Aymara people

The Aymara or Aimara (Aymara: aymara ![]() listen ) people are an indigenous nation in the Andes and Altiplano regions of South America; about 2.3 million live in Bolivia, Peru and Chile. Their ancestors lived in the region for many centuries before becoming a subject people of the Inca in the late 15th or early 16th century, and later of the Spanish in the 16th century. With the Spanish American Wars of Independence (1810–25), the Aymaras became subjects of the new nations of Bolivia and Peru. After the War of the Pacific (1879–83), Chile annexed territory with Aymara population.[5]

listen ) people are an indigenous nation in the Andes and Altiplano regions of South America; about 2.3 million live in Bolivia, Peru and Chile. Their ancestors lived in the region for many centuries before becoming a subject people of the Inca in the late 15th or early 16th century, and later of the Spanish in the 16th century. With the Spanish American Wars of Independence (1810–25), the Aymaras became subjects of the new nations of Bolivia and Peru. After the War of the Pacific (1879–83), Chile annexed territory with Aymara population.[5]

_1870.jpg.webp) Aymara people in Jujuy Province, c. 1870. | |

| Total population | |

|---|---|

| 2,324,675[1][2][3][4] | |

| Regions with significant populations | |

| 1,598,807[1] | |

| 548,292[2] | |

| 156,754[3] | |

| 20,822[4] | |

| Languages | |

| Aymara • Spanish | |

| Religion | |

| Roman Catholicism • Pachamama • Protestantism • Other Indigenous Religions | |

| Related ethnic groups | |

| Quechuas, Urus | |

History

Archaeologists have found evidence that the Aymaras have occupied the Andes, in what is now western Bolivia for at least 800 years (or more than 5,000 years, according to some estimates, but it is more likely that they are descended from preceding cultures). Their origin is a matter of scientific dispute. The region where Tiwanaku and the modern Aymaras are located, the Altiplano, was conquered by the Incas under Huayna Capac (reign 1483–1523), although the exact date of this takeover is unknown. It is most likely that the Inca had a strong influence over the Aymara region for some time. Though conquered by the Inca, the Aymaras retained some degree of autonomy under the empire.

The Spanish arrived to the western portions of South America in 1535. Soon after, by 1538, they subdued the Aymara. Initially, the Aymara exercised their own distinct culture now free of Incan influence (earlier conquered by the Spanish) but acculturation and assimilation by the Spanish was rapid. Many Aymara at this turbulent time became laborers at mines and agricultural fields. In the subsequent colonial era, the Aymara were organized into eleven tribes which were the Canchi, Caranga, Charca, Colla, Collagua, Collahuaya, Omasuyo, Lupaca, Quillaca, Ubina, and Pacasa. Aymara used many of the agricultural and technological techniques from the Spanish like the use of plows, draft animals, wheat, barley, sheep, cattle, and plank boats for fishing, However, the Aymara still engaged in traditional occupations like raising Alpacas, growing native crops, and net fishing.[6]

In response to colonial exploitation by the Spanish and elite in the fields of agriculture, mining, coca harvesting, domestic work and more the Aymara (along with others) staged a rebellion in 1629. This was followed by a more significant uprising mostly by Aymaras in 1780 in which the Aymara almost captured the city of La Paz and many Spaniards were killed. This rebellion would be put down by the Spanish two years later. However uprisings would continue to occur against Spanish rule intermittently until Peruvian independence in 1821.[6]

The major reforms caused by the Bolivian Revolution of 1952 resulted in the Aymara being more integrated into mainstream Bolivian society. This also caused many Aymara to become severed or not affiliated with their native communities any longer. Most Bolivian Aymara today engage in farming, construction, mining, and working in factories though a growing number are now in professional work. The Aymara language (along with Quechua) are now official languages in Bolivia and there has been a rise of programs to assist the Aymara and their native lands.[6]

Linguists have learned that Aymara was once spoken much further north, at least as far north as central parts of Peru. Most Andean linguists believe that it is likely that the Aymara originated or coalesced as a people in this area (see 'Geography' below).

The Aymaras overran and displaced the Uru, an older population from the Lake Titicaca and Lake Poopó regions. The Uru lived in this area as recently as the 1930s.[7]

Geography

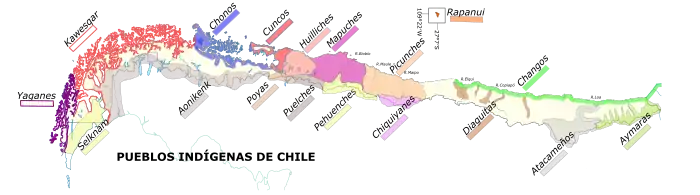

.png.webp)

Most present-day Aymara-speakers live in the Lake Titicaca basin, a territory from Lake Titicaca through the Desaguadero River and into Lake Poopo (Oruro, Bolivia) also known as the Altiplano. They are concentrated south of the lake. The capital of the ancient Aymara civilization is unknown. According to research by Cornell University anthropologist John Murra, there were at least seven different kingdoms. The capital of the Lupaqa Kingdom may be the city of Chucuito, located on the shore of Lake Titicaca.

The present urban center of the Aymara region may be El Alto, a 750,000-person city near the Bolivian capital, La Paz. For most of the 20th century, the center of cosmopolitan Aymara culture might've been Chuquiago Marka (La Paz). Bolivia's capital might have had moved from Sucre to La Paz during the government of General Pando (died in 1917) and during the Bolivian Civil War.

Culture

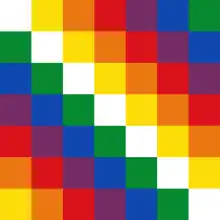

The Aymara flag is known as the Wiphala; it consists of seven colors quilted together with diagonal stripes.

The native language of the Aymaras is Aymara. Many of Aymaras speak Spanish as a second or first language, when it is the predominant language in the areas where they live. The Aymara language has one surviving relative, spoken by a small, isolated group of about 1,000 people far to the north in the mountains inland from Lima in Central Peru (in and around the village of Tupe, Yauyos province, Lima department). This language, whose two varieties are known as Jaqaru and Kawki,[8] is of the same family as Aymara. Some linguists refer to this language as 'Central Aymara.' 'Southern Aymara' is the language spoken most widely and is spoken by people of the Titicaca region.

Most of contemporary Aymaran urban culture was developed in the working-class Aymara neighborhoods of La Paz, such as Chijini and others. Both Quechua and Aymara women in Peru and Bolivia took up the style of wearing bowler hats since the 1920s. According to legend, a shipment of bowler hats was sent from Europe to Bolivia via Peru for use by Europeans working on railroad construction. When the hats were found to be too small, they were given to the indigenous peoples.[9] The luxurious, elegant and cosmopolitan Aymara Chola dress, which is an icon of Bolivia (bowler hat, aguayo, heavy pollera, skirts, boots, jewellery, etc.) began and evolved in La Paz. It is an urban tradition of dress. This style of dress has become part of ethnic identification by Aymara women. Many Aymara live and work as campesinos in the surrounding Altiplano.

The Aymaras have grown and chewed coca plants for centuries, using its leaves in traditional medicine as well as in ritual offerings to the father god Inti (Sun) and the mother goddess Pachamama (Earth). During the last century, there has been conflict with state authorities over this plant during drug wars; the officials have carried out coca eradication to prevent the extraction and isolation of the drug cocaine. But, the ritual use of coca has a central role in the indigenous religions of both the Aymaras and the Quechuas. Coca is used in the ritual curing ceremonies of the yatiri. Since the late 20th century, its ritual use has become a symbol of cultural identity.

Chairo is a traditional stew of the Aymaras. It is made of chuño (potato starch), onions, carrots, potatoes, white corn, beef and wheat kernels. It also contains herbs such as coriander and spices. It is native to the region of La Paz.

Religion and mythology

Most modern Aymara practice a syncretic form of Catholicism infused with natives practices and beliefs. Soon after the Spanish conquest, Jesuits and Dominican priests began to convert and proselytize among the Aymara. However, the Aymara continued to practice their native faith and only nominally accepted Christianity. Modern Aymara spirituality includes many syncretic beliefs like folk healing, divination, magic, and more. However, when it comes to the beliefs about the afterlife, the Aymara subscribe to a more standard view as found in traditional Christianity.[6]

In Aymara mythology llamas are important beings. The Heavenly Llama is said to drink water from the ocean and urinate it as rain.[10] According to Aymara eschatology llamas will return to the water springs and lagoons where they come from at the end of time.[10]

Politics

The Aymaras and other indigenous groups have formed numerous movements for greater independence or political power. These include the Tupac Katari Guerrilla Army, led by Felipe Quispe, and the Movement Towards Socialism, a political party organized by the Cocalero Movement and Evo Morales. These and other Aymara organizations have led political activism in Bolivia, including the 2003 Bolivian Gas War and the 2005 Bolivia protests.

Quispe has said that one of his group's goals is to establish an independent indigenous state. They have proposed the name Qullasuyu, after the eastern (and largely Aymara) region of the Inca empire, which covered the southeastern corner of present-day Peru and western Bolivia.

Evo Morales is an Aymara coca grower from the Chaparé region. His Movement Toward Socialism party has forged alliances with both rural indigenous groups and urban working classes to form a broad leftist coalition in Bolivia. Morales has run for president in several elections since the late 20th century, gaining increasing support. In 2005 he won a surprise victory, winning the largest majority vote since Bolivia returned to democracy. He is the first indigenous president of Bolivia. He is credited with the ousting of Bolivia's previous two presidents.

Aymaras themselves make significant distinctions between Bolivian and Chilean Aymaras with the aim of establishing by nationality whom to have say on local issues and who not.[5]

See also

- Bartolina Sisa

- Evo Morales

- Gregoria Apaza

- Jaime Escalante

- Katarismo

- Kimsa Chata

- Roberto Mamani Mamani, contemporary Aymara artist

- Elysia Crampton, Aymara musician

- Socialist Aymara Group

- Túpac Katari

- Wiphala

References

- "Censo de Población y Vivienda 2012 Bolivia Características de la Población". Instituto Nacional de Estadística, República de Bolivia. p. 29.

- "Perú: Perfil Sociodemográfico" (PDF). Instituto Nacional de Estadística e Informática. p. 214.

- "Síntesis de Resultados Censo 2017" (PDF). Instituto Nacional de Estadísticas, Santiago de Chile. p. 16.

- "Censo Nacional de Población, Hogares y Viviendas 2010: Resultados definitivos: Serie B No. 2: Tomo 1" (PDF) (in Spanish). INDEC. p. 281. Archived from the original (PDF) on 8 December 2015. Retrieved 5 December 2015.

- Vergara, Jorge Iván; Gundermann, Hans (2012). "Constitution and internal dynamics of the regional identitary in Tarapacá and Los Lagos, Chile". Chungara (in Spanish). University of Tarapacá. 44 (1): 115–134. doi:10.4067/s0717-73562012000100009.

- Skutsch, Carl, ed. (2005). Encyclopedia of the World's Minorities. New York: Routledge. p. 160. ISBN 1-57958-468-3.

- Aaron I. Naar, Los Hombres del Lago". Note: This documentary film tells about the smallest community of Uru-Muratos, Puñaca Tintamaria. Narrated by ex-leader Daniel Moricio Choque, the movie recounts the history of their community, customs, and current problems: their continuous poverty, lack of land and representation, the contamination of Lake Poopó, and the effects of global warming. See a 12-minute piece from the film on YouTube.

- Martha Hardman has long argued that Jaqaru and Kawki are two separate languages, but most other linguists consider them to be two closely related dialects.

- Pateman, Robert (2006). Bolivia (Cultures of the World, Second). p. 70. ISBN 9780761420668.

- Montecino Aguirre, Sonia (2015). "Llamas". Mitos de Chile: Enciclopedia de seres, apariciones y encantos (in Spanish). Catalonia. p. 415. ISBN 978-956-324-375-8.

Further reading

- Adelson, Laurie, and Arthur Tracht. Aymara Weavings: Ceremonial Textiles of Colonial and 19th Century Bolivia. [Washington, D.C.]: Smithsonian Institution Traveling Exhibition Service, 1983. ISBN 0-86528-022-3

- Buechler, Hans C. The Masked Media: Aymara Fiestas and Social Interaction in the Bolivian Highlands. Approaches to Semiotics, 59. The Hague: Mouton, 1980. ISBN 90-279-7777-1

- Buechler, Hans C., and Judith-Maria Buechler. The Bolivian Aymara. Case studies in cultural anthropology. New York: Holt, Rinehart and Winston, 1971. ISBN 0-03-081380-8

- Carter, William E. Aymara Communities and the Bolivian Agrarian Reform. Gainesville: University of Florida Press, 1964.

- Eagen, James. The Aymara of South America, First peoples. Minneapolis: Lerner Publications Co, 2002. ISBN 0-8225-4174-2

- Forbes, David. "On the Aymara Indians of Bolivia and Peru," The Journal of the Ethnological Society of London. Vol 2 (1870): 193-305.

- Kolata, Alan L. Valley of the Spirits: A Journey into the Lost Realm of the Aymara. New York: Wiley, 1996. ISBN 0-471-57507-0

- Hardman, Martha James. The Aymara Language in Its Social and Cultural Context: A Collection Essays on Aspects of Aymara Language and Culture. Gainesville: University Presses of Florida, 1981. ISBN 0-8130-0695-3

- Lewellen, Ted C. Peasants in Transition: The Changing Economy of the Peruvian Aymara : a General Systems Approach. Boulder, Colo: Westview Press, 1978. ISBN 0-89158-076-X

- Murra, John. "An Aymara Kingdom in 1567," Ethnohistory 15, no. 2 (1968) 115-151.

- Orta, Andrew. Catechizing Culture: Missionaries, Aymara, and the "New Evangelism". New York: Columbia University Press, 2004. ISBN 0-231-13068-6

- Rivera Cusicanqui, Silvia. Oppressed but Not Defeated: Peasant Struggles Among the Aymara and Qhechwa in Bolivia, 1900-1980. Geneva: United Nations Research Institute for Social Development, 1987.

- Tschopik, Harry. The Aymara of Chucuito, Peru. 1951.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Aymara people. |

- Aymara site in English

- Society: an essay

- Aymara worldview reflected in concept of time

- NGO Chakana

- Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). . Encyclopædia Britannica (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press.

- Aaron I. Naar, Los Hombres del Lago", a documentary film. It tells about Puñaca Tintamaria, the smallest community of Uru-Muratos. Narrated by the community's ex-leader, Daniel Moricio Choque, the movie recounts the history of the community, customs, and current problems: their poverty, lack of land and representation, the contamination of Lake Poopó, and the impact of global warming. See a 12-minute piece from the film on YouTube.