Armadillo World Headquarters

Armadillo World Headquarters (The 'Dillo or Armadillo WHQ) was an influential Texas music hall and beer garden in Austin at 5251⁄2 Barton Springs Road – at South First Street – just south of the Colorado River and downtown Austin. The 'Dillo flourished from 1970 to 1980.[1][2][3][4] The structure that housed it, an old National Guard Armory, was demolished in 1981 and replaced by a 13-story office building.[5]

History

In 1970, Austin's flagship rock music venue, the Vulcan Gas Company, closed, leaving the city's nascent and burgeoning live music scene without an incubator. One night, Eddie Wilson, manager of the local group Shiva's Headband, stepped outside a nightclub where the band was playing and noticed an old, abandoned National Guard armory.[6] Wilson found an unlocked garage door on the building and was able to view the cavernous interior using the headlights of his automobile. He had a desire to continue the legacy of the Vulcan Gas Company, and was inspired by what he saw in the armory to create a new music hall in the derelict structure. The armory was estimated to have been built in 1948, but no records of its construction could be or have been located. The building was ugly, uncomfortable, and had poor acoustics, but offered cheap rent and a central location. Posters for the venue usually noted the address as 525½ Barton Springs Road (Rear), behind the Skating Palace (approximate coordinates 30.258 −97.750).

The name for the Armadillo was inspired by the use of armadillos as a symbol in the artwork of Jim Franklin,[7] a local poster artist, and from the building itself. In choosing the mascot for the new venture, Wilson and his partners wanted an "armored" animal since the building was an old armory. The nine-banded armadillo (Dasypus novemcinctus) was chosen because of its hard shell that looks like armor, its history as a survivor (virtually unchanged for almost 50 million years), and its near-ubiquity in Central Texas. Wilson also believed the building looked like it had been some type of headquarters at one time. He initially proposed "International Headquarters" but in the end it became "World Headquarters."

In founding the Armadillo World Headquarters,[8] Wilson was assisted by Jim Franklin,[7] Mike Tolleson (né Robert Michael Tolleson; born 1942), an entertainment attorney licensed by the State Bar of Texas in 1968, Bobby Hedderman from the Vulcan Gas Company and Hank Alrich. Funding for the venture was initially provided by Shiva's Headband founder's father, Dan Perskin, and Mad Dog, Inc. an Austin literati group that included Bud Shrake.

The Armadillo World Headquarters officially opened on August 7, 1970, with Shiva's Headband, the Hub City Movers, and Whistler performing.[9]

The Armadillo caught on quickly with the hippie culture of Austin because admission was inexpensive and the hall tolerated cannabis use. Even though illicit drug use was flagrant, the Armadillo was never raided. Anecdotes suggest the police were worried about having to bust their fellow officers as well as local and state politicians.

Soon, the Armadillo started receiving publicity in national magazines such as Rolling Stone. In a story from its September 9, 1974, edition, Time magazine wrote that the Armadillo was to the Austin music scene what The Fillmore had been to the emergence of rock music in the 1960s. The clientele became a mixture of hippies, cowboys, and businessmen who stopped by to have lunch and a beer and listen to live music. As Gary Nunn put it, "It's been said that our music was the catalyst that brought the shit-kickers and the hippies together at the Armadillo."[10] At its peak, the amount of Lone Star draft beer sold by the Armadillo was second only to the Houston Astrodome. The Neiman Marcus department store even offered a line of Armadillo-branded products.

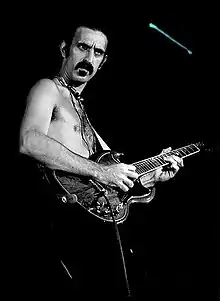

The unique blend of country and rock music performed at the hall became known by the terms "The Austin Sound," "Redneck Rock," progressive country or "Cosmic Cowboy."[11] Artists that almost single-handedly defined this particular genre and sound were Michael Martin Murphey, Jerry Jeff Walker and The Lost Gonzo Band.[12][13] Many upcoming and established acts such as Willie Nelson, Waylon Jennings, Ray Charles, Stevie Ray Vaughan and ZZ Top played the Armadillo. Freddy Fender, Freddie King, Frank Zappa, Commander Cody and His Lost Planet Airmen, The Sir Douglas Quintet all recorded live albums there. Bruce Springsteen played five shows during 1974. The Australian band AC/DC played their first American show at the Armadillo with Canadian band Moxy in July 1977. The Clash played live at The Armadillo with Joe Ely on October 4, 1979 (a photo from that show appears on the band's London Calling album) and the notorious Austin punk band The Skunks.[14]

Despite its successes, the Armadillo always struggled financially. The addition of the Armadillo Beer Garden in 1972 and the subsequent establishment of food service were both bids to generate steady cash flow.[9] However, the financial difficulties continued. In an interview for the 2010 book Weird City, Eddie Wilson remarked:

"People don't remember this part: the months and months of drudgery. People talk about the Armadillo like it was a huge success, but there were months where hardly anyone showed up. After the first night when no one really came I ended up crying myself to sleep up on stage."

This predicament was blamed on a combination of large guaranteed payments for the acts, cheap ticket prices, and poor promotion. The club finally had to lay off staff members in late 1976 and file for Chapter 11 bankruptcy in 1977. Another factor in the club's demise was that it sat on 5.62 acres (22,700 m2) of land in what soon became a prime development area in the rapidly growing city. The Armadillo's landlord sold the property for an amount estimated between $4 million and $8 million.

The final concert at the Armadillo took place on December 31, 1980.[15] The sold-out New Year's Eve show featured Asleep at the Wheel and Commander Cody and the Lost Planet Airmen. Some reports say the show ended at 4 am, while others claim that the bands played until dawn. The contents of the Armadillo were sold at auction in January 1981, and the old armory was razed for a high-rise office building.

Selected artists featured at Armadillo World Headquarters

- AC/DC[16]

- Jay Boy Adams[lower-roman 1]

- April Wine

- The Amazing Rhythm Aces[17]

- Joan Armatrading

- Asleep at the Wheel

- Austin Ballet Theatre[6][18]

- Hoyt Axton

- The B-52's[16]

- Balcones Fault

- Long John Baldry

- Captain Beefheart[19]

- Beto y Los Fairlanes

- Dickey Betts

- Elvin Bishop[17]

- Blackfoot

- Blue Öyster Cult

- Tommy Bolin

- Karla Bonoff[17]

- The Boomtown Rats

- Brewer & Shipley

- David Bromberg

- Clarence "Gatemouth" Brown

- James Brown

- Brownsville Station

- Bill Bruford

- Bubble Puppy

- Roy Buchanan

- Budgie

- Jimmy Buffett[6]

- Ray Campi

- Charlie Daniels Band[17]

- Harry Chapin[17]

- Cheech and Chong[16]

- Clifton Chenier

- Clamtones

- The Clash

- Jimmy Cliff

- Joe Cocker

- David Allan Coe

- Ry Cooder

- Alice Cooper

- Elvis Costello

- James Cotton

- Papa John Creach

- Alvin Crow

- Dead Boys

- Denim

- Rick Derringer

- Devo

- Dire Straits

- The Dixie Dregs

- Joe Ely[14]

- John Fahey

- Dr. Feelgood

- Fats Domino[6]

- Ramblin' Jack Elliott

- Jon Emery

- Roky Erickson[19]

- The Fabulous Thunderbirds

- José Feliciano

- Freddy Fender

- Flying Burrito Brothers[17]

- Michael Franks

- Steven Fromholz

- Jerry Garcia Band[16]

- Jerry Garcia and Merl Saunders[16]

- Gasolin'

- The J. Geils Band

- Genesis

- Gentle Giant

- Egberto Gismonti

- Golden Earring

- Steve Goodman

- Robert Gordon

- Greezy Wheels[17]

- David Grisman

- Larry Groce

- Stefan Grossman & John Renbourn

- Arlo Guthrie[17]

- Haciendo Punto

- John P. Hammond

- John Hartford

- Emmylou Harris[17]

- Alex Harvey

- Richie Havens

- Head East

- Levon Helm

- Bugs Henderson[17]

- Dan Hicks & the Hot Licks

- John Lee Hooker

- Lightnin' Hopkins

- Horslips

- Hot Tuna

- Hub City Movers[9]

- It's a Beautiful Day

- The Jam

- Bert Jansch

- Waylon Jennings[16][13]

- Eric Johnson

- Rickie Lee Jones

- Janis Joplin

- Journey

- Joy of Cooking

- Jules and the Polar Bears

- Madleen Kane

- Kansas

- Doug Kershaw

- John Klemmer

- Freddie King[21][19]

- The Kinks[17]

- Leo Kottke

- Kraftwerk

- Peter Lang

- Alvin Lee[17]

- LeRoux

- Jerry Lee Lewis[17]

- Gordon Lightfoot

- Mance Lipscomb

- Little Feat[17]

- Kenny Loggins

- The Lost Gonzo Band

- Lynyrd Skynyrd[16]

- Taj Mahal[17]

- Mahogany Rush

- Man Mountain and the Green Slime Boys[lower-roman 3]

- The Marshall Tucker Band

- Bob Marley

- Moon Martin

- Dave Mason

- Mary McCaslin

- Delbert McClinton

- Country Joe McDonald

- Roger McGuinn

- Augie Meyers

- Bette Midler[6]

- Buddy Miles[17]

- El Molino[20][lower-roman 2]

- Bill Monroe

- Van Morrison

- Moxy

- Maria Muldaur

- Martin Mull

- Michael Martin Murphey[12]

- Willie Nelson[21][19]

- Michael Nesmith[17]

- New Riders of the Purple Sage[22]

- The Nitty Gritty Dirt Band

- Ted Nugent

- Phil Ochs[17]

- Robert Palmer

- Gram Parsons

- Turk Pipkin

- The Plimsouls

- The Police[16]

- Iggy Pop

- Pousette-Dart Band

- Pure Prairie League[17]

- The Pretenders

- John Prine[17]

- Paul Ray (1942–2016) and the Cobras

- Radio Birdman

- The Ramones

- Kenny Rankin

- Leon Redbone[17]

- Renaissance

- Rockpile

- Johnny Rodriguez

- Linda Ronstadt[17]

- Root Boy Slim

- The Rowan Brothers

- Roxy Music

- The Runaways

- Todd Rundgren

- Rush

- Leon Russell

- Doug Sahm

- Don Sanders

- San Francisco Mime Troupe[6]

- Savoy Brown

- Boz Scaggs

- Earl Scruggs[9]

- Seals & Crofts

- Pete Seeger

- Bob Seger

- Ravi Shankar[9]

- Shiva's Headband[9]

- Silicon Teens

- The Sir Douglas Quintet

- The Skunks

- Skyhooks

- Margo Smith

- Patti Smith

- Chris Smither

- Jimmie Spheeris

- Spirit

- Bruce Springsteen[16][6]

- Squeeze

- St. Elmo's Fire (band)

- Steeleye Span

- Steely Dan

- B.W. Stevenson

- Stoneground

- The Take

- Talking Heads[17]

- Chip Taylor

- Sonny Terry & Brownie McGhee

- Thin Lizzy

- George Thorogood

- Kenneth Threadgill

- Too Smooth

- Toots & the Maytals

- Toto

- Ralph Towner

- The Tubes

- Pat Travers

- TT Troll

- Uranium Savages[17]

- Van Halen[16]

- Townes Van Zandt

- Gino Vannelli

- Stevie Ray Vaughan[16]

- Loudon Wainwright III

- Tom Waits

- Jerry Jeff Walker[12]

- Doc and Merle Watson

- Bob Weir

- Wet Willie

- Rusty Wier

- Edgar Winter[17]

- Johnny Winter[17]

- Jimmy Witherspoon

- The Wommack Bros. Band

- XTC

- Frank Zappa[16][6]

- ZZ Top[17]

- John Abercrombie

- Mose Allison[17]

- Art Ensemble of Chicago

- Gato Barbieri

- Count Basie[6]

- Carla Bley

- Blood, Sweat & Tears[17]

- Anthony Braxton

- Brecker Brothers

- Dave Brubeck[17]

- Charlie Byrd[17]

- Gary Burton

- Ray Charles[16][6]

- Billy Cobham

- Larry Coryell

- Coryell and Mouzon

- Jack DeJohnette Special Edition

- The Electromagnets[23][lower-roman 4]

- Herb Ellis[17]

- Sonny Fortune

- Jan Garbarek

- Dexter Gordon

- Great Guitars

- Jan Hammer

- Herbie Hancock

- Eddie Harris

- Heath Brothers

- Keith Jarrett

- Al Kooper[17]

- Yusef Lateef

- Jeff Lorber Fusion

- Mahavishnu Orchestra

- Chuck Mangione[17]

- Pat Metheny

- Charles Mingus

- Old and New Dreams

- The Pointer Sisters[16]

- Flora Purim

- Sonny Rollins

- David Sanborn

- Gil Scott-Heron

- Woody Shaw

- Spyro Gyra

- Naná Vasconcelos

- The Miroslav Vitouš Group

- Weather Report

- Lenny White

- The Paul Winter Consort

- Phil Woods

Live recordings made at the Armadillo

Progressive country, rock, blues, punk

- Commander Cody and His Lost Planet Airmen: Sleazy Roadside Stories

- Commander Cody and His Lost Planet Airmen: Live from Deep in the Heart of Texas (1974); OCLC 872055098

- Frank Zappa, Captain Beefheart, The Mothers: Bongo Fury (1975)

- Frank Zappa (lead guitar, vocals); George Duke (keyboards); Captain Beefheart (harmonica, vocals, shoppy bags); Bruce Fowler (trombone); Tom Fowler (bass); Denny Walley (guitar, vocals); Terry Bozzio (drums)

- Recorded May 20 & 21, 1975; "200 Years Old" and "Muffin Man" intros were recorded in January and February 1974 at the Record Plant, Los Angeles; OCLC 743162154, 800122561

- Back-side of the album cover: "Special thanks to the kitchen staff at The Armadillo, especially Jan Beeman" (née Janelle Gay Hopper; 1934–2007)[24]

- New Riders of the Purple Sage: Armadillo World Headquarters, Austin, TX, 6/13/75 (1975)

- Sir Douglas Quintet, Freddy Fender, Roky Erickson: Re-Union of the Cosmic Brothers (1975)

- Waylon Jennings: Waylon:Live (1976)[13]

- Sir Douglas Quintet: Live Love (1977)

- Doug Sahm, Augie Meyers & Friends: Wanted: Dead or Alive (1977)

- The Bugs Henderson Group: At Last – Recorded Live on Stage (1978)

- The Cobras: Live & Deadly

- Cobras: Denny Freeman (guitar), Larry Lange (bass), Rodney Craig (drums), Joe Sublett (né Joseph M. Sublett; born 1953) (saxophone), Paul J. Constantine (born 1950) (trumpet), Larry Medlow "Junior Medlow" Williams Jr. (1953–1997) (vocals, rhythm guitar), also with Angela Strehli & Paul Ray (né Paul Henry Ray; 1942–2016) (vocals)

- Recorded November 1979, released in 2011; OCLC 904409936

Jazz

- Freddie King; with David "Fathead" Newman and Jerry Jumonville: Larger Than Life (some tracks, not full record)[21]

- Freddie King (vocals, guitar); John Thomas, Darrell Leonard (trumpets); Jerry Jumonville (tenor and alto sax); David "Fathead" Newman (tenor sax); Jim Gordon (né James Wells Gordon) (tenor sax, organ); Joe Davis (né Joe Lane Davis; 1941–1995) (bari sax); Alvin Hemphill (organ); K.O. Thomas, Louis Stephens (piano); Michael O'Neill and Andrew "Jr. Boy" Jones (guitar); Robert G. Wilson (1956–2010), Bennie Turner (bass guitar); Charles Myers, Big John E. Thomassie (1949–1996) (drums); Sam Clayton (congas)

- Recorded April 1975; RSO SO-4811

- Carla Bley

- Mike Mantler (trumpet); Gary Windo (sax); Alan Michael Braufman (saxophone); John Clark (french horn); George Lewis (trombone); Bob Stewart (tuba); Blue Gene Tyranny (keyboards); Patty Price (bass); Phillip Wilson (drums)

- Recorded March 27, 1978; Hi Hat HHHCD3112

- Phil Woods Quartet – 2 releases: Live (1978) and More Live

- Mike Melillo (piano); Steve Gilmore (bass); Bill Goodwin (drums)

- Recorded May 23 & 26, 1978; Aledphi AD5010; OCLC 9617686, 153920622, 763120503, 1187400833, 35266949, 725169019, 611560736

- Anthony Braxton (solo alto sax) (1978)

- Recorded October, 1978; released March 2011, Braxton Bootleg Records BL007[lower-roman 5]

Selected people

Music poster artists (alphabetical)

Posters by the following artists were part of the iconic artwork that helped define Armadillo World Headquarters in the 1970s – "The Armadillo Art Squad:"

- Michael Edward Arth (de) (born 1953)

- Kerry Awn

- Ken Featherston (né Kenneth Wayne Featherston; 1951–1975)

- Jim Franklin (born 1943)[25] drew his first armadillo – smoking a joint – on a hand-bill for a 1968 love-in. Twenty-seven years later, in 1995, Texas designated the nine-banded armadillo (dasypus novemcinctus) as the official state small mammal. Franklin has been called the "Michelangelo of armadillo art."[26][27][28]

- Danny Garrett[25][29]

- Henry Gonzalez (né Enrique Barrientos Gonzalez; 1950–2016)[25][2]

- Guy Juke[30]

- Bill Narum (né William Albert Narum; 1947–2009)

- Micael Priest (1951–2018)[25]

- Dale Wilkins (né Dale Evan Wilkins; born 1949)

- Sam Yeates (né Samuel Wade Yeates; born 1951)

Photographer

Vermont-born Burton Wilson (né Burton Estey Wilson; 1919–2014) – no relation to Eddie – was the de facto house photographer for the Vulcan Gas Company and Armadillo World Headquarters. Eddie Wilson once told him, "Just tell anybody who asks that you own the place. That way, you'll never need a backstage pass."[31][32][33][34][35]

Legacy

Austin City Limits

With the success of the Armadillo and Austin's burgeoning music scene, KLRN (now KLRU), the local PBS television affiliate, created Austin City Limits, a program showcasing popular local, regional, and national music acts.

Historical marker

On August 19, 2006, the City of Austin dedicated a commemorative historical plaque that had been installed in the parking lot of One Texas Center, where the Armadillo once stood. The Texas Monthly, in its 1999 "Best of the Texas Century" edition, named Armadillo World Headquarters as the "Venue of the Century."[36]

It is still on the lips and minds of a lot of people 26 years after it closed. This is noteworthy for me because of the zero-tolerance mentality, and now the city erected a memorial that glorifies the things of the past that are not accepted today.

— Eddie Wilson, August 19, 2006

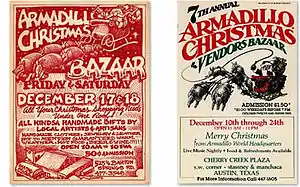

Armadillo Christmas Bazaar

The Armadillo Christmas Bazaar began in 1976, forty-four years ago, at the Armadillo, and, except for 2020, has been held annually. The bazaar began as a collaboration to give indoor space to artisan vendors who sold their wares at the Austin Renaissance Market on 23rd Street, near the University of Texas campus – and at the same time, improve cash flow for the hall. When the Armadillo permanently closed, the bazaar moved to Cherry Creek Plaza (1981–1983) and then on to the Austin Opry House at 200 Academy Drive (1984–1994). In 1995, the bazaar settled for twelve years at the Austin Music Hall, 208 Nueces Street at Third Street. Due to remodeling of the Austin Music Hall, the bazaar moved its 2007 show to the Austin Convention Center and is currently at the Palmer Events Center at Auditorium Shores. The bazaar has become a nationally acclaimed arts and crafts fair[37] with a formidable waiting list of artisan vendors. On October 12, 2020, the organizers announced the cancellation of the in-person portion of the 2020 bazaar due to the COVID-19 pandemic.

See also

- Folk Music Club

- Music of Austin

Annotations

- Jay Boy Adams (né James Wallace Adams, Jr.; born 1949) is a singer, mostly country, but toured in the 1970s and 1980s with ZZ Top, The Band, Jackson Browne, The Marshall Tucker Band, and Joe Cocker.

- The El Molino band, in 1976, included Ike Ritter (né Frank Joseph Richard Ritter; 1946–1995) (guitar), David Mercer (né Frank David Alin Mercer; born 1951; Bill Mercer's son) (Farfisa organ), "Rocky" Morales (né Eracleo Mario Morales; 1940–2006) (tenor sax), Charlie McBurney (né Charles C. McBurney, Jr.; 1945–2003) (trumpet), Speedy Sparks (né Miller Vidor Sparks, Jr.; born 1945) (bass), Arturo "Sauce" Gonzales (né Tomás Arturo González; born 1943) (keyboards), and duelling drummers, Ernie "Murphey" Durawa (né Ernest Saldana Durawa; born 1942) and Richard "eh eh" Elizondo (deceased) – nicknamed "El Pinguino" – who, while in Junior High in San Antonio, played with Doug Sahm. In 1979, Joe King Carrasco swapped El Molino for the Crowns. (Bentley)

- Man Mountain and the Green Slime Boys, from San Antonio, opened for Willie Nelson at Armadillo World Headquarters in 1973.

- The Electromagnets were/was a jazz oriented group that flourished in Austin from 1973 to 1977. The group was composed of Eric Johnson (né David Eric Johnson; born 1954 in Austin) (guitar), Stephen Barber (electric piano), Kyle Brock (né Kyle Glen Brock; born 1951) (bass), and Bill "Thunderball" Maddox (né William Leslie Maddox; 1953–2010) (drums). Their music has been described as experimental electric, in a jazz genre, in the spirit of Miles Davis, Joe Zawinul, and Chick Corea. (Doerschuk)

- Braxton Bootleg Records is a project of the Tri-Centric Foundation, a Connecticut non-profit organization that supports the work and legacy of American composer and musician Anthony Braxton. (Tri-Centric website)

- An inscription on the historical marker credits Sam Yeats [sic] for the illustration included in the collage, but earlier prints show the initials "JFKLN", the signature of Jim Franklin.

Notes

- Richards.

- Gonzalez.

- Zelade, pp. 46–49.

- Menconi.

- Gaylord.

- McComb, pp. 35–36.

- Franklin, p. 23.

- Wilson, Eddie.

- Shank, pp. 53–56.

- Nunn.

- Allen, pp. 288–289.

- Hillis.

- Stimeling.

- "Joe Ely".

- "Rollicking Texas", p. A10.

- Long, p. 29.

- Kelso, p. B1.

- Clark.

- England, p. 45.

- Bentley.

- Reid, p. 7.

- Horowitz.

- Doerschuk, p. 45.

- Buchholz, p. B1.

- Patoski & Jacobson.

- Weiseman & Smith, pp. 47.

- Nye, p. 7.

- Richmond.

- Garrett.

- Juke.

- "Vermont Vital Records.

- Wilson, Burton 2001, (back of dust jacket).

- Wilson, Burton 1971.

- Wilson, Burton 1977.

- Blackstock, p. B4.

- Hall.

- Hoinski.

References

News media

- Bentley, Bill (October 11, 2002). "The Ballad of El Molino – Unearthing One of the Great 'Lost' Albums in Texas Rock & Roll History". Austin Chronicle. 22 (6). Retrieved October 14, 2020.

- Blackstock, Peter Mathis (June 3, 2014). "Photographer Burton Wilson Dies at Age 95 – Lensman Captured Heady Austin Music Scene of '60s, 70s". Austin American-Statesman. 143 (313). Retrieved October 19, 2020 – via Newspapers.com.

- Buchholz, Brad (April 13, 2007). "Armadillo's Cook Fed Grateful Musicians". Austin American-Statesman. 136 (259). p. B1. ISSN 0199-8560. Retrieved October 12, 2020 – via Newspapers.com.

- Doerschuk, Bob (né Robert Lindsey Doerschuk; born 1951) (June 21, 1974). "'Electro-Magnets' – Musical Group Grabs Spotlight". Austin American-Statesman. 61 (16). ISSN 0199-8560. Retrieved October 12, 2020 – via Newspapers.com.

- Hoinski, Michael (December 9, 2010). "GTT: Interesting Things in Texas This Week – Austin, Jingle Bell Shop". The New York Times. GTT (Gone to Texas) (online ed.). Retrieved October 15, 2020.

- Kelso, John G. (1944–2017) (February 9, 1980). " 'Dillo Demise a Sad Loss". Austin American-Statesman. 110 (202). p. B1. ISSN 0199-8560. Retrieved October 12, 2020 – via Newspapers.com.

- "Rollicking Texas Honky-Tonk Hears Its Last Chord". The New York Times (Special to The New York Times). 130 (44, 816). January 2, 1981. p. B1. Retrieved October 19, 2020 – via TimesMachine.

Books, journals, magazines, and papers

- Allen, Michael Robert, PhD (Autumn 2005). " 'I Just Want to Be a Cosmic Cowboy': Hippies, Cowboy Code, and the Culture of a Counterculture". Western Historical Quarterly. 36 (3): 275–299. doi:10.2307/25443192. ISSN 0043-3810. JSTOR 25443192. OCLC 5556736269.

- Clark, Caroline Sutton (December 2016). A History of Austin Ballet Theatre at the Armadillo World Headquarters (PDF) (PhD – Department of Dance, College of Arts and Sciences). Texas Woman's University. OCLC 984940245. Retrieved October 9, 2020.

- England, Nelson (Autumn 2005). "Texas Music". Texas Highways. 51 (6): 38–47. ISSN 0040-4349 – via Portal to Texas History.

- Franklin, Jim (né James Knox Franklin, Jr.; born 1943) (March 4, 2000). "Grand Opening of Armadillo World Headquarters, August 7 & 8, 1970". Texas State Historical Association One Hundredth and Fourth Annual Meeting – via Portal to Texas History poster – Note: an original poster – 113⁄16 in. (284.2 mm) × 1613⁄16 in. (427.0 mm) – is held by the Dolph Briscoe Center for American History

- Garrett, Danny (2015). Weird, Yet Strange: Notes From an Austin Music Artist (1st ed.). TCU Press. ISBN 978-0-875-65616-8. OCLC 912045317.

- Hall, Michael (December 1999). "Venue of the Century – Armadillo World Headquarters". Texas Monthly (Special Issue: The Best of the Texas Century). 27 (12).

- Hillis, Craig D. (2002). "Cowboys and Indians: The International Stage" (PDF). Journal of Texas Music History. San Marcos, Texas: Institute for the History of Texas Music, Texas State University. 2 (1). ISSN 1535-7104. OCLC 1120872697. Retrieved February 26, 2017 – via Berkeley Electronic Press.

- Horowitz, Hal (né Harold I. Horowitz; born 1954) (n.d.). "New Riders of the Purple Sage – Austin Texas 1975". AllMusic. Retrieved May 11, 2018.

- "Joe Ely – Live Shots". myreccollection.livejournal.com (blog). LiveJournal. September 24, 2008.

- Juke, Guy (1980). Juke, Visual Thrills: 44 Posters and Paintings. Void of Course Pub. Co. OCLC 8015494.

- Long, Joshua (May 1, 2010). Weird City: Sense of Place and Creative Resistance in Austin, Texas (1st ed.). University of Texas Press. ISBN 0-29-272241-9 (preview via Google Books).

- McComb, David Glendinning, PhD (born 1934) (September 1, 2008) [1st ed.; 2002]. Spare Time in Texas: Recreation and History in the Lone Star State. Jack and Doris Smothers series in Texas history, life, and culture. University of Texas Press – via Internet Archive.

- Menconi, David Lawrence (1985). Music, Media and the Metropolis: The Case for Austin's Armadillo World Headquarters (M.A. in journalism thesis). University of Texas at Austin.

- Nunn, Gary (2018). At Home With the Armadillo. 44. Austin: Greenleaf Book Group Press. p. 198. ISBN 9-781-6-2634487-7. OCLC 992748564.

- Nye, Hermes (né Howard Hermes Nye, Jr.; 1908–1981) (author); Abernethy, Francis Edward (1925–2015) (ed.) (1982). "Goin' Home With the Dasypus Novemcinctus the Mystique of the Armadillo". ← article – book → T for Texas: A State Full of Folklore. 44. Texas Folklore Society (Dallas: E-Heart Press). pp. 3–13. ISBN 0-935-01403-9. LCCN 82-70089. OCLC 555718213. Retrieved October 14, 2020 – via Portal to Texas History.CS1 maint: extra text: authors list (link)

- Patoski, Joe Nick (essays); Jacobson, Nels (essays) (2015). Schaefer, Alan (ed.). Homegrown: Austin Music Posters 1967 to 1982. Austin: University of Texas Press. ISBN 978-0-292-77239-7. OCLC 958883275. Retrieved October 12, 2020.

- Reid, Jan Charles (1945–2020) (March 1, 2004) [1st ed.; Austin: Heidelberg Publishers. 1974]. The Improbable Rise of Redneck Rock (new ed.). University of Texas Press. ISBN 0-29-270197-7. OCLC 217381478 (the book began as an article for Texas Monthly and was then expanded and published by Heidelberg Publishers in Austin)

- Richards, David (2012) [1st ed.; 2002]. Carleton, Don E., PhD. (ed.). Once Upon a Time in Texas: A Liberal in the Lone Star State. Chapter 21: "The Times They Are a Changin''". Austin: University of Texas Press. pp. 175, 179, 182, 212. ISBN 978-0-292-78595-3. OCLC 884576165 (alternate link, limited search, via HathiTrust). Note: Richards, the author, distinguished his career in Texas as a civil rights lawyer; from 1953 to 1984, he was the husband of Ann Richards; a year before they divorced, Ann Richards was elected Texas State Treasurer, which won her the distinction of becoming the first woman (since Ma Ferguson) in 50 years to be elected to a state-wide office; after their divorce, she went on to become the Texas Governor.

- Richmond, Jennifer Lynn (December 2006). Iconographic Analysis of the Armadillo and Cosmic Imagery Within Art Associated With the Armadillo World Headquarters, 1970–1980 (Master of Arts Thesis). Denton: University of North Texas. OCLC 123753696. Retrieved October 14, 2020 – via University of North Texas Libraries, UNT Digital Library.

- Shank, Berry (2011) [1st ed.; Hanover, New Hampshire: University Press of New England. April 15, 1994]. Dissonant Identities: The Rock'n'Roll Scene in Austin, Texas. Middletown, Connecticut: Wesleyan University Press. OCLC 940649616.

- Stimeling, Travis David, PhD (January 2008). "¡Viva Terlingua!: Jerry Jeff Walker, Live Recordings, and the Authenticity of Progressive Country Music" (PDF). Journal of Texas Music History. San Marcos, Texas: Institute for the History of Texas Music, Texas State University. 8 (1). ISSN 1535-7104. OCLC 1120872697. Retrieved February 26, 2017.

- Wilson, Burton Estey (1919–2014) (2001). The Austin Music Scene Through the Lense of Burton Wilson, 1965–1994 (1st ed.). Austin: Eakin Press (Edwin M. Eakin). ISBN 978-1-571-68444-8. OCLC 46383840.

- Wilson, Burton Estey (1919–2014) (1971). Burton's Book of Blues (1st ed.). Austin: Speleo Press; operated by Terry Raines (Terence William Raines; born 1946), publisher of many posters for Armardillo World Headquarters (the word speleo is derived from speleology, the scientific study of caves); Raines is a cave exploration enthusiast.

- Wilson, Burton Estey (1919–2014); forward by Chet Flippo (1977). Burton's Book of the Blues: A Decade of American Music, 1967–1977 (rev. ed.). Austin: Edentata Press (the word edentata, which means toothless, is a species group that includes armadillos). OCLC 473055563.

- Wilson, Eddie (né Edwin Osbourne Wilson) (April 4, 2017). Armadillo World Headquarters. 6416 North Lamar Blvd., Austin, Texas 78752: TSSI Publishing. ISBN 978-1-477-31382-4.CS1 maint: location (link)

- Weiseman, Dale Eric (born 1954); Smith, Joe Griffis (born 1958) (photographer) (December 2002). "The Enduring, Endearing Armadillo" (PDF). Texas Highways. 49 (12): 40–47. ISSN 0040-4349. Retrieved October 14, 2020 – via Portal to Texas History.

- Zelade, Richard Erwin (born 1953) (Winter 1985). "The Armadillo's Last Waltz". Texas Times. Texas Student Media. 6. OCLC 9104814 The Texas Times is a bygone tabloid, monthly except June, printed by the Texas Student Publications, Inc. (UT Austin), under the auspices of the University of Texas System; it launched September 1968

Audio-visual media

- Gaylord, Richard; Hanna, Mark (KTBC) (producers); narrated by Mark Hanna; re-edited in 1994 for the Austin Music Network by Tara Marie Veneruso (born 1972) (1981). The Rise and Fall of the Armadillo World Headquarters (DVD – 27 min., 13 sec.). Austin, Texas: KTBC. OCLC 984128389. Retrieved October 13, 2020 – via YouTube.

- Gonzalez, Henry (né Enrique Barrientos Gonzalez; 1950–2016). "Virtual Tour: Tribute to Two Austin Music Icons – The Armadillo Years: A Visual History". SouthPop (South Austin Popular Culture Center, aka South Austin Museum of Popular Culture). Retrieved May 19, 2017 (via southpop.org) ... Anna Gonzalez (née Anna Margarita Gonzalez; born 1983), was married to visual artist James Richard Everton — website registrant; video was uploaded to YouTube March 11, 2011)

Government and genealogical archives

- "Vermont Vital Records, 1760–1954". FamilySearch (free database with images). May 22, 2014 (searching "Burton Estey Wilson," born October 19, 1919, Derby, Vermont; GS Film: 2073394; Digital Folder: 7011700; Image 1690 of 2859; citing Secretary of State; State Capitol Building; Montpelier)

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Armadillo World Headquarters. |

- awhq.com – Armadillo World Headquarters Official Site (website registrant is Threadgill's Restaurant – officially known as Threadgill's Restaurants, Inc. – which, since the mid-1970s, has been owned by Edwin Osbourne Wilson, co-founder of Armadillo World Headquarters)

- AWHQ Website (archive) (website bears the name of the late artist, Bill Narum (1947–2009), former president of the South Austin Popular Culture Center)

- "Armadillo World Headquarters" (www

.austinlinks is owned by Social Craft Media, LLC, of Austin – Mary Y. Greening, President).com - Armadillo Christmas Bazaar (website is registered to Bruce M. Willenzik (born 1947), who, back in the day, worked at Armadillo World Headquarters)

- Armadillo Photo Archive (website registrant is Steve Hopson, né Steven Bradley Hopson, an Austin-based photographer)

- "Armadillo World Headquarters, 1971–1980" (records)

- "Burton Wilson Collection," photographs of Burton Estey Wilson (1919–2014); OCLC 237061093, 70126159

- "Armadillo World Headquarters records, 1971–1980;" OCLC 70141533

- "Texas Poster Art Collection, 1966–2002"

- "Coke H. Dilworth Photograph Collection, 1972–1977" (né Coke Hairston Dilworth; 1936–1993); OCLC 428978773

- "Calico Printing Posters"

- "Larry Lange Collection" (of The Cobras)