Audi Field

Audi Field is a soccer-specific stadium in Buzzard Point in Washington, D.C. It is the home stadium for the Major League Soccer team D.C. United. The stadium is also used by the Washington Spirit of the NWSL in select matches. The stadium seats 20,000 people.

Audi Field on July 25, 2018 | |

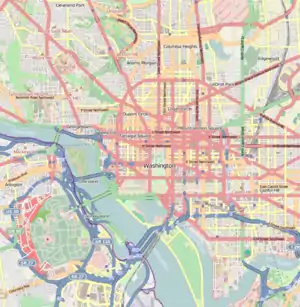

Audi Field Location in Washington, D.C.  Audi Field Location in the United States | |

| Address | 100 Potomac Avenue SW |

|---|---|

| Location | Washington, D.C. |

| Coordinates | 38°52′6″N 77°0′44″W |

| Public transit | |

| Owner | District of Columbia |

| Operator | D.C. United |

| Capacity | 20,000 |

| Field size | 115 yd × 75 yd (105 m × 69 m) |

| Surface | NorthBridge™ Bermuda |

| Construction | |

| Broke ground | February 27, 2017[1] |

| Opened | July 9, 2018 (ribbon cutting)[2] July 14, 2018 (first game)[3] |

| Construction cost | $400 million – $500 million |

| Architect | Populous[4] Marshall Moya Design[5] |

| General contractor | Turner Construction Company |

| Tenants | |

| D.C. United (MLS) (2018–present) Washington Spirit (NWSL) (2019–present) DC Defenders (XFL) (2020) Loudoun United (USLC) (2019) | |

| Website | |

| www | |

Previously, D.C. United had explored sites in the Washington metropolitan area. Following the failure of an initial stadium proposal in 2006, D.C. United made two additional stadium proposals that also failed to be built.

In January 2011, the club explored using previously-unused land at Buzzard Point to build a stadium; this was confirmed in July 2013, when Buzzard Point was announced as the stadium location.[6] The ground-breaking ceremony occurred in February 2017, with construction completed in July 2018.

Site selection

Early proposals

D.C. United and Major League Soccer commissioner Don Garber raised concerns about scheduling conflicts with the Washington Nationals at RFK Stadium in July 2004, with Garber stating that a soccer-specific stadium in Washington, D.C. "needs to become a priority".[7] Later that year, D.C. United unveiled a proposal to build a 24,000-seat stadium at Poplar Point along the Anacostia River, to open in time for the 2007 season.[8] The stadium's size was later increased to 27,000 and incorporated into a mixed-use development on the site to the revitalize the Anacostia neighborhood, with the support of Ward 8 councilmember Marion Barry after he initially opposed the stadium.[9][10]

The stadium project was neglected by the city's leadership during the debate over a baseball stadium in Navy Yard.[11] After a change of ownership for D.C. United in January 2007, the $200 million stadium project was moved into public review, where it drew criticism over its public financing, gentrification, and displacement of residents.[12][13] By mid-July, the Poplar Point plan was abandoned and D.C. United began looking at other locations for the stadium.[14]

Despite the failed bid, then-Mayor Adrian Fenty opted to have a closed-door meeting in February 2008 to discuss the city funding $150 million for the club.[15] However, despite a short-lived renewed interest, when the D.C. Council recessed in July 2008, the plan never was brought up, and ultimately died after the main developer for the Poplar Point project withdrew their funding.[16]

In February 2009, the team announced plans for a new stadium in nearby Prince George's County, Maryland, close to FedExField. This proposal ran into similar trouble, however, when the Prince George's County Council voted to send a letter to the Maryland General Assembly opposing the stadium plan.[17]

Poplar Point

Originally, D.C. United proposed building a stadium at Poplar Point on the Anacostia riverfront in Washington, D.C. as part of a planned 110-acre (0.45 km2) mixed-use development that would have included a hotel, offices, housing, and retail.[18] Plans were formulated as early as 2005 and were formally announced in January 2007.[19]

However, in July 2007, the talks stalled between the team and city officials. There were disputes over the financial arrangements proposed by the team, which would have the city providing $200 million in subsidies and development rights while the team assumed construction costs.[20] In January 2008, the team announced it was looking at other possible sites in the area for construction of the new stadium.[21]

In February 2008, Washington, D.C., mayor Adrian Fenty suggested at a closed-door city council meeting that the city might offer as much as $150 million towards the costs of building a soccer stadium at Poplar Point. There was apparently renewed interest on the part of the city in providing public funds for the stadium at Poplar Point.[22] However, in July 2008, the D.C. Council recessed without considering the proposed stadium plan.

With sites in Maryland entering the discussion,[23] negotiations continued throughout 2008 before collapsing in early 2009 as the developer pulled out of the project.[24]

Prince George's County

Maryland first expressed an interest in United as talks stalled in summer 2007. In February 2009, United co-owner Victor MacFarlane announced the team would seek a new stadium in Prince George's County.[25]

However, county officials began expressing concerns about revenue from the stadium in March, and on April 7, the Prince George's County Council voted to outline its concern to the Maryland General Assembly about a proposed state legislation that would authorize a feasibility study for the new stadium. The legislation stalled in the Statehouse and died without the support of the Prince George's Council.[26]

Following the failure of the Prince George's County proposal, United began surveying fans about the possibility of relocating to Loudoun County, Virginia; Frederick County, Virginia; or Montgomery County, Maryland.[27] However, no public negotiations ever began.

Baltimore

In October 2009, Baltimore mayor Sheila Dixon asked the Maryland Stadium Authority to explore building a soccer stadium to serve as D.C. United's home, as well as to host concerts, lacrosse games, and other events. A potential location mentioned for the stadium was the 42-acre (170,000 m2) Westport Waterfront project, and the proposed stadium would have had access to light rail and Interstates 95 and 295.[28]

Meanwhile, in March 2010, MLS commissioner Don Garber criticized Washington, D.C., politicians for how long it had taken to find D.C. United a permanent home stadium.[29]

Discussions continued with Baltimore and other sites in Maryland, with a feasibility study released in December 2010.[30] However, the club opted to refocus its efforts on finding a location within the District of Columbia.

Loudoun County

In May 2015, team officials visited potential sites in Loudoun County, Virginia, and met with county and state officials about building a stadium in Northern Virginia rather than Washington. Virginia Governor Terry McAuliffe's economic development team suggested sites in Woodbridge, Virginia, and Loudoun, while Loudoun County officials had multiple meetings with team officials. In a letter to the team, Loudoun economic development director Buddy Rizer wrote that a stadium in Virginia would be $38 million cheaper than in D.C. and would be ready by the 2017 season, which the team claimed was not possible in Washington.[31]

Buzzard Point

In January 2011, the Web site Greater Greater Washington reported that the club was looking into building a stadium in the Buzzard Point neighborhood in the city.[32] The project involved land owned by the Akridge Development Co. only a few blocks from Nationals Park.[33] By May, according to the Washington Post, the team was also considering a stadium at a site near the Capital City Market[34] and the Westport neighborhood of Baltimore.[35]

In late May 2012, D.C. United was sold to a group led by Indonesian businessman Erick Thohir and attorney Jason Levien, with former principal owner William Chang remaining as a minority partner. The new owners said Buzzard Point remained their preferred option for a new stadium site.[35] A few days after the sale was announced, the Washington Post obtained a confidential draft report, commissioned by the Greater Washington Sports Alliance (a private, nonprofit foundation), which said a 24,000-seat stadium would cost $157 million to build (which did not include the price of land). Construction of the stadium could generate $19.5 million in wages and $38 million in spending, and the completed stadium would likely employ 600 to 800 part- and full-time jobs and generate $5.5 million to $7.3 million a year in tax revenue. The study assumed the stadium would include an $82 million mixed-use development as well.[36]

Financing and construction

On July 25, 2013, the District of Columbia and D.C. United announced a tentative deal to build a $300 million, 20,000–25,000-seat stadium at Buzzard Point.[37][38] The deal required the District of Columbia to obtain the Akridge land at Buzzard Point in exchange for cash and title to the Frank D. Reeves Municipal Center (the city's primary government office building, located in the desirable Shaw neighborhood). D.C. United would contribute $150 million to construct the stadium on the city-owned land, which it would lease for 20 to 35 years. The deal also gave D.C. United the right to build restaurants, bars, and even a hotel nearby.[39] The Buzzard Point plan—formally termed the District of Columbia Soccer Stadium Act of 2014—was approved by the D.C. City Council on December 17, 2014.[40]

The December legislation significantly revised the July 2013 agreement. No longer would the city give Akridge a building and cash; now the city would pay fair market value for the Akridge land. If a deal could not be reached through negotiation, the legislation gave the city the right to use eminent domain to seize the land.[41] In another revision, the city agreed to contribute the $150 million to purchase land for the stadium. $89 million of this amount was for land acquisition, while another $61 million would be to improve utilities, remove toxic and hazardous wastes, and clear the land for construction. D.C. United also agreed to spend at least $150 million for stadium construction.[42] The legislation did not provide the club with $7 million in sales tax breaks it sought, but did give it $43 million in property tax credits.[43] Outgoing Mayor Vincent Gray signed the bill into law on December 30, as one of the final acts of his term.[44]

Negotiations between the city and Akridge began in January 2015. D.C. Council Chairman Phil Mendelson was downbeat about the talks, saying the two sides were "very far apart" on a price.[41] In February, club officials estimated that the stadium would take 14 to 16 months to construct.[45] Mayor Muriel Bowser, Gray's successor, budgeted $106.3 million in fiscal 2016 to acquire the stadium site, add infrastructure (such as water, sewer, electrical, and natural gas lines), and remove toxic hazards at the site.[46] The budget provided for borrowing $106 million and reprogramming $32 million away from the city's school modernization program to pay for the city's stadium costs.[43] The D.C. City Council began working on legislation to permanently close several city streets that crossed the stadium land in April 2015.[42]

As the city and club came close to finalizing its lease agreement in May, D.C. United began talking with city, county, and state officials in Virginia about abandoning the District of Columbia and constructing a stadium in Northern Virginia. The talks became public knowledge on June 1. D.C. officials were outraged, although they conceded the initiative was probably just a negotiating tactic to get the city to sweeten its deal.[47] The controversy did not appear to harm the talks, as on June 8, D.C. United and the city signed a final construction agreement. The agreement required that the facility seat a minimum of 17,000 people, and established the term of the lease at 30 years for a minimal $1 per year. The agreement also contained a clause governing land: If the cost of land acquisition rose above $150 million, D.C. United was required to reimburse the city 50% of the excess (although the club's commitment was capped at $10 million). The club was also barred from playing more than an occasional home game away from the Buzzard Point stadium (i.e., barred from relocating for the term of the lease).[48] Mayor Bowser then submitted the agreement, as well as land purchase agreements and a revised developer agreement, to the City Council for approval. The land purchase agreements paid Pepco $39.3 million for land and $1 million to remove electrical generation equipment from its site, $15.9 million for land owned by Super Salvage, and $10.32 million for land owned by developer Mark Ein (owner of the Washington Kastles professional tennis team). The cost of the land purchase agreements was offset by a deal for Pepco to purchase a $15 million city-owned parcel of land at 1st and K Streets NW. The council approved the land purchase agreements on June 30, 2015.[42]

Under the terms of the June 8 agreement, D.C. United was required to submit a concept design for the stadium to the city by September 1, 2015. The District of Columbia faced a deadline of September 30, 2015, to use eminent domain to acquire the Akridge land, which forced the club to commit to building a stadium before the city finished purchasing land.[43] On September 30, the District of Columbia filed for eminent domain for the Akridge parcel.[49]

On February 15, 2017, German automobile manufacturer Audi and D.C. United announced a "long-term" naming rights deal for the new stadium.[50] The Washington Post reported the deal was for a minimum of twelve years.[50] Audi's United States headquarters are located in Herndon, Virginia, a suburb of Washington.[50] Construction began two weeks later with a ceremonial groundbreaking.[1]

Opening

Audi Field had a ribbon-cutting ceremony on July 9, 2018. The first-ever opening match held in Audi Field was a Major League Soccer match between D.C. United and Vancouver Whitecaps FC on July 14, 2018, which ended in a 3–1 win for D.C. United in front of a sellout crowd of 20,504 people.[51] A sideline reporter was injured after being hit by a piece of the railing.[52]

Public transport

Audi Field is within 1 mile (1.6 km) of the Navy Yard–Ballpark station of the Washington Metro. The station is served by the Green Line. It is also served by DC Circulator and Potomac Riverboat Company shuttle services on match days.[53]

Sports

Soccer

In addition to serving as the home stadium for D.C. United, Audi Field occasionally hosts other soccer matches. On August 25, 2018, in a National Women's Soccer League regular season match, the hometown Washington Spirit lost 1–0 to the visiting Portland Thorns FC.[54] The Spirit returned to Audi Field for two matches in the 2019 season, against the Orlando Pride on August 24 and Reign FC on September 14.[55] The Spirit are now transitioning toward making Audi Field their primary home venue. In 2020, they were slated to play four home games at each of three venues—Audi Field; their original home of the Maryland SoccerPlex in Montgomery County; and Segra Field, home of D.C. United's USL Championship reserve side Loudoun United FC in Leesburg, Virginia. In 2021, the Spirit will play seven home games at Audi Field and five at Segra Field.[56]

On September 3, 2018, the Maryland Terrapins men's soccer and Virginia Cavaliers men's soccer teams drew 0–0 in the first collegiate soccer match played at Audi Field.[57]

Loudoun United used Audi Field for three home games in their inaugural 2019 season while its permanent venue of Segra Field was under construction.[58]

The United States men's national soccer team played an international friendly match against Jamaica at Audi Field on June 5, 2019.[59] The US lost 1–0.[60] The USMNT played at Audi Field again in a CONCACAF Nations League game against Cuba on October 11, 2019. The US won 7–0.[61]

Lacrosse

In its inaugural season, the Premier Lacrosse League played three games at Audi Field the weekend of July 6–7, 2019.[62]

Football

In 2020, the DC Defenders of the XFL played their home games at Audi Field.[63] Their first game was on February 8, 2020, with the Defenders defeating the Seattle Dragons by a score of 31–19.[64] After three home games, the XFL season was suspended and ultimately canceled due to the COVID-19 pandemic. The Defenders won all three games at Audi Field.

See also

References

- Rodriguez, Alicia (February 16, 2017). "DC United announce stadium groundbreaking ceremony on February 27". MLSsoccer.com. Retrieved February 17, 2017.

- Giambalvo, Emily (July 10, 2018). "D.C. United ushers in 'a new era' with Audi Field ribbon-cutting ceremony". Washington Post. Retrieved July 10, 2018 – via www.WashingtonPost.com.

- Goff, Steven (January 4, 2018). "D.C. United will open Audi Field on July 14, setting up All-Star Week on waterfront". Retrieved January 5, 2018 – via www.WashingtonPost.com.

- Bromley, Ben (February 15, 2014). "New D.C. United Stadium Renderings, by Architecture Firm Populous, Released". SB Nation. Retrieved June 3, 2014.

- Hansen, Drew (April 21, 2016). "D.C. United Stadium Has a Name (at Least Tentatively)". Washington Business Journal. Retrieved June 3, 2016.

- Boehm, Charles (July 25, 2013). "D.C. United Announce Long-Awaited Plans for New Stadium in Buzzard Point". Major League Soccer. Retrieved July 25, 2013.

- Goff, Steven (July 30, 2004). "United Seeks Stadium Solution". The Washington Post. p. D1. Retrieved February 17, 2017.

- Goff, Steven (October 1, 2004). "Details Given on United's Proposed Stadium". The Washington Post. p. D5. Retrieved February 17, 2017.

- Pierre, Robert E. (December 12, 2005). "It's All About the Pitch for United". The Washington Post. p. B1. Retrieved February 17, 2017.

- Pierre, Robert E. (November 16, 2005). "Barry Now Backs Soccer Stadium, Sees Help for Ward". The Washington Post. p. B8. Retrieved February 17, 2017.

- Nakamura, David; Goff, Steven (December 22, 2006). "Soccer Stadium by 2009? City and D.C. United Differ". The Washington Post. p. B4. Retrieved February 17, 2017.

- "D.C. United under new leadership". USA Today. Associated Press. January 9, 2007. Retrieved February 17, 2017.

- Nakamura, David (January 21, 2007). "In Ward 8, Residents Voice Skepticism of Poplar Point Plan". The Washington Post. p. C1. Retrieved February 17, 2017.

- Nakamura, David (July 21, 2007). "Talks Fall Apart on Stadium for D.C. Soccer Team". The Washington Post. p. A1. Retrieved September 6, 2009.

- Nakamura, David (May 28, 2008). "D.C. Council Crafting Plan to Pay $150 Million for Soccer Stadium". The Washington Post. p. A1. Retrieved February 17, 2017.

- Nakamura, David (January 31, 2009). "Poplar Point Developer Pulls Out Of Project". The Washington Post. p. B1. Retrieved February 17, 2017.

- Castro, Melissa (April 7, 2009). "Prince George's vote likely kills D.C. United stadium deal". Washington Business Journal.

- Drobnyk, Josh (July 14, 2006). "D.C. Land Swap Could Get Kicked to the Curb in '06". Washington Business Journal. Retrieved July 17, 2006.

- Goff, Steven (July 29, 2005). "Local Group Pays $26 Million for United". The Washington Post. Retrieved March 2, 2014.

- Nakamura, David (July 21, 2007). "Talks Fall Apart On Stadium for D.C. Soccer Team". The Washington Post. p. A01. Retrieved March 2, 2014.

- Wiggins, Ovetta (January 23, 2008). "Md. Weighs Stadium for D.C. United; Study Will Gauge Pr. George's Benefits". The Washington Post. p. B01. Retrieved March 2, 2014.

- Nakamura, David (February 14, 2008). "Fenty Eyes Public Funds for Soccer Stadium". The Washington Post. p. A01. Retrieved March 2, 2014.

- Nakamura, David (October 17, 2007). "Md. Comes Courting in D.C. United's Stadium Search". The Washington Post. Retrieved March 2, 2014.

- Nakamura, David (January 31, 2009). "Poplar Point Developer Pulls Out Of Project". The Washington Post. Retrieved March 2, 2014.

- Helderman, Rosalind; Nakamura, David (February 13, 2009). "P.G. United?". The Washington Post. p. B01. Retrieved March 2, 2014.

- Castro, Melissa (April 7, 2009). "Prince George's Vote Likely Kills D.C. United Stadium Deal". Washington Business Journal. Retrieved March 2, 2014.

- Kravitz, Derek (June 18, 2009). "D.C. United Seeks Fan Input in Search for New Home". The Washington Post. Retrieved March 2, 2014.

- Van Valkenburg, Kevin; Mirabella, Lorraine (October 7, 2009). "Dixon Eyeing Soccer Arena". The Baltimore Sun. Retrieved October 22, 2009.

- Blum, Ronald (March 23, 2010). "Garber Criticizes DC for Lack of Soccer Stadium". USA Today. Retrieved March 2, 2014.

- O'Connell, Jonathan (December 23, 2010). "D.C. United to Baltimore = revenue". The Washington Post. Retrieved May 28, 2011.

- O'Connell, Jonathan (June 2, 2014). "At 11th hour, D.C. United considers bolting for Virginia". Washington Post. Retrieved June 2, 2014.

- Weber, Erik (January 19, 2011). "DC United Eyeing Buzzard Point, Florida Market". Greater Greater Washington. Retrieved October 19, 2011.

- Sherwood, Tom (January 17, 2011). "D.C. United's New Home Could Be in SW". NBC Washington. Retrieved October 19, 2011.

- Goff, Steven; O'Connell, Jonathan (May 12, 2011). "Struggling with Crumbling RFK Stadium, D.C. United Is Desperate for a New Home". The Washington Post. Retrieved May 28, 2011.

- Goff, Steven (May 31, 2012). "D.C. United Investment and Stadium Update: Will Chang Says He Would Retain Stake in MLS club". The Washington Post. Retrieved March 2, 2014.

- O'Connell, Jonathan (June 3, 2012). "Capital Business". The Washington Post. Retrieved July 1, 2015.

- "Deal reached for new stadium". StadiaDirectory. July 25, 2013. Archived from the original on September 27, 2013. Retrieved July 25, 2013.

- "Term Sheet DC United Stadium Project" (PDF). District of Columbia and DC Soccer LLC. District of Columbia Office of the City Administrator. July 25, 2013. Archived from the original (PDF) on March 4, 2016.

- O'Connell, Jonathan (July 24, 2013). "Mayor Gray, D.C. United reach tentative deal on soccer stadium for Buzzard Point". The Washington Post. Retrieved April 13, 2015.

- Goff, Steven (December 2, 2014). "D.C. United's stadium wait is almost over". The Washington Post. Retrieved December 3, 2014; "Mayor Gray signs bill to fund DC United soccer stadium". WUSA-9. December 30, 2014. Archived from the original on April 2, 2015. Retrieved March 7, 2015.

- Neibauer, Michael (January 5, 2015). "D.C., Akridge 'very far apart' on D.C. United stadium land price". Washington Business Journal. Retrieved April 13, 2015.

- Neibauer, Michael (June 30, 2015). "D.C. United stadium takes a key step forward". Washington Business Journal. Retrieved July 1, 2015.

- Heller, Chris (June 26, 2015). "A Safe Bet?". Washington City Paper. Retrieved July 1, 2015.

- "Mayor Gray signs bill to fund DC United soccer stadium". WUSA 9. December 30, 2014. Archived from the original on April 2, 2015. Retrieved March 7, 2015.

- Goff, Steven (February 19, 2015). "D.C. United's Buzzard Point stadium plans taking shape behind the scenes". The Washington Post. Retrieved July 1, 2015.

- Neibauer, Michael (April 7, 2015). "New building, new debt and crazy housing prices: A dive into D.C.'s 2016 budget proposal". Washington Business Journal. Retrieved April 13, 2015.

- O'Connell, Jonathan; Davis, Aaron C. (June 2, 2015). "Bowser: District has 'very generous deal' on table for United stadium". The Washington Post. Retrieved July 1, 2015.

- O'Connell, Jonathan (June 9, 2015). "United, District reach final terms on stadium deal". The Washington Post. Retrieved July 1, 2015; Straus, Brian (June 8, 2015). "D.C. United reaches development deal with city for anticipated new stadium". Sports Illustrated. Retrieved July 1, 2015.

- "Akridge Eminent Domain (9-30-2015) – dmped". dmped.dc.gov. Retrieved October 26, 2017.

- Goff, Steven. "D.C. United strikes deal with Audi for stadium naming rights". The Washington Post. February 15, 2017.

- Giambalvo, Emily (July 14, 2018). "D.C. United debuts Audi Field, and Wayne Rooney, in a convincing win over Vancouver". The Washington Post. Retrieved July 14, 2018.

- Reineking, Jim (July 14, 2018). "Sideline reporter hit with falling debris in D.C. United's first game at Audi Field". USA Today. Retrieved July 14, 2018.

- "Transportation to Audi Field". DC United. July 24, 2018. Retrieved July 29, 2018.

- Goff, Steven (August 25, 2018). "NWSL's Spirit falls to Portland in debut at Audi Field". The Washington Post. Retrieved April 12, 2019.

- Goff, Steven (April 4, 2019). "Washington Spirit set to play a pair of matches at Audi Field". The Washington Post. Retrieved April 12, 2019.

- Levine, Matthew (November 18, 2019). "Washington Spirit to split home games between Audi Field, Segra Field, and Maryland SoccerPlex in 2020". National Women's Soccer League. Retrieved November 19, 2019.

- Goff, Steven (September 3, 2018). "Maryland, Virginia men take their rivalry to Audi Field, settle for scoreless draw". The Washington Post. Retrieved April 12, 2019.

- Augenstein, Neal (April 8, 2019). "Loudoun United will play some 'home' games at Audi Field". WTOP-FM. Retrieved April 12, 2019.

- Goff, Steven (April 24, 2019). "U.S. soccer team will make first visit to Audi Field for friendly vs. Jamaica". The Washington Post. Retrieved April 24, 2019.

- Ilyas, Adnan (June 6, 2019). "USA v. Jamaica, 2019 friendly: What we learned". Stars and Stripes FC. Retrieved June 6, 2019.

- "McKennie's Early Hat Trick Paces USA's Nations League Rout of Cuba". Sports Illustrated. October 11, 2019. Retrieved October 11, 2019.

- Bogage, Jacob (March 22, 2019). "New Premier Lacrosse League will visit Audi Field in July". The Washington Post. Retrieved April 12, 2019.

- "XFL coming to Audi Field in 2020". DC United. December 5, 2018. Retrieved April 12, 2019.

- "Seattle Dragons can't keep up with DC Defenders in season-opening loss on XFL's inaugural weekend". The Seattle Times. February 8, 2020. Retrieved February 9, 2020.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Audi Field. |

- Official website

- Audi Field page on D.C. United website

| Preceded by RFK Stadium |

Home of D.C. United 2018 – present |

Succeeded by Current |