Two-nation theory

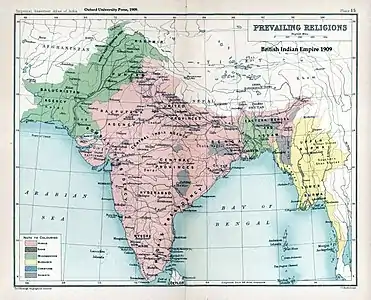

The two-nation theory is an ideology of religious nationalism which significantly influenced the Indian subcontinent following its independence from the British Empire. According to this theory, Muslims and Hindus are two separate nations, with their own customs, religion, and traditions; therefore, from social and moral points of view, Muslims should be able to have their own separate homeland outside of Hindu-majority India, in which Islam is the dominant religion, and be segregated from Hindus and other non-Muslims.[1][2] The two-nation theory advocated by the All India Muslim League is the founding principle of the Pakistan Movement (i.e. the ideology of Pakistan as a Muslim nation-state in the northwestern and eastern regions of India) through the partition of India in 1947.[3]

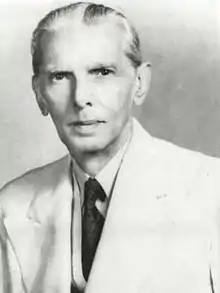

The ideology that religion is the determining factor in defining the nationality of Indian Muslims was undertaken by Muhammad Ali Jinnah, who termed it as the awakening of Muslims for the creation of Pakistan.[4] It is also a source of inspiration to several Hindu nationalist organisations, with causes as varied as the redefinition of Indian Muslims as non-Indian foreigners and second-class citizens in India, the expulsion of all Muslims from India, the establishment of a legally Hindu state in India (which is currently secular), prohibition of conversions to Islam, and the promotion of conversions or reconversions of Indian Muslims to Hinduism.[5][6][7][8]

There are varying interpretations of the two-nation theory, based on whether the two postulated nationalities can coexist in one territory or not, with radically different implications. One interpretation argued for the secession of the Muslim-majority areas of colonial India and saw differences between Hindus and Muslims as irreconcilable; this interpretation nevertheless promised a democratic state where Muslims and non-Muslims would be treated equally.[9] A different interpretation holds that a transfer of populations (i.e. the total removal of Hindus from Muslim-majority areas and the total removal of Muslims from Hindu-majority areas) is a desirable step towards a complete separation of two incompatible nations that "cannot coexist in a harmonious relationship".[10][11]

Opposition to the two-nation theory came from both nationalist Muslims and Hindus, being based on two concepts.[12][13] The first is the concept of a single Indian nation, of which Hindus and Muslims are two intertwined communities.[14] The second source of opposition is the concept that while Indians are not one nation, neither are the Muslims or Hindus of India, and it is instead the relatively homogeneous provincial units of the Indian subcontinent which are true nations and deserving of sovereignty; this view has been presented by the Baloch,[15] Sindhi,[16] Bengali,[17] and Pashtun[18] sub-nationalities of Pakistan, with Bengalis seceding from Pakistan after the Bangladesh Liberation War in 1971 and other separatist movements in Pakistan are currently in-place.[17][19]

The state of India officially rejected the two-nation theory and chose to be a secular state, enshrining the concepts of religious pluralism and composite nationalism in its constitution;[20][13] however, in response to the separatist tendencies of the All India Muslim League, many Hindu nationalist organisations worked to give Hinduism a privileged position within the country.[5][6][7][8]

History

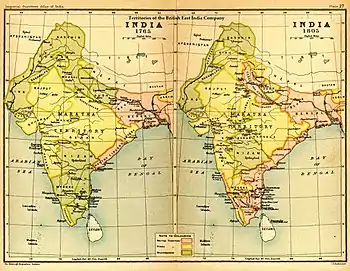

In general, the British-run government and British commentators made "it a point of speaking of Indians as the people of India and avoid speaking of an Indian nation."[2] This was cited as a key reason for British control of the country: since Indians were not a nation, they were not capable of national self-government.[21] While some Indian leaders insisted that Indians were one nation, others agreed that Indians were not yet a nation but there was "no reason why in the course of time they should not grow into a nation."[2] Scholars note that a national consciousness has always been present in "India", or more broadly the Indian subcontinent, even if it was not articulated in modern terms.[22] Historians such as Shashi Tharoor maintain that Britain's divide-and-rule policy aimed at dividing Hindus and Muslims after they united together to fight the British in the Indian Rebellion of 1857.[23]

Similar debates on national identity existed within India at the linguistic, provincial and religious levels. While some argued that Indian Muslims were one nation, others argued they were not. Some, such as Liaquat Ali Khan (later Prime Minister of Pakistan) argued that Indian Muslims were not yet a nation, but could be forged into one.[2]

According to the Pakistan's government official chronology,[24] Muhammad bin Qasim is often referred to as the first Pakistani.[25] While Prakash K. Singh attributes the arrival of Muhammad bin Qasim as the first step towards the creation of Pakistan.[26] Muhammad Ali Jinnah considered the Pakistan movement to have started when the first Muslim put a foot in the Gateway of Islam.[27][28]

Roots of Islamic separatism in Colonial India (17th century–1940s)

In colonial India, many Muslims saw themselves as Indian nationals along with Indians of other faiths.[29][12] These Muslims regarded India as their permanent home, having lived there for centuries, and believed India to be a multireligious entity with a legacy of a joint history and coexistence.[12] The congressman Mian Fayyazuddin stated:

We are all Indians, and participate in the same Indian-ness. We are equal participants, so we want nothing short of equal share. Forget minority and majority, these are the creations of politicians to gain political mileage.[29]

Others, however, started to argue that Muslims were their own nation. It is generally believed in Pakistan that the movement for Muslim self-awakening and identity was started by Ahmad Sirhindi (1564–1624), who fought against emperor Akbar's religious syncretist Din-i Ilahi movement and is thus considered "for contemporary official Pakistani historians" to be the founder of the Two-nation theory,[30] and was particularly intensified under the Muslim reformer Shah Waliullah (1703-1762) who, because he wanted to give back to Muslims their self-consciousness during the decline of the Mughal empire and the rise of the non-Muslim powers like the Marathas, Jats and Sikhs, launched a mass-movement of the religious education which made "them conscious of their distinct nationhood which in turn culminated in the form of Two Nation Theory and ultimately the creation of Pakistan."[31]

Akbar Ahmed also considers Haji Shariatullah (1781–1840) and Syed Ahmad Barelvi (1786–1831) to be the forerunners of the Pakistan movement, because of their purist and militant reformist movements targeting the Muslim masses, saying that "reformers like Waliullah, Barelvi and Shariatullah were not demanding a Pakistan in the modern sense of nationhood. They were, however, instrumental in creating an awareness of the crisis looming for the Muslims and the need to create their own political organization. What Sir Sayyed did was to provide a modern idiom in which to express the quest for Islamic identity."[32]

Thus, many Pakistanis describe modernist and reformist scholar Syed Ahmad Khan (1817–1898) as the architect of the two-nation theory. For instance, Sir Syed, in a January 1883 speech in Patna, talked of two different nations, even if his own approach was conciliatory:

Friends, in India there live two prominent nations which are distinguished by the names of Hindus and Mussulmans. Just as a man has some principal organs, similarly these two nations are like the principal limbs of India.[33]

However, the formation of the Indian National Congress was seen politically threatening and he dispensed with composite Indian nationalism. In an 1887 speech, he said:

Now suppose that all the English were to leave India—then who would be rulers of India? Is it possible that under these circumstances two nations, Mohammedan and Hindu, could sit on the same throne and remain equal in power? Most certainly not. It is necessary that one of them should conquer the other and thrust it down. To hope that both could remain equal is to desire the impossible and inconceivable.[34]

In 1888, in a critical assessment of the Indian National Congress, which promoted composite nationalism among all the castes and creeds of colonial India, he also considered Muslims to be a separate nationality among many others:

The aims and objects of the Indian National Congress are based upon an ignorance of history and present-day politics; they do not take into consideration that India is inhabited by different nationalities: they presuppose that the Muslims, the Marathas, the Brahmins, the Kshatriyas, the Banias, the Sudras, the Sikhs, the Bengalis, the Madrasis, and the Peshawaris can all be treated alike and all of them belong to the same nation. The Congress thinks that they profess the same religion, that they speak the same language, that their way of life and customs are the same... I consider the experiment which the Indian National Congress wants to make fraught with dangers and suffering for all the nationalities of India, especially for the Muslims.[35]

In 1925, during the Aligarh session of the All-India Muslim League, which he chaired, Justice Abdur Rahim (1867–1952) was one of the first to openly articulate on how Muslims and Hindu constitute two nations, and while it would become common rhetoric, later on, the historian S. M. Ikram says that it "created quite a sensation in the twenties":

The Hindus and Muslims are not two religious sects like the Protestants and Catholics of England, but form two distinct communities of peoples, and so they regard themselves. Their respective attitude towards life, distinctive culture, civilization and social habits, their traditions and history, no less than their religion, divide them so completely that the fact that they have lived in the same country for nearly 1,000 years has contributed hardly anything to their fusion into a nation... Any of us Indian Muslims travelling for instance in Afghanistan, Persia, and Central Asia, among Chinese Muslims, Arabs, and Turks, would at once be made at home and would not find anything to which we are not accustomed. On the contrary in India, we find ourselves in all social matters total aliens when we cross the street and enter that part of the town where our Hindu fellow townsmen live.[36]

More substantially and influentially than Justice Rahim, or the historiography of British administrators, the poet-philosopher Muhammad Iqbal (1877–1938) provided the philosophical exposition and Barrister Muhammad Ali Jinnah (1871–1948) translated it into the political reality of a nation-state.[37] Allama Iqbal's presidential address to the Muslim League on 29 December 1930 is seen by some as the first exposition of the two-nation theory in support of what would ultimately become Pakistan.[37]

The All-India Muslim League, in attempting to represent Indian Muslims, felt that the Muslims of the subcontinent were a distinct and separate nation from the Hindus. At first they demanded separate electorates, but when they opined that Muslims would not be safe in a Hindu-dominated India, they began to demand a separate state. The League demanded self-determination for Muslim-majority areas in the form of a sovereign state promising minorities equal rights and safeguards in these Muslim majority areas.[37]

Many scholars argue that the creation of Pakistan through the partition of India was orchestrated by an elite class of Muslims in colonial India, not the common man.[38][39][12] A large number of Islamic political parties, religious schools, and organizations opposed the partition of India and advocated a composite nationalism of all the people of the country in opposition to British rule (especially the All India Azad Muslim Conference).[29]

In 1941, a CID report states that thousands of Muslim weavers under the banner of Momin Conference and coming from Bihar and Eastern U.P. descended in Delhi demonstrating against the proposed two-nation theory. A gathering of more than fifty thousand people from an unorganized sector was not usual at that time, so its importance should be duly recognized. The non-ashraf Muslims constituting a majority of Indian Muslims were opposed to partition but sadly they were not heard. They were firm believers of Islam yet they were opposed to Pakistan.[29]

On the other hand, Ian Copland, in his book discussing the end of the British rule in the Indian subcontinent, precises that it was not an élite-driven movement alone, who are said to have birthed separatism "as a defence against the threats posed to their social position by the introduction of representative government and competitive recruitment to the public service", but that the Muslim masses participated into it massively because of the religious polarization which had been created by Hindu revivalism towards the last quarter of the 19th century, especially with the openly anti-Islamic Arya Samaj and the whole cow protection movement, and "the fact that some of the loudest spokesmen for the Hindu cause and some of the biggest donors to the Arya Samaj and the cow protection movement came from the Hindu merchant and money lending communities, the principal agents of lower-class Muslim economic dependency, reinforced this sense of insecurity", and, because of Muslim resistance, "each year brought new riots" so that "by the end of the century, Hindu-Muslim relations had become so soured by this deadly roundabout of blood-letting, grief and revenge that it would have taken a mighty concerted effort by the leaders of the two communities to repair the breach."[40]

Relevant Opinions

The theory asserted that India was not a nation. It also asserted that Hindus and Muslims of the Indian subcontinent were each a nation, despite great variations in language, culture and ethnicity within each of those groups.[41] To counter critics who said that a community of radically varying ethnics and languages who were territorially intertwined with other communities could not be a nation, the theory said that the concept of nation in the East was different from that in the West. In the East, religion was "a complete social order which affects all the activities in life" and "where the allegiance of people is divided on the basis of religion, the idea of territorial nationalism has never succeeded."[42][43]

It asserted that "a Muslim of one country has far more sympathies with a Muslim living in another country than with a non-Muslim living in the same country."[42] Therefore, "the conception of Indian Muslims as a nation may not be ethnically correct, but socially it is correct."[43]

Muhammad Iqbal had also championed the notion of pan-Islamic nationhood (see: Ummah) and strongly condemned the concept of a territory-based nation as anti-Islamic: "In tāzah xudā'ōⁿ mēⁿ, baṙā sab sē; waṭan hai: Jō pairahan is kā hai; woh maẕhab kā, kafan hai... (Of all these new [false] gods, the biggest; is the motherland (waṭan): Its garment; is [actually] the death-shroud, of religion...)"[44] He had stated the dissolution of ethnic nationalities into a unified Muslim society (or millat) as the ultimate goal: "Butān-e raⁿŋg ō-xūⁿ kō tōṙ kar millat mēⁿ gum hō jā; Nah Tūrānī rahē bāqī, nah Īrānī, nah Afġānī (Destroy the idols of color and blood ties, and merge into the Muslim society; Let no Turanians remain, neither Iranians, nor Afghans)".[45]

Pakistan, or The Partition of India (1945)

In his 1945 book Pakistan, or The Partition of India, Indian statesman and Buddhist Bhimrao Ramji Ambedkar wrote a sub-chapter titled "If Muslims truly and deeply desire Pakistan, their choice ought to be accepted". He asserted that, if the Muslims were bent on the creation of Pakistan, the demand should be conceded in the interest of the safety of India. He asks whether Muslims in the army could be trusted to defend India in the event of Muslims invading India or in the case of a Muslim rebellion. "[W]hom would the Indian Muslims in the army side with?" he questioned. According to him, the assumption that Hindus and Muslims could live under one state if they were distinct nations was but "an empty sermon, a mad project, to which no sane man would agree".[46] In direct relation to the two-nation theory, he notably says in the book:

The real explanation of this failure of Hindu-Muslim unity lies in the failure to realize that what stands between the Hindus and Muslims is not a mere matter of difference and that this antagonism is not to be attributed to material causes. It is formed by causes which take their origin in historical, religious, cultural and social antipathy, of which political antipathy is only a reflection. These form one deep river of discontent which, being regularly fed by these sources, keeps on mounting to a head and overflowing its ordinary channels. Any current of water flowing from another source, however pure, when it joins it, instead of altering the colour or diluting its strength becomes lost in the mainstream. The silt of this antagonism which this current has deposited has become permanent and deep. So long as this silt keeps on accumulating and so long as this antagonism lasts, it is unnatural to expect this antipathy between Hindus and Muslims to give place to unity.[47]

Explanations by Muslim leaders advocating separatism

Muhammad Iqbal's statement explaining the attitude of Muslim delegates to the London round-table conference issued in December 1933 was a rejoinder to Jawaharlal Nehru's statement. Nehru had said that the attitude of the Muslim delegation was based on "reactionarism". Iqbal concluded his rejoinder with:

In conclusion, I must put a straight question to Pandit Jawaharlal, how is India's problem to be solved if the majority community will neither concede the minimum safeguards necessary for the protection of a minority of 80 million people nor accept the award of a third party; but continue to talk of a kind of nationalism which works out only to its own benefit? This position can admit of only two alternatives. Either the Indian majority community will have to accept for itself the permanent position of an agent of British imperialism in the East, or the country will have to be redistributed on a basis of religious, historical and cultural affinities so as to do away with the question of electorates and the communal problem in its present form.

— [48]

In Muhammad Ali Jinnah's All India Muslim League presidential address delivered in Lahore, on March 22, 1940, he explained:

It is extremely difficult to appreciate why our Hindu friends fail to understand the real nature of Islam and Hinduism. They are not religions in the strict sense of the word, but are, in fact, different and distinct social orders, and it is a dream that the Hindus and Muslims can ever evolve a common nationality, and this misconception of one Indian nation has troubles and will lead India to destruction if we fail to revise our notions in time. The Hindus and Muslims belong to two different religious philosophies, social customs, litterateurs. They neither intermarry nor interdine together and, indeed, they belong to two different civilizations which are based mainly on conflicting ideas and conceptions. Their aspect on life and of life are different. It is quite clear that Hindus and Mussalmans derive their inspiration from different sources of history. They have different epics, different heroes, and different episodes. Very often the hero of one is a foe of the other and, likewise, their victories and defeats overlap. To yoke together two such nations under a single state, one as a numerical minority and the other as a majority, must lead to growing discontent and final destruction of any fabric that may be so built for the government of such a state.

— [49]

In 1944, Jinnah said:

We maintain and hold that Muslims and Hindus are two major nations by any definition or test of a nation. We are a nation of hundred million and what is more, we are a nation with our own distinctive culture and civilization, language and literature, art and architecture, names and nomenclature, sense of values and proportions, legal laws and moral codes, customs and calendar, history and tradition, and aptitude and ambitions. In short, we have our own outlook on life and of life.

In an interview with the British journalist Beverley Nichols, he said in 1943:

Islam is not only a religious doctrine but also a realistic code of conduct in terms of every day and everything important in life: our history, our laws and our jurisprudence. In all these things, our outlook is not only fundamentally different but also opposed to Hindus. There is nothing in life that links us together. Our names, clothes, food, festivals, and rituals, all are different. Our economic life, our educational ideas, treatment of women, attitude towards animals, and humanitarian considerations, all are very different.

In May 1947, he took an entirely different approach when he told Mountbatten, who was in charge of British India's transition to independence:

Your Excellency doesn't understand that the Punjab is a nation. Bengal is a nation. A man is a Punjabi or a Bengali first before he is a Hindu or a Muslim. If you give us those provinces you must, under no condition, partition them. You will destroy their viability and cause endless bloodshed and trouble.

Mountbatten replied:

Yes, of course. A man is not only a Punjabi or a Bengali before he is a Muslim or Hindu, but he is an Indian before all else. What you're saying is the perfect, absolute answer I've been looking for. You've presented me the arguments to keep India united.

Support of Ahmadis and some Barelvis

The Ahmadiyya Muslim Jama'at staunchly supported Jinnah and his two-nation theory.[51] Chaudary Zafarullah Khan, an Ahmadi leader, drafted the Lahore Resolution that separatist leaders interpreted as calling for the creation of Pakistan.[52] Chaudary Zafarullah Khan was asked by Jinnah to represent the Muslim League to the Radcliffe Commission, which was charged with drawing the line between an independent India and newly created Pakistan.[52] Ahmadis argued to try to ensure that the city of Qadian, India would fall into the newly created state of Pakistan, though they were unsuccessful in doing so [53] Upon the creation of Pakistan, many Ahmadis held prominent posts in government positions;[52] in the Indo-Pakistani War of 1947–1948, in which Pakistan tried to capture the state of Jammu and Kashmir, the Ahmadiyya Muslim Jama'at created the Furqan Force to fight Indian troops.[54]

Some Barelvi scholars supported the Muslim League and Pakistan's demand, arguing that befriending 'unbelievers' was forbidden in Islam.[55] Other Barelvi scholars strongly opposed the partition of India and the League's demand to be seen as the only representative of Indian Muslims.[56]

Savarkar's ideas on "two nations"

According to Ambedkar, Savarkar's idea of "two nations" did not translate into two separate countries. B. R. Ambedkar summarised Savarkar's position thus:

Mr. Savarkar... insists that, although there are two nations in India, India shall not be divided into two parts, one for Muslims and the other for the Hindus; that the two nations shall dwell in one country and shall live under the mantle of one single constitution;... In the struggle for political power between the two nations the rule of the game which Mr. Savarkar prescribes is to be one man one vote, be the man Hindu or Muslim. In his scheme a Muslim is to have no advantage which a Hindu does not have. Minority is to be no justification for privilege and majority is to be no ground for penalty. The State will guarantee the Muslims any defined measure of political power in the form of Muslim religion and Muslim culture. But the State will not guarantee secured seats in the Legislature or in the Administration and, if such guarantee is insisted upon by the Muslims, such guaranteed quota is not to exceed their proportion to the general population.[46]

But Ambedkar also expressed his surprise at the agreement between Savarkar and Jinnah on describing Hindus and Muslims as two nations. He noticed that both were different in implementation:

"Strange as it may appear, Mr. Savarkar and Mr. Jinnah, instead of being opposed to each other on the one nation versus two nations issue, are in complete agreement about it. Both agree, not only agree but insist, that there are two nations in India —one the Muslim nation and the other the Hindu nation. They differ only as regards the terms and conditions on which the two nations should live. Mr. Jinnah says India should be cut up into two, Pakistan and Hindustan, the Muslim nation to occupy Pakistan and the Hindu nation to occupy Hindustan. Mr. Savarkar, on the other hand, insists that, although there are two nations in India, India shall not be divided into two parts, one for Muslims and the other for the Hindus; that the two nations shall dwell in one country and shall live under the mantle of one single constitution; that the constitution shall be such that the Hindu nation will be enabled to occupy a predominant position that is due to it and the Muslim nation made to live in the position of subordinate co-operation with the Hindu nation."[57]

Opposition to the partition of India

All India Azad Muslim Conference

The All India Azad Muslim Conference, which represented nationalist Muslims, gathered in Delhi in April 1940 to voice its support for an independent and united India.[58] The British, however, sidelined this nationalist Muslim organization and came to see Jinnah, who advocated separatism, as the sole representative of Indian Muslims.[59]

Khan Abdul Ghaffar Khan and the Khudai Khidmatgar

Khan Abdul Ghaffar Khan, also known as the "Frontier Gandhi" or "Sarhadi Gandhi", was not convinced by the two-nation theory and wanted a single united India as a home for both Hindus and Muslims. He was from the North West Frontier Province of British India, now in present-day Pakistan. He believed that the partition would be harmful to the Muslims of the Indian subcontinent. After partition, following a majority of the NWFP voters going for Pakistan in a controversial referendum,[60] Ghaffar Khan resigned himself to their choice and took an oath of allegiance to the new country on February 23, 1948, during a session of the Constituent Assembly, and his second son, Wali Khan, "played by the rules of the political system" as well.[61]

Mahatma Gandhi's view

Mahatma Gandhi was against the division of India on the basis of religion. He once wrote:

I find no parallel in history for a body of converts and their descendants claiming to be a nation apart from the parent stock.[62][63][64][65][66]

Maulana Sayyid Abul Kalam Azad's view

Maulana Sayyid Abul Kalam Azad was a member of the Indian National Congress and was known as a champion of Hindu-Muslim unity.[67] He argued that Muslims were native to India and had made India their home.[67] Cultural treasures of undivided India such as the Red Fort of Delhi to the Taj Mahal of Agra to the Badshahi Mosque of Lahore reflected a Indo-Islamic cultural legacy in the whole country, which would remain inaccessible to Muslims if they were divided through a partition of India.[67] He opposed the partition of India for as long as he lived.[68]

View of the Deobandi ulema

The two-nation theory and the partition of India were vehemently opposed by the vast majority of Deobandi Islamic religious scholars, being represented by the Jamiat Ulema-e-Hind that supported both the All India Azad Muslim Conference and Indian National Congress.[69][56][70][13] The principal of Darul Uloom Deoband, Maulana Hussain Ahmad Madni, not only opposed the two-nation theory but sought to redefine the Indian Muslim nationhood. He advocated composite Indian nationalism, believing that nations in modern times were formed on the basis of land, culture, and history.[71] He and other leading Deobandi ulama endorsed territorial nationalism, stating that Islam permitted it.[55] Despite opposition from most Deobandi scholars, Ashraf Ali Thanvi and Mufti Muhammad Shafi instead tried to justify the two-nation theory and concept of Pakistan.[72][73]

Post-partition debate

Since the partition, the theory has been subjected to animated debates and different interpretations on several grounds. Mr. Niaz Murtaza, a Pakistani scholar with a doctoral degree from the Berkeley-based University of California, wrote in his Dawn column (April 11, 2017):

If the two-nation theory is eternally true, why did Muslims come to Hindu India from Arabia? Why did they live with and rule Hindus for centuries instead of giving them a separate state based on such a theory? Why did the two-nation theory emerge when Hindu rule became certain? All this can only be justified by an absurd sense of superiority claiming a divine birthright to rule others, which many Muslims do hold despite their dismal morals and progress today.

Many common Muslims criticized the two-nation theory as favoring only the elite class of Muslims, causing the deaths of over one million innocent million people.[12]

In his memoirs entitled Pathway to Pakistan (1961), Chaudhry Khaliquzzaman, a prominent leader of the Pakistan movement and the first president of the Pakistan Muslim League, has written: "The two-nation theory, which we had used in the fight for Pakistan, had created not only bad blood against the Muslims of the minority provinces but also an ideological wedge, between them and the Hindus of India.".[74] He further wrote: "He (Huseyn Shaheed Suhrawardy) doubted the utility of the two-nation theory, which to my mind also had never paid any dividends to us, but after the partition, it proved positively injurious to the Muslims of India, and on a long-view basis for Muslims everywhere."[75]

According to Khaliquzzaman, on August 1, 1947, Jinnah invited the Muslim League members of India's constituent assembly to a farewell meeting at his Delhi house.

Mr. Rizwanullah put some awkward questions concerning the position of Muslims, who would be left over in India, their status and their future. I had never before found Mr. Jinnah so disconcerted as on that occasion, probably because he was realizing then quite vividly what was immediately in store for the Muslims. Finding the situation awkward, I asked my friends and colleagues to end the discussion. I believe as a result of our farewell meeting, Mr. Jinnah took the earliest opportunity to bid goodbye to his two-nation theory in his speech on 11 August 1947 as the governor general-designate and President of the constituent assembly of Pakistan.[76]

To Indian nationalists, the British intentionally divided India in order to keep the nation weak.[77]

In his August 11, 1947 speech, Jinnah had spoken of composite Pakistani nationalism, effectively negating the faith-based nationalism that he had advocated in his speech of March 22, 1940. In his August 11 speech, he said that non-Muslims would be equal citizens of Pakistan and that there would be no discrimination against them. "You may belong to any religion or caste or creed that has nothing to do with the business of the state." On the other hand, far from being an ideological point (transition from faith-based to composite nationalism), it was mainly tactical: Dilip Hiro says that "extracts of this speech were widely disseminated" in order to abort the communal violence in Punjab and the NWFP, where Muslims and Sikhs-Hindus were butchering each other and which greatly disturbed Jinnah on a personal level, but "the tactic had little, if any, impact on the horrendous barbarity that was being perpetrated on the plains of Punjab."[78] Another Indian scholar, Venkat Dhulipala, who in his book Creating a New Medina precisely shows that Pakistan was meant to be a new Medina, an Islamic state, and not only a state for Muslims, so it was meant to be ideological from the beginning with no space for composite nationalism, in an interview also says that the speech "was made primarily keeping in mind the tremendous violence that was going on", that it was "directed at protecting Muslims from even greater violence in areas where they were vulnerable", "it was pragmatism", and to vindicate this, the historian goes on to say that "after all, a few months later, when asked to open the doors of the Muslim League to all Pakistanis irrespective of their religion or creed, the same Jinnah refused, saying that Pakistan was not ready for it."[79]

The theory has faced scepticism because Muslims did not entirely separate from Hindus and about one-third of all Muslims continued to live in post-partition India as Indian citizens alongside a much larger Hindu majority.[80][81] The subsequent partition of Pakistan itself into the present-day nations of Pakistan and Bangladesh was cited as proof both that Muslims did not constitute one nation and that religion alone was not a defining factor for nationhood.[80][81][82][83][84]

Impact of Bangladesh's creation

Some historians have claimed that the theory was a creation of a few Muslim intellectuals.[85] Altaf Hussain, founder of the Muttahida Qaumi Movement believes that history has proved the two-nation theory wrong.[86] He contended, "The idea of Pakistan was dead at its inception when the majority of Muslims (in Muslim-minority areas of India) chose to stay back after partition, a truism reiterated in the creation of Bangladesh in 1971".[87] The Canadian scholar Tarek Fatah termed the two-nation theory "absurd".[88]

In his Dawn column Irfan Husain, a well-known political commentator, observed that it has now become an "impossible and exceedingly boring task of defending a defunct theory".[89] However some Pakistanis, including a retired Pakistani brigadier, Shaukat Qadir, believe that the theory could only be disproved with the reunification of independent Bangladesh, and Republic of India.[90]

According to Prof. Sharif al Mujahid, one of the most preeminent experts on Jinnah and the Pakistan movement, the two-nation theory was relevant only in the pre-1947 subcontinental context.[91] He is of the opinion that the creation of Pakistan rendered it obsolete because the two nations had transformed themselves into Indian and Pakistani nations.[92] Muqtada Mansoor, a columnist for Express newspaper, has quoted Farooq Sattar, a prominent leader of the MQM, as saying that his party did not accept the two-nation theory. "Even if there was such a theory, it has sunk in the Bay of Bengal."[93]

In 1973, there was a movement against the recognition of Bangladesh in Pakistan. Its main argument was that Bangladesh's recognition would negate the two-nation theory. However, Salman Sayyid says that 1971 is not so much the failure of the two-nation theory and the advent of a united Islamic polity despite ethnic and cultural difference, but more so the defeat of "a Westphalian-style nation-state, which insists that linguistic, cultural and ethnic homogeneity is necessary for high 'sociopolitical cohesion'. The break-up of united Pakistan should be seen as another failure of this Westphalian-inspired Kemalist model of nation-building, rather than an illustration of the inability of Muslim political identity to sustain a unified state structure."[94]

Some Bangladesh academics have rejected the notion that 1971 erased the legitimacy of the two-nation theory as well, like Akhand Akhtar Hossain, who thus notes that, after independence, "Bengali ethnicity soon lost influence as a marker of identity for the country's majority population, their Muslim identity regaining prominence and differentiating them from the Hindus of West Bengal",[95] or Taj ul-Islam Hashmi, who says that Islam came back to Bangladeshi politics in August 1975, as the death of Sheikh Mujibur Rahman "brought Islam-oriented state ideology by shunning secularism and socialism." He has quoted Basant Chatterjee, an Indian Bengali journalist, as rebuking the idea of the failure of two-nation theory, arguing that, had it happened, Muslim-majority Bangladesh would have joined Hindu-majority West Bengal in India.[96]

J. N. Dixit, a former ambassador of India to Pakistan, thought the same, stating that Bangladeshis "wanted to emerge not only as an independent Bengali country but as an independent Bengali Muslim country. In this, they proved the British Viceroy Lord George Curzon (1899-1905) correct. His partition of Bengal in 1905 creating two provinces, one with a Muslim majority and the other with a Hindu majority, seems to have been confirmed by Bangladesh's emergence as a Muslim state. So one should not be carried away by the claim of the two-nation theory having been disproved."[97] Dixit has narrated an anecdote. During Prime Minister Zulfikar Ali Bhutto's visit to Dhaka in July 1974, after Sheikh Mujibur Rahman went to Lahore to attend the Islamic summit in February 1974: "As the motorcade moved out, Mujib's car was decorated with garlands of chappals and anti-Awami League slogans were shouted together with slogans such as: "Bhutto Zindabad", and "Bangladesh-Pakistan Friendship Zindabad"." He opines that Bhutto's aim was "to revive the Islamic consciousness in Bangladesh" and "India might have created Bangladesh, but he would see that India would have to deal with not one, but two Pakistans, one in the west and another in the east."[98]

Ethnic and provincial groups in Pakistan

Several ethnic and provincial leaders in Pakistan also began to use the term "nation" to describe their provinces and argued that their very existence was threatened by the concept of amalgamation into a Pakistani nation on the basis that Muslims were one nation.[99][100] It has also been alleged that the idea that Islam is the basis of nationhood embroils Pakistan too deeply in the affairs of other predominantly Muslim states and regions, prevents the emergence of a unique sense of Pakistani nationhood that is independent of reference to India, and encourages the growth of a fundamentalist culture in the country.[101][102][103]

Also, because partition divided Indian Muslims into three groups (of roughly 190 million people each in India, Pakistan and Bangladesh) instead of forming a single community inside a united India that would have numbered about 470 million people and potentially exercised great influence over the entire subcontinent. So, the two-nation theory is sometimes alleged to have ultimately weakened the position of Muslims on the subcontinent and resulted in large-scale territorial shrinkage or skewing for cultural aspects that became associated with Muslims (e.g., the decline of Urdu language in India).[104][105]

This criticism has received a mixed response in Pakistan. A poll conducted by Gallup Pakistan in 2011 shows that an overwhelming majority of Pakistanis held the view that separation from India was justified in 1947.[106] Pakistani commentators have contended that two nations did not necessarily imply two states, and the fact that Bangladesh did not merge into India after separating from Pakistan supports the two-nation theory.[107][90]

Others have stated that the theory is still valid despite the still-extant Muslim minority in India, and asserted variously that Indian Muslims have been "Hinduized" (i.e., lost much of their Muslim identity due to assimilation into Hindu culture), or that they are treated as an excluded or alien group by an allegedly Hindu-dominated India.[108] Factors such as lower literacy and education levels among Indian Muslims as compared to Indian Hindus, longstanding cultural differences, and outbreaks of religious violence such as those occurring during the 2002 Gujarat riots in India are cited.[3]

Pan-Islamic identity

The emergence of a sense of identity that is pan-Islamic rather than Pakistani has been defended as consistent with the founding ideology of Pakistan and the concept that "Islam itself is a nationality," despite the commonly held notion of "nationality, to Muslims, is like idol worship."[109][110] While some have emphasized that promoting the primacy of a pan-Islamic identity (over all other identities) is essential to maintaining a distinctiveness from India and preventing national "collapse", others have argued that the two-nation theory has served its purpose in "midwifing" Pakistan into existence and should now be discarded to allow Pakistan to emerge as a normal nation-state.[102][111]

Post-partition perspectives in India

The state of India officially rejected the two-nation theory and chose to be a secular state, enshrining the concepts of religious pluralism and composite nationalism in its constitution.[20][13]

Nevertheless, in post-independence India, the two-nation theory helped advance the cause of Hindu nationalist groups seeking to identify a "Hindu national culture" as the core identity of an Indian. This allows the acknowledgment of the common ethnicity of Hindus and Muslims while requiring that all adopt a Hindu identity to be truly Indian. From the Hindu nationalist perspective, this concedes the ethnic reality that Indian Muslims are "flesh of our flesh and blood of our blood" but still presses for an officially recognized equation of national and religious identity, i.e., that "an Indian is a Hindu."[112]

The theory and the very existence of Pakistan has caused Indian far-right extremist groups to allege that Indian Muslims "cannot be loyal citizens of India" or any other non-Muslim nation, and are "always capable and ready to perform traitorous acts".[113][114] Constitutionally, India rejects the two-nation theory and regards Indian Muslims as equal citizens.[115] The official Indian perspective maintains that the partition of India was a result of Britain's divide-and-rule policy that aimed at dividing Hindus and Muslims after they united together to fight the British in the Indian Rebellion of 1857.[23]

See also

References

- Challenges and Opportunities in Global Approaches to Education. IGI Global. 2019. p. 58. ISBN 978-1-5225-9777-3.

Indian Partition of 1947 was a significant communal segregation in the world's history following a huge mass migration. Based on Jinnah's “Two-Nation Theory”, a utopian state named Pakistan came into being. Islam as a religion was the only connector between the two long-distanced (by more than 2200 kilometers) parts of Pakistan: East and West (Rafique, 2015). However, the East Pakistanis (present day Bangladeshis) soon found themselves in a vulnerable position in concern of political and economic power. Corrupt West Pakistani leaders persecuted the peoples in the East side.

- Liaquat Ali Khan (1940), Pakistan: The Heart of Asia, Thacker & Co. Ltd., ISBN 9781443726672

- Mallah, Samina (2007). "Two-Nation Theory Exists". Pakistan Times. Archived from the original on 11 November 2007.

- O'Brien, Conor Cruise (August 1988), "Holy War Against India", The Atlantic Monthly Quoting Jinnah: "Islam and Hinduism are not religions in the strict sense of the word, but in fact different and distinct social orders, and it is only a dream that the Hindus and Muslims can ever evolve a common nationality.... To yoke together two such nations under a single state ... must lead to a growing discontent and final destruction of any fabric that may be so built up for the government of such a state."

- Shakir, Moin (18 August 1979), "Always in the Mainstream (Review of Freedom Movement and Indian Muslims by Santimay Ray)", Economic and Political Weekly, 14 (33): 1424, JSTOR 4367847

- M. M. Sankhdher; K. K. Wadhwa (1991), National unity and religious minorities, Gitanjali Publishing House, ISBN 978-81-85060-36-1

- Vinayak Damodar Savarkar; Sudhakar Raje (1989), Savarkar commemoration volume, Savarkar Darshan Pratishthan

- N. Chakravarty (1990), "Mainstream", Mainstream, 28 (32–52)

- Carlo Caldarola (1982), Religions and societies, Asia and the Middle East, Walter de Gruyter, pp. 262–263, ISBN 978-90-279-3259-4,

They simply advocated a democratic state in which all citizens, Muslims and non-Muslims alike, would enjoy equal rights.

- S. Harman (1977), Plight of Muslims in India, DL Publications, ISBN 978-0-9502818-2-7

- M. M. Sankhdher (1992), Secularism in India, dilemmas and challenges, Deep & Deep Publication, ISBN 9788171004096

- Rabasa, Angel; Waxman, Matthew; Larson, Eric V.; Marcum, Cheryl Y. (2004). The Muslim World After 9/11. Rand Corporation. ISBN 978-0-8330-3755-8.

However, many Indian Muslims regarded India as their permanent home and supported the concept of a secular, unified state that would include both Hindus and Muslims. After centuries of joint history and coexistence, these Muslims firmly believed that India was fundamentally a multireligious entity and that Muslims were an integral part of the state. Furthermore, cleaving India into independent Muslim and Hindu states would be geographically inconvenient for millions of Muslims. Those living in the middle and southern regions of India could not conveniently move to the new Muslim state because it required to travel over long distances and considerable financial resources. In particular, many lower-class Muslims opposed partition because they felt that a Muslim state would benefit only upper-class Muslims. At independence, the division of India into the Muslim state of Pakistan and the secular state of India caused a massive migration of millions of Muslims into Pakistan and Hindus into India, along with the death of over one million people in the consequent riots and chaos. The millions of Muslims who remained in India by choice or providence became a smaller and more interspersed minority in a secular and democratic state.

- Ali, Asghar Ali (2006). They Too Fought for India's Freedom: The Role of Minorities. Hope India Publications. p. 24. ISBN 978-81-7871-091-4.

Mr. Jinnah and his Muslim League ultimately propounded the two nation theory. But the 'Ulama rejected this theory and found justification in Islam for composite nationalism.

- Rafiq Zakaria (2004), Indian Muslims: where have they gone wrong?, Popular Prakashan, ISBN 978-81-7991-201-0

- Janmahmad (1989), Essays on Baloch national struggle in Pakistan: emergence, dimensions, repercussions, Gosha-e-Adab

- Stephen P. Cohen (2004), The idea of Pakistan, Brookings Institution Press, ISBN 978-0-8157-1502-3

- Sisson, Richard; Rose, Leo E. (1990). War and Secession: Pakistan, India, and the Creation of Bangladesh. University of California Press. p. 10. ISBN 978-0-520-06280-1.

- Ahmad Salim (1991), Pashtun and Baloch history: Punjabi view, Fiction House

- Akbar, Malik Siraj (19 July 2018). "In Balochistan, Dying Hopes for Peace". The New York Times. Retrieved 25 September 2019.

Increasing attacks by the Islamic State in Balochistan are connected to Pakistan’s failed strategy of encouraging and using Islamist militants to crush Baloch rebels and separatists.

- Scott, David (2011). Handbook of India's International Relations. Routledge. p. 61. ISBN 978-1-136-81131-9.

On the other hand the Republic of India rejected the very foundations of the two-nation theory and, refusing to see itself a Hindu India, it proclaimed and rejoiced in religious pluralism supported by a secular state ideology and for a geographical sense of what India was.

- Abbott Lawrence Lowell (1918), Greater European governments, Harvard University Press

- Mukherjee, Nationhood and Statehood in India 2001, p. 6: "Obviously the inhabitants of the subcontinent were considered by the Puranic authors as forming a nation, at least geographically and culturally. There were feelings among at least a section of the public that the whole of the subcontinent (or by and large the major part of it) was inhabited by a people or a group of peoples sharing a link-culture or some common features of an "umbrella" culture in so deep a manner that the could be called by a common name—Bhārati. So geographically and culturally, if not politically and ethnically, the Bhāratis were a nation."

- Tharoor, Shashi (10 August 2017). "The Partition: The British game of 'divide and rule'". Al Jazeera.

- "Information of Pakistan". 23 July 2010. Archived from the original on 23 July 2010. Retrieved 4 April 2019.

- Gilani, Waqar (30 March 2004). "History books contain major distortions". Daily Times. Archived from the original on 6 June 2011.

- Prakash K. Singh (2008). Encyclopaedia on Jinnah. 5. Anmol Publications. p. 331. ISBN 978-8126137794.

- "Independence Through Ages". bepf.punjab.gov.pk. Retrieved 5 April 2019.

- Singh, Prakash K. (2009). Encyclopaedia on Jinnah. Anmol Publications. ISBN 9788126137794.

- Fazal, Tanweer (2014). Nation-state and Minority Rights in India: Comparative Perspectives on Muslim and Sikh Identities. Routledge. p. 162. ISBN 978-1-317-75179-3.

- Arthur Buehler, "Ahmad Sirhindī: Nationalist Hero, Good Sufi, or Bad Sufi?" in Clinton Bennett, Charles M. Ramsey (ed.), South Asian Sufis: Devotion, Deviation, and Destiny, A&C Black (2012), p. 143

- M. Ikram Chaghatai (ed.),Shah Waliullah (1703 - 1762): His Religious and Political Thought, Sang-e-Meel Publications (2005), p. 275

- Akbar Ahmed, Jinnah, Pakistan and Islamic Identity: The search for Saladin, Routledge (2005), p. 121

- Ramachandra Guha, Makers of Modern India, Harvard University Press (2011), p. 65

- Hussain, Akmal (1989), "The Crisis of State Power in Pakistan", in Ponna Wignaraja; Akmal Hussain (eds.), The Challenge in South Asia: Development, Democracy and Regional Cooperation, United Nations University Press, p. 201, ISBN 978-0-8039-9603-8

- Gerald James Larson, India's Agony Over Religion: Confronting Diversity in Teacher Education, SUNY Press (1995), p. 184

- S.M. Ikram, Indian Muslims and Partition of India, Atlantic Publishers & Dist (1995), p. 308

- Wolpert, Stanley A. (12 July 2005), Jinnah of Pakistan, Oxford University Press, pp. 47–48, ISBN 978-0-19-567859-8

- Ranjan, Amit (2018). Partition of India: Postcolonial Legacies. Taylor & Francis. ISBN 978-0-429-75052-6.

- Komireddi, Kapil (17 April 2015). "The long, troubling consequences of India's partition that created Pakistan". The Washington Post. Retrieved 31 May 2020.

The idea of Pakistan emerged from the anxieties and prejudices of a decaying class of India’s Muslim elites, who claimed that Islam’s purity would be contaminated in a pluralistic society.

- Ian Copland, India 1885-1947: The Unmaking of an Empire, Pearson Education (2001), pp. 57-58

- Rubina Saigol (1995), Knowledge and identity: articulation of gender in educational discourse in Pakistan, ASR Publications, ISBN 978-969-8217-30-3

- Mahomed Ali Jinnah (1992) [1st pub. 1940], Problem of India's future constitution, and allied articles, Minerva Book Shop, Anarkali, Lahore, ISBN 978-969-0-10122-8

- Shaukatullah Ansari (1944), Pakistan – The Problem of India, Minerva Book Shop, Anarkali, Lahore, ISBN 9781406743531

- Nasim A. Jawed (1999), Islam's political culture: religion and politics in predivided Pakistan, University of Texas Press, ISBN 978-0-292-74080-8

- Sajid Khakwani (29 May 2010), امہ یا ریاست؟ (Ummah or Statehood?), News Urdu, archived from the original on 12 June 2010, retrieved 9 July 2010

- Ambedkar, Bhimrao Ramji (1945). Pakistan or the Partition of India. Mumbai: Thackers.

- Bhimrao Ramji Ambedkar, Pakistan Or Partition of India, Thacker limited (1945), p. 324

- "Iqbal and the Pakistan Movement". Lahore: Iqbal Academy. Retrieved 22 April 2006.

- Official website, Nazaria-e-Pakistan Foundation. "Excerpt from the presidential address delivered Muhammad Ali Jinnah in Lahore on March 22, 1940". Archived from the original on 28 June 2006. Retrieved 22 April 2006.

- https://sites.google.com/site/cabinetmissionplan/mountbatten-and-jinnah-negotiations-on-pakistan-april-

- "Minority Interest". The Herald. Pakistan Herald Publications. 22 (1–3): 15. 1991.

When the Quaid-e-Azam was fighting his battle for Pakistan, only the Ahmadiya community, out of all religious groups, supported him.

- Khalid, Haroon (6 May 2017). "Pakistan paradox: Ahmadis are anti-national but those who opposed the country's creation are not". Scroll.in.

- Balzani, Marzia (2020). Ahmadiyya Islam and the Muslim Diaspora: Living at the End of Days. Routledge. ISBN 978-1-351-76953-2.

- Valentine, Simon Ross (2008). Islam and the Ahmadiyya Jamaʻat: History, Belief, Practice. Columbia University Press. p. 204. ISBN 978-0-231-70094-8.

In 1948, after the creation of Pakistan, when the Dogra Regime and the Indian forces were invading Kashmir, the Ahmadi community raised a volunteer force, the Furqan Force which actively fought against Indian troops.

- Yoginder Sikand (2005). Bastions of the Believers: Madrasas and Islamic Education in India. Penguin Books India. pp. 228–. ISBN 978-0-14-400020-3.

- Kukreja, Veena; Singh, M. P. (2005). Pakistan: Democracy, Development, and Security Issues. SAGE Publishing. ISBN 978-93-5280-332-3.

The latter two organizations were offshoots of the pre-independence Jamiat-ul-Ulema-i-Hind and were comprised mainly of Deobandi Muslims (Deoband was the site for the Indian Academy of Theology and Islamic Jurisprudence). The Deobandis had supported the Congress Party prior to partition in the effort to terminate British rule in India. Deobandis also were prominent in the Khilafat movement of the 1920s, a movement Jinnah had publicly opposed. The Muslim League, therefore, had difficulty in recruiting ulema in the cause of Pakistan, and Jinnah and other League politicians were largely inclined to leave the religious teachers to their tasks in administering to the spiritual life of Indian Muslims. If the League touched any of the ulema it was the Barelvis, but they too never supported the Muslim League, let alone the latter's call to represent all Indian Muslims.

- Ambedkar, B.R. (1940). Pakistan or the Partition of India.

- Qasmi, Ali Usman; Robb, Megan Eaton (2017). Muslims against the Muslim League: Critiques of the Idea of Pakistan. Cambridge University Press. p. 2. ISBN 9781108621236.

- Qaiser, Rizwan (2005), "Towards United and Federate India: 1940-47", Maulana Abul Kalam Azad a study of his role in Indian Nationalist Movement 1919–47, Jawaharlal Nehru University/Shodhganga, Chapter 5, pp. 193, 198, hdl:10603/31090

- Phadnis, Aditi (2 November 2017). "Britain created Pakistan". Rediff. Retrieved 2 June 2020.

- Christophe Jaffrelot, The Pakistan Paradox: Instability and Resilience, Oxford University Press (2015), p. 153

- Prof. Prasoon (1 January 2010). My Letters.... M.K.Gandhi. Pustak Mahal. p. 120. ISBN 978-81-223-1109-9.

- David Arnold (17 June 2014). Gandhi. Taylor & Francis. p. 170. ISBN 978-1-317-88234-3.

- Mridula Nath Chakraborty (26 March 2014). Being Bengali: At Home and in the World. Routledge. p. 203. ISBN 978-1-317-81890-8.

- Anil Chandra Banerjee (1981). Two Nations: The Philosophy of Muslim Nationalism. Concept Publishing Company. p. 236. GGKEY:HJDP3TYZJLW.

- Bhikhu Parekh (25 November 1991). Gandhi's Political Philosophy: A Critical Examination. Palgrave Macmillan UK. p. 178. ISBN 978-1-349-12242-4.

- Naqvi, Saeed (31 January 2020). "Why didn't we listen to Maulana Azad's warning?". Deccan Chronicle. Retrieved 2 June 2020.

- "Maulana Azad opposed Partition till last breath: Experts". Business Standard. 23 February 2016. Retrieved 2 June 2020.

- Qasmi, Muhammadullah Khalili (2005). Madrasa Education: Its Strength and Weakness. Markazul Ma'arif Education and Research Centre (MMERC). p. 175. ISBN 978-81-7827-113-2.

The Deobandis opposed partition, rejected the two-nation theory and strongly supported the nationalist movement led by the Congress.

- Qasmi, Ali Usman; Robb, Megan Eaton (2017). Muslims against the Muslim League: Critiques of the Idea of Pakistan. Cambridge University Press. p. 2. ISBN 9781108621236.

- Muhammad Moj (1 March 2015). The Deoband Madrassah Movement: Countercultural Trends and Tendencies. Anthem Press. pp. 81–. ISBN 978-1-78308-389-3.

- Shafique Ali Khan (1988). The Lahore resolution: arguments for and against : history and criticism. Royal Book Co. ISBN 9789694070810.

- Ronald Inglehart (2003). Islam, Gender, Culture, and Democracy: Findings from the World Values Survey and the European Values Survey. De Sitter Publications. p. 28. ISBN 978-0-9698707-7-7.

- Khaliquzzaman, Pathway to Pakistan 1961, p. 390.

- Khaliquzzaman, Pathway to Pakistan 1961, p. 400.

- Khaliquzzaman, Pathway to Pakistan 1961, p. 321.

- Yousaf, Nasim (31 August 2018). "Why Allama Mashriqi opposed the partition of India?". Global Village Space. Retrieved 24 January 2019.

- Dilip Hiro, The Longest August: The Unflinching Rivalry Between India and Pakistan, Hachette UK (2015), p. 101

- Ajaz Ashraf (28 June 2016). "The Venkat Dhulipala interview: 'On the Partition issue, Jinnah and Ambedkar were on the same page". Scroll.in. Retrieved 11 April 2019.

- Husain Haqqani (2005), Pakistan: Between Mosque and Military, Carnegie Endowment, ISBN 978-0-87003-214-1

- "کالم نگار جہالت اور جذبات فروشی کا کام کرتے ہیں ('Columnists are peddling ignorance and raw emotionalism')", Urdu Point, retrieved 22 October 2010

- Craig Baxter (1994), Islam, Continuity and Change in the Modern World, Syracuse University Press, ISBN 978-0-8156-2639-8

- Craig Baxter (1998), Bangladesh: From a Nation to a State, Westview Press, p. xiii, ISBN 978-0-8133-3632-9

- Altaf Hussain, Two Nation Theory Archived 31 August 2006 at the Wayback Machine, Muttahida Quami Movement, April 2000.

- Amaury de Riencourt (Winter 1982–83). "India and Pakistan in the Shadow of Afghanistan". Foreign Affairs. Archived from the original on 19 May 2003.

- Altaf Hussain, The slogan of two-nation theory was raised to deceive the one hundred million Muslims of the subcontinent, Muttahida Quaumi Movement, 21 June 2000

- Faruqui, Ahmad (19 March 2005). "Jinnah's unfulfilled vision: The Idea of Pakistan by Stephen Cohen". Asia Times. Pakistan. Retrieved 6 October 2009.

- Aarti Tikoo Singh (19 April 2013). "Tarek Fatah: India is the only country where Muslims exert influence without fear". The Times of India. Retrieved 29 April 2016.

- Irfan Husain, A discourse of the deaf, Dawn, 4 November 2000

- "India and Partition". Daily Times.

- https://jinnah-institute.org/feature/august-11-1947-jinnahs-paradigmatic-shift/Dawn, December 25, 2004

- The News, March 23, 2011

- Daily Express, Lahore, March 24, 2011

- Salman Sayyid, Recalling the Caliphate: Decolonisation and World Order, C. Hurst & Co. (2014), p. 126

- Akhand Akhtar Hossain, "Islamic Resurgence in Bangladesh's Culture and Politics: Origins, Dynamics and Implications" in Journal of Islamic Studies, Volume 23, Issue 2, May 2012, Pages 165–198

- Taj ul-Islam Hashmi, "Islam in Bangladesh politics" in Hussin Mutalib and Taj ul-Islam Hashmi (editors), Islam, Muslims and the Modern State: Case Studies of Muslims in Thirteen Countries, Springer (2016), pp. 100-103

- J. N. Dixit, India-Pakistan in War and Peace, Routledge (2003), p. 387

- J. N. Dixit, India-Pakistan in War and Peace, Routledge (2003), p. 225

- Institute of Policy Studies, Islamabad (2005), Pakistan political perspective, Volume 14

- Sayid Ghulam Mustafa; Ali Ahmed Qureshi (2003), Sayyed: as we knew him, Manchhar Publications

- Paul R. Brass; Achin Vanaik; Asgharali Engineer (2002), Competing nationalisms in South Asia: essays for Asghar Ali Engineer, Orient Blackswan, ISBN 978-81-250-2221-3

- Shahid Javed Burki (1999), Pakistan: fifty years of nationhood, Westview Press, ISBN 978-0-8133-3621-3

- Moonis Ahmar (2001), The CTBT debate in Pakistan, Har-Anand Publications, ISBN 978-81-241-0818-5

- Ghulam Kibria (2009), A shattered dream: understanding Pakistan's underdevelopment, Oxford University Press, ISBN 978-0-19-577947-9

- Gurpreet Mahajan (2002), The multicultural Path: Issues of Diversity and Discrimination in Democracy, Sage, ISBN 978-0-7619-9579-1

- "Majority Pakistanis think separation from India was justified: Gallup poll". Express Tribune. 12 September 2011. Retrieved 28 December 2011.

- Raja Afsar Khan (2005), The concept, Volume 25

- Yvonne Yazbeck Haddad; John L. Esposito (2000), Muslims on the Americanization path?, Oxford University Press US, ISBN 978-0-19-513526-8

- Tarik Jan (1993), Foreign policy debate, the years ahead, Institute of Policy Studies, ISBN 9789694480183

- S. M. Burke (1974), Mainsprings of Indian and Pakistani foreign policies, University of Minnesota Pres, ISBN 978-0-8166-0720-4

- Anwar Hussain Syed (1974), China & Pakistan: diplomacy of an entente cordiale, University of Massachusetts Press, ISBN 978-0-87023-160-5

- Sridharan, Kripa (2000), "Grasping the Nettle: Indian Nationalism and Globalization", in Leo Suryadinata (ed.), Nationalism and globalization: east and west, Institute of Southeast Asian Studies, pp. 294–318, ISBN 978-981-230-078-2

- Yogindar Sikand (2006), Muslims in India: Contemporary Social and Political Discourses, Hope India Publications, 2006, ISBN 9788178711157

- Clarence Maloney (1974), Peoples of South Asia, Holt, Rinehart and Winston, 1974, ISBN 9780030849695

- Jasjit Singh (1999), Kargil 1999: Pakistan's fourth war for Kashmir, Knowledge World, 1999, ISBN 9788186019221

Bibliography

- Mukherjee, Bratindra Nath (2001), Nationhood and Statehood in India: A historical survey, Regency Publications, ISBN 978-81-87498-26-1

- Khaliquzzaman, Choudhry (1961), Pathway to Pakistan, Lahore: Brothers' Publisher (published 1993)

External links

- Story of Pakistan website, Jin Technologies (Pvt) Limited (December 2003). "The Ideology of Pakistan: Two-Nation Theory". Retrieved 22 April 2006.

- A critique of the Two Nation Theory: Sharpening the saw; by Varsha Bhosle; 26 July 1999; Rediff India

Story of the Nation divided by group connected by heart; two nation theory E-GYANKOSH