Ambassador Bridge

The Ambassador Bridge is a tolled, international suspension bridge across the Detroit River that connects Detroit, Michigan, United States, with Windsor, Ontario, Canada. It is the busiest international border crossing in North America in terms of trade volume, carrying more than 25% of all merchandise trade between the United States and Canada. A 2004 Border Transportation Partnership study showed that 150,000 jobs in the region and US$13 billion in annual production depend on the Detroit–Windsor international border crossing.[3]

Ambassador Bridge | |

|---|---|

Ambassador Bridge from the Canadian side of the Detroit River | |

| Coordinates | 42.312°N 83.074°W |

| Carries | 4 undivided lanes of |

| Crosses | Detroit River |

| Locale | Detroit–Windsor |

| Official name | Ambassador International Bridge |

| Maintained by | Detroit International Bridge Company and Canadian Transit Company |

| Characteristics | |

| Design | Suspension bridge |

| Total length | 7,500 feet (2,300 m)[1] |

| Longest span | 1,850 feet (560 m)[1] |

| Clearance below | 152 feet (46 m)[1] |

| History | |

| Constructed by | McClintic-Marshall Company |

| Construction start | August 16, 1927[2] |

| Construction end | November 6, 1929[2] |

| Opened | November 15, 1929[2] |

| Statistics | |

| Daily traffic | 10,000+ trucks per day, 4,000+ autos per day |

| Toll | US$5.00 / CA$6.25 |

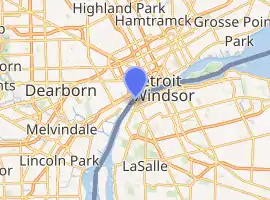

| Location | |

| |

The bridge is one of the few privately owned US–Canada crossings; it was owned by Grosse Pointe billionaire Manuel Moroun, until his death in July 2020, through the Detroit International Bridge Company in the United States[4] and the Canadian Transit Company in Canada.[5] In 1979, when the previous owners put it on the New York Stock Exchange and shares were traded, Moroun was able to buy shares, eventually acquiring the bridge.[6][7] The bridge carries 60 to 70 percent of commercial truck traffic in the region.[8][9] Moroun also owned the Ammex Detroit Duty Free Stores at both the bridge and the tunnel.[10]

History

The passage across the Detroit River became an important traffic route following the American Civil War. The Michigan Central and the Great Western railroads in addition to others operated on either side of the border connecting Chicago with the Atlantic Seaboard. To cross the Detroit River, these railroads operated ferries between docks on either side. The ferries lacked the capacity to handle the shipping needs of the railroads, and there were often 700–1,000 freight cars waiting to cross the river, with numerous passengers delayed in transit. Warehouses in Chicago were forced to store grain that they could not ship to eastern markets and foreign goods were stored in eastern warehouses waiting shipment to the western United States. The net effect of these delays increased commodity prices in the country, and both merchants and farmers wanted a solution from the railroads.[11]

The Michigan Central proposed the construction of a tunnel under the river with the support of their counterparts at the Great Western Railway. Construction started in 1871 and continued until ventilating equipment failed the next year; work was soon abandoned. Attention turned in 1873 to the alternative of building a railroad bridge over the river. The U.S. Army Corps of Engineers commissioned a study of a bridge over the Detroit River. Representatives of the shipping industry on the Great Lakes opposed any bridge with piers in the river as a hazard to navigation. Discussions continued for the remainder of the decade to no avail; a bridge over the Detroit River was not approved. The U.S. Congress requested a new study for a bridge in 1889, but no bridge was approved. Finally, the Michigan Central built the Detroit River Tunnel in 1909–10 to carry trains under the river. This tunnel benefited the Michigan Central and Great Western railroads, but the Canada Southern Railway and other lines still preferred a bridge over the river.[12] Plans for a bridge were revived in 1919 to commemorate the end of World War I and to honor the "youth of Canada and the United States who served in the Great War".[13]

However neither Ontario nor Michigan wanted to finance a river crossing. Michigan automakers subsequently decided to take the initiative to connect the Midwest to central Canada. After they created a bridge company, the project got into trouble when a Toronto financier hired to sell its securities instead embezzled the money and ran off, before ultimately committing suicide in a prison cell after conviction for murdering a drugstore clerk. The bridge boosters turned to New Yorker Joseph A. Bower, a businessman who specialized in rescuing mismanaged companies. Bower succeeded in raising the necessary initial $12 million. "The only way things can be done today, is by private business," said Henry Ford, who backed the project.[14]

The Ambassador Bridge opened November 15, 1929, at a total cost of $23.5 million.[15]

A Canadian immigration inspector jumped to his death in April 1930, shortly after the bridge opened. The bridge has been used by other suicide jumpers. After it opened, high divers considered it as a venue for a record; but after measurements of the height and currents were taken into account, they were dissuaded and abandoned the attempt.[16]

Design

The bridge over the Detroit River had the longest suspended central span in the world when it was completed in 1929—1,850 feet (560 m). This record held until the George Washington Bridge between New York and New Jersey opened in 1931. The bridge's total length is 7,500 feet (2,286 m). Construction began in 1927 and was completed in 1929. The general contractor and steel erector was the McClintic-Marshall Company of Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania.[17]

The bridge is made up of 21,000 short tons (19,000 tonnes) of steel, and the roadway rises as high as 152 feet (46 m) above the Detroit River. Only the main span over the river is supported by suspension cables; the approaches to the main pillars are held up by steel in a cantilever truss structure.[18]

The bridge's only sidewalk is on the structure's southwest side. After the September 11 attacks, pedestrians and bicycles were prohibited from traveling across the bridge due to increased security measures.[19] For years prior to September 11, 2001, the sidewalk was closed due to ongoing maintenance projects and repainting.[20]

Originally painted gloss black, the bridge underwent a five-year refurbishment between 1995 and 2000, which included stripping and repainting the bridge teal.[21]

Granite blocks, originally used on the U.S. side, were given to the Windsor Parks and Recreation Department, and now grace many of the pathways in Windsor parks.[22]

Capacity

The Ambassador Bridge is the busiest crossing on the Canada–United States border.[23] The four-lane bridge carries more than 10,000 commercial vehicles on a typical weekday. The Gateway Project, a major redesign of the U.S. plaza completed in July 2009, provides direct access to Interstate 96 (I-96) and I-75 on the American side and Highway 3 on the Canadian side. The Canadian end of the bridge connects to busy city streets in west Windsor, leading to congestion.[24]

The privately owned bridge carries approximately 25% of trade between Canada and the United States.[25][26]

Additional bridge proposals

.jpg.webp)

The Canadian and United States governments have approved the construction of the Gordie Howe International Bridge proposed by the Detroit River International Crossing (DRIC) commission.[27] The new bridge further downriver between Detroit and Windsor will be owned and operated by the Windsor-Detroit Bridge Authority, a Crown corporation owned by the Canadian federal government.

Manuel "Matty" Moroun, past private owner of the Ambassador Bridge, spoke out against this proposal. He sued the governments of Canada and Michigan to stop its construction, and released a proposal to build a second span of the Ambassador Bridge (which he would own) instead.[28] Critics suggest that Moroun's opposition was fueled by the prospect of lost profits from duty-free gasoline sales, which are exempt from about 60 cents per gallon in taxes even though the pump price to consumers is only a few cents lower.[10] On May 5, 2011, a judge dismissed the case, citing a lack of reasoning for it to proceed.[29] Maroun and his company contended that the new bridge would affect its proposal for a second span which would be built next to the Ambassador Bridge.

Michigan and Canadian authorities continued to support the Gordie Howe International Bridge proposal, since it directly connects the Canadian E.C. Row Expressway and the 2015 extension of Ontario Highway 401 (which runs concurrently as a shared highway for 2 kilometres (1.2 mi) to the future crossing as the Windsor–Essex Parkway) with I-75 and I-96 in Michigan, bypasses Windsor's surface streets and reduces congestion. An agreement announced on June 15, 2012, ensures the new bridge could proceed, with the Canadian federal government funding bridge construction, land acquisition in Michigan and the construction of ramps from I-75. The Canadian contribution will be repaid from bridge tolls,[30] although to date no study has shown toll revenue forecasts.

The company which owns the Ambassador Bridge proposed its own twin span with six lanes to be built across the Detroit River.[31] Cost estimates range from one to two billion U.S. dollars to build a second span. The new span would be a cable-stayed bridge[32] and would accommodate the bulk of the cross-border traffic with the original span being used for overflow traffic.[33] However, a twin span adjacent to the Ambassador Bridge, by itself, does not address Canadian concerns about traffic on Huron Church Road in Windsor. While many of the stop lights commonly cited have been removed by the expansion of the 401 which will connect to the downriver Howe bridge, the final approach to the Ambassador Bridge remains on overcrowded Windsor surface streets.[34][35]

In April 2013, the U.S. State Department issued a Presidential permit to the state of Michigan for a new international crossing between the United States and Canada.[36] Moroun filed a lawsuit attempting to block the issuance of this permit, claiming that the Presidential permit process is unconstitutional.[36]

Controversies

The bridge's private ownership has been controversial as the bridge carries approximately 25% of trade between Canada and the United States.[25] Although alternate routes exist, including the nearby Detroit–Windsor Tunnel, preventing monopoly status, the route is of significant value since it passes directly through major metropolitan areas. It is the shortest possible route from Toronto to many areas in the American Midwest of Michigan, Ohio, Indiana, and Illinois. The aforementioned tunnel prohibits certain vehicles.

In 2010 and 2011, the Wayne County Circuit Court found the Detroit International Bridge Company in contempt for failing to directly connect bridge access roads to I-75 and I-96, and making other required improvements as part of the Gateway Project.[26] These improvements would normally be under the control of the state government; however, the Detroit International Bridge Company withheld the improvements as part of a negotiation strategy. At one point, Matty Moroun and his chief deputy at the Detroit International Bridge Co, Dan Stamper, were jailed for non-compliance with orders to complete the on-ramps.[37]

After years of legal battles, activism by local people against neighborhood truck traffic, and stalling by Matty Moroun, the Michigan Department of Transportation (MDOT) took over the I-75/I-96 on-ramp project and opened the ramps in September 2012 after a six-month construction period.[38] One possible motive for the Gateway Project delays was Moroun's desire to route traffic past his lucrative duty-free store and fuel pumps,[39] one of only two border locations to sell untaxed fuel (the other is International Falls, Minnesota).[10] Critics of the duty-free fuel operation objected that sixty cents from each U.S. gallon went not to paving Michigan's underfunded highways but instead directly to Matty Moroun.[40]

Operators of large trucks under the International Fuel Tax Agreement, which in theory should impose Ontario tax and partially refund Michigan tax on fuel purchased in Detroit and consumed on Ontario's Highway 401, may be disqualified for the Michigan IFTA refund, as the tax was never paid.[41] In a 2012 lawsuit, the Michigan Department of Agriculture and Rural Development sued Moroun's company, Ammex, claiming it mislabeled motorcar fuels to advertise 93 octane while tests showed as little as 91.2 octane.[42]

In recent years the bridge has been criticized for its decaying appearance and crumbling concrete.[43]

See also

- Blue Water Bridge, which links Port Huron, Michigan, to Sarnia, Ontario

- Sault Ste. Marie International Bridge, which links Sault Ste. Marie, Michigan, to Sault Ste. Marie, Ontario

References

- Hatt, WK (1930). Detroit River Bridge. Pittsburgh: McClintic-Marshall Company. p. 4. OCLC 43148098.

- Hatt (1930), p. 7.

- Detroit Regional Chamber (2006). "Detroit–Windsor Border Update: Part I-Detroit River International Crossing Study". Detroit Regional Chamber. Archived from the original on March 21, 2006.

- Guyette, Curt (March 28, 2007). "Over the Border: Legislator Says Proposed Development Authority Would Create Jobs, Boost Economy". Metro Times (Editorial).

- O'Brien, Jennifer (August 3, 2011). "Bridge Brouhaha". The London Free Press. Retrieved December 15, 2011.

- Voyles, S. (May–June 2009). "The Man Behind the Bridge". Corp!. Archived from the original on June 28, 2013.

- "Wikileaks and the DRIC Smoking Guns". Corp!. November 2011. Archived from the original on January 15, 2013. Retrieved August 27, 2012.

- "Traffic Data". Public Border Operators Association. Retrieved August 27, 2012.

- Federal Highway Administration & Michigan Department of Transportation. "Final Environmental Impact Statement and Final Section 4(f) Evaluation". Partnership Border Study. Retrieved August 27, 2012.

- "Tax-Free Fuel Sales Are Bonanza for Ambassador Bridge Owners". Detroit Free Press. April 25, 2011. Retrieved April 25, 2011.

- Mason, Philip P. (1987). The Ambassador Bridge: A Monument to Progress. Detroit: Wayne State University Press. pp. 31+. ISBN 978-0-814-31840-9.

- Mason (1987), pp. 32–47.

- Mason (1987), p. 48.

- Savage, Luiza Ch. (May 21, 2015). "Canada's Battle for a New Cross-Border Bridge". Maclean's. Retrieved June 3, 2020.

- Hanson, Adriane & Dow, Kathleen (2005–2007). "Finding aid for Ambassador Bridge Records, 1927–1930". Special Collections Library. University of Michigan. Retrieved June 3, 2014.

- Mason (1987), p. 130.

- Hyde, Charles K. (1993). Historic Highway Bridges of Michigan. Detroit: Wayne State University Press. p. 148. ISBN 0-8143-2448-7. OCLC 27011079.

- "History of the Ambassador Bridge" (PDF). Detroit International Bridge Company. March 25, 2010.

- "Ambassador Bridge". detroit1701.org.

- Freight Management and Operations. Ambassador Bridge Site Report (Report). Federal Highway Administration.

- Rohan, Barry (October 11, 1997). "Paint Job Spans Nations". Detroit Free Press. Retrieved July 5, 2013.

- "History of the Ambassador Bridge" (PDF). Detroit International Bridge Company. March 25, 2010.

- "Chapter 4: The Watery Boundary". United Divide: A Linear Portrait of the USA/Canada Border. The Center for Land Use Interpretation. Winter 2015.

- Detroit River International Crossing Study team (May 1, 2008). Parkway Map (PDF) (Map). URS Corporation. Archived from the original (PDF) on July 6, 2011. Retrieved February 25, 2010.

- Staff (July 12, 2012). "The Proposed New US-Canada Bridge: Guide to the Controversy". Detroit Free Press.

- Michigan Department of Transportation v. Detroit International Bridge Company, 09-015581-CK (Wayne County Circuit Court 2011).

- "$1B Windsor-Detroit Bridge Deal Struck: A Saga that Former Prime Minister Jean Chrétien Started in 2002 Takes a Major Step Forward". CBC News. June 15, 2012.

- "Ambassador Bridge Boss Sues Canada, US". Ottawa: CBC News. March 26, 2010. Archived from the original on December 16, 2010. Retrieved April 20, 2011.

- Kristy, Dylan (May 5, 2011). "Sierra Club, Bridge Lose Bid To Derail NITC". The Windsor Star. Archived from the original on May 8, 2011. Retrieved May 10, 2011.

- "$1B Windsor–Detroit Bridge Deal Struck". CBC News. June 15, 2012. Retrieved June 15, 2012.

- "Michigan Gives Thumbs Up to Twin Ambassador Span: Report". Today's Trucking. March 16, 2007. Archived from the original on September 27, 2007. Retrieved September 5, 2007.

- Elgaaly, Hala. "Draft Finding of No Significant Impact for Ambassador Bridge Enhancement Project" (PDF). U.S. Coast Guard. Retrieved February 10, 2011.

- "Second Span". Ambassador Bridge. Retrieved February 10, 2011.

- "Don't Be Fooled in Fight Over New Bridge, Michigan Will Benefit Most with New Span to Canada". Lansing State Journal (Editorial). April 5, 2011.

- "A Second Detroit River Crossing: Just Build It". Detroit Free Press (Editorial). April 12, 2011.

- Spangler, Todd (April 12, 2013). "US Grants Permit to Build 2nd Detroit–Canada Bridge". USA Today.

- "Mich. Billionaire, 84, Jailed Over Bridge Dispute". USA Today. Retrieved October 1, 2014.

- Brownell, Claire (September 21, 2012). "Ramps Linking Bridge to Michigan Highways Open to Traffic". The Windsor Star.

- "Billionaire Owner of Ambassador Bridge Jailed". Maclean's. Retrieved October 1, 2014.

- "Report: Ambassador Bridge Owners Reap Profits from Tax-Free Gas Sales". MLive. Booth Newspapers. Associated Press. April 25, 2011. Retrieved October 1, 2014.

- "The Folly of Tax-Free Fuel". Today's Trucking. Archived from the original on August 8, 2014. Retrieved July 31, 2014.

- "Michigan Sues Matty Moroun's Duty-Free Company Over Gas Sales". Southfield, MI: WWJ-TV. Retrieved October 1, 2014.

- Lawrence, Eric (October 15, 2015). "Ambassador Bridge rains concrete chunks down on Windsor". Detroit Free Press. Retrieved November 26, 2018.

Further reading

- Fisher, Dale (2003). Building Michigan: A Tribute to Michigan's Construction Industry. Grass Lake, Michigan: Eyry of the Eagle. ISBN 1-891143-24-7.

- "'Good Will' Bridge to Canada Has Longest Span". Popular Mechanics: 206–208. February 1930.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Ambassador Bridge. |