1928 Atlantic hurricane season

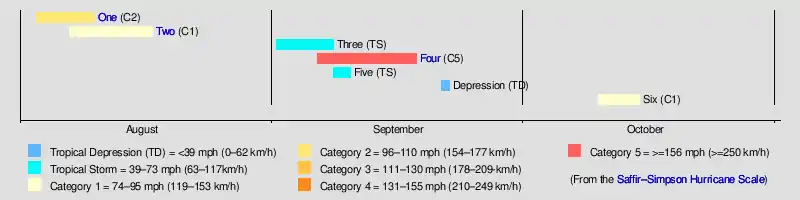

The 1928 Atlantic hurricane season featured the Okeechobee hurricane, which was second deadliest tropical cyclone in the history of the United States. Only seven tropical cyclones developed during the season. Of these seven tropical systems, six of them intensified into a tropical storm and four further strengthened into hurricanes. One hurricane deepened into a major hurricane, which is Category 3 or higher on the modern-day Saffir–Simpson hurricane wind scale.[1] The first system, the Fort Pierce hurricane, developed near the Lesser Antilles on August 3. The storm crossed the Bahamas and made landfall in Florida. Two fatalities and approximately $235,000 in damage was reported.[nb 1] A few days after the first storm developed, the Haiti hurricane, formed near the southern Windward Islands on August 7. The storm went on to strike Haiti, Cuba, and Florida. This storm left about $2 million in damage and at least 210 deaths. Impacts from the third system are unknown.

| 1928 Atlantic hurricane season | |

|---|---|

Season summary map | |

| Seasonal boundaries | |

| First system formed | August 3, 1928 |

| Last system dissipated | October 15, 1928 |

| Strongest storm | |

| Name | "Okeechobee" |

| • Maximum winds | 160 mph (260 km/h) (1-minute sustained) |

| • Lowest pressure | 929 mbar (hPa; 27.43 inHg) |

| Seasonal statistics | |

| Total depressions | 7 |

| Total storms | 6 |

| Hurricanes | 4 |

| Major hurricanes (Cat. 3+) | 1 |

| Total fatalities | >4,289 |

| Total damage | > $102 million (1928 USD) |

| Related article | |

The most significant storm of the season was Hurricane Four, nicknamed the Okeechobee hurricane. Becoming a Category 5 hurricane, the hurricane struck Puerto Rico at that intensity. Several islands of the Greater and Lesser Antilles suffered "great destruction", especially Guadeloupe and Puerto Rico. The storm then crossed the Bahamas as a Category 4 hurricane, leaving deaths and severe damage on some islands. Also as a Category 4, the cyclone struck West Palm Beach, Florida, resulting in catastrophic wind damage. Inland flooding and storm surge resulted in Lake Okeechobee overflowing its banks, flooding nearby towns and leaving at least 2,500 deaths, making it the second deadliest hurricane in the United States after the 1900 Galveston hurricane. Overall, this storm caused at least $100 million in damage and 4,079 deaths. The three remaining systems did not impact land. Collectively, the storms of this season left over $102 million in damage and at least 4,289 fatalities.

The season's activity was reflected with an accumulated cyclone energy (ACE) rating of 83.[1] ACE is, broadly speaking, a measure of the power of the hurricane multiplied by the length of time it existed, so storms that last a long time, as well as particularly strong hurricanes, have high ACEs. It is only calculated for full advisories on tropical systems at or exceeding 39 mph (63 km/h), which is tropical storm strength.[2]

Timeline

Systems

Hurricane One

| Category 2 hurricane (SSHWS) | |

| |

| Duration | August 3 – August 10 |

|---|---|

| Peak intensity | 105 mph (165 km/h) (1-min) 971 mbar (hPa) |

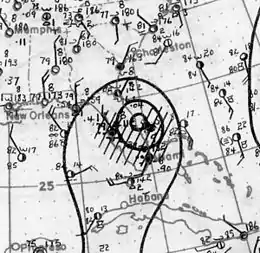

This storm developed from a tropical wave north of the Virgin Islands on August 3.[3] The system paralleled the Greater Antilles throughout much of its early existence. On August 6, the tropical storm strengthened to the equivalent of a Category 1 hurricane while positioned over the Bahamas. The hurricane continued to intensify, and after reaching Category 2 hurricane strength, peaked with sustained winds of 105 mph (165 km/h) on August 7. Shortly thereafter, the hurricane made landfall as a slightly weaker storm near Fort Pierce, Florida, at 07:00 UTC on August 8. Weakening as it moved across Florida over the course of the next day, the storm briefly moved over the Gulf of Mexico before recurving northwards. It made a second landfall on the Florida Panhandle on August 10 as a tropical storm. Once inland, the system continued to weaken, degenerating to tropical depression strength before transitioning into an extratropical storm later that day. The extratropical remnants progressed outwards into the Atlantic Ocean before dissipating on August 14.[4]

In its early developmental stages north of the Greater Antilles, the storm disrupted shipping routes through the Bahamas and generated rough seas offshore Cuba.[5][6] At its first landfall on Fort Pierce, the hurricane caused property damage in several areas, particularly in coastal regions, where numerous homes were unroofed.[7] Central Florida's citrus crop was hampered by the strong winds and heavy rain.[3] Several of Florida's lakes, including Lake Okeechobee, rose past their banks, inundating coastal areas.[8][9] Damage to infrastructure was less in inland regions than at the coast, though power outages caused a widespread loss of communication.[10] At the hurricane's second landfall, wind damage was relatively minor, though torrential rainfall, aided by orthographic lift, caused extensive flooding as far north as the Mid-Atlantic states.[11] Overall, the hurricane caused $235,000 in damages, primarily in Florida, and two deaths.[3]

Hurricane Two

| Category 1 hurricane (SSHWS) | |

| |

| Duration | August 7 – August 17 |

|---|---|

| Peak intensity | 90 mph (150 km/h) (1-min) ≤998 mbar (hPa) |

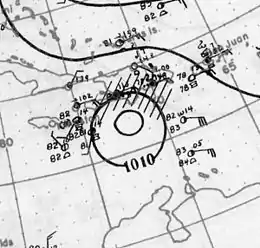

A tropical wave developed into a tropical depression near Tobago on August 7.[3] The system then passed through the Windward Islands just south of Carriacou and Petite Martinique. Upon entering the Caribbean Sea early on August 8, the tropical depression strengthened into a tropical storm. On August 9, the storm strengthened to the equivalent of a Category 1 hurricane, while positioned south of Dominican Republic. The next day, the hurricane peaked with winds of 90 mph (150 km/h). After striking the Tiburon Peninsula of Haiti, the cyclone began weakening and fell to tropical storm intensity on August 12. By midday on the following day, the storm made landfall near Cienfuegos, Cuba. Upon emerging into the Straits of Florida, the storm began to re-strengthen. Early on August 13, it struck Big Pine Key, Florida, as a strong tropical storm. Weakening slowly while moving north-northwestward, the system made another landfall near St. George Island. After moving inland, the tropical storm slowly deteriorated, falling to tropical depression intensity on August 15 and dissipating over West Virginia on August 17.[4]

In Haiti, the storm completely wiped out livestock and many crops, particularly coffee, cocoa, and sugar.[12] Several villages were also destroyed, rendering approximately 10,000 people homeless. The damage totaled $1 million and at least 200 deaths were reported.[13] The only impact in Cuba was downed banana trees.[3] In Florida, the storm left minor wind damage along the coast. A Seaboard Air Line Railroad station was destroyed in Boca Grande, while signs, trees, and telephone poles were knocked down in Sarasota. Several streets in St. Petersburg were closed due to flooding or debris.[14] Between Cedar Key and the Florida Panhandle, several vessels capsized. Water washed up along the side of roads and in wooded areas.[15] The storm contributed to flooding onset by the previous hurricane, with rainfall peaking at 13.5 in (340 mm) in Caesars Head, South Carolina.[16] The worst impact from flooding occurred in North Carolina, where several houses were demolished. Six people were killed in the state, of which four due to flooding. Property damage in the state totaled over $1 million.[17] Overall, the storm caused at least $2 million in damage and 210 fatalities.[13][17]

Tropical Storm Three

| Tropical storm (SSHWS) | |

| |

| Duration | September 1 – September 8 |

|---|---|

| Peak intensity | 60 mph (95 km/h) (1-min) |

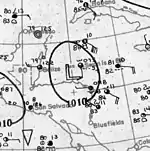

A tropical storm formed on September 1 just south of Hispaniola. Moving just north of due west, the system brushed the south coast of Jamaica as a 40 mph (65 km/h) tropical storm on September 2 before slowly beginning to intensify on September 3. The strengthening tropical storm reached its peak of 60 mph (95 km/h) on September 4 shortly before making landfall on the Yucatan Peninsula near Playa del Carmen near its peak intensity early on September 5. The system deteriorated after crossing the peninsula and entering the Bay of Campeche early on September 6 as a weak tropical storm. Later, the storm restrengthened slightly to winds of 50 mph (80 km/h) while nearing mainland Mexico on September 7. The tropical storm then weakened slightly shortly before making landfall north of Tampico early on September 8 as a weak 40 mph (65 km/h) tropical storm. After moving inland, the system weakened quickly to a depression and dissipated.[4] The storm brought 2.18 in (55 mm) of rain to Brownsville, Texas.[18]

Hurricane Four

| Category 5 hurricane (SSHWS) | |

| |

| Duration | September 6 – September 18 |

|---|---|

| Peak intensity | 160 mph (260 km/h) (1-min) ≤929 mbar (hPa) |

The Great Okeechobee Hurricane of 1928 or The Great Bahamas Hurricane of 1928 or Hurricane San Felipe II of 1928

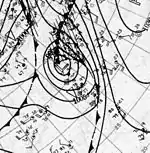

This system developed as a tropical depression just offshore the west coast of Africa on September 6. The depression strengthened into a tropical storm later that day, shortly before passing south of the Cape Verde Islands. Further intensification was slow and halted by late on September 7. However, about 48 hours later, the storm resumed strengthening and became a Category 1 hurricane on the modern-day Saffir–Simpson hurricane wind scale. Still moving westward, the system reached Category 4 intensity before striking Guadeloupe on September 12.[4] There, the storm brought 1,200 deaths and extensive damage, including the destruction of approximately 85%–95% of banana crops, the severe damage dealt to 70%–80% of tree crops, and the roughly 40% of the sugar cane crops ruined.[3][19] Martinique,[20] Montserrat,[21] and Nevis also reported damage and fatalities,[22] but the impacts at those locations were not nearly as severe as in Guadeloupe.[3]

Around midday on September 13, the storm strengthened into a Category 5 hurricane, based on the anemometer at San Juan observing sustained winds of 160 mph (268 km/h). The hurricane peaked with sustained winds at the intensity. About six hours later, the system made landfall in Puerto Rico; it was the only recorded tropical cyclone to strike the island as a Category 5.[4] Very strong winds resulted in severe damage in Puerto Rico. Throughout the island, 24,728 homes were destroyed and 192,444 were damaged, leaving over 500,000 people homeless. Heavy rainfall also led to extreme damage to vegetation and agriculture. On Puerto Rico alone, there were 312 deaths and about $50 million in damage.[23] After emerging into the Atlantic, the storm weakened slightly, falling to Category 4 intensity. It began crossing through the Bahamas on September 16.[4] Many buildings and houses were damaged or destroyed, especially on Bimini, Eleuthera, New Providence, and San Salvador Island. Nineteen deaths were reported, eighteen from a sloop disappearing and one due to drowning.[21]

Early on September 17, the storm made landfall near West Palm Beach, Florida, with winds of 145 mph (233 km/h).[4] In the city, more than 1,711 homes were destroyed. Elsewhere in Palm Beach County, impact was severest around Lake Okeechobee. The storm surge caused water to pour out of the southern edge of the lake, flooding hundreds of square miles as high as 20 feet (6.1 m) above ground. Numerous houses and buildings were swept away in the cities of Belle Glade, Canal Point, Chosen, Pahokee, and South Bay. At least 2,500 people drowned, while damage was estimated at $25 million.[24] While crossing Florida, the system weakened significantly, falling to Category 1 intensity late on September 17. It curved north-northeastward and briefly re-emerged into the Atlantic on September 18, but soon made another landfall near Edisto Island, South Carolina, with winds of 85 mph (140 km/h). Early on the following day, the system weakened to a tropical storm and became extratropical over North Carolina hours later.[4] Overall, the system caused $100 million in damage and at least 4,079 deaths.[3][20][21][22][23][24]

Tropical Storm Five

| Tropical storm (SSHWS) | |

| |

| Duration | September 8 – September 10 |

|---|---|

| Peak intensity | 70 mph (110 km/h) (1-min) ≤1015 mbar (hPa) |

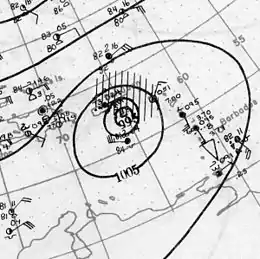

A tropical storm developed about 835 mi (1,345 km) northeast of Barbados on September 8. The storm moved rapidly north-northwestward and slowly strengthened. Upon turning northward on September 10,[4] the system attained its peak intensity as a strong tropical storm with maximum sustained winds of 70 mph (110 km/h) and a high minimum barometric pressure of 1,015 mbar (30.0 inHg), both of which were measured by ships.[3] Shortly thereafter, it began losing tropical characteristics and transitioned into an extratropical cyclone later that day while located about 700 mi (1,100 km) south-southeast of Cape Race, Newfoundland and Labrador.[4] The extratropical remnants continued to move rapidly northeastward until being absorbed by an extratropical low pressure.[3]

Tropical Depression

A low pressure area previously associated with a frontal system developed into a tropical depression near Bermuda on September 22. The depression had sustained winds of 30 mph (45 km/h) and failed to strengthen further. It became extratropical on September 23.[3]

Hurricane Six

| Category 1 hurricane (SSHWS) | |

| |

| Duration | October 10 – October 15 |

|---|---|

| Peak intensity | 90 mph (150 km/h) (1-min) ≤980 mbar (hPa) |

The final cyclone of the season developed about 740 mi (1,190 km) west-northwest of the easternmost islands of Cape Verde on October 10. Moving north-northwest, the system maintained intensity on October 11, before beginning to intensify more rapidly on October 12. Early the next day, it strengthened into a Category 1 hurricane and peaked with maximum sustained winds of 90 mph (150 km/h). After turning northeastward, the hurricane weakened to a tropical storm on October 14. Around 06:00 UTC on October 15, the cyclone transitioned into an extratropical cyclone while situated approximately 285 mi (460 km) northwest of Flores Island in the Azores.[4]

Further reading

- Monge, Luigi (2007). "Their Eyes Were Watching God: African-American Topical Songs on the 1928 Florida Hurricanes and Floods". Popular Music. 26 (1): 129–140. doi:10.1017/S0261143007001171.

Notes

- All damage figures are in 1928 United States dollars, unless otherwise noted

References

- Atlantic basin Comparison of Original and Revised HURDAT. Hurricane Research Division; Atlantic Oceanographic and Meteorological Laboratory (Report). Miami, Florida: National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. February 2014. Retrieved July 4, 2014.

- David Levinson (August 20, 2008). 2005 Atlantic Ocean Tropical Cyclones. National Climatic Data Center (Report). Asheville, North Carolina: National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Retrieved July 1, 2013.

- Christopher W. Landsea; et al. (December 2012). Documentation of Atlantic Tropical Cyclones Changes in HURDAT. Atlantic Oceanographic and Meteorological Laboratory (Report). Miami, Florida: National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Retrieved June 6, 2015.

- "Atlantic hurricane best track (HURDAT version 2)" (Database). United States National Hurricane Center. May 25, 2020.

- "Storm Curves Away; Florida to Miss Blow". Sarasota Herald-Tribune. Miami, Florida. Associated Press. August 6, 1928. p. 1. Retrieved March 21, 2013.

- "Heavy Sea on Cuban Coast". The Evening Independent. Havana, Cuba. Associated Press. August 8, 1928. p. 12. Retrieved March 22, 2013.

- "Tampa Isolated by Florida Storm". Painesville Telegraph. Jacksonville, Florida. Associated Press. August 9, 1928. p. 1. Retrieved March 23, 2013.

- "Hurricane Sweeps to Gulf". Rochester Evening Journal and the Post Express. Jacksonville, Florida. Associated Press. August 9, 1928. p. 2. Retrieved March 22, 2013.

- "Florida in Grip of Gale". Lewiston Evening Journal. Melbourne, Florida. Associated Press. August 8, 1928. p. 9. Retrieved March 22, 2013.

- "Roofs Off at Kissimmee". The Evening Independent. Tampa, Florida. Associated Press. August 9, 1928. p. 1. Retrieved March 23, 2013.

- R. W. Schoner; S. Molansky. "Rainfall Associated With Hurricanes (And Other Tropical Disturbances)" (PDF). United States Weather Bureau's National Hurricane Research Project. p. 84. Retrieved March 21, 2013.

- "Haiti Hurricane". The Observer. New York. September 8, 1928. p. 56. Retrieved September 4, 2015.

- "Haiti Hurricane Leaves Death, Chaos In Wake". Chicago Tribune. Port-au-Prince, Haiti. Associated Press. August 19, 1928. p. 3. Retrieved September 4, 2015.

- "Pass-a-Grille Warned Against High Tides Today Following Tropical Gale Which Swept Entire West Coast but Caused Little Damage". St. Petersburg Times. August 14, 1928. pp. 1–2. Retrieved September 4, 2015.

- "Boats Wrecked, Hodges Reports". St. Petersburg Times. Tallahassee, Florida. Associated Press. August 16, 1928. p. 2. Retrieved September 4, 2015.

- United States Army Corps of Engineers (1945). Storm Total Rainfall In The United States. War Department. p. SA 2–13.

- "Ten Die in Tropical Storm that Hits Southern States". Huntingdon Daily News. August 17, 1928.

- "Tropical Storm Passed Inland on Coast of Mexico". Corsicana Daily Sun. Brownsville, Texas. September 8, 1928. p. 1.

- Don R. Hoy (1961). Agricultural Land Use of Guadeloupe, Issue 12. Washington, D.C.: National Academies Press. p. 64. Retrieved March 15, 2014.

- Edward N. Rappaport; Jose Fernandez-Partagas; Jack Beven (1995–1997). The Deadliest Atlantic Tropical Cyclones, 1492–1996. National Hurricane Center (Report). National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration.

- Wayne Neely (2014). The Great Okeechobee Hurricane of 1928. Bloomington, Indiana: iUniverse. ISBN 978-1-4917-5446-7. Retrieved May 7, 2015.

- Vincent K. Hubbard (2002). Swords, Ships & Sugar: History of Nevis. Corvallis, Oregon: Premiere Editions International.

- Frank Mújica-Baker. Huracanes y Tormentas que han afectado a Puerto Rico (PDF) (in Spanish). Estado Libre Asociado de Puerto Rico, Agencia Estatal para el manejo de Emergencias y Administración de Desastres. pp. 4, 9, 10. Archived from the original (PDF) on October 1, 2015. Retrieved September 5, 2015.

- Memorial Web Page for the 1928 Okeechobee hurricane. National Weather Service Miami, Florida (Report). Miami, Florida: National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. June 29, 2009. Retrieved September 4, 2015.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to 1928 Atlantic hurricane season. |