Lakshmi

Lakshmi (/ˈlʌkʃmi/;[3][nb 1] Sanskrit: लक्ष्मी Lakṣmī, lit. 'goddess who leads to one's goal'), also known as Sri (Sanskrit: श्री, IAST: Śrī, lit. 'Noble goddess'),[5] is one of the principal goddesses in Hinduism. She is the goddess of wealth, fortune, love, beauty, joy and prosperity,[6] and associated with Maya ("Illusion"). Along with Parvati and Saraswati, she forms the trinity of Hindu goddesses (Tridevi).[7]

| Lakshmi | |

|---|---|

| Member of Tridevi | |

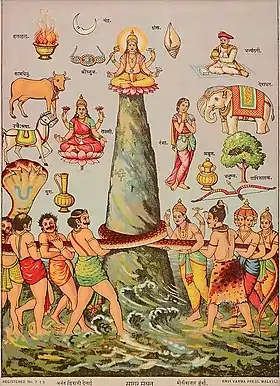

Raja Ravi Varma's Gaja Lakshmi | |

| Other names | Sri, Narayani, Bhagavati, Padmā, Kamalā, Vaishnavi |

| Devanagari | लक्ष्मी |

| Affiliation | Devi, Tridevi, Ashta Lakshmi, Durga |

| Abode | Vaikuntha |

| Mantra | ।।ॐ श्रीं श्रियें नमः ।। |

| Symbols | Padma (Lotus), gold, coins, elephants |

| Mount | Owl and Elephant |

| Festivals | Diwali (Lakshmi Puja), Navratri, Sharad Purnima, Varalakshmi Vratam |

| Personal information | |

| Siblings | Jyestha or Alakshmi |

| Consort | Vishnu[2] |

| Children | Kamadeva (according to some texts) |

Within the Goddess-oriented Shaktism, Lakshmi is venerated as a principle aspect of the Mother goddess.[8][9] Lakshmi is both the wife and divine energy (shakti) of the Hindu god Vishnu, the Supreme Being of Vaishnavism; she is also the Supreme Goddess in the sect and assists Vishnu to create, protect and transform the universe.[2][10][9][11] Whenever Vishnu descended on the earth as an avatar, Lakshmi accompanied him as wife, for example as Sita and Rukmini as consorts of Vishnu's avatars Rama and Krishna respectively.[5][9] The eight prominent manifestations of Lakshmi, the Ashtalakshmi symbolize the eight sources of wealth.[12]

Lakshmi is depicted in Indian art as an elegantly dressed, prosperity-showering golden-coloured woman with an owl as her vehicle, signifying the importance of economic activity in maintenance of life, her ability to move, work and prevail in confusing darkness.[13] She typically stands or sits on a lotus pedestal, while holding a lotus in her hand, symbolizing fortune, self-knowledge, and spiritual liberation.[14][15] Her iconography shows her with four hands, which represent the four aspects of human life important to Hindu culture: dharma, kāma, artha, and moksha.[16][17]

Archaeological discoveries and ancient coins suggest the recognition and reverence for Lakshmi existing by the 1st millennium BCE.[18][19] Lakshmi's iconography and statues have also been found in Hindu temples throughout Southeast Asia, estimated to be from the second half of the 1st millennium CE.[20][21] The festivals of Diwali and Sharad Purnima (Kojagiri Purnima) are celebrated in her honor.[22]

Etymology and epithets

Lakshmi in Sanskrit is derived from the root word lakṣ (लक्ष्) and lakṣa (लक्ष), meaning 'to perceive, observe, know, understand' and 'goal, aim, objective', respectively.[23] These roots give Lakshmi the symbolism: know and understand your goal.[24] A related term is lakṣaṇa, which means 'sign, target, aim, symbol, attribute, quality, lucky mark, auspicious opportunity'.[25]

_(6843511981).jpg.webp)

Lakshmi has numerous epithets and numerous ancient Stotram and Sutras of Hinduism recite her various names:[26][27]

- Padmā: She of the lotus (she who is mounted upon or dwelling in a lotus)

- Kamalā or Kamalatmika: She of the lotus

- Padmapriyā: Lotus-lover

- Padmamālādhāra Devī: Goddess bearing a garland of lotuses

- Padmamukhī: Lotus-faced (she whose face is as like as a lotus)

- Padmākṣī: Lotus-eyed (she whose eyes are as beautiful as a lotus)

- Padmahasta: Lotus-hand (she whose hand is holding [a] lotus[es])

- Padmasundarī: She who is as beautiful as a lotus

- Sri: Radiance, eminence, splendor, wealth

- Śrījā: Jatika of Sri

- Viṣṇupriyā: Lover of Vishnu (she who is the beloved of Vishnu)

- Ulūkavāhinī: Owl-mounted (she who is riding an owl)

- Nandika: The one who gives pleasure, the vessel made up of clay and Vishnupriya (she who is the beloved of Vishnu)

Her other names include:[26] Aishwarya, Akhila, Anagha, Anumati, Apara, Aruna, Atibha, Avashya, Bala, Bhargavi, Bhudevi, Chakrika, Chanchala, Devi, Haripriya, Indira, Jalaja, Jambhavati, Janamodini, Jyoti, Jyotsna, Kalyani, Kamalika, Ketki, Kriyalakshmi, Kuhu, Lalima, Madhavi, Madhu, Malti, Manushri, Nandika, Nandini, Nila Devi, Nimeshika, Parama, Prachi, Purnima, Radha, Ramaa, Rukmini, Samruddhi, Satyabhama, Shreeya, Sita, Smriti, Sridevi, Sujata, Swarna Kamala, Taruni, Tilottama, Tulasi, Vaishnavi, Vasuda, Vedavati, Vidya, and Viroopa.

Symbolism and iconography

Lakshmi is a member of the Tridevi, the triad of great goddesses. She represents the Rajas guna, and the Iccha-shakti.[29][30] The image, icons, and sculptures of Lakshmi are represented with symbolism. Her name is derived from Sanskrit root words for knowing the goal and understanding the objective.[24] Her four arms are symbolic of the four goals of humanity that are considered good in Hinduism: dharma (pursuit of ethical, moral life), artha (pursuit of wealth, means of life), kama (pursuit of love, emotional fulfillment), and moksha (pursuit of self-knowledge, liberation).[17][31]

In Lakshmi's iconography, she is either sitting or standing on a lotus and typically carrying a lotus in one or two hands. The lotus carries symbolic meanings in Hinduism and other Indian traditions. It symbolizes knowledge, self-realization, and liberation in the Vedic context, and represents reality, consciousness, and karma ('work, deed') in the Tantra (Sahasrara) context.[32] The lotus, a flower that blooms in clean or dirty water, also symbolizes purity regardless of the good or bad circumstances in which it grows. It is a reminder that good and prosperity can bloom and not be affected by evil in one's surroundings.[33][34]

Below, behind, or on the sides, Lakshmi is very often shown with one or two elephants, known as Gajalakshmi, and occasionally with an owl.[13] Elephants symbolize work, activity, and strength, as well as water, rain and fertility for abundant prosperity.[35] The owl signifies the patient striving to observe, see, and discover knowledge, particularly when surrounded by darkness. As a bird reputedly blinded by daylight, the owl also serves as a symbolic reminder to refrain from blindness and greed after knowledge and wealth have been acquired.[36] The Gupta period sculpture used to associate lion with Lakshmi but was later attributed to Durga or a combined form of both goddesses.[37][38][39][40] Lion is also associated with Veera Lakshmi, who is one of the Ashtalakshmi.[41]

In some representations, wealth either symbolically pours out from one of her hands or she simply holds a jar of money. This symbolism has a dual meaning: wealth manifested through Lakshmi means both materials as well as spiritual wealth.[32] Her face and open hands are in a mudra that signifies compassion, giving or dāna ('charity').[31]

Lakshmi typically wears a red dress embroidered with golden threads, which symbolizes fortune and wealth. She, goddess of wealth and prosperity, is often represented with her husband Vishnu, the god who maintains human life filled with justice and peace. This symbolism implies wealth and prosperity are coupled with the maintenance of life, justice, and peace.[32]

In Japan, where Lakshmi is known as Kisshōten, she is commonly depicted with the Nyoihōju gem (如意宝珠) in her hand.

In Hindu literature

Lakshmi is one of the trinity of Hindu goddesses. Her iconography is found in ancient and modern Hindu temples. | |||||||

Vedas and Brahmanas

The meaning and significance of Lakshmi evolved in ancient Sanskrit texts.[42] Lakshmi is mentioned once in Rigveda, in which the name is used to mean 'kindred mark, sign of auspicious fortune'.

भद्रैषां लक्ष्मीर्निहिताधि वाचि |

"an auspicious fortune is attached to their words" |

| —Rig Veda, x.71.2 | —translated by John Muir[42] |

In Atharva Veda, transcribed about 1000 BCE, Lakshmi evolves into a complex concept with plural manifestations. Book 7, Chapter 115 of Atharva Veda describes the plurality, asserting that a hundred Lakshmis are born with the body of a mortal at birth, some good, Punya ('virtuous') and auspicious, while others bad, paapi ('evil') and unfortunate. The good are welcomed, while the bad urged them to leave.[42] The concept and spirit of Lakshmi and her association with fortune and the good is significant enough that Atharva Veda mentions it in multiple books: for example, in Book 12, Chapter 5 as Punya Lakshmi.[43] In some chapters of Atharva Veda, Lakshmi connotes the good, an auspicious sign, good luck, good fortune, prosperity, success, and happiness.[1]

Later, Lakshmi is referred to as the goddess of fortune, identified with Sri and regarded as the wife of Viṣṇu (Nārāyaṇa).[1] For example, in Shatapatha Brahmana, variously estimated to be composed between 800 BCE and 300 BCE, Sri (Lakshmi) is part of one of many theories, in ancient India, about the creation of the universe. In Book 9 of Shatapatha Brahmana, Sri emerges from Prajapati, after his intense meditation on the creation of life and nature of the universe. Sri is described as a resplendent and trembling woman at her birth with immense energy and powers.[42] The gods are bewitched, desire her, and immediately become covetous of her. The gods approach Prajapati and request permission to kill her and then take her powers, talents, and gifts. Prajapati refuses, tells the gods that males should not kill females and that they can seek her gifts without violence.[44] The gods then approach Lakshmi, deity Agni gets food, Soma gets kingly authority, Varuna gets imperial authority, Mitra acquires martial energy, Indra gets force, Brihaspati gets priestly authority, Savitri acquires dominion, Pushan gets splendour, Saraswati takes nourishment and Tvashtri gets forms.[42] The hymns of Shatapatha Brahmana thus describe Sri as a goddess born with and personifying a diverse range of talents and powers.

According to another legend, she emerges during the creation of universe, floating over the water on the expanded petals of a lotus flower; she is also variously regarded as wife of Dharma, mother of Kāma, sister or mother of Dhātṛ and Vidhātṛ, wife of Dattatreya, one of the nine Shaktis of Viṣṇu, a manifestation of Prakṛti as identified with Dākshāyaṇī in Bharatasrama and as Sita, wife of Rama.[1][45]:103–12

Epics

In the Epics of Hinduism, such as in Mahabharata, Lakshmi personifies wealth, riches, happiness, loveliness, grace, charm, and splendor.[1] In another Hindu legend, about the creation of the universe as described in Ramayana,[46] Lakshmi springs with other precious things from the foam of the ocean of milk when it is churned by the gods and demons for the recovery of Amṛta. She appeared with a lotus in her hand and so she is also called Padmā.[1][45]:108–11

Sita, the female protagonist of the Ramayana and her husband, the god-king Rama are considered as avatars of Lakshmi and Vishnu respectively. Similarly, Rukmini, the queen-consort of Vishnu's avatar Krishna from the Mahabharata, is regarded as an avatar of the goddess.

Upanishads

Shakta Upanishads are dedicated to the Trinity (Tridevi) of goddesses—Lakshmi, Saraswati and Parvati. Saubhagyalakshmi Upanishad describes the qualities, characteristics, and powers of Lakshmi.[47] In the second part of the Upanishad, the emphasis shifts to the use of yoga and transcendence from material craving to achieve spiritual knowledge and self-realization, the true wealth.[48][49] Saubhagya-Lakshmi Upanishad synonymously uses Sri to describe Lakshmi.[50]

Stotram and sutras

Numerous ancient Stotram and Sutras of Hinduism recite hymns dedicated to Lakshmi.[26] She is a major goddess in Puranas and Itihasa of Hinduism. In ancient scriptures of India, all women are declared to be embodiments of Lakshmi. For example:[26]

Every woman is an embodiment of you.

You exist as little girls in their childhood,

As young women in their youth

And as elderly women in their old age.— Sri Kamala Stotram

Every woman is an emanation of you.

— Sri Daivakrta Laksmi Stotram

Ancient prayers dedicated to Lakshmi seek both material and spiritual wealth in prayers.[26]

Through illusion,

A person can become disconnected,

From his higher self,

Wandering about from place to place,

Bereft of clear thought,

Lost in destructive behavior.

It matters not how much truth,

May shine forth in the world,

Illuminating the entire creation,

For one cannot acquire wisdom,

Unless it is experienced,

Through the opening on the heart....

Puranas

_in_the_Hoysaleshwara_temple_at_Halebidu.jpg.webp)

Lakshmi features prominently in Puranas of Hinduism. Vishnu Purana, in particular, dedicates many sections to her and also refers to her as Sri.[51] J. A. B. van Buitenen translates passages describing Lakshmi in Vishnu Purana:[51]

Sri, loyal to Vishnu, is the mother of the world. Vishnu is the meaning, Sri is the speech. She is the conduct, he the behavior. Vishnu is knowledge, she the insight. He is dharma, she the virtuous action. She is the earth, the earth's upholder. She is contentment, he the satisfaction. She wishes, he is the desire. Sri is the sky, Vishnu the Self of everything. He is the moon, she the light of the moon. He is the ocean, she is the shore.

Subhasita, Genomic and Didactic Literature

Lakshmi, along with Parvati and Saraswati, is a subject of extensive Subhashita, genomic and didactic literature of India.[52] Composed in the 1st millennium BC through the 16th century AD, they are short poems, proverbs, couplets, or aphorisms in Sanskrit written in a precise meter. They sometimes take the form of a dialogue between Lakshmi and Vishnu or highlight the spiritual message in Vedas and ethical maxims from Hindu Epics through Lakshmi.[52] An example Subhashita is Puranartha Samgraha, compiled by Vekataraya in South India, where Lakshmi and Vishnu discuss niti ('right, moral conduct') and rajaniti ('statesmanship' or 'right governance')—covering in 30 chapters and ethical and moral questions about personal, social and political life.[52]:22

Manifestations and aspects

Inside temples, Lakshmi is often shown together with Vishnu. In certain parts of India, Lakshmi plays a special role as the mediator between her husband Vishnu and his worldly devotees. When asking Vishnu for grace or forgiveness, the devotees often approach Him through the intermediary presence of Lakshmi.[53] She is also the personification of spiritual fulfillment. Lakshmi embodies the spiritual world, also known as Vaikuntha, the abode of Lakshmi and Vishnu (collectively called Lakshmi Narayana. Lakshmi is the embodiment of the creative energy of Vishnu,[54] and primordial Prakriti who creates the universe.[55]

According to Garuda Purana, Lakshmi is considered as Prakriti (Mahalakshmi) and is identified with three form — Sri, Bhu and Durga. The three forms consists of Satva ('goodness'),[1] rajas, and tamas ('darkness') gunas,[56] and assists Vishnu (Purusha) in creation, preservation and destruction of the entire universe. Durga form represents the power to fight, conquer and punish the demons and anti-gods.

In the Lakshmi Tantra, Lakshmi is given the status of the primordial goddess. According to the text, Durga and forms like Mahakali, Mahalakshmi and Mahasaraswati and all the Shaktis that came out of all gods such as Matrikas and Mahavidya[57] are all various forms of Goddess Lakshmi.[58] Lakshmi says that she got the name Durga after killing an asura named Durgama.[59]

Lakshmi, Saraswati, and Parvati are typically conceptualized as distinct in most of India, but in states such as West Bengal and Odisha, they are regionally believed to be forms of Durga.[60] In Hindu Bengali culture, Lakshmi, along with Saraswati, are seen as the daughters of Durga. They are worshipped during Durga Puja.[61]

In South India, Lakshmi is seen in two forms, Sridevi and Bhudevi, both at the sides of Venkateshwara, a form of Vishnu. Bhudevi is the representation and totality of the material world or energy, called the Apara Prakriti, or Mother Earth; Sridevi is the spiritual world or energy called the Prakriti].[2][62] According to Lakshmi Tantra, Nila Devi, one of the manifestations or incarnations of Lakshmi is the third wife of Vishnu.[63][64] Each goddess of the triad is mentioned in Śrī Sūkta, Bhu Sūkta and Nila Sūkta respectively.[65][66][67] This threefold goddess can be found, for example, in Sri Bhu Neela Sahita Temple near Dwaraka Tirumala, Andhra Pradesh, and in Adinath Swami Temple in Tamil Nadu.[68] In many parts of the region, Andal is considered as an incarnation of Lakshmi.[69]

Ashta Lakshmi (Sanskrit: अष्टलक्ष्मी, Aṣṭalakṣmī, 'eight Lakshmis') is a group of eight secondary manifestations of Lakshmi. The Ashta Lakshmi presides over eight sources of wealth and thus represents the eight powers of Shri Lakshmi. Temples dedicated to Ashta Lakshmi are found in Tamil Nadu, such as Ashtalakshmi Kovil near Chennai and many other states of India.[70]

| Adi Lakshmi | The First manifestation of Lakshmi |

| Dhanya Lakshmi | Granary Wealth |

| Veera Lakshmi | Wealth of Courage |

| Gaja Lakshmi | Elephants spraying water, the wealth of fertility, rains, and food.[71] |

| Santana Lakshmi | Wealth of Continuity, Progeny |

| Vidya Lakshmi | Wealth of Knowledge and Wisdom |

| Vijaya Lakshmi | Wealth of Victory |

| Dhana / Aishwarya Lakshmi | Wealth of prosperity and fortune |

Creation and legends

Devas (gods) and asuras (demons) were both mortal at one time in Hinduism. Amrita, the divine nectar that grants immortality, could only be obtained by churning Kshirasagar ('Ocean of Milk'). The devas and asuras both sought immortality and decided to churn the Kshirasagar with Mount Mandhara. The samudra manthan commenced with the devas on one side and the asuras on the other. Vishnu incarnated as Kurma, the tortoise, and a mountain was placed on the tortoise as a churning pole. Vasuki, the great venom-spewing serpent-god, was wrapped around the mountain and used to churn the ocean. A host of divine celestial objects came up during the churning. Along with them emerged the goddess Lakshmi. In some versions, she is said to be the daughter of the sea god since she emerged from the sea.[72]

In Garuda Purana, Linga Purana and Padma Purana, Lakshmi is said to have been born as the daughter of the divine sage Bhrigu and his wife Khyati and was named Bhargavi. According to Vishnu Purana, the universe was created when the devas and asuras churned the cosmic Kshirasagar. Lakshmi came out of the ocean bearing lotus, along with divine cow Kamadhenu, Varuni, Parijat tree, Apsaras, Chandra (the moon), and Dhanvantari with Amrita ('nectar of immortality'). When she appeared, she had a choice to go to Devas or Asuras. She chose Devas' side and among thirty deities, she chose to be with Vishnu. Thereafter, in all three worlds, the lotus-bearing goddess was celebrated.[51]

Worship

Many Hindus worship Lakshmi on Diwali, the festival of lights.[75] It is celebrated in autumn, typically October or November every year.[76] The festival spiritually signifies the victory of light over darkness, knowledge over ignorance, good over evil and hope over despair.[77]

Before Diwali night, people clean, renovate and decorate their homes and offices.[78] On Diwali night, Hindus dress up in new clothes or their best outfits, light up diyas (lamps and candles) inside and outside their home, and participate in family puja (prayers) typically to Lakshmi. After puja, fireworks follow,[79] then a family feast including mithai (sweets), and an exchange of gifts between family members and close friends. Diwali also marks a major shopping period, since Lakshmi connotes auspiciousness, wealth and prosperity.[80] This festival dedicated to Lakshmi is considered by Hindus to be one of the most important and joyous festivals of the year.

Gaja Lakshmi Puja is another autumn festival celebrated on Sharad Purnima in many parts of India on the full-moon day in the month of Ashvin (October).[22] Sharad Purnima, also called Kojaagari Purnima or Kuanr Purnima, is a harvest festival marking the end of monsoon season. There is a traditional celebration of the moon called the Kaumudi celebration, Kaumudi meaning moonlight.[81] On Sharad Purnima night, goddess Lakshmi is thanked and worshipped for the harvests. Vaibhav Lakshmi Vrata is observed on Friday for prosperity.[82]

Devi Lakshmi is worshipped as:

- Ambabai in the Kolhapur Shakti peetha,

- Mookambika in Kollur (Karnataka),

- Bhagavathi in Chottanikkara Temple (Kerala),

- Sri Kanaka Maha Lakshmi in Vishakhapatnam.

Hymns

Countless hymns, prayers, shlokas, stotra, songs, and legends dedicated to Mahalakshmi are recited during the ritual worship of Lakshmi.[26] These include:[83]

- Sri Lalitha Sahasranamam,

- Sri Mahalakshmi Ashtakam,

- Sri Lakshmi Sahasaranama Stotra (by Sanath kumara),

- Sri Stuti (by Sri Vedantha Desikar),

- Sri Lakshmi Stuti (by Indra),

- Sri Kanakadhāra Stotram (by Sri Adi Shankara),

- Sri Chatussloki (by Sri Yamunacharya),

- Narayani Stuti,

- Devi Mahatmyam Middle episode,

- Argala Stotra,

- Sri Lakshmi Sloka (by Bhagavan Sri Hari Swamiji), and

- Sri Sukta, which is contained in the Vedas and includes Lakshmi Gayatri Mantra ("Om Shree Mahalakshmyai ca vidmahe Vishnu patnyai ca dheemahi tanno Lakshmi prachodayat, Om").

Archaeology

_LACMA_M.85.62_(cropped).jpg.webp)

A representation of the goddess as Gaja Lakshmi or Lakshmi flanked by two elephants spraying her with water, is one of the most frequently found in archaeological sites.[18][19] An ancient sculpture of Gaja Lakshmi (from Sonkh site at Mathura) dates to the pre-Kushan Empire era.[18] Atranjikhera site in modern Uttar Pradesh has yielded terracotta plaque with images of Lakshmi dating to 2nd century BCE. Other archaeological sites with ancient Lakshmi terracotta figurines from the 1st millennium BCE include Vaisali, Sravasti, Kausambi, Campa, and Candraketugadh.[19]

The goddess Lakshmi is frequently found in ancient coins of various Hindu kingdoms from Afghanistan to India. Gaja Lakshmi has been found on coins of Scytho-Parthian kings Azes II and Azilises; she also appears on Shunga Empire king Jyesthamitra era coins, both dating to 1st millennium BCE. Coins from 1st through 4th century CE found in various locations in India such as Ayodhya, Mathura, Ujjain, Sanchi, Bodh Gaya, Kanauj, all feature Lakshmi.[84] Similarly, ancient Greco-Indian gems and seals with images of Lakshmi have been found, estimated to be from 1st-millennium BCE.[85]

A 1400-year-old rare granite sculpture of Lakshmi has been recovered at the Waghama village along Jehlum in Anantnag district of Jammu and Kashmir.[86]

The Pompeii Lakshmi, a statuette supposedly thought to be of Lakshmi found in Pompeii, Italy, dates to before the eruption of Vesuvius in 79 CE.[87]

In other religions and cultures

Jainism

Lakshmi is also an important deity in Jainism and found in Jain temples.[88][89] Some Jain temples also depict Sri Lakshmi as a goddess of artha ('wealth') and kama ('pleasure'). For example, she is exhibited with Vishnu in Parshvanatha Jain Temple at the Khajuraho Monuments of Madhya Pradesh,[90] where she is shown pressed against Vishnu's chest, while Vishnu cups a breast in his palm. The presence of Vishnu-Lakshmi iconography in a Jain temple built near the Hindu temples of Khajuraho, suggests the sharing and acceptance of Lakshmi across a spectrum of Indian religions.[90] This commonality is reflected in the praise of Lakshmi found in the Jain text Kalpa Sūtra.[91]

Buddhism

In Buddhism, Lakshmi has been viewed as a goddess of abundance and fortune, and is represented on the oldest surviving stupas and cave temples of Buddhism.[92][93] In Buddhist sects of Tibet, Nepal, and Southeast Asia, Vasudhara mirrors the characteristics and attributes of the Hindu Goddess, with minor iconographic differences.[94]

In China, Lakshmi's name is written as Lāhākxīmǐ (拉克希米; 'competed-gain hope rice'). In Tibetan Buddhism, Lakshmi is an important deity, especially in the Gelug School. She has both peaceful and wrathful forms; the latter form is known as Palden Lhamo, Shri Devi Dudsol Dokam, or Kamadhatvishvari, and is the principal female protector of (Gelug) Tibetan Buddhism and of Lhasa, Tibet.

The Japanese goddess of fortune and prosperity, Kishijoten (吉祥天, 'Auspicious Heavens'), corresponds to Lakshmi.[95] Kishijoten is considered the sister of Bishamon (毘沙門, also known as Tamon or Bishamon-ten), who protects human life, fights evil, and brings good fortune. In ancient and medieval Japan, Kishijoten was the goddess worshiped for luck and prosperity, particularly on behalf of children. Kishijoten was also the guardian goddess of Geishas. While Bishamon and Kishijoten are found in ancient Chinese and Japanese Buddhist literature, their roots have been traced to deities in Hinduism.[95]

Lakshmi is closely linked to Dewi Sri, who is worshipped in Bali as the goddess of fertility and agriculture.

See also

Notes

References

- lakṣmī Archived 20 May 2015 at the Wayback Machine, Monier-Williams' Sanskrit–English Dictionary, University of Washington Archives

- Anand Rao (2004). Soteriologies of India. LIT Verlag Münster. p. 167. ISBN 978-3-8258-7205-2. Archived from the original on 26 December 2018. Retrieved 22 September 2016.

- "Lakshmi". Lexico UK Dictionary. Oxford University Press.

- "Lakshmi". Oxford English Dictionary (Online ed.). Oxford University Press. (Subscription or participating institution membership required.)

- Coulter, Charles Russell; Turner, Patricia (4 July 2013). Encyclopedia of Ancient Deities. ISBN 9781135963903.

- Ph.D, James G. Lochtefeld (15 December 2001). The Illustrated Encyclopedia of Hinduism, Volume 1. The Rosen Publishing Group, Inc. ISBN 978-0-8239-3179-8.

- Mark W. Muesse. The Hindu Traditions: A Concise Introduction. Fortress Press. p. 157. ISBN 978-1451414004.

- Upendra Nath Dhal (1978). Goddess Laksmi: Origin and Development. Oriental Publishers & Distributors. p. 109.

Goddess Lakşmī is stated as the genetrix of the world; she maintains them as a mother ought to do . So she is often called as the Mātā.

- Williams, George M. (2003). Handbook of Hindu Mythology. ABC-CLIO, Inc. p. 196-8. ISBN 1-85109-650-7.

- Sashi Bhusan Dasgupta (2004). Evolution of Mother Worship in India. Advaita Ashrama (A Publication House of Ramakrishna Math, Belur Math). p. 20. ISBN 9788175058866.

- Isaeva 1993, p. 252.

- James G. Lochtefeld (15 December 2001). The Illustrated Encyclopedia of Hinduism, Volume 1. The Rosen Publishing Group. p. 65. ISBN 978-0823931798.

- Laura Amazzone (2012). Goddess Durga and Sacred Female Power. University Press of America. pp. 103–104. ISBN 978-0-7618-5314-5. Archived from the original on 26 December 2018. Retrieved 15 October 2016.

- James G. Lochtefeld (2002). The Illustrated Encyclopedia of Hinduism: A-M. The Rosen Publishing Group. pp. 385–386. ISBN 978-0-8239-3179-8. Retrieved 15 October 2016.

- Heinrich Robert Zimmer (2015). Myths and Symbols in Indian Art and Civilization. Princeton University Press. p. 100. ISBN 978-1-4008-6684-7. Retrieved 15 October 2016.

- Rhodes, Constantina. 2011. Invoking Lakshmi: The Goddess of Wealth in Song and Ceremony. State University of New York Press, ISBN 978-1438433202. pp. 29–47, 220–52.

- "Divali – THE SYMBOLISM OF LAKSHMI." Trinidad and Tobago: National Library and Information System Authority. 2009. Archived from the original on 8 November 2014.

- Singh, Upinder. 2009. A History of Ancient and Early Medieval India: From the Stone Age to the 12th Century. ISBN 978-8131711200, Pearson Education. p. 438

- Vishnu, Asha. 1993. Material life of northern India: Based on an archaeological study, 3rd century B.C. to 1st century BCE. ISBN 978-8170994107. pp. 194–95.

- Roveda, Vitorio. 2004. "The Archaeology of Khmer Images." Aséanie 13(13):11–46.

- Jones, Soumya. 2007. "O goddess where art thou?: Reexamining the Female Divine Presence in Khmer art Archived 9 November 2014 at the Wayback Machine." SEAP Bulletin (Fall):28–31.

- Jones, Constance. 2011. In Religious Celebrations: An Encyclopedia of Holidays, Festivals, Solemn Observances, and Spiritual Commemorations, edited by J. G. Melton. ISBN 978-1598842050, pp. 253–54, 798.

- "lakṣ, लक्ष्." Monier-Williams Sanskrit-English Dictionary. Germany: University of Koeln. Archived 20 May 2015 at the Wayback Machine

- Plum-Ucci, Carol. Celebrate Diwali. ISBN 978-0766027787. pp. 79–86.

- "lakṣaṇa." Monier-Williams Sanskrit-English Dictionary. Germany: University of Koeln. Archived 20 May 2015 at the Wayback Machine.

- Rhodes, Constantina. 2011. Invoking Lakshmi: The Goddess of Wealth in Song and Ceremony. State University of New York Press, ISBN 978-1438433202.

- Vijaya Kumara, 108 Names of Lakshmi, Sterling Publishers, ISBN 9788120720282

- The Toranas are dated to the 1st century CE. See: Ornament in Indian Architecture, Margaret Prosser Allen, University of Delaware Press, 1991, p.18

- "The Calcutta Review". 1855.

- Vanamali (21 July 2008). Shakti: Realm of the Divine Mother. Simon and Schuster. ISBN 978-1-59477-785-1.

- Parasarthy, A. 1983. Symbolism in Hinduism. Chinmaya Mission Publication. ISBN 978-8175971493. pp. 57–59.

- Parasarthy, A. 1983. Symbolism in Hinduism. Chinmaya Mission Publication. ISBN 978-8175971493. pp. 91–92, 160–62.

- Nathan, R. S. 1983. Symbolism in Hinduism. Chinmaya Mission Publication. ISBN 978-8175971493. p. 16.

- Gibson, Lynne. 2002. Hinduism. Heinemann. ISBN 978-0435336196. p. 29.

- Werness, Hope. 2007. Continuum Encyclopedia of Animal Symbolism in World Art. Bloomsbury. ISBN 978-0826419132. pp. 159–67.

- Ajnatanama. 1983. Symbolism in Hinduism. Chinmaya Mission Publication. ISBN 978-8175971493. pp. 317–18.

- Pal 1986, p. 79.

- Journal, Volumes 6-7. Asiatic Society (Kolkata, India). 1964. p. 96.

From the occurrence of cornucopiae, lotus flower and lion mount the goddess has been described as Lakshmi - Ambikā — a composite icon combining the concepts of Śrī or Lakshmi, the goddess of prosperity, and Ambikā, the mother aspect of Durga.

- Jackie Menzies (2006). Goddess: Divine Energy. Art Gallery of New South Wales. p. 113.

- Mihindukalasūrya Ār. Pī. Susantā Pranāndu (2005). Rituals, Folk Beliefs, and Magical Arts of Sri Lanka. Susan International. p. 228. ISBN 9789559631835.

Lion: It was a 'vahana' of Lakshmi, the Goddess of Prosperity, and Parvati, the wife of Siva.

- D. R. Rajeswari (1989). Sakti Iconography. Intellectual Publishing House. p. 22. ISBN 9788170760153.

In some places Gazalakshmi also has been given Lion as her Vahana. In South India Vara Lakshmi, one of the forms of eight Lakshmis is having Lion as her Vahana. In Rameshwaram also for Veera Lakshmi Lion is Vahana. She carries Trisula, Sphere, Sankha, Chakr, and Abhaya and Varada mudras.

- Muir, John, ed. 1870. "Lakshmi and Shri." Pp. 348–49 in Original Sanskrit Texts on the Origin and History of the People of India – Their Religions and Institutions at Google Books, volume 5. London: Trubner & Co.

- "अप क्रामति सूनृता वीर्यं पुन्या लक्ष्मीः"; अथर्ववेद: काण्डं 12 Archived 8 October 2016 at the Wayback Machine Atharva Veda Sanskrit Original Archive

- Naama Drury (2010), The Sacrificial Ritual in the Satapatha Brahmana, ISBN 978-8120826656, pages 61–102

- Williams, Monier. Religious Thought and Life in India, Part 1 (2nd ed.). Archived 16 March 2016 at the Wayback Machine.

- Ramayana, i.45.40–43

- Mahadeva, A. 1950. "Saubhagya-Lakshmi Upanishad." In The Shakta Upanishads with the Commentary of Sri Upanishad Brahma Yogin, Adyar Library Series 10. Madras.

- Saubhagya Lakshmi Upanishad (Original text, in Sanskrit). Archived 8 November 2014 at the Wayback Machine.

- Warrier, A. G. Krishna, trans. 1931. Saubhagya Lakshmi Upanishad. Chennai: Theosophical Publishing House. ISBN 978-0835673181.

- Mahadeva, A. 1950. "Saubhagya-Lakshmi Upanishad." In The Shakta Upanishads with the Commentary of Sri Upanishad Brahma Yogin, Adyar Library Series 10. Madras.

- van Buitenen, J. A. B., trans. Classical Hinduism: A Reader in the Sanskrit Puranas, edited by Cornelia Dimmitt. Temple University Press. ISBN 978-0877221227. pp. 95–99

- Sternbach, Ludwik. 1974. Subhasita, Gnomic and Didactic Literature, A History of Indian Literature 4. Otto Harrassowitz Verlag. ISBN 978-3447015462.

- Kinsley, David. 1988. M1 Hindu Goddesses: Vision of the Divine Feminine in the Hindu Religious Traditions. Berkeley: University of California Press. ISBN 978-0-520-06339-6. pp. 31–32.

- Charles Russell Coulter; Patricia Turner (2013). Encyclopedia of Ancient Deities. Routledge. p. 285. ISBN 978-1-135-96390-3.

- Tracy Pintchman (2001). Seeking Mahadevi: Constructing the Identities of the Hindu Great Goddess. State University of New York Press. pp. 84–85. ISBN 978-0-7914-5007-9.

- Pintchman 2014, p. 82.

- Gupta 2000, p. 27.

- Gupta, Sanjukta (2000). Laksmi Tantra. Motilal Banarsidass Publishe. ISBN 978-81-208-1735-7.

- Sanjukta Gupta (2000). Laksmi Tantra. Motilal Banarsidass Publishe. p. 52.

- Fuller, Christopher John. 2004. The Camphor Flame: Popular Hinduism and Society in India. Princeton University Press. ISBN 978-0691120485. p. 41.

- https://books.google.co.in/books?id=9dNOT9iYxcMC&pg=PA986&dq=lakshmi+daughter+Durga&hl=en&sa=X&ved=2ahUKEwji69y83YHuAhXWDnIKHRdLDF4Q6AEwAnoECAAQAg#v=onepage&q=lakshmi%20daughter%20Durga&f=false

- Edward Balfour (1873). Cyclopædia of India and of Eastern and Southern Asia. Adelphi Press. pp. 10–11. Archived from the original on 26 December 2018. Retrieved 22 September 2016.

- T. N. Srinivasan (1982). A Hand Book of South Indian Images: An Introduction to the Study of Hindu Iconography. Tirumalai-Tirupati Devasthanams. p. 96.

- S. M. Srinivasa Chari (1994). Vaiṣṇavism: Its Philosophy, Theology, and Religious Discipline. Motilal Banarsidass Publishers. p. 176. ISBN 978-8120810983.

- Singh, Upinder (2008). A History of Ancient and Early Medieval India: From the Stone Age to the 12th Century. Pearson Education India. p. 438. ISBN 978-81-317-1677-9. Archived from the original on 13 January 2020. Retrieved 15 December 2019.

- S. M. Srinivasa Chari (1994). Vaiṣṇavism: Its Philosophy, Theology, and Religious Discipline. Motilal Banarsidass Publishers. p. 177. ISBN 978-8120810983.

- Chitta Ranjan Prasad Sinha (2000). Proceedings of the 9th Session of Indian Art History Congress, Hyderabad, November 2000. Indian Art History Congress. p. 61.

Of the four Vedas : Rig, Yajur, Sāma and Atharva, Puruşa Sukta of Rig Veda identifies Lord Vişņu as the Cosmic God . Sri Suktam, Bhu Suktam and Nila Suktam of Rig Veda reveals the glory of Lakşmi and her forms Sri, Bhū and Nila.

- Knapp, Stephen. Spiritual India Handbook. ISBN 978-8184950243. p. 392.

- Rao, A.V.Shankaranarayana (2012). Temples of Tamil Nadu. Vasan Publications. pp. 195–99. ISBN 978-81-8468-112-3.

- Dehejia, Vidya, and Thomas Coburn. Devi: the great goddess: female divinity in South Asian art. Smithsonian. ISBN 978-3791321295.

- Dallapiccola, Anna. 2007. Indian Art in Detail. Harvard University Press. ISBN 978-0674026919. pp. 11–27.

- "Why Lakshmi goes to wrong people?". english.webdunia.com. Archived from the original on 20 December 2019. Retrieved 24 August 2020.

- Om Lata Bahadur 2006, pp. 92–93.

- Kinsley 1988, pp. 33–34.

- Vera, Zak (February 2010). Invisible River: Sir Richard's Last Mission. ISBN 978-1-4389-0020-9. Archived from the original on 26 December 2018. Retrieved 26 October 2011.

First Diwali day called Dhanteras or wealth worship. We perform Laskshmi-Puja in evening when clay diyas lighted to drive away shadows of evil spirits.

- "Diwali." Encyclopædia Britannica. 2009. Archived 14 November 2012 at the Wayback Machine

- Mead, Jean. How and why Do Hindus Celebrate Divali? ISBN 978-0-237-534-127.

- Pramodkumar (March 2008). Meri Khoj Ek Bharat Ki. ISBN 978-1-4357-1240-9. Archived from the original on 4 August 2020. Retrieved 26 October 2011.

It is extremely important to keep the house spotlessly clean and pure on Diwali. Lamps are lit in the evening to welcome the goddess. They are believed to light up her path.

- Solski, Ruth (2008). Big Book of Canadian Celebrations. S&S Learning Materials. ISBN 978-1-55035-849-0. Archived from the original on 4 August 2020. Retrieved 26 October 2011.

Fireworks and firecrackers are set off to chase away evil spirits, so it is a noisy holiday too.

- India Journal: ‘Tis the Season to be Shopping Devita Saraf, The Wall Street Journal (August 2010)

- "Sharad Poornima". Archived from the original on 29 December 2012.

- "Observe Vaibhav Laxmi fast on Friday for prosperity - Times of India". The Times of India. Archived from the original on 29 February 2020. Retrieved 13 December 2019.

- Lakshmi Stotra. Sanskrit documents. Archived 12 September 2016 at the Wayback Machine

- Upinder Singh (2009), A History of Ancient and Early Medieval India: From the Stone Age to the 12th Century, ISBN 978-8131711200, Pearson Education, pages 438, 480 for image

- Duffield Osborne (1914), A Graeco-Indian Engraved Gem Archived 1 February 2016 at the Wayback Machine, American Journal of Archaeology, Vol. 18, No. 1, pages 32–34

- "The Tribune, Chandigarh, India – Jammu & Kashmir". Tribuneindia.com. Archived from the original on 2 November 2012. Retrieved 9 November 2012.

- "Casa della Statuetta Indiana or House of the Indian Statuette". Pompeii in Pictures. Archived from the original on 23 March 2015. Retrieved 10 February 2015.

- Vidya Dehejia (2013). The Body Adorned: Sacred and Profane in Indian Art. Columbia University Press. p. 151. ISBN 978-0-231-51266-4.

The Vishnu-Lakshmi imagery on the Jain temple speaks of the close links between various Indian belief systems and the overall acceptance by each of the values adopted by the other

- Robert S. Ellwood; Gregory D. Alles (2007). The Encyclopedia of World Religions. Infobase Publishing. p. 262. ISBN 978-1-4381-1038-7. Archived from the original on 6 July 2017. Retrieved 15 October 2016.

- Dehejia, Vidya. 2009. The Body Adorned: Sacred and Profane in Indian Art. Columbia University Press. ISBN 978-0231140287. p. 151.

- Jacobi, Hermann. The Golden Book of Jainism, edited by Max Muller, and Mahendra Kulasrestha. ISBN 978-8183820141. p. 213.

- Wangu, Madhu Bazaz (2003). Images of Indian Goddesses: Myths, Meanings, and Models. p. 57. ISBN 9788170174165. Archived from the original on 22 April 2019.

The Goddess Lakshmi in Buddhist Art: The goddess of abundance and good fortune, Lakshmi, reflected the accumulated wealth and financial independence of the Buddhist monasteries. Her image became one of the popular visual themes carved on their monuments.

- Heinrich Robert Zimmer (2015). Myths and Symbols in Indian Art and Civilization. Princeton University Press. p. 92. ISBN 978-1-4008-6684-7. Archived from the original on 6 September 2017. Retrieved 15 October 2016.

- Shaw, Miranda. 2006. "Chapter 13." Pp. 258–62 in Buddhist Goddesses of India. Princeton University Press. ISBN 978-0691127583.

- Charles Russell Coulter; Patricia Turner (2013). Encyclopedia of Ancient Deities. Routledge. pp. 102, 285, 439. ISBN 978-1-135-96390-3. p. 102: "Kishijoten, a goddess of luck who corresponds to Lakshmi, the Indian goddess of fortune..."

Bibliography

- Pal, Pratapaditya (1986), Indian Sculpture: Circa 500 B.C.-A.D. 700, University of California Press, ISBN 978-0520059917

- Isaeva, N. V. (1993), Shankara and Indian Philosophy, SUNY Press, ISBN 978-0791412817

- Gupta, Sanjukta (2000), Laksmi Tantra, Motilal Banarsidass Publishe, ISBN 978-8120817357

Further reading

- Venkatadhvari (1904). Sri Lakshmi Sahasram. Chowkhamba Sanskrit Depot, Benares. (in Sanskrit only)

- Dilip Kododwala, Divali, p. 11, at Google Books, ISBN 978-0237528584

- Kinsley, David (1988). Hindu Goddesses: Visions of the Divine Feminine in the Hindu Religious Tradition. University of California Press. ISBN 978-0-520-90883-3.

- Lakshmi Puja and Thousand Names (ISBN 1-887472-84-3) by Swami Satyananda Saraswati

%252C_Museum_of_Vietnamese_History%252C_Ho_Chi_Minh_City_-_20121014.JPG.webp)