Aepyornis

Aepyornis is a genus of aepyornithid, one of three genera of ratite birds endemic to Madagascar until their extinction sometime around AD 1000. The species A. maximus weighed up to 540 kilograms (1,200 lb), and until recently was regarded as the largest known bird of all time. However, in 2018 the largest aepyornithid specimens, weighing up to 730 kilograms (1,600 lb), were moved to the related genus Vorombe.[2]

| Aepyornis | |

|---|---|

| |

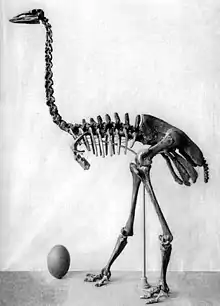

| Aepyornis maximus skeleton and egg | |

Extinct (1000 AD) | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Aves |

| Order: | †Aepyornithiformes |

| Family: | †Aepyornithidae |

| Genus: | †Aepyornis I. Geoffroy Saint-Hilaire, 1851[1] |

| Type species | |

| Aepyornis maximus | |

| Species | |

| |

| |

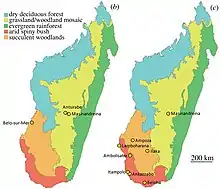

| Map of Madagascar showing where A. hildebrandti (b) and A. maximus (c) specimens have been found | |

Taxonomy

Brodkorb (1963) listed four species of Aepyornis as valid: A. hildebrandti, A. gracilis, A. medius and A. maximus,[3] However, Hume and Walters (2012) listed only one species, A. maximus.[4] Most recently, Hansford and Turvey (2018) recognized only A. hildebrandti and A. maximus.[2]

- ?A. grandidieri Rowley 1867 nomen dubium

- Aepyornis hildebrandti Burckhardt, 1893 (Hildebrandt's elephant-bird)

- Aepyornis gracilis Monnier, 1913

- Aepyornis lentus Milne-Edwards & Grandidier, 1894

- ?Aepyornis minimus

- ?Aepyornis mulleri Milne-Edwards & Grandidier, 1894

- Aepyornis maximus Hilaire, 1851 (Giant elephant-bird)

- Aepyornis cursor Milne-Edwards & Grandidier, 1894

- ?Aepyornis intermedius

- Aepyornis medius Milne-Edwards & Grandidier, 1866

The nominal species Aepyornis titan Andrews, 1894 was placed in the separate genus Vorombe by Hansford and Turvey (2018), with A. ingens a synonym of titan. Aepyornis grandidieri Rowley, 1867 is an ootaxon known only from an eggshell fragment and hence a nomen dubium. Hansford and Truvey (2018) also found Aepyornis modestus a senior synonym of all Mullerornis nominal species, making modestus the epithet of the Mullerornis type species.[2]

Evolution

Like the cassowaries, ostriches, rheas, emu and kiwis, Aepyornis was a ratite; it could not fly, and its breast bone had no keel. Because Madagascar and Africa separated before the ratite lineage arose,[5] Aepyornis has been thought to have dispersed and become flightless and gigantic in situ.[6] More recently, it has been deduced from DNA sequence comparisons that the closest living relatives of elephant birds are the New Zealand kiwis,[7] indicating that the ancestors of elephant birds dispersed to Madagascar from Australasia.

Etymology

Aepyornis maximus is commonly known as the 'elephant bird', a term that apparently originated from Marco Polo's account of the rukh in 1298, although he was apparently referring to an eagle-like bird strong enough to "seize an elephant with its talons".[8] Sightings of eggs of elephant birds by early sailors (e.g. text on the Fra Mauro map of 1467–69, if not attributable to ostriches) could also have been erroneously attributed to a giant raptor from Madagascar. The legend of the roc could also have originated from sightings of such a giant subfossil eagle related to the African crowned eagle, which has been described in the genus Stephanoaetus from Madagascar,[9] being large enough to carry off large primates; today, lemurs still retain a fear of aerial predators such as these. Another might be the perception of ratites retaining neotenic features and thus being mistaken for enormous chicks of a presumably more massive bird.

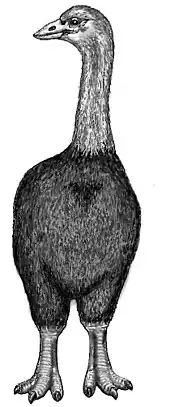

Description

Both photographed at the National Museum of Natural History in Paris

Aepyornis, which was a giant, flightless ratite native to Madagascar, has probably been extinct since at least the 11th century (AD 1000). Aepyornis was one of the world's largest birds, believed to have been up to 3 metres (9.8 ft) tall,[10] with weights in the range 210–340 kilograms (460–750 lb) for A. hildebrandti and 330–540 kilograms (730–1,200 lb) for A. maximus.[2] Remains of Aepyornis adults and eggs have been found;[11] in some cases the eggs have a circumference of over 1 m (3 ft 3 in) and a length up to 34 cm (13 in).[12] The egg volume is about 160 times greater than a chicken egg.[13]

Nocturnality

Endocasts of aepyornithid skulls have shown that these animals had poor eyesight and large olfactory bulbs, much like living kiwis. This has been interpreted as a sign that, like them, elephant birds were nocturnal.[14]

Reproduction

Occasionally, the subfossilized eggs are found intact.[15] The National Geographic Society in Washington holds a specimen of an Aepyornis egg which was given to Luis Marden in 1967. The specimen is intact and contains an embryonic skeleton of the unborn bird. Another giant Aepyornis egg is on display at the Harvard Museum of Natural History in Cambridge, MA. A cast of the Aepyornis egg is preserved at the Grant Museum of Zoology at the University of London. The BBC television personality David Attenborough owns an almost complete fossilized eggshell, which he pieced together from fragments he collected on a visit to Madagascar.

Extinction

It is widely believed that the extinction of Aepyornis was the result of human activity. The birds were initially widespread, occurring from the northern to the southern tip of Madagascar.[13] One theory states that humans hunted the elephant birds to extinction in a very short time for such a large landmass (the blitzkrieg hypothesis). There is indeed evidence that they were killed. However, their eggs may have been the most vulnerable point in their life cycle. A recent archaeological study found fragments of eggshells among the remains of human fires,[8] suggesting that the eggs regularly provided meals for entire families.

The exact time period when they died out is also not certain; tales of these giant birds may have persisted for centuries in folk memory. There is archaeological evidence of Aepyornis from a radiocarbon-dated bone at 1880 +/- 70 BP (c. AD 120) with signs of butchering, and on the basis of radiocarbon dating of shells, about 1000 BP (= c. AD 1000).[13] It is thought that Aepyornis is the Malagasy legendary extinct animal called the vorompatra (pronounced [vuˈrumpə̥ʈʂ]), Malagasy for "marsh bird" (vorom translates to "bird").[16] After many years of failed attempts, DNA molecules of Aepyornis eggs were successfully extracted by a group of international researchers and results were published in the Proceedings of the Royal Society B.[17]

It has also been suggested that the extinction was a secondary effect of human impact due to transfer of hyperdiseases from human commensals, such as chickens and guineafowl. The bones of these domesticated fowl have been found in subfossil sites on the island (MacPhee and Marx, 1997: 188), such as Ambolisatra (Madagascar), where Mullerornis sp. and Aepyornis maximus have been reported.[18]

David Attenborough in a BBC Television program transmitted in early 2011[19] said that "very few Aepyornis bones show signs of butchery, so likely there was a Malagasy native taboo against killing Aepyornis, and that is likely why Aepyornis survived so long after Man arrived there". But that does not say anything about whether the natives took so many Aepyornis eggs that the species died out.

Footnotes

- Brands, S. 2008

- Hansford, J. P.; Turvey, S. T. (26 September 2018). "Unexpected diversity within the extinct elephant birds (Aves: Aepyornithidae) and a new identity for the world's largest bird". Royal Society Open Science. 5 (9): 181295. Bibcode:2018RSOS....581295H. doi:10.1098/rsos.181295. PMC 6170582. PMID 30839722.

- Brodkorb, P. (1963)

- Julian P. Hume; Michael Walters (2012). Extinct birds. T&AD Poyser. p. 544. ISBN 978-1408158616.

- Yoder, A. D. & Nowak, M. D. (2006)

- van Tuinen, M. et al. (1998)

- Mitchell, K. J.; Llamas, B.; Soubrier, J.; Rawlence, N. J.; Worthy, T. H.; Wood, J.; Lee, M. S. Y.; Cooper, A. (23 May 2014). "Ancient DNA reveals elephant birds and kiwi are sister taxa and clarifies ratite bird evolution" (PDF). Science. 344 (6186): 898–900. Bibcode:2014Sci...344..898M. doi:10.1126/science.1251981. hdl:2328/35953. PMID 24855267. S2CID 206555952.

- Pearson and Godden (2002)

- Goodman, S. M. (1994)

- Davies, S. J. J. F. (2003)

- Morris, P (2014). "Giant eggs - a weak link? Or 'Life at the eggstreme'". The Linnean Newsletter. 30 (2): 33–36.

- Mlíkovsky, J. (2003)

- Hawkins, A. F. A. & Goodman, S. M. (2003)

- Torres, Christopher R.; Clarke, Julia A. (2018). "Nocturnal giants: evolution of the sensory ecology in elephant birds and other palaeognaths inferred from digital brain reconstructions". Proc. R. Soc. B. 285 (1890): 20181540. doi:10.1098/rspb.2018.1540. PMC 6235046. PMID 30381378.

- BBC News (2009)

- Vorompatra Central (2005)

- Ghosh, Pallab (2010)

- Goodman, S. M. & Rakotozafy, L. M. A. (1997)

- Attenborough and the Giant Egg, BBC One, 8 to 9 pm, Wednesday 2 March 2011

References

- BBC News (25 March 2009). "One minute world news". Day in Pictures. BBC News. Archived from the original on 27 March 2009. Retrieved 26 March 2009.

- Brands, Sheila J. (1989). "The Taxonomicon : Taxon: Order Aepyornithiformes". Zwaag, Netherlands: Universal Taxonomic Services. Archived from the original on 21 April 2008. Retrieved 21 Jan 2010.

- Brodkorb, Pierce (1963). "Catalogue of Fossil Birds Part 1 (Archaeopterygiformes through Ardeiformes)" (PDF). Bulletin of the Florida State Museum, Biological Sciences. 7 (4): 179–293.

- Cooper, A.; Lalueza-Fox, C.; Anderson, S.; Rambaut, A.; Austin, J.; Ward, R. (8 February 2001). "Complete Mitochondrial Genome Sequences of Two Extinct Moas Clarify Ratite Evolution". Nature. 409 (6821): 704–707. Bibcode:2001Natur.409..704C. doi:10.1038/35055536. PMID 11217857.

- Davies, S.J.J.F. (2003). "Elephant birds (Aepyornithidae)". In Hutchins, Michael (ed.). Grzimek's Animal Life Encyclopedia. 8 Birds I Tinamous and Ratites to Hoatzins (2 ed.). Farmington Hills, MI: Gale Group. pp. 103–104. ISBN 978-0-7876-5784-0.

- Ghosh, Pallab (10 March 2010). "Ancient eggshell yields its DNA". BBC News. Archived from the original on 23 March 2010. Retrieved 23 April 2010.

- Goodman, Steven M. (1994). "Description of a new species of subfossil eagle from Madagascar: Stephanoaetus (Aves: Falconiformes) from the deposits of Ampasambazimba". Proceedings of the Biological Society of Washington (107): 421–428.

- Goodman, S. M.; Rakotozafy, L. M. A. (1997). "Subfossil birds from coastal sites in western and southwestern Madagascar". In Goodman, S. M.; Patterson, B. D. (eds.). Natural Change and Human Impact in Madagascar. Washington, DC: Smithsonian Institution Press. pp. 257–279. ISBN 978-1-56098-683-6.

- Hawkins, A. F. A.; Goodman, S. M. (2003). Goodman, S. M.; Benstead, J. P. (eds.). The Natural History of Madagascar. University of Chicago Press. pp. 1026–1029. ISBN 978-0-226-30307-9.

- Hay, W. W.; DeConto, R. M.; Wold, C. N.; Wilson, K. M.; Voigt, S. (1999). "Alternative global Cretaceous paleogeography". In Barrera, E.; Johnson, C. C. (eds.). Evolution of the Cretaceous Ocean Climate System. Boulder, CO: Geological Society of America. pp. 1–47. ISBN 978-0-8137-2332-7.

- Mlíkovsky, J. (2003). "Eggs of extinct aepyornithids (Aves: Aepyornithidae) of Madagascar: size and taxonomic identity". Sylvia. 39: 133–138.

- Pearson, Mike Parker; Godden, K. (2002). In search of the Red Slave: Shipwreck and Captivity in Madagascar. Stroud, Gloucestershire: The History Press. ISBN 978-0-7509-2938-7.

- van Tuinen, Marcel; Sibley, Charles G.; Hedges, S. Blair (1998). "Phylogeny and Biogeography of Ratite Birds Inferred from DNA Sequences of the Mitochondrial Ribosomal Genes" (PDF). Molecular Biology and Evolution. 15 (4): 370–376. doi:10.1093/oxfordjournals.molbev.a025933. PMID 9549088.

- "Vorompatra". 2005. Archived from the original on 27 October 2009.

- Yoder, Anne D.; Nowak, Michael D. (2006). "Has Vicariance or Dispersal Been the Predominant Biogeographic Force in Madagascar? Only Time Will Tell". Annual Review of Ecology, Evolution, and Systematics. 37: 405–431. doi:10.1146/annurev.ecolsys.37.091305.110239.