Wollemia

Wollemia is a genus of coniferous tree in the family Araucariaceae. Wollemia was known only through fossil records until the Australian species Wollemia nobilis was discovered in 1994 in a temperate rainforest wilderness area of the Wollemi National Park in New South Wales, in a remote series of narrow, steep-sided sandstone gorges 150 km (93 mi) northwest of Sydney. The genus is named after the National Park.[2]

| Wollemia | |

|---|---|

| |

| Young specimen in a botanical garden protected from theft by a steel cage | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Plantae |

| Clade: | Tracheophytes |

| Division: | Pinophyta |

| Class: | Pinopsida |

| Order: | Pinales |

| Family: | Araucariaceae |

| Genus: | Wollemia W.G.Jones, K.D.Hill & J.M.Allen |

| Species: | W. nobilis |

| Binomial name | |

| Wollemia nobilis W.G.Jones, K.D.Hill & J.M.Allen, 1995 | |

In both botanical and popular literature the tree has been almost universally referred to as the Wollemi pine (/ˈwɒləmaɪ/),[3] although it is not a true pine (genus Pinus) nor a member of the pine family (Pinaceae), but, rather, is related to Agathis and Araucaria in the family Araucariaceae.

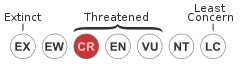

The Wollemi pine is classified as critically endangered (CR) on the IUCN's Red List,[1] and is legally protected in Australia.[4] After it was discovered that the trees could be successfully cloned, new trees were potted up in the Botanic Gardens of Sydney and Mount Annan. A Recovery Plan has been drawn up, outlining strategies for the management of this fragile population; the overall objective is to ensure that this species remains viable in the long term.[4] Wollemi pines have also been presented by Australian prime ministers and foreign affairs ministers to various dignitaries around the world.[5]

Description

Wollemia nobilis is an evergreen tree reaching 25–40 m (82–131 ft) tall. The bark is very distinctive, dark brown, and knobbly, quoted as resembling a popular breakfast cereal.[6] The tree coppices readily, and most specimens are multiple-trunked or appear as clumps of trunks thought to derive from old coppice growth, with some consisting of up to 100 stems of differing sizes.[4] The branching is unusual in that nearly all the side branches never have further branching. After a few years, each branch either terminates in a cone (either male or female) or ceases growth. After this, or when the cone becomes mature, the branch dies. New branches then arise from dormant buds on the main trunk. Rarely, a side branch will turn erect and develop into a secondary trunk, which then bears a new set of side branches.

_seedling.jpg.webp)

The leaves are flat linear, 3–8 cm (1.2–3.1 in) long and 2–5 mm (0.079–0.197 in) broad. They are arranged spirally on the shoot but twisted at the base to appear in two or four flattened ranks. As the leaves mature, they develop from bright lime-green to a more yellowish-green.[7] The seed cones are green, 6–12 cm (2.4–4.7 in) long and 5–10 cm (2.0–3.9 in) in diameter, and mature about 18–20 months after wind pollination. They disintegrate at maturity to release the seeds which are small and brown, thin and papery with a wing around the edge to aid wind-dispersal.[4] The male (pollen) cones are slender conic, 5–11 cm (2.0–4.3 in) long and 1–2 cm (0.39–0.79 in) broad and reddish-brown in colour and are lower on the tree than the seed cones.[4] Seedlings appear to be slow-growing[4] and mature trees are extremely long-lived; some of the older individuals today are estimated to be between 500 and 1,000 years old.[7]

Discovery

The discovery, on or about 10 September 1994, by David Noble, Michael Casteleyn and Tony Zimmerman, only occurred because the group had been systematically exploring the area looking for new canyons.[8] Noble had good botanical knowledge, and quickly recognised the trees as unusual because of the unique bark and worthy of further investigation. He took specimens to work for identification, expecting someone to be able to identify the plants.[9] His specimens were identified by Wyn Jones, a botanist with National Parks and Jan Allen from the Botanical Gardens. After the identification was made, National Parks then went under a veil of secrecy, with the discoverers not learning the full magnitude of their discovery for about six months. National Parks came close to damaging the stand when a helicopter being used to collect cones inadvertently pruned one of the pines with its rotor.[10] The species was subsequently named after Dave. The other members of the discovery party questioned the naming but were informed that nobilis referred to the trees being noble in structure and not to David Noble.[11]

The first illustrations of the Wollemi Pine were done by David Mackay, a botanical artist and scientific illustrator who was working at the Royal Botanic Gardens in Sydney when the species was discovered.[12]

Further study would be needed to establish its relationship to other conifers. The initial suspicion was that it had certain characteristics of the 200-million-year-old family Araucariaceae, but was not similar to any living species in the family. Comparison with living and fossilised Araucariaceae proved that it was a member of that family, and it has been placed into a new genus, beside the genera Agathis and Araucaria.

Fossils closely resembling Wollemia that are thought to be related to it are widespread in Australia, New Zealand and Antarctica from Cretaceous era sediments, but Wollemia nobilis is the sole living member of its genus. These trees remained common throughout eastern Australia until around 40 million years ago but then gradually declined in range and abundance. Before the relict population was discovered in Wollemi National Park, the most recent known fossils of the genus date from approximately 2 million years ago in Tasmania.[13][14] It is thus described as a living fossil or, alternatively, a Lazarus taxon.

Fewer than a hundred trees are known to be growing wild, in three localities not far apart. It is very difficult to count individuals, as most trees are multistemmed and may have a connected root system. Genetic testing has revealed that all the specimens are genetically indistinguishable, suggesting that the species has been through a genetic bottleneck in which its population became so low (possibly just one or two individuals) that all genetic variability was lost.[15]

Threats

In November 2005, wild-growing trees were found to be infected with Phytophthora cinnamomi.[16] New South Wales park rangers believe the virulent water mould was introduced by unauthorised visitors to the site, the location of which is still undisclosed to the public.[16]

The grove of Wollemia trees was endangered by fire during the 2019-20 Australian bushfire season.[17] They were saved by specialist firefighters from the National Parks and Wildlife Service, supported by the Rural Fire Service who installed an irrigation system as well as dropping retardant.[18][19][9][20][21]

Cultivation and uses

A propagation programme made Wollemi pine specimens available to botanical gardens, first in Australia in 2006 and subsequently throughout the world. It may prove to be a valuable tree for ornament, either planted in open ground or for tubs and planters. In Australia, potted native Wollemi pines have been promoted as a Christmas tree.[22] It is also proving to be more adaptable and cold-hardy than its restricted temperate-subtropical, humid distribution would suggest, tolerating temperatures between −5 and 45 °C (23 and 113 °F), with reports, from Japan and the USA, that it can survive down to −12 °C (10 °F). A grove of Wollemi pines planted in Inverewe Garden, Scotland, believed to be the most northerly location of any successful planting, have survived temperatures of −7 °C (19 °F), recorded in January 2010.[23] It also handles both full sun and full shade. Like many other Australian trees, Wollemia is susceptible to the pathogenic water mould Phytophthora cinnamomi, so this may limit its potential as a timber tree.[24] The Royal Botanic Gardens in Sydney have published information on how to grow Wollemi Pines from seed which has been harvested from helicopters from the forest trees. The majority of seeds that fall from the cone are not viable so need to be sorted to retain the plump and dark ones. These can then be sown on top of seed raising mix and watered. Once the water has drained through the mix, the pot should be placed in a plastic bag and refrigerated for two weeks. After this, the pot should be removed from the plastic bag and placed somewhere warm but not very sunny until the seed germinates (remembering to keep them moist but not wet). This could take several months.[25] Examples of the species can be viewed at The Tasmanian Arboretum.

Care

The Wollemi Pine is extremely hardy and versatile in cultivation. Despite it being an endangered species, it is easy to grow and requires relatively low maintenance. It will adapt to a diverse range of climatic zones, thriving in full sun to semi shaded outdoor positions. Can be maintained in a pot almost indefinitely, so makes a good container plants for patios, verandas, and courtyards. Because it tolerates air conditioning, It can be used as an indoor decorative plant. These are basic need to knows for care:

- Watering the Wollemi pine as soon as the growing medium is dry is the best course of action.Do not over or underwater

- Will not survive if held in excessive periods in moist compost.

- If kept indoors, Place in a well lit position one week in every month between May to September.

- Keep out of direct sunlight when indoors.

- Slow release fertilisers, containing low phosphorus content and liquid fertiliser is suggested for optimum growth.

- If in full sunlight, can cause leaves to turn a golden yellow colour.

Pruning

When pruning the Wollemi pine, use sterile secateurs at any time of year to retain its compact form. It can be pruned heavily with up to two thirds of the plant size removed. Pruning heavily can be done on the apical growth and the branches. The best time to prune is during the Winter Months.

Growth Rate

The Wollemi Pine has very controlled growth, especially if it is kept in a pot. It may take up to 25 years to reach 20 feet in height.

Phylogeny

The genus Wollemia shares morphological characteristics with the genera Araucaria and Agathis. Wollemia and Araucaria both have closely crowded sessile and amphistomatic (producing stomata on both sides of the leaf) leaves, and aristate bract scales, while Wollemia and Agathis both have fully fused bracts, ovuliferous scales, and winged seeds.[26] Scrutiny of the fossil record likewise does not clarify Wollemia’s relationship to Araucaria or Agathis, since the former has similarly disparate leaf characters in its adult and juvenile forms, and the latter has similar cone characters.[27] Further, the recent description of several extinct genera within the Araucariaceae points to complex relationships within the family and a significant loss of diversity since the Cretaceous.[28][29] An early study of the rbcL gene sequence places Wollemia in the basal position of the Araucariaceae and as the sister group to Agathis and Araucaria.[30] In contrast, another study of the rbcL sequence shows that Wollemia is the sister group to Agathis, and Araucaria is basal.[31] The different outgroup selection and genes used in previous studies are the reasons behind the discrepancy over the groupings of the three genera.[32] Later genetic studies corroborate Wollemia's placement in the Araucariaceae as sister to Agathis based on data from the 28s rRNA gene,[33] a combination of rbcL and matK genes,[34] and a comprehensive study encompassing nuclear ribosomal 18S and 26S rRNA, chloroplast 16S rRNA, rbcL, matK and rps4, and mitochondrial coxl and atp1 genes.[32]

Fossils indicate that the lineage leading to modern Agathis and Wollemia evolved from the common ancestor with Araucaria in the Early Cretaceous in southern Gondwana[35] within climates experiencing cool moist conditions and a strong photoperiod regime.[36] The most recent common ancestor of Agathis and Wollemia has been proposed to be at least 110 million years old (Early Cretaceous) deduced from the reported oldest fossils of these genera.[35] However, genetic evidence suggests that the divergence of Agathis and Wollemia occurred 61±15 Ma around the beginning of the Cenozoic rather than in the Early Cretaceous.[32] In another recent molecular study, an age of only 18 Ma was inferred for the divergence of Agathis and Wollemia.[37] This also accords with recent revisions of the fossil record in New Zealand that reveal no examples of Agathis or Wollemia-like remains older than the Cenozoic.[38] The relatively minor genetic and morphological diversity in extant species of Agathis compared to the variation in Araucaria is further evidence of the earlier divergence of Araucaria.[39]

Below is the phylogeny of the Araucariaceae based on the consensus from the most recent cladistic analysis of molecular data. It shows the relative positions of Wollemia, Agathis and Araucaria within the division.

| Pinales |

| |||||||||||||||

References

This article incorporates text from the ARKive fact-file "Wollemia" under the Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 3.0 Unported License and the GFDL.

- Thomas, P. (2011). "Wollemia nobilis". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. 2011: e.T34926A9898196. doi:10.2305/IUCN.UK.2011-2.RLTS.T34926A9898196.en.

- "Wollemia nobilis: The Australian Botanic Garden, Mount Annan - April". Royal Botanic Garden, Sydney. Archived from the original on 2015-10-19. Retrieved 2015-10-30.

- "Wollemi pine". ABC Pronounce. Australian Broadcasting Corporation. 19 October 2005. Retrieved 19 July 2020.

- Wollemia nobilis (Wollemi Pine) Recovery Plan (PDF) (Report). NSW Department of Environment and Conservation. Archived from the original on 2018-12-14. Retrieved 2018-12-14. Lay summary.

- Brack, Cris (15 June 2018). "Wollemi pines are dinosaur trees". The Conversation.

- James Woodford, The Wollemi Pine: The incredible discovery of a living fossil from the age of the dinosaurs, (Revised Edition), The Text Publishing Company, 2002, ISBN 1-876485-74-4

- "wollemi pine/facts & figures". Royal Botanic Gardens, Sydney. April 2003. - via ARKive

- Woodford, James (2012-01-30). The Wollemi Pine: The Incredible Discovery of a Living Fossil from the Age of the Dinosaurs. ISBN 9781921834899.

- Wamsley, Laurel (2020-01-16). "Aussie Firefighters Save World's Only Groves Of Prehistoric Wollemi Pines". NPR News. Retrieved 2020-01-17.

- "The Wollemi Pine — a very rare discovery". Royal Botanic Gardens, Sydney. Archived from the original on 2005-03-23. Retrieved 2007-02-08.

- Thornhill, Andrew. "Growing Native Plants: Wollemia nobilis". Australian National Botanic Gardens.

- "David Mackay". New England Focus. 2009-02-08. Retrieved 2017-12-20.

- "Wollemi Pine research — Age & Ancestry". Royal Botanic Gardens, Sydney. Archived from the original on 2005-03-23. Retrieved 2007-03-01.

- James E Eckenwalder. Conifers of the World, The Complete Reference. pp 630-631. Timber Press 2009. ISBN 9780881929744

- Peakall, Rob; Ebert, Daniel; Scott, Leon J.; Meagher, Patricia F.; Offord, Cathy A. (2003). "Comparative genetic study confirms exceptionally low genetic variation in the ancient and endangered relictual conifer, Wollemia nobilis (Araucariaceae)". Molecular Ecology. 12 (9): 2331–2343. doi:10.1046/j.1365-294X.2003.01926.x. PMID 12919472. S2CID 35255532.

- Salleh, Anna (4 November 2005). "Wollemi pine infected by fungus". ABC.

- Hannam, Peter, Incredible, secret firefighting mission saves famous 'dinosaur trees', The Sidney Morning Herald, January 15, 2020

- Hannam, Peter (15 January 2020). "Incredible, secret firefighting mission saves famous 'dinosaur trees'". The Sydney Morning Herald.

- Morton, Adam (15 January 2020). "'Dinosaur trees': firefighters save endangered Wollemi pines from NSW bushfires". The Guardian (Australia edition).

- Mcguirk, Rod (2020-01-16). "Australia firefighters save world's only rare dinosaur trees". San Francisco Chronicle. AP. Retrieved 2020-01-16.

- "Hemmelig aksjon reddet forhistorisk skog fra brannene i Australia" [Secret action saves prehistoric forest from the fires in Australia] (in Norwegian). NTB. 2020-01-16. Retrieved 2020-01-16.

- ACF - Tips for treading lightly this festive season. Australian Conservation Foundation. 2010-12-01. Retrieved 2010-12-19.

- "Jurassic tree survives big chill in trust garden". BBC. 2010-11-01. Retrieved 2010-01-13.

- "Wollemi Pine research — fungal associations & pathogens". Royal Botanic Gardens, Sydney. Archived from the original on 2005-05-01. Retrieved 2007-02-08.

- "How to grow your Wollemi Pine". Royal Botanic Gardens, Sydney. Retrieved 1 May 2016.

- Jones, W.G.; Hill, K.D.; Allen, J.M. (1995). "Wollemia nobilis, a new living Australian genus and species in the Araucariaceae". Telopea. 6 (2–3): 173–6. doi:10.7751/telopea19953014.

- Chambers, T. Carrick; Drinnan, Andrew N.; McLoughlin, Stephen (January 1998). "Some Morphological Features of Wollemi Pine (Wollemia nobilis: Araucariaceae) and Their Comparison to Cretaceous Plant Fossils". International Journal of Plant Sciences. 159 (1): 160–71. doi:10.1086/297534. JSTOR 2474948. S2CID 84425685.

- Cantrill, David J.; Raine, J. Ian (November 2006). "Wairarapaia mildenhallii gen. et sp. nov., a New Araucarian Cone Related to Wollemia from the Cretaceous (Albian‐Cenomanian) of New Zealand". International Journal of Plant Sciences. 167 (6): 1259–69. doi:10.1086/507608. S2CID 85365035.

- Dettmann, Mary E.; Clifford, H. Trevor; Peters, Mark (2012). "Emwadea microcarpa gen. Et sp. Nov.—anatomically preserved araucarian seed cones from the Winton Formation (late Albian), western Queensland, Australia". Alcheringa. 36 (2): 217–37. doi:10.1080/03115518.2012.622155. S2CID 129171237.

- Setoguchi, Hiroaki; Osawa, Takeshi Asakawa; Pintaud, Jean-Christophe; Jaffré, Tanguy; Veillon, Jean-Marie (November 1998). "Phylogenetic relationships within Araucariaceae based on rbcL gene sequences". American Journal of Botany. 85 (11): 1507–16. doi:10.2307/2446478. JSTOR 2446478. PMID 21680310.

- Gilmore, S.; Hill, K. D. (1997). "Relationships of the Wollemi Pine (Wollemia nobilis) and a molecular phylogeny of the Araucariaceae" (PDF). Telopea. 7 (3): 275–91. doi:10.7751/telopea19971020.

- Liu, Nian; Zhu, Yong; Wei, Zongxian; Chen, Jie; Wang, Qingbiao; Jian, Shuguang; Zhou, Dangwei; Shi, Jing; Yang, Yong; Zhong, Yang (2009). "Phylogenetic relationships and divergence times of the family Araucariaceae based on the DNA sequences of eight genes". Chinese Science Bulletin. 54 (15): 2648–55. Bibcode:2009SciBu..54.2648L. doi:10.1007/s11434-009-0373-2.

- Stefanović, Saša; Jager, Muriel; Deutsch, Jean; Broutin, Jean; Masselot, Monique (May 1998). "Phylogenetic relationships of conifers inferred from partial 28S rRNA gene sequences". American Journal of Botany. 85 (5): 688. doi:10.2307/2446539. JSTOR 2446539. PMID 21684951.

- Quinn, C. J.; Price, R. A.; Gadek, P. A. (2002). "Familial Concepts and Relationships in the Conifer Based on rbcL and matK Sequence Comparisons". Kew Bulletin. 57 (3): 513–31. doi:10.2307/4110984. JSTOR 4110984. S2CID 83816639.

- Kunzmann, Lutz (2007). "Araucariaceae (Pinopsida): Aspects in palaeobiogeography and palaeobiodiversity in the Mesozoic". Zoologischer Anzeiger. 246 (4): 257–77. doi:10.1016/j.jcz.2007.08.001.

- McLoughlin, Stephen; Vajda, Vivi (2005). "Ancient Wollemi Pines Resurgent". American Scientist. 93 (6): 540–7. doi:10.1511/2005.6.540.

- Crisp; Cook (2011). "Cenozoic extinctions account for the low diversity of extant gymnosperms compared with angiosperms". New Phytologist. 192 (4): 997–1009. doi:10.1111/j.1469-8137.2011.03862.x. PMID 21895664.

- Pole, Mike (2008). "The record of Araucariaceae macrofossils in New Zealand". Alcheringa. 32 (4): 405–26. doi:10.1080/03115510802417935. S2CID 128903229.

- Kershaw, Peter; Wagstaff, Barbara (2001). "The Southern Conifer Family Araucariaceae: History, Status, and Value for Paleoenvironmental Reconstruction". Annual Review of Ecology and Systematics. 32: 397–414. doi:10.1146/annurev.ecolsys.32.081501.114059. S2CID 86700201.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Wollemia. |

| Wikispecies has information related to Wollemia. |

- Wollemia nobilis media from ARKive

- Conifer Specialist Group (1998). "Wollemia nobilis". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. 1998. Retrieved 11 May 2006.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link) Listed as Critically Endangered (CR D v2.3)

- "The Wollemi Pine — a very rare discovery". Royal Botanic Gardens, Sydney. Archived from the original on 2005-03-23. Retrieved 2007-02-08. (includes facts and figures, ecology, biology)

- Royal Botanic Gardens at Kew's web page about the "Wollemi Pine"

- WollemiPine.com

- Wollemia nobilis at the Gymnosperm Database

- BBC News item 10 May 2005

- BBC News - 'Dinosaur trees' heavily guarded - 02/12/06

- ABC-TV Gardening Fact Sheet

- ABC-TV Science visits Wollemi Pines in the wild 19 May 2005

- Wollemia nobilis (Wollemi Pine) Recovery Plan, January 2007

- Warren, Matthew (16 April 2007). "Biologist takes axe to the 'myth' of Wollemi". The Australian. Retrieved March 4, 2014.

- The Wollemi Pine Transcript of interview on The Science Show (April 2007) with Tim Entwisle, then director of the Royal Botanic Gardens in Sydney.

- Images and information about the Wollemi Pine in Westonbirt Arboretum

- Wollemi Pine available for first time in North America from National Geographic.