Willamette Falls Locks

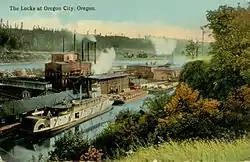

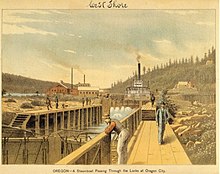

The Willamette Falls Locks are a lock system on the Willamette River in the U.S. state of Oregon. Opened in 1873 and closed since 2011, they allowed boat traffic on the Willamette to navigate beyond Willamette Falls and the T.W. Sullivan Dam. Since their closure in 2011 the locks are classified to be in a "non-operational status" and are expected to remain permanently closed.

| Willamette Falls Locks | |

|---|---|

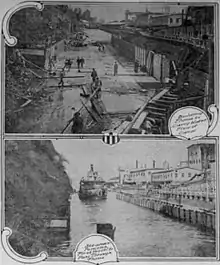

.jpg.webp) (upper) Willamette Falls Locks 1990; (lower) circa 1915, Grahamona in transit. | |

| Specifications | |

| Maximum boat beam | 77.5 m (254 ft 3 in) |

| Locks | four |

| History | |

| Original owner | Willamette Falls Canal & Locks Co. |

| Principal engineer | Isaac W. Smith |

| Date of act | October 26, 1868 |

| Construction began | January 1, 1871 |

| Date completed | 1873 |

| Date closed | November 17, 2011 |

Willamette Falls Locks | |

Steamboat and barge traffic in the lock, circa 1915 | |

| |

| Location | West Linn, Oregon, US |

|---|---|

| Coordinates | 45°21′19″N 122°37′3″W |

| Built | 1873 |

| NRHP reference No. | 74001680 |

| Added to NRHP | 1974 |

Located in the Portland metropolitan area, the four inter-connected locks are 25 miles upriver from the Columbia River at West Linn, just across the Willamette River from Oregon City. The locks were operated by the United States Army Corps of Engineers and served primarily pleasure boats. Passage through the locks was free for both commercial and recreational vessels. The locks were added to the National Register of Historic Places in 1974.

The locks comprise seven gates in four chambers which lift up to 50 feet (15 m) elevation change (depending on tides and river flow) with a usable width of 37 feet (11 m). The system is 3,565 feet (1,087 m) long, and can accommodate vessels up to 75 feet (23 m) long. Each of the four concrete constructed chambers are 210 by 40 feet (64 by 12 m).[1]

Preparations for construction

The canal and locks were built from 1870 to 1872.[2] Much legal, organizational, and financial work had to be done before construction could begin. The Willamette Falls Canal and Locks Company (later renamed Portland General Electric) was formed in 1868 to build a navigation route around the falls.[1][3] This company was incorporated by a special act of the legislature.[4] At that time, all transshipment of freight across the Willamette Falls was controlled by the People's Transportation Company, often referred to as the P.T. Co. Ownership of this key point in the river gave the P.T. Co. the ability to quell all competition for shipping on the Willamette River.[4] The canal and locks were built in part to break the market domination of the P.T. Co. over riverine transport on the Willamette.

Incorporation of canal and locks company

The Wallamet Falls Canal and Locks Company, with authorized capital of $300,000, was incorporated on September 14, 1868 by N. Haun, Samuel L. Stephens, of Clackamas County, and experienced steamboat captain Ephraim W. Baughman (1835–1921)[5][6] to "locate and construct a canal and suitable boat locks at the falls of the Willamette River, on the west side of said falls".[7][8]

Government subsidy

On October 26, 1868, the Oregon legislature approved a law entitled "an Act to appropriate funds for the construction of a Steamboat Canal at Wallamet Falls."[9][8] The law stated it was "of great importance to the people of Oregon" that a canal and locks be built on the west side of Willamette Falls and that the rates for carriage of freight on the Willamette River be reduced by this construction", and so it granted the company a subsidy of $150,000, to be paid in six annual installments of $25,000, starting on the date the canal and looks were completed, with the money to come from lands donated to the state of Oregon by the United States for internal improvement.[9]

As condition precedent to receipt of the funds, by January 1, 1871, the company was to expend at least $100,000 and complete construction, on the west side of the falls, a functioning canal, "constructed chiefly of cut stone, cement and iron, and otherwise built in a durable and permanent manner" with locks not less than 160 ft (49 m) long and 400 ft (122 m) wide."[9] Upon completion, a commission appointed by the governor was to inspect the works to determine if they were constructed in compliance with the law, and if not, no subsidy would be paid.

Toll authority

The company could charge tolls, for the first ten years after completion, of no more than seventy-five cents per ton for all freight, and twenty cents per passenger. After ten years, maximum tolls would fall to fifty cents per ton of freight and ten cents per passenger. Twenty years after completion, the State of Oregon would have an option to buy canal at its actual value. The company was also required to pay 10% of the net profit from tolls to the state for the first ten years, and 5% thereafter.[9]

Investors sought

In early 1869, the company sought investors by publishing a prospectus,[10] which among other claims, predicted that 60,000 tons of freight and 20,000 passengers would pass through the canal and locks every year, which turned out to be an overstatement by a factor of several hundred percent.[11] The company was also reported to have sent an agent east to negotiate financing.[12]

Condemnation actions

In March 1869, the company's attorney, Septimus Huelat, brought condemnation actions in Clackamas County Circuit Court, to acquire, in Linn City, a strip of land about 2,014 feet (614 m) long and 60 feet (18 m) wide[13] By 1869 Linn City was a settlement in name only, as the actual town, located on the west side of the river just below the falls, had been washed away by a flood in December 1861.[14][8]

Legislative action

The deadline set by the legislature in the 1868 legislation proved to be impossible to meet.[8][11] The subsidy was too small to attract investors.[11] New legislation was approved in 1870.[8][15] The 1870 law was substantially similar to the 1868 legislation, except that it increased the subsidy to $200,000, in the form of bonds payable in gold issued by the state of Oregon, to be issued upon posting of a surety bond in the amount of $300,000.[8] The state-issued bonds were to fall due on January 1, 1881.[16] Maximum tolls chargeable were in all circumstances to fifty cents per ton of freight and ten cents per passenger. The deadline for completion was rolled back to January 1, 1873.[8][4]

Further corporate action

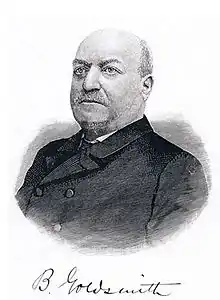

At the December 1870 annual meeting, Bernard Goldsmith and Joseph Teal, both of Portland, Orlando Humason and Jason K. Kelly, both of The Dalles, John F. Miller, of Salem, and David P. Thompson, of Oregon City were elected directors, who then on December 8, 1871, appointed company officers: Bernard Goldsmith, president; John F. Miller, vice-president; Joseph Teal, treasurer; and Septimus Huelat, from Oregon City, attorney and secretary.[17][3] On February 3, 1871, supplemental articles of incorporation were filed, giving the company broadly expanded authority to collect tolls, deal in water rights and real property, and own and operate industries and steamboats.[8]

The $200,000 in state-issued bonds were augmented by an additional $200,000 in bonds issued by the company.[18] Both bond issues were sold at a discount, the state bonds at 80% and the private bonds at 77.5%, and the proceeds, of $315,500, were used to build the locks and canal.[18]

Design

The initial design, in January 1869, was reported to have been for a canal was 2,500 feet long, and 40 feet wide, with three locks about 200 feet long.[19] However, bids were solicited in early 1871, based on plans and specifications of Calvin Brown, which called for four locks, each 160 feet long, with the canal about 2,900 long, and a wooden wall the whole length of the canal, with the locks themselves built of masonry.[20]

Isaac W. Smith took over as chief engineer in February 1871, before construction began.[20] Smith recommended that the wooden wall be replaced with one built of stone, that the length of all locks be increased to 210 feet, and that a fifth lock, known as the "guard" lock, 1200 feet along the canal from the fourth lock. The contracts were let out on this basis.[20]

However, after carrying out only a small part of the work on the new basis, the contractors were unable to complete it. In December 1871, Smith reported to the company's board of directors that he had incorrectly calculated the quantity and cost of the rock that could be obtained near the work, and that stone walls could not be completed by the project deadline of January 1, 1873.[20]

By May 31, 1872, Smith had switched back to a timber wall, heavily bolted with iron and weighed down with stone.[20] The switch was claimed to have saved from $75,000 to $100,000 from the construction costs, but it was criticized at the time as not being in compliance with the standards established by the state for the construction of the canal.[21]

Cost

Various statements have been published as to the costs of the works. In 1893, a committee of the state legislature, in studying whether the state should purchase the locks, found that between $300,000 and $325 had been expended on construction.[18] A study conducted in 1899 by the Corps of Engineers found an original incorporator of the company who stated that the total cost of the lock construction was $339,000, of which $35,000 was used to acquire the right of way, and a further $20,000 was used for "political extras", leaving the actual cost of construction as $284,000.[18]

Construction

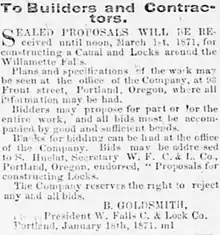

Bids

On January 18, the company, from its headquarters at 93 Front Street, in Portland, called for sealed bids from contractors, with bidding to close at noon on March 1, 1871.[22] Capt. Isaac W. Smith was the chief superintendent. E.G. Tilton was the chief Engineer; Tilton's assistant was J.A. Lessourd, who superintended the construction of the gates and the iron and wood work. Major King was the secretary for the project.[4] A.H. Jordas, an engineer and architect from San Francisco, became one of the contractors and went on to supervise the work.[23]

The targeted completion date was December 1, 1872. The contractors were under heavy bond to finish the work by that time. Monthly payments to the contractors were based on the estimates of the supervising engineer, who lived at the works. The company held back 20% of the contract price as security for completion.[23] Up to October 1872, the total cost of the work was estimated to have been $450,000, with about $50,000 more needed to be expended before completion.[4]

Blasting

Blasting holes in the rock were cut by then-new steam-driven diamond-tipped drills manufactured by Severance & Holt, and mounted on small cars allowing them to be moved about the work as needed.[23] Rather than reduce the rock to powder, as on previous designs, these drills cut a ring into the rock about 2 inches in diameter, with the remaining portion of the rock, called the core, passing out through a water-cooled iron tube.[23] Twenty to thirty holes were drilled on a daily basis. Each drill could bore five to seven feet per hour. Blasting had to be done carefully so as not to make the spoil too small, as the broken rock was intended to be used for the stonework.[23]

A temporary dam was projected to be needed across the upper end of the works. As of September 1871, two steam derricks and two blacksmith's shops were employed on the works.[23] Gates were to be set in the eastern wall of the canal to allow use of the river's water by industries to be located along the canal.[23]

Dissipation of funds

In November 1871, one of the contractors, a Mr. Jordan, disappeared, leaving unpaid debts to various creditors of about $28,000 or more, as well as unpaid wages of $6,000.[24] The company agreed to pay the wage claims. Isaac W. Smith took over Jordan's place, with the objective to speed construction as fast as weather permitted, and put an additional workforce in the spring if 1872 to meet the company's deadline as set by the state.[24]

Workforce

Between 300 and 500 men worked on the project.[4] About 100 men worked at night for most of the time.[4] As of September 1871, the contractor was reported to have difficulty obtaining laborers and stonemasons, with only about 100 then being employed, with openings for 100 to 150 more. Reportedly that the "site of the works is healthy" and laborers would be paid wages equivalent to $2 per day in coin, with stonemasons receiving more.[23]

Masons and stone-cutters were paid from $5 to $6 per day, carpenters from $3 to $3.50 per day, and laborers received $2.50 per day. The monthly payroll was $50,000.[4] On July 27, 1872, the Morning Oregonian reported that "sixty Chinamen are now employed at the locks at Linn City."[25] The successful completion of the project was reported to have been "secured by treating the men kindly and considerately and paying them liberally and promptly."[4] Additionally, it was reported that "the full pay of every man was never a minute behind time."[4]

Excavation

Excavation consisted of 48,603 cubic yards (37,160 m3) of rock, 1,334 cubic yards (1,020 m3) of loose rock, and 1,659 cubic yards (1,268 m3) of earth. Masonry installed comprised 900 cubic yards (688 m3) of first class work, 4,423 cubic yards (3,382 m3) of second class, and 700 cubic yards (535 m3) of third class. There was a gulch north (downstream) of the guard lock, which was filled in with 20,000 cubic yards (15,000 m3) cubic yards of stone[26] or 40,000 tons.[20]

Exclusive of the foundation walls and fenders, the project consisted of 1,138 lineal feet (347 m) of masonry, 1,042 ft (318 m) of timber walls above the guard lock, and 1,192 ft (363 m) of timber walls below the guard lock.[26]

Explosives used during construction included 18,000 pounds of giant powder and 10,000 pounds of black powder.[4] Materials used in construction were 5,123 pounds of cement, 1,326,000 board feet of lumber, 180,700 pounds of iron for the gates, 71,000 pounds of iron for bolts for the canal walks, fenders and other components, not including iron used in machinery, derricks and other equipment, but only iron placed in the works.[26]

Completion and opening ceremony

The locks were reported to be ready to pass vessels through on December 16, 1872, however the company intended to test the locks with a scow before letting any steamboats transit.[27] A steamer was expected to be able to use the locks on December 25, 1872, however this proved impossible, because some of the gates were not working properly, and a few more days work would be necessary.[28]

Governor La Fayette Grover appointed three commissioners, former governor John Whiteaker, George R. Helm, and Lloyd Brook to examine the locks and accept them on behalf of the state if they were constructed in accordance with the law.[29] The commissioners inspected the locks on Saturday, December 28, 1872.[29]

Maria Wilkins, a steamship, was the first vessel to use the locks.[1]

The locks were first placed in use on Wednesday, January 1, 1873.[30] At 12:17 the small steamer Maria Watkins entered the first lock. Watkins was late, having been expected to arrive at 11:00 a.m. A large crowd of spectators cheered from alongside the walls of the lock as the steamer entered. The boat responded to the cheers with three blasts from the steam whistle.[30]

Each lock raised the vessel ten feet. After Watkins had transited the locks into the upper river, Governor Grover made some congratulatory remarks to the president of the locks company. This was met with three cheers, for the company's president, Bernard "Ben" Goldsmith, Col. Teal, Capt. Isaac W. Smith, and the governor. Watkins was carrying a number of dignitaries, including Gov. La Fayette Grover (1823–1911), Mayor of Portland Philip Wasserman, several newspaper editors, steamboat captain Joseph Kellogg, the locks commissioners, and other invited guests. There was only one woman on board. It took one hour forty-five minutes to pass Watkins through the locks. Returning down river took about an hour for the boat to transit the works. It was expected that the transit time could be cut down to one-half hour.[30]

Grover's support of the locks company was criticized a few years later, in 1878, in the Willamette Farmer (reprinted in the Oregon City Enterprise), which described the then-former governor as a "senile nincompoop" a "lick spittle and fawning sycophant" and the chief of the "minions and tools" of the Oregon Steam Navigation Company, whose principals had, by 1878, acquired control of the locks.[31]

Dimensions in 1873

_hi-res.jpeg.webp)

Upon completion, the total length of the canal and locks was 3,600 ft (1,097 m), consisting of, from north (downstream) to south (upstream):

- the approach to the first, or north lock, 200 ft (61 m) and 50 ft (15 m) feet wide.[30]

- four lift locks, each 210 ft (64 m) long and 40 ft (12 m) wide;

- the canal south of the lift locks, 1,273 ft (388 m) long and 60 ft (18 m) to 100 ft (30 m) wide;

- a guard lock 210 ft (64 m) long and 40 ft (12 m) wide;

- a canal and basin, 1,077 ft (328 m) and from 80 ft (24 m) to 250 ft (76 m).[26]

Lock design

The lift locks were of a type known as "combined" locks, with the lower gate of one lock functioning as the upper gate of the lock next below.[26] The lifting lock walls stood 19 ft (5.8 m) above the lock floors, and were 5 ft (1.5 m) at the top, with a batter of 3 inches per foot (25 cm/m). All walls had their foundation on solid rock. The guard lock wall was 16 ft (4.9 m) high above the guard lock floor, but otherwise was similar to the walls at the lifting locks.[26]

The lifting locks were referred to by number, with lock 1, the furthest downstream, being both the northernmost and the lowest. The first and second locks were cut entirely out of solid rock except for the areas around the gates, where masonry was set in for the hollow quoins and supports for the gates.[26] Each hollow quoin weighed 2 tons.[4]

Wooden fenders were bolted to the lock sides to prevent harm to vessels coming into contact with the natural rock that formed the sides of the first and second locks.[26] The third lock likewise was cut into solid rock, but with walls above the surface. Wooden fenders, backed by three-inch timber, were tied into the rock with bolts. The fourth lock was almost entirely above the surface, with masonry walls on both sides.[26]

Each of the four lifting locks had a lift of 10 ft (3.0 m).[30] The total fall, from low water above the works, to low water below, was 40 feet.[30] The lower end of the canal had been cut 40 feet deep through solid basalt.[30]

About 700 ft (213 m) of the west wall was built of timber on top of a stone wall resting on bedrock. The stone wall was 8 ft (2.4 m) at the top, 3 ft (0.9 m) to 15 ft (4.6 m) high, with a batter of 3 inches per foot (25 cm/m). The rest of the west wall was hewn out of the natural rock.[26]

According to engineer Smith's 1873 report, the guard lock was left open when the water in the canal was less than 3 ft (0.9 m).[26] Otherwise, boats would have to lock through the guard lock.[26]

The guard lock was intended to prevent foods from flowing over the lower walls of the canal. In ordinary water conditions the guard lock would be left open, so as not to unnecessarily delay boats making the transit.[30] Upstream (south) from the guard lock, the east side wall was timber-built, with bents 5 ft (1.5 m) apart. Each bent was bolted to the bedrock by three iron rods extending the full height of the cross braces on the bent. The entire timber wall was filled with stone.[26]

Gate design

The gates were based on designs used in locks on the Monongahela River. Each swung on suspension rods mounted in iron brackets tied into masonry. The gates did not rest on rollers or tramways, and were easily worked by one man. Each gate had eight wickets, located near the bottom of the gate, with each wicket measuring 4 ft (1.2 m) by 2 ft (0.6 m).[26][4] The locks were flooded and drained by opening and closing the wickets, through the use of connecting rods.[4] Two men were required to work each gate.[4] There were two culverts under each gate sill to carry off mud and gravel which might otherwise impede the opening of the gates.[26] Each lock gate was 22 ft (7 m) long and 20 ft (6 m) high. Buttresses 16 ft (4.9 m) think reinforced the walls carrying the gates. The gates were opened and closed with cranks.[4]

The stone used for the masonry was local basalt, except for the rock used for the hollow quoins, which was a some different basaltic type, but drawn from a quarry on the Clackamas River owned by someone named Baker. The masonry was set with hydraulic cement with no lime intermixture.[26] The masonry walls were constructed of blocks of basalt, each weighing 1 to 2 tons.[30]

On completion, the maximum water depth in the lock was 3 ft (0.9 m).[26] A newspaper published at the time stated that the normal water depth in the river at the head of the canal was seven feet, and four and a half feet during low water seasons. This was sufficient to allow river boats to safety pass.[4]

Boats could transit the locks with up to 15 ft (4.6 m) of water on the upper guard lock gates. The guard lock was designed to allow a rail to be installed which would allow vessel transit with 17.5 ft (5.3 m) of water. However, on the few occasions every year when the river rose any higher, navigation could not be safely made, and the guard lock could not be opened.[26]

Operations 1873–1915

The masonry work was expected to last indefinitely, while the timber work was expected to be good for eight to ten years. Additional construction work still needed to be done for the first four or five months after the locks opened.

Afterwards, it was expected that the annual costs of repairs would not exceed $600. Staffing requirements were estimated to be one lock superintendent, at $125 per month, and two lock-tenders, at $50 each per month.[26] Some proponents of the canal and locks believed that their existence had a "regulating" effect upon railroad freight rates, by competing with the railroads for the shipper's business.[8][18]

New locks company formed

On December 28, 1875, William Strong, W.H. Effinger, and Frank T. Dodge incorporated the Willamette Transportation and Locks Company, capitalized at $1,000,000, in shares of $100 each, with generally the same corporate purposes as the Willamette Falls Canal and Lock Company.[8][32] On March 8, 1876, by a deed recorded in Clackamas County Willamette Falls Canal and Lock Company sold all its property, including the canal and locks, to Willamette Transportation and Locks Company for $500,000.[8][33]

On January 8, 1877, four prominent businessmen, John C. Ainsworth, Simeon G. Reed, Robert R. Thompson, and Bernard Goldsmith, filed supplemental articles of incorporation which increased the powers of Willamette Transportation and Locks Co.[8] As of May 5, 1877, Simeon G. Reed was the vice-president of the new corporation, which in addition to owning the locks, owned and operated steamboats on the Willamette river.[34] Ainsworth, Reed, and Thompson were closely associated with the powerful Oregon Steam Navigation Company (O.S.N.) An 1895 source considered the 1876 transaction to be a sale to the O.S.N.[5]

As of 1880, Willamette Transportation and Locks Co. was controlled by the Oregon Railway and Navigation Company (O.R.&N)[2]

Locks commission and toll collections

Oregon laws passed in 1876 and 1882 established a canal commission, composed of the governor, secretary of state, and the state treasurer, with the authority to visit the works and bring legal action to compel keeping and maintenance of the canal.[2] The consent of the canal commission was necessary for any repairs or improvements except in emergencies. Vessels using the canal were required report of freight tonnage and passengers carried.[2] The locks company was also required report quarterly to the canal commission.[2]

The first lock tender on duty was John "Jack" Chambers (1841–1929).[35] Chambers had been in charge of the heavy rock work during the construction of the canal and locks.[35] He was to serve on the locks for fifty years and became known to every steamboat captain that operated on the Willamette River.[35] Initial tolls for use of the locks were set at the legal maximum of fifty cents per ton of freight and 10 cents for every passenger.[4]

Despite the legal requirement to send the state 10% of the net toll proceedings, by 1893 only a single payment had been made, of $435 for the year 1873.[8] The justification for sending no other payments was that after that time there had been no net proceeds arising from the collection of tolls.[8]

On November 23, 1905, the state of Oregon, represented by attorney general A.M. Crawford, and district attorney John Manning, brought suit in the Oregon circuit court against the Portland General Electric Company to recover 10 percent of the tolls collected from the operation of the locks since 1873.[36]

In 1907, the toll collector at the locks was the local station agent of the O.R.&N (Southern Pacific) at Oregon City.[2] One-half of the agent's salary was paid by the O.R.&N and the other half was paid by Portland General Electric.[2]

In 1906, an Open River Association was formed at Albany, Oregon which argued for the acquisition by the public of the Willamette Falls Locks.[37] The Open River Association and its sympathizers favored free tolls after the government obtained the locks.[37]

On November 17, 1906, Judge Arthur L. Frazer (1860–1907), of the Multnomah County Circuit Court, ruled that the law requiring sharing of the net tolls with the state only applied to the Willamette Falls and Locks Company, and not to any successor in interprets, because the law referred to the Willamette Falls and Locks Company by name and did not include any successors or assigns, nor did the law make the state's share a specific charge upon the locks themselves.[38]

Financing, water rights, and corporation reorganizations

On January 1, 1887, Willamette Transportation and Locks Co. issued mortgage bonds in the amount of $420,000 to New York businessman and O.R.&N president Elijah Smith These bonds acted as a lien upon the canal and locks and were still outstanding in 1893.[8][39] In 1889, the company granted two industrial firms, Willamette Pulp and Paper Co, and Crown Paper Co. building sites along the canal and rights to withdraw water from the canal for industrial purposes.[2] To permit this without hindering navigation, an additional flume was built to fill the canal.[2]

On August 8, 1892, P.F. Morey, Frederick V. Holman, and Charles H. Caufield incorporated the Portland General Electric Company with a capitalization of $4,250,000. Among the purposes of the new company were the owning and operating of the Willamette falls canal and locks, as well as use of the water power of the falls for any lawful purpose. Charles H. Caufield, secretary of Portland General Electric, was formerly secretary of the Willamette Transportation and Locks Company.[2] On August 24, 1892, for nominal consideration, the Willamette Falls and Locks Company sold all its real property, including the canal and locks, to Portland General Electric.[8]

Oregon permitted the state to buy the locks and canal in 1893, twenty years after completion, but this option was never exercised.[18] Average toll receipts for the six years of 1887 through 1892 were approximately $15,750 annually. With the locks and canal estimated to have cost a total of $450,000, this would have a return, after deducting $2,700 for labor and $1,000 for repairs, which would have been a return of less than 2.75%.[2]

As of February 1908, the stock of the Portland General Electric company was owned by the Portland Railway, Light and Power Company.[2]

Flood damage 1890

The flood of 1890 seriously damaged the locks. The canal was flooded with debris.[35] Two lock gates were destroyed, as was the home of lock tender Jack Chambers.[35] Additional work was scheduled to be done in 1893, which was anticipated to cost between $135,000 and $150,000.[8]

The projected work consisted of widening 1,300 feet of the canal to 80 feet, and replacing a decaying and leaking portion of the timber-built wall with a masonry structure.[8] The widened canal would permit a faster transit of steamboats through the locks by allowing them to pass each other in the canal, and would permit a greater accumulation of water for industrial and navigation use.[8]

Additionally, at a cost of $16,000, the lower lock was to be deepened to allow safe passage of the larger steamboats when the river was at a low water state.[8]

Federal acquisition

On March 3, 1899, the locks were examined by a board of United States Engineers to report on whether the locks should be acquired by the United States Government.[18] By 1899, the wooden lock gates were rotten and leaking badly.[18] They had been replaced only once since 1873.[18] Nearly all the timber work would soon require replacement.[18] Woodwork in the region, if exposed to weather, required replacement about every eight to nine years, and in wet areas replacement was required even earlier.[18]

Study by Corps of Engineers

The total cost, in 1899, of work necessary to restore the locks to the original operating condition of 1873 was calculated to be about $38,800.[18] The 1899 replacement value of the entire project was calculated to be $314,300.[18] Using another method, including data from the net profits of the works, and including the anticipated costs of necessary replacement work, the Corps of Engineers estimated the value of the canal and locks, in 1899, as $421,000.[18]

The 1899 report recommended acquisition provided the locks could be purchased at a reasonable price.[18] (By this time the mortgage bonds issued to Elijah Smith had been paid off.[18]) However, the price asked by the owners, in 1899, was $1,200,000, which the government regarded as too high.[18] By 1899 the works were in poor repair and few improvements had been made.[18] So much water in the canal was diverted for manufacturing purposes that it seriously interfered with use of the locks for navigation.[18]

In the years 1882 through 1899 (half year), there were 12,863.5 lockages, carrying 234,451.5 passengers, and 504,145.04 tons of freight.[18] In the five years from 1894 through 1898, net profit for the locks ranged from a low of $21,210.13 in 1896 to a high of $28,503.10 in 1898.[18]

Steps towards acquisition

In June 1902, Congress passed a Rivers and Harbors act which authorized a study of whether the canal and locks should be acquired by the U.S. government.[40] In the previous year, Portland General Electric, had earned about $35,000 from the tolls on the locks and canal.[40] On November 21, 1902, a board of officers of the Corps of Engineers, consisting of Maj. John Millis, of Seattle, Capt. W/C Langfitt of Portland, and Lt. R.P. Johnson, of San Francisco, made a preliminary inspection of the locks.[41]

The major issue associated with the proposed purchase was the question of water rights.[41] The industries on the west bank of the river below the falls received all their power from water drawn from the navigation canal.[41] They used so much water that when the river level was low, it was impossible to conduct industrial operations and navigation at the same time.[41] The U.S. government was only willing to acquire the works if there would be sufficient water for navigation.[41] Another difficult point was that in 1902, the owner of the canal and locks, Portland General Electric, was continuing to ask the same sales price, $1,200,000, which the government had found too high in 1899.[41]

Portland General Electric argued that since it owned both sides of the Willamette River at the falls, it controlled all the rights to the use of the water flowing over the falls from bank to bank.[42] Consideration was then being given to the possibility of constructing a new canal on the east side of the falls rather than purchasing the existing canal on the west side.[42]

The company's position in response was that the government would have to condemn and pay for the water rights on any newly-constructed canal.[42] Oregon's U.S. Attorney John Hall was reported however to have turned in an opinion to the Attorney General that the government had the legal authority to build new locks, provided they were located below the ordinary high-water mark of the river.[42]

In 1907, the Oregon state legislature passed a bill appropriating $300,000 to be paid to the federal government to help purchase the Willamette Canal and Locks.[43] However, in 1908, Judge Frazer's decision was reversed following an appeal to the Oregon Supreme Court.* Oregon v. Portland General Electric, 52 Or. 502 (Sup.Ct. November 17, 1908).

On May 31, 1909, while replacing a lock gate, three men were injured when the false work supporting the old gate collapsed, and the gate fell, causing one man to sustain a broken leg, another was badly bruised, and a third man had lacerations on his legs.[44]

In 1911, the canal and locks were valued at $300,000 for property tax purposes, and assessed a tax of $5,587.50 against them, which was paid, late, by the owner of the works, the Portland Railway, Light & Power Co.[45]

Acquisition complete

In 1912, the War Department approved purchase of the locks from Portland Railway, Light & Power Company.[46] The purchase price was to be $375,000.[1][47] The transaction did not finally close until 1915.

The reason for the delay was the need to establish the vendor's title to the property, as well as to work out the details of the various conditions that the vendor wished to attach to the sale.[46] The title problems stem from the fact that the town of Linn City, which had been on the west side of the false, had been washed away by a flood in 1862, apparently along with all of its records.[48] While the owners and operators of the locks appeared to be able to claim title by adverse possession, this would not be considered sufficient by the U.S. government, which required proof of the plat map of the town of Linn City.[48]

By August 1912, a search was underway for a map of Linn City.[49] An official of the Corps of Engineers had heard from one old resident of Linn City that a map had survived the flood, but this map could not be found. The official intended to consult with George H. Himes, of the Oregon Historical Society to learn more about Linn City.[49]

Before the transfer to the U.S. government some mills near the locks drew their water directly from the upper lock level.[46] This created currents which impeded navigation through the lock. The government was unwilling to permit this to continue under its ownership, so, as part of the conditions of the sale, the United States would be required to build a wall in the navigation canal which would have the effect of creating a separate water source, with an opening well above the falls, for the canal side industries.

In April 1915 the cost of this wall, estimated to be between $125,000 and $150,000, would be the largest single item of work then planned for the locks and canal. Other work that the government intended to carry out included repair of the lock gates and deepening the approaches to the locks. The lower sill of the downstream lock was to be lowered, and a new pair of gates was to be constructed.[46]

Reconstruction 1916–1917

The reconstruction of the canal and locks was supervised by Major H.C. Jewett, of the Corps of Engineers, and E.B. Thomson, assistant engineer in the Second District.[50] Construction on the wall began in April 1916.[51] By September 1916, about 1000 feet of the wall to divide the canal and locks from the industrial flume had been built, using cofferdams. About 200 feet of wall downstream from the guard lock were still left to be completed. To permit river traffic to continue while reconstruction was underway, the Army Corps of Engineers built a wooden flume as a temporary canal.[50] A cofferdam would have been too costly to employ because of the depth of the water.[50]

The flume was to be 42 feet wide with a depth of 6 feet.[50] The inside of the flume would be sealed by spreading oil-treated canvas tightly over the planking.[50] The entire structure would be heavily braced to support the weight of the water and passing riverboats.[50] Construction of the flume would leave the bottom and both sides of the canal dry to permit the pouring of concrete.[50]

The wall was complete on September 1, 1917.[51] It was 1280 feet long, running from the guard lock to lock No. 4. At points the wall was more 50 feet high. The estimated cost of construction of the wall was $150,000, but it was reported to have been completed for considerably less.[51]

Congress had allocated $80,000 to improve the lower locks, by deepening them, installing concrete foundations under the lock gates, and other work.[51] However, upon completion of the canal wall, on September 1, 1917, shippers were opposed to the work being carried out at that time, because it would interfere with navigation. They wanted the work postponed until the summer of 1918 so that the harvest of 1917 could be moved downriver. The local Corps of Engineers wanted the work to continue interrupted, because a workforce had been assembled and Congress might reallocate the funds due to the war.[51]

Recent repairs and closure

With no funding available to perform needed inspections and repairs, the locks were closed in January 2008.[52][53] In April 2009, as part of the federal government's economic stimulus plan, $1.8 million was allocated to repair and inspect the locks, with an additional $900,000 allocated in October 2009 for additional repairs and operational costs.[54] The locks reopened in January 2010 with the Willamette Queen the first vessel to pass.[55] The locks were open through the summer of 2010, and then due to a lack of federal funding for operations, were not scheduled to reopen for 2011.[56]

In December 2011, the locks were again closed, this time owing to the excessive corrosion of the locks' gate anchors. The further deterioration of the locks resulted in the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers reclassifying the locks as being in a "non-operational status," out of concern that any further operation of the locks could lead to a failure of the locks, posing a safety risk to the public. The locks are expected to remain permanently closed, as the lack of traffic through the locks makes funding for any repairs a low priority.[57] However, some interest groups are urging the Army Corps of Engineers to reopen the locks, at least seasonally, and the Clackamas County Board of Commissioners added its support to that effort in December 2014.[58]

Placed on National Register

The locks were added to the National Register of Historic Places in 1974.

Notes

- Corning, Howard M. (1956). Dictionary of Oregon History. Binford & Mort.

- United States Congress (February 26, 1908). "Appendix: Canals in Oregon". Preliminary Report of the Inland Waterways Commission. 5250. Washington, DC: U.S. Government Printing Office. pp. 308–310.

- Wright, E.W., ed. (1895). "VIII ... The Willamette Falls Canal and Locks Company". Lewis & Dryden's Marine History of the Pacific Northwest. Portland, OR: Lewis and Dryden Printing Co. p. 163. LCCN 28001147.

- "Progress in Oregon". Oregon City Enterprise. January 31, 1873. p.1, col.3.

- Wright, E.W., ed. (1895). "III ... The James P. Flint on the Middle Columbia". Lewis & Dryden's Marine History of the Pacific Northwest. Portland, OR: Lewis and Dryden Printing Co. p.35, n.3. LCCN 28001147.

- Idaho State Historical Society (1922). "Captain Ephraim W. Baughman". Biennial Report of the Board of Trustees. 8. Boise, ID. p. 39.

- Huelat, Septimus (September 14, 1868). "Articles of incorporation ... Wallamet Falls Canal and Locks Company". The Weekly Enterprise. 3 (10). Oregon City, OR: Ireland, DeWitt Clinton (1836–1913) (published January 16, 1869). p.3, cols.5 & 6.

- Cross, Harvey E.; et al. (1893). "Report of the Special Committee Appointed to Consider a Plan for the Acquisition of the Locks on the Willamette River at Oregon City". Journal of the Senate. Salem, OR: State of Oregon, Legislative Assembly, Seventeenth Regular Session. pp. 660–672.

- Oregon Legislative Assembly, 5th Biennial Session (1868). "An Act to appropriate funds for the construction of a Steamboat Canal at Wallamet Falls". The Weekly Enterprise. 3 (7). Oregon City, OR: Ireland, DeWitt Clinton (1836–1913) (published December 26, 1868). p.3, col.6.

- Huelat, Septimus, secretary (January 16, 1869). "Circular of the Wallamet Falls Canal and Locks Company, of Clackamas County, Oregon". The Weekly Enterprise. 3 (10). Oregon City, OR: Ireland, DeWitt Clinton (1836–1913). p.3, cols.4 & 5.

- Mills, Randall V. (1947). Stern-wheelers up Columbia: A Century of Steamboating in the Oregon Country. Lincoln, NE: University of Nebraska. pp. 58–59, 142–143. ISBN 0-8032-5874-7. LCCN 77007161.

- Salem, OR (January 23, 1869). "Letter from Oregon: Ship Canal at Wallamet Falls". Sacramento Daily Union. 36 (5574) (published February 6, 1869). p.1, col.4.

- "New Advertisements". The Weekly Enterprise. Oregon City, OR. March 27, 1869. p.2, col.7.

- Corning, Howard McKinley (1973). "Lost Towns of Willamette Falls … Linn City, Terminal of Commerce". Willamette Landings: Ghost Towns of the River (2nd ed.). Portland, OR: Oregon Historical Society. pp. 32–49. ISBN 0875950426.

- Whiteaker, John; et al. (January 1, 1873). "Willamette Canal and Locks: Report of the Commissioners to Examine and Accept the works On Behalf of the State". Oregon City Enterprise. 7 (11). Noltner, Anthony A. (1838–1907) (published January 10, 1873). p.2, col.4.

- "Secretary Earhart's Reports … The Willamette falls canal and lock bonds …". Willamette Farmer. XII (31). Salem, OR: Willamette Farmer Publishing Co. September 17, 1880. p.5, col.4.

- "Canal and Lock Co". Weekly Enterprise. Oregon City, OR. December 16, 1870. p.2, col.3.

- The Secretary of War (December 19, 1899). "Examination and Survey of Canal and Locks at Willamette Falls, Willamette River, Oregon". United States Congressional Serial Set. 3974. Washington, DC: Government Printing Office.

- "Locking Wallamet Falls". Morning Oregonian. VIII (322). Portland, OR: Henry L. Pittock. January 5, 1869. p.3, col.1.

- Smith, Isaac W. (1872). "Canal and Locks — Engineer's Statement". Oregon City Enterprise. 6 (11). Noltner, Anthony A. (1838–1907) (published May 31, 1872). p.2, col.7.

- "Will the Canal and Locks be a Swindle?". Willamette Farmer. IV (12). Salem, OR: A.L. Stinson. May 11, 1872. p.4, col.1.

- Goldsmith, Bernard (January 18, 1871). "To Builders and Contractors ... Sealed proposals will be received until noon, March 1, 1871 ..." The Weekly Enterprise (bid solicitation). 5 (11). Oregon City, OR: Noltner, Anthony A. (1838–1907) (published January 20, 1871). p.2, col.6.

- "The Willamette Canal and Locks". The Weekly Enterprise. 5 (43). Oregon City, OR: Noltner, Anthony A. (1838–1907). September 1, 1871. p.2, col.1.

- "Disappeared. One of the contractors, Mr. Jordan, of the work to construct the locks ..." Oregon City Enterprise. 6 (2). Noltner, Anthony A. (1838–1907). November 17, 1871. p.3, col.1.

- "Oregon". Morning Oregonian. Portland, OR: Pittock, Henry L. July 27, 1872. p. 2.

- Smith, Isaac W. (1873). "Report of the Engineer of the Willamette Falls Canal & Lock Co". Willamette Farmer. V (19). Salem, OR (published June 28, 1873). p.3, cols.4 & 5.

- "Completed. From good authority we hear that the work on the canal and locks ..." Willamette Farmer. IV (43). Salem, OR. December 14, 1872. p.1, col.4.

- "The Locks and Canal. The Bulletin of Dec. 25th says it was expected that a steamer would pass ..." Willamette Farmer. IV (45). Salem, OR. December 28, 1872. p.8, col.2.

- "Accepted — Gov. Grover appointed ... commissioners to examine the locks ..." Oregon City Enterprise. 7 (10). Noltner, Anthony A. (1838–1907). January 3, 1873. p.3, col.1.

- "The Locks Completed: The First Boat Passed Through". Oregon City Enterprise. 7 (10). Noltner, Anthony A. (1838–1907). January 3, 1873. p.3, col.2.

- "The Locks Commissioners ... we met with members of the Board of Canals and Locks ..." Oregon City Enterprise (reprinting article from the Willamette Farmer.). XII (42). Dement, Frank S. August 8, 1878. p.2, col.2.

- "The Willamette Transportation And Locks Company have incorporated …". Oregon City Enterprise. 10 (11). Dement, Frank S. January 7, 1876. p.4, col.1.

- "Real Estate Transfers … Willamette Falls Canal and Locks Company to …". Oregon City Enterprise. 10 (21). Dement, Frank S. March 17, 1876. p.3, col.1.

- "City and County: Willamette Freights". Eugene City Guard (496). Buys, George J. May 5, 1877. p.3, col.1.

- "Veteran Oregon City Lock Tender Dies: John Chambers Well Known to Navigators of Willamette". Sunday Oregonian. XLVIII (32). Portland, OR. August 11, 1929. p.14, col.4.

- "State asks Share: Sues Portland General Electric Company: Claims it is Entitled to Ten Per Cent of the Profits on Tolls". Oregon City Enterprise. 28 (52). November 24, 1905. p.1, col.5.

- "The Fight for an Open Willamette River". Daily Capital Journal (Editorial). XIX (127). Salem, OR: Hofer, E., Col. June 17, 1909. p.2, col.1.

- "Says State Cannot Get Percentage: Judge Frazer Holds that Oregon Can't Collect Part of Profits of Oregon City Locks". Oregon Daily Journal. V (220). Portland, OR: Jackson, Charles Samuel. November 17, 1906. p. 1.

- Ives v. Smith, 4 Railway and Corp. L. J. 584, 585 (N.Y. Sup. December 4, 1888).

- "Two Uses of Water: Manufacturing and Navigation at the Falls: No Conflict Between Them: Engineers to Examine With View to Government Acquisition of Canal and Locks at Oregon City — Would Make River Free". Sunday Oregonian. Portland, OR. August 3, 1902. Part Two, Page 10.

- "View Canal Locks: United States Engineers Visit Oregon City". Morning Oregonian. XLII (13, 088). Portland, OR. November 22, 1902. p.10, col.1.

- "An End of Tolls: National Government May Buy Locks". Morning Oregonian. Portland, OR. October 24, 1904. p.14, col.1.

- "Oregon Notifies Taft: Copy of Willamette River Appropriation Bill Sent to Washington". East Oregonian. 20 (6, 108). Pendleton, OR. October 25, 1907. p.2, col.3.

- "Three Hurt at Oregon City". Morning Oregonian. XLIX (15, 135). Portland, OR. June 1, 1909. p.5 col.3.

- "Power Company Is Hit: Oversight in Assessment is No Relief in Tax Duty". Morning Oregonian. LI (15, 769). Portland, OR. June 11, 1011. p.5, col.3.

- "Lock Deed Awaited: Papers for Oregon City Project Some Place in Mail: Futile Search is Made: Closing of Transaction Delayed Until Documents Arrive — Transportation Company Has New Tariffs Ready". Morning Oregonian. XXXIV (17). Portland, OR. April 25, 1915. p. 6.

- "News Release 97–127" (Press release). U.S. Army Corps of Engineers. December 29, 1997. Archived from the original on January 16, 2009. Retrieved June 10, 2007.

- "Locks' Purchase May be Held Up". Morning Oregonian. XXXI (29). Portland, OR. July 21, 1912. p.8, col.1.

- "Linn City Record Lacking: Sale of Locks Still Hangs on Recovery of Town Survey". Morning Oregonian. LII (16, 127). Portland, OR. August 1, 1912. p. 16.

- "False Channel Idea: Wooden Flume to Carry Commerce at Oregon City". Morning Oregonian. VLI (17, 413). Portland, OR. September 13, 1916. p.14, col.3.

- "Big Wall Finished: Oregon City Locks Project of Concrete, 1280 feet long: Other Work May Wait". Morning Oregonian. LVII (17, 715). Portland, OR. September 1, 1917. p.16, col.3.

- The Sunday Oregonian, Metro Northwest Section, page 3, January 13, 2008

- Molly Young (April 25, 2011). "Willamette Falls Locks will remain closed to public boaters for the rest of the year". OregonLive. Retrieved July 12, 2018.

- Dungca, Nicole (October 28, 2009). "Second chance for Willamette Falls Locks, an Oregon treasure". OregonLive. Retrieved October 29, 2009.

- Miner, Colin (January 28, 2010). "Passengers welcome for trip through Willamette Falls locks". OregonLive. Retrieved January 28, 2010.

- "Lock Fest 2011 Canceled". Willamette Falls Heritage Foundation. April 12, 2011. Retrieved April 14, 2011.

- "Locks at Willamette Falls out of commission". Statesman Journal. Salem, Oregon. December 2, 2011. Retrieved December 2, 2011.

- "Endangered Willamette Falls Locks deserve a task force: Editorial". OregonLive. December 21, 2014. Retrieved January 12, 2015.

References

Books

- Corning, Howard M. (1956). Dictionary of Oregon History. Binford & Mort.

- Corning, Howard McKinley (1973). Willamette Landings: Ghost Towns of the River (2nd ed.). Portland, OR: Oregon Historical Society. ISBN 0875950426.

- Mills, Randall V. (1947). Stern-wheelers up Columbia: A Century of Steamboating in the Oregon Country. Lincoln NE: University of Nebraska. ISBN 0-8032-5874-7. LCCN 77007161.

- Wright, E.W., ed. (1895). Lewis & Dryden's Marine history of the Pacific Northwest. Portland, OR: Lewis and Dryden Printing Co. LCCN 28001147.

- Thompkins, Jim (2006). Oregon City. Arcadia Publishing. ISBN 1439634327.

Reports

- United States Congress (February 26, 1908). Preliminary Report of the Inland Waterways Commission. 5250. Washington, DC: U.S. Government Printing Office.

- Smith, Isaac W. (1873). "Report of the Engineer of the Willamette Falls Canal & Lock Co". Willamette Farmer. V (19). Salem, OR (published June 28, 1873). p.3, col.4.

- Cross, Harvey E.; et al. (1893). "Report of the Special Committee Appointed to Consider a Plan for the Acquisition of the Locks on the Willamette River at Oregon City". Journal of the Senate. Salem, OR: State of Oregon, Legislative Assembly, Seventeenth Regular Session. pp. 660–672.

- United States Army, Chief of Engineers (1922). Willamette River at Willamette Falls. Washington DC. p. 1907.

- The Secretary of War (December 19, 1899). "Examination and Survey of Canal and Locks at Willamette Falls, Willamette River, Oregon". United States Congressional Serial Set. 3974. Washington, DC: Government Printing Office.

Court cases

- Oregon v. Portland General Electric, 52 Or. 502 (Sup.Ct. November 17, 1908).

External links

- Army Corps of Engineers facts

- End of the Oregon Trail Interpretive Center website

- National Trust for Historic Preservation

- Willamette Falls Heritage Foundation

- Historic American Engineering Record (HAER) No. OR-1, "Willamette Falls Lock Chamber No.1, Willamette River, West Linn, Clackamas County, OR", 14 photos, 5 measured drawings, 2 photo caption pages