Austin Police Department

Austin Police Department (APD) is the principal law enforcement agency serving Austin, Texas. As of Fiscal Year 2018, the agency had an annual budget of more than $442 million and employed around 2,646 personnel, including approximately 1,900 officers.[3] Brian Manley was named chief of police[4] effective June 14th, 2018.[5]

| Austin Police Department | |

|---|---|

| |

| |

| Abbreviation | APD |

| Agency overview | |

| Employees | 2,422 (2020) |

| Annual budget | $376 million (2020)[1] |

| Jurisdictional structure | |

| Operations jurisdiction | Austin, Texas, USA |

| |

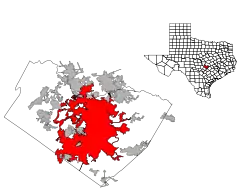

| Map of Austin Police Department's jurisdiction. | |

| Size | 296.2 square miles (767 km2) |

| Population | 964,243 (2018) |

| General nature | |

| Operational structure | |

| Headquarters | Austin, Texas |

| Officers | 1,851[2] |

| Civilian employees | 571 |

| Agency executive |

|

| Website | |

| Austin Police | |

Specialized units

- Aggravated Assault Unit

- Air Support Unit

- Auto Theft Interdiction Unit

- Chaplain

- Child Abuse Unit

- Cold Case Unit

- Commercial Vehicle Enforcement

- Counter Assault Strike Team (CAST)

- Court Services

- Decentralized Investigations

- Digital Forensics Unit

- DWI investigation and Enforcement Team

- Executive Protection Unit

- Explosive Ordnance Disposal (EOD)

- Family Violence Protection Team

- Financial Crimes Unit

- Gang Suppression Unit

- Homicide

- Honor Guard

- Homeless Outreach Street Team (HOST)

- Human Trafficking Unit

- Intelligence

- Internal Affairs (IA)

- K9 Unit

- Lake Patrol Unit

- Mounted Patrol Horse Unit

- Peer Support Unit

- Property Management

- Public Safety Unit (Airport, Parks, Downtown)

- Recruiting

- Risk Management Unit

- Robbery Unit

- Sex Crimes Unit

- Special Events Unit

- Special Investigations Unit (SI)

- Special Weapons & Tactics (SWAT)

- Traffic/ Highway Enforcement

- Training Academy

- Vehicular Homicide Unit

- Victim Services (VSU)

Patrol divisions

- Downtown Area Command

- Northeast Area Command

- Northwest Area Command

- North Central Area Command

- Central East Area Command

- Central West Area Command

- Southeast Area Command

- Southwest Area Command

- South Central Area Command

- Highway Enforcement Command (Motors, Commercial Vehicle Enforcement, DWI Enforcement)

Ranks

Fallen Officers

Since the establishment of the Austin Police Department, twenty-three officers have died in the line of duty.[6] The following list also contains one officer from the Austin Park Police Department, which was merged into APD.

| Officer | Date of death | Details |

|---|---|---|

| Officer Cornelius L. Fahey | Gunfire | |

| Officer John Gaines | Gunfire | |

| Officer Tom Allen | Gunfire | |

| Chief of Police James N. Littlepage | Gunfire | |

| Sergeant William Murray Stuart | Vehicle pursuit | |

| Officer James R. Cummings | Motorcycle accident | |

| Officer Elkins P. Morrison | Struck by vehicle | |

| Sergeant Walter Lee Tucker | Motorcycle accident | |

| Officer Donald Eugene Carpenter | Gunfire | |

| Officer Billy Paul Speed | Gunfire | |

| Officer Thomas Wayne Birtrong | Automobile accident | |

| Officer Leland Dale Anderson | Gunfire | |

| Officer Ralph Allen Ablanedo | Gunfire | |

| Officer Lee Craig Smith | Motorcycle accident | |

| Officer Robert Townes Martinez Jr. | Automobile accident | |

| Officer Drew A. Bolin | Vehicular assault | |

| Officer William DeWayne Jones Sr. | Gunfire | |

| Office Clinton Hunter | Vehicular assault | |

| Sergeant Earl Alison Hall | Heart attack | |

| Officer Amy Lynn Donovan | Struck by vehicle | |

| Senior Officer Jaime D. Padron | Gunfire | |

| Lieutenant Clay D. Crabb | Automobile crash | |

| Senior Officer Amir Abdul-Khaliq | Motorcycle crash |

Controversial Deaths* Related to Use of Force by APD Officers

*Cases were selected based on the NAACP Austin Branch's list of 1984-2020 questionable use of force deaths,[7] as well as cases that were the subject of significant protests, media coverage, disciplinary action, judiciary investigation, or cases in which officers were involved in other controversial deaths or incidents. Of note, from 1979 to 2016, all cases in which officers used deadly force (including all cases where police discharged a weapon) were automatically brought before a grand jury. As was the case before 1979, the Travis County District Attorney may choose whether or not to present to case to a grand jury based on their investigation.

| Victim | Date of Death | Involved Officer(s) | Details | Officer Outcome |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Joe Cedillo, Jr. | July 31, 1971 | James Johnson, Paul Looney | Police state they saw Cedillo fleeing from the site of a reported burglary. Johnson and Looney both fired at Cedillo when he kept fleeing, despite orders to halt. Cedillo was shot once in the back of the head.[8] Protestors gathered at city hall and within a city council meeting to protest the shooting and the alleged pattern of police brutality in East Austin.[9] Chief of Police R. A. Miles said that protesters were "playing into the hands of The Communists... by discrediting the police in the eyes of the public".[10] | Grand jury declined to indict.

No disciplinary action.[10] |

| Tiburcio Soto | October 6, 1974 | Ruben Fuentes, Joe Villegas | Police were responding to a domestic disturbance, where they report that Soto was in an argument with his son. Police said that Soto got ahold of Villegas' gun while officers were attempting to separate the father and son. Soto allegedly pointed the gun at Fuentes, who then shot Soto four times at close range. The shooting was controversial as witness testimony differed from police. Many witnesses said that Soto simply picked up Villegas' gun by the barrel after it was dropped and never pointed it at police.[11] The shooting prompted public outcry and inspired the creation of a Community Relations Task Force[12] | No disciplinary action.

Grand jury declined to indict.[12] |

| James Lyndon Park | January 29, 1976 | Ron Smith | Smith was on patrol when he saw Park robbing a clerk at a convenience store. According to the clerk, when Park saw the officer stop he told the clerk to come outside with him and tell the officer that nothing was wrong. When the two came outside, Smith drew his weapon and Park walked quickly away from the scene. Smith said that he thought he saw Park reaching for a weapon as he walked away, which is what led him to decide to shoot him. It was later revealed that Park was unarmed and shot in the back of the head. The case drew little attention at the time but became controversial later, when the same officer was involved in the 1984 suffocation of Evans Ekiye.[13] | No disciplinary action.

The assistant district attorney decided not to present the case to a grand jury.[13] |

| Gril Couch | August 1, 1979 | Dunny Donavan, Claude Hooker | Donavan and Hooker, two plain clothes officers, attempted to arrest Couch for public drunkenness after he lunged at them repeatedly in a barbeque restaurant where they were eating lunch. According to witnesses, one of the officers called for a uniformed officer to come arrest Couch after he lunged at them twice but decided to arrest him sooner on the restaurant staff's request. A struggle broke out during which, according to witnesses, one officer held Couch in a choke hold until he went limp and for at least 3-4 minutes after that. Couch was pronounced dead at the scene. His autopsy revealed a fractured larynx and listed asphyxiation as his cause of death.[14] The police later admitted that they never identified themselves to Couch as police officers.[15] The incident sparked outrage in the East Austin community, especially given Couch's history of mental illness, and led to six weeks of demonstrations as well as an FBI investigation. The incident also led to the enactment of a policy that all deaths caused by APD officers be brought before a grand jury.[16] | No disciplinary action. Grand jury declined to indict.[17] Both officers later quit the APD. Hooker cited loss of public support for officers and increasing complication of the job as his reasons for resigning.[18] |

| Vincent Trujillo | January 27, 1980 | Daniel Pena | Pena was called to a suspected break-in and saw Trujillo fleeing the scene. Pena told investigators that he fired his shotgun first when Trujillo turned toward him with a shiny object in his hand (which was later confirmed as a butcher knife) but the shot missed. The chase resumed but Pena then slipped while running, at which point his gun discharged accidentally and killed Trujillo.[19] | Grand jury declined to indict.[20] |

| Evans Ekiye | December 5, 1984 | Ron Smith, Randall Pasley, Joe Regalado, Amando Balderama | Police were sent to Nigerian student Evans Ekiye's address for a domestic disturbance call, where Ekiye's wife told police he had beaten her and threatened her with a gun. Ekiye allegedly attacked Smith when he was looking for the gun. A fight started between Ekiye and the four officers, which ended when the officers handcuffed him and held him face-down on a water bed.[21] Officers continued holding Ekiye face down up until medics called by the officers arrived at the scene. Eikye's cause of death was ruled as suffocation.[22] The case prompted the APD to add more training on detecting when they are injuring someone in police custody.[23] It also spurred an official complaint to the State Department by the Nigerian government, who visited Austin to investigate the case.[24] The case was heavily protested in Austin. Members of the local Black Citizens Task Force picketed in front of APD headquarters for an hour every day for 18 months.[25] | No disciplinary action.

A district grand jury declined to indict at the time.[21] The case was further investgated by the Texas Attorney General, who concluded that the officers could be prosecuted for criminally negligent homicide. However, the grand jury declined to reopen the case after review of the report.[26] |

| Arthur Martinez | October 30, 1990 | Tobias Santiago | Santiago and four other officers were called to a local park when residents reported hearing gunshots. The officers found a group of teenagers drinking and shooting at targets. The teens scattered when police announced themselves, except for Martinez who allegedly pointed the gun at Santiago. Martinez's blood alcohol level was 0.15, according to the medical examiner.[27] The family claimed that Martinez's wounds indicated that he was running away from officers when shot and that at least one of the teens present told them that Martinez was not holding a gun (though all teens later testified that he was armed). Critics also noted that the five teenagers were not interviewed by the grand jury until late in the investigation.[28] Santiago had twelve complaints on his record with APD, four of which he had been disciplined for including rudeness, verbal abuse, and retaliation.[29] | Grand jury declined to indict.[28] The family sued the City of Austin for wrongful death but the jury found in favor of the city.[29] |

| Rodney Wickware | Jan 24, 1998 | Alfred Trejo, four other unnamed officers | Trejo saw Wickware walking in and out of traffic. According to police, Wickware resisted arrest and required five officers to subdue him. He suddenly stopped breathing during fight. The county Medical Examiner reported that Wickware had two broken ribs and fractured larynx, which indicated he had been choked during the fight,[30] but ruled the cause of death as ethylene glycol poisoning,[31] presumably from self-ingestion. | Grand jury declined to indict.[31] |

| Johnny Cornell | Feb 2, 1999 | Stan Farris | Police were called after Cornell set fire to a car with his mother and her friend inside. Witnesses confirmed that Cornell walked toward Farris with a butcher knife, ignoring commands to stop, and was shot four times. The case was controversial because Cornell had a history of mental illness.[32] | Grand jury declined to indict.[32] |

| Albert Juarez | January 23, 1999 | Billie Hancock and Duane Williams | Police called for domestic abuse report. Witnesses confirmed that Juarez approached police concealing a box cutter in his pocket and refused orders to stop and show his hands. Police shot Juarez six times before he stopped advancing towards police[32] | Grand jury declined to indict.[32] |

| Herbert Vences | March 2, 1999 | Troy Brown and Ross Arnold | Police responded to report of man lunging into traffic. Officers found Vences in a nearby parking lot and tried to arrest him but he fled. Brown shot Vences after he allegedly "took a broken piece of [tree] limb and raised it like a spear over [Arnold's] face".[32] | Unknown |

| Erik McDonald | September 24, 1999 | Allen McClure, William Pursley and Jerry Sullivan | Police called for ongoing domestic assault. McDonald allegedly began fighting with police on arrival, requiring restraint. Witnesses reported seeing McDonald unconscious with blood running from his nose and mouth, though the medical examiner reported minimal injuries. Cause of death ruled as PCP overdose.[33] | Unknown.

Jerry Sullivan was later named in 2000 lawsuit for knocking Choyce Perkins to the ground with a flashlight for allegedly interfering with her son's arrest (who was apparently seizing), though witnesses say she was 20 feet away.[34] Allen McClure was later criticized by supervisors for attempting to pepper-spray a man sleeping in a bathroom stall in 2000.[35] |

| Steven Bernard Scott | March 31 2000 | Andrew Haynes, Jeremiah Sullivan, Billie David Hancock, Jesse Sanchez, Michael Olsen, Alan Goodwin, Justin Owings, and Mark Ferris | Officers started chasing Scott after he fired several shots at a parked car. Scott began fighting with police and allegedly tried to wrestle a gun away from one officer. He then became unresponsive. Cause of death was ruled as cocaine-induced heart attack.[36] | Grand jury declined to indict.[36] |

| Jose Navarro | July 28, 2001 | Steven McCurley | Police called for two men repeatedly stabbing another man after an argument at a convenience store. McCurley stated that Navarro, who was with the two men, was waving a claw hammer at bystanders. Navarro allegedly turned his aggression toward McCurley, who shot and killed him. | Unknown. |

| Sophia King | June 11, 2002 | John Coffey | King was shot while brandishing butcher knife over her housing development manager.[7] King had a long history of schizophrenia. Police were criticized for failing to call mental health officers when responding to several noise complaints by her neighbors in the days preceding her death.[37] | Grand jury declined to indict. A jury sided with APD in a 2004 wrongful death lawsuit by family.[37] |

| Jesse Lee Owens, Jr. | June 14, 2003 | Scott Glasgow | Glasgow was attempting to handcuff Owens through the car window when Owens accelerated the car and Glasgow's arm became caught and he was dragged. Glasgow shot Owens several times.[38] Glasgow later ranked in the top 25 APD officers in number of use-of-force reports filed from 1998-2003.[35] Scott Glasgow was also involved in the 2014 shooting of Scott Caraway (see below). | Glasgow was indicted for criminally negligent homicide by a grand jury but prosecutors later dropped the charges for insufficient evidence. Glasgow received a 90-day suspension for failure to follow high-risk traffic stop protocol. |

| Daniel Rocha | June 9, 2005 | Julie Schroeder | Rocha was pulled over by Schroeder after leaving a "known drug-house". Rocha allegedly resisted arrest, however several witnesses said they did not see a struggle. Rocha was shot once in the back. Schroeder defended the shooting by saying that Rocha was reaching for her taser.[39] | Grand jury declined to indict. She was fired by APD.[40] |

| Michael Clark | September 26, 2005 | Douglas Drake, Blaine Eiben, Sgt Robert Pewitt, Robin Denton | Police were called for domestic disturbance and arrested Clark for public intoxication. Clark allegedly resisted arrest, with nine officers involved in subduing him - two of whom were injured by Clark. Clark was pepper sprayed and tased three times, after which he went into "medical distress".[41] According to the autopsy report, the cause of death was "the consequences of massive intravascular sickling (sickle cell anemia) associated with extreme physical exhaustion due to PCP and cocaine induced excited delirium". Critics of this arrest say that he died from being tased multiple times in a short period.[42] | No disciplinary actions. Grand jury declined to indict.[43] |

| Kevin Alexander Brown | June 3, 2007 | Michael Olsen | Police were called by security guard who reported a patron with a gun. Brown fled from Olsen on questioning. Olsen said he shot when Brown reached for his waistband while running away, but a witness said Brown was pulling his pants up. A gun was found 20 feet from Brown's body.[44] Olsen had a significant history of use of force prior to the shooting. He was suspended in 2002 for using excessive force on Jeffrey Thornton - a bystander who criticized Olsen's behavior while responding to a civil disturbance. He was additionally suspended for writing a false statement and tampering with government records related to that incident.[45] From 1998-2003, Oslen filed 80 use-of-force reports, the highest among all APD officers. Typical APD officers filed around eight in the same period.[35] | Grand jury declined to indict. Olsen was fired by APD.[7] |

| Nathaniel Sanders II | May 11, 2009 | Leonardo Quintana | Sanders and two other men were sleeping in a parked car that police thought may be related to reports of gunfire in the area. Quintana alleged that Sanders grabbed his hand upon waking up as Quintana reached for the gun in Sanders' waistband. The two wrestled over the gun and, after Sanders regained control of it, Quintana shot him. Sanders had been charged with robbery by assault days earlier and was released on bond. Quintana had nine previous complaints of excessive force which were all overturned. The incident outraged residents, who threw bottles and rocks at police the next morning, smashed several police car windows, and minorly injured several officers.[46] While APD maintained that Quintana acted appropriately, an independent report by KeyPoint Government Solutions (hired by the City of Austin) concluded that Quintana did use excessive force and acted recklessly in several ways, including failing to identify as himself as an officer when waking Sanders up. | Grand jury declined to indict.[47] Quintana was suspended 15 days for failure to activate his patrol car camera. Quintana was fired in 2010 for driving while intoxicated.[48] The family of the victim sued the City of Austin for wrongful death, which resulted in a $750,000 settlement.[49] |

| Devin Contreras | October 1, 2010 | Derrick Bowman | Bowman shot Contreras when he pointed a gun at police outside a Big Lots store during an attempted burglary. Police reported that Contreras had shot first, though later said that examination of his revolver revealed it had not been fired. Patrol car video confirms that Contreras did point a gun at police.[50] The case was somewhat controversial because Bowman fired 14 rounds within three seconds, four of which hit Contreras. The family's attorney claimed that the patrol car video showed Contreras running away and was concerned that Bowman kept firing after Contreras had fallen to the ground.[51] | Grand jury declined to indict. No disciplinary action.[51] |

| Byron Carter, Jr. | May 30, 2011 | Nathan Wagner and Jeffery Rodriguez | Wagner and Rodriguez were patrolling for car thieves and said they began following two individuals who they believed were "casing out the area". The officers found the suspects inside a parked car, with Carter in the passengers seat. Officers were approaching the car with guns drawn when the car lunged toward officers, striking and injuring Rodriguez and pinning Wagner against another car. Wagner says he fired several shots at the car while he was pinned and continued shooting as the car drove away.[52] A police firearms investigator later confirmed that the car was passing Wagner as he shot, not coming towards him.[53] The car was found blocks away with Carter dead inside. He had been shot four times. Officers were on bicycles and not wearing body cameras.[52] A grand jury declined to indict the driver of the car for aggravated assault on an officer. The driver later testified that he did not know it was police approaching the car and that Carter had yelled "Go. Just Go" as if they were in danger.[54] | A grand jury declined to indict the officers. No disciplinary action.[55]

The victim's family sued the City of Austin in 2013 for violation of civil rights, but the jury sided with police.[54] |

| Ahmede Jabbar Bradley | April 5, 2012 | Eric Copeland | Bradley fled on foot from Copeland during a minor traffic stop, which ended in a struggle. Several 911 calls from neighbors confirmed that the two were wrestling over Copeland's gun before Bradley was shot. Copeland did attempt to use his taser on Bradley at one point but said that "one of the prongs did not take". A peaceful protest opposing the shooting was held outside APD headquarters.[56] The NAACP and Texas Civil Rights Project later filed a complaint to the U.S. Department of Justice that they had ended their recent civil rights investigation of APD too early, citing Bradley's shooting.[57] | No disciplinary action. |

| Larry Jackson, Jr. | July 26, 2013 | Detective Charles Kleinert | Jackson entered a bank at which Kleinert was investigating a bank robbery as part of the Federal Violent Crimes Task Force. When bank tellers identified Jackson to Kleinert as a possible participant, Kleinert attempted to question him but Jackson ran. Kleinert chased Jackson and shot him after a struggle. It was later revealed that Jackson was not involved with the bank robbery, was unarmed, and was shot in the back of the neck.[7] | Kleinert was indicted by grand jury for manslaughter. The charges dismissed by U.S. District Judge Lee Yeakel, who cited a precedent that protects federal agents from local prosecution. Yaekel's ruling extended the protection to local officers working on federal task forces.[58] The City of Austin later settled a wrongful death lawsuit from Jackson's family for $1.25 million.[59] |

| Scott Caraway | September 8, 2014 | Shawn Scott, Scott Glasgow, Phillip Hogue | Police were attempting to arrest Caraway in connection with a bank robbery, as part of the Federal Violent Crimes Task Force. Caraway allegedly fired at officers from his car. Officers opened fired and killed Caraway. Scott Glasgow was also involved in the 2003 shooting of Jesse Lee Owens (see above). | Cleared by federal officials. |

| David Joseph | February 8, 2016 | Geoffrey Freeman | Freeman responded to calls about a man chasing another man through an apartment complex. The dispatcher said callers confirmed the two men were unarmed. Freeman encountered Joseph naked and standing in the street. Freeman exited his vehicle, intending to wait for backup from a distance, however Joseph charged at him despite orders to stop. Freeman fired two shots, fatally wounding Joseph.[60] Investigation revealed that Freeman had suspected that Joseph was having a mental health crisis based on the 911 calls that the dispatcher was reporting and had called for backup before arriving. He claimed that he exited the car with his gun drawn in order to "kinda hold [Joseph] there" and that he never considered switching to pepper spray or a stun gun, both of which he was carrying. Freeman later said that he did not think his stun gun would work on someone in Joseph's condition.[61] Joseph's autopsy was positive for marijuana and Xanax but authorities thought that Joseph's behavior was due more to a mental health crisis than drug-induced. In the weeks prior to his shooting, friends reported that Joseph had started acting oddly - often referring to himself as one of the three kings from the Bible. The day before the shooting, he told a friend's mother that Lucifer was after him. Two people told police that Joseph walked up to them near where he was shot and said he was "going to see Jesus tonight".[62] | A grand jury declined to indict.

Freeman was fired from APD. Freeman appealed and settled with the City of Austin for $35,000 - an outcome which made him eligible to be hired at other police departments.[63] The City of Austin settled a wrongful death lawsuit by Joseph's family for $3.25 million. Chief of Police Art Acevedo drew criticism from the Austin Police Association when he appeared with Black Lives Matter activists who were protesting the shooting.[60] |

| Jason Sebastian Roque | May 2, 2017 | James Harvel | Police responded to a call that Roque was waving a gun erratically outside. Roque's mother then called 911 and reported that her son was threatening to commit suicide. When police arrived, Roque began to approach his mother, ignoring police orders to freeze.[64] Harvel shot Roque because he did not know where Roque's gun was pointed and was concerned for the mother's safety. Roque's parents later sued the City of Austin for wrongful death - stating that footage of the event showed that Roque dropped his gun after Harvel's first shot and began walking away from it but that Harvel fired two more shots regardless.[65] | Unknown. |

| Landon Nobles | May 7, 2017 | Sgt. Richard Egal, Cpl. Maxwell Johnson | Police monitoring the Sixth Street district heard gunfire following an argument between several people. Officers monitoring cameras of the area radioed a description of the shooter. When officers approached a man matching the description (Nobles), he ran and allegedly shot at officers. The officers returned fire, killing Nobles. His cousin, however, says that an officer threw a bicycle in Nobles' path and that his gun went off as he tripped.[66] The family later sued the City of Austin, citing several witnesses who said Nobles was not displaying a gun and the autopsy finding that Nobles was shot in the back.[67] | District attorney chose not to take the case before a grand jury[68] |

| Mauris DeSilva | July 31, 2019 | Christopher Taylor and two unidentified officers. | Police responded to calls of a man banging on fire exit doors at a downtown apartment and holding a knife to his own throat. They found DeSilva, who lived in the building, in the apartment's gym holding a knife to his throat. In response to commands to drop the weapon, DeSilva instead walked toward officers still holding the knife. Two officers shot DeSilva while a third tasered him. DeSilva had a history of depression and manic episodes and the case drew criticism for the APD's handling of mental health crises.[69] According to one study, among the largest 15 U.S. cities, the Austin Police Department had the highest per capita rate of police shootings during mental health calls from 2010-2016.[70] | The district attorney is reviewing the case.[71]

DeSilva's father is currently suing the City of Austin.[69] |

| Michael Ramos | April 24, 2020 | Christopher Taylor | Officers responded to a 911 caller who reported a Hispanic man and a Hispanic woman were using drugs in a car, that the man was holding a gun, and that he had pointed it at the woman.[72][73] Ramos complied with orders to exit the vehicle but did not comply with the officers' other commands. Police shot Ramos with a "bean bag round", at which point he got back in his vehicle. As the car drove away, Taylor shot at the car with a rifle, killing Ramos. No firearms were found in the car or nearby vicinity. Taylor defended his use of lethal force, saying that he thought Ramos intended to use the car as a deadly weapon.[74] Taylor was involved in the lethal shooting of Mauris DeSilva less than 9 months prior, as described above. | Unknown but Taylor did return to active duty, as evidenced by the shooting of DeSilva.

Criminal investigations are still on-going but the Travis County District Attorney announced recently that the case would go before a grand jury.[75] |

Facilities

Austin Police Headquarters

Jaime Padron North Substation[76]

Clinton Warren Hunter Austin Police South Substation

Loyola Neighborhood Center

See also

References

- Sullivan, Carl; Baranauckas, Carla (June 26, 2020). "Here's how much money goes to police departments in largest cities across the U.S." USA Today. Archived from the original on July 14, 2020.

- "APD Administration". City of Austin. Retrieved June 29, 2017.

- "Chief Manley's Biography". City of Austin. Retrieved April 25, 2019.

- "One Austin, Safer Together". City of Austin. Retrieved April 24, 2019.

- Cunningham, Chelsea; Norwood, Kalyn (June 14, 2018). "Austin City Council approves Brian Manley as permanent police chief". KVUE. Retrieved April 25, 2019.

- "Officers Killed in the Line of Duty". austintexas.gov. Retrieved April 25, 2019.

- "Use of Force Deaths in ATX". NAACP: AUSTIN. Retrieved 2020-06-04.

- Shultz, Gary (August 1, 1971). "Police kill suspect". Austin American-Statesman.

- Be Saw, Larry (August 6, 1971). "City Council Urged to Stop Bloodshed". Austin American-Statesman.

- "Chief condemns police detractors". Austin American-Statesman. August 7, 1971.

- Fuqua, Wendell (October 8, 1974). "Shooting reports conflict". Austin American-Statesman.

- Fries, Jane (December 18, 1974). "Soto widow sues 2 policemen seeking $83,000 in damages". Austin American-Statesman.

- White, Jerry (February 18, 1985). "Slaying of robber by officer in Ekiye suffocation recalled". Austin American-Statesman.

- Schwab, Robert (August 2, 1979). "Grand jury to probe death". Austin American-Statesman.

- Schwab, Robert (August 22, 1979). "Cops' identity not revealed to Gril Couch". Austin American-Statesman.

- Schwab, Robert (August 21, 1979). "Dyson rewrites police policy on death reviews". Austin American-Statesman.

- Schwab, Robert (September 5, 1979). "Dyson orders inquiry into roughnesss complaint". Austin American-Statesman.

- Schwab, Robert (January 15, 1980). "2nd cop involved in Gril Couch case to resign next week". Austin American-Statesman.

- Everett, Trent (January 28, 1980). "Fleeing suspect shot, dies". Austin-American Statesman.

- Sutton, John (February 13, 1980). "Jury indicts no one in burglary slaying". Austin American-Statesman.

- White, Jerry (December 28, 1984). "Nigerian death charges refused by grand jury". Austin American-Statesman.

- White, Jerry (September 13, 1985). "Mattox finds 4 lawmen negligent in death of Nigerian". Austin American-Statesman.

- White, Jerry (February 18, 1985). "Nigerian death spurs revised medical training". Austin American-Statesman.

- White, Jerry (March 9, 1985). "Nigerian official to investigate policemen's role in suffocation". Austin American-Statesman.

- Frink, Charyl Coggins (June 8, 1986). "Picket ends". Austin American-Statesman.

- White, Jerry (September 27, 1985). "Indictment of 4 police officers declined in death of Nigerian". Austin American-Statesman.

- Harris, John (October 31, 1990). "Officer kills teen aiming pistol". Austin American-Statesman.

- Banta, Bob (November 29, 1990). "Officer cleared in death of teen". Austin American-Statesman.

- Phillips, Jim (May 20, 1992). "Car drags policeman; suspect says he was hit". Austin American-Statesman.

- Banta, Bob (January 28, 1998). "Man's death after fight with police examined". Austin American-Statesman.

- Banta, Bob (February 3, 1998). "Poison cited in death of man in police fight". Austin American-Statesman.

- Banta, Bob (March 4, 1999). "Austin Police Shooting is Third This Year". Austin American-Statesmen.

- Osborn, Claire (September 24, 1999). "Suspect in assault dies after arrest; substance abuse possible". Austin American-Statesman.

- Ruland, Patricia (September 28, 2007). "The Millionaire Who Would Be Constable". The Austin Chronicle.

- Rodriguez, Erik (January 27, 2004). "Policing themselves". Austin American-Statesmen.

- "Austin police cleared in man's death". Austin-American Statesman. May 13, 2000.

- Tak, Skrey (January 23, 2006). "Death of Sophia King: Office didn't know of illness, city's lawyer says". Austin-American Statesman.

- Smith, Jordan; Fri.; Dec. 12; 2003. "'Something Went Wrong'". www.austinchronicle.com. Retrieved 2020-06-05.CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link)

- "Officer fatally shoots teen". Austin American-Statesman. June 11, 2005.

- Plohetski, Tony (November 22, 2005). "Internal review: Rocha shooting broke no rules". Austin American-Statesman.

- Humphrey, Katie (September 28, 2005). "Man who died in custody had multiple Taser injuries". Austin American-Statesman.

- Stanley, Dick (October 29, 2005). "Report: Taser did not kill man". Austin American-Statesman.

- Plohetski, Tony (March 28, 2006). "No discipline for officers in fatal arrest". Austin American-Statesman.

- Gonzales, Suzannah (June 4, 2007). "Officer shoots, kills man". Austin American-Statesman.

- Osborn, Claire (August 8, 2003). "Austin officer accused of filing false report is indicted". Austin American-Statesmen.

- Plohetski, Tony (May 12, 2009). "Questions about use of deadly force renewed". Austin American-Statesman.

- Plohetski, Tony (August 6, 2009). "Officer who shot suspect not indicted". Austin American-Statesman.

- Plohetski, Tony (May 8, 2010). "Acevedo stands by decision the shooting was 'objectively reasonable'". Austin American-Statesmen.

- George, Patrick (October 21, 2011). "Autopsy: Passenger was shot 4 times". Austin American-Statesman.

- Heinauer, Laura (October 3, 2010). "Friends of slain teen raise money for his funeral". Austin American-Statesman.

- Plohetski, Tony (February 25, 2011). "No charges for officer who shot teen in burglary". Austin American-Statesman.

- Grisales, Claudia (June 1, 2011). "Police shoot, kill man, wound teen". Austin American-Statesman.

- Ulloa, Jazmine (June 11, 2013). "Closing arguments set Tuesday in civil rights suit". Austin American-Statesman.

- Ulloa, Jazmine (June 12, 2013). "Jury sides with police in lawsuit over civil rights in fatal shooting". Austin American-Statesman.

- Plohetski, Tony (March 10, 2012). "Police officer not indicted in fatal shooting". Austin American-Statesman.

- Mashhood, Farzad (April 11, 2012). "Peaceful rally at police headquarters protests use of force". Austin American-Statesman.

- George, Patrick (June 28, 2012). "Civil rights groups as U.S. to re-examine Austin police". Austin American-Statesman.

- Plohetski, Tony (November 9, 2015). "Critics: Law creates accountability issue". Austin American-Statesman.

- Plohetski, Tony (February 15, 2017). "Austin payout might top $2M in police shooting". Austin American-Statesman.

- Urbanszewski, Katie (May 18, 2016). "Cop avoids charge in killing of Joseph". Austin American-Statesman.

- Plohetski, Joseph (November 9, 2016). "Officer who shot unarmed, naked teen David Joseph: 'I defended myself'". Austin American-Statesman.

- Hall, Katie (July 2, 2016). "Before being shot, teen said he was 'going to see Jesus'". Austin American-Statesman.

- Jankowski, Phillip (February 17, 2017). "Council OKs $3.25M in Joseph case". Austin American-Statesman.

- Hicks, Nolan (May 5, 2017). "Police identify officer in shooting". Austin American-Statesman.

- Powell, Jacqulyn (September 28, 2017). "Parents of man killed by APD officer suing the city of Austin". KXAN News.

- Wilson, Mark (May 9, 2017). "Cousin disputes cops' report of shooting". Austin American-Statesman.

- Wilson, Andrew (April 8, 2019). "Family claims in lawsuit Austin officers shot man in back several times". KXAN News.

- Wilson, Andrew (November 27, 2018). "District Attorney rules Austin officers' use of deadly force in Landon Nobles' death was justified". KXAN News.

- Raji, Michelle (June 4, 2020). "Why Is APD Responding To Mental Health Crises Like Violent Crimes?". The Texas Observer.

- Osbourne, Heather (September 24, 2019). "Austin leads in police shootings during mental health calls, study finds". Austin American-Statesman.

- “Pending Police-Involved Shooting Investigations.” Austin, TX.

- "911 call that led up to Michael Ramos' death raises questions about caller's culpability". kvue.com. Retrieved 2020-08-10.

- Spencer, Bridget (2020-07-27). "APD releases Mike Ramos officer-involved shooting video". FOX 7 Austin. Retrieved 2020-08-10.

- "Mother seeks answers from Austin police chief following death of her son". KXAN Austin. 2020-06-01. Retrieved 2020-06-10.

- Austin, C. B. S. (2020-05-29). "Shooting death of Mike Ramos by APD officer to be presented to grand jury". KEYE. Retrieved 2020-06-10.

- Doolittle, Dave (September 26, 2018). "Police substation to be named after Jaime Padron". Austin American-Statesman. Retrieved February 25, 2020.