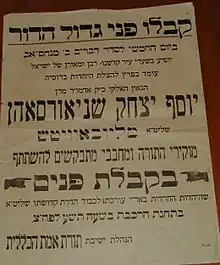

Yosef Yitzchak Schneersohn

Yosef Yitzchak (Joseph Isaac)[1] Schneersohn (Yiddish: יוסף יצחק שניאורסאהן; 21 June 1880 – 28 January 1950) was an Orthodox rabbi and the sixth Rebbe (spiritual leader) of the Chabad Lubavitch chasidic movement. He is also known as the Frierdiker Rebbe (Yiddish for "Previous Rebbe"), the Rebbe RaYYaTz, or the Rebbe Rayatz (an acronym for Rabbi Yosef Yitzchak). After many years of fighting to keep Orthodox Judaism alive from within the Soviet Union, he was forced to leave; he continued to conduct the struggle from Latvia, and then Poland, and eventually the United States, where he spent the last ten years of his life.

Rabbi Yosef Yitzchak Schneersohn | |

|---|---|

Yosef Yitzchak Schneersohn, early 1920s | |

| Title | Lubavitcher Rebbe |

| Personal | |

| Born | 21 June 1880 |

| Died | 28 January 1950 (aged 69) |

| Religion | Judaism |

| Spouse | Nechama Dina Schneersohn |

| Children | Chana Gurary Chaya Mushka Schneerson Shaina Horenstein |

| Parents | Sholom Dovber Schneersohn Shterna Sarah |

| Jewish leader | |

| Predecessor | Sholom Dovber Schneersohn |

| Successor | Menachem Mendel Schneerson |

| Began | 21 March 1920 |

| Ended | 28 January 1950 |

| Buried | 29 January 1950, Queens |

| Dynasty | Chabad Lubavitch |

Early life

Yosef Yitzchak Schneersohn was born in Lyubavichi, Mogilev Governorate, Russian Empire (present-day Smolensk Oblast, Russia), the only son of Rabbi Sholom Dovber Schneersohn (the Rebbe Rashab), the fifth Rebbe of Chabad. He was appointed as his father's personal secretary at the age of fifteen; in that year, he represented his father in the conference of communal leaders in Kovno. The following year (1896), he participated in the Vilna Conference, where Rabbis and community leaders discussed issues such as: genuine Jewish education; permission for Jewish children not to attend public school on Shabbat; the creation of a united Jewish organization for the purpose of strengthening Judaism. He participated in this conference again in 1908.[2]

On 13 Elul 5657 (1897), at the age of seventeen, he married his third cousin, Nechama Dina Schneersohn, daughter of Rabbi Avraham Schneerson of Chișinău, son of Rabbi Yisroel Noach of Nizhyn, son of Rabbi Menachem Mendel Schneersohn, the Tzemach Tzedek.[2]

In 1898, he was appointed head of the Tomchei Temimim yeshiva network.[2]

In 1901,[2] with financial support from Yaakov and Eliezer Poliakoff he opened spinning and weaving mills in Dubrovno and Mahilyow and established a Yeshiva in Bukhara.[3]

As he matured, he campaigned for the rights of Jews by appearing before the Czarist authorities in Saint Petersburg and Moscow. During the Russo-Japanese War of 1904 he sought relief for Jewish conscripts in the Russian army by sending them kosher food and supplies in the Russian Far East.[3]

In 1905, he participated in organizing a fund to provide Passover needs for troops in the Far East.

With rising anti-Semitism and pogroms against Jews, in 1906, he travelled with other prominent rabbis to seek help from Western European governments, especially Germany and the Netherlands, and persuaded bankers there to use their influence to stop pogroms.[2][3]

He was arrested four times between 1902 and 1911 by the Czarist police because of his activism, but was released each time.

Becoming Rebbe

.jpg.webp) |

| Part of a series on |

| Chabad |

|---|

| Rebbes |

|

| Places and landmarks |

| Customs and holidays |

| Organizations |

|

| Schools |

| Chabad philosophy |

| Texts |

| Outreach |

| Terminology |

|

| Chabad offshoots |

Upon the death of his father, Rabbi Sholom Dovber Schneersohn ("Rashab"), in 1920, Yosef Yitzchak became the sixth Rebbe of Chabad-Lubavitch. It was an age of great social and political upheaval following the Russian Revolution of 1917. The victorious anti-religious Bolsheviks were intent on uprooting and suppressing all religious life in the new Bolshevist Russia.

Battling the Bolsheviks

Following the takeover of Russia by the Communists, they created a special "Jewish affairs section" run by Jews known as the Yevsektsiya, which instigated anti-religious activities meant to strip Orthodox Jews of their religious way of life. As Rebbe of a Russia-based Jewish movement, Rabbi Schneersohn was vehemently outspoken against the atheistic Communist regime and its goal of forcibly eradicating religion throughout the land. He purposely directed his followers to set up religious schools, going against the dictates of the Marxist-Leninist "dictatorship of the proletariat".

In 1921, he established a branch of Tomchei Temimim in Warsaw.[2]

In 1924, he was forced by the Cheka (Russian secret police) to leave Rostov due to the Yevsektsiya's slander, and settled in Leningrad.[3] In this time he labored to strengthen Torah observance through activities involving rabbis, Torah schools for children, yeshivot, shochtim, senior Torah-instructors and the opening of mikva'ot; he established a special committee to help manual workers be able to observe Shabbat. He established Agudas Chasidei Chabad in USA and Canada.[2]

In 1927, he established a number of yeshivot in Bukhara.[2]

He was primarily responsible for the maintenance of the now-clandestine Chabad yeshiva system, which had ten branches throughout Russia by this time. He was under continual surveillance by agents of the NKVD.

Imprisonment and release

In 1927, he was arrested and imprisoned in the Bolshoy Dom in Leningrad. He was accused of counter-revolutionary activities, and sentenced to death.[3] A worldwide storm of outrage and pressure from Western governments and the International Red Cross forced the communist regime to commute the death sentence and instead on 3 Tammuz it banished him to Kostroma for an original sentence of three years.[3] Yekaterina Peshkova, a prominent Russian human rights activist, helped from inside as well. This was also commuted following political pressure from the outside, and he was finally allowed to leave Russia for Riga in Latvia, where he lived from 1928 until 1929.

Rabbi Yosef Yitzchak's release from Soviet imprisonment is celebrated each year by the Chabad community.[4]

After his release, Rabbi Yosef Yitzchak then went to the Holy Land where he saw holy gravesites, local yeshivas and Torah centers,[5] and met with rabbis and community leaders from 7–22 August 1929,[6] leaving just prior to the massacre by Arabs of nearly 70 Jews living in Hebron on 24 August.

1929: First visit to the United States

Following his trip to the Holy Land, he turned his attention to the United States, arriving in Manhattan on 17 September 1929 (12 Elul 5689) on the French passenger liner France.[7] Rabbi Schneersohn was greeted by some 600 people, with security provided by over 100 New York City police officers.[8] "May the Almighty bless this great country that has been a refuge for our Jewish people," he said at his arrival.[9] The purpose of his visit was to assess the educational and religious state of American Jewry, and raise awareness of the plight of Soviet Jews.[9] Hailed as "one of the greatest Jews of our age,"[10] he was honored at a 28 October banquet in Manhattan by Orthodox, Conservative and Reform Jewish leaders.[11]

While in the United States, Rabbi Schneersohn also traveled (among places other than New York) to Philadelphia,[12] Baltimore,[13] Detroit,[14] Boston,[15] and Chicago.[16] On 10 July, he met President Herbert Hoover at the White House.[17] As the Republican presidential candidate, Hoover had lobbied for his release.[3] Lubavitch followers in America begged their Rebbe to leave Russia and stay in America, but Rabbi Schneersohn declined, saying that America was an irreligious place where even rabbis shaved off their beards. He left the United States to return to Riga, Latvia, on 17 July 1930.[18]

From 1934 until the early part of World War II, he lived in Warsaw, Poland.

1940: Settling in the United States

Following Nazi Germany's attack against Poland in 1939, Rabbi Schneersohn refused to leave Warsaw. The government of the United States of America, which was still neutral, used its diplomatic relations to convince Nazi Germany to rescue Schneersohn from the war zone in German-occupied Poland.[19] He remained in the city during the bombardments and its capitulation to Nazi Germany. He gave the full support of his organizations to assist as many Jews as possible to flee the invading armies. With the intercession of the United States Department of State in Washington, DC and with the lobbying of many Jewish leaders, such as Jacob Rutstein, on behalf of the Rebbe (and, reputedly, also with the help of Admiral Wilhelm Canaris,[20] the head of the Abwehr), he was finally granted diplomatic immunity and given safe passage to go via Berlin to Riga, Latvia (where the Rebbe was a citizen and which was still free) and then on to New York City, where he arrived on 19 March 1940.[21] Major Ernst Bloch, a decorated German army officer of Jewish descent, was put in command of a group which included Sgt. Klaus Schenk, a "half-Jew" and Pvt. Johannes Hamburger, a "quarter-Jew" assigned to locate the Rebbe in Poland and escort him safely to freedom.[19] They were a few of up to 150,000 Jews and people of Jewish descent who were classified as Mischlinge ("mixed-breeds", i.e., Germans with one or two Jewish grandparents) by the Nazi government, but served in the German armed forces during World War II.[22] They wound up saving not only the Rebbe, but also over a dozen Hasidic Jews in the Rebbe's family or associated with him.[19]

Ironically, without the rescue of Rebbe Schneersohn, the rescue of his son-in-law and the next Rebbe Menachem Mendel Schneerson would not have happened. Working with the government and the contacts Schneersohn had with the US State Department, Chabad was able to save Menachem Mendel from Vichy France in 1941 before the borders were closed down.[23]

When Rabbi Schneersohn came to America (he was the first major Chasidic leader to move permanently to the United States[24]) two of his chassidim came to him, and said not to start up all the activities in which Lubavitch had engaged in Europe, because "America is different." To avoid disappointment, they advised him not even to try. Rabbi Schneersohn wrote, "Out of my eyes came boiling tears", and undeterred, the next day he started the first Lubavitcher Yeshiva in America, declaring that "America is no different."[25] In 1949, Rabbi Schneersohn became a U.S. citizen, with his son-in-law Rabbi Menachem Mendel assisting to coordinate the event. A special dispensation was arranged wherein the federal judge came to "770" to officiate at Rabbi Yosef Yitzchak's citizenship proceedings, rather than the Rebbe travel to a courthouse for the proceedings. Uniquely, the event was recorded on color motion film. In 1950, Schneersohn died in his home in Brooklyn and many members, even the next Rebbe Menachem Mendel Schneerson, declared him the Messiah. This caused a lot of problems for the Chabad community just like it would when Rabbi Menachem Mendel Schneerson died in 1994, and many in the community declared him the Messiah. In 1951, Rabbi Menachem Mendel Schneerson took over the leadership of Chabad and became the next Rebbe of Chabad. When this happened, many stopped declaring Rebbe Schneersohn the Messiah and focused on building out the community under the new Rebbe Schneerson (note: the confusion on names results from the fact that Rebbe Schneerson was the second cousin and son-in-law of Rebbe Schneersohn).[26]

Following the sixth Chabad Rebbe's escape from Nazi occupied Poland and his settlement in New York City, Rabbi Yosef Yitzchok issued a call for repentance, stating L'alter l'tshuva, l'alter l'geula ("speedy repentance brings a speedy redemption"). This campaign was opposed by Rabbis Avraham Kalmanowitz and Aaron Kotler of the Vaad Hatzalah. In return, Rabbi Yosef Yitzchok was critical of the efforts of Rabbis Kalmanowitz and Kotler based on the suspicion that Kalmanowitz and Kotler were discriminating in their use of funds, placing their yeshivas before all else, and that the Mizrachi and Agudas Harabonim withdrew their support of the Vaad after they discovered this fact.[27]

Launch of Lubavitch activities in the United States

During the last decade of Rabbi Schneersohn's life, from 1940 to 1950, he settled in the Crown Heights section of Brooklyn in New York City. Rabbi Schneersohn was already physically weak and ill from his suffering at the hands of the Communists and the Nazis and from multiple health issues including multiple sclerosis,[28] but he had a strong vision of rebuilding Orthodox Judaism in America, and he wanted his movement to spearhead it. In order to do so, he went on a building campaign to establish religious Jewish day schools and yeshivas for boys and girls, women and men. He established printing houses for the voluminous writings and publications of his movement, and started the process of spreading Jewish observance to the Jewish masses worldwide.

He began to teach publicly, and many came to seek out his teachings. He began gathering and sending out a small number of his newly trained rabbis to other cities - a trend later emulated and amplified by his son-in-law and successor, Rabbi Menachem Mendel Schneerson.

In 1948, he established a Lubavitch village in the Land of Israel known as Kfar Chabad near Tel Aviv, on the site of the de-populated Arab village of Al-Safiriyya.[3]

He died in 1950, and was buried at Montefiore Cemetery in Queens, New York City. He had no sons, and his younger son-in-law, Rabbi Menachem Mendel Schneerson ("The Rebbe") succeeded him as Lubavitcher Rebbe, while the older son-in-law, Rabbi Shemaryahu Gurary continued to run the Chabad Yeshiva network Tomchei Temimim.

After Rabbi Schneersohn's passing, his gravesite, known as "the Ohel", became a central point of focus for his successor Rabbi Menachem Mendel Schneerson, who would visit it regularly for many hours of prayer, meditation, and supplication for Jews all over the world.

After his successor's passing and burial next to his father-in-law, philanthropist Joseph Gutnick of Melbourne, Australia, established the Ohel Chabad-Lubavitch Center on Francis Lewis Boulevard in Queens, which is located adjacent to the joint grave site.

Book collection

During his life in Smolensk, Rabbi Schneersohn set up a collection of his family's religious books and writings. It includes texts dating back to the 16th century. After World War I, the Bolsheviks found part of the collection and moved it to the Russian State Library. Another part of the collection was confiscated by Soviet troops in Nazi Germany during World War II and moved to Russia's military archive. In 1994, seven books were loaned to the U.S. Library of Congress for 60 days through an inter-library exchange program.[29]

The books were given to the Chabad-Lubavitch library which helped to prolong the use of the books twice, in 1995 and 1996, before they finally refused to return them to Russia in 2000. They proposed an exchange for the opportunity to keep the books indefinitely, but Russia refused. In 2004, the Chabad-Lubavitch filed a lawsuit against Russia, claiming the remaining books. In 2010, an American court granted their claim, which Russia ignored as invalid. In retaliation, in 2011 Russia put a ban on lending works to American museums. In 2014, Senior United States District Judge Royce C. Lamberth imposed fines of $50,000 a day for Russia refusing to return the Schneersohn collection of more than 12,000 books and 50,000 religious papers. Since Rabbi Schneersohn had no heirs, Russia claims the collection is a national treasure of the Russian people. This dispute is related to the deteriorating ties between Moscow and the U.S. over the ongoing 2014 Russian military intervention in Ukraine.[30] A Russian court ruled that the Library of Congress should pay fines of $50,000 a day for refusing to return the books.[31]

Published works

Hebrew and Yiddish

- Sefer Hamaamarim – 5680–5689, 8 vol.

- Sefer Hamaamarim – 5692–5693.

- Sefer Hamaamarim – 5696–5711, 15 vol.

- Sefer Hamaamarim – Kuntresim, 3 vol.

- Sefer Hamaamarim – Yiddish

- Sefer Hasichot – 5680–5691, 2 vol.

- Sefer Hasichot – 5696–5710, 8 vol.

- Likkutei Dibburim, 4 vol.

- Kuntres Torat Hachasidut

- Kuntres Limud Hachasidut

- Admur Hatzemach Tzedek U'Tenuat Hahaskalah

- Kitzurim L'Biurei Hazohar

- Sefer Hakitzurim – Shaarei Orah

- Kitzurim L'Kuntres Hatefillah

- Sefer Hazichronot, 2 vol.

- Moreh Shiur B'Limudei Yom Yom – Chumash, Tehillim, Tanya

- Seder Haselichot

- Maamar V'Ha'ish Moshe Anav, 5698

- Igrot Kodesh, 14 vol.

- Klalei Chinuch veHaDracha

Hebrew translations

- Likkutei Dibburim, 5 vol.

- Sefer Hasichot – 5700–5705, 3 vol.

- Sefer Hazichronot, 2 vol.

English translations

- Lubavitcher Rabbi's Memoirs

- The Tzemach Tzedek and the Haskala Movement

- On Learning Chasidut

- On the Teachings of Chasidut

- Some Aspects of Chabad Chasidism

- Chasidic Discourses, 2 vol.

- Likkutei Dibburim, 6 vol.

- The Principles of Education and Guidance

- The Heroic Struggle

- The Four Worlds

- Oneness in Creation

CD/video

- America Is No Different

In film

Rabbi Yosef Yitzchak's escape from Poland was the subject of a 2011 Israeli documentary film Ha'rabi Ve'hakatzin Ha'germani (The Chabad Rebbe and the German Officer).[32][33]

See also

References

- His Certificate of Naturalization Archived 7 April 2007 at the Wayback Machine gives his name as Joseph Isaack.

- The Four Worlds, Rabbi Yosef Yitzchak Schneersohn, Kehot, 2006, pp. 87–90. ISBN 0-8266-0462-5

- Encyclopedia of Hasidism, entry: Schneersohn, Joseph Isaac. Naftali Lowenthal. Aronson, London 1996. ISBN 1-56821-123-6

- Schneerson, Menachem M. "Yud-Beis Tammuz 5738." Archived 29 April 2014 at the Wayback Machine Sichos in English: 5738. Volume 1. Vaad Lehafotzas Sichos (Sichos in English). 1978. sichosinenglish.org. Accessed 28 April 2014.

- Der Morgen Journal, 18 September 1929.

- Der Morgen Journal, 18 September 1929.

- Brooklyn Daily Eagle, 17 September 1929, p. 8; Forward, 18 September 1929, pp. 1, 12.

- Brooklyn Daily Eagle, 17 September 1929, p.2.

- Brooklyn Daily Eagle, 18 September 1929, p.18.

- Joint statement of the Union of Orthodox Rabbis of the United States and Canada and of the Rabbinical Board of New York, cited in Brooklyn Daily Eagle, 18 September 1929, p. 18.

- Jewish Daily Bulletin, 28 October 1929, p. 3.

- Jewish Exponent, 20 December 1929; Philadelphia City News, 27 Dec. 1929.

- Baltimore Sun, 13 January 1930.

- Detroit Jewish News, 18 April 1930, p. 6.

- Jewish Daily Bulletin, 15 June 1930, p. 2.

- The Sentinel (Chicago), 14 Feb. 1930, p.[5].

- The Sentinel (Chicago), 25 July 1930, p. 11.

- Jewish Daily Bulletin, 18 July 1930, p. 4.

- Rigg, Bryan Mark, Rescued from the Reich: How One of Hitler's Soldiers Saved the Lubavitcher Rebbe (Yale University Press 2006)

- Altein, R, Zaklikofsky, E, Jacobson, I: "Out of the Inferno: The Efforts That Led to the Rescue of Rabbi Yosef Yitzchak Schneersohn of Lubavitch from War Torn Europe in 1939–40", p. 160. Merkos L'Inyonei Chinuch, 2002 ISBN 0-8266-0683-0

- See video Archived 4 December 2008 at the Wayback Machine.

- Rigg, Bryan Mark, Hitler's Jewish Soldiers: The Untold Story of Nazi Racial Laws and Men of Jewish Descent in the German Military (University Press of Kansas ed. 2009)

- Friedman, Menachem, and Heilman, Samuel, The Rebbe: The Life and Afterlife of Menachem Mendel Schneerson, Princeton, 2010; Bryan Mark Rigg, The Rabbi Saved by Hitler's Soldiers, Kansas, 2016.

- "Schneerson, Yoseph Yitzchak", in Moshe D. Sherman, Orthodox Judaism in America: A Biographical Dictionary and Sourcebook (Westport, CN: Greenwood Press, 1996), p. 189.

- See video Archived 7 December 2008 at the Wayback Machine.

- The Previous Rebbe Accepts US Citizenship - Program One Hundred Twenty Eight - Living Torah. Chabad.org. 1949-03-17; "Out of the Inferno," Reviewed by Efraim Zuroff, The Jerusalem Post, 15 December 2002; Bryan Mark Rigg, The Rabbi Saved by Hitler's Soldiers, Kansas, 2016.

- Rigg, Bryan Mark. Rescued from the Reich. Cambridge University Press. 2005.

- </https://www.chabad.org/therebbe/article_cdo/aid/1104700/jewish/I-Have-Come-to-My-Garden.htm>

- "Russian court demands U.S. Library of Congress hand over Jewish texts". Reuters. 23 May 2014. Retrieved 23 May 2014.

- "Russia Warns of Retaliation Over U.S. Ruling on a Jewish Collection". The New York Times. 17 January 2013. Retrieved 17 January 2013.

- "Russia Court Demands 7 Hasidic Trove Books Back – Sets 50K-a-Day Fine". The Jewish Daily Forward. 22 May 2014. Retrieved 22 May 2014.

- The Chabad Rebbe and the German Officer. IsraelFilmCenter.org. Accessed 16 January 2014. Archived 5 January 2014 at the Wayback Machine

- The Chabad Rebbe and the German Officer. JMTFilms.com. Accessed 16 January 2014.

External links

- Biography

- The "Ohel" – Gravesite

- Yud Shvat

- Books in English

- Memoirs

- Video of Schneersohn arriving in America

- Family Tree

- Some of his published works in Hebrew

- Who Was Rabbi Yosef Yitzchak Schneerson? by Dr. Henry Abramson

| Religious titles | ||

|---|---|---|

| Preceded by Sholom Dovber Schneersohn |

Rebbe of Lubavitch 1920–1950 |

Succeeded by Menachem Mendel Schneerson |

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Notes:

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

References:

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||