Agathocles of Bactria

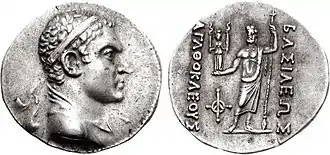

Agathocles Dikaios (Greek: Ἀγαθοκλῆς ὁ Δίκαιος; epithet meaning: "the Just") was a Greco-Bactrian/Indo-Greek king, who reigned between around 190 and 180 BC. He might have been a son of Demetrius and one of his sub-kings in charge of the Paropamisade between Bactria and Indus-Ganges plains. In that case, he was a grandson of Euthydemus whom he qualified on his coins as Βασιλεὺς Θεός, Basileus Theos (Greek for "God-King").

| Agathocles "the Just" (Δίκαιος) | |

|---|---|

Portrait of Agathocles | |

| Indo-Greek king | |

| Reign | 190–180 BC |

| Predecessor | Pantaleon |

| Successor | Apollodotus I or Antimachus I |

| Dynasty | Euthydemid |

| Father | Demetrius I |

Agathocles was contemporary with or a successor of king Pantaleon. He seems to have been attacked and killed by the usurper Eucratides, who took control of the Greco-Bactrian territory. Little is known about him, apart from his extensive coinage.

Pedigree coinage

Agathocles issued a series of "pedigree" dynastic coins, probably with the intent to advertise his lineage and legitimize his rule, linking him to Alexander the Great, a king referred to as Antiochus Nikator (Greek: "Νικάτωρ" "Victorious", probably intended to be Antiochus III), the founder of the Greco-Bactrian kingdom Diodotus and his son Diodotus II, Euthydemus, Demetrius and Pantaleon. On these coins, Agathocles labels himself ΔΙΚΑΙΟΥ, "The Just".

Agathocles commemorative coin for Alexander the Great. With Greek legends ΒΑΣΙΛΕΥΟΝΤΟΣ ΑΓΑΘΟΚΛΕΟΥΣ ΔΙΚΑΙΟΥ "Of Reign Agathocles the Just" and ΑΛΕΞΑΝΔΡΟΥ ΤΟΥ ΦΙΛΙΠΠΟΥ "Alexander son of Phillip".

Agathocles commemorative coin for Alexander the Great. With Greek legends ΒΑΣΙΛΕΥΟΝΤΟΣ ΑΓΑΘΟΚΛΕΟΥΣ ΔΙΚΑΙΟΥ "Of Reign Agathocles the Just" and ΑΛΕΞΑΝΔΡΟΥ ΤΟΥ ΦΙΛΙΠΠΟΥ "Alexander son of Phillip". Agathocles commemorative coin for Diodotus I in the name of Antiochus II.

Agathocles commemorative coin for Diodotus I in the name of Antiochus II. Agathocles commemorative coin for Euthydemus I. With Greek legends ΒΑΣΙΛΕΥΟΝΤΟΣ ΑΓΑΘΟΚΛΕΟΥΣ ΔΙΚΑΙΟΥ "Of Reign Agathocles the Just" and ΕΥΘΥΔΗΜΟΥ ΘΕΟΥ "Euthydemus God".

Agathocles commemorative coin for Euthydemus I. With Greek legends ΒΑΣΙΛΕΥΟΝΤΟΣ ΑΓΑΘΟΚΛΕΟΥΣ ΔΙΚΑΙΟΥ "Of Reign Agathocles the Just" and ΕΥΘΥΔΗΜΟΥ ΘΕΟΥ "Euthydemus God". Agathocles commemorative coin for Demetrius. With Greek legends ΒΑΣΙΛΕΥΟΝΤΟΣ ΑΓΑΘΟΚΛΕΟΥΣ ΔΙΚΑΙΟΥ "Of Reign Agathocles the Just" and ΔΗΜΗΤΡΙΟΥ ΑΝΙΚΗΤΟΥ "Demetrius Invincible".

Agathocles commemorative coin for Demetrius. With Greek legends ΒΑΣΙΛΕΥΟΝΤΟΣ ΑΓΑΘΟΚΛΕΟΥΣ ΔΙΚΑΙΟΥ "Of Reign Agathocles the Just" and ΔΗΜΗΤΡΙΟΥ ΑΝΙΚΗΤΟΥ "Demetrius Invincible". Agathocles commemorative coin for Pantaleon.

Agathocles commemorative coin for Pantaleon.

Dynast or usurper?

Obv: – Greek inscription reads: ΔΗΜΗΤΡΙΟΥ ΑΝΙΚΗΤΟΥ i.e. "of Demetrius the Invincible".

The pedigree coinage has been seen as a token of his ancestry, but a critical view might be considered. All the associations provide a contradictory image. The Euthydemid kings (Demetrius and Euthydemus) are not known to be related to Diodotus – in fact, Euthydemus I overthrew Diodotus II. The Seleucids were enemies of the Euthydemids as well – king Antiochus III had besieged Bactra for almost three years before claiming victory over Euthydemus I. However, Antiochus III did not take the territory and after Euthydemus I sent his son Demetrius in an envoy to him, he recognized them as the rightful kings in Bactria. Antiochus III is known to have used the epithet "Nikator" ("Νικάτωρ" Greek for "Victorious").[2]

Finally, the association with Alexander was a standard move for usurpers in the Hellenistic world, such as the pseudo-Seleucids Alexander Balas and the Syrian general Diodotus Tryphon.

All in all, the coins might well support the view of a usurper, or more probable a member of a minor branch of a dynasty, anxious to gather support from all quarters with his various memorial coins. However, the similarities between his coinage and that of Pantaleon make it probable that Agathocles was indeed a relative of the latter, who in that case might have been a usurper as well.

- I) Pedigree coin of Agathocles with Alexander the Great.

Obverse – Greek inscription reads: ΑΛΕΞΑΝΔΡΟΥ ΤΟΥ ΦΙΛΙΠΠΟΥ i.e. "of Alexander son of Philip".

Reverse – Greek inscription reads: ΒΑΣΙΛΕΥΟΝΤΟΣ ΑΓΑΘΟΚΛΕΟΥΣ ΔΙΚΑΙΟΥ i.e. "of Reign Agathocles the Just".

- II) Pedigree coin of Agathocles with Diodotus the Saviour.

Obverse – Greek inscription reads: ΔΙΟΔΟΤΟΥ ΣΩΤΗΡΟΣ i.e. "of Diodotus the Saviour".

Reverse – Greek inscription reads: ΒΑΣΙΛΕΥΟΝΤΟΣ ΑΓΑΘΟΚΛΕΟΥΣ ΔΙΚΑΙΟΥ i.e. "of Reign Agathocles the Just".

Nickel coins

Also, Agathocles and Pantaleon, along with their contemporary Euthydemus II, are unique in the ancient world, in that they were the first in the world to issue copper-nickel (75/25 ratio) coins1, an alloy technology only known by the Chinese at the time (some weapons from the Warring States period were in copper-nickel alloy2). These coins are indicative of the existence of trade links with China around that time (see Greco-Bactrian kingdom). Copper-nickel would not be used again in coinage until the 19th century in the United States.

These coins used the symbolism of Dionysos with a thyrsus over his left shoulder and his panther, which were his type for smaller coinage.[3][4]

Bilingual coinage

1. Zeus standing with goddess Hecate.[7] Greek: "King Agathokles".

2. Deity wearing a long himation with a volume on the head, arm partly bent, and contrapposto pose. Greek: "King Agathokles".[7] This coin is in bronze.

3. Hindu god Balarama-Samkarshana with attributes. Greek: "King Agathokles".[8]

4. Hindu god Vasudeva-Krishna with attributes.[8] Brahmi: “Rajane Agathukleyasa”, "King Agathokles".

5. Goddess Lakshmi, holding a lotus in her right hand.[9] Brahmi: “Rajane Agathukleyasa”, "King Agathokles".

At the same time, Agathocles issued an intriguing range of bilingual coinage, displaying what seems to be Buddhist as well as Hindu symbolism. The coins, manufactured according to the Indian standard, using either Brahmi, Greek or Kharoshthi (a first in the Greek world), and displaying symbols of the various faiths in India, tend to indicate a considerable willingness to accommodate local languages and beliefs, to an extent unseen in subsequent Indo-Greek kings. They may be indicative of the considerable efforts of the first Indo-Greek kings to secure support from Indian populations and avoid being perceived as invaders, efforts which may have subsided once the Indo-Greek kingdoms were more securely in place.

Buddhist coinage

The Buddhist coinage of Agathocles is in the Indian standard (square or round copper coins) and depicts Buddhist symbols such as the stupa (or arched-hill symbol), the "tree in railing" (another Buddhist symbol)[10] or the lion. These coins sometimes use Brahmi, and sometimes Kharoshthi, whereas later Indo-Greek kings only used Kharoshthi. Lakshmi appears in several of these coins, a Goddess of abundance and fortune for Hindus and early Buddhists.

Buddhist coin of Agathocles, with stupa surmounted by a star, and vegetal symbol.

Buddhist coin of Agathocles, with stupa surmounted by a star, and vegetal symbol. A six-arched hill symbol surmounted by a star. Kharoshthi legend Akathukreyasa "Agathocles". Tree-in-railing, Kharoshthi legend Hirañasame.[11][12]

A six-arched hill symbol surmounted by a star. Kharoshthi legend Akathukreyasa "Agathocles". Tree-in-railing, Kharoshthi legend Hirañasame.[11][12] Agathokles coin Rajaye Agathukleya (Brahmi script).

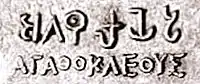

Agathokles coin Rajaye Agathukleya (Brahmi script).

Hinduist coinage

'Obv Balarama-Samkarshana with Greek legend: ΒΑΣΙΛΕΩΣ ΑΓΑΘΟΚΛΕΟΥΣ (Basileōs Agathokleous).

Rev Vasudeva-Krishna with Brahmi legend:𑀭𑀚𑀦𑁂 𑀅𑀕𑀣𑀼𑀼𑀓𑁆𑀮𑁂𑀬𑁂𑀲 Rajane Agathukleyesa "King Agathocles".

The Hinduist coins of Agathocles are few but spectacular. Six Indian-standard silver drachmas were discovered at Ai-Khanoum in 1970, which depict Hindu deities.[13] These coins, discovered on 3 October 1970 hidden in a pilgrim’s water-vessel in a room of the administrative quarter of the Greco-Bactrian city of Ai-Khanoum, are key to the understanding of the evolution of Vaisnava imagery in India.[14]

These seem to be the first known representations of Vedic deities on coins, and they display early Avatars of Vishnu: Balarama-Sankarshana with attributes consisting of the Gada mace and the plow, and Vasudeva-Krishna with the Vishnu attributes of the Shankha (a pear-shaped case or conch) and the Sudarshana Chakra wheel.[13][14] According to Bopearachchi, the headdress is actually a misrepresentation of a shaft with a half-moon parasol on top (chattra), as seen in later statues of Bodhisattvas in Mathura. It is therefore thought that sculptures or images, predating the coins but now lost, served as models to the engravers.[14]

The frontal pose of these deities is totally uncharacteristic of the general depiction of Gods on Greek coins, who are generally shown in three-quarter postures. The sideways disposition of the feet is also characteristic of early India sculptures, as seen in the stupas of Bharhut or Sanci. This leads specialists to think that these images are the work of Indian engravers, who were familiar with the style and conventions of archaic Indian art.[14]

The dancing girls on some of the coins of Agathocles and Pantaleon are also sometimes considered as representations of Lakshmi, the consort of Vishnu, but also a Goddess of abundance and fortune for Buddhists, or Subhadra, the sister of Krishna and Balarama. She is also seen in the Post-Mauryan coinage of Gandhara, on a Taxilan coin which is thought to have been minted by Demetrius I following his invasion.[14]

These coins from Ai-Khanoum are a precious indication of the forms taken by the Bhagavata cult and Vaishnavism in early India, and shows that this cult was already popular in the area of Gandhara around the 2nd century BCE. The first known inscription related to the Bhagavata cult was also made by an Indo-Greek, an ambassador of king Antialcidas, who wrote a dedication on the Besnagar pillar in the 2nd century CE.[14]

This popularity suffered a drastic decline when the Kushan Emperor Vima Kadphises proclaimed on his coins in the 1st century AD his worship of Shiva.[14]

Decipherment of the Brahmi script

From 1834, some attempts were made to decipher the Brahmi script, the main script used in old Indian inscriptions such as the Edicts of Ashoka, and which had become extinct since the 5th century CE. Some attempts by Rev. J. Stevenson were made to identify characters from the Karla Caves (circa 1st century CE) based on their similarities with the Gupta script of the Samudragupta inscription of the Allahabad pillar (4th century CE) which had just been deciphered, but this led to a mix of good (about 1/3) and bad guesses, which did not permit proper decipherment of the Brahmi.[16][17]

The first successful attempts at deciphering the ancient Brahmi script of the 3rd-2nd centuries BCE were made in 1836 by Norwegian scholar Christian Lassen, who used the bilingual Greek-Brahmi coins of Indo-Greek kings Agathocles and Pantaleon to correctly and securely identify several Brahmi letters.[15] The task was then completed by James Prinsep, an archaeologist, philologist, and official of the East India Company, who was able to identify the rest of the Brahmi characters, with the help of Major Cunningham.[15][18] In a series of results that he published in March 1838 Prinsep was able to translate the inscriptions on a large number of rock edicts found around India, and provide, according to Richard Salomon, a "virtually perfect" rendering of the full Brahmi alphabet.[19][20]

See also

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Agathocles of Bactria. |

Notes

- Foreign Influence on Ancient India, Krishna Chandra Sagar, Northern Book Centre, 1992

- Chronographia, John of Malalas

- Holt, Frank Lee (1988). Alexander the Great and Bactria: The Formation of a Greek Frontier in Central Asia. Brill Archive. p. 2. ISBN 9004086129.

- Kim, Hyun Jin; Vervaet, Frederik Juliaan; Adali, Selim Ferruh (2017). Eurasian Empires in Antiquity and the Early Middle Ages: Contact and Exchange between the Graeco-Roman World, Inner Asia and China. Cambridge University Press. p. 267. ISBN 9781108121316.

- Holt, Frank Lee (1988). Alexander the Great and Bactria: The Formation of a Greek Frontier in Central Asia. Brill Archive. ISBN 9004086129.

- Osmund Bopearachchi "Monnaies Gréco-Bactriennes et Indo-Grecques" Bibliothèque Nationale 1991, p. 172-180

- Osmund Bopearachchi, Catalogue raisonné, p. 172-175

- P. Bernard, Revue Numismatique 1974 p. 7-41

- P. Bernard, Revue Numismatique 1974 p. 23

- Krishan, Yuvraj; Tadikonda, Kalpana K. (1996). The Buddha Image: Its Origin and Development. Bharatiya Vidya Bhavan. p. 22. ISBN 9788121505659.

- Monnaies Gréco-Bactriennes et Indo-Grecques, Bopearachchi, p.176

- Krishan, Yuvraj; Tadikonda, Kalpana K. (1996). The Buddha Image: Its Origin and Development. Bharatiya Vidya Bhavan. p. 22. ISBN 978-81-215-0565-9.

- Iconography of Balarāma, Nilakanth Purushottam Joshi, Abhinav Publications, 1979, p.22

- Osmund Bopearachchi, 2016, Emergence of Viṣṇu and Śiva Images in India: Numismatic and Sculptural Evidence

- Ray, Himanshu Prabha (2017). Buddhism and Gandhara: An Archaeology of Museum Collections. Taylor & Francis. p. 181. ISBN 9781351252744.

- Journal of the Asiatic Society of Bengal. Calcutta : Printed at the Baptist Mission Press [etc.] 1834. pp. 495–499.

- Salomon, Richard (1998). Indian Epigraphy: A Guide to the Study of Inscriptions in Sanskrit, Prakrit, and the other Indo-Aryan Languages. Oxford University Press. p. 206. ISBN 9780195356663.

- More details about Buddhist monuments at Sanchi Archived 2011-07-21 at the Wayback Machine, Archaeological Survey of India, 1989.

- Journal of the Asiatic Society of Bengal. Calcutta : Printed at the Baptist Mission Press [etc.] 1838. pp. 219–285.

- Salomon, Richard (1998). Indian Epigraphy: A Guide to the Study of Inscriptions in Sanskrit, Prakrit, and the other Indo-Aryan Languages. Oxford University Press. p. 208. ISBN 9780195356663.

References

- The Greeks in Bactria and India, W. W. Tarn, Cambridge University Press

- Bactria – the history of a forgotten empire, H. G. Rawlinson, Probhstain & co, London (1912) (Internet Archive)

External links

- Coins of Agatocles

- More coins of Agathocles

- Catalogue of the coins of Agathocles

- Copper-Nickel coinage in Greco-Bactria

- Ancient Chinese weapons

- A halberd of copper-nickel alloy, from the Warring States Period

| Preceded by Demetrius I |

Greco-Bactrian king (in Paropamisade) 190-180 BCE |

Succeeded by Apollodotus I |

- O. Bopearachchi, "Monnaies gréco-bactriennes et indo-grecques, Catalogue raisonné", Bibliothèque Nationale, Paris, 1991, p.453

- Quintanilla, Sonya Rhie (2 April 2019). "History of Early Stone Sculpture at Mathura: Ca. 150 BCE - 100 CE". BRILL – via Google Books.