1889–1890 pandemic

The 1889–1890 flu pandemic, also known as the "Asiatic flu"[1] or "Russian flu", was a pandemic that killed about 1 million people worldwide,[2][3] out of a population of about 1.5 billion. It was the last great pandemic of the 19th century, and is among the deadliest pandemics in history.[4][5]

| 1889-1890 flu pandemic | |

|---|---|

The 12 January 1890, edition of the Paris satirical magazine Le Grelot depicted an unfortunate influenza sufferer bowled along by a parade of doctors, druggists, skeleton musicians and dancing girls representing quinine and antipyrine | |

| Disease | Influenza or coronavirus disease (uncertain) |

| Virus strain | A/H3N8, A/H2N2, or coronavirus OC43 (uncertain) |

| Location | Worldwide |

| First outbreak | Bukhara, Russian Empire |

| Date | 1889 – 1890 |

| Suspected cases‡ | 300-900 million (estimate) |

Deaths | 1 million (estimate) |

| ‡Suspected cases have not been confirmed by laboratory tests as being due to this strain, although some other strains may have been ruled out. | |

The most reported effects of the pandemic took place from October 1889 to December 1890, with recurrences in March to June 1891, November 1891 to June 1892, winter of 1893–1894, and early 1895. It is not known for certain what agent was responsible for the pandemic. Since the 1950s, it has been conjectured to be Influenza A virus subtype H2N2.[6][7][8]

A 1999 seroarcheological study found the strain to be Influenza A virus subtype H3N8.[9] A 2005 genomic virological study says that "it is tempting to speculate" that the virus might not have been an influenza virus, but human coronavirus OC43.[7] In 2020, Danish researchers reached a similar conclusion in a study which had not been published in a peer-reviewed academic journal as of November 2020. They described the symptoms as very like those of COVID-19.[10]

Outbreak and spread

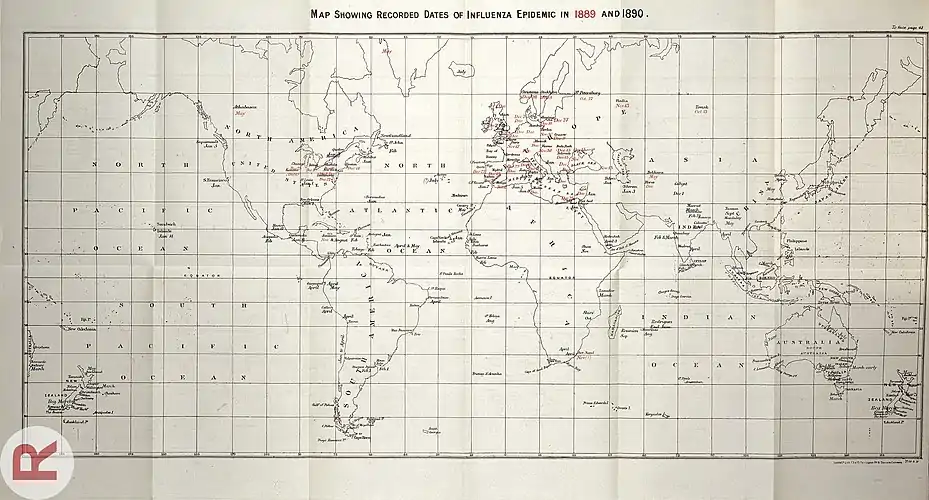

Modern transport infrastructure assisted the spread of the 1889 influenza. The 19 largest European countries, including the Russian Empire, had 202,887 km of railroads, and transatlantic travel by sea took less than six days (not significantly different than current travel time by air, given the timescale of the global spread of a pandemic).[9] It was the first pandemic to spread not just through a region such as Eurasia, but worldwide.[11]

The flu was first reported in the Central Asian city of Bukhara in the Russian Empire, in May 1889.[1][12][11] The Trans-Caspian railway enabled it to spread farther into Samarkand by August, and Tomsk, 3,200 km away, by October.[11] Since the Trans-Siberian Railway had not yet been constructed, spread to the east was slower, but it reached the westernmost station of the Trans-Caspian, Krasnovodsk (now known as Türkmenbaşy), and from there the Volga trade routes which carried it by November to Saint Petersburg (infecting 180,000 of the city's under one million inhabitants) and Moscow.[11][13] By mid-November Kiev was infected, and the next month the Lake Baikal region was as well, followed by the rest of Siberia and Sakhalin by the end of the year.[11]

From St. Petersburg, the infection spread via the Baltic shipping trade to Vaxholm in early November 1889, and then to Stockholm and the rest of Sweden, infecting 60% of the population within eight weeks.[11] First Norway, and then Denmark, followed soon after.[11] The German Empire first received it in Poznań in December, and on 12 November 600 workers were reported sick in Berlin and Spandau, with the cases in the city reaching 150,000 within a few days, and ultimately half of its 1.5 million inhabitants.[11] Vienna was also infected around the same time.[11] Rome was reached by 17 December.[11] The flu also arrived in Paris that month, and towards its end had spread to Grenoble, Toulon, Toulouse, Lyon, and Ajaccio.[11] At this point Spain was also infected, killing up to 300 a day in Madrid.[11] It reached London at the same time, from where it then spread quickly to Birmingham, Glasgow, Edinburgh, and Dublin.[11]

The first case on American soil was reported on 18 December 1889.[11] It then quickly spread throughout the East Coast and all the way to Chicago and Kansas in days.[11] The first death, Thomas Smith of Canton, Massachusetts, was reported on 25 December.[11] San Francisco and other cities were also reached before the month was over, with the total US death toll at about 13,000.[11] From there it spread south to Mexico and farther down, reaching Buenos Aires by 2 February.[11]

Durban in South Africa was reached in November 1889, while India received it in February 1890, and Singapore and Indonesia did by March.[11] These were followed by Japan, Australia, and New Zealand by April, and then China in May; the infection continued to spread, reaching its original starting point in Central Asia.[11]

In four months it had spread throughout the Northern Hemisphere. Deaths peaked in Saint Petersburg on 1 December 1889, and in the United States during the week of 12 January 1890. The median time between the first reported case and peak mortality was five weeks.[9] In Malta, the Asiatic flu took hold between January 1889 and March 1890, with a fatality rate of 4% (39 deaths), and a resurgence in January to May 1892 with 66 fatalities (3.3% case fatality).[14] When this flu began, whether it was contagious was debated, but its quick action and pervasiveness across all climates and terrains proved that it was.[12]

Responses

Medical treatment

There was no standard treatment of the flu; quinine and phenazone were used, as well as small doses of strychnine and larger ones of whiskey and brandy, and as cheaper treatments linseed, salt and warm water, and glycerin.[11] Many people also thought that fasting would 'starve' the fever, based on the belief that the body would not produce as much heat with less food; this was in fact poor medical advice.[11] Furthermore, many doctors still believed in the miasma theory of disease rather than infectious spread;[11] for example, notable professors of the University of Vienna, Hermann Nothnagel and Otto Kahler considered that the disease was not contagious.[11]

Public health

A result of the Asiatic flu in Malta is that influenza became for the first time a compulsorily notifiable illness.[16]

Identification of virus subtype responsible

Influenza virus

Researchers have tried for many years to identify the subtypes of Influenza A responsible for the 1889–1890, 1898–1900 and 1918 epidemics. Initially, this work was primarily based on "seroarcheology"—the detection of antibodies to influenza infection in the sera of elderly people—and it was thought that the 1889–1890 pandemic was caused by Influenza A subtype H2, the 1898–1900 epidemic by subtype H3, and the 1918 pandemic by subtype H1.[17] With the confirmation of H1N1 as the cause of the 1918 flu pandemic following identification of H1N1 antibodies in exhumed corpses,[17] reanalysis of seroarcheological data suggested Influenza A subtype H3 (possibly the H3N8 subtype) as a more likely cause for the 1889–1890 pandemic.[9][17]

Coronavirus

After the 2002–2004 SARS outbreak, virologists started sequencing and comparing human and animal coronaviruses, and comparison of two virus strains in the Betacoronavirus 1 species, bovine coronavirus and human coronavirus OC43, indicated that they had a most recent common ancestor in the late 19th century, with several methods yielding most probable dates around 1890.[7][18] Authors speculated that an introduction of the former strain to the human population might have caused the epidemic.[7] In 2020, Danish researchers Lone Simonsen and Anders Gorm Pedersen similarly calculated that the human coronavirus OC43 had split from bovine coronavirus about 130 years before, approximately coinciding with the pandemic in 1889–1890. The calculation was based on genetic comparisons between bovine coronavirus and different strains of OC43. Their research had not been formally published as of November 2020.[10]

Pathology

Patterns of mortality

The young, the old, and those with underlying conditions were most at risk, and usually died of pneumonia or heart attack caused by physical stress.[11] Unlike most influenza pandemics such as the 1918 flu, primarily elderly people died in 1889.[10] Due to generally lower standards of living, worse hygiene, and poorer standard of medicine, the proportion of vulnerable people was higher than in the modern world.[11]

Notable infections

First outbreak

- 1 January 1890 Henry R. Pierson

- 7 January 1890 Augusta of Saxe-Weimar-Eisenach

- 14 January 1890 Ignaz von Döllinger

- 15 January 1890 Walker Blaine

- 18 January, Amadeo I of Spain

- 22 January 1890 Adam Forepaugh

- 22 February 1890 Bill Blair

- 12 March 1890 William Allen

- 26 March 1890 Afrikan Spir

- 23 May 1890 Louis Artan

- 19 July 1890 James P. Walker

- 14 August 1890 Michael J. McGivney

Recurrences

- 23 January 1891 Prince Baudouin of Belgium[lower-alpha 1]

- 10 February 1891 Sofya Kovalevskaya

- 18 March 1891 William Herndon

- 8 May 1891 Helena Blavatsky

- 15 May 1891 Edwin Long

- 3 June 1891 Oliver St John

- 9 June 1891 Henry Gawen Sutton

- 1 July 1891 Frederic Edward Manby

- 20 December 1891 Grisell Baillie

- 28 December 1891 William Arthur White

- 8 January 1892 John Tay

- 10 January 1892 John George Knight

- 12 January 1892 Jean Louis Armand de Quatrefages de Bréau

- 14 January 1892 Prince Albert Victor, Duke of Clarence and Avondale, grandson of Queen Victoria

- 17 January 1892 Charles A. Spring

- 20 January 1892 Douglas Hamilton

- 12 February 1892 Thomas Sterry Hunt

- 15 April 1892 Amelia Edwards

- 5 May 1892 Gustavus Cheyney Doane

- 24 May 1892 Charles Arthur Broadwater

- 10 June 1892 Charles Fenerty

- 21 April 1893 Edward Stanley, 15th Earl of Derby

- 7 August 1893 Thomas Burges

- 31 August 1893 William Cusins

- 15 December 1893 Samuel Laycock

- 16 December 1893 Tom Edwards-Moss

- 3 January 1894 Hungerford Crewe, 3rd Baron Crewe

- 24 January 1894 Constance Fenimore Woolson[lower-alpha 2]

- 14 March 1894 John T. Ford

- 19 June 1894 William Mycroft

- 19 February 1895 John Hulke

- 1 March 1895 Frederic Chapman

- 2 March 1895 Berthe Morisot

- 5 March 1895 Sir Henry Rawlinson, 1st Baronet

- 20 March 1895 James Sime

- 24 March 1895 John L. O'Sullivan

- 2 August 1895 Joseph Thomson

See also

- Carlill v Carbolic Smoke Ball Company – Case in English contract law, concerning an advertisement of 1891 for a putative flu remedy

- Spanish flu

- Asian flu

- Hong Kong flu

- 1977 Russian flu

- 2009 swine flu pandemic

- Coronavirus: COVID-19 pandemic

Notes

- Baudouin's death was officially attributed to influenza, although many rumors attributed it to other causes.

- Woolson fell from the window of her room while likely under the influence of laudanum, which she may have been taking to relieve symptoms of influenza.

References

- Ryan, Jeffrey R., ed. (2008). "Chapter 1 - Past Pandemics and Their Outcome". Pandemic Influenza: Emergency Planning and Community Preparedness. CRC Press. p. 16. ISBN 978-1-42006088-1.

The Asiatic Flu of 1889-1890 was first reported in Bukhara, Russia

- Shally-Jensen, Michael, ed. (2010). "Influenza". Encyclopedia of Contemporary American Social Issues. 2. ABC-CLIO. p. 1510. ISBN 978-0-31339205-4.

The Asiatic flu killed roughly one million individuals

- Williams, Michelle Harris; Preas, Michael Anne (2015). "Influenza and Pneumonia Basics Facts and Fiction" (PDF). Maryland Department of Health - Developmental Disabilities Administration. University of Maryland. Pandemics. Archived from the original (PDF) on 12 December 2017. Retrieved 25 March 2020.

Asiatic Flu 1889-1890 1 million

- Garmaroudi, Farshid S. (30 October 2007). "The Last Great Uncontrolled Plague of Mankind". Science Creative Quarterly. Retrieved 25 March 2020.

The Asiatic flu, 1889-1890: It was the last great pandemic of the nineteenth century.

- "History's deadliest pandemics, from ancient Rome to modern America". Washington Post. Retrieved 2 January 2021.

- Hilleman, Maurice R. (19 August 2002). "Realities and enigmas of human viral influenza: pathogenesis, epidemiology and control". Vaccine. Elsevier. 20 (25–26): 3068–3087. doi:10.1016/S0264-410X(02)00254-2. PMID 12163258.

- Vijgen, Leen; Keyaerts, Els; Moës, Elien; Thoelen, Inge; Wollants, Elke; Lemey, Philippe; Vandamme, Anne-Mieke; Van Ranst, Marc (2005). "Complete Genomic Sequence of Human Coronavirus OC43: Molecular Clock Analysis Suggests a Relatively Recent Zoonotic Coronavirus Transmission Event". Journal of Virology. 79 (3): 1595–1604. doi:10.1128/JVI.79.3.1595-1604.2005. PMC 544107. PMID 15650185.

- Madrigal, Alexis (26 April 2010). "1889 Pandemic Didn't Need Planes to Circle Globe in 4 Months". Wired Science. Archived from the original on 29 April 2010.

- Valleron, Alain-Jacques; Cori, Anne; Valtat, Sophie; Meurisse, Sofia; Carrat, Fabrice; Boëlle, Pierre-Yves (11 May 2010). "Transmissibility and geographic spread of the 1889 influenza pandemic". PNAS. 107 (19): 8778–8781. Bibcode:2010PNAS..107.8778V. doi:10.1073/pnas.1000886107. PMC 2889325. PMID 20421481.

- Knudsen, Jeppe Kyhne (13 August 2020). "Overraskende opdagelse: Coronavirus har tidligere lagt verden ned" [Surprising discovery: Coronavirus has previously brought down the world]. DR (in Danish). Retrieved 13 August 2020.

A presumed influenza pandemic in 1889 was actually caused by coronavirus, Danish research shows.

- The 1889-1890 Flu Pandemic: The History of the 19th Century’s Last Major Global Outbreak (Kindle ed.). Charles River Editors.

- Mouritz, A. (1921). The Flu. Retrieved 5 April 2020.

- "The 1889 Russian Flu In The News". Circulating Now from the N.I.H. National Institutes of Health. 13 August 2014. Archived from the original on 3 February 2020. Retrieved 25 March 2020.

In November 1889, a rash of cases of influenza-like-illness appeared in St. Petersburg, Russia. Soon, the "Russia Influenza" spread

- Savona-Ventura, Charles (2005). "Past Influenza pandemics and their effect in Malta". Malta Medical Journal. 17 (3): 16–19. Retrieved 25 March 2020.

1889-90 pandemic – The Asiatic Flu [...] by the end of March 1890. The case fatality rate approximated 4.0% [Table 1]. A resurgence of the infection became apparent in January–May 1892 with a total of 2017 reported cases and 66 deaths [case fatality rate 3.3%]

- Parsons, Henry Franklin (1891). Report on the Influenza Epidemic of 1889–90. Local Government Board.

- Cilia, Rebekah (15 March 2020). "How Malta dealt with past influenza pandemics, with today's being 'inevitable'". The Malta Independent.

Compulsory notification of infectious disease [...] Influenza was made a notifiable infection on the 20th January 1890 with the appearance of 1889-90, Asiatic Flu

- Dowdle, W. R. (1999). "Influenza A virus recycling revisited". Bulletin of the World Health Organization. Geneva: World Health Organization. 77 (10): 820–828. PMC 2557748. PMID 10593030.

- Vijgen, Leen; Keyaerts, Els; Lemey, Philippe; Maes, Piet; Van Reeth, Kristien; Nauwynck, Hans; Pensaert, Maurice; Van Ranst, Marc (2006). "Evolutionary History of the Closely Related Group 2 Coronaviruses: Porcine Hemagglutinating Encephalomyelitis Virus, Bovine Coronavirus, and Human Coronavirus OC43". Journal of Virology. 80 (14): 7270–7274. doi:10.1128/JVI.02675-05. PMC 1489060. PMID 16809333.

Further reading

- Bäumler, Christian (1890). Ueber die Influenza von 1889 und 1890 [On the influenza of 1889 and 1890)] (in German).

- Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). . Encyclopædia Britannica. 14 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. pp. 552–556.

- Parsons, Henry Franklin; Klein, Edward Emmanuel (1893). Further Report and Papers on Epidemic Influenza, 1889–92. Local Government Board.

- Ziegler, Michelle (3 January 2011). "Epidemiology of the Russian flu, 1889–1890". Contagions: Thoughts on Historic Infectious Disease. Archived from the original on 22 June 2013.