Aeacus

Aeacus (/ˈiːəkəs/; also spelled Eacus; Ancient Greek: Αἰακός Aiakos or Aiacos) was a mythological king of the island of Aegina in the Saronic Gulf.

Family

Aeacus was the son of Zeus by Aegina, a daughter of the river-god Asopus, and thus, brother of Damocrateia.[1] In some accounts, his mother was Europa and thus possible brother to Minos, Rhadamanthus and Sarpedon.[2][3] He was the father of Peleus, Telamon and Phocus and was the grandfather of the Trojan war warriors Achilles and Telemonian Ajax. In some accounts, Aeacus had a daughter called Alcimache who bore Medon to Oileus of Locris.[4] Aeacus’ sons Peleus and Telamon were jealous of Phocus and killed him. When Aeacus learned about the murder, he exiled Peleus and Telamon.[5]

Mythology

Birth and early days

Aeacus was born on the island of Oenone or Oenopia, where Aegina had been carried by Zeus to secure her from the anger of her parents; afterward, this island became known as Aegina.[6][7][8][9][10] Some traditions related that, at the time when Aeacus was born, Aegina was not yet inhabited, and that Zeus either changed the ants (μύρμηκες) of the island into the men (Myrmidons) over whom Aeacus ruled, or he made the men grow up out of the earth.[6][11][12] Ovid, on the other hand, supposed that the island was not uninhabited at the time of the birth of Aeacus, instead stating that during the reign of Aeacus, Hera, jealous of Aegina, ravaged the island bearing the name of the latter by sending a plague or a fearful dragon into it, by which nearly all its inhabitants were carried off. Afterward, Zeus restored the population by changing the ants into men.[13][14][15]

| Greek underworld |

|---|

| Residents |

| Geography |

| Famous Tartarus inmates |

| Visitors |

These legends seem to be a mythical account of the colonization of Aegina, which seems to have been originally inhabited by Pelasgians, and afterwards received colonists from Phthiotis, the seat of the Myrmidons, and from Phlius on the Asopus. While he reigned in Aegina, Aeacus was renowned in all Greece for his justice and piety, and was frequently called upon to settle disputes not only among men, but even among the gods themselves.[16][17] He was such a favourite with the latter, that when Greece was visited by a drought as a consequence of a murder that had been committed, the oracle of Delphi declared that the calamity would not cease unless Aeacus prayed to the gods to end it.[6][18] Aeacus prayed, and as a result, the drought ceased. Aeacus then demonstrated his gratitude by erecting a temple to Zeus Panhellenius on Mount Panhellenion,[19] and afterward, the Aeginetans built a sanctuary on their island called Aeaceum, which was a square temple enclosed by walls of white marble. Aeacus was believed in later times to be buried under the altar of this sacred enclosure.[20]

Later adventures

A legend preserved in Pindar relates that Apollo and Poseidon took Aeacus as their assistant in building the walls of Troy.[21] When the work was completed, three dragons rushed against the wall, and though the two that attacked the sections of the wall built by the gods fell down dead, the third forced its way into the city through the portion of the wall built by Aeacus. Thereafter, Apollo prophesied that Troy would fall at the hands of Aeacus's descendants, the Aeacidae (i.e. his sons Telamon and Peleus joined Heracles when he sieged the city during Laomedon's rule. Later, his great grandson Neoptolemus was present in the wooden horse).

Aeacus was also believed by the Aeginetans to have surrounded their island with high cliffs in order to protect it against pirates.[22] Several other incidents connected to the story of Aeacus are mentioned by Ovid.[23] By Endeïs Aeacus had two sons, Telamon (father of Ajax and Teucer) and Peleus (father of Achilles), and by Psamathe a son, Phocus, whom he preferred to the former two sons, both of whom conspired to kill Phocus during a contest, and then subsequently fled from their native island.

In the afterlife

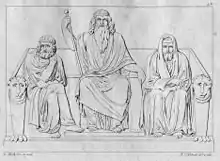

After his death, Aeacus became one of the three judges in Hades (along with the Cretan brothers Rhadamanthus and Minos)[24][25] and, according to Plato, was specifically concerned with the shades of Europeans upon their arrival to the underworld.[26][27] In works of art he was depicted bearing a sceptre and the keys of Hades.[6][28] Aeacus had sanctuaries in both Athens and in Aegina,[20][29][30] and the Aeginetans regarded him as the tutelary deity of their island by celebrating the Aeacea in his honor.[31]

In The Frogs (405 BC) by Aristophanes, Dionysus descends to Hades and proclaims himself to be Heracles. Aeacus, lamenting the fact that Heracles had stolen Cerberus, sentences Dionysus to Acheron to be tormented by the hounds of Cocytus, the Echidna, the Tartesian eel, and Tithrasian Gorgons.

Alexander the Great traced his ancestry through his mother to Aeacus.

See also

| Wikisource has the text of the 1911 Encyclopædia Britannica article Aeacus. |

- Chinvat Bridge, the bridge of the dead in Persian cosmology

- Sraosha, Mithra and Rashnu, guardians and judges of souls in Zoroastrian tradition

References

- Scholia on Pindar, Olympian Ode 9, 107

- Schmitz, Leonhard (1867), "Aeacus", in Smith, William (ed.), Dictionary of Greek and Roman Biography and Mythology, 1, Boston, pp. 22–23

- Compare Plato, Gorgias, 524a

- Scholia on Iliad, 13. 694

- Roman, L., & Roman, M. (2010). Encyclopedia of Greek and Roman mythology., p. 12, at Google Books

- Bibliotheca iii. 12. § 6

- Gaius Julius Hyginus, Fabulae 52

- Pausanias ii. 29. § 2

- comp. Nonn. Dionys. vi. 212

- Ovid, Metamorphoses vi. 113, vii. 472, &c.

- Hesiod, Fragm. 67, ed. Gottling

- Pausanias, l.c.

- Ovid, Metamorphoses vii. 520

- comp. Hygin. Fab. 52

- Strabo, viii. p. 375

- Pindar, Isthmian Odes viii. 48, &c.

- Pausanias, i. 39. § 5

- Diodorus Siculus, iv. 60, 61

- Pausanias, ii. 30. § 4

- Pausanias, ii. 29. § 6

- Pindar, Olympian Odes viii. 39, &c.

- Pausanias, ii. 29. § 5

- Ovid, Metamorphoses vii. 506, &c., ix. 435, &c

- Ovid, Metamorphoses xiii. 25

- Horace, Carmen ii. 13. 22

- Plato. Gorgias, p.524a

- Isocrates, Evagoras 15

- Pindar, Isthmian Odes viii. 47, &c.

- Hesychius s.v.

- Schol. ad Pind. Nem. xiii. 155

- Pindar, Nemean Odes viii. 22

Sources

This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Smith, William, ed. (1870). "Aeacus". Dictionary of Greek and Roman Biography and Mythology.

This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Smith, William, ed. (1870). "Aeacus". Dictionary of Greek and Roman Biography and Mythology.