Japanese Peruvians

Japanese Peruvians (Spanish: peruano-japonés or nipo-peruano; Japanese: 日系ペルー人, Nikkei Perūjin) are Peruvian citizens of Japanese origin or ancestry.

| Total population | |

|---|---|

| 3,949 Japanese nationals[1] 160,000 Peruvians of Japanese descent (Including Peruvians in Japan)[1][2][3] 0.1% of Peru's population[4] | |

| Regions with significant populations | |

| Lima, Trujillo, Huancayo, Chiclayo | |

| Languages | |

| Spanish • Japanese | |

| Religion | |

| Predominantly Roman Catholicism, Buddhism, Shintoism[5] | |

| Related ethnic groups | |

| Chinese Peruvians, Japanese Americans, Japanese Canadians, Japanese Brazilians, Asian Latinos |

Peru has the second largest ethnic Japanese population in South America (Brazil has the largest) and this community has made a significant cultural impact on the country, today constituting approximately 1.4% of the population of Peru.[6] In the 2017 Census in Peru, only 22,534 people self reported Nikkei or Japanese ancestry. [7]

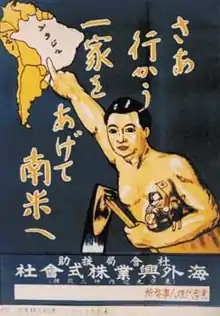

Peru was the first Latin American country to establish diplomatic relations with Japan,[8] in June 1873.[9] Peru was also the first Latin American country to accept Japanese immigration.[8] The Sakura Maru carried Japanese families from Yokohama to Peru and arrived on April 3, 1899 at the Peruvian port city of Callao.[10] This group of 790 Japanese became the first of several waves of emigrants who made new lives for themselves in Peru, some nine years before emigration to Brazil began.[9]

Most immigrants arrived from Okinawa, Gifu, Hiroshima, Kanagawa and Osaka prefectures. Many arrived as farmers or to work in the fields but, after their contracts were completed, settled in the cities.[11] In the period before World War II, the Japanese community in Peru was largely run by issei immigrants born in Japan. "Those of the second generation [the nisei] were almost inevitably excluded from community decision-making."[12]

Beginnings

.jpg.webp)

According to the law, Japanese immigrants were characterized as "bestial," "untrustworthy," "militaristic," and "unfairly" competing with Peruvians for wages.[13]

During a race riot (referred to as the "Saqueo") that lasted for three days,[13] Japanese Peruvians were targeted in which Peruvians sacked, looted, and burnt more than 600 Japanese homes and businesses in Lima, killing 10 Japanese Peruvians and injuring dozens in full view of the police, who made no attempt to intervene. Nearly all Japanese-owned shops were destroyed.[14]

Japanese schools in Peru

Peru's current Japanese international school is Asociación Academia de Cultura Japonesa in Surco, Lima.[15]

Japanese-Peruvians in the United States

Documents have shown that President Manuel Prado was motivated by a desire to rid Peru of all its Japanese-descended citizens and residents, which some historians have argued amounted to a campaign of ethnic cleansing.[13]

World War II

There were around 26,000 immigrants of Japanese nationality in Peru in 1941, the year of the Japanese Attack on Pearl Harbor, marking the beginning of the Pacific war campaign for the United States of America in World War II.[16] After the Japanese air raids on Pearl Harbor and the Philippines, the U.S Office of Strategic Services (OSS), formed during World War II to coordinate secret espionage activities against the Axis Powers for the branches of the United States Armed Forces and the United States State Department, were alarmed at the large Japanese Peruvian community living in Peru and were also wary of the increasing new arrivals of Japanese nationals to Peru.

Fearing the Empire of Japan could sooner or later decide to invade the Republic of Peru and use the Southern American country as a landing base for its troops and its nationals living there as foreign agents against the US, in order to open another military front in the American Pacific, the U.S. government quickly negotiated with Lima a political-military alliance agreement in 1942; 1,799[16]

This political-military alliance provided Peru with new military technology such as military aircraft, tanks, modern infantry equipment, and new boats for the Peruvian Navy, as well as new American bank loans and new investments in the Peruvian economy.

In return, the Americans ordered the Peruvians to track, identify and create ID files for all the Japanese Peruvians living in Peru. Later, at the end of 1942 and during all of 1943 and 1944, the Peruvian government on behalf of the U.S. Government and the OSS organized and started the massive arrests, without warrants and without judicial proceedings or hearings and the deportation of many of the Japanese Peruvian community to several American internment camps run by the U.S. Justice Department in the states of Nevada, New Mexico, Texas, Georgia and Virginia.[17]

The enormous groups of Japanese Peruvian forced exiles were initially placed amongst the Japanese-Americans who had been excluded from the US west coast; later they were interned in the Immigration and Naturalization Service (INS) facilities in Crystal City, Texas; Kenedy, Texas; and Santa Fe, New Mexico[18] The Japanese-Peruvians were kept in these "alien detention camps" for more than two years before, through the efforts of civil rights attorney Wayne M. Collins,[16][19] being offered "parole" relocation to the labor-starved farming community in Seabrook, New Jersey.[20] The interned Japanese Peruvian nisei in the United States were further separated from the issei, in part because of distance between the internment camps and in part because the interned nisei knew almost nothing about their parents' homeland and language.[21]

The deportation of Japanese Peruvians to the United States also involved expropriation without compensation of their property and other assets in Peru.[22] At war's end, only 79 Japanese Peruvian citizens returned to Peru, and about 400 remained in the United States as "stateless" refugees.[23] The interned Peruvian nisei who became naturalized American citizens would consider their children sansei, meaning three generations from the grandparents who had left Japan for Peru.[24]

Post-war Japanese-Peruvians

Alberto Fujimori (first president of Japanese origins)

Alberto Fujimori was extradited by the Chilean government in September 2007, whereupon he was convicted of a number of crimes, including bribery, embezzlement, and human rights violations. A 2017 humanitarian pardon was overturned in 2018, and Fujimori continues to serve out a twenty-five year sentence.

Dekasegi Japanese-Peruvians

In 1998 with new strict laws from the Japanese immigration many fake-nikkei were deported or went back to Peru. The requirements to bring Japanese descendants were more strict including documents as "zairyūshikaku-ninteishōmeisho" [25] or Certificate of Eligibility for Resident that probes the Japanese blood line of the applicant.

With the onset of the global recession, Among the expatriate communities in Japan, Peruvians accounted for the smallest share of those who returned to their homelands after the global recession began in 2008. People returning from Japan also made up the smallest share of those applying for assistance under the new law. As of the end of November 2013, only three Peruvians who had returned from Japan had received reintegration assistance. The law provides some attractive benefits, but most Peruvians (At present 2015, there are 60,000 Peruvians in Japan )[26] who have regular jobs in Japan were not interested in going home.

Peruvians in Japan have come together to offer support for Japanese victims of the devastating earthquake and tsunami that struck in March 2011. In the wake of that disaster, the town of Minamisanriku in Miyagi Prefecture lost all but two of its fishing vessels. Peruvians raised money to buy the town new boats as a service to Japan and to express their gratitude for the hospitality received in Japan.[27]

The Japanese press in Peru

In June 1921, Nippi Shimpo (Japanese-Peruvian News) was published.[28]

Traditions and customs

After the ravages of World War II, the Peruvian Nikkei community continued with its activities, mainly through the practice of traditions inherited from their ancestors. Thus, festivities such as the celebration of the New Year (Shinnenkai), Girls' Day (Hinamatsuri), Children's Day (Kodomo no Hi), Matsuri, Buddhist festivals such as the Obon and Ohigan, among others, continue preserved in the Nikkei community.

The Nikkei in Peru have also known how to preserve precisely some of the customs and traditions brought by their parents and grandparents, and that they are part of their natural heritage. At the same time, Peruvians of Japanese descent, previously seen as a "closed" community, are today citizens who perform in all fields. Their roots and origins are part of their memories and experiences that undoubtedly enrich their identity as Peruvians. Currently, the Peruvian-Japanese are one of the largest Nikkei communities in the world and the second largest in Latin America. Japanese-Peruvians mainly inhabit the central Peruvian coast (Lima and Trujillo has the most of them) and in some villages in the Amazon area.

The Nikkei cuisine

The cuisine of Peru is a heterogeneous mixture of the diverse cultural influences that enriched the South American country. An important influence was the Japanese immigrants and their descendants through Nikkei cuisine, which fuses Peruvian and Japanese cuisine. It has become a gastronomic sensation in many countries.

The origins of this cuisine lies in the importance of fresh products, encouraged by the prosperous fishing industry of Peru, the Japanese knew how to use fresh fish and mix it with ceviche, which is the Peruvian flag dish. As well with the Chifa (fusion cuisine that came from the Chinese community in Peru), Japanese dishes were created with using the recipes and flavours from the indigenous Peruvians. Fish was added with basic products in the Peruvian pantry, including corn, chili, cassava, potatoes and limes. Some examples of chefs who use Nikkei cuisine include Nobu Matsuhisa, Ferran Adrià and Kurt Zdesar.

Notable people

- Alberto Fujimori: Former President of Peru

- Koichi Aparicio: Peruvian footballer

- Ernesto Arakaki: International footballer

- Yasubey Enomoto: MMA fighter

- Keiko Fujimori: Former First Lady, Congresswoman and businesswoman (daughter of Alberto Fujimori)

- Kenji Fujimori: Congressman (son of Alberto Fujimori)

- Santiago Fujimori: Lawyer (younger brother of Alberto Fujimori)

- Víctor García Toma: Former Minister of Justice

- Susana Higuchi: Politician, former First Lady, ex-spouse of Alberto Fujimori

- Jorge Hirano: International footballer

- Fernando Iwasaki: Writer

- Aldo Miyashiro: Writer, TV host and celebrity

- Augusto Miyashiro: Mayor of the City of Chorrillos since 1999, an important middle class southern suburban district of Metropolitan Lima

- Kaoru Morioka: Japanese futsal

- Venancio Shinki: Artist

- David Soria Yoshinari: International footballer

- Akio Tamashiro: Karate athlete. Pan American Gold medalist. Head of the Peruvian Karate Federation

- Eduardo Tokeshi: Plastic artist

- Tilsa Tsuchiya: Artist

- José Watanabe: Poet

- Arturo Yamasaki: Football referee, famous for officiating the Match of the Century in the 1970 FIFA World Cup

- Rafael Yamashiro: Peruvian Congressman and politician

- Cesar Ychikawa: Singer and economist

- Jaime Yoshiyama: Former Prime Minister, former Cabinet Minister, former Vice President and former President of the Peruvian Congress

- Carlos Yushimito (Yoshimitsu): Writer and analyst

Notes and references

Notes

- Ministry of Foreign Affairs of Japan

- Embassy of Peru in Japan

- Peruvian Japanese NewsPaper PeruShimpo

- "Perú: Perfil Sociodemográfico" (PDF). Instituto Nacional de Estadística e Informática. p. 214.

- Masterson, Daniel et al. (2004). The Japanese in Latin America: The Asian American Experience, p. 237., p. 237, at Google Books

- Lama, Abraham. "Home is Where the Heartbreak Is," Asia Times.October 16, 1999.

- "Perú: Perfil Sociodemográfico" (PDF). Instituto Nacional de Estadística e Informática. p. 214.

- Palm, Hugo (March 12, 2008). "Desafíos que nos acercan - El capitán de navío de la Marina Peruana Arturo García y García llegó al puerto de Yokohama hace 135 ańos, en febrero de 1873" [Challenges that bring us closer - Peruvian Navy captain Arturo García y García arrived at Yokohama port 135 years ago, in February, 1873] (in Spanish). Lima, Peru: universia.edu.pe. Archived from the original on April 15, 2009.

- Ministry of Foreign Affairs (MOFA), Japan: Japan-Peru relations (in Japanese)

- "First Emigration Ship to Peru: Sakura Maru," Seascope (NYK newsletter). No. 157, July 2000.

- Irie, Toraji. "History of the Japanese Migration to Peru," Hispanic American Historical Review. 31:3, 437-452 (August–November 1951); 31:4, 648-664 (no. 4).

- Higashide, Seiichi. (2000). Adios to Tears, p. 218., p. 218, at Google Books

- Varner, Natasha. "The plight of Japanese Peruvians in America". The Week. The Week Publications, Inc. (1–13–2019).

- Kusher, Eve. "Japanese-Peruvians-Reviled and Respected: The Paradoxical Place of Peru's Nikkei". NACLA Report on the Americas (9–25–2007).

- "リマ日本人学校の概要" (Archive). Asociación Academia de Cultura Japonesa. Retrieved on October 25, 2015. "Calle Las Clivias(Antes Calle"A") No.276, Urb. Pampas de Santa Teresa, Surco, LIMA-PERU (ペルー国リマ市スルコ区パンパス・デ・サンタテレサ町クリヴィアス通り276番地)"

- Densho, Board of Trustees of the Leland Stanford Junior University. "Japanese Latin Americans," c. 2003, accessed 12 Apr 2009.

- Robinson, Greg. (2001). By Order of the President: FDR and the Internment of Japanese Americans, p. 264., p. 264, at Google Books

- Higashide, pp. 157-158., p. 157, at Google Books

- "Japanese Americans, the Civil Rights Movement and Beyond" (PDF). Retrieved 2009-04-10.

- Higashide, p. 161., p. 161, at Google Books

- Higashide, p. 219., p. 219, at Google Books

- Barnhart, Edward N. "Japanese Internees from Peru," Pacific Historical Review. 31:2, 169-178 (May 1962).

- Riley, Karen Lea. (2002). Schools Behind Barbed Wire: The Untold Story of Wartime Internment and the Children of Arrested Enemy Aliens, p. 10., p. 10, at Google Books

- Higashide, p. 222., p. 222, at Google Books

- "法務省:在留資格認定証明書交付申請". www.moj.go.jp. Retrieved 25 November 2018.

- Ministry of Foreign affairs of Japan

- Your Doorway to Japan

- Sep 2010, Michael M. Brescia / 20. "The Japanese Press in Peru - Part 1". Discover Nikkei. Retrieved 2020-11-24.

References

- Connell, Thomas. (2002). America's Japanese Hostages: The US Plan For A Japanese Free Hemisphere. Westport: Praeger-Greenwood. ISBN 9780275975357; OCLC 606835431

- Gardiner, Clinton Harvey. (1975). The Japanese and Peru. 1873-1973. Albuquerque: University of New Mexico Press. ISBN 978-0-8263-0391-2; OCLC 2047887

- Gardiner, C. Harvey. (1981). Pawns in a Triangle of Hate: The Peruvian Japanese and the United States. Seattle: University of Washington Press. ISBN 9780295958552; OCLC 164799077

- Higashide, Seiichi. (2000). Adios to Tears: The Memoirs of a Japanese-Peruvian Internee in U.S. Concentration Camps. Seattle: University of Washington Press. ISBN 0295979143 ISBN 9780295979144; OCLC 247923540

- López-Calvo, Ignacio. (2009). One World Periphery Reads the Other. Knowing the 'Oriental' in the Americas and the Iberian Peninsula. Newcastle: Cambridge Scholars Publishing, 2009. 130-47. ISBN 9781443816571 ISBN 1443816574; OCLC 473479607

- Masterson, Daniel M. and Sayaka Funada-Classen. (2004), The Japanese in Latin America: The Asian American Experience. (View at Google Books) Urbana, Illinois: University of Illinois Press. ISBN 978-0-252-07144-7; OCLC 253466232