1992 European Community Monitor Mission helicopter downing

The 1992 European Community Monitor Mission helicopter downing was an incident that occurred on 7 January 1992, during the Croatian War of Independence, in which a European Community Monitor Mission (ECMM) helicopter carrying five European Community (EC) observers was downed by a Yugoslav Air Force Mikoyan-Gurevich MiG-21, in the air space above the village of Podrute, near Novi Marof, Croatia. An Italian and a French officer and three Italian non-commissioned officers were killed. Another ECMM helicopter flying in formation with the attacked helicopter made an emergency landing. The second helicopter carried a crew and a visiting diplomat, all of whom survived. The incident was condemned by the United Nations Security Council and the EC. As a result of the incident, the Yugoslav authorities suspended the head of the air force, and the Yugoslav defense minister, General Veljko Kadijević, resigned his post. The events followed the end of the first stage of the war in Croatia and closely preceded the country's international recognition.

| 1992 European Community Monitor Mission helicopter downing | |

|---|---|

| Part of the Croatian War of Independence | |

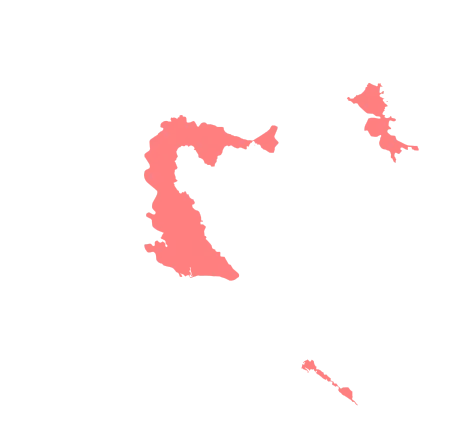

The map of Croatia in January 1992. Serb/JNA-held territories are highlighted in red. | |

| Type | Aircraft shootdown |

| Location | near Podrute, Croatia |

| Objective | |

| Date | 7 January 1992 |

| Executed by | |

| Casualties | 5 European Community observers killed |

The MiG-21 pilot, Lieutenant Emir Šišić, disappeared after the incident. He was tried in absentia together with his superiors by Croatian authorities, convicted, and sentenced to extended imprisonment. Šišić was subsequently arrested in Hungary in 2001 and extradited to Italy, where he was tried, convicted and sentenced to 15 years in prison. In 2006, he was turned over to Serbia for the remainder of the sentence, but released in 2008. Two other Yugoslav officers were tried in absentia in Italy and convicted in 2013, while Serbia was ordered to pay monetary damages to the victims' families. The victims were posthumously decorated by Italy and France, respectively.

Background

In 1990, following the electoral defeat of the government of the Socialist Republic of Croatia, ethnic tensions worsened. The Yugoslav People's Army (Jugoslovenska Narodna Armija – JNA) confiscated Croatia's Territorial Defence (Teritorijalna obrana - TO) weapons to minimize resistance.[1] On 17 August, the tensions escalated into an open revolt by Croatian Serbs,[2] centered on the predominantly Serb-populated areas of the Dalmatian hinterland around Knin,[3] parts of the Lika, Kordun, Banovina and eastern Croatia.[4]

Following the Pakrac clash between Serb insurgents and Croatian special police in March 1991,[5] the conflict had escalated into the Croatian War of Independence.[6] The JNA stepped in, increasingly supporting the Croatian Serb insurgents.[7] In early April, the leaders of the Croatian Serb revolt declared their intention to integrate the area under their control, known as SAO Krajina, with Serbia.[8] In May, the Croatian government responded by forming the Croatian National Guard (Zbor narodne garde - ZNG),[9] but its development was hampered by a United Nations (UN) arms embargo introduced in September.[10] The Brioni Agreement established an observer mission which was eventually called the European Community Monitor Mission (ECMM). The mission was tasked with monitoring the disengagement of belligerents in the Ten-Day War in neighbouring Slovenia,[11] and the withdrawal of the JNA from Slovenia.[12] However, on 16 August, an ECMM helicopter was hit by Croatian Serb gunfire in western Slavonia, injuring one of the pilots.[13] This caused the ECMM's scope of work to be formally expanded to include Croatia on 1 September.[14]

On 8 October, Croatia declared independence from Yugoslavia,[15] and a month later the ZNG was renamed the Croatian Army (Hrvatska vojska - HV).[9] The fiercest fighting of the war occurred around this time, when the 1991 Yugoslav campaign in Croatia culminated in the Siege of Dubrovnik,[16] and the Battle of Vukovar.[17] In November, Croatia, Serbia and the JNA agreed upon the Vance plan entailing a ceasefire, protection of civilians in specific areas designated as United Nations Protected Areas, and the presence of UN peacekeepers in Croatia.[18] The ceasefire came into effect on 3 January 1992.[19] In December 1991, the European Community (EC) announced its decision to grant formal diplomatic recognition to Croatia as of 15 January 1992.[20]

Incident

On 7 January 1992, a pair of Italian Army Agusta-Bell AB-206L LongRanger helicopters operated by ECMM observers entered Croatian air space from Hungary.[21] The helicopters were white-painted and unarmed.[22] They were flying from the Yugoslav capital of Belgrade to Zagreb via Kaposvár, Hungary.[23] Authorities in Belgrade claim the helicopters were authorised to fly to Hungary, but that the pilots were warned they were not allowed to fly to Zagreb because no flights in Croatian airspace were permitted.[24] The EC dismissed those claims, saying that the flight was approved in advance by Yugoslav air controllers.[23] The approval was forwarded to the Yugoslav Air Force operations centre, but the order was never forwarded to the 5th Aviation Corps in Bihać, Bosnia and Herzegovina.[21]

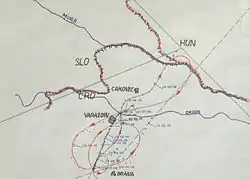

After the two helicopters were spotted by a Yugoslav Air Force tracking radar near Bihać, a pair of Mikoyan-Gurevich MiG-21s, which were on standby at the Željava Air Base near Bihać, were ordered to take off and intercept the aircraft.[24] The MiG-21s, assigned to the 125th Squadron of the 117th Fighter Aviation Regiment,[25] were piloted by Lieutenant Emir Šišić and Captain Danijel Borović.[26] However, Borović declared that his aircraft had a problem with its engine, and Šišić took off alone. Šišić was guided to the incoming helicopters at an altitude of 3,000 metres (9,800 feet), and then ordered to make a full circle with his jet. As he turned around, he spotted the helicopters flying below his plane, at an altitude of 600 metres (2,000 feet). Šišić requested further orders and was told to shoot the helicopters down.[24] The order was issued by the duty officer at the Željava Air Base, Lieutenant Colonel Dobrivoje Opačić.[27]

Šišić pursued the helicopters, firing aircraft gun in front of the helicopters, but his aircraft was not armed with tracer ammunition and the helicopter pilots were not able to observe that they were fired upon. Flying at a speed of 1,000 kilometres per hour (540 knots), he switched to missiles and registered that the missile seekers had acquired the targets.[24] Šišić fired two infrared homing R-60 missiles.[21] One of the missiles flew between the two helicopters, while the other struck the engine of the lead helicopter.[24] The helicopter was shot down near the village of Podrute, located in an area administered by the city of Novi Marof, north of Zagreb.[27] The second helicopter had to crash-land to evade the attack.[23]

Aftermath

Five ECMM observers were killed in the attack, including four Italians and one Frenchman.[23] The victims were Lieutenant Colonel Enzo Venturini, helicopter pilot, Staff Sergeant Marco Matta, co-pilot, Sergeant Major Fiorenzo Ramacci, Sergeant Major Silvano Natale, and Ship-of-the-line Lieutenant Jean-Loup Eychenne.[28] The Italian personnel were drawn from the 5th Army Aviation Regiment "Rigel". The second helicopter carried a diplomat and three Italian ECMM observers, none of whom were harmed.[27] The crash site was toured by the police, ECMM staff and journalists,[29] and EC representatives visited Belgrade to receive a report on the incident from Yugoslav authorities. The action of the Yugoslav Air Force was condemned by the Conference on Security and Co-operation in Europe,[24] the United Nations Security Council,[30] and the EC Council of Ministers. The Italian ambassador to Yugoslavia was recalled to Rome for consultations. Subsequently, Italy cancelled an air traffic agreement with Yugoslavia, causing Jat Airways to cancel Belgrade–Rome flights.[31] In addition, ECMM operations were suspended for several days.[32]

Yugoslav Ministry of Defence announced that it had initiated criminal proceedings against an officer, with four other officers facing military disciplinary action.[23] The commander of the Yugoslav Air Force, Colonel General Zvonko Jurjević was suspended.[33] The federal defense minister, General Veljko Kadijević officially apologized for the incident and resigned his post.[34] Šišić was court-martialled in Belgrade in 1992, and acquitted based on claims that he shot at a ZNG helicopter illegally escorting the two ECMM helicopters.[21] In a 2008 interview, Šišić claimed that the ECMM helicopter crashed after being hit by a fireball caused by the exploding third helicopter.[35] His account is contradicted by crash scene eyewitnesses,[29] as well as Željava Air Base radar data, both of which indicate that only two aircraft were flying to Zagreb.[24]

Šišić and Opačić were tried in absentia in Croatia, and both were convicted and sentenced to 20 years in prison. Borović, who defected to Croatia a month after the attack, testified against Šišić.[21] Šišić was arrested by Hungarian police at the Horgoš–Röszke border crossing on 9 May 2001.[35] His extradition was requested by both Croatia and Italy. He was ultimately extradited to Italy in June 2002, where he was subsequently tried, convicted, and sentenced to 15 years in prison for five counts of homicide and causing an aircraft disaster. In 2006, he was transferred to Serbia for the remainder of the prison term.[21] He was released by Serbian authorities in 2008.

In 2013, the Appeals Court in Rome tried Opačić, General Ljubomir Bajić, commander of the 5th Aviation Corps, and Colonel Božidar Martinović, head of the Yugoslav Air Defence operational centre in Belgrade in absentia for the attack. Opačić and Bajić were convicted and each sentenced to 28 years in prison, while Martinović was acquitted. The court also ordered Serbia to pay compensation to families of those killed in the attack, in the provisional amount of 950,000 Euros.[27] In a 2008 interview, Šišić said he regretted the deaths of the crew but felt no remorse for his actions.[35]

On 25 May 1993, Italy posthumously decorated the four Italian ECMM observers killed in the attack with the Gold Medal of Military Valor, and the surviving three Italians aboard the second helicopter with the Silver Medal of Military Valor.[36] Eychenne was posthumously promoted to lieutenant commander effective 7 January 1992, and attributed Mort pour la France on 14 April of the same year. He was decorated as the Chevalier of the Legion of Honour. The incident is commemorated annually in Podrute and the ceremonies held there are regularly attended by representatives of the Croatian government and military, representatives of Italian and French Armed Forces, along with European Union, French and Italian diplomats.[38]

Footnotes

- Hoare 2010, p. 117.

- Hoare 2010, p. 118.

- The New York Times & 19 August 1990.

- ICTY & 12 June 2007.

- Ramet 2006, pp. 384–385.

- The New York Times & 3 March 1991.

- Hoare 2010, p. 119.

- The New York Times & 2 April 1991.

- EECIS 1999, pp. 272–278.

- The Independent & 10 October 1992.

- Ahrens 2007, p. 43.

- O'Shea 2005, p. 16.

- Mesić 2004, p. 236.

- Miškulin 2010, p. 310.

- Narodne novine & 8 October 1991.

- Bjelajac & Žunec 2009, pp. 249–250.

- The New York Times & 18 November 1991.

- Armatta 2010, pp. 194–196.

- Marijan 2012, p. 103.

- The New York Times & 24 December 1991.

- Nacional & 14 November 2006.

- Ripley 2013, p. 9.

- Los Angeles Times & 12 January 1992.

- Politika & 23 November 2006.

- Jutarnji list & 7 January 2012.

- European Parliament 1992, H-0278/92.

- Novi list & 27 May 2013.

- EUROMIL 2012.

- RFE & 14 May 2008.

- Bethlehem & Weller 1997, p. 3.

- Bellucci & Isernia 2003, p. 215.

- Lucarelli & RSC 1995, p. 20.

- Bethlehem & Weller 1997, p. xxxiii.

- Glaurdić 2011, p. 280.

- Politika & 13 May 2008.

- Gazzetta Ufficiale & 25 May 1993.

- Dubrovački vjesnik & 7 January 2010.

References

- Books and journal articles

- Ahrens, Geert-Hinrich (2007). Diplomacy on the Edge: Containment of Ethnic Conflict and the Minorities Working Group of the Conferences on Yugoslavia. Washington, D.C.: Woodrow Wilson Center Press. ISBN 978-0-8018-8557-0.

- Armatta, Judith (2010). Twilight of Impunity: The War Crimes Trial of Slobodan Milosevic. Durham, North Carolina: Duke University Press. ISBN 978-0-8223-4746-0.

- Bellucci, Paolo; Isernia, Pierangelo (2003). "Massacring in Front of a Blind Audience? Italian Public Opinion and Bosnia". In Sobel, Richard; Shiraev, Eric; Shapiro, Robert (eds.). International Public Opinion and the Bosnia Crisis. Lanham, Maryland: Lexington Books. pp. 173–218. ISBN 978-0-7391-0480-4.

- Bethlehem, Daniel L.; Weller, Marc, eds. (1997). The 'Yugoslav' Crisis in International Law: General Issues, Part 1. Cambridge, England: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-46304-1.

- Bjelajac, Mile; Žunec, Ozren (2009). "The War in Croatia, 1991–1995". In Charles W. Ingrao; Thomas Allan Emmert (eds.). Confronting the Yugoslav Controversies: A Scholars' Initiative. West Lafayette, Indiana: Purdue University Press. pp. 230–271. ISBN 978-1-55753-533-7.

- Eastern Europe and the Commonwealth of Independent States. London, England: Routledge. 1999. ISBN 978-1-85743-058-5.

- Glaurdić, Josip (2011). The Hour of Europe: Western Powers and the Breakup of Yugoslavia. New Haven, Connecticut: Yale University Press. ISBN 978-0-300-16629-3.

- Hoare, Marko Attila (2010). "The War of Yugoslav Succession". In Ramet, Sabrina P. (ed.). Central and Southeast European Politics Since 1989. Cambridge, England: Cambridge University Press. pp. 111–136. ISBN 978-1-139-48750-4.

- Lucarelli, Sonia; Robert Schumann Centre (1995). The International Community and the Yugoslav Crisis: A Chronology of Events. Florence, Italy: European University Institute. OCLC 34091158.

- Marijan, Davor (May 2012). "The Sarajevo Ceasefire – Realism or strategic error by the Croatian leadership?". Review of Croatian History. Croatian Institute of History. 7 (1): 103–123. ISSN 1845-4380.

- Mesić, Stjepan (2004). The Demise of Yugoslavia: A Political Memoir. Budapest, Hungary: Central European University Press. ISBN 978-963-9241-81-7.

- Miškulin, Ivica (October 2010). ""Sladoled i sunce" – Promatračka misija Europske zajednice i Hrvatska, 1991.–1995" ["Ice cream and sun" – European Community Monitor Mission and Croatia, 1991–1995]. Journal of Contemporary History (in Croatian). Croatian Institute of History. 42 (2): 299–337. ISSN 0590-9597.

- O'Shea, Brendan (2005). The Modern Yugoslave Conflict 1991–1995: Perception, Deception and Dishonesty. London, England: Routledge. ISBN 978-0-415-35705-0.

- Ramet, Sabrina P. (2006). The Three Yugoslavias: State-Building And Legitimation, 1918–2006. Bloomington, Indiana: Indiana University Press. ISBN 978-0-253-34656-8.

- Ripley, Tim (2013). Conflict in the Balkans 1991–2000. Oxford, England: Osprey Publishing. ISBN 978-1-4728-0383-2.

- News reports

- Barbir-Mladinović, Ankica; Nikolić, Maja; Preradović, Zoran (14 May 2008). "Slučaj Šišić ponovo uzburkao javnost" [Šišić Case Stirs Public Again] (in Bosnian). Radio Free Europe/Radio Liberty.

- Bellamy, Christopher (10 October 1992). "Croatia built 'web of contacts' to evade weapons embargo". The Independent.

- Brnčić, Šarlota (27 May 2013). "Dužnosnicima JNA po 28 godina za rušenje helikoptera EEZ-a" [JNA Officials Sentenced to 28 Years Each for EEC Helicopter Shootdown]. Novi list (in Croatian).

- "EC Rejects Yugoslav Version of Copter Downing". Los Angeles Times. Reuters. 12 January 1992.

- Engelberg, Stephen (3 March 1991). "Belgrade Sends Troops to Croatia Town". The New York Times.

- Galović, Milan (26 November 2006). "Raketa pogodila motor" [Rocket Struck Engine]. Politika (in Serbian).

- Kinzer, Stephen (24 December 1991). "Slovenia and Croatia Get Bonn's Nod". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 29 July 2012.

- Pašalić, Davor (14 November 2006). "Srpski pilot ubojica pred pomilovanjem" [Serbian Killer Pilot Awaits Pardon]. Nacional (weekly) (in Croatian). Archived from the original on 22 August 2013. Retrieved 9 January 2012.

- "Roads Sealed as Yugoslav Unrest Mounts". The New York Times. Reuters. 19 August 1990.

- Špac, Luka (7 January 2012). "Kako su 1992. poginuli promatrači Europske zajednice. 'Pilotu jugoslavenskog MIG-a 21 časnik je naredio: Oderi ga!'" [How Did the European Community Monitors Die in 1992: An Officer Ordered Yugoslav MiG-21 Pilot: Whack him!]. Jutarnji list (in Croatian).

- Špac, Luka (7 January 2010). "Komemoracija za promatrače EZ poginule 1992" [Commemoration for the EC Observers Killed in 1992]. Dubrovački vjesnik (in Croatian). Archived from the original on 4 October 2013. Retrieved 4 October 2013.

- Sudetic, Chuck (18 November 1991). "Croats Concede Danube Town's Loss". The New York Times.

- Sudetic, Chuck (2 April 1991). "Rebel Serbs Complicate Rift on Yugoslav Unity". The New York Times.

- Vukosavljević, Danijela (13 May 2008). "Šišić: Žalim zbog poginulih u helikopteru" [Šišić: I Regret Deaths of the Helicopter Crew]. Politika (in Serbian).

- Other sources

- "20th anniversary of the European Community Monitor Mission helicopter downing". EUROMIL. 2012.

- "Biographie du lieutenant de vaisseau Jean Loup Eychenne" [Biography of the Ship-of-the-line Lieutenant Jean Loup Eychenne] (in French). Marine nationale (French Navy). 13 January 2012.

- "Odluka" [Decision]. Narodne novine (in Croatian). Narodne novine d.d. (53). 8 October 1991. ISSN 1333-9273. Archived from the original on 23 September 2009.

- Official Journal of the European Communities: Debates of the European Parliament, Issues 417-418. Luxembourg: Office for Official Publications of the European Communities. 1992.

- "Ricompense al valor militare" [Awards for Valour] (in Italian). Gazzetta Ufficiale. 25 May 1993. Archived from the original on 3 March 2012. Retrieved 9 January 2012.

- "The Prosecutor vs. Milan Martic – Judgement" (PDF). International Criminal Tribunal for the former Yugoslavia. 12 June 2007.