Ancient Indian architecture

Ancient Indian architecture is the architecture of the Indian subcontinent from the Indian Bronze Age to around 800 CE. By this endpoint Buddhism in India had greatly declined, and Hinduism was predominant, and religious and secular building styles had taken on forms, with great regional variation, which they largely retained until and beyond the great changes brought about by the arrival of first Islam, and then Europeans.

Much early Indian architecture was in wood, which has almost always decayed or burnt, or brick, which has often been taken away for re-use. The large amount of Indian rock-cut architecture, essentially beginning around 250 BCE, is therefore especially important, as much of it clearly adapts forms from contemporary constructed buildings of which no examples remain. There are also a number of important sites where the floor-plan has survived to be excavated, but the upper parts of structures have vanished.

In the Bronze Age the first cities emerged in the Indus Valley Civilization. Archaeology has unearthed urbanization phase from early Harappan in Kalibangan to the late Harappan phase when urbanization declined but was preserved in few pockets. The urbanization in the Gangetic plains began as early as 1200 BC with the emergence of fortified cities and appearance of Northern Black polished ware."[2][lower-alpha 1][4] The Mahajanapada period was characterized by Indian coins and use of stone in the Indian architecture. The Mauryan period is considered as the beginning of the classical period of Indian architecture. Nagara and Dravidian architectural styles developed in the early medieval period with the rise of Hindu revivalism and predominant role of Hindu temple architecture in the Indian Subcontinent.

Bronze age period

Early Harappan phase

Although the urban phase of Harappa has been dated back to 2600 BC, excavation at Kalibangan from the early or proto-Harappan period already shows an urban development with fortification, grid layout of the city and drain system. The settlement consisted of a fortified city mostly made of mud-brick architecture but characterized by an appearance of fired bricks around 3000 BC which was used to line the drains of the city. Planned settlements from an early Harappan era with structures parallel to the streets which run perpendicular to each other with public drainage system has been uncovered at the site of Rakhigarhi, one of the biggest urbanized areas of the Indus valley civilization dating back to 4000 BC-3200 BC. Even earlier phase dated 4400-4200 BC has marked the appearance of wedge shaped mud bricks with rectangular houses.[5]

Building complex of Bhavnagar

Archaeologists discovered a huge building complex dating back to 3600-3300 BC which was probably a storage complex, typical mature harappan brick ratios of 4:2:1 were also noted along with a stone platform and the beginnings of Harrapan silo pit. The complex had rooms with rectangular or squarish plan which were all interconnected by some common wall. [6]

English Bond and building material

While in contemporary Bronze Age cultures outside India sun-dried mud bricks were the dominant building material, the Indus Valley civilization preferred to use fired "terracotta" brick instead. A prominent feature of Harappan architecture was also the first use anywhere in the world of English bond in building with bricks. This type of bonding utilized alternate headers and stretchers which is a stronger method of construction. Clay was usually used as cementing material but where better strength was needed, such as for the drains, lime and gypsum mortar was preferred instead. In architecture such as the Great Bath, bitumen was used for waterproofing. The Use of bitumen has been attested as early as the Mehrgarh period, one of the earliest uses in the world as well. The remarkable vertical alignment of the building indicates the use of a Plumb line. The bricks were produced in a standardized ratio of 4:2:1, found throughout the Indus Valley Civilization.[7]

Larger buildings

Harappan seals show architecture besides horned deities which has been translated as either temples, shrines or houses with an upward curving roof with fish tail endings on four corners. The seals indicate formal places of worship.[8] The excavation at Banawali in present day Haryana has also yielded an Apsidal plan which has been interpreted as a temple.[9]

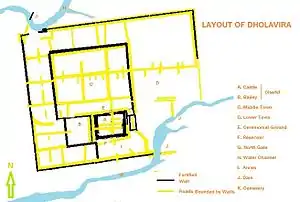

Rectangular stadium-like spaces provided with steps and gateways are known from Dholavira and Juni Kuran.[10] Two stadiums were constructed at Juni Kuran, perhaps one for the commoners and the other for the people with higher status.

At Dholavira, possible funerary architecture was found sorounding a dried up lake and consists of tumuli, sometimes resembling hemispherical domes, constructed using mud bricks or stone slabs. The plan of the base of tumulus is in the shape of a spoked wheel with a chamber in the centre.[11]

Juni Kuran and Mohenjo Daro have pillared halls. In the case of Mohenjodaro L area, the pillars of the hall were constructed using baked bricks and in the case of Juni Kuran, they were made of sandstone pillars with elaborately designed base.[10][12]

Domestic Architecture

The domestic houses were made of bricks and usually flat roofed, the wooden doors were provided with hangings and a lock at the bottom. The houses were single or double storied. The windows were provided with lattice shutters for airflow and privacy and ledge to stop rainwater from entering the house. The houses were usually provided with bathing platform which were connected to the public drain through in house drain. Latrines were generally simple commodes made by burying an old storage pot into the ground. They would have to be cleaned out periodically, but some had a small drain leading outside to a second sump pot. The latrines and bathing platforms were located in a room attached to the outer wall. Kitchen were open air situated in a courtyard as well as closed rooms, hearths oval, circular and rectangular in shape were also used in the house, keyhole ovens with central pillars were used for roasting meat or baking breads.[13]

Late Harappan period

After the collapse of the mature Harappan urban period, some cities still remained urban and inhabited. Sites like Bet Dwarka in Gujarat, Kudwala (38.1 hectares) in Cholistan and Daimabad (20 Ha) in Maharashtra are considered urban. Daimabad (2000-1000 BC) developed a fortification wall with bastions in its Jorwe culture period (1400-1000 BC) and had public buildings such as an elliptical temple, an apsidal temple and shows evidence of planning in the layout of rectangular houses and streets or lanes and planned streets. The area had rose to 50 hectares in with a population of 10,000 people. A 580-meter long protection wall dated 1500 BC was found at Bet Dwarka which is believed to have been damaged and submerged following a sea storm.[14][15] A warehouse dated to 1500 BC at Prahbas Patan (Somnath) from late Harappan period is made of rubble stones set in mud mortar, the artifact includes a stealite seal and storage jars.[16]

Second Urbanization period (1025 BCE – 320 BCE)

Archaeological excavations at Kausambi have revealed fortifications from the end of second millennium BC.[17][18]

A stone palace predating the Mauryan period has been discovered from the ruins of Kausambi. The dressed stones of the palace were set in fine lime and coated with a thick layer of plaster, the entire architecture resembled a fortress with its own walls and towers. The palace had few rooms, each room was provided with three shelves and a central hall with steps leading to the tower. The architecture was constructed in three phases and is dated from 8th century BC to 2nd century BC. Discovery of this stone palace discredits the theory of foreign influence behind the rise of Indian stone architecture during Ashokan or mauryan period.

A technique of architecture applied here was using dressed stones as facing for a wall made of rubble core, this represents the apogee of Indian architecture in this ancient period.[19][20][21]

- Kausambi palace architecture technique applied in later periods

Unfinished Alai Minar's rubble core; the unfinished tower lacks sandstone facing.

Unfinished Alai Minar's rubble core; the unfinished tower lacks sandstone facing. Stone facing of Qutub Minar on its rubble core

Stone facing of Qutub Minar on its rubble core

Ghositarama monastery

Ghoshitaram monastery in Kosambi dating back to 6th-century BCE. Buddhist scripture attributes this very old monastic site to the time of the Buddha which has been backed by archaeology, founded by a banker named Ghosita. The site has been located near Kosambi and identified by inscriptions. Archaeology suggests continuous occupation down to the sixth century when it was likely destroyed in the Hun invasion. Xuanzang found it an unoccupied ruin.[22]

Mahajanapadas

From the time of the Mahajanapadas (600 BCE–320 BCE), walled and moated cities with large gates and multi-storied buildings which consistently used arched windows and doors and made intense use of wooden architecture, are important features of the architecture during this period.[23] The reliefs of Sanchi, dated to the 1st centuries BCE–CE, show cities such as Kushinagar or Rajagriha as splendid walled cities during the time of the Buddha (6th century BCE), as in the Royal cortege leaving Rajagriha or War over the Buddha's relics. These views of ancient Indian cities have been relied on for the understanding of ancient Indian urban architecture. Archaeologically, this period corresponds in part to the Northern Black Polished Ware culture.[24] Geopolitically, the Achaemenid Empire started to occupy the northwestern part of the subcontinent from c, 518 BCE.[25][26]

.jpg.webp) Rajgir, old city walls 6th century BCE

Rajgir, old city walls 6th century BCE

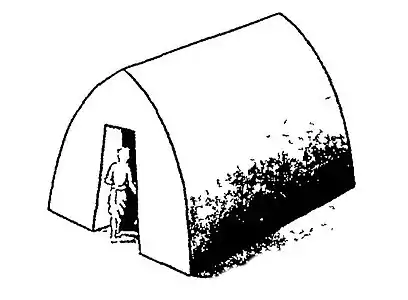

Various types of individual housing of the time of the Buddha (c. 563/480 or c. 483/400 BCE), resembling huts with chaitya-decorated doors, are also described in the reliefs of Sanchi. Particularly, the Jetavana at Sravasti, shows the three favourite residences of the Buddha: the Gandhakuti, the Kosambakuti, and the Karorikuti, with the throne of the Buddha in the front of each. The Jetavana garden was presented to the Buddha by the rich banker Anathapindika, who purchased it for as many gold pieces as would cover the surface of the ground. Hence, the foreground of the relief is shown covered with ancient Indian coins (karshapanas), just as it is in the similar relief at Bharhut.[27] Although the reliefs of Sanchi are dated to the 1st centuries BCE–CE, portraying scene taking place during the time of the Buddha, four centuries before, they are considered an important indication of building traditions in these early times.[28]

Pataliputra Voussoir Arch

A granite stone fragment of an arch, known as Pataliputra Voussoir Arch, discovered by K. P. Jayaswal from Kumhrar, Pataliputra has been analysed as a pre Mauryan Nanda period keystone fragment of a trefoil arch of gateway with mason's marks of three archaic Brahmi letters inscribed on it which probably decorated a Torana.[29][30][31] The wedge shaped stone with indentation has mauryan polish on two sides and was suspended vertically.

Religious architecture

Buddhist caves

During the time of the Buddha (c. 563/480 or c. 483/400 BCE), Buddhist monks were also in the habit of using natural caves, such as the Saptaparni Cave, southwest from Rajgir, Bihar.[32][33] Many believe it to be the site in which Buddha spent some time before his death,[34] and where the first Buddhist council was held after the Buddha died (paranirvana).[32][35][36] The Buddha himself had also used the Indrasala Cave for meditation, starting a tradition of using caves, natural or man-made, as religious retreats, that would last for over a millennium.[37]

Monasteries

The first monasteries, such as the Jivakarama vihara and Ghositarama monastery in Rajgir and Kausambi respectively, were built from the time of the Buddha, in the 6th or 5th centuries BCE.[38][39][40] The initial Jivakarama monastery was formed of two long parallel and oblong halls, large dormitories where the monks could eat and sleep, in conformity with the original regulations of the samgha, without any private cells.[38] Other halls were then constructed, mostly long, oblong building as well, which remind of the construction of several of the Barabar caves.[38][41] The Buddha is said to have been treated once in the monastery, after having been injured by Devadatta.[38][42]

Stupas

Religious buildings in the form of the Buddhist stupa, a dome-shaped monument, started to be used in India as commemorative monuments associated with storing sacred relics of the Buddha.[43] The relics of the Buddha were spread between eight stupas, in Rajagriha, Vaishali, Kapilavastu, Allakappa, Ramagrama, Pava, Kushinagar, and Vethapida.[44] The Piprahwa stupa also seems to have been one of the first to be built.[44] Guard rails—consisting of posts, crossbars, and a coping—became a feature of safety surrounding a stupa.[23] The Buddha had left instructions about how to pay hommage to the stupas: "And whoever lays wreaths or puts sweet perfumes and colours there with a devout heart, will reap benefits for a long time".[45] This practice would lead to the decoration of the stupas with stone sculptures of flower garlands in the Classical period.[45]

Temples

Saurashtra Janapada coins from the stratigraphic phase I dated 600-300 BC provide evidence of elaborate Apsidal Chaitya temples along with domed temples (or stupa), square, cruciform and octagonal temple plans, these coins also provide one of the first representations of Hindu pantheon for instance Gaja Lakshmi etc.[46][47] Elliptical Hindu temples with mandapa from Nagari, Chittorgarh and Vidisha near Heliodorus pillar have been dated to 4th century BC or 350-300 BC.[48][49]

Classical period (320 BCE – 550 CE)

Monumental stone architecture

The next wave of building, appears with the start of the Classical period (320 BCE–550 CE) and the rise of the Mauryan Empire. The capital city of Pataliputra was an urban marvel described by the Greek ambassador Megasthenes. Remains of monumental stone architecture can be seen through numerous artifacts recovered from Pataliputra, such as the Pataliputra capital. This cross-fertilization between different art streams converging on the subcontinent produced new forms that, while retaining the essence of the past, succeeded in integrating selected elements of the new influences.

The Indian emperor Ashoka (rule: 273–232 BCE) established the Pillars of Ashoka throughout his realm, generally next to Buddhist stupas. According to Buddhist tradition, Ashoka recovered the relics of the Buddha from the earlier stupas (except from the Ramagrama stupa), and erected 84.000 stupas to distribute the relics across India. In effect, many stupas are thought to date originally from the time of Ashoka, such as Sanchi or Kesariya, where he also erected pillars with his inscriptions, and possibly Bharhut, Amaravati or Dharmarajika in Gandhara.[44]

Ashoka also built the initial Mahabodhi Temple in Bodh Gaya around the Bodhi tree, including masterpieces such as the Diamond throne ("Vajrasana"). He is also said to have established a chain of hospitals throughout the Mauryan empire by 230 BCE.[50] One of the edicts of Ashoka reads: "Everywhere King Piyadasi (Ashoka) erected two kinds of hospitals, hospitals for people and hospitals for animals. Where there were no healing herbs for people and animals, he ordered that they be bought and planted."[51] Indian art and culture has absorbed extraneous impacts by varying degrees and is much richer for this exposure.

Fortified cities with stūpas, viharas, and temples were constructed during the Maurya empire (c. 321–185 BCE).[23] Architectural creations of the Mauryan period, such as the city of Pataliputra, the Pillars of Ashoka, are outstanding in their achievements, and often compare favourably with the rest of the world at that time. Commenting on Mauryan sculpture, John Marshall once wrote about the "extraordinary precision and accuracy which characterizes all Mauryan works, and which has never, we venture to say, been surpassed even by the finest workmanship on Athenian buildings".[52][53]

Mauryan polished stone pillar from Pataliputra

Mauryan polished stone pillar from Pataliputra Lion Capital of Ashoka from Sarnath, 250 BCE.

Lion Capital of Ashoka from Sarnath, 250 BCE. Cruciform star shaped stupa Lauriya Nandangarh – 4th-3rd century BC stage 1 cruciform, 1 BC stage 3 colossal stupa[54]

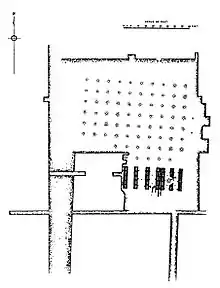

Cruciform star shaped stupa Lauriya Nandangarh – 4th-3rd century BC stage 1 cruciform, 1 BC stage 3 colossal stupa[54] Plan of the 80-columns pillared hall

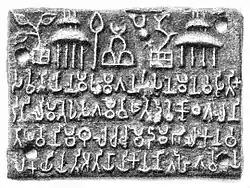

Plan of the 80-columns pillared hall Temple depicted on Soghaura copper plate 3rd century BCE

Temple depicted on Soghaura copper plate 3rd century BCE

Rock-cut caves

Around the same time rock-cut architecture began to develop, starting with the already highly sophisticated and state-sponsored Barabar caves in Bihar, personally dedicated by Ashoka c. 250 BCE.[23] These artificial caves exhibit an amazing level of technical proficiency, the extremely hard granite rock being cut in geometrical fashion and polished to a mirror-like finish.[37]

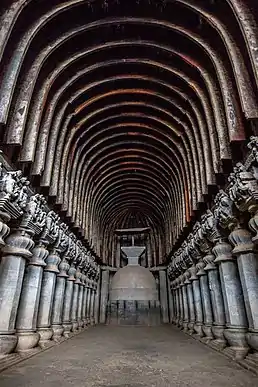

Probably owing to the 2nd century BCE fall of the Mauryan Empire and the subsequent persecutions of Buddhism under Pushyamitra Sunga, it is thought that many Buddhists relocated to the Deccan under the protection of the Andhra dynasty, thus shifting the cave-building effort to western India: an enormous effort at creating religious caves (usually Buddhist or Jain) continued there until the 2nd century CE, culminating with the Karla Caves or the Pandavleni Caves.[37] These caves generally followed an apsidal plan with a stupa in the back for the chaityas, and a rectangular plan with surrounding cells for the viharas.[37] As well as royal patronage, numerous donors provided the funds for the building of these caves and left donation inscriptions, including laity, members of the clergy, government officials, and even foreigners.[56]

The construction of caves would wane after the 2nd century CE, possibly due to the rise of Mahayana Buddhism and the associated intense architectural and artistic production in Gandhara and Amaravati.[37] The building of rock-cut caves would revive briefly in the 5th century CE, with the magnificent achievements of Ajanta[57] and Ellora, before finally subsiding as Hinduism replaced Buddhism in the sub-continent, and stand-alone temples became more prevalent.[23][37]

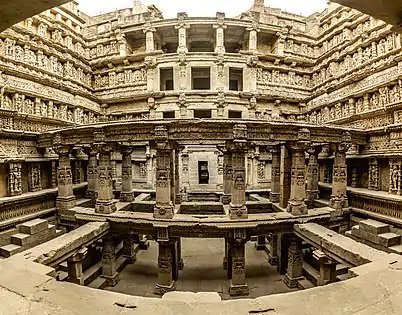

Rock-cut architecture also developed with the apparition of stepwells in India, dating from 200–400 CE.[58] Subsequently, the construction of wells at Dhank (550–625 CE) and stepped ponds at Bhinmal (850–950 CE) took place.[58]

Jain cave monastery in Udayagiri and Khandagiri Caves (2nd century BCE).

Jain cave monastery in Udayagiri and Khandagiri Caves (2nd century BCE). Chitharal Jain Monuments, 1st century BCE

Chitharal Jain Monuments, 1st century BCE.jpg.webp) Gautamiputra vihara at Pandavleni Caves, built in the 2nd century CE by the Satavahana dynasty

Gautamiputra vihara at Pandavleni Caves, built in the 2nd century CE by the Satavahana dynasty The Ajanta Caves are 30 rock-cut Buddhist cave monument built under the Vakatakas, c. 5th century CE.

The Ajanta Caves are 30 rock-cut Buddhist cave monument built under the Vakatakas, c. 5th century CE.

Decorated stupas

Stupas were soon to be richly decorated with sculptural reliefs, following the first attempts at Sanchi Stupa No.2 (125 BCE). Full-fledged sculptural decorations and scenes of the life of the Buddha would soon follow at Bharhut (115 BCE), Bodh Gaya (60 BCE), Mathura (125–60 BCE), again at Sanchi[59] for the elevation of the toranas (1st century BCE/CE) and then Amaravati (1st–2nd century CE).[60] The decorative embellishment of stupas also had a considerable development in the northwest in the area of Gandhara, with decorated stupas such as the Butkara Stupa ("monumentalized" with Hellenistic decorative elements from the 2nd century BCE)[61] or the Loriyan Tangai stupas (2nd century CE). Stupa architecture was adopted in Southeast and East Asia, where it became prominent as a Buddhist monument used for enshrining sacred relics.[43] The Indian gateway arches, the torana, reached East Asia with the spread of Buddhism.[62] Some scholars hold that torii derives from the torana gates at the Buddhist historic site of Sanchi (3rd century BCE – 11th century CE).[63]

Sanchi Stupa No.2, the earliest known stupa with important displays of decorative reliefs, c. 125 BCE[64]

Sanchi Stupa No.2, the earliest known stupa with important displays of decorative reliefs, c. 125 BCE[64]

Slab of Amaravati Marbles, depicting of the Great Amaravati Stupa, with a Buddha statue at the entrance, Amaravathi, Andhra Pradesh, India

Slab of Amaravati Marbles, depicting of the Great Amaravati Stupa, with a Buddha statue at the entrance, Amaravathi, Andhra Pradesh, India Geometrical decorations, Dhamekh Stupa, 500 CE

Geometrical decorations, Dhamekh Stupa, 500 CE

Stand-alone temples

Temples—built on elliptical, circular, quadrilateral, or apsidal plans—were initially constructed using brick and timber.[23] Some temples of timber with wattle-and-daub may have preceded them, but none remain to this day.[66]

Circular dome temples

Some of the earliest free-standing temples may have been of a circular type, as the Bairat Temple in Bairat, Rajasthan, formed of a central stupa surrounded by a circular colonnade and an enclosing wall.[66] It was built during the time of Ashoka, and near it were found two of Ashoka's Minor Rock Edicts.[66] Ashoka also built the Mahabodhi Temple in Bodh Gaya c. 250 BCE, also a circular structure, in order to protect the Bodhi tree under which the Buddha had found enlightenment. Representations of this early temple structure are found on a 100 BCE relief sculpted on the railing of the stupa at Bhārhut, as well as in Sanchi.[67] From that period the Diamond throne remains, an almost intact slab of sandstone decorated with reliefs, which Ashoka had established at the foot of the Bodhi tree.[68][69] These circular-type temples were also found in later rock-hewn caves such as Tulja Caves or Guntupalli.[66]

Remains of the circular Bairat Temple, c. 250 BCE. A stupa was located in the center.

Remains of the circular Bairat Temple, c. 250 BCE. A stupa was located in the center. Relief of a circular temple, Bharhut, c. 100 BCE

Relief of a circular temple, Bharhut, c. 100 BCE Hindu temple dedicated to Shiva depicted in a coin from the 1st century BCE

Hindu temple dedicated to Shiva depicted in a coin from the 1st century BCE

Karttikeya Shrine with antelope in a coin of Yaudheya, Punjab region, 2nd century CE

Karttikeya Shrine with antelope in a coin of Yaudheya, Punjab region, 2nd century CE A dome temple from Satavahana relief 1st-2nd century CE

A dome temple from Satavahana relief 1st-2nd century CE A dome temple from Sannati Stupa relief, 1st-2nd century CE

A dome temple from Sannati Stupa relief, 1st-2nd century CE Amaravathi's Dome temple relief 1st-2nd century CE

Amaravathi's Dome temple relief 1st-2nd century CE

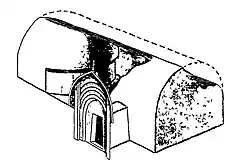

Apsidal temples

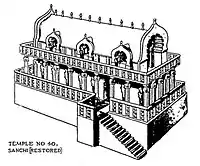

Another early free-standing temple in India, this time apsidal in shape, appears to be Temple 40 at Sanchi, which is also dated to the 3rd century BCE.[72] It was an apsidal temple built of timber on top of a high rectangular stone platform, 26.52x14x3.35 metres, with two flights of stairs to the east and the west. The temple was burnt down sometime in the 2nd century BCE.[73][74] This type of apsidal structure was also adopted for most of the cave temple (Chaitya-grihas), as in the 3rd century BCE Barabar Caves and most caves thereafter, with side, and then frontal, entrances.[66] A freestanding apsidal temple remains to this day, although in a modified form, in the Trivikrama Temple in Ter, Maharashtra.[75]

Trivikrama Temple at Ter: an early Buddhist apsidal temple, in front of which was later added an Hindu square mandapa

Trivikrama Temple at Ter: an early Buddhist apsidal temple, in front of which was later added an Hindu square mandapa Chejarla apsidal temple, also later converted to Hinduism

Chejarla apsidal temple, also later converted to Hinduism

Truncated pyramidal temples

The Mahabodhi Temple in Bodh Gaya is one of the earliest examples of Truncated Pyramidal temples with niches containing Buddha images.[76] The structure is crowned by the shape of an hemispherical stupa topped by finials, forming a logical elongation of the temple.[76]

Although the current structure of the Mahabdhodi Temple dates to the Gupta period (5th century CE), the "Plaque of Mahabodhi Temple", discovered in Kumrahar and dated to 150–200 CE based on its dated Kharoshthi inscriptions and combined finds of Huvishka coins, suggests that the pyramidal structure already existed in the 2nd century CE.[76] This is confirmed by archaeological excavations in Bodh Gaya.[76]

This truncated pyramid design also marked the evolution from the aniconic stupa dedicated to the cult of relics, to the iconic temple with multiple images of the Buddha and Bodhisattvas.[76] This design was very influential in the development of later Hindu temples.[77]

Square prostyle temples

The Gupta Empire later also built Buddhist stand-alone temples (following the great cave temples of Indian rock-cut architecture), such as Temple 17 at Sanchi, dating to the early Gupta period (5th century CE). It consists of a flat roofed square sanctum with a portico and four pillars. From an architectural perspective, this is a tetrastyle prostyle temple of Classical appearance .[78] The interior and three sides of the exterior are plain and undecorated but the front and the pillars are elegantly carved,[78] not unlike the 2nd century rock-cut cave temples of the Nasik Caves. Nalanda and Valabhi universities, housing thousands of teachers and students, flourished between the 4th–8th centuries.[79]

Palatial architecture

Archaeological excavation conducted by Archaeological Survey of India (ASI) at Kausambi revealed a palace with its foundations going back to 8th century BCE until 2nd century CE; and built-in six phases. The last phase dated to 1st - 2nd century CE, featured an extensive structure which was divided into three blocks and enclosed two galleries. There was a central hall in the central block and presumably used as an audience hall surrounded by rooms which served as a residential place for the ruler. The entire structure was constructed using bricks and stones and two layers of lime were plastered on it. The palace had a vast network of underground chambers also called Suranga by Kautilya in his Arthashastra,[80] and the superstructure and the galleries were made on the principle of true arch. The four-centered pointed arch was used to span narrow passageways and segmental arch for wider areas. The superstructure of the central and eastern block was examined to have formed part of a dome that adorned the building. The entire galleries and superstructure were found collapsed under 5 cm thick layer of ash which indicates destruction of the palace through conflagration.[81]

A palace architecture has also been uncovered at Nagarjunakonda.[82]

Shikhara

The early evidence of Shikhara type domical crowing structure has been noted in the palatial architecture of Kausambi dated to 1st-2nd century CE. The central hall was thought to be topped by a dome but analysis of the bricks indicate Shikara type structure was used instead. Evidence also indicates Shikhara was also used in crowing architecture such as Bhitargaon temple.[83]

Theater and stadium

Satavahanas constructed a stadium and a theater at Nagarjunakonda in the 2nd century AD. The theater has a small quadrangular open area enclosed on all four sides by stepped stands which are made of bricks and cladded with limestone.[84][85]

An oblong-shaped stadium dating form the same era consisted of an arena which was enclosed on all four sides by flight of steps with each step measuring two feet wide and a pavilion which was situated on the west end. At the top of the arena there was an eleven feet wide platform. The area of arena was 309 X 259 feet and 15 feet deep. The entire construction was done using burnt brick.

Fortification

Nalrajar Garh fortification wall ruins dating back to 5th-century CE. are probably the only standing fortification ruins from Gupta period which are located in a dense jungle in North Bengal near Indo-Bhutan border. A prominent feature of its fortification walls are two parabolic arches.[86] Many fortified cities like Nalrajar Garh, Bhitagarh had risen in Northeastern India owing to trade activities with southeastern China.

Badami or Pulakeshi fort from Chalukya era date back to the 6th century CE.[87]

End of the Classical period

This period ends with the destructive invasions of the Alchon Huns in the 6th century CE. During the rule of the Hunnic king Mihirakula, over a thousand Buddhist monasteries throughout Gandhara are said to have been destroyed.[88] The Chinese pilgrim Xuanzang, writing in 630 CE, explained that Mihirakula ordered the destruction of Buddhism and the expulsion of monks.[89] He reported that Buddhism had drastically declined, and that most of the monasteries were deserted and left in ruins.[90]

Although only spanning a few decades, the invasions had long-term effects on India, and in a sense brought an end to Classical India.[91] Soon after the invasions, the Gupta Empire, already weakened by these invasions and the rise of local rulers, ended as well.[92] Following the invasions, northern India was left in disarray, with numerous smaller Indian powers emerging after the crumbling of the Guptas.[93]

Early Middle Ages (550 CE–1200 CE)

-1.jpg.webp)

Hindu temple architecture in the Indian subcontinent continued to develop in North India and South India. Nagara style developed in North India where a Hindu temple incorporated Shikhara as its predominant architectural element whereas in southern India Vimana was used instead. The Hindu temple architecture was characterized by the use of stone as the dominant building material compared to the earlier period in which the burnt bricks were used instead.

Regional styles include Architecture of Karnataka, Kalinga architecture, Dravidian architecture, Western Chalukya architecture, and Badami Chalukya Architecture.

The Kandariya Mahadeva Temple at the Khajuraho Temple Complex in the shikhara style architecture, a UNESCO World Heritage Site

The Kandariya Mahadeva Temple at the Khajuraho Temple Complex in the shikhara style architecture, a UNESCO World Heritage Site.jpg.webp)

.jpg.webp) Martand Sun Temple Central shrine, dedicated to the deity Surya

Martand Sun Temple Central shrine, dedicated to the deity Surya

The granite tower of Brihadeeswarar Temple in Thanjavur was completed in 1010 CE by Raja Raja Chola I.[97]

The granite tower of Brihadeeswarar Temple in Thanjavur was completed in 1010 CE by Raja Raja Chola I.[97]

Wall of Jain Temple complex at Deogarh

Wall of Jain Temple complex at Deogarh Devagiri fort, built by Yadava dynasty in the 12th century; according to Ibn Batutta, it was the most impregnable fort he had ever seen.

Devagiri fort, built by Yadava dynasty in the 12th century; according to Ibn Batutta, it was the most impregnable fort he had ever seen..jpg.webp) Jaisalmer Chhatri, 12th century CE

Jaisalmer Chhatri, 12th century CE.jpg.webp) Hira Gate at Dabhoi Fort, 12th century CE

Hira Gate at Dabhoi Fort, 12th century CE

Ancient Indian arches

Indian architecture has utilized mix of false and true arches in its architecture.

Corbel arches

Corbel arches in India date from Indus Valley Civilisation which used corbel arch to construct drains and have been evidenced at Mohenjo daro, Harappa, and Dholavira.[98]

The oldest arches surviving in Indian architecture are the gavaksha or "chaitya arches" found in ancient rock-cut architecture, and agreed to be copied from versions in wood which have all perished. These often terminate a whole ceiling with a semi-circular top; wooden roofs made in this way can be seen in carved depictions of cities and palaces. A number of small early constructed temples have such roofs, using corbelled construction, as well as an apsidal plan; the Trivikrama Temple at Ter, Maharashtra is an example. The arch shape survived into constructed Indian architecture, not as an opening in a wall but as a blind niche projection from a wall, that bears only its own weight. In this form, it became a very common and important decorative motif on Hindu temples.[99]

The "fundamental architectural principle of the constructed Hindu temple is always formulated in the trabeate order", that is to say using post and lintel systems with vertical and horizontal members.[100] According to George Michell: "Never was the principle of the arch with radiating components, such as voussoirs and keystones, employed in Hindu structures, either in India or in other parts of Asia. It was not so much that Hindu architects were ignorant of these techniques, but rather that conformance to tradition and adherence to precedents were firm cultural attitudes".[101] Harle describes the true arch as "not unknown, but almost never employed by Hindu builders",[102] and its use as "rare, but widely dispersed".[103]

Arch

The 19th-century archaeologist Alexander Cunningham, head of the Archaeological Survey of India, at first believed that due to the total absence of arches in Hindu temples, they were alien to Indian architecture, but several pre-Islamic examples bear testimony to their existence, as explained by him in the following manner:[104]

Formerly it was the settled belief of all European enquirers that the ancient Hindus were ignorant of the Arch. This belief no doubt arose from the total absence of arches in any of the Hindu Temples. Thirty years ago I shared this belief with Mr. Fergusson, when I argued that the presence of arches in the great Buddhist Temple at Buddha Gaya proved that the building could not have been erected before the Muhammadan conquest. But during my late employment in the Archeological Survey of India several buildings of undoubted antiquity were discovered in which both vaults and arches formed part of the original construction.

— Alexander Cunningham, Mahâbodhi, or the great Buddhist temple under the Bodhi tree at Buddha-Gaya, 1892

Archaeological evidences indicate that wedge shaped bricks and construction of wells in the Indus valley civilization and although no true arches have been discovered as of yet, these bricks would have been suitable in the construction of true arches.[105] The earliest arch appeared in South Asia as a barrel vault in the Late Harappan Cemetery H culture dated 1900 BC-1300 BC which formed the roof of the metal working furnance, the discovery was made by Vats in 1940 during excavation at Harappa.[106][107][108] True arch in India dates from pre Mauryan Nanda period from 5th century BC. Arch fragment discovered by archaeologist K. P. Jayaswal from an arch with Brahmi inscribed on it,[109][110] or 1st - 2nd century CE when it first appeared in Kausambi palace architecture from Kushana period.[111] Arches present at Vishnu temples at Deo Baranark, Amb and Kafir Kot temples from Hindu Shahi period and Hindu temple of Bhitargaon bear testimony to the use arches in the Hindu temple architecture.[112][113][114] Although Alexander Cunningham has persisted in the notion that the Buddhist Mahabodhi Temple's pointed arch was added later during a Burmese restoration, given its predominant use in Islamic architecture, scholars such as Huu Phuoc Le have contested this assumption based on analysis that relieving arches could not have been added without destroying the entire temple structure, which is dated to 6th-7th century CE. Hence the pointed and relieving arches much have formed part of the original building dating from the pre-Islamic periods in proper.[115][116] Moreover, pointed arches vaulted entrances have been noted in Bhitargaon temple and Kausambi Palace architecture as well.[117][118]

- Variety of Arches in Pre Islamic periods

Parabolic arch, Mahabodhi temple, 1st-2nd century CE

Parabolic arch, Mahabodhi temple, 1st-2nd century CE Pointed arch Mahabodhi temple, 6th-7th century CE, Late-Gupta period

Pointed arch Mahabodhi temple, 6th-7th century CE, Late-Gupta period Semicircular arch, Bhitargaon temple, 4th-5th century CE (heavily reconstructed)

Semicircular arch, Bhitargaon temple, 4th-5th century CE (heavily reconstructed) Cinquefoil arches at Amb, 7th-9th century CE, Hindu Shahis

Cinquefoil arches at Amb, 7th-9th century CE, Hindu Shahis.jpg.webp) Teli ka Mandir gate with particular Rajput style arch, 8th century CE

Teli ka Mandir gate with particular Rajput style arch, 8th century CE Teli ka Mandir gate with multifoil arch, 8th century CE

Teli ka Mandir gate with multifoil arch, 8th century CE

Fortification

Evidence indicates that the construction of fortification walls at Dehli applied nearly the same principle at Red Fort and Agra Fort as was the tradition during pre-Islamic Rajput periods. Excavation of Lal Kot beneath the Purana Qila revealed ruins which was constructed using similar method as in the post-Islamic and Mughal Periods.

- Fortification of pre-Islamic Lal Kot and Agra Fort of Mughal era

Agra Fort used the same technique for fortification walls.

Agra Fort used the same technique for fortification walls.

Notes

- Most sites of the Painted Grey Ware culture in the Ghaggar-Hakra and Upper Ganges Plain were small farming villages. However, "several dozen" PGW sites eventually emerged as relatively large settlements that can be characterized as towns, the largest of which were fortified by ditches or moats and embankments made of piled earth with wooden palisades, albeit smaller and simpler than the elaborately fortified large cities which grew after 600 BCE in the more fully urban Northern Black Polished Ware culture.[3]

References

- "Ellora Caves". UNESCO World Heritage Centre. Retrieved 28 February 2019.

- "Indus Collapse: The End or the Beginning of an Asian Culture?". Science Magazine. 320: 1282–1283. 6 June 2008.

- James Heitzman, The City in South Asia (Routledge, 2008), pp. 12–13

- Shaffer, Jim (1993). "Reurbanization: The eastern Punjab and beyond". In Spodek, Howard; Srinivasan, Doris M. (eds.). Urban Form and Meaning in South Asia: The Shaping of Cities from Prehistoric to Precolonial Times.

- Nath, Amarendra. Excavation at Rakhigarhi [1997-98], [1999-2000]. Archaeological survey of India. p. 129.

- Indian Archaeology: a review 1993-1994 (PDF). Archaeological Survey of India. 1994. pp. 35–38.

- Pruthi, Raj (2004). Prehistory and Harappan Civilization. APH Publishing. ISBN 9788176485814.

- Kenoyer, J.M (2010). The Master of Animals in Old World Iconography. BUDAPEST. p. 50. ISBN 978-963-9911-14-7.

- Danino, Michel (2010). The Lost River: On the Trail of the Sarasvatī. Penguin Books India. ISBN 978-0-14-306864-8.

- Pramanik, Shubhra (2003). "Excavation at Juni Kuran 2003-2004". Puratattva. 34: 45–57.

- Rawat, Yadubirsingh. "Coastal Sites: Possible Port Towns Of Harappan time in Gujarat". Port Towns of Gujarat.

- Green, Adam S (6 September 2017). "Mohenjo-daro's Small Public Structures: Heterarchy, Collective Action, and a Revisitation of Old interpretations with GIS and 3D Modelling" (PDF). Cambridge Archaeological Journal.

- "7 Kenoyer 2015 Indus Civilization.pdf: ANTHRO100: General Anthropology (002)". canvas.wisc.edu. Retrieved 22 August 2020.

- U. Singh (2008), pp. 181, 223

- Basant, P. K. (2012). The City and the Country in Early India: A Study of Malwa. Primus Books. p. 94. ISBN 9789380607153.

daimabad elliptical temple.

- Dhavalikar, M. K. (2011). Ancient India. Archaeological survey of India. pp. 328–330.

- Schlingloff, Dieter (2014). Fortified Cities of Ancient India: A Comparative Study. Anthem Press. pp. 67 According to GR Sharma's monograph, rampart was built and provided with brick revetment between 1025 and 955 BC. ISBN 978-1783083497.

- Sharma, G. R. Indian archaeology a review: 1957-58. Archaeological survey of India. pp. 47-48 In the Earliest Period, I, the defenses consisted of a mud wall with a burnt brick revetment on the exterior, the latter being available to a height of 42 ft. 5 in. and comprising one hundred and fifty-four courses of bricks (pl. LX). The first thirty courses from the bottom showed a batter of about 15 deg from the vertical and the upper courses 40 deg, the bricks being laid throughout in the English bond. Up to the first thirty courses, the revetment was also covered by a 2- to 1/2-in. thick mud plaster. At a height of about 6 ft. from the bottom, there were a number of holes, perhaps weep-holes, situated 6 ft. apart from each other. On the bases of the associated pottery, coins and terracottas the beginnings of the different periods of the defenses maybe dated as follows, Period I, 700 B.C, Period II, 500 B.C, Period III, 300 B.C, Period IV, 50 B.C, and Period V, A. D. 150.

- A., Ghosh (1961). Indian Archaeology: A Review 1960-61. New Dehli: Archaeological Survey of India. pp. 33–35.

- Bates, Crispin; Mio, Minoru (22 May 2015). Cities in South Asia. Routledge. ISBN 9781317565130.

- A., Ghosh (1964). Indian Archaeology: A Review 1961-62. New Dehli: Archaeological Survey of India. pp. 50–52.

- Goldberg, Kory; Decary, Michelle (26 June 2012). Along the Path: The Meditator's Companion to the Buddha's Land. Pariyatti. ISBN 9781928706564.

- Chandra (2008)

- J.M. Kenoyer (2006), "Cultures and Societies of the Indus Tradition. In Historical Roots" in the Making of ‘the Aryan’, R. Thapar (ed.), pp. 21–49. New Delhi, National Book Trust.

- Roy, Kaushik (2015). Military Manpower, Armies and Warfare in South Asia. Routledge. p. 27. ISBN 9781317321279.

- Kulke, Hermann; Rothermund, Dietmar (2016). A History of India. Routledge. p. 110. ISBN 9781317242123.

- John Marshall, A Guide to Sanchi, 1918 p. 58ff (Public Domain text)

- Brown, Percy (1959). Indian Architecture (Buddhist And Hindu). pp. 3–5.

- The Calcutta University (1923). Proceedinds And Transactions Of The Second Oriental Conference (1923).

- Spooner, Brainerd (1924). Annual Report Of The Archaeological Survey Of India 1921-22.

- Chandra, Ramaprasad (1927). Memoirs of the archaeological survey of India no.30.

- Paul Gwynne (30 May 2017). World Religions in Practice: A Comparative Introduction. Wiley. pp. 51–52. ISBN 978-1-118-97228-1.

- Jules Barthélemy Saint-Hilaire (1914). The Buddha and His Religion. Trübner. pp. 376–377.

- Digha Nikaya 16, Maha-Parinibbana Sutta, Last Days of the Buddha, Buddhist Publication Society

- Kailash Chand Jain (1991). Lord Mahāvīra and His Times. Motilal Banarsidass. p. 66. ISBN 978-81-208-0805-8.

- Chakrabartia, Dilip K (1976). "Rājagriha: An early historic site in East India". World Archaeology. 7 (3): 261–268. doi:10.1080/00438243.1976.9979639.

- Buddhist Architecture, Lee Huu Phuoc, Grafikol 2009, pp. 97–99

- Le, Huu Phuoc (2010). Buddhist Architecture. Grafikol. pp. 48–49. ISBN 9780984404308.

- "The rubble-built building complex of Jivakamravana at Rajgir probably represents one of the earliest monasteries of India dating from the Buddha's time." in Mishra, Phanikanta; Mishra, Vijayakanta (1995). Researches in Indian archaeology, art, architecture, culture and religion: Vijayakanta Mishra commemoration volume. Sundeep Prakashan. p. 178. ISBN 9788185067803.

- Tadgell, Christopher (2015). The East: Buddhists, Hindus and the Sons of Heaven. Routledge. p. 498. ISBN 9781136753831.

- Handa, O. C.; Hāṇḍā, Omacanda (1994). Buddhist Art & Antiquities of Himachal Pradesh, Upto 8th Century A.D. Indus Publishing. p. 162. ISBN 9788185182995.

- Monuments of Bihar. Department of Art, Culture & Youth, Government of Bihar. 2011. pp. Jivakarama vihara entry.

- Encyclopædia Britannica (2008), Pagoda.

- Buddhist Architecture, Lee Huu Phuoc, Grafikol 2009, pp. 140–174

- Buddhist Architecture, Lee Huu Phuoc, Grafikol 2009, p. 143

- Mishra, Susan Verma; Ray, Himanshu Prabha (5 August 2016). The Archaeology of Sacred Spaces: The temple in western India, 2nd century BCE–8th century CE. Routledge. ISBN 978-1-317-19374-6.

- Schug, Gwen Robbins; Walimbe, Subhash R. (13 April 2016). A Companion to South Asia in the Past. John Wiley & Sons. ISBN 978-1-119-05537-2.

- Khare, M. D. (1975). "The Heliodorus Pillar—A Fresh Appraisal, by John Irwin ( Aarp—Art and Archaeology Research Papers—December 1974 ) A Rejoinder". Proceedings of the Indian History Congress. 36: 92–97. ISSN 2249-1937. JSTOR 44138838.

- Agrawala, Vasudeva S. (1977). Gupta Art Vol.ii.

- Piercey & Scarborough (2008)

- See Stanley Finger (2001), Origins of Neuroscience: A History of Explorations Into Brain Function, Oxford University Press, p. 12, ISBN 0-19-514694-8.

- The Early History of India by Vincent A. Smith

- Annual report 1906–07 p. 89

- Sen, Joyanto. "THE COLOSSAL STŪPA AT NANDANGARH, ITS RECONSTRUCTION AND SIGNIFICANCE". Cite journal requires

|journal=(help) - Ashoka in Ancient India by Nayanjot Lahiri p. 231

- Buddhist architecture, Lee Huu Phuoc, Grafikol 2009, pp. 98–99

- "Ajanta Caves". UNESCO World Heritage Centre. Retrieved 12 March 2019.

- Livingston & Beach, xxiii

- Centre, UNESCO World Heritage. "Buddhist Monuments at Sanchi". UNESCO World Heritage Centre. Retrieved 23 March 2019.

- Buddhist Architecture, Lee Huu Phuoc, Grafikol 2009, pp. 149- –150

- "De l'Indus a l'Oxus: archaeologie de l'Asie Centrale", Pierfrancesco Callieri, p212: "The diffusion, from the second century BCE, of Hellenistic influences in the architecture of Swat is also attested by the archaeological searches at the sanctuary of Butkara I, which saw its stupa "monumentalized" at that exact time by basal elements and decorative alcoves derived from Hellenistic architecture".

- Encyclopædia Britannica (2008), torii

- Japanese Architecture and Art Net Users System (2001), torii.

- Didactic Narration: Jataka Iconography in Dunhuang with a Catalogue of Jataka Representations in China, Alexander Peter Bell, LIT Verlag Münster, 2000 p. 15ff

- World Heritage Monuments and Related Edifices in India, Volume 1 p. 50 by Alī Jāvīd, Tabassum Javeed, Algora Publishing, New York

- Le Huu Phuoc, 2009, pp. 233–237

- "Sowing the Seeds of the Lotus: A Journey to the Great Pilgrimage Sites of Buddhism, Part I" by John C. Huntington. Orientations, November 1985 p. 61

- Buddhist Architecture, Huu Phuoc Le, Grafikol, 2010 p. 240

- A Global History of Architecture, Francis D. K. Ching, Mark M. Jarzombek, Vikramaditya Prakash, John Wiley & Sons, 2017 p. 570ff

- Hardy, Adam (1995). Indian Temple Architecture: Form and Transformation : the Karṇāṭa Drāviḍa Tradition, 7th to 13th Centuries. Abhinav Publications. p. 39. ISBN 9788170173120.

- Le, Huu Phuoc (2010). Buddhist Architecture. Grafikol. p. 238. ISBN 9780984404308.

- Buddhist Architecture, Lee Huu Phuoc, Grafikol 2009, p. 147

- Abram, David; (Firm), Rough Guides (2003). The Rough Guide to India. Rough Guides. ISBN 9781843530893.

- Marshall, John (1955). Guide to Sanchi.

- Le, Huu Phuoc (2010). Buddhist Architecture. Grafikol. p. 237. ISBN 9780984404308.

- Le Huu Phuoc, Buddhist Architecture, pp. 238–248

- Le Huu Phuoc, Buddhist Architecture, p. 234

- 2500 Years of Buddhism by P.V. Bapat, p. 283

- Encyclopædia Britannica (2008), education, history of.

- Shastri, K.A. Age Of The Nandas And Mauryas. p. 339.

- Gosh, A. (1964). Indian Archaeology: A review 1961-62. New Dehli: Archaeological survey of India. pp. 50–52.

- Murthy, K. Krishna (1977). Nagarjunakonda A Cultural Study. Concept Publishing Company.

- Sharma, G. R. (1977). Kusana studies.

- Varadpande, Manohar Laxman (1987). History of Indian Theatre. Abhinav Publications. ISBN 9788170172215.

- Varadpande, M. L. (1981). Ancient Indian And Indo-Greek Theatre. Abhinav Publications. ISBN 9788170171478.

- M. N, Deshpande (1975). Indian archaeology: A review 1966-67. Calcutta: Archaeological survey of India. pp. 45–46.

- "EARLY FORTIFICATION: AIHOLE, BADAMI, PATTADAKAL, MAHAKUTA AND ALAMPUR" (PDF).

- Behrendt, Kurt A. (2004). Handbuch der Orientalistik. BRILL. ISBN 9789004135956.

- Early Buddhist Transmission and Trade Networks by Jason Neelis p. 168

- The Spread of Buddhism by Ann Heirman, Stephan Peter Bumbacher p. 60 sq

- The First Spring: The Golden Age of India by Abraham Eraly p. 48 sq

- Ancient Indian History and Civilization by Sailendra Nath Sen p. 221

- A Comprehensive History Of Ancient India p. 174

- Centre, UNESCO World Heritage. "Group of Monuments at Pattadakal". UNESCO World Heritage Centre. Retrieved 23 March 2019.

- "Archaeological Site of Nalanda Mahavihara at Nalanda, Bihar". UNESCO World Heritage Centre. Retrieved 23 March 2019.

- K. D. Bajpai (2006). History of Gopāchala. Bharatiya Jnanpith. p. 31. ISBN 978-81-263-1155-2.

- "Great Living Chola Temples". UNESCO World Heritage Centre. Retrieved 12 March 2019.

- Lemoy, Christian (2011). Across the Pacific: From Ancient Asia to Precolombian America. Christian Lemoy. ISBN 9781599425825.

- Rowland, 44-45, 64-65, 113, 218-219; Harle, 48, 175

- Michell, 82

- Michell, 84

- Harle, 530, note 3 to chapter 30. See also 489, note 10

- Harle, 493, note 5

- Cunningham, Alexander (1892). Mahâbodhi, or the great Buddhist temple under the Bodhi tree at Buddha-Gaya. London: W. H. Allen. p. 85.

- Robinson, Andrew (15 November 2015). The Indus: Lost Civilizations. Reaktion Books. ISBN 9781780235417.

- Tripathi, Vibha (27 February 2018). "METALS AND METALLURGY IN THE HARAPPAN CIVILIZATION" (PDF). Indian Journal of History of Science: 279–295.

- Kenoyer, J.M; Dales, G. F. Summaries of Five Seasons of Research at Harappa (District Sahiwal, Punjab, Pakistan) 1986-1990. Prehistory Press. pp. 185–262.

- Kenoyer, J.M.; Miller, Heather M..L. Metal Technologies of the Indus Valley Tradition in Pakistan and Western India (PDF). p. 124.

- Proceedinds And Transactions Of The Second Oriental Conference (1923). 1923. pp. 86.

- The Calcutta Review Vol.10, No.1-3(april-june)1924. 1924. p. 140.

- Dubey, Lal Mani (1978). "Some Observations on the Vesara School of Hindu Architecture". Proceedings of the Indian History Congress. 39: 1000–1006. ISSN 2249-1937. JSTOR 44139449.

- Meister, Michael W. (26 July 2010). Temples of the Indus: Studies in the Hindu Architecture of Ancient Pakistan. BRILL. ISBN 9789004190115.

- Wright, Colin. "Front view of a ruined temple, with sculptured slabs in foreground, Deo Baranark". www.bl.uk. Retrieved 23 April 2019.

- "General view of ruined temple at Deo Baranark". Europeana Collections. Retrieved 23 April 2019.

- Le, Huu Phuoc (2010). Buddhist Architecture. USA: Grafikol. pp. 246–247. ISBN 978-0984404308.

- Rowland, 163-164

- Gosh, A. (1964). Indian Archaeology: A review 1961-62. New Dehli: Archaeological survey of India. pp. 50–52.

- District Gazetteers Of The United Provinces Of Agra And Oudh Cawnpore Vol Xix. p. 190.

.jpg.webp)

.jpg.webp)

.jpg.webp)