193 to 953 m (3,914 to 3,127 ft) and one was still hitting 80 mph (130 km/h).[50]

During a 14 February 2010 interview with Reuters, FIL Secretary-General Svein Romstad stated that the federation considered cancelling the luge competition in the wake of Kumaritashvili's death two days earlier.[51] Romstad stated that "[Kumaritashvili] ... made a mistake" on the crash though "any fatality is unacceptable".[51] Additionally, Romstad stated that the start houses were moved to their current locations "mostly for an emotional reason".[51] Because of Kumaritashvili's death, the FIL worked with the Sochi 2014 Olympic Organizing Committee to make the Russian National Sliding Centre in Rzhanaya Polyana slower in speed.[51] Canada's Alex Gough commented on 14 February (two days after Kumaritashvili's death) that "We’ve got the world championships here in a few years (2013) so hopefully we can actually have a race" instead of the start at the Junior start house.[52]

On 18 February 2010, FIL President Fendt issued the following statement:

"At the conclusion of the luge competition at the Vancouver 2010 Olympic Games, our thoughts are with the family of Nodar Kumaritashvili. We again offer our heartfelt condolences to them, to his friends and to the entire Georgian Luge Federation. Nodar Kumaritashvili will forever stay in the hearts of all the members of the Luge family.

This has also been a difficult time for the Olympic athletes who competed in these Games. Their solidarity and sportsmanship was a tribute to the friend we lost. The International Luge Federation is touched by the outpouring of compassion and sympathy from people around the world. We will leave Whistler determined to do all we can to prevent a recurrence of this tragic event."[53]

Kumaritashvili was buried in his hometown of Bakuriani, on 20 February 2010.[54] Georgian National Olympic Committee president Gia Natsvlishvili and Georgia president Mikheil Saakashvili raised concern and anger toward the Sliding Centre's organizers that the safety concerns were not addressed.[54]

Luge

On 11 February 2010, Romania's Violeta Strămăturaru was knocked unconscious after hitting several walls during a training run.[55] She was strapped to a backboard and placed on a stretcher though her arms were moving.[55] Strămăturaru withdrew before the women's singles event.[56]

In the first run of the men's doubles luge competition on 17 February 2010, Austria's team of Tobias Schiegl and Markus Schiegl survived a crash on turn 16 where they came in at too high of an elevation. Tobias tried to correct the oversteer only to have the cousins collide on the opposite side of the ice wall, causing both to go airborne momentarily. Neither suffered any injury.[57]

Mihaela Chiras of Romania suffered the only crash of ten actual competitive runs (four men single, four women single, and two doubles), and that was during the second run of the women's singles event.[58] Each of the five days of luge competition was attended by a sold-out crowd of 12,000 spectators.[58]

Event winners were Germany's Loch in men's singles,[59] Germany's Hüfner in women's singles,[56] and Austria's Andreas and Wolfgang Linger in doubles.[60]

Skeleton

The first skeleton practice began down the full length of the track on 15 February 2010.[61] It was the first time that had been done since Kumaritashvili's death three days earlier.[61] Britain's Shelley Rudman stated that "The IOC and VANOC have done all they can to make it a safe environment".[61] Canada's Mellisa Hollingsworth had the fastest women's practice runs while her teammate Montgomery had the fastest men's practice runs.[61] Montgomery and Hollingsworth also had the fastest practice times on both the 16th and the 17th.[62][63] No crashes occurred during the two days of skeleton competitions.[64][65]

Event winners were Montgomery in the men's and Britain's Amy Williams in the women's.[64][65]

Bobsleigh

Bobsleigh practice began on 17 February 2010 with the two-man event. Eight crashes among 57 runs took place that day.[66] Three crashes occurred during the two-man practice session on 18 February 2010.[67] Supplemental practice was offered on 19 February 2010 to both the two-woman and four-man events out of caution, and further preparation for both events that took place the following week.[68]

For the first run on 20 February 2010, a sled from Australia crashed out and did not finish, while a sled from Great Britain was disqualified when the sled's brakeman was ejected during the first run.[69] Liechtenstein's sled crashed out during the first run and finished, but did not start the second run.[69] During the two-man event, runs three and four on 21 February 2010 were rescheduled to 16:00 PST (00:00 UTC on 22 February) for run three and 17:35 PST (01:35 UTC on the 22nd) for run four due to unseasonable warm weather.[70] Temperatures reached 10 °C (50 °F) on the afternoon of the 20th and were expected to reach 12 °C (54 °F) on the afternoon of the 21st.[70] No crashes occurred in the final two runs of the event.[71] Germany's André Lange and Kevin Kuske won the two-man event.[72]

Reactions from bobsledders about the track during the two-man event varied from exciting to anxious to dangerous.[73] The Associated Press spoke to 13 of the 21 drivers who competed at the two-woman event on 23–24 February 2010 and the only one who did not feel safe on the track was Erin Pac of the United States.[73] The three German drivers who competed in the two-woman event stated through a team spokeswoman that they had no safety concerns about the track.[73]

Minor changes were made to the track on 22 February 2010 after bobsleigh four-man teams from Latvia and Croatia rolled over in supplementary practice.[74] Following a meeting with 11 team captains, practice runs were postponed by the FIBT until later that day to adjust the shape of turn 11 so it would be easier for sleds to get through the rest of the track without crashing.[74] FIBT spokesman Don Krone also stated that it was common that turn profiles were changed when it was being used by other sliding disciplines such as luge and skeleton.[74]

After track alterations were done on 23 February 2010, the two fastest four-man practice times were done by Germany's Lange and the United States' Steven Holcomb.[75] Australia withdrew its four-man team on 23 February 2010 after two of its crew members suffered concussions from crashes sustained during track practice.[74] Australia's chef de mission Ian Chesterman stated that the decision was not taken lightly and was done on the side of safety.[74]

In the two-woman event, defending world champion Nicole Minichiello of Britain had her sled flip over after turn 12 during the third run, but both Minichiello and her brakeman Gillian Cooke walked away from the crash.[76] Minichiello and Cooke decided not to start the final run.[76] In the final run, Russia-2's sled crashed which kept them at their finishing position of 18th.[76] Meanwhile, the Germany-2 sled of Cathleen Martini and Romy Logsch was in fourth place after the third run, but was disqualified after Martini crashed in turn 13 of the final run, causing Logsch to be ejected from the sled.[76] Both Martini and Logsch walked away from the crash by themselves.[77] Before this incident, Martini had never crashed before in her career.[77] Canada's Kaillie Humphries and Heather Moyse won the event.[78]

Lange had the fastest practice times in the four-man event on the 24th with the final two practices taking place on the 25th.[79]

For the four-man event's first two runs on 26 February, defending world champion Holcomb recorded the fastest track times in both runs while defending Olympic champion Lange had the fastest start times.[80] Russia-2 driven by Alexandr Zubkov, the defending four-man silver medalist and bronze medalist in the two-man event at these Games, crashed out in the first run when one of his steering ropes broke.[80] Austria-1 and Slovakia-1 also crashed out in the first run, and neither sled started the second run with Russia-2.[80] Second run crashes involved USA-2, Great Britain-1, and Japan-1.[80] USA-2 did not start the third run.[81] There were no crashes in the final two runs of the event.[81] America's team of Holcomb, Steve Mesler, Curtis Tomasevicz, and Justin Olsen won the event.[81]

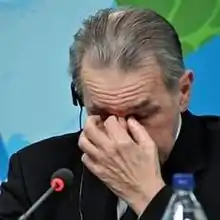

Overall safety concerns

Kumaritashvili's death raised concerns about athlete safety at the Winter Olympics.[82] As of 21 February 2010, there were 30 crashes in bobsleigh and luge at the Sliding Centre.[82] Debate was raised on tightening qualification standards in weeding out unqualified athletes, in requiring a large number of training runs, in slowing down the sliding tracks, or in combining the three.[82] Organizers of the 2014 Winter Olympics said that the Russian National Sliding Centre was designed to be 6 to 9 km/h (3.7 to 5.6 mph) slower than the Whistler Sliding Centre.[82] Sochi's Sliding Centre was to be monitored via 3-D computer graphics and simulation.[82] The IOC has improved safety standards over the years such as lowering obstacles for the equestrian three-day event, requiring protective head gear for boxing and ice hockey, and tightening qualification standards to preclude athletes not qualified for the event.[83] FIBT President Storey wanted to wait to review safety of bobsleigh, luge, and skeleton until after the 2010 Games, stating that track designers needed to find a balance between challenges and dangers on the track.[83] Track designer Gurgel told Sport Bild that perhaps track walls should be raised 40 to 50 cm (16 to 20 in) on future courses though a risk-proof course may not be possible.[82] According to VANOC, over 30,000 runs were made prior to the games with neither the FIBT nor the FIL issuing public danger warnings about the track.[82] IOC President Jacques Rogge stated that he "will do everything in my power that this should not happen again in the future".[82]

The FIL published their reports in regards to Kumaritashvili's death following the FIL Commissions Meeting in St. Leonhard, for both sport and technical commissions on 9–11 April 2010.[84] This report was prepared by Romstad and Claire DelNegro, FIL Vice-President Sport Artificial Track.[84] The 20-page report was released by the FIL to the IOC on 12 April 2010 and was released on FIL's website to the public on 19 April 2010.[16][85][86] Documents released in February 2011 showed that the speed of the course was a concern for several years before Kumaritashvili's death.[87]

Track technical details

Construction

This venue was constructed on a First Nations designated site. According to the Squamish, the area is referred to as a "Wild Spirit Place" or Kwekwayex Kwelh7aynexw while the Lil'oet call the area A7x7ulmecw or "Spirited Ground". It represents the beating of the Thunderbird's huge wings filled with thunder in the air.[88]

Originally budgeted for C$55 million, the track's actual costs were C$105 million (€68 million).[22] The track is made of 350 metric tons (340 long tons; 390 short tons) of reinforced concrete that was applied using pressurized spraying to reach a maximum thickness of 6 in (15 cm).[6][8][32] Additionally, the track contains 12 km (7.5 mi) of steel conduit, 600 awnings, and 700 lights. A total of 350 track footings were used to set the track on its proper foundation.[7] Forty percent of those footings were completed by July 2006.[7] There are over 100 km (62 mi) of ammonia refrigeration piping used to keep the track frozen.[7][32] Sloping and curves were contoured to within 1 to 3 mm (0.039 to 0.118 in) of the planned design course.[8] Ice thickness is 2 to 5 cm (0.79 to 1.97 in) that is maintained by hand.[32] There are 36 on-track video cameras and 42 "timing eyes" located at the Sliding Centre.[32] The track also includes a control tower and administration buildings.[7] There are two spectator overpasses (between turns 1 and 2, and turns 6 and 7) and three spectator underpasses (between turns 8 and 9, turns 11 and 12, and turns 15 and 16).[89] It seated 11,650 spectators during the 2010 Games.[6]

Sustainability

To promote sustainability, the site was selected directly adjacent to an already used part of a major ski area. It was also designed to minimize vegetation and the ecological footprint in the area. For energy efficiency, trees were retained to cast shade with weather protection and a shading system used to cover parts of the track. The track itself is painted white to maintain low temperatures while minimizing energy demand on the refrigeration system. Waste heat from the refrigeration plant is captured and reused to heat buildings on-site, and could provide other heat uses in the future. Any wood waste created from site clearing activities during venue construction was composted for reuse. Other on-site buildings also followed similar green building design principles.[90]

Awards

In 2008, the Sliding Centre received two British Columbia Ready-Mixed Concrete Association Awards for Excellence in Concrete Construction. The first award was for Public Works while the second one was for the Century Award.[91]

On 22 August 2006, VANOC targeted Leadership in Energy and Environmental Design Canada by applying for "silver" green building certification for the 708 m2 (7,620 sq ft) refrigeration plant building. The refrigeration plant received "gold" certification level on 2 February 2010.[92]

Characteristics

| Sport | Length | Turns | Vertical drop (start to finish) | Average grade (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bobsleigh and skeleton | 1,450 m (4,760 ft) | 16 | 152 m (499 ft) | 10.5 |

| Luge – men's singles | 1,374 m (4,508 ft) | 16 | Not listed | Not listed |

| Luge – women's singles and doubles | 1,193 m (3,914 ft) | 14 | Not listed | Not listed |

| Junior (bobsleigh, skeleton, luge) | 953 m (3,127 ft) | 11 | Not listed | Not listed |

| Turn | Name | Origin of the name | Ref |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Slingshot | For the slingshot effect of the turn after the start of the bobsleigh, skeleton, or men's single's luge run. | [93] |

| 2 | Fallaway | For the steep drop of the track after this curve. It has a 20% grade, the steepest part of the track. | [93] |

| 3 | Wedge | Where the doubles and women's single luge sleds coming from the start house "wedge" themselves onto the track. | [94] |

| 7 | Lueders Loop | After Canadian bobsledder Pierre Lueders, who crashed out at the curve during track certification in March 2008. | [22] |

| 9, 10 | Lynx | After the large population of Canada Lynx located in the British Columbia province. Also to the turn's being shaped like the head of the lynx if the track map is viewed from the air. | [22][94][95] |

| 11 | Shiver | After the turn "sending shivers down an athlete's spine" prior to entry into the next four corners of the track. | [22][94] |

| 12, 13, 14, 15 | Gold Rush Trail | Labyrinth of four curves without a straightaway. Named because a mistake on this part of the track could cost competitors a chance at a gold medal. It is also in reference to the British Columbia gold rushes that happened between 1850 and 1899.

Turn 13 of the Gold Rush Trail was christened "50/50" by American bobsledder Holcomb during the first day of four-man training in February 2009. 50% of the sleds crashed on Turn 13 on their runs that day. The next day, Holcomb posted the name on the wall of that turn, which the track manager approved. Holcomb's crew was also the first to go down the track that next day, successfully completing the run. The name stuck, being used in broadcast coverage of the Vancouver Olympics. Following Holcomb's death in 2017, turn 13 had his emblem (similar to Superman) embedded at the turn during the 2017-18 bobsleigh, luge, and skeleton World Cup season. |

[22][94] |

| 16. | Thunderbird | After the Thunderbird who is prevalent in much of Native culture in British Columbia. It represents the thunder in the air after a competitor finishes the track and is also its final curve. | [90][94] |

Turn names for 4–6 and 8 were not given.[22][94]

Track g-forces were expected to reach up to 5.02 for men's singles luge.[32] Maximum speed was reached at 147.9 km/h (91.9 mph) in four-man bobsleigh during the certification process.[32]

Track records

The luge track records shown were set at the men's singles start house and women's singles/men's doubles start houses during the World Cup competition in February 2009. After Kumaritashvili's death on 12 February 2010, the competition for men's singles was moved to the women's singles/men's doubles start house while the competition for women's singles/ men's doubles was moved to the junior start house. The fastest runs set during the 2010 Winter Olympics are not on this list until an issue between the Whistler 2010 Sports Legacies and the FIL is resolved.

| Event | Record | Athlete(s) | Date | Time (s) | Ref |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bobsleigh – two-man | Start | 6 February 2009 | 4.70 | [72] | |

| Bobsleigh – two-man | Track | 20 February 2010 21 February 2010 |

51.57 | [72] | |

| Bobsleigh – four-man | Start | 26 February 2010 | 4.70 | [81] | |

| Bobsleigh – four-man | Track | 25 November 2017 | 50.66 | [96] | |

| Bobsleigh – two-woman | Start | 23 February 2010 24 February 2010 |

5.11 | [78] | |

| Bobsleigh – two-woman | Track | 24 February 2010 | 52.85 | [78] | |

| Men's skeleton | Start | 18 February 2010 | 4.48 | [64] | |

| Men's skeleton | Track | 25 November 2017 | 51.99 | [64] | |

| Women's skeleton | Start | 18 February 2010 | 4.90 | [65] | |

| Women's skeleton | Track | 19 February 2010 | 53.68 | [65] | |

| Luge – men's singles | Start | 21 February 2009 | 3.541 | [97] | |

| Luge – men's singles | Track | 21 February 2009 | 46.808 | [97] | |

| Luge – women's singles | Start | 20 February 2009 | 7.183 | [98] | |

| Luge – women's singles | Track | 20 February 2009 | 48.992 | [98] | |

| Luge – men's doubles | Start | 20 February 2009 | 7.054 | [99] | |

| Luge – men's doubles | Track | 20 February 2009 | 48.608 | [99] |

References

- "Facts and Figures". Whistler Sliding Centre. Archived from the original on 4 October 2011. Retrieved 3 July 2008.

- "Past Olympic city post election results". Gamesbids.com. 20 June 2010. Archived from the original on 17 March 2011. Retrieved 20 June 2010.

- "VANOC selects designer for Whistler Sliding Centre". Vancouver Organizing Committee for the 2010 Olympic and Paralympic Winter Games (VANOC). 15 November 2004. Retrieved 11 February 2008.

- "Leistungsspektrum Planungphase" (in German). IBG-Gurgel. Archived from the original on 19 July 2011. Retrieved 1 April 2010.

- "Whistler Sliding Centre Environmental Screening Process" (PDF). VANOC. 8 June 2005. Retrieved 11 February 2008.

- "Preliminary site preparation begins on schedule at the Whistler Sliding Centre". VANOC. 7 June 2005. Retrieved 11 February 2008.

- "Construction Update: Whistler venues taking shape". VANOC. 25 July 2006. Retrieved 11 February 2008.

- "Pride in a job well done". VANOC. 14 December 2007. Retrieved 11 February 2008.

- "More than two years before Games begin, construction completed at all Whistler-based Vancouver 2010 competition venues". VANOC. 13 December 2007. Retrieved 11 February 2008.

- "Canadian bobsleigh hero takes first test runs at The Whistler Sliding Centre". VANOC. 21 December 2007. Retrieved 11 February 2008.

- "Leuders Takes First Run on 2010 Winter Olympic Track". FIBT. 21 December 2007. Retrieved 9 December 2009.

- "Team Canada not to compete in the final – Office in Whistler opened". International Luge Federation. 13 February 2008. Retrieved 13 February 2008.

- "Homologation at Whistler Sliding Center". FIL. 27 February 2008. Retrieved 4 March 2008.

- "Homologation Process Completed at 2010 Olympic Track". FIBT. 11 March 2008. Retrieved 11 March 2008.

- "The Whistler Sliding Centre homologation process complete". VANOC. 9 March 2008. Retrieved 11 March 2008.

- "Official Report to the International Olympic Committee on the accident of Georgia athlete Nodar Kumaritashvili at Whistler Sliding Center on February 12, 2010 during official luge training for the XXI. Winter Olympics Games" (PDF). FIL. 12 April 2010. Retrieved 19 April 2010.

- "2010 Olympic Winter Games already on the horizon". FIL. 23 September 2008. Retrieved 3 October 2008.

- "First crucial test for Olympic luge track in Whistler". FIL. 4 November 2008. Retrieved 21 November 2008.

- "World Champion Felix Loch injured". FIL. 20 November 2008. Retrieved 21 November 2008.

- "VANOC Board of Directors approves revised budget in principle; Jack Poole re-elected as chairman". VANOC. 9 December 2008. Retrieved 10 December 2008.

- "FIL President Fendt has speed limit in mind". FIL. 12 December 2008. Retrieved 13 December 2008.

- "153,98 km/h – new speed record at the "Whistler Sliding Center"". FIL. 23 February 2009. Retrieved 23 February 2009.

- "The Whistler Sliding Centre wraps up World Cup events. Sliding sport events charm sold-out crowds, yields track records, and produce top speeds". VANOC. 21 February 2009. Retrieved 24 February 2009.

- "Team Event in St. Moritz Cancelled". FIBT. 17 January 2009. Retrieved 18 January 2009.

- "Testing successfully complete at bobsleigh and skeleton sport event. Sold-out crowd cheers sliding athletes from around the world". VANOC. 7 February 2009. Retrieved 8 February 2009.

- "Lake Placid to Host 2013 World Championship". FIBT. 31 May 2009. Retrieved 20 June 2010.

- "Exactly four months before the opening ceremony on February 12, 2010". FIL. 12 October 2009. Retrieved 15 October 2009.

- "Hüfner: "Scrutinize ideal racing line and sled configuration"". FIL. 9 November 2009. Retrieved 12 November 2009.

- Kerby, Trey (18 February 2010). "'Nearly every athlete is scared to death' of the Olympic luge track". Yahoo! Sports. Retrieved 19 February 2010.

- "National Championships in Whistler on December 17, 2009". FIL. 9 December 2009. Retrieved 9 December 2009.

- "Official website". The Whistler Sliding Centre. Retrieved 3 July 2008.

- "The Whistler Sliding Centre and Whistler Olympic Park open to public tours". VANOC. 5 June 2008. Retrieved 6 June 2008.

- "VANOC Board of Directors receives business plan update, endorses updated plans to engage public in the 2010 Winter Games". VANOC. 21 May 2008. Retrieved 22 May 2008.

- "56th FIL Congress in Calgary". FIL. 29 April 2008. Retrieved 1 May 2008.

- "56th FIL Congress in Calgary". FIL. 28 June 2008. Retrieved 29 June 2008.

- "Recommendations for 2013 World Championships in Whistler". FIL. 8 April 2009. Retrieved 11 April 2009.

- "FIL Congress in Liberec". FIL. 20 June 2009. Retrieved 25 June 2009.

- "Whistler Legacy Society gets new identity". Resort Municipality of Whistler. 9 February 2009. Retrieved 5 April 2010.

- "About Us". Whistler 2010 Sports Legacies. Archived from the original on 7 June 2010. Retrieved 5 April 2010.

- "Luge Crash at the Olympics". The New York Times. New York, NY: Arthur O. Sulzberger, Jr. 12 February 2010. Retrieved 16 February 2010.

- Branch, John; Jonathan Abrams (12 February 2010). "Luge Athlete's Death Casts Pall Over Games". The New York Times. Retrieved 20 June 2010.

- Bryant, Howard; Bonnie D. Ford (13 February 2010). "Kumaritashvili killed in luge training". ESPN. Retrieved 20 June 2010.

- Bell, Terry (12 February 2010). "Georgia's minister of sport pleads for a full investigation after luger's death". Canwest News Service. Retrieved 12 February 2010.

- Wallechinsky, David; Loucky, Jaime (2009), "Luge (Toboggan): Men", The Complete Book of the Winter Olympics: 2010 Edition, London: Aurum Press Limited, p. 158

- "Luge: Luge start moved as officials defend Whistler Sliding track". VANOC. 13 February 2010. Retrieved 13 February 2010.

- "Joined Statement of IOC, FIL, and VANOC". FIL. 12 February 2010. Retrieved 13 February 2010.

- "Joint VANOC-FIL Statement on Men's Luge Competition". FIL. 13 February 2010. Retrieved 13 February 2010.

- Tom Pawlowski (16 September 2010), Coroner's Report into the Death of Kumaritashvili Nodar of Bakuriani, Georgia (PDF), Ministry of Public Safety and Solicitor General, British Columbia, archived from the original (PDF) on 19 October 2010, retrieved 19 October 2010

- "Joint VANOC – FIL Statement on Men's Luge Competition". VANOC. 12 February 2010. Retrieved 12 February 2010.

- Herman, Martyn (14 February 2010). "Women sliders now have kids race – German". Reuters. Retrieved 14 February 2010..

- Reich, Sharon (15 February 2010). "FIL considered cancelling competition". Reuters. Retrieved 16 February 2010.

- Herman, Martyn (16 February 2010). "Huefner's power nap leads to a golden dream". Reuters. Retrieved 17 February 2010.

- "A statement from Josef Fendt, President of the International Luge Federation". FIL. 18 February 2010. Retrieved 19 February 2010.

- Metreveli, Irakli (20 February 2010). "Track controversy hangs over Georgian lugers [sic] funeral". Oregon Herald. Portland, Oregon. Archived from the original on 20 July 2011. Retrieved 20 June 2010.

- de Sorin, Anghel (12 February 2010). "Violeta Strămăturaru – out!" (in Romanian). Jurnalul.ro. Retrieved 20 June 2010.

- "2010 Winter Olympics Luge women's singles official results". FIL. 16 February 2010. Retrieved 1 April 2010.

- Herman, Martyn (18 February 2010). "Clinical Lingers time it right once again". Reuters. Retrieved 20 June 2010.

- "Sports Review of the 2010 Winter Olympic Games in Vancouver". FIL. 19 February 2010. Retrieved 20 February 2010.

- "2010 Winter Olympics Luge men's singles official results". FIL. 14 February 2010. Retrieved 1 April 2010.

- "2010 Winter Olympics Luge doubles official results". FIL. 17 February 2010. Retrieved 1 April 2010.

- Herman, Martyn (15 February 2010). "Full fury of Whistler unleashed again". Reuters. Retrieved 20 June 2010.

- "Canadian Skeleton Team Tops Day Two Training". FIBT. 17 February 2010. Retrieved 17 February 2010.

- "Hollingsworth, Montgomery Solidify Favorite Status in Skeleton". FIBT. 18 February 2010. Retrieved 18 February 2010.

- "2010 Winter Olympics Skeleton men's official results" (PDF). FIBT. 19 February 2010. Archived from the original (PDF) on 8 January 2014. Retrieved 1 April 2010.

- "2010 Winter Olympics Skeleton women's official results" (PDF). FIBT. 19 February 2010. Archived from the original (PDF) on 20 September 2012. Retrieved 1 April 2010.

- "Lange Among Leaders in 2-Man Bob Training". FIBT. 18 February 2010. Retrieved 18 February 2010.

- "Rush, Lange, Florshuetz Top 2-Man Training". FIBT. 19 February 2010. Retrieved 19 February 2010.

- "Supplementary Bobsleigh Training Offered in Whistler". FIBT. 19 February 2010. Retrieved 19 February 2010.

- "Lange Takes Lead in Two-Man Bobsleigh". FIBT. 21 February 2010. Retrieved 21 February 2010.

- "Bobsleigh Schedule for Sunday Changed to 16:00". FIBT. 21 February 2010. Retrieved 21 February 2010.

- Withers, Tom (22 February 2010). "German driver Lange makes history with 4th gold". Comcast.net. Retrieved 9 August 2010.

- "2010 Bobsleigh two-man official results" (PDF). FIBT. 21 February 2010. Archived from the original (PDF) on 18 September 2012. Retrieved 1 April 2010.

- Leicester, John (21 February 2010). "Speed of Olympics bobsled track is fast becoming a debate among competitors". Cleveland.com. Retrieved 25 July 2010.

- Herman, Martyn (22 February 2010). "Whistler track tweaked after further spills". Reuters. Retrieved 20 June 2010.

- Herman, Martyn (23 February 2010). "Lange quickest in training as track mellows". Reuters. Retrieved 20 June 2010.

- "Humphries and Moyse Take Women's Bob Gold". FIBT. 25 February 2010. Retrieved 25 February 2010.

- Hendricks, Maggie (24 February 2010). "German bobsledding favorites in frightening crash". Yahoo! Sports. Retrieved 25 February 2010.

- "2010 Winter Olympics Bobsleigh two-woman official results" (PDF). FIBT. 24 February 2010. Archived from the original (PDF) on 20 September 2012. Retrieved 1 April 2010.

- "Lange Among Top 4-Man Pilots in Training". FIBT. 24 February 2010. Retrieved 25 February 2010.

- "Holcomb Takes First Day 4-Man Lead". FIBT. 27 February 2010. Retrieved 27 February 2010.

- "2010 Winter Olympics Bobsleigh four-man official results" (PDF). Fédération International de Bobsleigh et de Tobogganing (FIBT). 27 February 2010. Archived from the original (PDF) on 17 September 2012. Retrieved 28 February 2010.

- "IOC to act on luge death tragedy". Olympics-NOW.com. Associated Press. 21 February 2010. Archived from the original on 14 July 2011. Retrieved 9 August 2010.

- Withers, Tom (20 February 2010). "US bobsledder: Whistler track 'stupid fast'". Yahoo! Sports. Retrieved 25 July 2010.

- "FIL Final Report to be published after the Commissions meetings". FIL. 25 March 2010. Retrieved 27 March 2010.

- "Publication on Monday: FIL submit reports to IOC". FIL. 13 April 2010. Retrieved 14 April 2010.

- "FIL publishes Accident Report". FIL. 19 April 2010. Retrieved 19 April 2010.

- Associated Press, "Lugers' speed caused concern: e-mails", Japan Times, 9 February 2011, p. 15.

- "The Whistler Sliding Center official story" (PDF). The Whistler Sliding Centre. Archived from the original (PDF) on 20 March 2009. Retrieved 10 December 2009.

- "Street map leading to the Whistler Sliding Centre, including the track map itself". VANOC. Retrieved 17 December 2009.

- "Sustainability and legacy information on the site selection area for the Whistler Sliding Centre". VANOC. Retrieved 10 December 2009.

- "2008 BC Awards for Excellence in Concrete Construction, including the Whistler Sliding Centre" (PDF). British Columbia Ready-Mixed Concrete Association. Archived from the original (PDF) on 6 July 2011. Retrieved 10 December 2009.

- "The Whistler Sliding Centre Refrigeration Building". Canada Green Building Council. Retrieved 28 March 2010.

- Ogilive, Clare (18 February 2009). "Speedy sliding track gets a few nicknames". The Province. Vancouver, British Columbia, Canada: Canwest Publishing. Retrieved 20 June 2010.

- "Whistler Sliding Centre Facts". USA Today. McLean, Virginia: Gannett Company. 3 February 2010. Retrieved 7 February 2010.

- Hatler, David F.; Alison M. M. Beal (2003). "Furbearer management guidelines: Lynx (Lynx canadenis)" (PDF). Habitat Conservation Trust Fund. Retrieved 7 February 2010.

- "2017 IBSF World Cup Bobsleigh two-man official results". IBSF. 25 November 2017. Retrieved 25 November 2017.

- "Luge World Cup Whistler men's singles results". International Luge Federation (FIL). 21 February 2009. Retrieved 1 November 2009.

- "Luge World Cup Whistler women's singles results". FIL. 20 February 2009. Retrieved 1 November 2009.

- "Luge World Cup Whistler men's doubles results". FIL. 20 February 2009. Retrieved 1 November 2009.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Whistler Sliding Centre. |

- FIBT track profile – Men's singles luge join the track prior to turn one while women's singles/ men's doubles luge join prior to turn three.

- Official website

- Official Report to the International Olympic Committee on the accident of Georgian athlete Nodar Kumaritashvili

- Vancouver2010.com profile