Allah

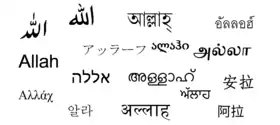

Allah (/ˈælə, ˈɑːlə, əˈlɑː/;[1][2] Arabic: الله, romanized: Allāh, IPA: [ʔaɫ.ɫaːh] (![]() listen)) is the Arabic word for God in Abrahamic religions. In the English language, the word generally refers to God in Islam.[3][4][5] The word is thought to be derived by contraction from al-ilāh, which means "the god", and is linguistically related to El (Elohim) and Elah, the Hebrew and Aramaic words for God.[6][7]

listen)) is the Arabic word for God in Abrahamic religions. In the English language, the word generally refers to God in Islam.[3][4][5] The word is thought to be derived by contraction from al-ilāh, which means "the god", and is linguistically related to El (Elohim) and Elah, the Hebrew and Aramaic words for God.[6][7]

The word Allah has been used by Arabic people of different religions since pre-Islamic times.[8] More specifically, it has been used as a term for God by Muslims (both Arab and non-Arab) and Arab Christians.[9] It is also often, albeit not exclusively, used in this way by Bábists, Baháʼís, Mandaeans, Indonesian and Maltese Christians, and Mizrahi Jews.[10][11][12][13] Similar usage by Christians and Sikhs in West Malaysia has recently led to political and legal controversies.[14][15][16][17]

Etymology

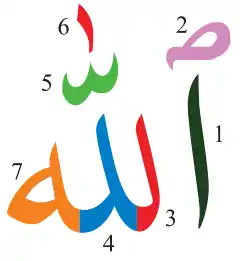

- alif

- hamzat waṣl (همزة وصل)

- lām

- lām

- shadda (شدة)

- dagger alif (ألف خنجرية)

- hāʾ

The etymology of the word Allāh has been discussed extensively by classical Arab philologists.[18] Grammarians of the Basra school regarded it as either formed "spontaneously" (murtajal) or as the definite form of lāh (from the verbal root lyh with the meaning of "lofty" or "hidden").[18] Others held that it was borrowed from Syriac or Hebrew, but most considered it to be derived from a contraction of the Arabic definite article al- "the" and ilāh "deity, god" to al-lāh meaning "the deity", or "the God".[18] The majority of modern scholars subscribe to the latter theory, and view the loanword hypothesis with skepticism.[19]

Cognates of the name "Allāh" exist in other Semitic languages, including Hebrew and Aramaic.[20] The corresponding Aramaic form is Elah (אלה), but its emphatic state is Elaha (אלהא). It is written as ܐܠܗܐ (ʼĔlāhā) in Biblical Aramaic and ܐܲܠܵܗܵܐ (ʼAlâhâ) in Syriac as used by the Assyrian Church, both meaning simply "God".[21] Biblical Hebrew mostly uses the plural (but functional singular) form Elohim (אלהים), but more rarely it also uses the singular form Eloah (אלוהּ).

Usage

Pre-Islamic Arabians

| Deities of the ancient Near East |

|---|

| Religions of the ancient Near East |

Regional variants of the word Allah occur in both pagan and Christian pre-Islamic inscriptions.[8][22] Different theories have been proposed regarding the role of Allah in pre-Islamic polytheistic cults. Some authors have suggested that polytheistic Arabs used the name as a reference to a creator god or a supreme deity of their pantheon.[23][24] The term may have been vague in the Meccan religion.[23][25] According to one hypothesis, which goes back to Julius Wellhausen, Allah (the supreme deity of the tribal federation around Quraysh) was a designation that consecrated the superiority of Hubal (the supreme deity of Quraysh) over the other gods.[8] However, there is also evidence that Allah and Hubal were two distinct deities.[8] According to that hypothesis, the Kaaba was first consecrated to a supreme deity named Allah and then hosted the pantheon of Quraysh after their conquest of Mecca, about a century before the time of Muhammad.[8] Some inscriptions seem to indicate the use of Allah as a name of a polytheist deity centuries earlier, but nothing precise is known about this use.[8] Some scholars have suggested that Allah may have represented a remote creator god who was gradually eclipsed by more particularized local deities.[26][27] There is disagreement on whether Allah played a major role in the Meccan religious cult.[26][28] No iconic representation of Allah is known to have existed.[28][29] Allah is the only god in Mecca that did not have an idol.[30] Muhammad's father's name was ʿAbd-Allāh meaning "the slave of Allāh".[25]

Christianity

Arabic-speakers of all Abrahamic faiths, including Christians and Jews, use the word "Allah" to mean "God".[10] The Christian Arabs of today have no other word for "God" than "Allah".[31] Similarly, the Aramaic word for "God" in the language of Assyrian Christians is ʼĔlāhā, or Alaha. (Even the Arabic-descended Maltese language of Malta, whose population is almost entirely Catholic, uses Alla for "God".) Arab Christians, for example, use the terms Allāh al-ab (الله الأب) for God the Father, Allāh al-ibn (الله الابن) for God the Son, and Allāh ar-rūḥ al-quds (الله الروح القدس) for God the Holy Spirit. (See God in Christianity for the Christian concept of God.)

Arab Christians have used two forms of invocations that were affixed to the beginning of their written works. They adopted the Muslim bismillāh, and also created their own Trinitized bismillāh as early as the 8th century.[32] The Muslim bismillāh reads: "In the name of God, the Compassionate, the Merciful." The Trinitized bismillāh reads: "In the name of Father and the Son and the Holy Spirit, One God." The Syriac, Latin and Greek invocations do not have the words "One God" at the end. This addition was made to emphasize the monotheistic aspect of Trinitarian belief and also to make it more palatable to Muslims.[32]

According to Marshall Hodgson, it seems that in the pre-Islamic times, some Arab Christians made pilgrimage to the Kaaba, a pagan temple at that time, honoring Allah there as God the Creator.[33]

Some archaeological excavation quests have led to the discovery of ancient pre-Islamic inscriptions and tombs made by Arab Christians in the ruins of a church at Umm el-Jimal in Northern Jordan, which initially, according to Enno Littman (1949), contained references to Allah as the proper name of God. However, on a second revision by Bellamy et al. (1985 & 1988) the 5-versed-inscription was re-translated as "(1)This [inscription] was set up by colleagues of ʿUlayh, (2) son of ʿUbaydah, secretary (3) of the cohort Augusta Secunda (4) Philadelphiana; may he go mad who (5) effaces it."[34][35][36]

The syriac word ܐܠܗܐ (ʼĔlāhā) can be found in the reports and the lists of names of Christian martyrs in South Arabia,[37][38] as reported by antique Syriac documents of the names of those martyrs from the era of the Himyarite and Aksumite kingdoms[39]

In Ibn Ishaq's biography there is a Christian leader named Abd Allah ibn Abu Bakr ibn Muhammad, who was martyred in Najran in 523, as he had worn a ring that said "Allah is my lord".[40]

In an inscription of Christian martyrion dated back to 512, references to 'l-ilah (الاله)[41] can be found in both Arabic and Aramaic. The inscription starts with the statement "By the Help of 'l-ilah".[42][43]

In pre-Islamic Gospels, the name used for God was "Allah", as evidenced by some discovered Arabic versions of the New Testament written by Arab Christians during the pre-Islamic era in Northern and Southern Arabia.[44] However most recent research in the field of Islamic Studies by Sydney Griffith et al. (2013), David D. Grafton (2014), Clair Wilde (2014) & ML Hjälm et al. (2016 & 2017) assert that "all one can say about the possibility of a pre-Islamic, Christian version of the Gospel in Arabic is that no sure sign of its actual existence has yet emerged."[45][46][47][48][49] Additionally ML Hjälm in her most recent research (2017) inserts that "manuscripts containing translations of the gospels are encountered no earlier than the year 873"[50]

Irfan Shahîd quoting the 10th-century encyclopedic collection Kitab al-Aghani notes that pre-Islamic Arab Christians have been reported to have raised the battle cry "Ya La Ibad Allah" (O slaves of Allah) to invoke each other into battle.[51] According to Shahid, on the authority of 10th-century Muslim scholar Al-Marzubani, "Allah" was also mentioned in pre-Islamic Christian poems by some Ghassanid and Tanukhid poets in Syria and Northern Arabia.[52][53][54]

Islam

In Islam, Allah is the unique, omnipotent and only deity and creator of the universe and is equivalent to God in other Abrahamic religions.[11][12] Allah is usually seen as the personal name of God, a notion which became disputed in contemporary scholarship, including the question, whether or not the word Allah should be translated as God.[55]

According to Islamic belief, Allah is the most common word to represent God,[56] and humble submission to his will, divine ordinances and commandments is the pivot of the Muslim faith.[11] "He is the only God, creator of the universe, and the judge of humankind."[11][12] "He is unique (wāḥid) and inherently one (aḥad), all-merciful and omnipotent."[11] The Qur'an declares "the reality of Allah, His inaccessible mystery, His various names, and His actions on behalf of His creatures."[11]

The concept correlates to the Tawhid, where chapter 112 of the Qur'an (Al-'Ikhlās, The Sincerity) reads:

and in the Ayat ul-Kursi ("Verse of the Throne"), which is the 255th verse and the powerful verse in the longest chapter (the 2nd chapter) of the Qur'an, Al-Baqarah ("The Cow") states:

"Allah! There is no deity but Him, the Alive, the Eternal. Neither slumber nor sleep overtaketh Him.

Unto Him belongeth whatsoever is in the heavens and whatsoever is in the earth. Who could intercede in His presence without His permission?

He knoweth that which is in front of them and that which is behind them, while they encompass nothing of His knowledge except what He wills.

His throne includeth the heavens and the earth, and He is never weary of preserving them.

He is the Sublime, the Tremendous."

In Islamic tradition, there are 99 Names of God (al-asmā' al-ḥusná lit. meaning: 'the best names' or 'the most beautiful names'), each of which evoke a distinct characteristic of Allah.[12][59] All these names refer to Allah, the supreme and all-comprehensive divine name.[60] Among the 99 names of God, the most famous and most frequent of these names are "the Merciful" (ar-Raḥmān) and "the Compassionate" (ar-Raḥīm),[12][59] including the forementioned above al-Aḥad ("the One, the Indivisible") and al-Wāḥid ("the Unique, the Single").

Most Muslims use the untranslated Arabic phrase in shā’a llāh (meaning 'if God wills') after references to future events.[61] Muslim discursive piety encourages beginning things with the invocation of bi-smi llāh (meaning 'In the name of God').[62] There are certain phrases in praise of God that are favored by Muslims, including "Subḥāna llāh" (Glory be to God), "al-ḥamdu li-llāh" (Praise be to God), "lā ilāha illā llāh" (There is no deity but God) or sometimes "lā ilāha illā inta/ huwa" (There is no deity but You/ Him) and "Allāhu Akbar" (God is the Most Great) as a devotional exercise of remembering God (dhikr).[63]

In a Sufi practice known as dhikr Allah (Arabic: ذكر الله, lit. "Remembrance of God"), the Sufi repeats and contemplates the name Allah or other associated divine names to Him while controlling his or her breath.[64] For example, in countless references in the context from the Qur'an forementioned above:

1) Allah is referred to in the second person pronoun in Arabic as "Inta (Arabic: َإِنْت)" like the English "You", or commonly in the third person pronoun "Huwa (Arabic: َهُو)" like the English "He" and uniquely in the case pronoun of the oblique form "Hu/ Huw (Arabic: هو /-هُ)" like the English "Him" which rhythmically resonates and is chanted as considered a sacred sound or echo referring Allah as the "Absolute Breath or Soul of Life" - Al-Nafs al-Hayyah (Arabic: النّفس الحياة, an-Nafsu 'l-Ḥayyah) - notably among the 99 names of God, "the Giver of Life" (al-Muḥyī) and "the Bringer of Death" (al-Mumiyt);

2) Allah is neither male or female (who has no gender), but who is the essence of the "Omnipotent, Selfless, Absolute Soul (an-Nafs, النّفس) and Holy Spirit" (ar-Rūḥ, الرّوح) - notably among the 99 names of God, "the All-Holy, All-Pure and All-Sacred" (al-Quddus);

3) Allah is the originator of both before and beyond the cycle of creation, destruction and time, - notably among the 99 names of God, "the First, Beginning-less" (al-Awwal), "the End/ Beyond ["the Final Abode"]/ Endless" (al-Akhir/ al-Ākhir) and "the Timeless" (aṣ-Ṣabūr).

According to Gerhard Böwering, in contrast with pre-Islamic Arabian polytheism, God in Islam does not have associates and companions, nor is there any kinship between God and jinn.[56] Pre-Islamic pagan Arabs believed in a blind, powerful, inexorable and insensible fate over which man had no control. This was replaced with the Islamic notion of a powerful but provident and merciful God.[11]

According to Francis Edward Peters, "The Qur’ān insists, Muslims believe, and historians affirm that Muhammad and his followers worship the same God as the Jews (29:46). The Qur’an's Allah is the same Creator God who covenanted with Abraham". Peters states that the Qur'an portrays Allah as both more powerful and more remote than Yahweh, and as a universal deity, unlike Yahweh who closely follows Israelites.[65]

Pronunciation

The word Allāh is generally pronounced [ɑɫˈɫɑː(h)], exhibiting a heavy lām, [ɫ], a velarized alveolar lateral approximant, a marginal phoneme in Modern Standard Arabic. Since the initial alef has no hamza, the initial [a] is elided when a preceding word ends in a vowel. If the preceding vowel is /i/, the lām is light, [l], as in, for instance, the Basmala.[66]

As a loanword

English and other European languages

The history of the name Allāh in English was probably influenced by the study of comparative religion in the 19th century; for example, Thomas Carlyle (1840) sometimes used the term Allah but without any implication that Allah was anything different from God. However, in his biography of Muḥammad (1934), Tor Andræ always used the term Allah, though he allows that this "conception of God" seems to imply that it is different from that of the Jewish and Christian theologies.[67]

Languages which may not commonly use the term Allah to denote God may still contain popular expressions which use the word. For example, because of the centuries long Muslim presence in the Iberian Peninsula, the word ojalá in the Spanish language and oxalá in the Portuguese language exist today, borrowed from Arabic inshalla (Arabic: إن شاء الله). This phrase literally means 'if God wills' (in the sense of "I hope so").[68] The German poet Mahlmann used the form "Allah" as the title of a poem about the ultimate deity, though it is unclear how much Islamic thought he intended to convey.

Some Muslims leave the name "Allāh" untranslated in English, rather than using the English translation "God".[69] The word has also been applied to certain living human beings as personifications of the term and concept.[70][71]

Malaysian and Indonesian language

Christians in Malaysia and Indonesia use Allah to refer to God in the Malaysian and Indonesian languages (both of them standardized forms of the Malay language). Mainstream Bible translations in the language use Allah as the translation of Hebrew Elohim (translated in English Bibles as "God").[72] This goes back to early translation work by Francis Xavier in the 16th century.[73][74] The first dictionary of Dutch-Malay by Albert Cornelius Ruyl, Justus Heurnius, and Caspar Wiltens in 1650 (revised edition from 1623 edition and 1631 Latin edition) recorded "Allah" as the translation of the Dutch word "Godt".[75] Ruyl also translated the Gospel of Matthew in 1612 into the Malay language (an early Bible translation into a non-European language,[76] made a year after the publication of the King James Version[77][78]), which was printed in the Netherlands in 1629. Then he translated the Gospel of Mark, published in 1638.[79][80]

The government of Malaysia in 2007 outlawed usage of the term Allah in any other but Muslim contexts, but the Malayan High Court in 2009 revoked the law, ruling it unconstitutional. While Allah had been used for the Christian God in Malay for more than four centuries, the contemporary controversy was triggered by usage of Allah by the Roman Catholic newspaper The Herald. The government appealed the court ruling, and the High Court suspended implementation of its verdict until the hearing of the appeal. In October 2013 the court ruled in favor of the government's ban.[81] In early 2014 the Malaysian government confiscated more than 300 bibles for using the word to refer to the Christian God in Peninsular Malaysia.[82] However, the use of Allah is not prohibited in the two Malaysian states of Sabah and Sarawak.[83][84] The main reason it is not prohibited in these two states is that usage has been long-established and local Alkitab (Bibles) have been widely distributed freely in East Malaysia without restrictions for years.[83] Both states also do not have similar Islamic state laws as those in West Malaysia.[17]

In reaction to some media criticism, the Malaysian government has introduced a "10-point solution" to avoid confusion and misleading information.[85][86] The 10-point solution is in line with the spirit of the 18- and 20-point agreements of Sarawak and Sabah.[17]

National flags with Allah written on them

Flag of Saudi Arabia with the Islamic holy creed written on it.

Flag of Saudi Arabia with the Islamic holy creed written on it.

Flag of Iran with Allah written on it.

Flag of Iran with Allah written on it.

Typography

The word Allāh is always written without an alif to spell the ā vowel. This is because the spelling was settled before Arabic spelling started habitually using alif to spell ā. However, in vocalized spelling, a small diacritic alif is added on top of the shaddah to indicate the pronunciation.

One exception may be in the pre-Islamic Zabad inscription,[87] where it ends with an ambiguous sign that may be a lone-standing h with a lengthened start, or may be a non-standard conjoined l-h:-

- الاه: This reading would be Allāh spelled phonetically with alif for the ā.

- الإله: This reading would be al-Ilāh = 'the god' (an older form, without contraction), by older spelling practice without alif for ā.

Many Arabic type fonts feature special ligatures for Allah.[88]

Unicode

Unicode has a code point reserved for Allāh, ﷲ = U+FDF2, in the Arabic Presentation Forms-A block, which exists solely for "compatibility with some older, legacy character sets that encoded presentation forms directly";[89][90] this is discouraged for new text. Instead, the word Allāh should be represented by its individual Arabic letters, while modern font technologies will render the desired ligature.

The calligraphic variant of the word used as the Coat of arms of Iran is encoded in Unicode, in the Miscellaneous Symbols range, at code point U+262B (☫).

Notes

- "Allah". Random House Webster's Unabridged Dictionary.

- "Allah". Oxford Learner's Dictionaries.

- "God". Islam: Empire of Faith. PBS. Archived from the original on 27 March 2014. Retrieved 18 December 2010.

- "Islam and Christianity", Encyclopedia of Christianity (2001): Arabic-speaking Christians and Jews also refer to God as Allāh.

- Gardet, L. "Allah". In Bearman, P.; Bianquis, Th.; Bosworth, C.E.; van Donzel, E.; Heinrichs, W.P. (eds.). Encyclopaedia of Islam Online. Brill Online. Retrieved 2 May 2007.

- Zeki Saritoprak (2006). "Allah". In Oliver Leaman (ed.). The Qur'an: An Encyclopedia. Routledge. p. 34. ISBN 9780415326391.

- Vincent J. Cornell (2005). "God: God in Islam". In Lindsay Jones (ed.). Encyclopedia of Religion. 5 (2nd ed.). MacMillan Reference USA. p. 724.

- Christian Julien Robin (2012). Arabia and Ethiopia. In The Oxford Handbook of Late Antiquity. OUP USA. pp. 304–305. ISBN 9780195336931.

- Merriam-Webster. "Allah". Merriam-Webster. Archived from the original on 20 April 2014. Retrieved 25 February 2012.

- Columbia Encyclopedia, Allah

- "Allah." Encyclopædia Britannica. 2007. Encyclopædia Britannica

- Encyclopedia of the Modern Middle East and North Africa, Allah

- Willis Barnstone, Marvin Meyer The Gnostic Bible: Revised and Expanded Edition Shambhala Publications 2009 ISBN 978-0-834-82414-0 page 531

- Sikhs target of 'Allah' attack, Julia Zappei, 14 January 2010, The New Zealand Herald. Accessed on line 15 January 2014.

- Malaysia court rules non-Muslims can't use 'Allah', 14 October 2013, The New Zealand Herald. Accessed on line 15 January 2014.

- Malaysia's Islamic authorities seize Bibles as Allah row deepens, Niluksi Koswanage, 2 January 2014, Reuters. Accessed on line 15 January 2014. Archived 16 January 2014 at the Wayback Machine

- Idris Jala (24 February 2014). "The 'Allah'/Bible issue, 10-point solution is key to managing the polarity". The Star. Retrieved 25 June 2014.

- D.B. Macdonald. Encyclopedia of Islam, 2nd ed, Brill. "Ilah", Vol. 3, p. 1093.

- Gerhard Böwering. Encyclopedia of the Quran, Brill, 2002. Vol. 2, p. 318

- Columbia Encyclopaedia says: Derived from an old Semitic root referring to the Divine and used in the Canaanite El, the Mesopotamian ilu, and the biblical Elohim and Eloah, the word Allah is used by all Arabic-speaking Muslims, Christians, Jews, and other monotheists.

- The Comprehensive Aramaic Lexicon – Entry for ʼlh Archived 18 October 2013 at the Wayback Machine

- Hitti, Philip Khouri (1970). History of the Arabs. Palgrave Macmillan. pp. 100–101.

- L. Gardet, Allah, Encyclopaedia of Islam, ed. by Sir H.A.R. Gibb

- Zeki Saritopak, Allah, The Qu'ran: An Encyclopedia, ed. by Oliver Leaman, p. 34

- Gerhard Böwering, God and his Attributes, Encyclopedia of the Qur'an, ed. by Jane Dammen McAuliffe

- Jonathan Porter Berkey (2003). The Formation of Islam: Religion and Society in the Near East, 600-1800. Cambridge University Press. p. 42. ISBN 978-0-521-58813-3.

- Daniel C. Peterson (26 February 2007). Muhammad, Prophet of God. Wm. B. Eerdmans Publishing. p. 21. ISBN 978-0-8028-0754-0.

- Francis E. Peters (1994). Muhammad and the Origins of Islam. SUNY Press. p. 107. ISBN 978-0-7914-1875-8.

- Irving M. Zeitlin (19 March 2007). The Historical Muhammad. Polity. p. 33. ISBN 978-0-7456-3999-4.

- "Allah." In The Oxford Dictionary of Islam. Ed. John L. Esposito. Oxford Islamic Studies Online. 1 January 2019. <http://www.oxfordislamicstudies.com/article/opr/t125/e128>.

- Lewis, Bernard; Holt, P. M.; Holt, Peter R.; Lambton, Ann Katherine Swynford (1977). The Cambridge history of Islam. Cambridge, Eng: University Press. p. 32. ISBN 978-0-521-29135-4.

- Thomas E. Burman, Religious Polemic and the Intellectual History of the Mozarabs, Brill, 1994, p. 103

- Marshall G. S. Hodgson, The Venture of Islam: Conscience and History in a World Civilization, University of Chicago Press, p. 156

- James Bellamy, "Two Pre-Islamic Arabic Inscriptions Revised: Jabal Ramm and Umm al-Jimal", Journal of the American Oriental Society, 108/3 (1988) pp. 372–378 (translation of the inscription) "This was set up by colleagues/friends of ʿUlayh, the son of ʿUbaydah, secretary/adviser of the cohort Augusta Secunda Philadelphiana; may he go mad/crazy who effaces it."

- Enno Littmann, Arabic Inscriptions (Leiden, 1949)

- Daniels, Peter T. (2014). The Type and Spread of Arabic Script.

- "The Himyarite Martyrs".

- James of Edessa the hymns of Severus of Antioch and others." Ernest Walter Brooks (ed.), Patrologia Orientalis VII.5 (1911)., vol: 2, p. 613. pp. ܐܠܗܐ (Elaha).

- Ignatius Ya`qub III, The Arab Himyarite Martyrs in the Syriac Documents (1966), Pages: 9-65-66-89

- Alfred Guillaume& Muhammad Ibn Ishaq, (2002 [1955]). The Life of Muhammad: A Translation of Isḥāq's Sīrat Rasūl Allāh with Introduction and Notes. Karachi and New York: Oxford University Press, page 18.

- M. A. Kugener, "Nouvelle Note Sur L'Inscription Trilingue De Zébed", Rivista Degli Studi Orientali, pp. 577-586.

- Adolf Grohmann, Arabische Paläographie II: Das Schriftwesen und die Lapidarschrift (1971), Wien: Hermann Böhlaus Nochfolger, Page: 6-8

- Beatrice Gruendler, The Development of the Arabic Scripts: From the Nabatean Era to the First Islamic Century according to Dated Texts (1993), Atlanta: Scholars Press, Page:

- Frederick Winnett V, Allah before Islam-The Moslem World (1938), Pages: 239–248

- Sidney H Griffith, "The Gospel in Arabic: An Enquiry into Its Appearance in the First Abbasid Century", Oriens Christianus, Volume 69, p. 166. "All one can say about the possibility of a pre-Islamic, Christian version of the Gospel in Arabic is that no sure sign of its actual existence has yet emerged.

- Grafton, David D (2014). The identity and witness of Arab pre-Islamic Arab Christianity: The Arabic language and the Bible.

Christianity [...] did not penetrate into the lives of the Arabs primarily because the monks did not translate the Bible into the vernacular and inculcate Arab culture with biblical values and tradition. Trimingham's argument serves as an example of the Western Protestant assumptions outlined in the introduction of this article. It is clear that the earliest Arabic biblical texts can only be dated to the 9th century at the earliest, that is after the coming of Islam.

- Sidney H. Griffith, The Bible in Arabic: The Scriptures of the 'People of the Book' in the Language of Islam. Jews, Christians and Muslims from the Ancient to the Modern World, Princeton University Press, 2013, pp242- 247 ff.

- The Arabic Bible before Islam – Clare Wilde on Sidney H. Griffith's The Bible in Arabic. June 2014.

- Hjälm, ML (2017). Senses of Scripture, Treasures of Tradition: The Bible in Arabic Among Jews, Christians and Muslims. Brill. ISBN 9789004347168.

- Hjälm, ML (2017). Senses of Scripture, Treasures of Tradition, The Bible in Arabic among Jews, Christians and Muslims (Biblia Arabica) (English and Arabic ed.). Brill. ISBN 978-9004347168.

By contrast, manuscripts containing translations of the gospels are encountered no earlier then the year 873 (Ms. Sinai. N.F. parch. 14 & 16)

- Irfan Shahîd, Byzantium and the Arabs in the Fourth Century, Dumbarton Oaks Trustees for Harvard University-Washington DC, page 418.

- Irfan Shahîd, Byzantium and the Arabs in the Fourth Century, Dumbarton Oaks Trustees for Harvard University-Washington DC, Page: 452

- A. Amin and A. Harun, Sharh Diwan Al-Hamasa (Cairo, 1951), Vol. 1, Pages: 478-480

- Al-Marzubani, Mu'jam Ash-Shu'araa, Page: 302

- Andreas Görke and Johanna Pink Tafsir and Islamic Intellectual History Exploring the Boundaries of a Genre Oxford University Press in association with The Institute of Ismaili Studies London ISBN 978-0-19-870206-1 p. 478

- Böwering, Gerhard, God and His Attributes, Encyclopaedia of the Qurʼān, Brill, 2007.

- Arabic script in Unicode symbol for a Quran verse, U+06DD, page 3, Proposal for additional Unicode characters

- Sale, G AlKoran

- Bentley, David (September 1999). The 99 Beautiful Names for God for All the People of the Book. William Carey Library. ISBN 978-0-87808-299-5.

- Murata, Sachiko (1992). The Tao of Islam : a sourcebook on gender relationships in Islamic thought. Albany NY USA: SUNY. ISBN 978-0-7914-0914-5.

- Gary S. Gregg, The Middle East: A Cultural Psychology, Oxford University Press, p.30

- Carolyn Fluehr-Lobban, Islamic Society in Practice, University Press of Florida, p. 24

- M. Mukarram Ahmed, Muzaffar Husain Syed, Encyclopaedia of Islam, Anmol Publications PVT. LTD, p. 144

- Carl W. Ernst, Bruce B. Lawrence, Sufi Martyrs of Love: The Chishti Order in South Asia and Beyond, Macmillan, p. 29

- F.E. Peters, Islam, p.4, Princeton University Press, 2003

- "How do you pronounce "Allah" (الله) correctly?". ARABIC for NERDS. 16 June 2018. Archived from the original on 17 June 2018. Retrieved 16 June 2018.

- William Montgomery Watt, Islam and Christianity today: A Contribution to Dialogue, Routledge, 1983, p.45

- Islam in Luce López Baralt, Spanish Literature: From the Middle Ages to the Present, Brill, 1992, p.25

- F. E. Peters, The Monotheists: Jews, Christians, and Muslims in Conflict and Competition, Princeton University Press, p.12

- Nation of Islam – personification of Allah as Detroit peddler W D Fard Archived 13 August 2013 at the Wayback Machine

- "A history of Clarence 13X and the Five Percenters, referring to Clarence Smith as Allah". Finalcall.com. Archived from the original on 22 October 2013. Retrieved 14 January 2014.

- Example: Usage of the word "Allah" from Matthew 22:32 in Indonesian bible versions (parallel view) as old as 1733 Archived 19 October 2013 at the Wayback Machine

- The Indonesian Language: Its History and Role in Modern Society Sneddon, James M.; University of New South Wales Press; 2004

- The History of Christianity in India from the Commencement of the Christian Era: Hough, James; Adamant Media Corporation; 2001

- Wiltens, Caspar; Heurnius, Justus (1650). Justus Heurnius, Albert Ruyl, Caspar Wiltens. "Vocabularium ofte Woordenboeck nae ordre van den alphabeth, in 't Duytsch en Maleys". 1650:65. Archived from the original on 22 October 2013. Retrieved 14 January 2014.

-

But compare:

Milkias, Paulos (2011). "Ge'ez Literature (Religious)". Ethiopia. Africa in Focus. Santa Barbara, California: ABC-CLIO. p. 299. ISBN 9781598842579. Retrieved 15 February 2018.

Monasticism played a key role in the Ethiopian literary movement. The Bible was translated during the time of the Nine Saints in the early sixth century [...].

- Barton, John (2002–12). The Biblical World, Oxford, UK: Routledge. ISBN 978-0-415-27574-3.

- North, Eric McCoy; Eugene Albert Nida ((2nd Edition) 1972). The Book of a Thousand Tongues, London: United Bible Societies.

- (in Indonesian) Biography of Ruyl

- "Encyclopædia Britannica: Albert Cornelius Ruyl". Britannica.com. Archived from the original on 19 October 2013. Retrieved 14 January 2014.

- Roughneen, Simon (14 October 2013). "No more 'Allah' for Christians, Malaysian court says". The Christian Science Monitor. Retrieved 14 October 2013.

- "BBC News - More than 300 Bibles are confiscated in Malaysia". BBC. 2 January 2014. Archived from the original on 25 January 2014. Retrieved 14 January 2014.

- "Catholic priest should respect court: Mahathir". Daily Express. 9 January 2014. Archived from the original on 10 January 2014. Retrieved 10 January 2014.

- Jane Moh; Peter Sibon (29 March 2014). "Worship without hindrance". The Borneo Post. Archived from the original on 29 March 2014. Retrieved 29 March 2014.

- "Bahasa Malaysia Bibles: The Cabinet's 10-point solution". 25 January 2014.

- "Najib: 10-point resolution on Allah issue subject to Federal, state laws". The Star. 24 January 2014. Retrieved 25 June 2014.

- "Zebed Inscription: A Pre-Islamic Trilingual Inscription in Greek, Syriac & Arabic From 512 CE". Islamic Awareness. 17 March 2005. Archived from the original on 13 October 2013.

-

- Arabic fonts and Mac OS X Archived 10 March 2008 at the Wayback Machine

- Programs for Arabic in Mac OS X Archived 6 October 2013 at the Wayback Machine

- The Unicode Consortium. FAQ - Middle East Scripts Archived 1 October 2013 at the Wayback Machine

- "Unicode Standard 5.0, p.479, 492" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 28 April 2014. Retrieved 14 January 2014.

References

- The Unicode Consortium, Unicode Standard 5.0, Addison-Wesley, 2006, ISBN 978-0-321-48091-0, About the Unicode Standard Version 5.0 Book

External links

| Wikisource has original text related to this article: |

| Wikiquote has quotations related to: Allah |

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Allah in calligraphy. |

- Names of Allah with Meaning on Website, Flash, and Mobile Phone Software

- Concept of God (Allah) in Islam

- The Concept of Allāh According to the Qur'an by Abdul Mannan Omar

- Allah, the Unique Name of God

- Typography