Williamite War in Ireland

The Williamite War in Ireland (1688–1691) (Irish: Cogadh an Dá Rí, "war of the two kings"),[4][5] was a conflict between Jacobite supporters of deposed monarch James II and Williamite supporters of his successor, William III. It is also called the Jacobite War in Ireland or the Williamite–Jacobite War in Ireland.

| Williamite War in Ireland | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the War of the Grand Alliance | |||||||

Battle of the Boyne between James II and William III, 11 July 1690, Jan van Huchtenburg | |||||||

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

|

|

| ||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

|

|

| ||||||

| Strength | |||||||

| 44,000[1] | 36,000[2]–39,000[1] | ||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

| 10,000 killed or died of disease[3] | 15,293 killed or died of disease, inc 2,000 irregulars[3] | ||||||

The proximate cause of the war was the Glorious Revolution of 1688, in which James, a Catholic, was overthrown as king of England, Ireland and Scotland and replaced by his Protestant daughter Mary and nephew and son-in-law William, ruling as joint monarchs. James's supporters initially retained control of Ireland, which he hoped to use as a base for a campaign to reclaim all three kingdoms. The conflict in Ireland also involved long-standing domestic issues of land ownership, religion and civic rights; most Irish Catholics supported James in the hope he would address their grievances. A small number of English and Scottish Catholics, and Protestants of the established Church in Ireland, also fought on the Jacobite side,[6][7] while most Irish Protestants supported or actively fought for William's regime.

While the war's Irish name emphasises its aspect as a domestic conflict between James and William, some contemporaries and many modern commentators have viewed it as part of a wider European conflict known as the Nine Years' War or War of the Grand Alliance in which William, as Stadtholder of the Dutch Republic, led a multi-national coalition against France under Louis XIV.[4][5] William's deposition of James was partly driven by his need to control and mobilise English military and commercial power, while Louis provided limited material support to the Jacobites: both sides were aware of the Irish war's potential to divert military resources from the Continent.

The war began with a series of skirmishes between James's Irish Army, which had stayed loyal in 1688, and militia forces raised by Irish Protestants: they culminated in the Siege of Derry, where the Jacobites failed to regain control of one of the north's key towns. William landed a force including English, Scottish, Dutch, Danish and other troops to put down Jacobite resistance. James left Ireland after a reverse at the Battle of the Boyne in 1690, as did William after a successful Jacobite defence of Limerick; the remaining Jacobite forces were decisively defeated at the Battle of Aughrim in 1691, and negotiated terms in the Treaty of Limerick.

A contemporary witness, George Story, calculated that the war had claimed 100,000 lives through sickness, famine, and in battle.[3] Subsequent Jacobite risings were confined to Scotland and England, but the war was to have a lasting effect on the political and cultural landscape of Ireland, confirming British and Protestant rule over the country for over two centuries. While the Treaty of Limerick had offered a series of guarantees to Catholics, subsequent extension of the Penal Laws, particularly during the War of the Spanish Succession, would further erode their civic rights.

The Williamite victories at Derry and the Boyne are still celebrated by some, mostly Ulster Protestant, unionists in Ireland today.

Background; Glorious Revolution

In March 1689, James II & VII landed in Ireland with French military support, seeking to regain the thrones of England, Ireland and Scotland, after being deposed in the 1688 Glorious Revolution. Despite his Catholicism, James became king in 1685 with widespread support in all three kingdoms, due to fear of civil war if he were bypassed; by 1688, it seemed only his removal could prevent one.[8]

When the Parliaments of Scotland and England refused to pass measures of tolerance for Catholics and Nonconformists in 1685, James suspended them and thereafter ruled by decree.[9] His increasingly authoritarian approach undercut his supporters and caused great concern but it took two events in June 1688 for dissent to turn into a crisis. On the 10th, the birth of James Francis Edward created a Catholic heir and excluded James' Protestant daughter Mary and her husband William of Orange. The prosecution of the Seven Bishops for seditious libel was seen as an assault on the Church of England and their acquittal on 30 June destroyed James' political authority in England and Scotland.[10]

In Europe, the Dutch Republic and its allies were on the brink of war with France, which made securing English resources vital. French troops attacked the Rhineland in late September, launching the 1688–1697 Nine Years' War; on 5 November, William landed in South-West England, James' army deserted and he fled to France on 23 December.

There was wider support for James in Ireland, where around 75% of the population were Catholic, although in Ulster Protestants comprised nearly 50%.[11] James's associate Richard Talbot, Earl of Tyrconnell became Lord Deputy of Ireland in 1687 and began a rapid programme of appointing Catholics to the army and other public offices. By February 1689, the Irish army was almost exclusively Catholic, albeit poorly equipped, half-trained and unpaid.[12]

However, a long-standing problem for the Stuarts was that while Irish Catholics were one of their main bases of support, concessions threatened Protestant support in all three kingdoms, especially England. Reversing the land confiscations of the 1650s was non-negotiable for Irish Catholics, whose ownership declined from 90% in 1600 to 22% by 1685, but changes were viewed with extreme hostility by the Protestants who were its beneficiaries. Pre-1688, this meant James often backed Protestants in disputes over land, and adopted commercial policies favouring English, rather than Irish, merchants.[13]

As a result, the 1662 Settlement made few changes and primarily benefited the Old English Catholic elite. This faction, led by Tyrconnell's brother-in-law, the Earl of Limerick, feared they would lose from a war either way, and preferred a minimalist solution that was rejected by the majority.[14]

Finally, demands for Irish autonomy clashed with Stuart ideology, first set out by James VI and I in 1603, which his successors followed with great consistency, including Prince Charles in 1745. It envisaged a unitary state of England, Scotland and Ireland, ruled by a monarch whose authority came from God and where the role of Parliament and the church was to obey.[15] Like Louis XIV, James claimed the right to appoint Catholic bishops and clergy in his kingdoms, an alteration to existing practice that caused conflict with Pope Innocent XI.[16] Innocent's family bank lent William money, a fact kept secret for over three centuries, but his opposition also impacted support from other Catholic leaders. On 13 April 1689, Louis wrote to D'Avaux that "the Pope sets so bad an example to all the other Catholic princes, we can scarcely hope [for their help]".[17]

1688–1689: the North

James was so confident of Ireland that in September he ordered 2,500 troops, or around 40% of the Irish army, transferred to England.[18] This deprived Tyrconnell of vital trained personnel, while their presence led to near mutiny in several of James' most reliable English units.[19] Many of the Irish rank and file were arrested after William's landing and later sent to serve under Emperor Leopold in the Austrian–Ottoman War.[20]

News of the landing was greeted with Williamite demonstrations in Belfast, offset by a more cautious response elsewhere. Arthur Rawdon, who later organised the Army of the North, had offered to fight for James against Monmouth in 1685 and did not commit to William until March 1689.[21] Protestants were concentrated in Ulster and urban centres such as Sligo and Dublin, which Tyrconnell sought to secure with Catholic units of the Irish army.[22]

Catholic troops under the Earl of Antrim were refused entry to Derry on 7 December, Enniskillen doing the same a few days later. A significant factor was the unsettled political situation; Derry's Protestant leaders simultaneously declared their "duty and loyalty to our sovereign lord, the King" and the siege did not begin until April. Many Irish Protestants initially appealed to James for protection, not William.[23]

Apparently shaken by the speed of James's fall, Tyrconnell opened negotiations with William, although this may have been a delaying tactic.[24] His wife, Frances Talbot, was the elder sister of Sarah Churchill, whose husband Marlborough was a key member of the English military conspiracy against James. One of those transferred to England in September was Richard Hamilton, an Irish Catholic professional soldier. Confined in the Tower of London after James' flight, in January William sent him to negotiate with Tyrconnell, a mission he abandoned once back in Ireland.[25]

In January, warrants were issued for the recruitment of another 40,000 levies, almost entirely Catholic and organised along standard regimental lines.[26] By spring 1689, the army theoretically had around 36,000 men, although experienced officers remained in short supply.[27] Paying, equipping and training this number was impossible and many were organised as Rapparees or irregulars, largely beyond Tyrconnell's control.[12] Despite assurances of protection, the easiest way to obtain supplies or money was to confiscate it from Protestants; many fled to the North or England, spreading "predictions of impending catastrophe".[18]

Fears grew as areas outside the towns became increasingly lawless, exacerbated when Dublin Castle ordered Protestant militia to be disarmed.[28] This caused an exodus from the countryside; the population of Derry grew from 2,500 in December to over 30,000 by April.[29] Doubts over the ability of Tyrconnell's regime to ensure law and order was not confined to Protestants; many Catholics also sought security abroad or in large towns.[30] On 8 March, the English Parliament approved funding for an Irish expeditionary force of 22,230 men, composed of new levies and European mercenaries.[31]

James landed in Kinsale on 12 March, accompanied by French regulars under de Rosen, along with English, Scottish and Irish volunteers.[32] Hamilton was appointed Jacobite commander in the North and on 14 March secured eastern Ulster by routing a Williamite militia at Dromore. On 11 April, Viscount Dundee launched a Jacobite rising in Scotland; on 18th, James joined the siege of Derry and on 29th, the French landed another 1,500–3,000 Jacobites at Bantry Bay.[32] When reinforcements from England reached Derry in mid-April, governor Robert Lundy advised them to return, claiming the city was indefensible. Their commanders, Richards and Cunningham, were dismissed by William for cowardice and Lundy fled the town in disguise.[25]

By spring 1689, the new regime was threatened by Jacobite advances in Ireland and Western Scotland. William viewed Ireland as a French proxy invasion, best dealt with by attacking France; he reluctantly agreed to divert resources only because 'abandoning' beleaguered Irish Protestants was politically unacceptable in England and Scotland.[33] On the other hand, French involvement in Ireland was a key factor in England's decision to join the Grand Alliance and become part of the wider European war.[34]

The Jacobite focus on western Ulster, specifically Derry and Enniskillen, was a strategic error. Control of eastern Ulster was of greater significance, since it allowed mutual support between Irish and Scots Jacobites and made resupply from England far more difficult.[35] By mid May, the Williamite position had improved; on 16th, government forces retained control of Kintyre, cutting direct links between Scotland and Ireland. The main Jacobite army was stuck outside Derry, its French contingent proving more unpopular with their Irish colleagues than their opponents.[23] On 11 June, four battalions of Williamite reinforcements under the tough and experienced Percy Kirke arrived on the Foyle, north of Derry.[36]

The war in the North turned on three events in the last week of July. Dundee's victory at Killiecrankie on 27th was offset by his own death and heavy losses among his troops, ending the Scottish rising as a serious threat. On the 28th, Kirke's forces broke the Jacobite blockade with naval support and raised the siege of Derry; the besiegers fired the surrounding countryside and retreated south. On the 31st, a Jacobite attack on Enniskillen was defeated at Newtownbutler; over 1,500 men were killed and its leader Mountcashel captured. From a position of virtual domination, the Jacobites lost their hold on Ulster within a week.[37]

On 13 August, Schomberg landed in Belfast Lough with the main Williamite army; by the end of the month, he had more than 20,000 men.[38] Carrickfergus fell on 27 August; James insisted on holding Dundalk, against the advice of his French advisors who wanted to retreat beyond the Shannon. Tyrconnell was pessimistic about their chances but an opportunity for Schomberg to end the war by taking Dundalk was missed, largely due to a complete failure of logistics.[39]

Ireland was a relatively poor country with a small population, obliging both armies to depend on external support.[40] While this ultimately proved a greater problem for the Jacobites, Schomberg's men lacked tents, coal, food and clothing, largely because his inexperienced commissary agent in Chester could not charter enough ships. This was worsened by choosing a campsite on low, marshy ground, which autumn rains and lack of hygiene quickly turned into a stinking swamp.[41] Nearly 6,000 men died from disease before Schomberg ordered a withdrawal into winter quarters in November.[42]

Inspecting the abandoned camp, John Stevens, an English Catholic serving with the Grand Prior's Regiment, recorded that "besides the infinite number of graves a vast number of dead bodies was found there unburied, and not a few yet breathing but almost devoured with lice and other vermin. This spectacle not a little astonished such of our men as ventured in amongst them".[43]

Jacobite political and strategic objectives 1689-1690

_by_Hyacinthe_Rigaud.jpg.webp)

The Jacobites were undermined by differing political and strategic objectives, reflected in the Irish Parliament that sat from May to July. Since no elections were held in Fermanagh and Donegal, the Commons was 70 members short and largely composed of Catholics; of these, a minority were Gaelic-speakers or 'Old Irish, the majority being Old English.[44] Five Protestant peers and four Church of Ireland bishops sat in the Lords, with Anthony Dopping, Bishop of Meath acting as leader of the opposition.[45]

Dubbed the "Patriot Parliament" by 19th century nationalist historian Charles Duffy, in reality it was deeply divided.[46] James viewed the English throne as his main objective and every concession made in Ireland potentially weakened his position in England and Scotland. In the early stages of the war, Protestant Jacobite support was more significant than often appreciated and included many members of the established Church of Ireland, the most prominent being Viscount Mountjoy.[47] His opposition to Irish autonomy meant James made concessions with great reluctance and despite his own Catholicism, insisted on the rights of the established church.[48]

Tyrconnell viewed the restoration of James as secondary to an autonomous Ireland, although there is little evidence to support suggestions he held talks with Louis XIV on a French-backed satellite state.[49] He represented the minority of Catholics who benefited from the 1662 Land Settlement and had no desire to change it; led by the Earl of Limerick, this faction urged a compromise settlement with William in January.[14] This placed them in opposition to the Old Irish, a majority in the country but a minority in Parliament, whose main demand was restoration of lands confiscated after the Cromwellian conquest.[50]

Significant factions within the Irish Parliament preferred to negotiate, which meant avoiding combat to preserve the army and retain as much territory as possible. Since England was his main objective, James saw Ireland as a distraction; a cross-Channel invasion was the only viable option and the French suggestion of doing so via the Irish Sea ignored reality. First, history showed involving Ireland was the best way to strengthen English opposition; this meant victory might actually weaken his chances, although as James pointed out, the French provided only enough to keep the war going, not win it.[51] Second, the French navy could neither save Ulster or even supply their own forces, making it unlikely they could control the Irish Sea long enough to land troops in the face of a hostile population.[52]

Peripheral rebellions in Ireland and Scotland were a cost-effective way for France to divert British resources from Europe. This meant prolonging the war was more useful than winning it, although potentially devastating for the local populace, a dilemma that resurfaced in the 1745 Scottish Rising.[53] In 1689, the French envoy d'Avaux urged the Jacobites to withdraw beyond the Shannon, first destroying everything in between, including Dublin. Unsurprisingly, this suggestion was rejected, while the Irish were united in their dislike of the French in general and d'Avaux in particular. The feeling was mutual; when replaced in April 1690, d'Avaux told his successor Lauzun the Irish were 'a poor-spirited and cowardly people, whose soldiers never fight and whose officers will never obey orders.'[54]

1690: the Boyne and Limerick

In April 1690, an additional 6,000 French regulars arrived, in exchange for Mountcashel and 5,387 of the Irish army's best troops, who were sent to France.[55] To retain as much territory as possible, the Jacobites held a line along the River Boyne, first destroying or removing crops and livestock to the north. This reduced the local population to utter misery; a French official recorded his horror at seeing them "eating grass like horses" or lying dead at the roadside.[56] It took over fifty years for the area around Drogheda to recover from this devastation.[57]

Faced by English demands to resolve the position in Ireland, William decided to take personal command and commit the majority of his available forces there, irrespective of the military situation in Flanders.[42] On 14 June 1690, 300 ships arrived in Belfast Lough carrying nearly 31,000 men, a combination of Dutch, English and Danish regiments.[58] Parliament backed him with increased funding and the issues faced by Schomberg were remedied, transportation costs alone rising from £15,000 in 1689 to over £100,000 in 1690.[59]

The Jacobites established defensive positions on the south bank of the Boyne at Oldbridge, outside Drogheda.[55] On 1 July, William crossed the river in several places, forcing them to retreat but the battle was not decisive. Total dead on both sides was under 2,000, one being Schomberg; weakened by desertion, the Jacobite army retreated to Limerick and William entered Dublin unopposed.[60]

Elsewhere, victory at Fleurus on 1 July gave the French control of Flanders; on the same day as the Boyne, they defeated a combined Anglo-Dutch fleet at Beachy Head, causing panic in England. As a former English naval commander, James recognised control of the Channel was a rare opportunity and returned to France to urge an immediate invasion.[61] However, the French failed to follow up their victory and by August, the Anglo-Dutch fleet had regained command of the sea.[62]

Tyrconnell had spent the winter of 1689 to 1690 urging Louis XIV to support a "descent on England" and avoid fighting on Irish soil. His requests were rejected; an invasion required enormous expenditure and Louis trusted neither James nor his English supporters.[63] While there were sound strategic reasons for his hurried departure, which were backed by his senior commanders, James has gone down in Irish history as Séamus an Chaca or "James the beshitten/coward".[64]

An opportunity to end the war was missed when William overestimated the strength of his position. The Declaration of Finglas of 17 July excluded Jacobite officers and the Catholic landed class from a general pardon, encouraging them to continue fighting. Shortly afterwards, James Douglas and 7,500 men tried to break the Jacobite defensive line along the Shannon by taking Athlone; they lacked siege artillery and were forced to withdraw.[65]

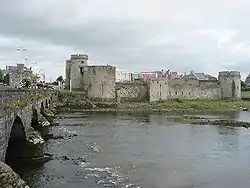

Limerick, strategic key to the west of Ireland, became William's next objective, the Jacobites concentrating the bulk of their forces in the city.[44] A detachment under Marlborough captured Cork and Kinsale but Limerick repulsed a series of assaults, inflicting heavy casualties.[66] Cavalry raids led by Patrick Sarsfield destroyed William's artillery train and heavy rain prevented replacements. Faced by multiple threats in mainland Europe, William withdrew and left Ireland in late 1690, the Jacobites retaining large parts of western Ireland.[67]

Dutch general de Ginkell assumed command, based at Kilkenny, with Douglas in Ulster and the Danes under Württemberg at Waterford. Protestant administration was re-established in the counties held by Williamites, with arrests and confiscation of Jacobite estates, intended to reward William's supporters. Ginkel pointed out doing so in cash, not land, was cheaper than a month of war and urged more generous terms.[68]

On 24 July, a letter from James confirmed ships were on their way to evacuate the French brigade and any others who wanted to leave; he also released his Irish officers from their oaths, allowing them to seek a negotiated end to the war. Tyrconnell and the French troops sailed from Galway in early September; James's inexperienced illegitimate son Berwick was left in command, supported by a council of officers composed of Thomas Maxwell, Dominic Sheldon, John Hamilton and Sarsfield.[69]

Tyrconnell hoped to obtain sufficient French support to extend the conflict and gain better terms, which he told Louis could be done with limited numbers of French troops. A negotiated peace also required him to reduce the influence of the pro-war party, led by Sarsfield, who was increasingly popular with the army. He told James the pro-war group wanted Irish autonomy or even independence, while he wished to see Ireland linked firmly to England; to do so, he needed arms, money and an 'experienced' French general to replace Sarsfield and Berwick.[67]

1691: Athlone, Aughrim and the Second Siege of Limerick

_(2).jpg.webp)

By late 1690, divisions between the Jacobite "Peace Party" and "War Party" had widened.[70] Those who supported Tyrconnell's efforts to negotiate with William included senior officers Thomas Maxwell and John Hamilton, in addition to political figures such as Lord Riverston and Denis Daly.[71] Sarsfield's "War Party" argued William could still be defeated; while once characterised as representing the 'Old Irish' interest, its leaders included the English officer Dorrington and 'Old English' Purcell and Luttrell.[71]

Encouraged by William's failure to take Limerick and looking to reduce Tyrconnell's influence, Sarsfield's faction appealed directly to Louis XIV requesting that Tyrconnell and Berwick were removed from office.[72] They also asked for substantial French military aid, although this was unlikely as the French regime saw Flanders, the Rhine, and Italy as greater strategic priorities.[44][70] Ginkell had finally obtained William's permission to offer the Jacobites moderate terms of surrender, including a guarantee of religious toleration,[73] but when in December the "Peace Party" made moves to accept, Sarsfield demanded that Berwick have Hamilton, Riverston and Daly arrested. Berwick complied, although likely with the tacit approval of Tyrconnell, who returned from France to try and regain control by offering Sarsfield concessions.[70]

Deeply alarmed by the rift between his Irish supporters, James was persuaded to request further military support directly from Louis.[74] Louis dispatched general the Marquis de St Ruth to replace Berwick as commander of the Irish Army, with secret instructions to assess the situation and help Louis make a decision on whether to send additional military aid.[74] St Ruth, accompanied by lieutenant-generals de Tessé and d'Usson, arrived at Limerick on 9 May; they brought sufficient arms, corn and meal to sustain the army until the autumn, but no troops or money.[75]

By late spring, concerned that a French convoy could land further reinforcements at Galway or Limerick, Ginkell began making preparations to enter the field as quickly as possible.[76] During May, both sides began assembling their forces for a summer campaign, the Jacobites at Limerick and the Williamites at Mullingar, while low-level skirmishing continued.

On 16 June, Ginkell's cavalry began reconnoitring from Ballymore towards Athlone. St Ruth had initially strung out his forces behind the line of the Shannon, but by 19 June he realised Athlone was the target and began concentrating his troops west of the town.[77] Ginkell breached the Jacobite lines of defence and took Athlone on 30 June after a short but bloody siege, taking Maxwell prisoner; St Ruth failed in his attempts to relieve the garrison and fell back to the west.[78]

Athlone was seen as a significant victory for William's forces, as it was believed that St Ruth's army would probably collapse if the Shannon was crossed.[77] The Lords Justice in Dublin issued a proclamation offering generous terms for Jacobites who surrendered, including a free pardon, restoration of forfeited estates, and the offer of similar or higher rank and pay if they wished to join William's army.[79] The Jacobite command fell apart in mutual recriminations: Sarsfield's faction accused Maxwell, a follower of Tyrconnell, of treachery, while St Ruth's subordinate d'Usson sided with Tyrconnell, who appointed him governor of Galway.[78]

Unaware of the location of St Ruth's main army and assuming he was outnumbered, on 10 July Ginkell continued a cautious advance through Ballinasloe down the main Limerick and Galway road.[80] St Ruth's initial plan, endorsed by Tyrconnell, had been to fall back on Limerick and force the Williamites into another year of campaigning, but wishing to redeem his errors at Athlone he appears to have instead decided to force a decisive battle.[81] Ginkell, with 20,000 men, found his way blocked by St Ruth's similarly sized army at Aughrim on the early morning of 12 July. Despite a brave and tenacious defence by the inexperienced Irish infantry, the Battle of Aughrim would see St Ruth dead, many senior Jacobite officers captured or killed, and the Jacobite army shattered.[81]

D'Usson succeeded as overall commander: he surrendered Galway on 21 July, on advantageous terms. Following Aughrim the remnants of St Ruth's army retreated to the mountains before regrouping under Sarsfield's command at Limerick, where the defences were still in the process of being repaired: many of the Jacobite infantry regiments were seriously depleted, although some stragglers arrived later.[82] Tyrconnell, who had been sick for some time, died at Limerick shortly afterwards, depriving the Jacobites of their main negotiator. Sarsfield and the Jacobites' main army surrendered at Limerick in October after a short siege.

Treaty of Limerick and aftermath

Sarsfield, now the senior Jacobite commander, and Ginkell signed the Treaty of Limerick on 3 October 1691. It promised that Catholics would remain free to practice their religion and gave legal protection to any Jacobites willing to stay in Ireland and give an oath of loyalty to William and Mary, although the estates of those killed prior to the treaty were still liable to forfeiture.

The treaty also agreed to Sarsfield's demand that those still serving in the Jacobite army could leave for France. Popularly known in Ireland as the "Flight of the Wild Geese", the process began almost immediately, using English ships sailing from Cork; French ships completed it by December.[83] Modern estimates suggest that around 19,000 soldiers and rapparees departed: women and children brought the figure to slightly over 20,000, or about one per cent of Ireland's population.[83] Story alleged that some of the soldiers had to be forced on board the ships when they learned they would be joining the French. Most were unable to bring or to contact their families and many appear to have deserted en route from Limerick to Cork.[83]

The "Wild Geese" were initially formed into James II's army in exile. After James's death, they were merged into France's Irish Brigade, which had been set up in 1689 using the 6,000 troops accompanying Mountcashel. Disbanded Jacobites still presented a considerable risk to security in Ireland and despite resistance from the English and Irish parliaments, William continued to encourage them to join his own army; by the end of 1693 a further 3,650 former Jacobites had joined William's forces fighting on the Continent. [84] The Lord Lieutenant Viscount Sidney eventually restricted enlistment to "known Protestants", upon which the last remnants of the Jacobite army still in Ireland were sent home with a financial inducement to keep the peace.[84]

In the interim the English legislature, possibly acting under pressure from Irish Protestant refugees in London, passed a 1691 Act "for the Abrogating the Oath of Supremacy in Ireland and Appointing other Oaths".[85] This required anyone taking the Oath of Supremacy, such as when practising law, as a physician, or when taking a seat in the Irish Parliament, to deny transubstantiation; it effectively barred all Catholics, although included a clause exempting beneficiaries of the articles of Limerick in some circumstances.[85] Despite this, many Protestants were initially outraged by their perception that the treaty had left the Jacobites "immune to the penalties of defeat".[86] The fact that the administration chose to forbid searches for Jacobite arms and horses in order to prevent the settling of private scores was taken as evidence of pro-Catholic bias,[86] and it was even rumoured that the Lord Chancellor Sir Charles Porter was a "secret Jacobite".[86]

Continuing fears over Catholics' potential support of a French invasion and the appointment in 1695 of Capell as Lord Deputy saw a change of attitude. The same year, the Irish Parliament passed the Disarming Act, forbidding Catholics other than the Limerick and Galway 'articlemen' to own a weapon or a horse worth more than £5.[86][87] A second 1695 bill, designed to deter Irish Catholics "from their foreign correspondency and dependency" and aimed particularly at the country's "English ancient families", restrained Catholics from educating their children abroad.[88] Catholic gentry saw such actions as a serious breach of faith, summed up by the phrase cuimhnigí Luimneach agus feall na Sassanaigh ("remember Limerick and Saxon perfidy") supposedly used in later years by the exiles of the Irish Brigade. However, despite later extension of the penal laws, the 'articlemen' of Limerick, Galway, Drogheda and other garrisons subject to Williamite articles of surrender generally stayed exempt for the remainder of their lives.[89]

Long-term effects

The Williamite victory in the war in Ireland had two main long-term results. The first was that it ensured James II would not regain his thrones in England, Ireland, and Scotland by military means. The second was that it ensured closer British and Protestant dominance over Ireland. Until the nineteenth century, Ireland was ruled by what became known as the "Protestant Ascendancy", the mostly Protestant ruling class. The majority Irish Catholic community and the Ulster-Scots Presbyterian community were systematically excluded from power, which was based on land ownership.

For over a century after the war, Irish Catholics maintained a sentimental attachment to the Jacobite cause, portraying James and the Stuarts as the rightful monarchs who would have given a just settlement to Ireland, including self-government, restoration of confiscated lands and tolerance for Catholicism. Thousands of Irish soldiers left the country to serve the Stuart monarchs in the Spanish and French armies. Until 1766 France and the Papacy remained committed to restoring the Stuarts to their British Kingdoms, at least one composite Irish battalion (500 men) drawn from Irish soldiers in the French service fought on the Jacobite side in the Scottish Jacobite uprisings up to the Battle of Culloden in 1746.

The war also began the penetration of the Irish Protestant gentry into the British army's officer corps; by the 1770s Irish Protestants made up about one third of the officer corps as a whole, a number hugely disproportionate to their population.[90]

Protestants portrayed the Williamite victory as a triumph for religious and civil liberty. Triumphant murals of King William still controversially adorn gable walls in Ulster, and the defeat of the Catholics in the Williamite war are still commemorated by Protestant Unionists, by the Orange Order on the Twelfth of July.

See also

References

- Chandler (2003), Marlborough as Military Commander, p. 35

- Bartlett & Jeffery 1997, p. 190.

- Manning 2006, p. 398.

- Maguire 1990, p. 2.

- O Ciardha, 2002 & p.52.

- Hayton 2004, p. 22.

- Harris 2007, pp. 435–436.

- Wormsley 2015, p. 189.

- Miller 1978, pp. 156–157.

- Harris 2005, pp. 235–236.

- Harris 2005, pp. 88–90.

- Harris 2005, p. 426.

- Harris 2005, pp. 106–108.

- Harris 2005, p. 436.

- Stephen 2010, pp. 55–58.

- Miller 2001, p. 153.

- Widderow 1873, p. 3.

- Childs 2007, p. 3.

- Miller 1978, p. 196.

- Lenihan 2001, p. 16.

- Gillespie 1992, p. 127.

- Hayes-McCoy 1942, pp. 4–5.

- Gillespie 1992, p. 131.

- Szechi 1994, pp. 42–44.

- Childs 1987, p. 16.

- Hayes-McCoy 1942, p. 6.

- Bartlett & Jeffery 1997, pp. 189–190.

- Simms 1986, p. 169.

- "The Siege of Derry 1688–1689". Ulster genealogy and local history blog. Retrieved 19 July 2019.

- Gillespie 1992, p. 130.

- Bartlett & Jeffery 1997, p. 193.

- Bartlett & Jeffery 1997, p. 198.

- Szechi 1994, pp. 43–45.

- Bartlett & Jeffery 1997, p. 189.

- Lenihan 2001, p. 18.

- Childs 2007, p. 114.

- Childs 2007, p. 145.

- Lenihan 2001, p. 202.

- Lenihan 2001, p. 203.

- Childs 2007, p. 17.

- Lenihan 2001, p. 204.

- Bartlett & Jeffery 1997, p. 195.

- Stevens, p. 96.

- Szechi 1994, p. 47.

- Moody, Martin & Byrne 2009, p. 489.

- Szechi 1994, p. 44.

- Harris 2005, p. 435.

- Moody, Martin & Byrne 2009, p. 490.

- Hayton 1991, p. 201.

- Szechi 1994, p. 48.

- Clarke 1816, p. 387.

- Pearsall 1986, p. 113.

- Zimmerman 2003, p. 133.

- Childs 2007, p. 197.

- Bartlett & Jeffery 1997, p. 201.

- Connolly 2008, p. 191.

- O'Sullivan 1992, p. 435.

- Bartlett & Jeffery 1997, p. 196.

- Lenihan 2001, p. 205.

- Harris 2005, p. 446.

- Chandler 2003, p. 35.

- Lynn 1999, p. 215.

- Hayton 1991, p. 202.

- Moylan 1996, p. 234.

- Childs 2009, pp. 232–233.

- Szechi 1994, pp. 47–48.

- Childs 2009, pp. 259–260.

- Bartlett & Jeffery 1997, p. 205.

- Childs 2009, pp. 250–251.

- Hayton 2004, p. 27.

- Bradshaw 2016, p. 221.

- Hayton 2004, p. 28.

- Childs 2007, p. 293.

- Childs 2007, p. 279.

- Childs 2007, p. 295.

- Childs 2007, p. 304.

- Childs 2007, p. 316.

- Childs 2007, pp. 326–327.

- Childs 2007, p. 331.

- Childs 2007, p. 332.

- Doherty 1995.

- Murtagh 1953, p. 11.

- Manning 2006, p. 397.

- McGrath 1996, p. 30.

- Kinsella 2009, p. 20.

- Bartlett & Jeffery 1997, p. 238.

- Kinsella 2009, p. 21.

- McGrath 1996, p. 44.

- Kinsella 2009, pp. 34–35.

- Bartlett & Jeffery 1997, pp. 216, 218.

Sources

- Bartlett, Thomas; Jeffery, Keith (1997). A Military History of Ireland. Cambridge UP.

- Bradshaw, Brendan (2016). And so began the Irish Nation: Nationality, National Consciousness and Nationalism in Pre-modern Ireland. Routledge. ISBN 978-1472442567.

- Chandler, David G. (2003). Marlborough as Military Commander. Spellmount Ltd. ISBN 978-1-86227-195-1.

- Childs, John (2007). The Williamite Wars in Ireland 1688 – 1691. London: Hambledon Continuum Press. ISBN 978-1-85285-573-4.

- Childs, John (1987). The British Army of William III, 1689–1702. Manchester University Press. ISBN 978-0719019876.

- Clarke, JS (1816). The Life of James the Second, King of England, Collected Out of Memoirs Writ of His Own Hand, Vol. 2 of 2 (2017 ed.). Forgotten Books. ISBN 978-0265170588.

- Connolly, S.J. (2008). Divided Kingdom: Ireland 1630–1800. Oxford UP.

- Doherty, Richard (Autumn 1995). "The Battle of Aughrim". Early Modern History (1500–1700). 3 (3).

- Gillespie, Raymond (1992). "The Irish Protestants and James II, 1688–90". Irish Historical Studies. 28 (110): 124–133. doi:10.1017/S0021121400010671. JSTOR 30008314.

- Harris, Tim (2005). Revolution: The Great Crisis of the British Monarchy, 1685–1720 (2007 ed.). Penguin. ISBN 978-0141016528.

- Hayes-McCoy, G. A. (1942). "The Battle of Aughrim". Journal of the Galway Archaeological and Historical Society. 20 (1).

- Hayton, David (2004). Ruling Ireland, 1685–1742: Politics, Politicians and Parties. Boydell.

- Hayton, DW (author), Israel, Jonathan (ed) (1991). The Williamite Revolution in Ireland 1688–1691 in The Anglo-Dutch Moment: Essays on the Glorious Revolution and Its World Impact (2008 ed.). Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0521390750.CS1 maint: extra text: authors list (link)

- Kinsella, Eoin (2009). "In pursuit of a positive construction: Irish Catholics and the Williamite articles of surrender, 1690–1701". Eighteenth-Century Ireland. 24.

- Lenihan, Padraig (2001). Conquest and Resistance: War in Seventeenth-Century Ireland. Brill. ISBN 978-9004117433.

- Lenihan, Padraig (2003). Battle of the Boyne 1690. Gloucester. ISBN 978-0-7524-2597-9.

- Lynn, John (1996). The Wars of Louis XIV, 1667–1714 (Modern Wars in Perspective). Longman. ISBN 978-0582056299.;

- Magennis, Eoin (1998). "A 'Beleaguered Protestant'?: Walter Harris and the Writing of Fiction Unmasked in Mid-18th-Century Ireland". Eighteenth-Century Ireland. 13: 86–111. JSTOR 30064327.

- Maguire, William A. (1990). Kings in Conflict: the Revolutionary War in Ireland and its Aftermath 1688–1750. Blackstaff.

- Manning, Roger (2006). An Apprenticeship in Arms: The Origins of the British Army 1585–1702. Oxford UP.

- McGarry, Stephen (2014). Irish Brigades Abroad. Dublin. ISBN 978-1-845887-995.

- McGrath, Charles Ivar (1996). "Securing the Protestant Interest: The Origins and Purpose of the Penal Laws of 1695". Irish Historical Studies. 30 (117).

- Miller, John (1978). James II; A study in kingship (1991 ed.). Methuen. ISBN 978-0413652904.

- Moody; Martin; Byrne, eds. (2009). A New History of Ireland: Volume III: Early Modern Ireland 1534–1691. OUP. ISBN 9780198202424.

- Moylan, Seamas (1996). The Language of Kilkenny: Lexicon, Semantics, Structures. ISBN 9780906602706.

- Murtagh, Diarmuid (1953). "Louth Regiments in the Irish Jacobite Army". Journal of the County Louth Archaeological Society. 13 (1).

- O'Sullivan, Harold (1992). "The Jacobite Ascendancy and Williamite Revolution and Confiscations in County Louth 1684–1701". Journal of the County Louth Archaeological and Historical Society. 4 (22): 430–445. doi:10.2307/27729726. JSTOR 27729726.

- Pearsall, AWH (1986). "The Royal Navy and trade protection 1688–1714". Renaissance and Modern Studies. 30 (1): 109–123. doi:10.1080/14735788609366499.

- Simms, J.G (1969). Jacobite Ireland. London. ISBN 978-1-85182-553-0.

- Simms, JG (1986). War and Politics in Ireland, 1649-173. Continnuum-3PL. ISBN 978-0907628729.

- Stephen, Jeffrey (January 2010). "Scottish Nationalism and Stuart Unionism". Journal of British Studies. 49 (1, Scottish Special).

- Stevens, John. The journal of John Stevens, containing a brief account of the war in Ireland, 1689–1691. University College, Cork.

- Szechi, Daniel (1994). The Jacobites: Britain and Europe 1688–1788. Manchester University Press. ISBN 9780719037740.

- Wauchope, Piers (1992). Patrick Sarsfield and the Williamite War. Dublin. ISBN 978-0-7165-2476-2.

- Wilson, Philip (1903). . In O'Brien, R. Barry (ed.). Studies in Irish History, 1649–1775. Dublin: Browne and Nolan. pp. 1–65.

- Wormsley, David (2015). James II: The Last Catholic King. Allen Lane. ISBN 978-0141977065.