Eos

In Greek mythology, Eos (/ˈiːɒs/; Ionic and Homeric Greek Ἠώς Ēṓs, Attic Ἕως Héōs, "dawn", pronounced [ɛːɔ̌ːs] or [héɔːs]; Aeolic Αὔως Aúōs, Doric Ἀώς Āṓs)[3] is a Titaness and the goddess[4] of the dawn, who rose each morning from her home at the edge of the Oceanus.

| Eos | |

|---|---|

Personification of the Dawn | |

_-_Dawn_(1881).jpg.webp) L’Aurore by William-Adolphe Bouguereau (1881) | |

| Abode | Sky |

| Symbol | Saffron, Cloak, Roses, Tiara, Cicada, Horse |

| Personal information | |

| Parents | Hyperion and Theia |

| Siblings | Helios and Selene |

| Consort | Astraeus |

| Children | Anemoi and Astraea |

| Equivalents | |

| Roman equivalent | Aurora |

| Hinduism equivalent | Ushas[1] |

| Japanese equivalent | Ame-no-Uzume[2] |

Like Roman Aurora and Rigvedic Ushas, Ēṓs continues the name of an earlier Indo-European dawn goddess, Hausos.

Etymology

The Proto-Greek form of Ἠώς / Ēṓs has been reconstructed as *ἀυhώς / auhṓs, and in Mycenaean Greek as *hāwōs.[3][5] According to Robert S. P. Beekes, the loss of the initial aspiration could be due to metathesis.[3] It is cognate to the Vedic goddess Ushas, Lithuanian goddess Aušrinė, and Roman goddess Aurora (Old Latin Ausosa), all three of whom are also goddesses of the dawn.[1]

All four are considered derivatives of the Proto-Indo-European stem *h₂ewsṓs (later *Ausṓs), "dawn". The root also gave rise to Proto-Germanic *Austrō, Old High German *Ōstara and Old English Ēostre / Ēastre. These cognates led to the reconstruction of a Proto-Indo-European dawn goddess, Hausos (*H₂éwsōs).[1][3]

Family

Eos was the daughter of the Titans Hyperion and Theia: Hyperion, a bringer of light, the One Above, Who Travels High Above the Earth and Theia, The Divine,[6] also called Euryphaessa, "wide-shining"[7] and Aethra, "bright sky".[8] Eos was the sister of Helios, god of the sun, and Selene, goddess of the moon, "who shine upon all that are on earth and upon the deathless gods who live in the wide heaven".[9] The generation of Titans preceded all the familiar deities of Olympus who largely supplanted them. In some accounts, Eos' father was called Pallas.[10][11]

Eos married the Titan Astraeus ("of the Stars") and became the mother of the Anemoi ("winds") namely Zephyrus, Boreas, Notus and Eurus;[8][12] of the Morning Star, Eosphoros (Venus);[13] the Astra ("stars")[14] and of the virgin goddess of justice, Astrae ("starry one").[15][16] Her other notable offspring were Memnon[17][18][19][20][21] and Emathion[22][23] by the Trojan prince, Tithonus. Sometimes, Hesperus,[24] Phaethon[25][26] and Tithonus[27] (different from the lover) were called the children of Eos by the Athenian prince, Cephalus.

Mythology

Goddess of the dawn

The dawn goddess Eos was almost always described with rosy fingers or rosy forearms as she opened the gates of heaven for the Sun to rise.[28] In Homer,[29] her saffron-colored robe is embroidered or woven with flowers;[30] rosy-fingered and with golden arms, she is pictured on Attic vases as a beautiful woman, crowned with a tiara or diadem and with the large white-feathered wings of a bird.

Homer

From The Iliad:

- "Now when Dawn in robe of saffron was hastening from the streams of Oceanus, to bring light to mortals and immortals, Thetis reached the ships with the armor that the god had given her." [31]

- "But soon as early Dawn appeared, the rosy-fingered, then gathered the folk about the pyre of glorious Hector."[32]

She is most often associated with her Homeric epithet "rosy-fingered" Eos Rhododactylos (Ancient Greek: Ἠὼς Ῥοδοδάκτυλος), but Homer also calls her Eos Erigeneia:

Hesiod

- "And after these Erigeneia ["Early-born"] bore the star Eosphoros ("Dawn-bringer"), and the gleaming stars with which heaven is crowned."[34]

Thus Eos, preceded by the Morning Star, is seen as the genetrix of all the stars and planets; her tears are considered to have created the morning dew, personified as Ersa or Herse.[35]

Role in the Gigantomachy

Eos played a small role in the battle of the giants against the gods; when the earth goddess Gaia learned of a prophecy that the giants would perish at the hand of a mortal, Gaia sought to find a herb that would protect them; thus Zeus ordered Eos, as well as her siblings Selene (Moon) and Helios (Sun) not to shine, and harvested all of the plant for himself, denying Gaia the chance to make the giants indestructible.[36]

Orion

Eos is presented as a goddess who fell in love several times. According to Pseudo-Apollodorus, it was the jealous Aphrodite who cursed her to be perpetually in love and have an insatiable sexual desire because once had Eos lain with Aphrodite's sweetheart Ares, the god of war.[37] This caused her to abduct a number of handsome young men.

In the Odyssey, Calypso complains to Hermes about the male gods taking many mortal women as lovers, but not allowing goddesses to do the same. She brings up as example Eos’s love for the hunter Orion, who was killed by Artemis in Ortygia.[38] Apollodorus also mentions Eos’ love for Orion, and adds that she brought him to Delos, where he met Artemis. [39]

Tithonus

Eos fell in love with and abducted Tithonus, a handsome prince from Troy. She went with a request to Zeus, asking him to make Tithonus immortal for her sake. Zeus agreed and granted her wish, but Eos forgot to ask for eternal youth as well for her beloved. For a while, they two lived happily, until Tithonus’ hair started turning grey, and Eos ceased to visit him in bed. But he kept aging, and was soon unable to even move. In the end, Eos locked him up in a chamber, where he withered away, forever a helpless old man.[41] Out of pity, she turned him into a cicada.

Cephalus

The abduction of Cephalus had special appeal for an Athenian audience because Cephalus was a local boy,[42] and so this myth element appeared frequently in Attic vase-paintings and was exported with them. In the literary myths, Eos snatched Cephalus against his will when he was hunting and took him to Syria.[43][44][45][46][47] Although Cephalus was already married to Procris, Eos bore him three sons, including Phaethon and Hesperus, but he then began pining for Procris, causing a disgruntled Eos to return him to Procris, but not before sowing the seeds of doubt in his mind, telling him that it was highly unlikely that Procris had stayed faithful to him this entire time. Cephalus, troubled by her words, asked Eos to change his form into that of a stranger, in order to secretly test Procris’s love for him. Cephalus, disguised, propositioned Procris, who at first declined but eventually gave in. He was hurt by her betrayal, and she left him in shame, but eventually they got back together. This time however it was Procris’s turn to doubt her husband’s fidelity; while hunting, he would often call upon the breeze ('Aura' in Latin, sounding similar to Eos’s Roman equivalent Aurora) to refresh the body. Upon hearing that, Procris followed and spied on him. Cephalus, mistaking her for some wild animal, threw his spear at her, killing his wife.[48] The second-century CE traveller Pausanias knew of the story of Cephalus’s abduction too, though he calls Eos by the name of Hemera, goddess of day.[49]

Trojan War

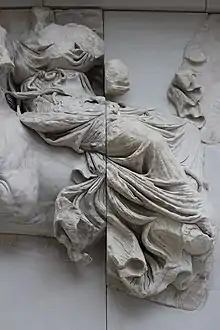

According to Hesiod, by her lover Tithonus, Eos had two sons, Memnon and Emathion.[43] Memnon fought among the Trojans in the Trojan War and fought against Achilles. Pausanias mentions images of Thetis, the mother of Achilles, and Eos begging Zeus on behalf of their sons.[50] In the end, it was Achilles who triumphed and slew Memnon in battle. Mourning greatly over the death of her son, Eos made the light of her brother, Helios the god of the sun, to fade, and begged Nyx, the goddess of the night, to come out earlier, so she could be able to freely steal her son's body undetected by the armies.[51] After his death, Eos asked Zeus to make her son immortal, and he granted her wish.[52] Her image with the dead Memnon across her knees, like Thetis with the dead Achilles are icons that inspired the Christian Pietà.

Divine horses

Eos' team of horses pull her chariot across the sky and are named in the Odyssey as "Firebright" and "Daybright". Quintus described her exulting in her heart over the radiant horses (Lampus and Phaëton) that drew her chariot, amidst the bright-haired Horae, the feminine Hours, climbing the arc of heaven and scattering sparks of fire.[53]

Cult and temples

There are no known temples, shrines, or altars to Eos. However, Ovid seems to allude to the existence of at least two shrines of Eos, as he describes them in plural, albeit few, in the lines:

- [Eos addresses Zeus :] ‘Least I may be of all the goddesses the golden heavens hold – in all the world my shrines are rarest.’[54]

Ovid may therefore have known of at least two such shrines.

Interpretations

Etruscan

Among the Etruscans, the generative dawn-goddess was Thesan. Depictions of the dawn-goddess with a young lover became popular in Etruria in the fifth century, probably inspired by imported Greek vase-painting.[55] Though Etruscans preferred to show the goddess as a nurturer (Kourotrophos) rather than an abductor of young men, the late Archaic sculptural acroterion from Etruscan Cære, now in Berlin, showing the goddess in archaic running pose adapted from the Greeks, and bearing a boy in her arms, has commonly been identified as Eos and Cephalus.[56] On an Etruscan mirror Thesan is shown carrying off a young man, whose name is inscribed as Tinthu.[57]

Roman

The Roman equivalent of Eos is Aurora, also a cognate showing the characteristic Latin rhotacism. Dawn became associated in Roman cult with Matuta, later known as Mater Matuta. She was also associated with the sea harbors and ports, and had a temple on the Forum Boarium. On June 11, the Matralia was celebrated at that temple in honor of Mater Matuta; this festival was only for women during their first marriage.

See also

Notes

- Mallory, J.P.; Adams, D.Q. (2006). The Oxford Introduction to Proto-Indo-European and the Proto-Indo-European World. Oxford, England: Oxford University Press. p. 432. ISBN 978-0-19-929668-2.

- Witzel, Michael (2005). Vala and Iwato: The Myth of the Hidden Sun in India, Japan, and beyond (PDF).

- R. S. P. Beekes, Etymological Dictionary of Greek, Brill, 2009, p. 492.

- Lycophron calls her by an archaic name, Tito (the Titaness). Kerenyi observes that Tito shares a linguistic origin with Eos's lover Tithonus, which belonged to an older, pre-Greek language. (Kerenyi 1951:199 note 637)

- West, Martin L. (2007-05-24). Indo-European Poetry and Myth. OUP Oxford. ISBN 9780199280759.

- Pseudo-Apollodorus, Bibliotheca 1.2.2

- Homeric Hymn to Helios, 1

- Hyginus, Fabulae Preface

- Hesiod, Theogony 371-374

- Ovid, Fasti 4.373 ff

- Valerius Flaccus, Argonautica 2.72 ff

- Nonnus, Dionysiaca 6.18; 37.70 & 47.340

- Cicero wrote: Stella Veneris, quae Φωσφόρος Graece, Latine dicitur Lucifer, cum antegreditur solem, cum subsequitur autem Hesperos; The star of Venus, called Φωσφόρος in Greek and Lucifer in Latin when it precedes, Hesperos when it follows the sun – De Natura Deorum 2, 20, 53.

Pliny the Elder: Sidus appellatum Veneris … ante matutinum exoriens Luciferi nomen accipit … contra ab occasu refulgens nuncupatur Vesper (The star called Venus … when it rises in the morning is given the name Lucifer … but when it shines at sunset it is called Vesper) Natural History 2, 36 - Pseudo-Apollodorus, Bibliotheca 1.2.4

- Aratus, Phaenomena 97–128

- Hyginus, Astronomica 2.25

- Quintus Smyrnaeus, Posthomerica 2.549

- Pindar, Nemean Odes 6.50 ff

- Diodorus Siculus, Bibliotheca historica 4.75.4

- Callistratus, Statuaram Descriptiones 9

- Ovid, Fasti 4.713

- Hesiod, Theogony 984

- Pseudo-Apollodorus, Bibliotheca 3.12.4

- Hyginus, Astronomica 2.42.4

- Pausanias, Graeciae Descriptio 1.3.1

- Hesiod, Theogony 986

- Pseudo-Apollodorus, Bibliotheca 3.181

- Nonnus: "Eos had just shaken off the wing of carefree sleep (Hypnos) and opened the gates of sunrise, leaving the lightbringing couch of Kephalos." (Dionysiaca 27. 1f, in A.L. Rouse's translation).

- Homer, Iliad viii.1 & xxiv.695

- Odyssey vi:48 etc

- Homer, Iliad xix.1

- Homer, Iliad xxiv.776

- Homer, Odyssey xiii.93

- Hesiod, Theogony 378-382

- Ovid, Metamorphoses 13.621-2

- Apollodorus, Library 1. 6. 2

- Pseudo-Apollodorus, Bibliotheca 1.4.4

- Homer, ‘‘Odyssey’’ 5. 120.

- Pseudo-Apollodorus, Bibliotheca 1. 4. 4

- Homer, Odyssey 15.249 ff

- Homeric Hymn to Aphrodite, 318 ff

- Mary R. Lefkowitz, "'Predatory' Goddesses" Hesperia 71.4 (October 2002, pp. 325-344) p. 326.

- Hesiod, Theogony 984ff

- Pseudo-Apollodorus, Bibliotheca 3.14.3

- Pausanias, Graeciae Descriptio 1.3.1

- Hyginus, Fabulae 189

- Ovid, Metamorphoses vii.703 ff

- Ovid, ‘‘Metamorphoses’’ 7. 700-722

- Pausanias remarking on the subjects shown in the Royal Stoa, Athens (i.3.1) and on the throne of Apollo at Amyklai (iii.18.10ff).

- Pausanias, Description of Greece 5. 22. 2

- Philostratus of Lemnos, Imagines 1. 7

- Arctinus of Miletus, Aethiopis summary

- Quintus Smyrnaeus, Posthomerica i.48

- Ovid, Metamorphoses 13.576 ff (translated by Melville)

- Marilyn Y. Goldberg, "The 'Eos and Kephalos' from Cære: Its Subject and Date" American Journal of Archæology 91.4 (October 1987, pp. 605-614) p 607.

- Goldberg 1987:605-614 casts doubt on the boy's identification, in the context of Etruscan and Greek abduction motifs.

- Noted by Goldberg 1987: in I. Mayer-Prokop, Die gravierten etruskischen Griffspiegel archaischen Stils (Heidelberg) 1966, fig. 61.

References

- Aratus Solensis, Phaenomena translated by G. R. Mair. Loeb Classical Library Volume 129. London: William Heinemann, 1921. Online version at the Topos Text Project.

- Aratus Solensis, Phaenomena. G. R. Mair. London: William Heinemann; New York: G.P. Putnam's Sons. 1921. Greek text available at the Perseus Digital Library.

- Diodorus Siculus, The Library of History translated by Charles Henry Oldfather. Twelve volumes. Loeb Classical Library. Cambridge, Massachusetts: Harvard University Press; London: William Heinemann, Ltd. 1989. Vol. 3. Books 4.59–8. Online version at Bill Thayer's Web Site

- Diodorus Siculus, Bibliotheca Historica. Vol 1-2. Immanel Bekker. Ludwig Dindorf. Friedrich Vogel. in aedibus B. G. Teubneri. Leipzig. 1888-1890. Greek text available at the Perseus Digital Library.

- Grimal, Pierre, The Dictionary of Classical Mythology, Wiley-Blackwell, 1996, ISBN 978-0-631-20102-1. "Eos" p. 146

- Gaius Julius Hyginus, Astronomica from The Myths of Hyginus translated and edited by Mary Grant. University of Kansas Publications in Humanistic Studies. Online version at the Topos Text Project.

- Gaius Julius Hyginus, Fabulae from The Myths of Hyginus translated and edited by Mary Grant. University of Kansas Publications in Humanistic Studies. Online version at the Topos Text Project.

- Gaius Valerius Flaccus, Argonautica translated by Mozley, J H. Loeb Classical Library Volume 286. Cambridge, MA, Harvard University Press; London, William Heinemann Ltd. 1928. Online version at theio.com.

- Gaius Valerius Flaccus, Argonauticon. Otto Kramer. Leipzig. Teubner. 1913. Latin text available at the Perseus Digital Library.

- Hesiod, Theogony from The Homeric Hymns and Homerica with an English Translation by Hugh G. Evelyn-White, Cambridge, MA., Harvard University Press; London, William Heinemann Ltd. 1914. Online version at the Perseus Digital Library. Greek text available from the same website.

- Homer, The Iliad with an English Translation by A.T. Murray, Ph.D. in two volumes. Cambridge, MA., Harvard University Press; London, William Heinemann, Ltd. 1924. Online version at the Perseus Digital Library.

- Homer, Homeri Opera in five volumes. Oxford, Oxford University Press. 1920. Greek text available at the Perseus Digital Library.

- Homer, The Odyssey with an English Translation by A.T. Murray, PH.D. in two volumes. Cambridge, MA., Harvard University Press; London, William Heinemann, Ltd. 1919. Online version at the Perseus Digital Library. Greek text available from the same website.

- Kerenyi, Karl. The Gods of the Greeks. Thames and Hudson, 1951.

- Nonnus of Panopolis, Dionysiaca translated by William Henry Denham Rouse (1863-1950), from the Loeb Classical Library, Cambridge, MA, Harvard University Press, 1940. Online version at the Topos Text Project.

- Nonnus of Panopolis, Dionysiaca. 3 Vols. W.H.D. Rouse. Cambridge, MA., Harvard University Press; London, William Heinemann, Ltd. 1940-1942. Greek text available at the Perseus Digital Library.

- Pausanias, Description of Greece with an English Translation by W.H.S. Jones, Litt.D., and H.A. Ormerod, M.A., in 4 Volumes. Cambridge, MA, Harvard University Press; London, William Heinemann Ltd. 1918. Online version at the Perseus Digital Library

- Pausanias, Graeciae Descriptio. 3 vols. Leipzig, Teubner. 1903. Greek text available at the Perseus Digital Library.

- Pindar, Odes translated by Diane Arnson Svarlien. 1990. Online version at the Perseus Digital Library.

- Pindar, The Odes of Pindar including the Principal Fragments with an Introduction and an English Translation by Sir John Sandys, Litt.D., FBA. Cambridge, MA., Harvard University Press; London, William Heinemann Ltd. 1937. Greek text available at the Perseus Digital Library.

- Pseudo-Apollodorus, The Library with an English Translation by Sir James George Frazer, F.B.A., F.R.S. in 2 Volumes, Cambridge, MA, Harvard University Press; London, William Heinemann Ltd. 1921. Online version at the Perseus Digital Library. Greek text available from the same website.

- Publius Ovidius Naso, Fasti translated by James G. Frazer. Online version at the Topos Text Project.

- Publius Ovidius Naso, Fasti. Sir James George Frazer. London; Cambridge, MA. William Heinemann Ltd.; Harvard University Press. 1933. Latin text available at the Perseus Digital Library.

- Publius Ovidius Naso, Metamorphoses translated by Brookes More (1859-1942). Boston, Cornhill Publishing Co. 1922. Online version at the Perseus Digital Library.

- Publius Ovidius Naso, Metamorphoses. Hugo Magnus. Gotha (Germany). Friedr. Andr. Perthes. 1892. Latin text available at the Perseus Digital Library.

- Quintus Smyrnaeus, The Fall of Troy translated by Way. A. S. Loeb Classical Library Volume 19. London: William Heinemann, 1913. Online version at theio.com

- Quintus Smyrnaeus, The Fall of Troy. Arthur S. Way. London: William Heinemann; New York: G.P. Putnam's Sons. 1913. Greek text available at the Perseus Digital Library.

- Smith, William; Dictionary of Greek and Roman Biography and Mythology, London (1873). "Eos"

- The Homeric Hymns and Homerica with an English Translation by Hugh G. Evelyn-White. Homeric Hymns. Cambridge, MA., Harvard University Press; London, William Heinemann Ltd. 1914. Online version at the Perseus Digital Library. Greek text available from the same website.

Further reading

- Jackson, Peter. "Πότνια Αὔως: The Greek Dawn-Goddess and Her Antecedent." Glotta 81 (2005): 116-23. Accessed May 10, 2020. www.jstor.org/stable/40267187.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Eos. |