7 March Speech of Bangabandhu

The 7 March Speech of Bangabandhu was a speech given by Sheikh Mujibur Rahman, the founding father of Bangladesh on 7 March 1971 at the Ramna Race Course in Dhaka to a gathering of over 10 lac people. It was delivered during a period of escalating tensions between East Pakistan and the powerful political and military establishment of West Pakistan, this was filmed by the actor. In the speech, Rahman proclaimed: "This time the struggle is for our freedom. This time the struggle is for our independence." He announced a civil disobedience movement in the province, calling for "every house to turn into a fortress". The speech inspired the Bengali people to prepare for a war of independence amid widespread reports of armed mobilisation by West Pakistan. The Bangladesh Liberation War began 18 days later when the Pakistan Army launched Operation Searchlight against Bengali civilians, intelligentsia, students, politicians, and armed personnel. On 30 October 2017, UNESCO added the speech in the Memory of the World Register as a documentary heritage.[1][2]

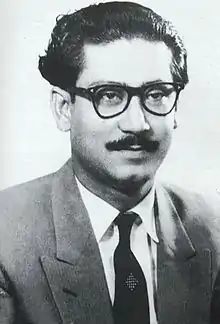

Sheikh Mujibur Rahman delivering his speech on 7 March 1971 | |

| Native name | বঙ্গবন্ধুর ৭ই মার্চের ভাষণ |

|---|---|

| Date | March 7, 1971 |

| Time | 2:45 pm — 3:03 pm |

| Duration | Approximately 19 Minutes |

| Venue | Race Course (Race Course Moydan in native language) |

| Location | Ramna, Dhaka, East Pakistan |

| Coordinates | 23.7331°N 90.3984°E |

| Type | Speech |

| Theme | Independence of Bangladesh |

| Filmed by | Abul Khair |

Background

Pakistan was created in 1947, during the Partition of India, as a Muslim homeland in South Asia. Its territory comprised most of the Muslim-majority provinces of British India, including two geographically and culturally separate areas, one east of India and the other west. The western zone was popularly (and, for a period, officially) called West Pakistan; the eastern zone (modern-day Bangladesh) was called East Bengal and then East Pakistan. West Pakistan dominated the country politically, and its leaders exploited the East economically, leading to popular grievances.

When East Pakistanis, such as Khawaja Nazimuddin, Muhammad Ali Bogra, and Huseyn Shaheed Suhrawardy, were elected Prime Minister of Pakistan, they were swiftly deposed by the predominantly West Pakistani establishment. The military dictatorships of Ayub Khan (27 October 1958 – 25 March 1969) and Yahya Khan (25 March 1969 – 20 December 1971), both West Pakistanis, worsened East Pakistanis' discontent.

In 1966, the Awami League, led by Sheikh Mujib, launched the Six Point Movement to demand provincial autonomy for East Pakistan. The Pakistani establishment rejected the league's proposals, and the military government arrested Sheikh Mujib and charged him with treason in the Agartala Conspiracy Case. After three years in jail, Mujib was released in 1969, and the case against him was dropped in the face of mass protests and widespread violence in East Pakistan.

In 1970, the Awami League, the largest East Pakistani political party, won a landslide victory in national elections, winning 167 of the 169 seats allotted to East Pakistan and a majority of the 313 seats in the National Assembly. This gave it the constitutional right to form a government. However, Zulfikar Ali Bhutto, the leader of the Pakistan Peoples Party and a member of the Sindhi ethnic group, refused to allow Sheikh Mujib to become prime minister. Instead, he proposed having two prime ministers, one for each wing.

Negotiations began in Dhaka between the two sides. In January 1971, after the first round of negotiations, President Yahya Khan promised in the Dhaka airport that Sheikh Mujib would be the next prime minister and that the newly elected National Assembly would convene on 3 March 1971. However, Bhutto was vehemently opposed to a Bengali becoming prime minister, and he began a campaign of racially charged speeches across West Pakistan to invoke fear of Bengali domination. He warned West Pakistani MPs-elect not to travel to the East. Fearing a civil war, Bhutto secretly sent an associate, Mubashir Hassan, to meet with Sheikh Mujib and members of his inner circle. It was decided that Sheikh Mujib would serve as prime minister, with Bhutto as president. These talks were kept hidden from the public and from the armed forces. Meanwhile, Bhutto pressured Yahya Khan to take a stance.

On 3 March, the convening of the National Assembly was postponed until 25 March, leading to an outcry across East Pakistan. Violence broke out in Dhaka, Chittagong, Rangpur, Comilla, Rajshahi, Sylhet, and Khulna, and the security forces killed dozens of unarmed protesters. There were open calls for Sheikh Mujib to declare independence from Pakistan, and the Awami League called a large public gathering at Dhaka's Ramna Race Course on 7 March to respond.

Recording

The Pakistan government didn't give permission to live broadcast the speech through radio and television on 7 March 1971. AHM Salahuddin who was the then chairman of Pakistan International Film Corporation and M Abul Khayer, a then member of the National Assembly from East Pakistan, made arrangements to record the video and audio of the speech. The video was recorded by actor Abul Khair who was the Director of Films under Ministry of Information of Pakistan at the time. The audio of the speech was recorded by HN Khondokar, a technician of the Ministry of Information.[3]

The audio record was developed and archived by Dhaka Record, a record label owned by M Abul Khayer. Later on, copy of the audio and video recording was handed over to Sheikh Mujib and a copy of the audio was sent to India. 3000 copies of the audio were distributed by Indian record label HMV Records throughout the world.[3]

The speech

Bangabandhu started with the lines, "Today, I appeared before you with a heavy heart. You know everything and understand as well. We tried with our lives. But the painful matter is that today, in Dhaka, Chattogram, Khulna, Rajshahi and Rangpur, the streets are dyed red with the blood of our brethren. Today the people of Bengal want freedom, the people of Bengal want to survive, the people of Bengal want to have their rights. What wrong did we do?"

He mentioned four conditions for joining the National Assembly on 25 March:

- The immediate lifting of martial law;

- The immediate withdrawal of all military personnel to their barracks;

- The immediate transfer of power to elected representatives of the people;

- A proper inquiry into the loss of life during the conflict.

He also gave several directives for a civil disobedience movement, instructing that:

- People should not pay taxes;

- Government servants should take orders only from him;

- The secretariat, government and semi-government offices, and courts in East Pakistan should observe strikes, with necessary exemptions announced from time to time;

- Only local and inter-district telephone lines should function;

- Railways and ports could continue to function, but their workers should not co-operate if they were used to repress the people of East Pakistan.

The speech lasted about 19 minutes and concluded with, "Our struggle, this time, is a struggle for our freedom. Our struggle, this time, is a struggle for our independence. Joy Bangla!"[4][5] It was a de facto declaration of Bangladesh's independence.[6]

International media had descended upon East Pakistan for the speech amidst speculation that Sheikh Mujib would make a unilateral declaration of independence from Pakistan. However, keeping in mind the failures of Rhodesia's Unilateral Declaration of Independence and of the Biafra struggle in Nigeria, he did not make a direct declaration. Nevertheless, the speech was effective in giving Bengalis a clear goal of independence.[7]

Recognition from UNESCO

The speech is on the Memory of the World Register of UNESCO, a list of world's important documentary heritage.[2] Irina Bokova, Director General of UNESCO announced the decision at its headquarters in Paris on 30 October 2017.[8]

Legacy

- The documentary film Muktir Gaan, by Tareque Masud and Catherine Masud, begins with a video of the speech.

- The novelist and columnist Anisul Hoque incorporated the speech into his historical novel Maa, published in 2004.

- In his novel The Black Coat, Bangladeshi-Canadian author Neamat Imam created a character called Nur Hussain who memorised the speech during the Bangladesh famine of 1974.

- Ziaur Rahman (later President of Bangladesh) wrote in the magazine Bichittra on 26 March 1974 that the speech had inspired him to take part in the 1971 Liberation War.[9][10]

- The speech was included in the book We Shall Fight on the Beaches: The Speeches That Inspired History, by Jacob F. Field.[11]

- The speech was added in the fifth schedule of Constitution of Bangladesh through fifteenth amendment.[12]

References

- "Unesco recognises Bangabandhu's 7th March speech". The Daily Star. 31 October 2017. Retrieved 31 October 2017.

- "International Advisory Committee recommends 78 new nominations on the UNESCO Memory of the World International Register". UNESCO. Retrieved 30 October 2017.

- ঐতিহাসিক সাতই মার্চের ভাষণ ধারণ করেছিলেন আবুল খায়ের. priyo.com (in Bengali). Retrieved 16 November 2018.

- Srivastava, Prabhat (1 January 1972). The Discovery of Bangla Desh. Sanjay Publications. p. 105.

- Guhathakurta, Meghna; Schendel, Willem van (22 March 2013). The Bangladesh Reader: History, Culture, Politics. Duke University Press. p. 219. ISBN 9780822395676.

- Furtado, Peter (1 November 2011). History's Daybook: A History of the World in 366 Quotations. Atlantic Books. ISBN 9780857899279.

- "March 1971: The emergence of a sovereign Bangladesh". Dhaka Tribune. Retrieved 18 April 2016.

- "'Unesco's 7th March speech recognition another milestone'". The Daily Star. 1 November 2017. Retrieved 5 November 2017.

- "৭ই মার্চের রেসকোর্স ময়দানে বঙ্গবন্ধুর ঐতিহাসিক ঘোষণা আমাদের উদ্বুদ্ধ করেছিল তাই আমরা আমাদের পরিকল্পনাকে চূড়ান্ত রূপ দিলাম।" Bichitra, 1974

- "March 7 speech inspired Zia". bdnews24.com.

- "Historic Mar 7 speech recognised as one of the 'world's all-time best'". bdnews24.com.

- Jubaer Ahmed (14 November 2017). "7th March speech and Preamble of our Constitution". The Daily Star. Retrieved 10 November 2020.