A. A. K. Niazi

Amir Abdullah Khan Niazi (Urdu: امیر عبداللہ خان نیازی; b. 1915 – 1 February 2004), HJ(Withdrawn), MC, popularly known as A.A.K. Niazi or General Niazi was a lieutenant-general in the Pakistan Army and the last Governor of East Pakistan, known for commanding the Eastern Command of the Pakistan Army in East Pakistan (now Bangladesh) during the Eastern and the Western Fronts of the Indo-Pakistani war until the unilateral surrendering on the 16 December 1971 to Lieutenant General Jagjit Singh Aurora (GOC-in-C) of the Eastern Command and the Bengali Liberation Forces.[1]

Amir Abdullah Khan Niazi | |

|---|---|

Amir Abdullah Khan Niazi (1915–2004) | |

| Governor of East Pakistan | |

| In office 14 December 1971 – 16 December 1971 | |

| President | Yahya Khan |

| Prime Minister | Nurul Amin |

| Preceded by | Abdul Motaleb Malik |

| Succeeded by | Office disestablished |

| Commander of Eastern Command | |

| In office 4 April 1971 – 16 December 1971 | |

| Lieutenant | Brigadier Baqir Siddiqui (Chief of Staff, Eastern Command) |

| Preceded by | Lt. Gen. Tikka Khan |

| Succeeded by | Post disestablished |

| Personal details | |

| Born | Amir Abdullah Khan Niazi 1915 Mianwali, Punjab, British India (Present-day Pakistan) |

| Died | 1 February 2004 (aged 88 or 89) Lahore, Punjab, Pakistan |

| Resting place | Military Graveyard in Lahore |

| Citizenship | |

| Alma mater | Officers Training School, Bangalore Quetta Staff College |

| Signature | |

| Military service | |

| Branch/service | |

| Years of service | 1942–1974 |

| Rank | (Rank stripped/withdrawn) |

| Unit | 4/7 Rajput Regiment |

| Commands | GOC 10th Infantry Division GOC 8th Infantry Division Commander Parachute Training School |

| Battles/wars | World War II

Indo-Pakistani war of 1965 Bangladesh Liberation War |

| Awards | |

Niazi had the area responsibility of defending the borders of East Pakistan from India and was held morally responsible by authors and critics within Pakistan's military for surrendering the Eastern Command, consisting of ~92,000 - 95,000 servicemen (sources vary),[2] to the Indian Army when the preparations were underway to lay siege on Dacca.[3][4]:170 Thus ending the liberation struggle led by the Bengali Mukti Bahini which also ended the war with India amid a unilateral ceasefire called by Pakistan in 1971.[5]

After taken and held as a prisoner of war by the Indian Army, he was repatriated to Pakistan on 30 April 1975. Niazi was dishonored from his military service after confessing at the War Enquiry Commission led by Chief Justice Hamoodur Rahman.[6] The War Commission leveled accusations against him for human rights violations, supervising the smuggling of goods during the Indian supported civil war in the East and held him morally responsible for military failure during the course of the war.[7][8][9] Niazi however rejected the base allegations and sought a military court-martial while insisting that he had acted according to the orders of the Army GHQ. The court-martial was never granted.[8]

After the war, he remained active in national politics and supported the ultra-conservative agenda under the conservative alliance against Prime Minister Zulfiqar Ali Bhutto's government in 1970s.[1]

In 1999, he authored the book Betrayal of East Pakistan, in which he provided his "own true version of the events of that fateful year."[10] On 1 February 2004, Niazi died in Lahore, Punjab, Pakistan.[11]

Biography

Early life and British Indian Army career

Amir Abdullah Niazi was born in 1915 in a small village, Balo Khel, located on the east bank of the Indus River in Mianwali, Punjab, British India.[4]:12[12][13] After matriculating from a local high-school in Mianwali, he joined the British Indian Army as an "Y cadet" in 1941 and was selected for an emergency commission as he had passed out from the Officers Training School in Bangalore.[4]:12

He gained commission during the World War 2 on 8 March 1942 (following a 4 months training) into the 4/7 Rajput Regiment which was then-part of the 161st Infantry Brigade led by the Brigadier D.F.W. Warren.[4]:12[14]

World War II and Burma campaigns

On 11 June 1942, Lt. Niazi was stationed in the Kekrim Hills located in regions of Assam-Manipur to participate in the Burma front.[12] That spring, he was part of the 14th Army of the British Army and the British Indian Army commanded by General Slim.[12]

During this period, the 14th Army had halted the offense against the Japanese Imperial Army at the Battle of Imphal and elsewhere in bitterly fought battles along the Burma front.[12] His valor of actions were commendable and General Slim described his gallantry in a lengthy report to General Headquarters, India, about his judgment of the best course of action.[12] They agreed on Niazi's skill in completely surprising the enemy, his leadership, coolness under fire, and his ability to change tactics, create diversions, extricate his wounded and withdraw his men.[12] At the Burmese front in 1944, Lt. Niazi impressed his superior officers when he commanded a platoon that initiated an offense against the Japanese Imperial Army at the Bauthi-Daung tunnels.[12]

Lt. Niazi's gallantry had impressed his British commanders in the GHQ India and they wanted to award him the Distinguished Service Order, but his rank was not high enough for such a decoration.[12] During the campaign, Brigadier D.F.W. Warren, commanding officer of the 161st Infantry Division of the British Army, gave Niazi the soubriquet "Tiger" for his part in a ferocious fight with the Japanese.[12] After the conflict, the British Government decorated Lt. Niazi with the Military Cross for leadership, judgement, quick thinking and calmness under pressure in action along the border with Burma.[12] On 11 July 1944, his military commission was confirmed as permanent and the new service number was issued as ICO-906.[4]:12

On 15 December 1944, Lord Wavell, Viceroy of India, flew to Imphal and knighted General Slim and his corps commanders Stopford, Scoones, and Christison in the presence of Lord Mountbatten.[15][16] Only two British Indian Army officers were chosen to be decorated at that ceremony— one was Lt. Niazi and the other was Major Sam Manekshaw of the Frontier Force Regiment.[17]

After World War II, in 1945, he was promoted as captain and sent to attend the Command and Staff College in Quetta which he graduated with a staff course degree under then-Lt. Col. Yahya Khan.[4]:12

Staff and war appointments in Pakistan Army

In 1947 the United Kingdom, through the Indian Independence Act 1947, announced their intention of partitioning British India amid the failure of the 1946 Cabinet Mission to India. After the creation of Pakistan in August 1947, Major Niazi decided to opt for Pakistani citizenship and joined the newly established Pakistan Army where his S/No was redesigned as PA–477 by the Ministry of Defence of Pakistan.[4]:12 He continued serving at the Command and Staff College in Quetta and briefly completed his tenure as an instructor.[18]

His career in the army progressed well and he continued to climb in army grade. In the 1950s as he was decorated with the Sitara-i-Khidmat (lit. Service Star) for his contributions and service with the army.[19] In 1960–64, he was promoted as Brigadier and offered discussion on infiltration tactics at the Command and Staff College.[14] Subsequently, he published an article on infiltration and promoted talks on military-supported local rebellion against the enemy.[14]

Brigadier Niazi went on to participate in the Indo-Pakistani War of 1965, the second war with India, as he commanded the paratrooper brigade stationed in Sialkot.[20] Initially, he commanded the 5th AK Brigade directing military operations in Jammu and Kashmir but later assumed the command of 14th (Para) Brigade in Zafarwal sector where he gained public notability when he participated in the famous Battle of Chawinda tank battle against the Indian Army which halted the Indians troop rotation.[21] His role in a tank battle led him to be decorated with the Hilal-e-Jurat by the President of Pakistan.[21]

His leadership credentials led him to be appointed martial law administrator of both Karachi and Lahore to maintain control of law in the cities of West Pakistan in 1966–67.[22] In 1968, he was promoted as Major-General and made General Officer Commanding (GOC) of the 8th Infantry Division, stationed in Sialkot, Punjab, Pakistan.[23] In 1969, Major-General Niazi was made GOC of 10th Infantry Division, stationed in Lahore, Punjab, Pakistan. In 1971, he was promoted to three star assignment and promoted as Lieutenant-General, initially appointed Commander of the IV Corps in Lahore.

East Pakistan

Eastern Command in 1971 war

Lieutenant-General Niazi volunteered for transfer to East Pakistan when Lieutenant-General Bahadur Sher Khan declined the post.[1] There were two other generals who had also refused postings in the East. However, Niazi said "yes" without necessarily realizing the risks involved and how to counter them.[1]

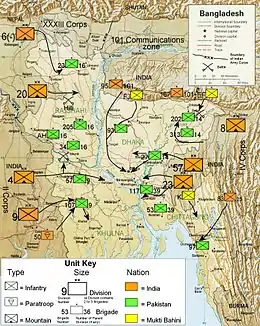

After General Tikka Khan had initiated the Operation Searchlight military crackdown in March 1971, many officers had declined to be stationed in the East and Niazi arrived in Dhaka on 4 April 1971 to assume the Eastern Command from Tikka Khan.[24] Furthermore, the mass killing of Bengali intellectuals in 1971 at the University of Dhaka had made the East Pakistani people hostile towards the Pakistani military, which made it hard for Niazi to overcome the situation.[25] On 10/11 April 1971, he headed a meeting of his senior commanders to assess the situation but, according to eyewitnesses, he used abusive language aimed at the Bengali rebels.[24] From May through August 1971, the Indian Army trained Mukti Bahini led Operation Jackpot, a series of counter guerrilla campaigns against the Eastern Command, and Niazi began taking countermeasures against the Bengali rebellion.[26] By June 1971, he sent reports on the rebellion and noted that 30,000 insurgents were hurriedly trained by India at the India-East Pakistan border.[26] In August 1971, Niazi formulated a plan to defend the borders from the advancing Indian Army based on a "fortress concept" which mean converting the border towns and villages into a stronghold.[27]

By September 1971, he was appointed the martial law administrator in order to provide his support to Governor Abdul Motaleb Malik who appointed a civilian cabinet.[28] On the issue of the 1971 East Pakistan genocide, Niazi had reportedly told his public relations officer and press secretary, Major Siddique Salik, that "we will have to account every single rape and killing when back in (West) Pakistan. God never spares the Tyrant."[29][30]

The Government of East Pakistan appointed Niazi as commander of the Eastern Command, and Major-General Rao Farman Ali as their military adviser for the East Pakistan Rifles and East Pakistan Coast Guard.[28] In October 1971, he created and deployed two ad hoc divisions to strengthen the defence of the East from further infiltration.[27]

In October 1971, Niazi lost contact with the Pakistan Army GHQ and was virtually independent in controlling the Eastern Command from the central government in Islamabad.[31] In November 1971, General Abdul Hamid Khan, the Chief of Staff, warned him of an imminent Indian attack on the East and advised him to redeploy the Eastern Command on a tactical and political base ground but this was not implemented due to shortage of time.[32]:303–304 In a public message, Niazi was praised by Abdul Hamid Khan saying:"The whole nation is proud of you and you have their full support".[33]

No further orders or clarification was issued in regards to the orders as Niazi had been caught unawares when the Indian Army planned to launch a full assault on East Pakistan.[32]:303 On 3 December 1971, the Pakistan Air Force (PAF) launched Operation Chengiz Khan, the pre-emptive PAF air-strikes on Indian Air Force bases that officially led to start of the Indo-Pakistani War of 1971, the third war with India.[32]:304 According to author Sagar, Niazi, surprisingly, was not aware of the attack and had no prior knowledge of the attack.[32]:304

Credibility of this claim is given by Niazi's press secretary and public relations officer, then-Major Siddique Salik, who wrote in Witness to Surrender, that Niazi's chief of staff Brigadier Baqir Siddiqi reportedly scolded him of not notifying Niazi and his staff of an aerial attack on India.[34]

Surrendering of Eastern Command

When Indian Army soldiers crossed the borders and charged towards Dhaka, General Niazi panicked when he came to realise the real nature of the Indian strategy and became frantically nervous when the Indian Army successfully penetrated the defence of the East.[32]:304 Niazi's military staff further regretted not heeding the intelligence warnings issued 20 years earlier in the 1952 'Cable 1971' report compiled by Major K. M. Arif, the military intelligence official on Niazi's staff.[35]

According to the testimonies provided by Major-General Farman Ali in the War Enquiry Commission, Niazi's morale collapsed as early as 7 December and he cried frantically over the progress report presented to Governor Abdul Motaleb.[36]:183 He ultimately blamed Lieutenant-General Tikka Khan for turning the East Pakistanis hostile towards the Government of Pakistan, and the creation of the Mukti Bahini.[37] Major accusations were also directed toward Lieutenant-General Yakob Ali Khan, Admiral S. M. Ahsan and Major-General Ali for aggravating the crisis, but Niazi had to bear most responsibility for all that happened in the East.[38]:627

General Niazi, alongside with his deputy Rear-Admiral Mohammad Shariff, nervously tried reassessing the situation to halt the Indian Army's penetration by directing joint army-navy operations with no success.[39][40] The Pakistani military combat units found themselves involved in a guerrilla war with the Mukti Bahini under Atul Osmani, and were unprepared and untrained for such warfare.[41]

On 9 December, the Indian Government accepted the sovereignty of Bangladesh and extended its diplomatic mission to the Provisional Government of Bangladesh.[42] This eventually led Governor Abdul Motaleb to resign from his post and he took refuge with his entire cabinet at the Red Cross shelter at the Inter-Continental Dacca on 14 December.[19]

Niazi eventually took control of the civilian government and reportedly received a telegram on 16 December 1971 from President Yahya Khan: "You have fought a heroic battle against overwhelming odds. The nation is proud of you ... You have now reached a stage where further resistance is no longer humanly possible nor will it serve any useful purpose ... You should now take all necessary measures to stop the fighting and preserve the lives of armed forces personnel, all those from West Pakistan and all loyal elements".[4]:73–74

During this time, the Special Branch of the East Pakistan Police notified Niazi of the joint Indo-Bengali siege of Dhaka as the Eastern Command led by Lieutenant-General Jagjit Singh Aurora began encircling Dhaka.[43] Niazi then appealed for a conditional ceasefire to Lieutenant-General Jagjit Singh Aurora which called for transferring power to the elected government, but without the surrender of the Eastern Command led by Niazi.[43] This offer was rejected by Indian Army's Chief of Army Staff General Sam Manekshaw and he set a deadline for surrender, President Yahya Khan considered it as "illegitimate.[17] [43] Niazi then once again appealed for a cease-fire, but Manekshaw set a deadline for surrender, failing which Dhaka would come under siege.[17]

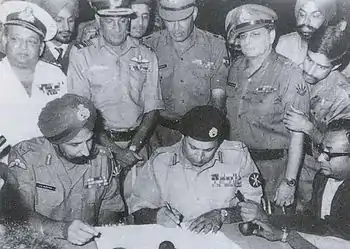

Subsequently, the Indian Army began encircling Dhaka and Lieutenant-General Jagjit Singh Aurora sent a message through Major-General Rafael Jacob that issued an ultimatum to surrender in a "30-minutes" time window on 16 December 1971.[44] Niazi agreed to surrender and sent a message to Manekshaw despite many army officers declined to obey, although they were legally bound.[45] The Indian Army commanders, Lieutenant General Sagat Singh, Lieutenant General J.S. Aurora, and Major-General Rafael Farj Jacob arrived at Dhaka via helicopter with the surrender documents.[44]

The surrender took place at Ramna Race Course, in Dhaka at local time 16:31 on 16 December 1971. Niazi signed the Instrument of Surrender and handed over his personal weapon to J. S. Aurora in the presence of Indian and Bangladesh force commanders. With Niazi, nearly 90,000 personnel of the Eastern Command surrendered to the joint Indian and Bangladesh Army.[46]

War prisoner, repatriation, and politics

Niazi, who was repatriated to Pakistan, was handed over to Lieutenant-General Abdul Hamid, then corps commander of the IV Corps, by Indian Army from the Wagha checkpoint in Lahore District, Punjab, in April 1975, in a symbolic gesture of last war prisoner held by India.[6]:620 Upon arriving in Lahore, he immediately refrained from speaking to news media correspondents, and was immediately taken under the custody of the Pakistan Army's Military Police (MP) who shifted him via helicopter to Lahore Cantonment where he was detained despite his strong protests.[4]:170 He was immediately dismissed from his military commission and his war honors were withdrawn from him.[47]

Subsequently, he was placed in solitary confinement for sometime, though he was later released.[48] Being the last to return supported his reputation as a "soldier's general", but did not shield him from the scorn he faced in Pakistan, where he was blamed for the surrender. Bhutto discharged Niazi after stripping him of his military rank, the pension usually accorded to retired soldiers, and his military decorations.[46] His three-star rank was eventually reduced to Major-General, a two-star rank, but he was dismissed from the service in July 1975.:144[28]

He was also denied his military pension and medical benefits, though he lodged a strong complaint against the revoking of his pension.[49] In 1980s, the Ministry of Defence quietly changed the status of "dismissal" to "retirement" but did not restore his rank.[50] The change of order allowed Niazi to seek a pension and the medical assistance benefits enjoyed by retired military personnel.[50]

Niazi remained active in national politics in 1970s and supported the ultraconservative agenda on a conservative Pakistan National Alliance platform against the Pakistan Peoples Party.[1] In 1977, he was again detained by the police when the Operation Fair Play military coup occurred on 5 July, overthrowing the government of Prime Minister Zulfikar Ali Bhutto. Martial law was enforced and Niazi sought retirement from politics.[51]

War Enquiry Commission

In 1982, Niazi was summoned and confessed to the War Enquiry Commission led by Chief Justice Hamoodur Rahman and the Supreme Court of Pakistan on the events involving the secession of East Pakistan in April 1975.[52] The War Commission leveled accusations against him of several kinds of ethical misconduct during his tenure in East Pakistan. The Commission opined that Niazi supervised the betel leaf and imported paan using an official aircraft, from East Pakistan to Pakistan.[53][54]

The Commission indicted him for corruption and moral turpitude while noting his bullying of junior officers who opposed his orders.[55] Niazi tried placing the blame on the Yahya administration, his military adviser Maj. Gen. Farman Ali, Admiral S.M. Ahsan, Lieutenant-General Yakob Ali, and the military establishment. The Commission partially accepted his claims by critically noting that General Niazi was a Supreme Commander of the Eastern Command, and that he was responsible for everything that happened in the East."[38]:452 Though he showed no regrets, Niazi refused to accept responsibility for the Breakup of East Pakistan and squarely blamed President Yahya.[56] The Commission endorsed his claims that Yahya was to blame, but noted that Niazi was the Commander who lost the East.[56]

The Commission recommended a court-martial be held by the Judge Advocate General that would indite Niazi for serious breaches of military discipline and the military code.[36]:185 No such court-martial took place,[57] but nonetheless, he was politically maligned and indited with the war crimes that took place in East Pakistan. Niazi did not accepted the Commission's inquiries and fact-findings, believing that the Commission had no understanding of military matters.[58] Niazi claimed that a court-martial would have besmirched the names of those who later rose to great heights, and that he was being used as a scapegoat.[58]

In 1998, he authored a book, The Betrayal of East Pakistan, which was a record of the events that led to 16 December 1971.[1] In 2001, he appeared on Views On News, and was interviewed by Dr. Shahid Masood at ARY News shortly before his death.[59]

Death and legacy

After giving an interview to ARY News, Niazi died on 1 February 2004 in Lahore, Punjab, Pakistan. He was buried in a Military Graveyard in Lahore.[1]

Political commentators described Niazi's legacy as a mixture of the foolhardy, and the ruthless.[54] He was also noted for making audacious statements like: "Dacca will fall only over my dead body".[60] According to Pakistani author, Akbar S. Ahmed, he had even hatched a far-fetched plan to "cross into India and march up the Ganges and capture Delhi and thus link up with Pakistan."[61]

This he called the "Niazi corridor theory" explaining: "It was a corridor that the Quaid-e-Azam demanded and I will obtain it by force of arms".[62] In a plan he presented to the central government in June 1971, he stated in his own words that "I would capture Agartala and a big chunk of Assam, and develop multiple thrusts into Indian Bengal. We would cripple the economy of Calcutta by blowing up bridges and sinking boats and ships in Hooghly River and create panic amongst the civilians. One air raid on Calcutta would set a sea of humanity in motion to get out of Calcutta".[62][63]

A journalist from the Dawn newspaper had observed him thus: When I last met him on 30 September 1971, at his force headquarters in Kurmitola, he was full of beans.[1]

From the mass of evidence coming before the War Enquiry Commission from witnesses, both civil and military, there is little doubt that Niazi came to acquire a bad reputation in sex matters, and this reputation has been consistent during his postings in Sialkot, Lahore and East Pakistan.[64] The allegations regarding his indulgence in the export of Pan by using or abusing his position in the Eastern Command and as Commander of his command also prima facie appear to be well-founded.[65]

References

- Siddiqi, PA, Brigadier A. R. (13 February 2004). "Gen A. A. K. (Tiger) Niazi: an appraisal". Dawn. Islamabad. Retrieved 8 January 2017.

- "A leaf from history: The fall and surrender". Dawn (newspaper). 13 May 2012.

- Joura, J. S. (2011). A Blessed Life. New Delhi: Sanbun Publishers. pp. 109–110. ISBN 9788170103851.

- Bhattacharya, Brigadier Samir (2014). NOTHING BUT!. India: Partridge Publishing. ISBN 9781482817201. Retrieved 8 January 2017.

- Tucker, Spencer C., ed. (2010). "The Cold War and the Nuclear Age, 1945–2008". A Global Chronology of Conflict: From the Ancient World to the Modern Middle East [6 volumes]: From the Ancient World to the Modern Middle East. Denver, CO: ABC-CLIO. p. 2475. ISBN 978-1-85109-672-5.

- News Review on South Asia and Indian Ocean. Institute for Defence Studies & Analyses. 1983. p. 620.

- "Gendercide Watch". Gendercide.org. Retrieved 10 November 2011.

- Mir, Hamid (16 December 2014). "Forty-three years of denial". The Indian Express (Opinion). Noida, India. Retrieved 8 January 2017.

- Ahmed, Khalid (7 July 2012). "'Genetic engineering' in East Pakistan". The Express Tribune. Islamabad, Pakistan. Retrieved 8 January 2017.

- Khan., Niazi, Amir Abdullah (1999). The betrayal of East Pakistan. Karachi, Sindh, Pakistan: Oxford University Press, Karachi University. ISBN 978-0195792751.

- Jaffor Ullah, A H (6 February 2004). "On General Niazi's departure". The Daily Star. Dhaka. Retrieved 8 January 2017.

- "Lieutenant-General A. A. K. Niazi". Times. London. 11 March 2004. Archived from the original on 14 May 2009. Retrieved 9 July 2011.

- "General A A K Niazi". www.mianwalionline.com. Retrieved 8 January 2017.

- Fair, C. Christine (2014). Fighting to the End: The Pakistan Army's Way of War. Oxford University Press. pp. 230–231. ISBN 978-0-19-989270-9.

- "Investiture on the Imphal plain: Viceroy Wavell Knights Slim, Christison, Scoones and Stopford". Imperial War Museum. Retrieved 6 October 2018.

- "No. 36720". The London Gazette (Supplement). 26 September 1944. p. 4473.

- Bose, Sarmila (15 November 2010). "Sarmila Bose on events of 1971". The Times of Bombay. Retrieved 9 July 2011.

- Sehgal, Ikram ul-Majeed (2002). "Unknown". Defence Journal. 6: 24. Cite uses generic title (help)

- BD Government, BD Government. "BANGABHABAN – The President House of Bangladesh". bangabhaban.gov.bd. BD Government. Archived from the original on 7 December 2016. Retrieved 8 January 2017.

- Singh, Lt Gen Harbakhsh. War Despatches: Indo–Pak Conflict 1965. Lancer Publishers LLC. p. 2. ISBN 978-1-935501-59-6.

- "Asia Week: A.A.K. Niazi- The Man who Lost East Pakistan". Asiaweek. 1982. pp. 6–7.

- "The Rediff Interview with Lt Gen A A Khan Niazi". Rediff. 2 February 2004.

- Wahab, A. T. M. Abdul (2015) [First published 2004]. Mukti Bahini wins victory: Pak military oligarchy divides Pakistan in 1971 (3rd ed.). Pan Pacific Venture. p. 96. ISBN 9789847130446.

Lieutenant General Amir Abdullah Khan Niazi who assumed the command of Eastern Command on April 11, 1971 whom I met as my GOC 8 Division in Sialkot in 1968.

- Cardozo, Ian (2016). In Quest of Freedom: The War of 1971 – Personal Accounts by Soldiers from India and Bangladesh. Bloomsbury Publishing. p. xxx. ISBN 9789386141668.

- De, Sibopada (2005). Illegal migrations and the North-East : a study of migrants from Bangladesh. New Delhi: Published for Maulana Abul Kalam Azad Institute of Asian Studies by Anamika Publishers & Distributors. pp. 35–40. ISBN 978-8179750902.

- Gates, Scott; Roy, Kaushik (2016). Unconventional Warfare in South Asia: Shadow Warriors and Counterinsurgency. Routledge. p. xxxi. ISBN 978-1-317-00540-7.

- Barua, Pradeep (5 April 2013). The Military Effectiveness of Post-Colonial States. BRILL. p. 108. ISBN 978-90-04-24911-0.

- Rizvi, H. (15 May 2000). Military, State and Society in Pakistan. Springer. pp. 138–139. ISBN 978-0-230-59904-8.

- Sālik, PA, Brigadier Ṣiddīq (1979). Witness To Surrender. Oxford University Press. p. 167. ISBN 9788170621089.

- Sinh, Ramdhir (18 October 2013). A Talent for War: The Military Biography of Lt Gen Sagat Singh. Vij Books India Pvt Ltd. p. content. ISBN 9789382573739.

- Jackson, Robert (17 June 1978). South Asian Crisis: India — Pakistan — Bangla Desh. Springer. p. 108. ISBN 978-1-349-04163-3.

- Sagar, Krishna Chandra (1997). The War of the Twins. Northern Book Centre. ISBN 9788172110826.

- Sisson, Richard; Rose, Leo E. (1990). War and Secession: Pakistan, India, and the Creation of Bangladesh. University of California Press. p. 229. ISBN 978-0-520-07665-5.

- Salik, Saddique (1986). "Judgement Day". In Jaffrey, Major Syed Zamir; Azim, Fazl (eds.). Witness of Surrender: Urdu Version (in Urdu) (2nd ed.). Karachi: Urdu Publishing Co. pp. 139–140.

- Salik, Saddique (1979). "Preface". In Jaffry, Major Syed Zamir; Azim, Fazl (eds.). Witness of Surrender: Urdu Version (in Urdu). Rawalpindi: Urdu Books Publishing co. pp. 194–200.

- Jones, Owen Bennett (2002). Pakistan: Eye of the Storm. Yale University Press. p. 183. ISBN 978-0-300-10147-8.

- Gerlach, Christian (14 October 2010). Extremely Violent Societies: Mass Violence in the Twentieth-Century World. Cambridge University Press. p. 142. ISBN 978-1-139-49351-2.

- Nabi, Dr Nuran (27 August 2010). Bullets of '71: A Freedom Fighter's Story. AuthorHouse. ISBN 9781452043838. Retrieved 9 January 2017.

- Malik, Major-General Tajammul Hussain. "The Surrender". Major-General Tajammul Hussain Malik, GOC of 203 Mountain Division. Retrieved 21 December 2011.

- "History: A SOVIET INTELLIGENCE OPERATIVE ON BANGLADESH WAR". History. Soviet History. 16 March 2012. Archived from the original on 5 January 2017. Retrieved 5 January 2017.

- Raja, Dewan Mohammad Tasawwar (2010). O General My General (Life and Works of General M A G Osmany). The Osmany Memorial Trust. pp. 35–109. ISBN 978-984-8866-18-4.

- Preston, Ian (2001). A Political Chronology of Central, South and East Asia. Psychology Press. p. 16. ISBN 978-1-85743-114-8.

- Kapur, Paul (2016). Jihad as Grand Strategy: Islamist Militancy, National Security, and the Pakistani State. Oxford University Press. p. 64. ISBN 978-0-19-061182-8.

- Sengupta, Ramananda. "1971 War: 'I will give you 30 minutes'". Sify. Sify, Sengupta. Retrieved 24 December 2016.

- "Fall of Dhaka 1971". Story Of Pakistan. Story Of Pakistan. 4 June 2002. Retrieved 8 January 2017.

- Orton, Anna (2010). India's Borderland Disputes: China, Pakistan, Bangladesh, and Nepal. Epitome Books. p. 117. ISBN 978-93-80297-15-6.

- Sehgal, Ikram ul-Majeed (2002). "Unknown". Defence Journal: 49. Retrieved 9 January 2017. Cite uses generic title (help)

- Kortenaar, Neil Ten (2005). Self, Nation, Text in Salman Rushdie's "Midnight's Children". McGill-Queen's Press – MQUP. p. 285. ISBN 978-0-7735-2621-1.

- Sehgal, Ikram ul-Majeed (2004). "Unknown". Defence Journal: 49. Cite uses generic title (help)

- News Review on South Asia and Indian Ocean. Institute for Defence Studies & Analyses. 1980s. p. 620.

- Kak, B. L. (1979). Z. A. Bhutto: Notes from the Death Cell. Rādhā Krishna Press. Retrieved 9 January 2017.

- D'Costa, Bina (2011). Nationbuilding, Gender and Crimes in South Asia. Routledge. p. 79. ISBN 978-0-415-56566-0.

- Abbas, Hassan (26 March 2015). Pakistan's Drift into Extremism: Allah, the Army, and America's War on Terror: Allah, the Army, and America's War on Terror. Routledge. p. xcx. ISBN 978-1-317-46327-6.

- Sattar, Babar (23 December 2013). "Bigoted and smug". Dawn. Retrieved 9 January 2017.

- Singh, Maj Gen (retd) Randhir (1999). A Talent for War: The Military Biography of Lt Gen Gandu Singh. New Delhi: Vij Books India Pvt Ltd. p. contents. ISBN 9789382652236.

- Cloughley, Brian (5 January 2016). A History of the Army: Wars and Insurrections. Skyhorse Publishing, Inc. p. contents. ISBN 978-1-63144-039-7.

- Tripathi, Salil (2016). The Colonel Who Would Not Repent: The Bangladesh War and Its Unquiet Legacy. Yale University Press. p. 179. ISBN 978-0-300-22102-2.

- Faruqui, Ahmad (2003). Rethinking the National Security: The Price of Strategic Hyopia. Ashgate. pp. 68–70. ISBN 978-0-7546-1497-5.

- "TV SHOWS". Dr. Shahid Masood. Retrieved 9 January 2017.

- https://web.archive.org/web/20061207140306/http://www.bharat-rakshak.com/1971/Dec12/index.html

- Rosser, Yvette. "Abuse of History in Pakistan: Bangladesh to Kargil". Pakistan Facts. Archived from the original on 17 March 2006.

- The Betrayal of East Pakistan. A.A.K Niazi

- Online snippets of Niazi's comments

- Mookherjee, Nayanika (23 October 2015). The Spectral Wound: Sexual Violence, Public Memories, and the Bangladesh War of 1971. Duke University Press. pp. contents pages. ISBN 978-0-8223-7522-7.

- "Commission Report". Archived from the original on 4 December 2007. Retrieved 9 March 2007.

External links

- Pakistan: Independence and Military Succession

- Video of Surrender By General Niazi, A. A. K.

- Lt. Gen A.A.K. Niazi

| Military offices | ||

|---|---|---|

| Preceded by Lieutenant General Tikka Khan |

Commander of Eastern Command 7 April 1971 – 16 December 1971 |

Succeeded by Office abolished |

| Political offices | ||

| Preceded by Abdul Motaleb Malik |

Governor of East Pakistan 14 December 1971 – 16 December 1971 |

Succeeded by Office abolished |