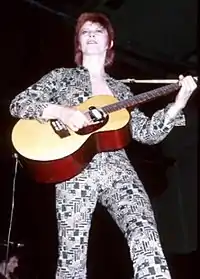

Ziggy Stardust (character)

Ziggy Stardust is a fictional character created by English musician David Bowie, and was Bowie's alter ego during 1972 and 1973. The eponymous character of the song "Ziggy Stardust" and its parent album The Rise and Fall of Ziggy Stardust and the Spiders from Mars (1972), Ziggy Stardust was retained for Bowie's subsequent concert tour through the United Kingdom, Japan and North America, during which Bowie performed as the character backed by his band The Spiders from Mars. Bowie continued the character in his next album Aladdin Sane (1973), which he described as "Ziggy goes to America". Bowie retired the character on 3 July 1973 at a concert at the Hammersmith Odeon in London, which was filmed and released on the documentary Ziggy Stardust and the Spiders from Mars.

| Ziggy Stardust | |

|---|---|

| |

| First appearance | 1972 |

| Last appearance | 3 July 1973 |

| Created by | David Bowie |

| Portrayed by | David Bowie |

| In-universe information | |

| Full name | Ziggy Stardust |

| Species | Human |

| Gender | Male |

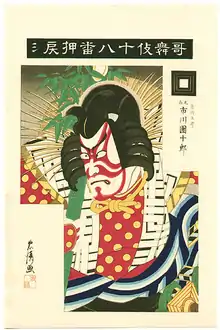

As conveyed in the title song and album, Ziggy Stardust is an androgynous rock star who came before an impending apocalyptic disaster. After accumulating a large following of fans and being worshipped as a messiah, Ziggy eventually dies as a victim of his own fame and excess. The character was meant to symbolise an over-the-top, sexually liberated rock star as a comment of the society in which celebrities are worshipped. Influences for the character were English singer Vince Taylor, Texan musician the Legendary Stardust Cowboy, Japanese kabuki theatre, and Japanese fashion designer Kansai Yamamoto, who designed many of Bowie's costumes as Ziggy Stardust.

Ziggy Stardust's exuberant fashion made the character and Bowie himself staples in the glam rock repertoire well into the 1970s, defining what the genre would become. The success of the character and its iconic look flung Bowie into international superstardom.

Ziggy Stardust's look and message of youth liberation are now representative of one of Bowie’s most memorable eras. The Rise and Fall of Ziggy Stardust and the Spiders from Mars became Bowie’s second most popular album in terms of record sales.[1]

Appearance

.jpg.webp)

Hair

As Ziggy Stardust, Bowie had a bright red mullet.[3] The hairstyle was inspired by that of a model for Japanese designer Kansai Yamamoto that Bowie had seen in Honey magazine,[4] and modelled on three different images from Vogue — a French issue inspired the front of the haircut, while the sides and back came from two different German copies.[5] Bowie's mullet was cut and dyed, using peroxide and German hair dye to achieve the orange-red colour, by hairdresser Suzi Fussey,[6][7] who accompanied the Ziggy Stardust tour until 1973.[8] The haircut achieved widespread mainstream success in popular fashion, as Bowie himself stated in 1993, "[The Ziggy cut] became to hairdressing in the early seventies, what the Lady Di cut was for the early eighties. Only with double the appeal, because it worked for both sexes."[9]

Clothing

Long and slender, Ziggy was dressed in glamorous outfits often with flared legs and shoulders, and an open chest.[3]

On the cover of The Rise and Fall of Ziggy Stardust and the Spiders from Mars, Bowie appeared a green suit of his own design, made by his tailor friend Freddie Burretti and local seamstress Sue Frost. Produced in a geometric-patterned fabric, the bomber jacket and matching cuffed trousers were worn with knee-high, lace-up boots designed by Stan Miller. Similar outfits were made for Bowie's backing band The Spiders From Mars;[4] these costumes worn in early live performances were based on those sported by the Droogs in Stanley Kubrick's film A Clockwork Orange. Bowie explained, "I wanted to take the hardness and violence of those Clockwork Orange outfits — the trousers tucked into big boots and the codpiece things — and soften them up by using the most ridiculous fabrics. It was a Dada thing — this extreme ultraviolence in Liberty fabrics." In addition to his green suit, Bowie's costumes for early concerts were white satin trousers with a flock-patterned jacket, and a multi-coloured jumpsuit that he also wore on Top of the Pops.[10]

By August 1972, Bowie was introducing Kansai Yamamoto's designs as stage wear for the Ziggy character.[4] In total, seven costumes were designed for Ziggy Stardust by Yamamoto,[11] some of which Yamamoto had originally designed for women, in the kabuki tradition.[12] The collection Yamamoto provided Bowie in April 1973 included a white robe with "David Bowie" written in Japanese, a silver leotard hung with a floor-length fringe of glass beads, a striped spandex bodystocking, and a multi-coloured kimono that could be torn away to reveal a red loincloth.[13]

Makeup

The character had pale skin, described by Bowie as a “snow-white tan”.[14] Following the instruction Yamamoto gave to his models,[4] Bowie shaved off his eyebrows in late 1972, adding to Ziggy's alien visage.[15] On Ziggy's forehead was a gold "astral sphere" suggested by make-up artist Pierre La Roche (who also applied the lightning flash to Bowie's face for the cover of Aladdin Sane).[5] When the Ziggy Stardust tour came to Japan in April 1973, Bowie met the kabuki theatre star Bando Tamasaburo, who taught him about traditional Japanese makeup techniques.[13] In a 1973 Mirabelle magazine article, La Roche explained that Bowie bought most of his make-up from a shop in Rome but acquired his "white rice powder" from "Tokyo's Woolworth's equivalent". Bowie used a "German gold base in cake form" for the sphere, and would occasionally "outline that gold circle with tiny gold rhinestones, stuck on with eyelash glue".[5]

By the end of the Ziggy Stardust period in 1973, Bowie would spend at least two hours before each concert to have his makeup done.[5] According to La Roche, for his last few English concerts, Bowie painted tiny lightning streaks on his cheek and upper leg.[16]

Origins

The character was inspired by English rock 'n' roll singer Vince Taylor, whom Bowie met after Taylor had a breakdown and believed himself to be a cross between a god and an alien.[17][18] Bowie's lyrical allusions to Taylor include identifying Ziggy as a "leper messiah".[19] Taylor was only part of the character's blueprint.[20] In the 1960s Bowie had seen Gene Vincent performing live wearing a leg-brace after a car accident, and observed: “It meant that to crouch at the mike, as was his habit, [Vincent] had to shove his injured leg out behind him to, what I thought, great theatrical effect. This rock stance became position number one for the embryonic Ziggy.”[21][22]

Bowie biographers also propose that Bowie developed the concept of Ziggy as a melding of the persona of Iggy Pop with the music of Lou Reed during a visit to the US in 1971.[23][24] A girlfriend recalled his "scrawling notes on a cocktail napkin about a crazy rock star named Iggy or Ziggy", and on his return to England he declared his intention to create a character "who looks like he's landed from Mars".[25]

Bowie later asserted that Ziggy Stardust was born out of a desire to move away from the denim and hippies of the 1960s.[26] Along these lines, some critics assert that Bowie's artificial concoction of a rock star persona was a symbolic critique of the artificiality seen in the rock world of the time.[27] Bowie had previously created artificial stage personas in 1970 with his backing band Hype. Over a small series of shows which, while poorly received at the time, are now credited as the origin of glam rock,[28] the band performed in flamboyant costumes, each with an accompanying persona of a spoof superhero. Bowie, dressed in a blue cape, lurex tights, thigh boots and a leotard with colourful scarves sewn onto his shirt, was "Rainbowman".[28][29] Describing his costume as "very spacey", he later explained that his idea for the outfits was to counter the popular image of rock acts at the time, which was "all jeans and long hair".[29] The concept behind Rainbowman was recycled and reinvented as Ziggy Stardust.[30]

Name

Bowie told Rolling Stone that the name "Ziggy" was "one of the few Christian names [he] could find beginning with the letter 'Z'".[31] He later explained in a 1990 interview for Q magazine that the Ziggy part came from a tailor's shop called Ziggy's that he passed on a train, and he liked it because it had "that Iggy [Pop] connotation but it was a tailor's shop, and I thought, Well, this whole thing is gonna be about clothes, so it was my own little joke calling him Ziggy. So Ziggy Stardust was a real compilation of things."[32][33] "Stardust" came from the Legendary Stardust Cowboy, the stage name of singer Norman Carl Odam,[32][34] whose music intrigued Bowie.[35][36]

Fictional narrative

Much of the Ziggy Stardust story was created by Bowie and told in the album The Rise and Fall of Ziggy Stardust and the Spiders from Mars, or appears in Bowie’s writings as plans for a never-realised theatrical performance of the narrative. The character of Ziggy Stardust is conceived to have been an androgynous, bisexual alien rock star from an unspecified planet, who was sent to earth to deliver the message that Earth had five years left, due to a lack of natural resources. Meanwhile, children around the world have become obsessed with rock ‘n’ roll music, and came to look to the rock star Ziggy Stardust as a prophet.[37]

Ziggy gathered a large following, as adults are too preoccupied with the minutiae of their own lives to pay attention to their children. The children become obsessed with Ziggy’s hedonistic way of life. As the end nears, Stardust prophesies of the “Starman” waiting in the sky, who will come to save the earth. At the end of it all, Ziggy is torn apart on stage by black holes. This was reflective of Bowie’s paranoia that he would be killed on stage during a performance in real life, especially after his announcement that he was gay (a claim that he would later rescind). The character shows Bowie’s paranoia, and the difficulties of living as a larger than life celebrity.[37]

The character was revisited by Bowie in his next album Aladdin Sane (1973), which topped the UK chart, and was his first number-one album. Described by Bowie as "Ziggy goes to America", it contained songs he wrote while travelling to and across the US during the earlier part of the Ziggy Stardust Tour.[38][39]

Cultural impact

– David Bowie, in an interview with Rolling Stone

The character received success around the world. By the time Bowie returned to Britain for the final leg of the Ziggy Stardust tour in May 1973 following the release of Aladdin Sane, he had become the biggest English rock star since The Beatles almost a decade earlier,[41] in terms of concert and record sales.[42][43] Rolling Stone described Ziggy Stardust as the ultimate rock star: "He’s a wild, hedonistic figure ... but at his core communicates peace and love".[44]

The character influenced the glam rock genre and fashion wave.[45] Bowie as Ziggy Stardust became one of the most iconic images of rock history. According to The Washington Post, "He was not only glam's principal architect, he was its most beautiful specimen."[46]

Retirement

By July 1973, Bowie had been touring as Ziggy for eighteen months.[13] Due to the intense nature of his touring life, Bowie felt as though maintaining the Ziggy persona was affecting his own personality and sanity too much; acting the same role over an extended period, it became difficult for him to separate Ziggy Stardust from his own character offstage.[lower-alpha 1] Bowie was also beginning to reach a point of creative boredom and felt that he could no longer perform Ziggy with the same enthusiasm.[lower-alpha 2] There were also practical reasons behind his decision to retire the character: Bowie's record company RCA refused to finance a third large US tour due to Bowie's management overspending in excess of $300,000 during the 1972 and 1973 tours, as well as disappointing record sales in the US.[13]

Bowie retired Ziggy Stardust during a live concert on 3 July 1973, at London’s Hammersmith Odeon in front of 3,500 fans. The concert featured an 18-song set, with Jeff Beck joining the band for a medley of "The Jean Genie" and The Beatles' "Love Me Do".[51] Just before the final song of the concert, "Rock 'n' Roll Suicide",[52] Bowie announced, “Of all the shows on this tour, this particular show will remain with us the longest, because not only is it the last show of the tour, but it's the last show that we'll ever do”. The fans and press took this to mean that Bowie was retiring entirely causing much media attention, however it only referred to the Ziggy Stardust persona, and the Spiders from Mars backing band.[51][53]

The final Ziggy concert was filmed by D. A. Pennebaker and released in 1979 as the documentary Ziggy Stardust and the Spiders from Mars[52] and the audio on the live album Ziggy Stardust: The Motion Picture (released in 1983).[54]

Legacy

Ziggy Stardust is widely considered Bowie's greatest creation.[46][55]

In 2012, a plaque was unveiled by the Crown Estate at the site at which the iconic Ziggy Stardust album cover photograph was taken by Brian Ward on Heddon Street, London.[56] The unveiling was attended by original Spiders from Mars band members Woody Woodmansey and Trevor Bolder, and was unveiled by Gary Kemp.[57] The plaque was the first to be installed by the Crown Estate and is one of the few plaques in the country devoted to fictional characters.[56]

In 2015, the African butterfly species Bicyclus sigiussidorum was named after the character due to its "glammy" appearance.[58] (Sigiussidorum is a Latin rendering of "Ziggy Stardust".)[59]

In popular culture

- Music

- The 1976 cyberpunk rock opera Starmania features a character called Ziggy.

- The British rock band Def Leppard referenced the character in their song Rocket on their 1987 album Hysteria.

- The Swedish band Gyllene Tider recorded a song called "Åh Ziggy Stardust (var blev du av?)" ("Ah Ziggy Stardust, what became of you?"),[60] included on the 1990 re-release of their album Gyllene Tider.

- Ziggy Stardust was one of several pop icons Marc Almond dressed up as in the video for his 1995 single "Adored and Explored" and the cover of its follow-up single, "The Idol".[60]

- The Omēga character, featured on the cover of Marilyn Manson's 1998 album Mechanical Animals was based on Ziggy Stardust, aesthetically and story-wise.[61]

- A cartoon version of Ziggy featured in the video for Boy George's 2008 single "Yes We Can".[60]

- Matt Sorum made reference to the character in the song "What Ziggy Says" on his 2014 album Stratosphere.[60]

- Film and television

- Fictional pop star Brian Slade and his space-age alter ego Maxwell Demon in the 1998 film Velvet Goldmine were based on Bowie in his Ziggy Stardust period,[62] though Bowie would dissociate himself from the film.[63]

- In the 1999 comedy special Golden Years, Ricky Gervais plays a Bowie impersonator named Clive Meadows who arrives at a business meeting as Ziggy Stardust.[64]

- In the sixth episode of the 2007 sitcom Flight of the Conchords, the character Brett (Bret McKenzie) is visited by a dream version of Ziggy Stardust, among several other of Bowie's personas.[65]

See also

Notes

- Bowie: "It was quite easy to become obsessed night and day with the character. I became Ziggy Stardust. David Bowie went totally out the window. Everybody was convincing me that I was a messiah ... I got hopelessly lost in the fantasy."[47] "My whole personality was affected ... I thought I might as well take Ziggy to interviews as well. Why leave him on stage? Looking back it was very absurd. It became very dangerous. I really did have doubts about my sanity." [48][49]

- Bowie: "I had an awful lot of fun doing [Ziggy] ... but my performance on stage reached a peak. I felt I couldn't go on stage in the same context again ... if I'm tired with what I'm doing wouldn't it be long before the audience realised."[50]

References

- Dee, Johnny (7 January 2012). "David Bowie: Infomania". The Guardian. Archived from the original on 8 January 2014. Retrieved 3 February 2020.

- Thian, Helene M. (2013). "For David Bowie, Japanese style was more than just fashion". The Japan Times. The Japan Times, Ltd. Retrieved 29 May 2020.

- Zanetta & Edwards (1986), p. 112

- Gorman, Paul (4 August 2015). "David Bowie: his style story, 1972-1973". The Guardian. Retrieved 8 September 2020.

- Harris (2010), pp. 194-195

- Alexander, Ella (7 January 2016). "David Bowie Style File". British Vogue. Retrieved 8 September 2020.

- Peters, Alex (8 January 2019). "Unpacking David Bowie's Beauty Evolution". Dazed. Retrieved 8 September 2020.

- Zara, Christopher (17 January 2016). "The Story Behind David Bowie's Ziggy Stardust Haircut, A Radical Red Revolution". International Business Times. Retrieved 8 September 2020.

- "The Ziggy Stardust Haircut". The Ziggy Stardust Companion. 2018. Retrieved 29 May 2020.

- Pegg (2016), "The Ziggy Stardust Tour (UK)" in chapt. Live

- Dellas, Mary (2018). "Dressing David Bowie As 'Ziggy Stardust'". The Cut. Vox Media, Inc. Retrieved 29 May 2020.

- Panisch, Alex (2016). "5 Things We Learned From Kansai Yamamoto, David Bowie's Costume Designer". Out. Pride Media. Retrieved 29 May 2020.

- Pegg (2016), "The 1973 Ziggy Stardust Tour (aka The Aladdin Sane Tour)" in chapt. Live

- Ziggy Stardust (1972), song lyrics. Retrieved from "Ziggy Stardust". Genius. Retrieved 29 May 2020.

- Pegg (2016), "The Ziggy Stardust Tour (US)" in chapt. Live

- Archived from "David Bowie, Ziggy Stardust Style". The Blitz Kids. 2009. Retrieved 29 May 2020.

- "BBC – BBC Radio 4 Programmes – Ziggy Stardust Came from Isleworth". BBC. Archived from the original on 30 September 2010. Retrieved 5 November 2010.

- "The Leper Messiah: Vince Taylor". David Bowie Official. Archived from the original on 27 July 2011. Retrieved 5 November 2010.

- Pegg (2016), p. 573

- Mahoney, Elisabeth (20 August 2010). "Ziggy Stardust Came from Isleworth – review". The Guardian. London. Archived from the original on 16 January 2014. Retrieved 5 November 2010.

- Pegg (2016), "Hang On To Yourself" in chapt. The Songs From A to Z.

- "Vincent, Gene | Encyclopedia.com". www.encyclopedia.com. Retrieved 2020-10-29.

- Sandford (1997), pp. 73–74

- Pegg (2016), p. 619

- Sandford 1997, pp. 73–74.

- "David Bowie On The Ziggy Stardust Years: 'We Were Creating The 21st Century In 1971'". NPR. 19 September 2003. Archived from the original on 20 July 2017. Retrieved 21 May 2018.

- McLeod, Ken. "Space Oddities: Aliens, Futurism and Meaning in Popular Music". Popular Music. Vol. 22. JSTOR 3877579.

- Hughes, Rob (20 December 2014). "David Bowie: The Gig That Invented Glam". Louder Sound. Retrieved 5 September 2020.

- Chapman (2020), p. 129

- Chapman (2020), p. 179

- "11–14". The Observer. 20 June 2004. Archived from the original on 21 September 2017. Retrieved 20 September 2017.

- Campbell (2005), p. 294

- Du Noyer, Paul (25 August 2009). "David Bowie interview by Paul Du Noyer 1990". Paul Du Noyer. Archived from the original on 15 July 2011. Retrieved 26 April 2011.

- Kot, Greg (12 January 2016). "Space oddities: David Bowie's hidden influences". BBC. Retrieved 6 September 2020.

- Buckley (2005), pp. 110-111

- Philo (2018), p. 59

- Archived from "Frequently Armed Questions". The Ziggy Stardust Companion. 2007. Retrieved 29 May 2009.

- Buckley (2005), p. 157

- Sandford (1997), pp. 108

- "500 Greatest Songs of All Time". Rolling Stone. 7 April 2011. Archived from the original on 11 August 2019. Retrieved 28 March 2020.

- James Hale (director) (2012). David Bowie and the Story of Ziggy Stardust (Documentary). BBC.

- Zanetta & Edwards (1986), p. 208

- Hendler (2020), pp. 11-12

- Light, Alan (2016). "'Ziggy Stardust': How Bowie Created the Alter Ego That Changed Rock". Rolling Stone. Rolling Stone Magazine. Retrieved 29 May 2020.

- Bowie (1980), p. 31

- Harrington, Richard (9 June 2009). "30 Years On, 'Ziggy Stardust' Rises Again". The Washington Post. Retrieved 10 September 2020.

- Greene, Andy (2016). "David Bowie: 7 Wild Quotes From the 'Station to Station' Era". Rolling Stone. Retrieved 29 May 2020.

- Jones, Allan (29 October 1977). "Goodbye To Ziggy And All That". Melody Maker. Retrieved 13 September 2020 – via Bowie Golden Years.

- Jones (2012), p. 171

- Miles (1980), p. 54

- Gallucci, Michael (2016). "When David Bowie Abruptly Retired Ziggy Stardust". Ultimate Classic Rock. Townsquare Media, Inc. Retrieved 29 May 2020.

- James, David E. (13 February 2016). "The many deaths of David Bowie". OUPBlog. Oxford University Press. Retrieved 13 September 2020.

- Greene, Andy (22 November 2012). "Flashback: Ziggy Stardust Commits 'Rock and Roll Suicide' at Final Gig". Rolling Stone. Retrieved 14 September 2020.

- Pegg (2016), "Ziggy Stardust: The Motion Picture" in chapt. The Albums.

- "David Bowie". Ultimate Classic Rock. Retrieved 10 September 2020.

- Sillito, David (2012). "Site of Ziggy Stardust album cover shoot marked with plaque". BBC News Online. Retrieved 29 May 2020.

- Press Association (27 March 2012). "David Bowie's Ziggy Stardust album marked with blue plaque". The Guardian. Archived from the original on 22 September 2017. Retrieved 18 September 2017.

- Brattström, Oskar; Aduse-Poku, Kwaku; Collins, Steve C.; Di Micco De Santo, Teresa; Brakefield, Paul M. (2016). "Revision of theBicyclus sciathisspecies group (Lepidoptera: Nymphalidae) with descriptions of four new species and corrected distributional records". Systematic Entomology. 41 (1): 207–228. doi:10.1111/syen.12150. ISSN 0307-6970. PMC 4810357.

- Pegg (2016), "And Many Other Last Names" in chapt. Aprocrypha and Miscellany.

- Pegg (2016), "Don't Think You Knew You Were In This Song" in chapt. Aprocrypha and Miscellany.

- Wiederhorn, John (2018). "'Mechanical Animals': 10 Things You Didn't Know Marilyn [sic] Manson's Great Glam Album". Revolver Mag. Project M Group LLC. Retrieved 29 May 2020.

- Harrington, Richard (6 November 1998). "Gone Glam Digging". Washington Post. Archived from the original on 9 September 2020. Retrieved 9 September 2020.

- Pegg (2016), "Watch That Man" in chapt. Aprocrypha and Miscellany.

- Ess, Ramsey (29 May 2019). "Before The Office, There Was Golden Years". Vulture. Retrieved 9 September 2020.

- Cobb, Kayla (11 January 2016). "'Flight Of The Conchords' Gave One Of The Greatest Celebrations Of David Bowie's Life". Decider. Retrieved 9 September 2020.

- Sources

- Bowie, David (1980). Bowie In His Own Words. Compiled by Barry Miles. London: Omnibus Press. ISBN 0860016455.

- Buckley, David (2005) [First published 1999]. Strange Fascination – David Bowie: The Definitive Story. London: Virgin Books. ISBN 978-0-7535-1002-5.

- Campbell, Michael (2005). Popular music in America: The Beat Goes On. Wadsworth/Thomson Learning. ISBN 0-534-55534-9.

- Chapman, Ian (2020). David Bowie FAQ: All That's Left to Know About Rock's Finest Actor. Rowman & Littlefield. ISBN 1493051407.

- Harris, John (2010). Hail! Hail! Rock 'n' Roll: The Ultimate Guide to the Music, the Myths and the Madness. Hachette UK. ISBN 0748114866.

- Hendler, Glenn (2020). David Bowie's Diamond Dogs. New York: Bloomsbury. ISBN 1501336592.

- Jones, Dylan (2012). When Ziggy Played Guitar: David Bowie, The Man Who Changed The World. Random House. ISBN 1409052133.

- Miles, Barry (1980). David Bowie Black Book. London, New York: Omnibus Press. ISBN 0860018083.

- Pegg, Nicholas (2016). The Complete David Bowie (7th ed.). London: Titan Books. ISBN 978-1-78565-365-0.

- Philo, Simon (2018). Glam Rock: Music in Sound and Vision. Rowman & Littlefield. ISBN 1442271485.

- Sandford, Christopher (1997) [1996]. Bowie: Loving the Alien. London: Da Capo Press. ISBN 0-306-80854-4.

- Sims, Josh (1999). Rock Fashion. Omnibus Press. ISBN 071197733X.

- Zanetta, Tony; Edwards, Henry (1986). Stardust: The David Bowie Story. London: Michael Joseph. ISBN 0718125959.