Hindu architecture

Hindu architecture is the traditional system of Indian architecture for structures such as temples, monasteries, statues, homes, market places, gardens and town planning as described in Hindu texts.[1][2] The architectural guidelines survive in Sanskrit manuscripts and in some cases also in other regional languages. These texts include the Vastu shastras, Shilpa Shastras, the Brihat Samhita, architectural portions of the Puranas and the Agamas, and regional texts such as the Manasara among others.[3][4]

| Part of a series on |

| Hinduism |

|---|

|

|

By far the most important, characteristic and numerous surviving examples of Hindu architecture are Hindu temples, with an architectural tradition that has left surviving examples in stone, brick, and rock-cut architecture dating back to the Gupta Empire.

There is far fewer surviving secular Hindu architecture such as palaces, homes and cities. Very little early palace architecture survives, and the great majority of surviving palaces show clear influence from Indo-Islamic architecture, especially Mughal architecture, later joined by European architecture.

Texts

Vaastu Shastras and Shilpa Shastras are listed as one of 64 divine arts in ancient Indian texts. They are design manuals covering the art and science of architecture, typically mixing form, function with Hindu symbolism.[1][2] The earliest, archaic and distilled version of Hindu architecture principles are found in the Vedic literature, traditionally considered as the Upavedas (lesser appendices to the Vedas), and called the Sthapatya Veda.[5] Acharya's Encyclopedia of Hindu Architecture lists hundreds of Sanskrit manuscripts with more details on Hindu architecture that have survived into the modern age.[1] They cover the architectural aspects of a wide range of subjects: ornaments, furniture, vehicles (wagons, carts), gateways, water tanks, drains, cities, streets, homes, palaces, temples and others.[1][2] The most studied texts in the contemporary era are Sanskrit manuscripts in different Indic scripts. These include the Brihat Samhita (chapters 53, 56–58 and 79), the Manasara Shilpa Sastra, the Mayamata Vastu Sastra with commentaries in Telugu and Tamil, the Puranas (for example, chapters 42–62 and 104–106 of Agni Purana, chapter 7 of Brahmanda Purana) and the Hindu Agamas.[6]

Villages, towns and cities

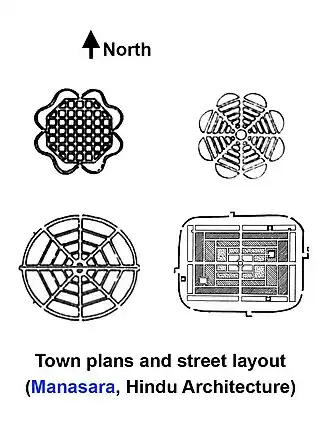

Hindu texts recommend architectural guidelines for homes, market places, gardens and town planning.[1][7] The best site for human settlement, declares Manasara, seeks the right terrain with thick soil that slopes to open skies eastward so that the residents can appreciate the sunrise.[9] It is near a river or significant water stream, and has enough ground water for wells – a second source of water.[9] The soil, states Manasara, should be firm, rich for growing flowers, vegetables and fruit trees, and of agreeable odor. The text recommends that the town planners dig and check the soil quality for a stable foundation to homes and public buildings.[9] Once the location is accepted, the text describes forty plans for laying out the streets, the homes, markets, gardens and other infrastructure necessary for the settlement. Example architectural plans include Dandaka, Prastara, Chaturmukha, Padmaka, Karmuka, Swastika and others.[7] The Hindu texts vary, with five shared principles:[10]

- Diknirnaya: principles of orientation

- Padavinyasa : site planning

- Hastalakshana : proportionate measurement ratios of sections

- Ayadi : six canonical principles of architecture

- Patakadi : aesthetics or character of each building or part of the overall plan

The guidelines combine principles of early Hindu understanding of science, spiritual beliefs, astrology and astronomy.[10] In practice, these guidelines favor symmetry set to the cardinal directions, with many plans favoring the streets to be aligned with seasonal winds direction, integrated with the terrain and the needs of the local weather.[9][10] A temple or public assembly hall at the center of the town is recommended in Manasara.[9]

Temples (mandirs)

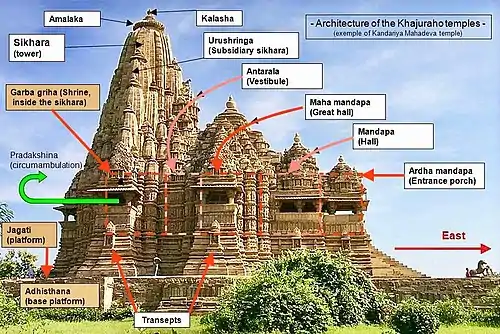

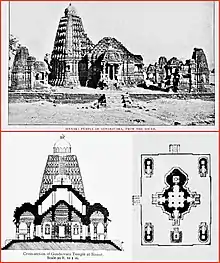

Hindu temple architecture has many varieties of style whose historic role has been to provide "a focus for both the social and spiritual life" for the Hindu community it serves, states George Michell.[11] Every Hindu temple ("mandir") is imbued with symbolism, yet the basic structure of each remains the same. Each temple has an inner sanctum or the sacred space, the garbha griha or womb-chamber, where the primary murti or the image of a deity is housed in a simple bare cell for darshana (view, meditative focus).[12] Above the garbhagriha is a tower-like shikhara, called the vimana in south India. This sanctum is surrounded by a closed or open path for pradakshina (also called parikrama, circumambulation) that is typically intricately carved with symbolic art depicting Hindu legends, themes of artha, dharma and kama as well as the statues of significant deities of three major Hindu traditions (Vishnu, Shiva and Shakti).[13]

The sanctums of significant temples have a mandapa congregation hall, and sometimes an antarala antechamber and porch between garbhagriha and mandapa. Major temples that attract pilgrims from far typically have mandapas or other buildings that service the pilgrims. These may be connected or detached from the temple. The main temple may exist with other smaller temples or shrines in the temple compound. The streets around the temple are markets and hubs of economic activity.[13] There are examples of special dance pavilions (Nata Mandir), like in the Konark Sun Temple. The pool, temple tank (Kunda) is also part of large temples, and they traditionally have served as a place for a bath dip and ablutions for pilgrims.[14] The same essential architectural principles are found in the historic Hindu temples of southeast Asia.[15]

Gopurams

Essentially independent architectural structure is an element of the temple complex as gopuram, viz., gatehouse towers, usually ornate, othen with colossal size, at the entrance of a Hindu temple of Southern India.[16]

Monasteries (mathas)

Hindu monasteries such as Mathas and hermitages (Ashrams) are complexes of buildings include temples, monastic cells or the communal house and ancillary facilities.[17] In some currents of Hinduism, places of pilgrimage have become Bhajana Kutir, viz., meditation huts of the saints.

Rathas

In some Hindu sites, there are shrines or buildings named rathas because they have the shape of a huge chariot.[18]

Toranas (archways)

Torana is a free-standing archway for ceremonial purposes seen in the Hindu, Buddhist and Jain architecture in front of the temples, monasteries and other objects, sometimes as single building.[19][20]

Stambhas (columns)

Stambha denotes a pillar or column, and is also known as jangha, stali, angrika, sthanu, arani, bharaka or dharana.[21] It is described in Manasara to consist of a pedestal, base, column and a capital. It can be made from wood or stone, be independent or be a pilaster joined to one of the walls. The text describes different proportions for different materials of construction.[21] The length of column is divided intomatras (portions), and these may be decorated with artwork. The Manasara suggests rules for tapering the top portions of the stambha.[21] Illustrative stambhas include the Vijay Stambha (Tower of victory) at Chittorgarh fort, Rajasthan. It is dedicated to Vishnu.

«Dhvaja-stambhas» are founding at the entrance of temples as flagstaffs, often with the image of lingam and sacred animals.

Chhatris

Chhatris are elevated, dome-shaped pavilions used as an element in Indian architecture, originating in Rajasthani architecture. They are widely used in palaces, in forts, or to demarcate funerary sites, etc.

Gallery

- Some folios from surviving manuscripts on Hindu architecture

Drawing and notes on water tank fountain

Drawing and notes on water tank fountain Drawing and notes on water tank fountain, part 2

Drawing and notes on water tank fountain, part 2 A mandala in Vastu Sastra Hiti Dayeka

A mandala in Vastu Sastra Hiti Dayeka Two leaves in Samkrantiyajnavidhi illustrating proportions for Harihara – half Shiva, half Vishnu.

Two leaves in Samkrantiyajnavidhi illustrating proportions for Harihara – half Shiva, half Vishnu. A Vastu sastra page on home design, first line mentions vastu sastra

A Vastu sastra page on home design, first line mentions vastu sastra

- Some temples and public stepwell

Lingaraja Temple (Bhubaneswar, Odisha)

Lingaraja Temple (Bhubaneswar, Odisha) Chennakeshava Temple, Belur (Karnataka)

Chennakeshava Temple, Belur (Karnataka) Lalji temple (Bishnupur, Bankura, West Bengal)

Lalji temple (Bishnupur, Bankura, West Bengal) Nata Mandir of Konark Sun Temple (Odisha)

Nata Mandir of Konark Sun Temple (Odisha) Meenakshiamman Temple Gopuram (Madurai, Tamil Nadu)

Meenakshiamman Temple Gopuram (Madurai, Tamil Nadu) Rani ka vav Gujarat, a historic public water tank with Hindu arts

Rani ka vav Gujarat, a historic public water tank with Hindu arts Advaita Vedanta Monastery (Sringeri, Karnataka)

Advaita Vedanta Monastery (Sringeri, Karnataka) Pancha Rathas (Mahabalipuram, Tamil Nadu)

Pancha Rathas (Mahabalipuram, Tamil Nadu)Torana.jpg.webp) Sahastra Bahu Temples Torana (Nagda, Rajasthan)

Sahastra Bahu Temples Torana (Nagda, Rajasthan) Torana of Mukteshvara Temple, Bhubaneswar (Orisha)

Torana of Mukteshvara Temple, Bhubaneswar (Orisha)

See also

References

- Acharya 1927, p. xviii-xx.

- Sinha, Amita (1998). "Design of Settlements in the Vaastu Shastras". Journal of Cultural Geography. Taylor & Francis. 17 (2): 27–41. doi:10.1080/08873639809478319.

- Acharya 1927, p. xviii-xx, Appendix I lists hundreds of Hindu architectural texts.

- Shukla 1993.

- Patra, Reena (2006). "A Comparative Study on Vaastu Shastra and Heidegger's 'Building, Dwelling and Thinking'". Asian Philosophy. Taylor & Francis. 16 (3): 199–218. doi:10.1080/09552360600979430. S2CID 144592593.

- Acharya 1927, p. xviii-xx with Appendix 1.

- Sinha 1998, pp. 27–40.

- Ram Raz 1834.

- Ernest Havell 1972, pp. 7–17.

- Patra 2006, pp. 201–203.

- Michell 1988, p. 14.

- Shilpa Sharma & Shireesh Deshpande 2017, pp. 309-317.

- Michell 1988, pp. 66–76, 86–126.

- Acharya 2010, p. 74.

- Michell 1988, pp. 159–182.

- "Gopura". Encyclopædia Britannica. Retrieved 2008-01-20.

- Sears 2014, pp. 4—9.

- Harle 1994, p. 153.

- Hardy, Adam (2003). "Toraṇa". Grove Art. doi:10.1093/gao/9781884446054.article.T085631. Retrieved 2018-08-08.

- Dhar 2010.

- Acharya 2010, p. 533.

Bibliography

- Acharya, P. K. (2010). An encyclopaedia of Hindu architecture. New Delhi: Oxford University Press (Republished by Motilal Banarsidass). ISBN 978-81-85990-03-3.

- Acharya, P. K. (1927). Indian Architecture according to the Manasara Shilpa Shastra. London: Oxford University Press (Republished by Motilal Banarsidass). ISBN 0300062176.

- Dhar, P. D. (2010). The Torana in Indian and Southeast Asian Architecture. New Delhi: D K Printworld. ISBN 978-8124605349.

- Glushkova, I. (2014). Objects of Worship in South Asian Religions: Forms, Practices and Meanings. Routledge. ISBN 978-1-317-67595-2.

- Goel, S. R. (1991). Hindu Temples – What Happened to Them. 2. New Delhi: Voice of India. ISBN 81-85990-03-4.

- Harle, J. C. (1994). The Art and Architecture of the Indian Subcontinent (2nd ed.). Yale University Press Pelican History of Art. ISBN 0300062176.

- Ernest Havell (1972). The Ancient and Medieval Architecture of India. John Murray, London (Reprinted S. Chand).

- Juneja, M. (2001). Architecture in Medieval India: Forms, Contexts, Histories (2nd ed.). Orient Blackswan. ISBN 978-8178242286.

- Michell, G. (1988). The Hindu Temple: An Introduction to its Meaning and Forms (2nd ed.). Chicago/London: University of Chicago Press. ISBN 0-226-53230-5.

- Patra, Reena (2006). "A Comparative Study on Vaastu Shastra and Heidegger's 'Building, Dwelling and Thinking'". Asian Philosophy. Taylor & Francis. 16 (3): 199–218. doi:10.1080/09552360600979430. S2CID 144592593. Text "harv" ignored (help)

- Ram Raz (1834). Essay on the Architecture of the Hindús. Royal Asiatic Society of Great Britain and Ireland.

- Shilpa Sharma; Shireesh Deshpande (2017). "Architectural Strategies Used in Hindu Temples to Emphasize Sacredness". Journal of Architectural and Planning Research. 34 (4): 309–319. JSTOR 44987239.

- Sinha, Amita (1998). "Design of Settlements in the Vaastu Shastras". Journal of Cultural Geography. Taylor & Francis. 17 (2): 27–41. doi:10.1080/08873639809478319. Text "harv" ignored (help)

- Shukla, D. N. (1993). Vastu-Sastra: Hindu Science of Architecture. Munshiram Manoharial Publishers. ISBN 978-81-215-0611-3.

- Sears, T. (2014). Worldly Gurus and Spiritual Kings: Architecture and Asceticism in Medieval India. Yale University Press. ISBN 978-0-300-19844-7.

- Thapar, B. (2004). Introduction to Indian Architecture. Singapore: Periplus Editions. ISBN 0-7946-0011-5.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Hindu architecture. |

- Vijayanagara architecture

- Sthapatyaveda (Temple Architecture) on Hindupedia, the Hindu Encyclopedia