2018 Italian general election

The 2018 Italian general election was held on 4 March 2018 after the Italian Parliament was dissolved by President Sergio Mattarella on 28 December 2017.[7]

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

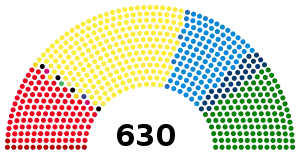

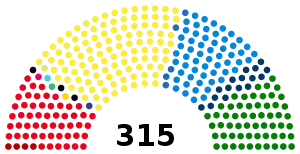

All 630 seats in the Chamber of Deputies 315 seats in the Senate | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

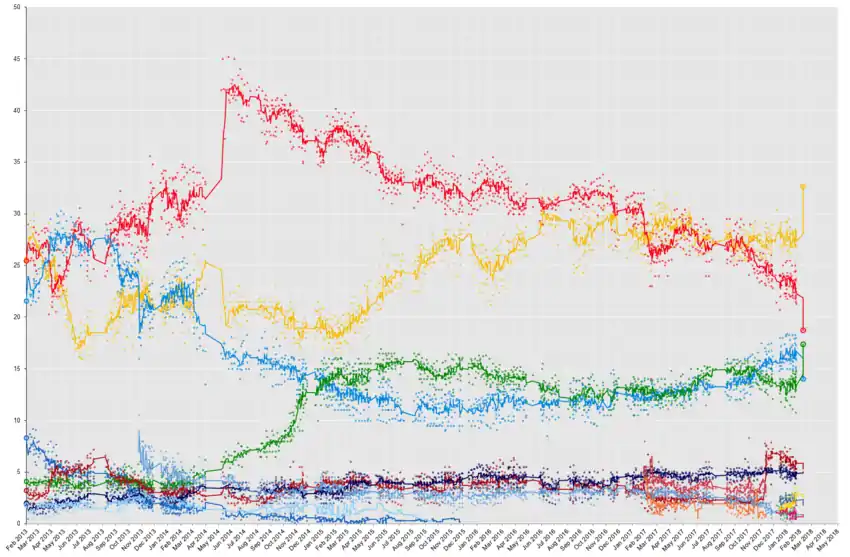

| Opinion polls | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Turnout | 72.93%[1] | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

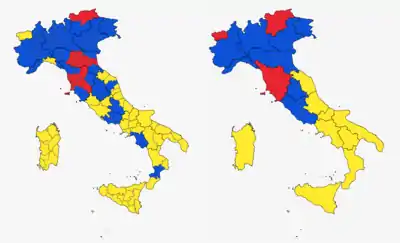

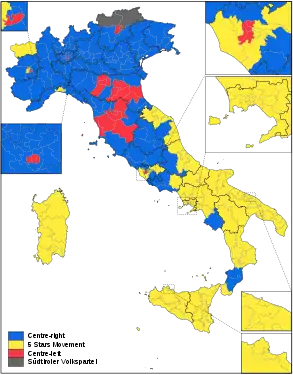

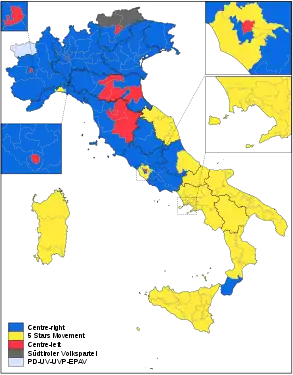

Election results maps for the Chamber of Deputies (on the left) and for the Senate (on the right). On the left, the color identifies the coalition which received the most votes in each province. On the right, the color identifies the coalition which won the most seats in respect to each Region. Blue for the Centre-right coalition, Yellow for the Five Star Movement, and Red for the Centre-left coalition. | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Voters were electing the 630 members of the Chamber of Deputies and the 315 elective members of the Senate of the Republic for the 18th legislature of the Italian Republic since 1948. The election took place concurrently with the Lombard and Lazio regional elections.

The centre-right coalition, whose main party was the right-wing League led by Matteo Salvini, emerged with a plurality of seats in the Chamber of Deputies and in the Senate, while the anti-establishment Five Star Movement led by Luigi Di Maio became the party with the largest number of votes. The centre-left coalition, led by former Prime Minister Matteo Renzi, came third.[8][9] However, no political group or party won an outright majority, resulting in a hung parliament.[10]

After three months of negotiation, a coalition was finally formed on 1 June between the M5S and the League, whose leaders both became Deputy Prime Ministers in a government led by the M5S-linked independent Giuseppe Conte as Prime Minister.[11] This coalition ended with Conte's resignation on 20 August 2019 after the League withdrew its support of the government.[12] A new coalition was formed with the center-left Democratic Party, and Conte was sworn in for a second mandate as Prime Minister on 5 September 2019.[13]

Background

At the 2013 general election none of the three main alliances – the centre-right led by Silvio Berlusconi, the centre-left led by Pier Luigi Bersani and the Five Star Movement (M5S) led by Beppe Grillo – won an outright majority in Parliament. After a failed attempt to form a government by Bersani, then-secretary of the Democratic Party (PD), and Giorgio Napolitano's re-election as President, Enrico Letta, Bersani's deputy, received the task of forming a grand coalition government. The Letta Cabinet consisted of the PD, Berlusconi's The People of Freedom (PdL), Civic Choice (SC), the Union of the Centre (UdC) and others.[14]

On 16 November 2013, Berlusconi launched a new party, Forza Italia (FI),[15] named after the defunct Forza Italia party (1994–2009). Additionally, Berlusconi announced that FI would be opposed to Letta's government, causing the split from the PdL/FI of a large group of deputies and senators led by Minister of Interior Angelino Alfano, who launched the alternative New Centre-Right (NCD) party and remained loyal to the government.[16]

Following the election of Matteo Renzi as Secretary of the PD in December 2013, there were persistent tensions culminating in Letta's resignation as Prime Minister in February 2014. Subsequently, Renzi formed a government based on the same coalition (including the NCD), but in a new fashion.[17] The new Prime Minister had a strong mandate from his party and was reinforced by the PD's strong showing in the 2014 European Parliament election[18] and the election of Sergio Mattarella, a fellow Democrat, as President in 2015. While in power, Renzi implemented several reforms, including a new electoral law (which would later be declared partially unconstitutional by the Constitutional Court), a relaxation of labour and employment laws (known as Jobs Act) with the intention of boosting economic growth, a thorough reform of the public administration, the simplification of the civil trial, the recognition of same-sex unions (not marriages) and the abolition of several minor taxes.[19][20]

As a result of the Libyan civil war, a major problem faced by Renzi was the high level of illegal immigration to Italy. During his tenure, there was an increase in the number of immigrants rescued at sea being brought to southern Italian ports, prompting criticism from the M5S, FI and Northern League (LN),[21][22] and causing a loss of popularity for Renzi.[23] However, well into 2016 opinion polls registered the PD's strength, as well as the growth of the M5S, the LN and Brothers of Italy (FdI), FI's decline, SC's virtual disappearance and the replacement of Left Ecology Freedom (SEL) with the Italian Left (SI).

In December 2016, a constitutional reform proposed by Renzi's government and duly approved by Parliament was rejected in a constitutional referendum (59% to 41%). Under the reform, the Senate would have been composed of 100 members: 95 regional representatives and five presidential appointees.[24][25][26] Following defeat, Renzi stepped down as Prime Minister and was replaced by his Minister of Foreign Affairs Paolo Gentiloni, another Democrat.[27]

In early 2017, in opposition to Renzi's policies, some left-wing Democrats led by Bersani, Massimo D'Alema and Roberto Speranza launched, along with SI splinters, the Democratic and Progressive Movement (MDP).[28][29] Contextually, the NCD was transformed into Popular Alternative (AP). In April Renzi was re-elected secretary of the PD and thus the party's candidate for Prime Minister,[30] defeating Minister of Justice Andrea Orlando and Governor of Apulia Michele Emiliano.[31][32]

In May 2017, Matteo Salvini was re-elected federal secretary of the LN and launched his own bid.[33][34] Under Salvini, the party had emphasised Euroscepticism, opposition to immigration and other populist policies.[35] In fact, Salvini's aim had been to re-launch the LN as a "national" or, even, "Italian nationalist" party, withering any notion of northern separatism. This focus became particularly evident in December when LN presented its new electoral logo, without the word "Nord".[36]

In September 2017, Luigi Di Maio was selected as candidate for Prime Minister and "political head" of the M5S, replacing Grillo.[37][38] However, even in the following months, the populist comedian was accused by critics of continuing to play his role as de facto leader of the party, while an increasingly important, albeit unofficial, role was assumed by Davide Casaleggio, son of Gianroberto, a web strategist who founded the M5S along with Grillo in 2009 and died in 2016.[39][40][41] In January 2018, Grillo separated his own blog from the movement; his blog was used in the previous years as an online newspaper of the M5S and the main propaganda tool.[42] This event was seen by many as the proof that Grillo was slowly leaving politics.[43]

The autumn registered some major developments to the left of the political spectrum: in November Forza Europa, the Italian Radicals and individual liberals launched a joint list named More Europe (+Eu), led by the long-time Radical leader Emma Bonino;[44] in December the MDP, SI and Possible launched a joint list named Free and Equal (LeU) under the leadership of Pietro Grasso, President of the Senate and former anti-mafia prosecutor;[45] the Italian Socialist Party, the Federation of the Greens, Civic Area and Progressive Area formed a list named Together in support of the PD;[46] the Communist Refoundation Party, the Italian Communist Party, social centres, minor parties, local committees, associations and groups launched a far-left joint list named Power to the People (PaP), under the leadership of Viola Carofalo.[47]

In late December, the centrist post-NCD Popular Alternative (AP), which had been a key coalition partner for the PD, divided itself among those who wanted to return into the centre-right's fold and those who supported Renzi's coalition. Two groups of AP splinters (one led by Maurizio Lupi and the other by Enrico Costa), formed along with Direction Italy, Civic Choice, Act!, Popular Construction and the Movement for the Autonomies, a joint list within the centre-right, named Us with Italy (NcI).[48] The list was later enlarged to the Union of the Centre and other minor parties.[49] The remaining members of AP, Italy of Values, the Centrists for Europe, Solidary Democracy and minor groups joined forces in the pro-PD Popular Civic List (CP), led by Minister of Health Beatrice Lorenzin.[50]

On 28 December 2017, President Sergio Mattarella dissolved Parliament and a new general election was called for 4 March 2018.[51]

On 21 February 2018, Marco Minniti, the Italian Minister of the Interior, warned "There is a concrete risk of the mafias conditioning electors' free vote".[52] Predominately the Sicilian Mafia have been recently active in Italian election meddling, the Camorra and 'Ndrangheta organisations have also taken an interest.[53]

In late February, Berlusconi indicated the President of the European Parliament, Antonio Tajani, as his candidate for the premiership if the centre-right won the general election[54] and if Forza Italia received at least the plurality of the votes inside the coalition, condition that did not occur, resulting in a victory of the party led by Matteo Salvini, the League.

Campaign

The first phase of the electoral campaign was marked by the statement of the President Mattarella to parties for the presentation of "realistic and concrete" proposals during the traditional end of the year's message, in which he also expressed the wish for a high participation in the ballot.[55]

Electoral programmes

The electoral programme of the PD included, among the main points, the introduction of a minimum hourly wage of €10, a measure that would affect 15% of workers, that is those workers who do not adhere to the national collective agreements; a cut of the contributory wedge for permanent contracts; a relocation allowance and an increase in subsidies for the unemployed; a monthly allowance of €80 for parents for each minor child; fiscal detraction of €240 for parents with children; and the progressive reduction of the rates of IRPEF and IRES, respectively the income tax and the corporate tax.[56][57][58] Regarding immigration, which had been a major problem in Italy for the previous years, the PD advocated a reduction in migrant flows through bilateral agreements with the countries of origin and pretended to a halt to EU funding for countries like Hungary and Poland that have refused to take in any of the 600,000 migrants who have reached Italy through the Mediterranean over the past four years.[59] Among the PD's allies, the CP proposed free nurseries, a tax exemption for corporate welfare and other measures regarding public health, including the contrast to the long waiting list in hospitals, the abolition of the so-called "supertickets", and an extension of home care for the elderly.[60] +Eu advocated the re-launch of the process of European integration and federation, towards the formation of the United States of Europe.[61] This focus, regarding the European process of integration, was also strongly supported by the PD.[62] More Europe also strongly advocated the social integration of migrants, quietly opposing the PD's policies implemented by the Minister of Interior Marco Minniti.[63]

The main proposal of the centre-right coalition was a huge tax reform based on the introduction of a flat tax: for Berlusconi initially based on the lowest current rate (23%) with the threshold raised to €12,000, then proceeding to a gradual reduction of the rate; while according to Salvini the tax rate should be only 15%. The economic newspaper Il Sole 24 Ore estimated the cost of this measure at around €25 billion per year calculated with a 20% rate, or €40 billion with 15%.[64] Berlusconi also proposed the cancellation of IRAP, a tax on productivity, the increase of minimum pensions to €1,000, the introduction of a "dignity income" to fight poverty, the end of contribution on youth recruitment, changes to the Fornero law, which regulated pensions, and the launch of a "Marshall Plan" for Africa to reduce illegal immigration to Italy.[65] Within FI there are some representatives of the Animalist Movement (MA) led by Michela Brambilla, whose main focus is in particular the banning of fur clothing and stricter controls in circuses, free veterinary care and the establishment of an ombudsman for animal rights.[66] The Lega additionally proposed the complete replacement of the Fornero law and the possibility of retirement with 41 years of contributions, the "scrapping" of tax records for taxpayers in difficulty, an operation that should yield up to €35 billion to the State, the disbandment of Equitalia, the company that deals with the collection of taxes, the abolition of the limit on the use of cash, the regularization of prostitution;[67] moreover, Salvini's main aim is a drastic reduction of illegal immigration, by reintroducing border controls, blocking arrivals and repatriating all migrants who have no right to stay in Italy.[68] The FdI proposed free nurseries, a check for €400 per month for newborns up to the six years old, to increase population growth, parental leave paid to 80% up to the sixth year of birth, increase in salaries and equipment to law enforcement, the increased use of the Italian Army as a measure to fight crime and a new law on self-defense.[69]

The M5S presented a programme whose main points are the introduction of a basic income, known as "income of citizenship", to fight poverty, a measure that would cost between €15 and €20 billion annually; the cut of the public debt by 40 points in relation to GDP in ten years; the adoption of measures to revitalise youth employment; a cut in pensions of over €5,000 net not entirely based on the contribution method; the reduction of IRPEF rates and the extension of the income tax threshold; the increase in spending on family welfare measures from 1.5 to 2.5% of GDP; a constitutional law that obliges members of Parliament to resign if they intend to change party, which by now is unconstitutional.[70] Di Maio also proposed a legislative simplification, starting with the elimination of almost 400 laws with a single legislative provision.[71]

LeU focused on the so-called right to study, proposing in particular the abolition of university fees for students who take the exams regularly, with the estimated cost for the state budget of €1.6 billion. LeU also proposed the reintroducing the workers' statutory protections which were eliminated by the Renzi government's Jobs Act, fighting tax evasion, corruption and organised crime.[72]

Macerata murder and subsequent attack

On 3 February 2018, a drive-by shooting event occurred in the city of Macerata, Marche in Central Italy where six African migrants were seriously wounded.[73] A 28-year-old local man, Luca Traini, was arrested and charged with attempted murder, and was also charged for the attack against the local headquarters of the ruling PD party.[74] After the attack, Traini reportedly had an Italian flag draped on his shoulders and raised his arm in the fascist salute.[75] Traini stated that the attack was "revenge" for Pamela Mastropietro, an 18-year-old Roman woman whose dismembered body had been found few days earlier, stuffed into two suitcases and dumped in the countryside; for this, three Nigerian drug dealers were arrested, the main suspect being 29-year-old failed asylum seeker, named Innocent Oseghale.[76][77][78] Missing body parts had sparked allegations of the murder having been a muti killing, also involving cannibalism.[79]

The case sparked anger and anti-immigrant sentiment in Macerata. Traini's lawyer reported "alarming solidarity" for Traini expressed by the populace, while Mastropietro's mother publicly thanked Traini for "lighting a candle" for her daughter.[80] A second autopsy of the girl's remains, published after the attack against the African migrants, revealed that Mastropietro had been strangled, stabbed, and then flayed while still alive.[81] The murder of Mastropietro and the attack by Traini, and their appraisal by Italian media and the public were "set to become a decisive factor" in the national elections.[82]

Traini was a member and former local candidate of the League, and many political commentators, intellectuals and politicians harshly criticized party leader Matteo Salvini, in connection with the attack, accusing him of having "spread hate and racism" in the country. Particularly, Roberto Saviano, the notable anti-mafia writer, labeled Salvini as the "moral instigator" of Traini's attack.[83] Salvini responded to critics by accusing the centre-left government of responsibility for Mastropietro's death through allowing migrants to stay in the country and having "blood on their hands", asserting that the blame lies with those who "fill [Italy] with illegal immigrants".[84]

Prime Minister Gentiloni stated that he "trusts in the sense of responsibility of all political forces. Criminals are criminals and the state will be particularly harsh with anyone that wants to fuel a spiral of violence." Gentiloni added that "hate and violence will not divide Italy".[85] Also, Minister of the Interior Marco Minniti harshly condemned the attack against the Africans, saying that any political party must "ride the hate".[86] Renzi, whose party was also accused about its position on immigration, stated that "calm and responsibility" from all political forces would now be necessary.[87]

Eventually, in the constituency of Macerata, the centre-right coalition, led by the League, won a plurality of the votes in the ballot, electing candidate Tullio Patassini, and showed an increase from 0.4% of the vote in 2013 to 21% in 2018, five years later.

Main parties' slogans

| Party | Original slogan | English translation | Refs | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Democratic Party | Avanti, insieme | "Forward, together" | [88][89] | |

| Five Star Movement | Partecipa, Scegli, Cambia | "Participate, Choose, Change" | [90][91] | |

| Forza Italia | Onestà, Esperienza, Saggezza | "Honesty, Experience, Wisdom" | [92][93] | |

| League | Prima gli Italiani | "Italians First" | [94][95] | |

| Free and Equal | Per i molti, non per i pochi | "For the many, not the few" | [96][97] | |

| Brothers of Italy | Il voto che unisce l'Italia | "The vote that unites Italy" | [98][99] | |

| More Europe | Più Europa, serve all'Italia | "More Europe, Italy needs it" | [100][101] | |

| Together | Insieme è meglio | "Together is better" | [102][103] | |

| Popular Civic List | Il vaccino contro gli incompetenti | "The vaccine against the incompetents" | [104][105] | |

| Power to the People | Potere al Popolo | "Power to the People" | [106][107] | |

| CasaPound Italy | Vota più forte che puoi | "Vote as strong as you can" | [108][109] | |

Electoral debates

Differently from many other Western countries, in Italy the electoral debates between parties' leaders are not so common before general elections;[110] in fact the last debate between the two main candidates to premiership dated back to the 2006 general election between Silvio Berlusconi and Romano Prodi.[111] In recent years, with few exceptions, almost every main political leader had denied his participation to an electoral debate with other candidates, preferring interviews with TV hosts and journalists.[112][113][114][115]

However, many debates took places between other leading members of the main parties.

| Italian general election debates, 2018 | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Date | Organiser | Moderator | P Present NI Non-invitee A Absent invitee | ||||||||

| Centre-left | Centre-right | M5S | LeU | ||||||||

| 7 November | La7 (Di Martedì) |

Giovanni Floris | P Renzi |

NI | A Di Maio |

NI | |||||

| 12 December | Rai 3 (#cartabianca) |

Bianca Berlinguer | P Martina |

P Brunetta |

NI | NI | |||||

| 16 January | Rai 3 (#cartabianca) |

Bianca Berlinguer | P Orlando |

P De Girolamo |

NI | NI | |||||

| 30 January | Rai 3 (#cartabianca) |

Bianca Berlinguer | P Emiliano |

P Fedriga |

NI | NI | |||||

| 13 February | La7 (Otto e mezzo) |

Lilli Gruber | NI | P Salvini |

NI | P Boldrini | |||||

| 13 February | Rai 3 (#cartabianca) |

Bianca Berlinguer | P Lorenzin |

NI | P Giarrusso |

NI | |||||

| 27 February | Rai 3 (#cartabianca) |

Bianca Berlinguer | NI | P De Girolamo |

NI | P Speranza | |||||

New electoral system

As a consequence of the 2016 constitutional referendum and of two different sentences of the Constitutional Court, the electoral laws for the two houses of the Italian Parliament lacked uniformity. In October 2017, the PD, AP, FI, the LN and minor parties agreed on a new electoral law,[116] which was approved by the Chamber of Deputies with 375 votes in favour and 215 against[117] and by the Senate with 214 votes against 61.[118] The reform was opposed by the M5S, the MDP, SI, FdI and minor parties.

The so-called Rosatellum bis, after Ettore Rosato (PD leader in the Chamber), is a mixed system, with 37% of seats allocated using a first-past-the-post voting and 63% using the proportional largest remainder method, with one round of voting.[119][120]

The 630 deputies will be elected as follows:[121]

- 232 in single-member constituencies, by plurality;

- 386 in multi-member constituencies, by national proportional representation;

- 12 in multi-member abroad constituencies, by constituency proportional representation.

The 315 elective senators will be elected as follows:[121]

- 116 in single-member constituencies, by plurality;

- 193 in multi-member constituencies, by regional proportional representation;

- 6 in multi-member abroad constituencies, by constituency proportional representation.

A small, variable number of senators for life will also be members of the Senate.

For Italian residents, each house members will be elected in single ballots, including the constituency candidate and his/her supporting party lists. In each single-member constituency the deputy/senator is elected on a plurality basis, while the seats in multi-member constituencies will be allocated nationally. In order to be calculated in single-member constituency results, parties need to obtain at least 1% of the national vote. In order to receive seats in multi-member constituencies, parties need to obtain at least 3% of the national vote. Elects from multi-member constituencies will come from closed lists.[122]

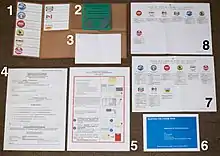

The voting paper, which is a single one for the first-past-the-post and the proportional systems, shows the names of the candidates to single-member constituencies and, in close conjunction with them, the symbols of the linked lists for the proportional part, each one with a list of the relative candidates.[123]

The voter will be able to cast their vote in three different ways:[124]

- Drawing a sign on the symbol of a list: in this case the vote extends to the candidate in the single-member constituency which is supported by that list.

- Drawing a sign on the name of the candidate of the single-member constituency and another one on the symbol of one list that supports them: the result is the same as that described above; it is not allowed, under penalty of annulment, the panachage, so the voter can not vote simultaneously for a candidate in the FPTP constituency and for a list which is not linked to them.

- Drawing a sign only on the name of the candidate for the FPTP constituency, without indicating any list: in this case, the vote is valid for the candidate in the single-member constituency and also automatically extended to the list that supports them; if that candidate is however connected to several lists, the vote is divided proportionally between them, based on the votes that each one has obtained in that constituency.

Coalitions and parties

The following table includes the coalitions and parties running in the majority of multi-member constituencies.

| Coalition | Party | Main ideology | Leader | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| League (Lega) | Right-wing populism | Matteo Salvini | |||

| Forza Italia (FI) | Liberal conservatism | Silvio Berlusconi | |||

| Brothers of Italy (FdI) | National conservatism | Giorgia Meloni | |||

| Us with Italy–UDC (NcI–UDC) | Christian democracy | Raffaele Fitto | |||

| Democratic Party (PD) | Social liberalism | Matteo Renzi | |||

| More Europe (+Eu) | Liberalism | Emma Bonino | |||

| Together | Progressivism | Giulio Santagata | |||

| Popular Civic List (CP) | Christian democracy | Beatrice Lorenzin | |||

| SVP–PATT | Regionalism | Philipp Achammer | |||

| Five Star Movement (M5S) | Populism | Luigi Di Maio | |||

| Free and Equal (LeU) | Social democracy | Pietro Grasso | |||

| Power to the People (PaP) | Communism | Viola Carofalo | |||

| CasaPound Italy (CPI) | Neo-fascism | Simone Di Stefano | |||

| The People of Family (PdF) | Social conservatism | Mario Adinolfi | |||

Opinion polling

Voter turnout

| Region | Time | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| 12:00 | 19:00 | 23:00 | |

| Abruzzo | 19.38% | 61.29% | 75.25% |

| Aosta Valley | 21.24% | 59.01% | 72.27% |

| Apulia | 17.97% | 53.68% | 68.94% |

| Basilicata | 16.27% | 53.12% | 71.11% |

| Calabria | 15.11% | 49.55% | 63.78% |

| Campania | 16.96% | 52.59% | 68.20% |

| Emilia-Romagna | 22.72% | 65.99% | 78.26% |

| Friuli-Venezia Giulia | 22.56% | 62.45% | 75.11% |

| Lazio | 18.88% | 55.47% | 72.58% |

| Liguria | 21.78% | 61.04% | 71.96% |

| Lombardy | 20.92% | 62.29% | 76.81% |

| Marche | 19.81% | 62.22% | 77.28% |

| Molise | 17.88% | 56.46% | 71.76% |

| Piedmont | 20.44% | 61.88% | 75.17% |

| Sardinia | 18.34% | 52.49% | 65.39% |

| Sicily | 14.27% | 47.06% | 62.72% |

| Tuscany | 21.17% | 63.87% | 77.34% |

| Trentino-Alto Adige | 20.85% | 60.57% | 74.34% |

| Umbria | 20.55% | 64.86% | 78.22% |

| Veneto | 22.24% | 64.61% | 78.72% |

| Total | 19.43% | 58.42% | 72.94% |

| Source: Ministry of the Interior | |||

Results for the Chamber of Deputies

Overall results

| ||||||||||||||

| Coalition | Party | Proportional | First-past-the-post | Italians abroad | Total seats |

+/− | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Votes | % | Seats | Votes | % | Seats | Votes | % | Seats | ||||||

| Centre-right coalition | League (Lega) | 5,698,687 | 17.35 | 73 | 12,152,345 | 37.00 | 49 | 240,072 | 21.43 | 2 | 125 | +109 | ||

| Forza Italia (FI) | 4,596,956 | 14.00 | 59 | 46 | 1 | 104 | +1 | |||||||

| Brothers of Italy (FdI) | 1,429,550 | 4.35 | 19 | 12 | 0 | 32 | +25 | |||||||

| Us with Italy–UDC (NcI–UDC) | 427,152 | 1.30 | 0 | 4 | 11,845 | 1.09 | 0 | 4 | New | |||||

| Total seats | 151 | 111 | 3 | 265 | – | |||||||||

| Five Star Movement (M5S) | 10,732,066 | 32.68 | 133 | 10,732,066 | 32.68 | 93 | 197,346 | 17.57 | 1 | 227 | +119 | |||

| Centre-left coalition | Democratic Party (PD) | 6,161,896 | 18.76 | 86 | 7,506,723 | 22.85 | 21 | 297,153 | 26.45 | 5 | 112 | −180 | ||

| More Europe (+Eu) | 841,468 | 2.56 | 0 | 2 | 64,350 | 5.73 | 1 | 3 | New | |||||

| Together | 190,601 | 0.58 | 0 | 1 | N/A | N/A | 0 | 1 | New | |||||

| Popular Civic List (CP) | 178,107 | 0.54 | 0 | 2 | 32.071 | 2.85 | 0 | 2 | New | |||||

| SVP–PATT | 134,651 | 0.41 | 2 | 2 | N/A | N/A | 0 | 4 | −1 | |||||

| Total seats | 88 | 28 | 6 | 122 | – | |||||||||

| Free and Equal (LeU) | 1,114,799 | 3.38 | 14 | 1,114,799 | 3.39 | 0 | 64,523 | 5.74 | 0 | 14 | New | |||

| Associative Movement Italians Abroad (MAIE) | N/A | N/A | 0 | N/A | N/A | 0 | 107,236 | 9.55 | 1 | 1 | −1 | |||

| South American Union Italian Emigrants (USEI) | N/A | N/A | 0 | N/A | N/A | 0 | 68,291 | 6.08 | 1 | 1 | – | |||

| Total | 630 | – | ||||||||||||

Proportional

| Party | Votes | % | Seats | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Five Star Movement (M5S) | 10,732,066 | 32.68 | 133 | |||

| Democratic Party (PD) | 6,161,896 | 18.76 | 86 | |||

| League (Lega) | 5,698,687 | 17.35 | 73 | |||

| Forza Italia (FI) | 4,596,956 | 14.00 | 59 | |||

| Brothers of Italy (FdI) | 1,429,550 | 4.35 | 19 | |||

| Free and Equal (LeU) | 1,114,799 | 3.39 | 14 | |||

| More Europe (+Eu) | 841,468 | 2.56 | 0 | |||

| Us with Italy–UDC (NcI–UDC) | 427,152 | 1.30 | 0 | |||

| Power to the People (PaP) | 372,179 | 1.13 | 0 | |||

| CasaPound Italy (CPI) | 312,432 | 0.95 | 0 | |||

| The People of Family (PdF) | 219,633 | 0.67 | 0 | |||

| Together (PSI–FdV–AC) | 190,601 | 0.58 | 0 | |||

| Popular Civic List (IdV–CpE–UpT–IP–AP) | 178,107 | 0.54 | 0 | |||

| South Tyrolean People's Party–PATT (SVP–PATT) | 134,651 | 0.41 | 2 | |||

| Italy for the Italians (FN–FT) | 126,543 | 0.39 | 0 | |||

| Communist Party (PC) | 106,816 | 0.33 | 0 | |||

| Human Value Party (PVU) | 47,953 | 0.15 | 0 | |||

| 10 Times Better (10VM) | 37,354 | 0.11 | 0 | |||

| For a Revolutionary Left (PCL–SCR) | 29,364 | 0.09 | 0 | |||

| Italian Republican Party–ALA (PRI–ALA) | 20,943 | 0.06 | 0 | |||

| Great North (GN) | 19,846 | 0.06 | 0 | |||

| Autodetermination | 19,307 | 0.06 | 0 | |||

| People's List for the Constitution (LdP) | 9,921 | 0.02 | 0 | |||

| Pact for Autonomy (PpA) | 7,079 | 0.02 | 0 | |||

| National Bloc for Freedoms (IR–DC) | 3,628 | 0.01 | 0 | |||

| SìAmo | 1,428 | 0.00 | 0 | |||

| Renaissance–MIR | 772 | 0.00 | 0 | |||

| Italy in the Heart | 574 | 0.00 | 0 | |||

| Total | 32,841,705 | 100.00 | 386 | |||

| Invalid / blank / unassigned votes | 1,471,727 | 4.33 | – | |||

| Total turnout | 33,923,321 | 72.94 | – | |||

| Registered voters | 46,505,499 | – | – | |||

| Source: Ministry of the Interior | ||||||

First-past-the-post

| Party or coalition | Votes | % | Seats | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Centre-right coalition (CDX) | 12,152,345 | 37.00 | 111 | |||

| Five Star Movement (M5S) | 10,727,567 | 32.68 | 93 | |||

| Centre-left coalition (CSX) | 7,506,723 | 22.85 | 28 | |||

| Free and Equal (LeU) | 1,114,799 | 3.39 | 0 | |||

| Power to the People (PaP) | 372,179 | 1.13 | 0 | |||

| CasaPound Italy (CPI) | 312,432 | 0.95 | 0 | |||

| The People of Family (PdF) | 219,633 | 0.67 | 0 | |||

| Italy for the Italians (FN–FT) | 126,543 | 0.39 | 0 | |||

| Communist Party (PC) | 106,816 | 0.33 | 0 | |||

| Human Value Party (PVU) | 47,953 | 0.15 | 0 | |||

| 10 Times Better (10VM) | 37,354 | 0.11 | 0 | |||

| For a Revolutionary Left (PCL–SCR) | 29,364 | 0.09 | 0 | |||

| Italian Republican Party–ALA (PRI–ALA) | 20,943 | 0.06 | 0 | |||

| Great North (GN) | 19,846 | 0.06 | 0 | |||

| Autodetermination | 19,307 | 0.06 | 0 | |||

| Others | 23,402 | 0.07 | 0 | |||

| Total | 32,841,025 | 100.00 | 231 | |||

| Invalid / blank / unassigned votes | 1,471,727 | 4.33 | – | |||

| Total turnout | 33,923,321 | 72.94 | – | |||

| Registered voters | 46,505,499 | – | – | |||

| Source: Ministry of the Interior | ||||||

Italians abroad

Twelve members of the Chamber of Deputies are elected by Italians abroad. Two members are elected for North America and Central America (including most of the Caribbean), four members for South America (including Trinidad and Tobago), five members for Europe, and one member for the rest of the world (Africa, Asia, Oceania, and Antarctica). Voters in these regions select candidate lists and may also cast a preference vote for individual candidates. The seats are allocated by proportional representation.

The electoral law allows for parties to form different coalitions on the lists abroad, compared to the lists in Italy; in fact Forza Italia, League and Brothers of Italy formed a unified list for abroad constituencies.[125]

| Party (or a unified coalition list) | Votes | % | Seats | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Democratic Party (PD) | 297,153 | 26.45 | 5 | |||

| League – Forza Italia – Brothers of Italy (Lega–FI–FdI) | 240,702 | 21.43 | 3 | |||

| Five Star Movement (M5S) | 197,346 | 17.57 | 1 | |||

| Associative Movement Italians Abroad (MAIE) | 107,236 | 9.55 | 1 | |||

| South American Union Italian Emigrants (USEI) | 68,291 | 6.08 | 1 | |||

| Free and Equal (LeU) | 64,523 | 5.74 | 0 | |||

| More Europe (+Eu) | 64,350 | 5.73 | 1 | |||

| Popular Civic List (CP) | 32,071 | 2.85 | 0 | |||

| Latin America Tricolor Union (UniTAL) | 25,555 | 2.27 | 0 | |||

| Us with Italy–UDC (NcI–UDC) | 12,396 | 1.10 | 0 | |||

| Freedom Movement | 10,590 | 0.94 | 0 | |||

| Italian Republican Party–ALA (PRI–ALA) | 2,270 | 0.20 | 0 | |||

| Free Flights to Italy | 946 | 0.08 | 0 | |||

| Total | 1,123,429 | 100.00 | 12 | |||

| Invalid / blank / unassigned votes | 156,755 | 12.42 | – | |||

| Total turnout | 1,262,422 | 29.84 | – | |||

| Registered voters | 4,230,854 | – | – | |||

| Source: Ministry of the Interior | ||||||

Results for the Senate of the Republic

Overall results

| ||||||||||||||

| Coalition | Party | Proportional | First-past-the-post | Italians abroad | Total seats |

+/− | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Votes | % | Seats | Votes | % | Seats | Votes | % | Seats | ||||||

| Centre-right coalition | League (Lega) | 5,321,537 | 17.61 | 37 | 11,327,549 | 37.50 | 21 | 226,885 | 21.98 | 0 | 58 | +39 | ||

| Forza Italia (FI) | 4,358,004 | 14.43 | 33 | 23 | 2 | 57 | –41 | |||||||

| Brothers of Italy (FdI) | 1,286,606 | 4.26 | 7 | 9 | 0 | 18 | +18 | |||||||

| Us with Italy–UDC (NcI–UDC) | 361,402 | 1.20 | 0 | 4 | 10,404 | 1.04 | 0 | 4 | New | |||||

| Total seats | 77 | 58 | 2 | 137 | – | |||||||||

| Five Star Movement (M5S) | 9,733,928 | 32.22 | 68 | 9,733,928 | 32.22 | 44 | 174,948 | 17.64 | 0 | 112 | +58 | |||

| Centre-left coalition | Democratic Party (PD) | 5,783,360 | 19.14 | 43 | 6,947,199 | 23.00 | 8 | 279,489 | 27.08 | 2 | 53 | –57 | ||

| More Europe (+Eu) | 714,821 | 2.37 | 0 | 1 | 55,625 | 5.39 | 0 | 1 | New | |||||

| Together | 163,454 | 0.54 | 0 | 1 | N/A | N/A | N/A | 1 | New | |||||

| Popular Civic List (CP) | 157,282 | 0.52 | 0 | 1 | 31,293 | 3.15 | 0 | 1 | New | |||||

| SVP–PATT | 128,282 | 0.42 | 1 | 2 | N/A | N/A | N/A | 3 | –1 | |||||

| Aosta Valley (VdA) | N/A | N/A | N/A | 1 | N/A | N/A | N/A | 1 | ±0 | |||||

| Total seats | 44 | 14 | 2 | 60 | – | |||||||||

| Free and Equal (LeU) | 991,159 | 3.28 | 4 | 991,159 | 3.28 | 0 | 55,279 | 5.57 | 0 | 4 | New | |||

| Associative Movement Italians Abroad (MAIE) | N/A | N/A | 0 | N/A | N/A | 0 | 110,879 | 10.74 | 1 | 1 | – | |||

| South American Union Italian Emigrants (USEI) | N/A | N/A | 0 | N/A | N/A | 0 | 68,233 | 6.61 | 1 | 1 | – | |||

| Total | 315 | – | ||||||||||||

Proportional

| Party | Votes | % | Seats | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Five Star Movement (M5S) | 9,733,928 | 32.22 | 68 | |||

| Democratic Party (PD) | 5,783,360 | 19.14 | 43 | |||

| League (Lega) | 5,321,537 | 17.61 | 37 | |||

| Forza Italia (FI) | 4,358,004 | 14.43 | 33 | |||

| Brothers of Italy (FdI) | 1,286,606 | 4.26 | 7 | |||

| Free and Equal (LeU) | 991,159 | 3.28 | 4 | |||

| More Europe (+Eu) | 714,821 | 2.37 | 0 | |||

| Us with Italy–UDC (NcI–UDC) | 361,402 | 1.20 | 0 | |||

| Power to the People (PaP) | 320,493 | 1.06 | 0 | |||

| CasaPound Italy (CPI) | 259,718 | 0.86 | 0 | |||

| The People of Family (PdF) | 211,759 | 0.70 | 0 | |||

| Together (PSI–FdV–AC) | 163,454 | 0.54 | 0 | |||

| Popular Civic List (IdV–CpE–UpT–IP–AP) | 157,282 | 0.52 | 0 | |||

| Italy for the Italians (FN–FT) | 149,907 | 0.50 | 0 | |||

| South Tyrolean People's Party–PATT (SVP–PATT) | 128,282 | 0.42 | 1 | |||

| Communist Party (PC) | 101,648 | 0.34 | 0 | |||

| Human Value Party (PVU) | 38,749 | 0.12 | 0 | |||

| For a Revolutionary Left (PCL–SCR) | 32,623 | 0.11 | 0 | |||

| Italian Republican Party–ALA (PRI–ALA) | 27,384 | 0.09 | 0 | |||

| Autodetermination | 20,468 | 0.07 | 0 | |||

| Great North (GN) | 17,507 | 0.06 | 0 | |||

| People's List for the Constitution (LdP) | 10,356 | 0.03 | 0 | |||

| United Right – Pitchforks | 6,229 | 0.02 | 0 | |||

| Christian Democracy (DC) | 5,532 | 0.02 | 0 | |||

| Pact for Autonomy (PpA) | 5,015 | 0.02 | 0 | |||

| SìAmo | 1,402 | 0.00 | 0 | |||

| Modern and Solidary State (SMS) | 1,384 | 0.00 | 0 | |||

| Renaissance–MIR | 552 | 0.00 | 0 | |||

| Total | 30,210,561 | 100.00 | 193 | |||

| Invalid / blank / unassigned votes | 1,398,216 | 4.48 | – | |||

| Total turnout | 31,231,814 | 73.01 | – | |||

| Registered voters | 42,780,033 | – | – | |||

| Source: Ministry of the Interior | ||||||

First-past-the-post

| Party or coalition | Votes | % | Seats | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Centre-right coalition (CDX) | 11,327,549 | 37.50 | 58 | |||

| Five Star Movement (M5S) | 9,733,928 | 32.22 | 44 | |||

| Centre-left coalition (CSX) | 6,947,199 | 23.00 | 14 | |||

| Free and Equal (LeU) | 991,159 | 3.28 | 0 | |||

| Power to the People (PaP) | 320,493 | 1.06 | 0 | |||

| CasaPound Italy (CPI) | 259,718 | 0.86 | 0 | |||

| The People of Family (PdF) | 211,759 | 0.70 | 0 | |||

| Italy for the Italians (FN–FT) | 149,907 | 0.50 | 0 | |||

| Communist Party (PC) | 101,648 | 0.34 | 0 | |||

| Human Value Party (PVU) | 38,749 | 0.12 | 0 | |||

| For a Revolutionary Left (PCL–SCR) | 32,623 | 0.11 | 0 | |||

| Italian Republican Party–ALA (PRI–ALA) | 27,384 | 0.09 | 0 | |||

| Autodetermination | 20,468 | 0.07 | 0 | |||

| Great North (GN) | 17,507 | 0.06 | 0 | |||

| Others | 30,470 | 0.10 | 0 | |||

| Total | 30,210,363 | 100.00 | 116 | |||

| Invalid / blank / unassigned votes | 1,398,216 | 4.48 | – | |||

| Total turnout | 31,231,814 | 73.01 | – | |||

| Registered voters | 42,780,033 | – | – | |||

| Source: Ministry of the Interior | ||||||

Italians abroad

| Party (or a unified coalition list) | Votes | % | Seats | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Democratic Party (PD) | 279,489 | 27.08 | 2 | |||

| League – Forza Italia – Brothers of Italy (Lega–FI–FdI) | 226,885 | 21.98 | 2 | |||

| Five Star Movement (M5S) | 182,715 | 17.70 | 0 | |||

| Associative Movement Italians Abroad (MAIE) | 110,879 | 10.74 | 1 | |||

| South American Union Italian Emigrants (USEI) | 68,233 | 6.61 | 1 | |||

| Free and Equal (LeU) | 57,761 | 5.60 | 0 | |||

| More Europe (+Eu) | 55,625 | 5.39 | 0 | |||

| Popular Civic List (CP) | 32,660 | 3.16 | 0 | |||

| Us with Italy–UDC (NcI–UDC) | 10,856 | 1.05 | 0 | |||

| Freedom Movement | 6,960 | 0.67 | 0 | |||

| Total | 1,032,063 | 100.00 | 6 | |||

| Invalid / blank / unassigned votes | 146,430 | 12.61 | – | |||

| Total turnout | 1,160,985 | 30.27 | – | |||

| Registered voters | 4,230,854 | – | – | |||

| Source: Ministry of the Interior | ||||||

Leaders' races

Di Maio and Renzi run in a single-member constituency, respectively in Acerra, near Naples, for the Chamber of Deputies and in Florence for the Senate. Salvini ran in many multi-member constituencies through the country and, due to the mechanism of the electoral law, he was elected in Calabria.[126]

| 2018 general election (C): Acerra | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Candidate | Coalition | Party | Votes | % | |

| Luigi Di Maio | M5S | 95,219 | 63.4 | ||

| Vittorio Sgarbi | Centre-right | FI | 30,596 | 20.4 | |

| Antonio Falcone | Centre-left | PD | 18,018 | 12.0 | |

| Others | 6,315 | 4.1 | |||

| Total | 150,148 | 100.0 | |||

| Turnout | 153,528 | 69.9 | |||

| 2018 general election (S): Florence | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Candidate | Coalition | Party | Votes | % | |

| Matteo Renzi | Centre-left | PD | 109,830 | 43.9 | |

| Alberto Bagnai | Centre-right | LN | 61,642 | 24.6 | |

| Nicola Cecchi | M5S | 49,925 | 19.9 | ||

| Others | 28,797 | 11.4 | |||

| Total | 250,194 | 100.0 | |||

| Turnout | 256,879 | 78.6 | |||

Maps

Winning candidates in constituencies for the Chamber of Deputies.

Winning candidates in constituencies for the Chamber of Deputies. Winning candidates in constituencies for the Senate of the Republic.

Winning candidates in constituencies for the Senate of the Republic.

Analysis of proportionality

Chamber of Deputies

The disproportionality of the Chamber of Deputies in the 2018 election was 5.50 using the Gallagher Index.

| Coalition | Vote Share(%) |

Seat Share(%) |

Difference | Difference² | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Centre-right coalition | 37.00 | 42.06 | +5.06 | 25.60 | |

| Five Star Movement | 32.68 | 36.03 | +3.35 | 11.22 | |

| Centre-left coalition | 22.85 | 19.36 | −3.49 | 12.18 | |

| Free and Equal | 3.39 | 2.22 | −1.17 | 1.37 | |

| Power to the People | 1.13 | 0.00 | −1.13 | 1.28 | |

| Others | 2.97 | 0.00 | −2.97 | 8.82 | |

| TOTAL | 60.47 | ||||

| TOTAL /2 | 30.24 | ||||

| √TOTAL /2 | 5.50 | ||||

Senate of the Republic

The disproportionality of the Senate of the Republic in the 2018 election was 6.12 using the Gallagher Index.

| Coalition | Vote Share(%) |

Seat Share(%) |

Difference | Difference² | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Centre-right coalition | 37.49 | 42.86 | +5.37 | 28.84 | |

| Five Star Movement | 32.22 | 35.56 | +3.34 | 11.16 | |

| Centre-left coalition | 22.99 | 18.41 | −4.58 | 20.98 | |

| Free and Equal | 3.28 | 1.27 | −2.01 | 4.04 | |

| Power to the People | 1.05 | 0.00 | −1.05 | 1.10 | |

| Others | 2.97 | 0.00 | −2.97 | 8.82 | |

| TOTAL | 74.93 | ||||

| TOTAL /2 | 37.47 | ||||

| √TOTAL /2 | 6.12 | ||||

Electorate demographics

| Sociology of the electorate | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Demographic | Centre-right | M5S | Centre-left | LeU | Others | Turnout |

| Total vote | 37.0% | 32.7% | 22.9% | 3.4% | 4.0% | 72.9% |

| Sex | ||||||

| Men | 36.8% | 32.8% | 22.9% | 3.5% | 4.0% | 72.5% |

| Women | 37.1% | 32.9% | 22.9% | 2.7% | 3.7% | 68.3% |

| Age | ||||||

| 18–34 years old | 34.4% | 35.3% | 21.5% | 5.0% | 3.8% | 70.1% |

| 35–49 years old | 37.4% | 35.4% | 20.3% | 2.7% | 4.2% | 72.2% |

| 50–64 years old | 38.3% | 34.0% | 20.1% | 3.2% | 4.4% | 72.4% |

| 65 or older | 36.9% | 27.1% | 30.1% | 3.0% | 2.9% | 66.3% |

| Occupation | ||||||

| Student | 29.9% | 32.3% | 24.4% | 8.2% | 5.2% | 66.8% |

| Unemployed | 41.8% | 37.2% | 15.1% | 0.6% | 5.3% | 63.7% |

| Housewife | 41.1% | 36.1% | 17.4% | 1.8% | 3.6% | 65.9% |

| Blue-collar | 42.6% | 37.0% | 14.1% | 1.3% | 5.0% | 72.0% |

| White-collar | 29.4% | 36.1% | 25.4% | 5.6% | 3.5% | 75.6% |

| Self-employed | 46.9% | 31.8% | 15.1% | 2.3% | 3.9% | 73.3% |

| Manager | 31.8% | 31.2% | 29.5% | 3.3% | 4.2% | 77.9% |

| Retired | 36.6% | 26.4% | 30.5% | 3.7% | 2.8% | 68.8% |

| Work sector | ||||||

| Public sector | 29.7% | 41.6% | 24.0% | 1.7% | 3.9% | 71.8% |

| Private sector | 35.6% | 34.0% | 22.0% | 4.3% | 4.1% | 72.7% |

| Education | ||||||

| Elementary school | 36.1% | 30.0% | 28.5% | 2.3% | 3.1% | 64.9% |

| Middle school | 42.7% | 33.3% | 18.4% | 2.2% | 3.4% | 70.5% |

| High school | 34.9% | 36.1% | 20.3% | 4.7% | 4.0% | 74.1% |

| University | 28.8% | 29.3% | 31.4% | 5.5% | 5.0% | 72.0% |

| Religious service attendance | ||||||

| Weekly or more | 38.2% | 30.9% | 26.0% | 2.2% | 2.7% | 68.9% |

| Monthly | 44.6% | 31.4% | 18.5% | 2.6% | 2.9% | 72.0% |

| Occasionally | 38.6% | 34.9% | 20.0% | 3.2% | 3.3% | 71.2% |

| Never | 30.8% | 33.7% | 24.8% | 5.2% | 5.5% | 69.9% |

| Source: Ipsos Italia[127] | ||||||

Government formation

After the election's results were known, both Luigi Di Maio and Matteo Salvini stated that they must receive from President Sergio Mattarella the task of forming a new cabinet because they led the largest party and the largest coalition, respectively.[128] On 5 March, Matteo Renzi announced that the PD will be in the opposition during this legislature and he will resign as party leader when a new cabinet is formed.[129] On 6 March, Salvini repeated his campaign message that his party would refuse any coalition with the M5S.[130] On 14 March, Salvini nonetheless offered to govern with the M5S, imposing the condition that League ally Forza Italia, led by ex premier Silvio Berlusconi, must also take part in any coalition. Di Maio rejected this proposal on the grounds that Salvini was "choosing restoration instead of revolution" because "Berlusconi represents the past".[131][132]

On 12 March, Renzi resigned as party leader and was replaced by deputy secretary Maurizio Martina.

On 24 March, the centre-right coalition and the Five Star Movement agreed on the election of presidents of the Houses of Parliament, Roberto Fico of the M5S for the Chamber and Maria Elisabetta Alberti Casellati of FI for the Senate.[133][134]

On 7 April, Di Maio made an appeal to the PD to "bury the hatchet" and consider a governing coalition with his party.[132]

On 18 April, President Mattarella gave newly-elected Senate president Alberti Casellati a so-called "exploratory mandate" to form a government of M5S and the centre-right alliance, with a two-day deadline.[135]

On 23 April, President Mattarella gave newly elected Chamber of Deputies president Fico an "exploratory mandate" to form a government between M5S and the Democratic Party, with a three-day deadline. The decision came after the previous attempt by Alberti Casellati failed to show any progress.[136]

On 30 April, following an interview of the former PD's leader Matteo Renzi who expressed his strong opposition to an alliance with the M5S, Di Maio called for new elections.[137][138][139]

On 7 May, President Mattarella held a third round of government formation talks, after which he formally confirmed the lack of any possible majority (M5S rejecting an alliance with the whole centre-right coalition, PD rejecting an alliance with both M5S and the centre-right coalition, and the League's Matteo Salvini refusing to start a government with M5S but without Berlusconi's Forza Italia party, whose presence in the government was explicitly vetoed by M5S's leader Luigi Di Maio); on the same circumstance, he announced his intention to soon appoint a "neutral government" (irrespective of M5S and League's refusal to support such an option) to take over from the Gentiloni Cabinet which was considered unable to lead Italy into a second consecutive election as it was representing a majority from a past legislature, and offering an early election in July as a realistic option to take into consideration due to the deadlock situation.[140]

On 9 May, after a day of rumours, both M5S and the League officially requested President Mattarella to give them 24 more hours to strike a government agreement between the two parties.[141] Later the same day, in the evening, Silvio Berlusconi publicly announced Forza Italia would not support a M5S-League government on a vote of confidence, but he would still maintain the centre-right alliance nonetheless, thus opening the doors to a possible majority government between the two parties.[142]

On 13 May, the Five Star Movement and League reached an agreement on a government program, likely clearing the way for the formation of a governing coalition between the two parties, but they are still negotiating the members of a government cabinet, including the prime minister. M5S and League leaders were slated to meet with Italian President Sergio Mattarella on 14 May to guide the formation of a new government.[143]

On 17 May, Five Star Movement and League agreed to the details regarding the government program, officially clearing the way for the formation of a governing coalition between the two parties.[144] The final draft of their program was then published on 18 May.[145]

On 18 May, 44,796 members of the Five Star Movement cast their vote online on the matter concerning the government agreement, with 42,274, more than 94%, voting in favour.[146][147] A second vote sponsored by the Northern League then took place on 19 May and 20 May and was open to the general public.[148] On 20 May, it was announced that approximately 215,000 Italian citizens had participated in the Northern League election, with around 91 percent supporting the government agreement.[149]

On 21 May, the Five Star Movement and the League proposed law professor Giuseppe Conte as Prime Minister.[150][151] On 23 May, Conte was invited to the Quirinal Palace to receive the task of forming a new cabinet and was granted a mandate by Italian President Mattarella.[152][153]

However, on 27 May 2018, the designated Prime Minister Conte renounced to his office, due to contrasts between the League's leader Salvini and President Mattarella. In fact, Salvini proposed the university professor Paolo Savona as Minister of Economy and Finances, but Mattarella strongly opposed him, considering Savona too Eurosceptic and anti-German.[154] In his speech after Conte's resignation, Mattarella declared that the two parties wanted to bring Italy out of the Eurozone, and as the guarantor of Italian Constitution and country's interest and stability he could not allow this.[155][156] On the following day, Mattarella gave Carlo Cottarelli, an economist and former IMF director, the task of forming a new government.[157]

In the statement released after the designation, Cottarelli specified that in case of confidence by the Parliament, he would contribute to the approval of the budget law for 2019, then the Parliament would be dissolved and a new general election would be called for the beginning of 2019. In the absence of confidence, the government would deal only with the so-called current affairs and lead the country toward new elections after August 2018. Cottarelli also guaranteed the neutrality of the government and the commitment not to run for the next election.[158] He ensured a prudent management of Italian national debt and the defense of national interests through a constructive dialogue with the European Union.[159]

On 28 May 2018, the Democratic Party announced that they will vote the confidence to Cottarelli, while the Five Star Movement and the centre-right parties Forza Italia, Brothers of Italy and the League announced their vote against.[160][161] Cottarelli was expected to submit his list of ministers for approval to President Mattarella on 29 May. However, on 29 May and 30 May he held only informal consultations with the President. According to the Italian media, he is facing difficulties due to the unwillingness of several potential candidates to serve as ministers in his cabinet and may even renounce.[162][163] Meanwhile, Matteo Salvini and Luigi Di Maio announced their willingness to restart the negotiations to form a political government, and the leader of Brothers of Italy Giorgia Meloni gave her support to the initiative.[162][163][164] The government was formed the following day.

See also

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to 2018 elections in Italy. |

Notes

- The centre-right did not run with a single coalition leader. On the basis of an agreement between the leaders of the centre-right coalition parties (Matteo Salvini, Silvio Berlusconi and Giorgia Meloni), in case of electoral victory, the party that had received the most votes could have proposed its own candidate for Prime Minister on behalf of the entire coalition during the consultations with the President of the Republic. Salvini, as leader of the most voted party within the coalition (the League), was therefore the Prime Minister candidate of the centre-right.

- Renzi was the leader of the Democratic Party since 15 December 2013. However, Renzi resigned after the failed 2016 constitutional referendum only to re-win the Democratic Party leadership on 30 April 2017.

- Salvini ran as capolista (list leader) for the League in five constituencies, namely Calabria 1, Lazio 1, Lombardy 4, Liguria 1 and Sicily 2.[2] He was originally elected in the Calabria 1 constituency. On 31 July 2019 the electoral commission of the Senate finally ruled for assigning Salvini's contested seat to Forza Italia; Salvini then took the Lazio 1 seat in substitution of the League senator Papaevangeliu.[3][4]

References

- "Eligendo: Camera [Votanti] Italia (Italia) - Camera dei Deputati del 4 marzo 2018 - Ministero dell'Interno". Eligendo.

- "Elezioni: Salvini Capolista al Senato in 5 circosrizioni" (in Italian). agvilvelino.it. 29 January 2018. Retrieved 12 September 2019.

- Tornago, Andrea (17 July 2019). "Salvini vicino a perdere il seggio in Calabria. Traballa la maggioranza del governo in Senato". Repubblica.it (in Italian). Retrieved 19 September 2019.

- "senato.it - Scheda di attività di Matteo SALVINI - XVIII Legislatura". senato.it (in Italian). Senate of the Republic. Retrieved 19 September 2019.

- "Camera Collegio uninominale 03 - ACERRA". Ministry of the Interior. 4 March 2018. Retrieved 7 March 2018.

- "Senato Collegio uninominale 01 - FIRENZE". Ministry of the Interior. 4 March 2018. Retrieved 7 March 2018.

- Francesco Verderami (13 December 2017). "Elezioni 2018, si punta al 27 dicembre per lo scioglimento delle Camere: si vota il 4 marzo". Corriere.it (in Italian). Retrieved 26 February 2018.

- "Elezioni politiche: vincono M5s e Lega. Crollo del Partito democratico. Centrodestra prima coalizione. Il Carroccio sorpassa Forza Italia". 4 March 2018.

- Sala, Alessandro. "Elezioni 2018: M5S primo partito, nel centrodestra la Lega supera FI".

- "Italy election to result in hung parliament | DW | 05.03.2018". DW.COM.

- "Italy: Conte to lead 'government of change'". ANSAMed. 1 June 2018. Retrieved 7 September 2019.

- Giuffrida, Angela (20 August 2019). "Italian PM resigns with attack on 'opportunist' Salvini". The Guardian. Retrieved 7 September 2019.

- Tidey, Alice (5 September 2019). "Conte PM & Di Maio foreign minister as new Italian government sworn in". Euronews. Retrieved 7 September 2019.

- Dionisi, Brenda (9 May 2013). "It's a governissimo!". The Florentine. Archived from the original on 10 December 2014. Retrieved 24 September 2013.

- "Berlusconi breaks away from Italian government after party splits". Reuters. 16 November 2013. Archived from the original on 2 December 2013.

- "Archivio Corriere della Sera". archivio.corriere.it. Archived from the original on 3 December 2013.

- "Renzi: con 47, 8 anni di media, è il governo più giovane di sempre". Corriere Della Sera. 21 February 2014. Retrieved 23 February 2014.

- "UPDATE 2-Renzi's triumph in EU vote gives mandate for Italian reform". Reuters. Retrieved 9 June 2015.

- "Italy Prime Minister Mattro Renzi on Senate Reform". Bloomberg. Retrieved 29 September 2015.

- "Renzi Gives Italians Lower Taxes, Higher Cash Use to Back Growth". Bloomberg. Retrieved 15 October 2015.

- "Italy PM Renzi attacks northern regions for refusing migrants". BBC News. 8 June 2015

- "Italy coastguard: 3,000 migrants rescued in one day in Mediterranean". The Guardian. 23 August 2015.

- "L'analisi del sondaggista: "Con l'immigrazione, Renzi perde tra i 2 e i 4 milioni di voti"" (in Italian). Ilgiornale.it. 25 August 2015. Retrieved 4 March 2018.

- "Italian parties reach deal on Senate reform". Reuters. 21 June 2014. Retrieved 25 June 2014.

- Politi, James (13 October 2015). "Renzi wins Senate victory over Italy's political gridlock". Financial Times. ISSN 0307-1766. Retrieved 6 August 2016.

- "Italy's constitutional reform gets the green light from the Senate, the opposition leaves the floor". il Sole 24 Ore. Retrieved 6 August 2016.

- Rovelli, Michela (11 December 2016). "Governo, Gentiloni accetta l'incarico di governo: "Un grande onore"". Corriere della Sera. Retrieved 11 December 2016.

- Franco Stefanoni. "Ecco il nome degli ex Pd: Articolo 1 Movimento dei democratici e progressisti". Corriere.it. Retrieved 4 March 2018.

- ""Democratici e progressisti" il nuovo nome degli ex Pd. Speranza: lavoro è nostra priorità". Ilsole24ore.com. 25 February 2017. Retrieved 4 March 2018.

- "Primarie Pd, Renzi vince nettamente: "Al fianco del governo"". Repubblica.it. 30 April 2017. Retrieved 4 March 2018.

- Huffington Post. "I dati definitivi delle primarie: Renzi 70%, Orlando 19,5%, Emiliano 10,49%". Huffingtonpost.it. Retrieved 4 March 2018.

- "Primarie - Partito Democratico". Primarie Partito Democratico. Archived from the original on 25 March 2019. Retrieved 27 April 2019.

- Altri articoli dalla categoria (14 May 2017). "Primarie Lega, Salvini centra l'obiettivo: con l'82,7% resta segretario. L'attacco di Bossi: "Con lui la Lega è finita"". Milano.repubblica.it. Retrieved 4 March 2018.

- "Lega, Salvini avverte Berlusconi: "Maggioritario se vuoi davvero vincere"". Affaritaliani.it. Retrieved 4 March 2018.

- "Continent of Fear: The Rise of Europe's Right-Wing Populists". spiegel.de. Retrieved 3 January 2015.

- "Lega. Ecco il simbolo, via Nord ma con Salvini premier". Rainews.it. 27 November 2013. Retrieved 4 March 2018.

- Altri articoli dalla categoria (23 September 2017). "M5s, Di Maio eletto candidato premier e nuovo capo politico. Ma alle primarie votano solo in 37 mila". Repubblica.it. Retrieved 4 March 2018.

- Marco Imarisio. "Movimento 5 Stelle: l'incoronazione gelida. E Di Maio promette a tutti "disciplina e onore"". Corriere.it. Retrieved 4 March 2018.

- Di martedì 19 aprile 2016 (19 April 2016). "Chi comanda ora nel Movimento 5 Stelle? | Il ruolo di Davide Casaleggio". Polisblog.it. Retrieved 18 April 2017.

- Altri articoli dalla categoria (21 September 2016). "M5s, la prima volta di Davide Casaleggio". Repubblica.it. Retrieved 18 April 2017.

- "Il nuovo regolamento M5S e il ruolo di Davide Casaleggio nelle espulsioni". Nextquotidiano.it. 26 September 2016. Retrieved 18 April 2017.

- "Il blog di Beppe Grillo è cambiato". 23 January 2018.

- "Grillo si riprende il blog e continua il suo distacco dal M5S". Espresso.repubblica.it. 15 January 2018. Retrieved 4 March 2018.

- "I radicali alle elezioni da soli: la nuova lista si chiamerà "+ Europa"". Lastampa.it. 23 November 2017. Retrieved 4 March 2018.

- "Liberi e Uguali, Grasso si presenta bene". Ilmanifesto.it. Retrieved 4 March 2018.

- "Ritorna, in piccolo, L'Ulivo e l'avversario è sempre lo stesso: "Siamo gli unici che hanno battuto due volte Berlusconi"". Huffingtonpost.it. 14 December 2017. Retrieved 4 March 2018.

- "Viola Carofalo, National Spokesman of "Potere al Popolo"". Poterealpopolo.org. 10 February 2018. Retrieved 4 March 2018.

- "Nasce Noi con l'Italia, la 'quarta gamba' del centrodestra" (in Italian). Ilgiornale.it. 19 December 2017. Retrieved 4 March 2018.

- "Simbolo e liste: è pronta la "quarta gamba"" (in Italian). Ilgiornale.it. 19 December 2017. Retrieved 4 March 2018.

- "Nasce "Civica popolare", lista centrista alleata col Pd: sarà guidata dalla Lorenzin". Repubblica.it. 29 December 2017. Retrieved 4 March 2018.

- Ball, Deborah; Legorano, Giovanni (28 December 2017). "Italy's President Calls National Elections, as Country Grapples With Economic Pain" – via The Wall Street Journal.

- "Italians warned of Mafia meddling in the upcoming election". Holly Ellyatt. CNBC. 22 February 2018. Retrieved 22 February 2018.

- "Mafia risk on elections - Minniti". ANSA. Retrieved 22 February 2018.

- Cooper, Harry (23 February 2018). "Berlusconi indicates Tajani will be his choice for PM". Politico.eu. Retrieved 4 March 2018.

- "Mattarella, il discorso di fine anno: "I partiti hanno il dovere di programmi realistici. Fiducia nei giovani al voto"". Ilfattoquotidiano.it. Retrieved 4 March 2018.

- "Programma PD - Elezioni Politiche 2018". 7 February 2018.

- "Porta a Porta, puntata del 10 Gennaio 2018". Raiplay.it. Retrieved 4 March 2018.

- Altri articoli dalla categoria (2 February 2018). "Pd, Renzi ecco il programma elettorale: 240 euro al mese per figlio. "Taglio contributi tempo indeterminato"". Repubblica.it. Retrieved 4 March 2018.

- Cooper, Harry (13 February 2018). "Italian election pledges: Pizza or pazza?". Politico.eu. Retrieved 4 March 2018.

- "Porta a Porta, puntata del 16 Gennaio 2018". Raiplay.it. Retrieved 4 March 2018.

- Altri articoli dalla categoria (23 November 2017). "Radicali italiani, ecco la lista europeista di Bonino e Della Vedova". Repubblica.it. Retrieved 4 March 2018.

- "Renzi: il futuro sono gli Stati Uniti d'Europa". Ilsole24ore.com. 20 January 2018. Retrieved 4 March 2018.

- "Migranti e legittima difesa, è campagna sulla sicurezza". Ilsole24ore.com. 13 February 2018. Archived from the original on 14 February 2018. Retrieved 4 March 2018.

- "Dalla flat tax all'abolizione della legge Fornero, quanto costano le promesse elettorali dei partiti". Ilsole24ore.com. 1 January 2018. Retrieved 4 March 2018.

- "Porta a Porta, puntata dell'11 Gennaio 2018". Raiplay.it. Retrieved 4 March 2018.

- ""Stop agli allevamenti per le pellicce e interventi nei circhi": il programma animalista di Berlusconi". Lastampa.it. 20 January 2018. Retrieved 4 March 2018.

- "Porta a Porta, puntata del 18 Gennaio 2018". Raiplay.it. Retrieved 4 March 2018.

- "Immigrati occupano la Statale, Salvini: "Stanno male? Rispediamoli a casa loro!"". Ilpopulista.it. 16 January 2018. Retrieved 4 March 2018.

- "Porta a Porta, puntata del 17 Gennaio 2018". Raiplay.it. Retrieved 4 March 2018.

- "Porta a Porta, puntata del 9 Gennaio 2018". Raiplay.it. Retrieved 4 March 2018.

- "M5S, Di Maio: "Ridurre la burocrazia, aboliremo 400 leggi". E lancia un sito ad hoc aperto a tutti". Repubblica.it. 10 January 2018. Retrieved 4 March 2018.

- "Grasso: "Eliminare il canone Rai? Noi vogliamo abolire le tasse per l'università come in Germania. E cancellare il Jobs Act"". Ilfattoquotidiano.it. 24 October 2017. Retrieved 4 March 2018.

- Elisabetta Povoledo (3 February 2018). "'Racial Hatred' Cited After African Immigrants Are Shot in Italy". The New York Times. Retrieved 4 March 2018.

- "Raid razzista a Macerata, colpita anche la sede Pd". Repubblica.it. 3 February 2018. Retrieved 4 March 2018.

- Pitrelli, Stefano; Birnbaum, Michael (3 February 2018). "Man shoots, wounds at least 6 'people of color' in Italian city amid tensions" – via www.washingtonpost.com.

- "Macerata, spari da auto in corsa, sei feriti: sono tutti di colore. Una vendetta per Pamela: bloccato un uomo avvolto nel tricolore". Ilmessaggero.it. Retrieved 4 March 2018.

- "Nigerian charged over dismembered teen (4) - English". ANSA.it. 1 February 2018.

- Squires, Nick; Agency, Reuters News (3 February 2018). "Italian man arrested after African migrants injured in drive-by shootings" – via The Telegraph.

- Il Fatto QUotidiano, 31 January 2018. Corriere 21 February 2018. Libero Quotidiano 23 February 2018.

- Libero Quotidiano 6 February 2018, Repubblica, 5 February 2018.

- Libero Quotidiano 22 February 2018. Il Giornale 22 February 2018.

- Laura Mowat, Italy election 2018: How immigration and a weak economy could decide the fate of EUROPE, Sunday Express, 20 February 2018.

- Huffington Post. "Roberto Saviano: "Il mandante morale dei fatti di Macerata è Salvini"". Huffingtonpost.it. Retrieved 4 March 2018.

- Altri articoli dalla categoria (3 February 2018). "Raid razzista a Macerata, Salvini: "Colpa di chi ci riempie di clandestini". Renzi: "Ora calma e responsabilità"". Repubblica.it. Retrieved 4 March 2018.

- Huffington Post. "Gentiloni: "Odio e violenza non-ci divideranno". Renzi e Di Maio non-cavalcano i fatti di Macerata: "Ora calma, non-strumentalizziamo"". Huffingtonpost.it. Retrieved 4 March 2018.

- Redazione ANSA (27 January 2018). "Macerata: Minniti, nessuno cavalchi odio". Ansa.it. Retrieved 4 March 2018.

- "Renzi: "Servono calma e responsabilità"". Rai.it. 3 February 2018. Retrieved 4 March 2018.

- "Avanti, insieme - Partito Democratico". 30 April 2017.

- "Avanti, insieme.Mozione congressuale di Matteo Renzi - Partito Democratico". 16 March 2017.

- Massimo Derosa (22 January 2018). "Partecipa, Scegli, Cambia". Massimoderosa.it. Retrieved 4 March 2018.

- 24.01.18 13:05. "Partecipa, Scegli, Cambia anche in Europa con la consultazione pubblica sulla sicurezza alimentare". Efdd-m5seuropa.com. Archived from the original on 14 March 2018. Retrieved 4 March 2018.CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link)

- "Forza Italia lancia primo manifesto: onestà, esperienza, saggezza". 14 January 2018.

- Redazione (2 February 2018). "Coniato il primo manifesto di Forza Italia con lo slogan: "Onestà, Esperiezna, Saggezza"". Il24.it. Archived from the original on 3 February 2018. Retrieved 4 March 2018.

- "Prima gli italiani, Salvini invita Di Maio: "Vieni alla nostra manifestazione di Milano"". Secoloditalia.it. 23 February 1976. Retrieved 4 March 2018.

- "Con il Governo Salvini, prima gli Italiani". Facebook.com. Retrieved 4 March 2018.

- "Grasso adotta lo slogan di Corbyn: "Per i molti, non per i pochi"". Ilmessaggero.it. Retrieved 4 March 2018.

- "Assemblea Liberi e Uguali: "Sinistra per i molti e non per i pochi", Grasso si ispira a Corbyn". Ilfattoquotidiano.it. Retrieved 4 March 2018.

- "Fratelli d'Italia: Il voto che unisce l'Italia". YouTube.com. Retrieved 4 March 2018.

- "Il voto che unisce l'Italia" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 2 March 2018. Retrieved 27 April 2019.

- "Più Europa – Con Emma Bonino". Facebook.com. 24 February 2018. Retrieved 4 March 2018.

- "Più a Europa, per un'Italia libera e democratica". Piueuropa.eu. Retrieved 4 March 2018.

- "Comitati territoriali "Insieme è meglio!"". Insieme2018.it. Retrieved 4 March 2018.

- "Italia Europa Insieme". Insieme2018.it. Retrieved 4 March 2018.

- "Civica Popolare – Facebook". Facebook.com. Retrieved 4 March 2018.

- "Lorenzin presenta Civica Popolare: serve un vaccino contro l'incapacità e il populismo". Affaritaliani.it. Retrieved 4 March 2018.

- "Le liste di movimento di Potere al Popolo!". Ilmanifesto.it. Retrieved 4 March 2018.

- "Potere al Popolo! – Noi ci stiamo, chi accetta la sfida?". Poterealpopolo.org. 10 February 2018. Retrieved 4 March 2018.

- "Simone Di Stefano – Vota più forte che puoi! Vota CasaPound!". M.youtube.com. Retrieved 4 March 2018.

- "Il 4 Marzo vota più forte che puoi". Facebook.com. Retrieved 4 March 2018.

- "La tv orfana dei faccia a faccia, sarà una campagna elettorale senza duelli". Lastampa.it. 27 February 2018. Retrieved 4 March 2018.

- "Prodi-Berlusconi, duello ad alta tensione". Corriere.it. Retrieved 4 March 2018.

- "Di Maio annulla faccia a faccia con Renzi: non è più lui il leader". Rainews.it. 27 November 2013. Retrieved 4 March 2018.

- "L'intervista a Luigi Di Maio, candidato premier del M5S" (in Italian). La7.it. 16 January 2018. Retrieved 4 March 2018.

- "Porta a Porta – Intervista a Berlusconi". Raiplay.it. Retrieved 4 March 2018.

- "Quinta Colonna – L'intervista a Renzi". Video.mediaset.it. 7 December 2017. Retrieved 4 March 2018.

- Barbara Acquaviti. "Il patto a quattro Pd-Ap-Lega-Fi regge. Primo ok al Rosatellum, ma da martedì in Aula entra nel mirino dei franchi tiratori". Huffingtonpost.it. Retrieved 4 March 2018.

- "Rosatellum approvato alla Camera. Evitata la trappola dello scrutinio segreto. Via libera al salva-Verdini". Repubblica.it. Retrieved 4 March 2018.

- "Il Rosatellum bis è legge dello Stato: via libera definitivo al Senato con 214 sì". Repubblica.it. 26 October 2017. Retrieved 4 March 2018.

- Giuseppe Alberto Falci (10 March 2017). "Rosatellum, come funziona la legge elettorale e cosa prevede". Corriere.it. Retrieved 4 March 2018.

- "Rosatellum 2.0, tutti i rischi del nuovo Patto del Nazareno". Ilsole24ore.com. 21 September 2017. Retrieved 4 March 2018.

- Chughtai, Alia (4 March 2018). "Understanding Italian elections 2018". Al Jazeera. Retrieved 6 March 2018.

- Pregliasco, Lorenzo; Cavallaro, Matteo (15 January 2018). "'Hand-to-hand' combat in Italy's election". Politico. Retrieved 6 March 2018.

- "Elezioni, come si vota con il Rosatellum, debutta la nuova scheda elettorale". Today.it. 20 October 2017. Retrieved 4 March 2018.

- AGI - Agenzia Giornalistica Italia (23 July 2017). "Il Rosatellum bis è legge. Ma come funziona?". Agi.it. Retrieved 4 March 2018.

- "Elezioni, 'Salvini, Berlusconi, Meloni' e il tricolore, il simbolo del centro-destra per l'estero". Affaritaliani.it.

- Binelli, Raffaello. "Salvini vince la sua sfida: eletto anche in Calabria". ilGiornale.it.

- "Ipsos – Elezioni politiche 2018: Analisi post voto" (PDF).

- "Salvini: "La Lega guiderà governo". Di Maio: "Inizia Terza Repubblica"".

- "Renzi: "Lascerò dopo nuovo governo. Pd all'opposizione". Ma è scontro nel partito: "Via subito"". 5 March 2018.

- "Was die Populisten wirklich wollen". Frankfurter Allgemeine Zeitung. 6 March 2018.

- "Italy's Salvini open to coalition with 5Stars". POLITICO. 14 March 2018. Retrieved 8 April 2018.

- (www.dw.com), Deutsche Welle. "Five Star Movement (M5S) courts Democratic Party (PD) for Italian coalition | DW | 7 April 2018". DW.COM. Retrieved 8 April 2018.

- "Italienische Wahlsieger einigen sich auf Parlamentspräsidenten". Der Spiegel. 24 March 2018.

- "Italienische Wahlsieger einigen sich auf Parlamentspräsidenten [1:10]". Südtirol News. 25 March 2018. Archived from the original on 30 March 2018. Retrieved 29 March 2018.

- "Italian president makes fresh push to form government". The Financial Times. 18 April 2018. Retrieved 18 April 2018.

- "Italy Picks New Mediator in Search for Government Majority". Bllomberg. Retrieved 24 April 2018.

- "Fünf-Sterne-Bewegung fordert Neuwahlen". Zeit. Retrieved 30 April 2018.

- "Fünf-Sterne-Bewegung verlangt Neuwahlen". Spiegel Online. Retrieved 30 April 2018.

- "Ratlosigkeit in Rom: Sind Neuwahlen nötig?". OÖNachrichten. Retrieved 2 May 2018.

- "Italian president says 'neutral' government should lead until end of year". The Guardian. 7 May 2018. Retrieved 9 May 2018.

- "Italy's populist parties given 24 hours to avert fresh elections". Financial Times. 9 May 2018. Retrieved 9 May 2018.

- "Governo M5S-Lega, Berlusconi: nessun veto all'intesa ma no alla fiducia" (in Italian). La Repubblica. 9 May 2018. Retrieved 9 May 2018.

- "Italy's populist 5 Star, League parties reach deal on government program". MarketWatch. 13 May 2018.

- "Italian parties agree government program, say no threat to euro". 18 May 2018 – via www.reuters.com.

- "Italy's 5-Star Movement and League publish anti-austerity government programme". France 24. 18 May 2018.

- "Italy awaits PM nominee after populists unveil government programme". www.thelocal.it. 19 May 2018.

- "Italy's 5-star members back coalition program with League in online..." 18 May 2018 – via www.reuters.com.

- "Italy's Populist League Gives Public a Say on Coalition Program". Bloomberg.com. 18 May 2018. Retrieved 26 September 2020.

- "Italians back League, 5-Star plan as groups ready government team". 20 May 2018 – via www.reuters.com.

- "Italy populists name PM candidate". BBC News. 21 May 2018. Retrieved 22 May 2018.

- Giorgio, Massimiliano Di. "Italian president hesitates as novice put forward as premier". U.S. Retrieved 21 May 2018.

- "The Latest: Populists' premier gets presidential mandate". Archived from the original on 24 May 2018. Retrieved 23 May 2018.

- "Di Battista all'attacco di Mattarella: "Non si opponga agli italiani". La lunga giornata del Colle". Repubblica.it. 23 May 2018.

- "Governo, il giorno della rinuncia di Conte. Ecco come è fallita la trattativa su Savona". Repubblica.it. 27 May 2018.

- "L'ora più buia di Mattarella: la scelta obbligata di difendere l'interesse nazionale dopo il no dei partiti alla soluzione Giorgetti per l'Economia". L’Huffington Post. 27 May 2018.

- "Governo, firme e tweet di solidarietà a Mattarella. Ma spuntano anche minacce di morte". Repubblica.it. 27 May 2018.

- "Cottarelli accetta l'incarico: "Senza fiducia il Paese al voto dopo agosto"". Repubblica.it (in Italian). 28 May 2018. Retrieved 28 May 2018.

- Online, Redazione. "Cottarelli accetta di formare il governo: con la fiducia al voto nel 2019, senza dopo agosto". Corriere della Sera (in Italian). Retrieved 29 May 2018.

- "Governo, Mattarella dà l'incarico. Cottarelli: 'Senza fiducia elezioni dopo agosto' - Politica". ANSA.it (in Italian). 28 May 2018. Retrieved 29 May 2018.

- "Berlusconi: "No alla fiducia e centrodestra unito al voto". Ma Salvini: "Alleanza con Fi? Ci penserò"". Repubblica.it (in Italian). 28 May 2018. Retrieved 29 May 2018.

- "Pd, Martina: "Fiducia a Cottarelli". Renzi: "Salviamo il Paese". E i dem: manifestazione nazionale a Roma il 1° giugno". Repubblica.it (in Italian). 28 May 2018. Retrieved 29 May 2018.

- Online, Redazione. "Incontro informale in corso tra Cottarelli e MattarellaI tre scenari possibili". Corriere della Sera (in Italian). Retrieved 30 May 2018.

- "Governo, Cottarelli vede Mattarella. Ora al lavoro alla Camera. Riparte la trattativa giallo-verde". Repubblica.it (in Italian). 30 May 2018. Retrieved 30 May 2018.

- "Di Maio: "Impeachment non-più sul tavolo". E si riapre l'ipotesi di un governo Lega-M5s". Repubblica.it (in Italian). 29 May 2018. Retrieved 30 May 2018.

.jpg.webp)

.jpg.webp)