Backgammon

Backgammon is one of the oldest known board games. Its history can be traced back nearly 5,000 years to archaeological discoveries in Mesopotamia.[2][3][4][5] It is a two-player game where each player has fifteen pieces (checkers or men) that move between twenty-four triangles (points) according to the roll of two dice. The objective of the game is to be first to bear off, i.e. move all fifteen checkers off the board. Backgammon is a member of the tables family, one of the oldest classes of board games.

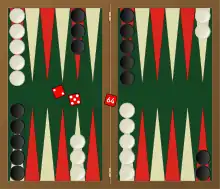

A backgammon set, consisting of a board, two sets of 15 checkers, two pairs of dice, a doubling cube, and dice cups | |

| Years active | Approximately 5,000 years ago in the Middle East to present[1] |

|---|---|

| Genre(s) | |

| Players | 2 |

| Setup time | 10–30 seconds |

| Playing time | 5–60 minutes |

| Random chance | Medium (dice rolling) |

| Age range | 5+ |

| Skill(s) required | |

Backgammon involves a combination of strategy and luck (from rolling dice). While the dice may determine the outcome of a single game, the better player will accumulate the better record over a series of many games. With each roll of the dice, players must choose from numerous options for moving their checkers and anticipate possible counter-moves by the opponent. The optional use of a doubling cube allows players to raise the stakes during the game.

Like chess, backgammon has been studied with great interest by computer scientists. Owing to this research, backgammon software such as TD-Gammon has been developed that is capable of beating world-class human players.

Rules

Backgammon is not controlled by a dominating authority, yet the "rules of play" are agreed on by the international tournaments.[6]

Backgammon playing pieces may be termed checkers, draughts, stones, men, counters, pawns, discs, pips, chips, or nips.[7][8]

The objective is for players to remove (bear off) all their checkers from the board before their opponent can do the same. As the playing time for each individual game is short, it is often played in matches where victory is awarded to the first player to reach a certain number of points.

Setup

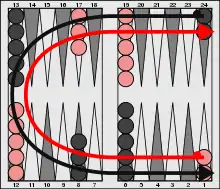

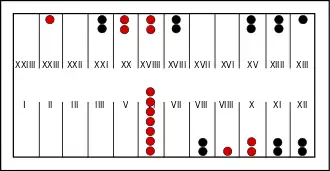

Each side of the board has a track of 12 long triangles, called points. The points form a continuous track in the shape of a horseshoe, and are numbered from 1 to 24. In the most commonly used setup, each player begins with fifteen chips, two are placed on their 24-point, three on their 8-point, and five each on their 13-point and their 6-point. The two players move their chips in opposing directions, from the 24-point towards the 1-point.[9]

Points 1 through 6 are called the home board or inner board, and points 7 through 12 are called the outer board. The 7-point is referred to as the bar point, and the 13-point as the midpoint. Usually the 5-point for each player is called the "golden point".[9][10]

Movement

To start the game, each player rolls one die, and the player with the higher number moves first using the numbers shown on both dice.[11] If the players roll the same number, they must roll again. Both dice must land completely flat on the right-hand side of the gameboard. The players then take alternate turns, rolling two dice at the beginning of each turn.[9][10]

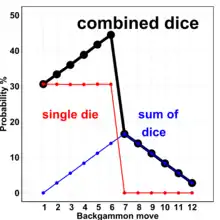

After rolling the dice, players must, if possible, move their checkers according to the number shown on each die. For example, if the player rolls a 6 and a 3 (denoted as "6-3"), the player must move one checker six points forward, and another or the same checker three points forward. The same checker may be moved twice, as long as the two moves can be made separately and legally: six and then three, or three and then six. If a player rolls two of the same number, called doubles, that player must play each die twice. For example, a roll of 5-5 allows the player to make four moves of five spaces each. On any roll, a player must move according to the numbers on both dice if it is at all possible to do so. If one or both numbers do not allow a legal move, the player forfeits that portion of the roll and the turn ends. If moves can be made according to either one die or the other, but not both, the higher number must be used. If one die is unable to be moved, but such a move is made possible by the moving of the other die, that move is compulsory.

In the course of a move, a checker may land on any point that is unoccupied or is occupied by one or more of the player's own checkers. It may also land on a point occupied by exactly one opposing checker, or "blot". In this case, the blot has been "hit" and is placed in the middle of the board on the bar that divides the two sides of the playing surface. A checker may never land on a point occupied by two or more opposing checkers; thus, no point is ever occupied by checkers from both players simultaneously.[9][10] There is no limit to the number of checkers that can occupy a point at any given time.

Checkers placed on the bar must re-enter the game through the opponent's home board before any other move can be made. A roll of 1 allows the checker to enter on the 24-point (opponent's 1), a roll of 2 on the 23-point (opponent's 2), and so forth, up to a roll of 6 allowing entry on the 19-point (opponent's 6). Checkers may not enter on a point occupied by two or more opposing checkers. Checkers can enter on unoccupied points, or on points occupied by a single opposing checker; in the latter case, the single checker is hit and placed on the bar. More than one checker can be on the bar at a time. A player may not move any other checkers until all checkers on the bar belonging to that player have re-entered the board.[9][10] If a player has checkers on the bar, but rolls a combination that does not allow any of those checkers to re-enter, the player does not move. If the opponent's home board is completely "closed" (i.e. all six points are each occupied by two or more checkers), there is no roll that will allow a player to enter a checker from the bar, and that player stops rolling and playing until at least one point becomes open (occupied by one or zero checkers) due to the opponent's moves.

Bearing off

When all of a player's checkers are in that player's home board, that player may start removing them; this is called "bearing off". A roll of 1 may be used to bear off a checker from the 1-point, a 2 from the 2-point, and so on. If all of a player's checkers are on points lower than the number showing on a particular die, the player must use that die to bear off one checker from the highest occupied point.[9][10] For example, if a player rolls a 6 and a 5, but has no checkers on the 6-point and two on the 5-point, then the 6 and the 5 must be used to bear off the two checkers from the 5-point. When bearing off, a player may also move a lower die roll before the higher even if that means the full value of the higher die is not fully utilized. For example, if a player has exactly one checker remaining on the 6-point, and rolls a 6 and a 1, the player may move the 6-point checker one place to the 5-point with the lower die roll of 1, and then bear that checker off the 5-point using the die roll of 6; this is sometimes useful tactically. As before, if there is a way to use all moves showing on the dice by moving checkers within the home board or by bearing them off, the player must do so. If a player's checker is hit while in the process of bearing off, that player may not bear off any others until it has been re-entered into the game and moved into the player's home board, according to the normal movement rules.

The first player to bear off all fifteen of their own checkers wins the game. If the opponent has not yet borne off any checkers when the game ends, the winner scores a gammon, which counts for double stakes. If the opponent has not yet borne off any checkers and has some on the bar or in the winner's home board, the winner scores a backgammon, which counts for triple stakes.[9][10]

Doubling cube

To speed up match play and to provide an added dimension for strategy, a doubling cube is usually used. The doubling cube is not a die to be rolled, but rather a marker, with the numbers 2, 4, 8, 16, 32, and 64 inscribed on its sides to denote the current stake. At the start of each game, the doubling cube is placed on the midpoint of the bar with the number 64 showing; the cube is then said to be "centered, on 1". When the cube is centered, either player may start their turn by proposing that the game be played for twice the current stakes. Their opponent must either accept ("take") the doubled stakes or resign ("drop") the game immediately.

Whenever a player accepts doubled stakes, the cube is placed on their side of the board with the corresponding power of two facing upward, to indicate that the right to re-double belongs exclusively to that player.[9][10] If the opponent drops the doubled stakes, they lose the game at the current value of the doubling cube. For instance, if the cube showed the number 2 and a player wanted to redouble the stakes to put it at 4, the opponent choosing to drop the redouble would lose two, or twice the original stake.

There is no limit on the number of redoubles. Although 64 is the highest number depicted on the doubling cube, the stakes may rise to 128, 256, and so on. In money games, a player is often permitted to "beaver" when offered the cube, doubling the value of the game again, while retaining possession of the cube.[12]

A variant of the doubling cube "beaver" is the "raccoon". Players who doubled their opponent, seeing the opponent beaver the cube, may in turn then double the stakes once again ("raccoon") as part of that cube phase before any dice are rolled. The opponent retains the doubling cube. An example of a "raccoon" is the following: White doubles Black to 2 points, Black accepts then beavers the cube to 4 points; White, confident of a win, raccoons the cube to 8 points, while Black retains the cube. Such a move adds greatly to the risk of having to face the doubling cube coming back at 8 times its original value when first doubling the opponent (offered at 2 points, counter offered at 16 points) should the luck of the dice change.

Some players may opt to invoke the "Murphy rule" or the "automatic double rule". If both opponents roll the same opening number, the doubling cube is incremented on each occasion yet remains in the middle of the board, available to either player. The Murphy rule may be invoked with a maximum number of automatic doubles allowed and that limit is agreed to prior to a game or match commencing. When a player decides to double the opponent, the value is then a double of whatever face value is shown (e.g. if two automatic doubles have occurred putting the cube up to 4, the first in-game double will be for 8 points). The Murphy rule is not an official rule in backgammon and is rarely, if ever, seen in use at officially sanctioned tournaments.

The "Jacoby rule", named after Oswald Jacoby, allows gammons and backgammons to count for their respective double and triple values only if the cube has already been offered and accepted. This encourages a player with a large lead to double, possibly ending the game, rather than to play it to conclusion hoping for a gammon or backgammon. The Jacoby rule is widely used in money play but is not used in match play.[13]

The "Crawford rule", named after John R. Crawford, is designed to make match play more equitable for the player in the lead. If a player is one point away from winning a match, that player's opponent will always want to double as early as possible in order to catch up. Whether the game is worth one point or two, the trailing player must win to continue the match. To balance the situation, the Crawford rule requires that when a player first reaches a score one point short of winning, neither player may use the doubling cube for the following game, called the "Crawford game". After the Crawford game, normal use of the doubling cube resumes. The Crawford rule is routinely used in tournament match play.[13] It is possible for a Crawford game to never occur in a match.

If the Crawford rule is in effect, then another option is the "Holland rule", named after Tim Holland, which stipulates that after the Crawford game, a player cannot double until after at least two rolls have been played by each side. It was common in tournament play in the 1980s, but is now rarely used.[14]

Variants

There are many variants of standard backgammon rules. Some are played primarily throughout one geographic region, and others add new tactical elements to the game. Variants commonly alter the starting position, restrict certain moves, or assign special value to certain dice rolls, but in some geographic regions even the rules and directions of the checkers' movement change, rendering the game fundamentally different.

Acey-deucey is a variant of backgammon in which players start with no checkers on the board, and must bear them on at the beginning of the game. The roll of 1-2 is given special consideration, allowing the player, after moving the 1 and the 2, to select any desired doubles move. A player also receives an extra turn after a roll of 1-2 or of doubles.[15]

Hypergammon is a variant of backgammon in which players have only three checkers on the board, starting with one each on the 24, 23 and 22 points. The game has been strongly solved, meaning that exact equities are available for all 32 million possible positions.[16][17]

Nard is a traditional variant from Persia in which basic rules are almost the same except that even a single piece is "safe". All 15 pieces start on the 24th wedge.

Nackgammon is a variant of backgammon invented by Nick "Nack" Ballard[18] in which players start with one less checker on the 6-point and midpoint and two checkers on the 23-point.[17][19]

Russian backgammon is a variant described in 1895 as: "...much in vogue in Russia, Germany, and other parts of the Continent...".[20] Players start with no checkers on the board, and both players move in the same direction to bear off in a common home board. In this variant, doubles are more powerful: four moves are played as in standard backgammon, followed by four moves according to the difference of the dice value from 7, and then the player has another turn (with the caveat that the turn ends if any portion of it cannot be completed).[21]

Gul bara and Tapa are also variants of the game popular in southeastern Europe and Turkey. The play will iterate among Backgammon, Gul Bara, and Tapa until one of the players reaches a score of 7 or 5.

Coan ki is an ancient Chinese board game that is very similar.

Plakoto, Fevga and Portes are three versions of backgammon played in Greece. Together, the three are referred to as Tavli.[22]

Misere (backgammon to lose) is a variant of backgammon in which the objective is to lose the game.[23]

Tavla is a Turkish variation.

Tabla is a Bulgarian variant of Backgammon, played without the doubling cube.[24]

Other minor variants to the standard game are common among casual players in certain regions. For instance, only allowing a maximum of five checkers on any point (Britain)[25] or disallowing "hit-and-run" in the home board (Middle East).[26][27]

Strategy and tactics

Backgammon has an established opening theory, although it is less detailed than that of chess. The tree of positions expands rapidly because of the number of possible dice rolls and the moves available on each turn. Recent computer analysis has offered more insight on opening plays, but the midgame is reached quickly. After the opening, backgammon players frequently rely on some established general strategies, combining and switching among them to adapt to the changing conditions of a game.

A blot has the highest probability of being hit when it is 6 points away from an opponent's checker (see picture). Strategies can derive from that. The most direct one is simply to avoid being hit, trapped, or held in a stand-off. A "running game" describes a strategy of moving as quickly as possible around the board, and is most successful when a player is already ahead in the race.[28] When this fails, one may opt for a "holding game", maintaining control of a point on one's opponent's side of the board, called an anchor. As the game progresses, this player may gain an advantage by hitting an opponent's blot from the anchor, or by rolling large doubles that allow the checkers to escape into a running game.[28]

The "priming game" involves building a wall of checkers, called a prime, covering a number of consecutive points. This obstructs opposing checkers that are behind the prime. A checker trapped behind a six-point prime cannot escape until the prime is broken.[28] A particularly successful priming effort may lead to a "blitz", which is a strategy of covering the entire home board as quickly as possible while keeping one's opponent on the bar. Because the opponent has difficulty re-entering from the bar or escaping, a player can quickly gain a running advantage and win the game, often with a gammon.[9]

A "backgame" is a strategy that involves holding two or more anchors in an opponent's home board while being substantially behind in the race.[29] The anchors obstruct the opponent's checkers and create opportunities to hit them as they move home. The backgame is generally used only to salvage a game wherein a player is already significantly behind. Using a backgame as an initial strategy is usually unsuccessful.[9][28]

"Duplication" refers to the placement of checkers such that one's opponent needs the same dice rolls to achieve different goals. For example, players may position all of their blots in such a way that the opponent must roll a 2 in order to hit any of them, reducing the probability of being hit more than once.[9][28] "Diversification" refers to a complementary tactic of placing one's own checkers in such a way that more numbers are useful.[28]

Many positions require a measurement of a player's standing in the race, for example, in making a doubling cube decision, or in determining whether to run home and begin bearing off. The minimum total of pips needed to move a player's checkers around and off the board is called the "pip count". The difference between the two players' pip counts is frequently used as a measure of the leader's racing advantage. Players often use mental calculation techniques to determine pip counts in live play.[28]

Backgammon is played in two principal variations, "money" and "match" play. Money play means that every point counts evenly and every game stands alone, whether money is actually being wagered or not. "Match" play means that the players play until one side scores (or exceeds) a certain number of points. The format has a significant effect on strategy. In a match, the objective is not to win the maximum possible number of points, but rather to simply reach the score needed to win the match. For example, a player leading a 9-point match by a score of 7–5 would be very reluctant to turn the doubling cube, as their opponent could take and make a costless redouble to 4, placing the entire outcome of the match on the current game. Conversely, the trailing player would double very aggressively, particularly if they have chances to win a gammon in the current game. In money play, the theoretically correct checker play and cube action would never vary based on the score.

In 1975, Emmet Keeler and Joel Spencer considered the question of when to double or accept a double using an idealized version of backgammon. In their idealized version, the probability of winning varies randomly over time by Brownian motion, and there are no gammons or backgammons. They showed that the optimal time to offer a double was when the probability of winning reached 80%, and it is wise to accept a double only if the probability of winning is at least 20%. As their assumptions do not correspond perfectly to the real game, actual doubling strategy may vary, but the 80% number still provides a possible rule of thumb.[30]

Cheating

To reduce the possibility of cheating, most good quality backgammon sets use precision dice and a dice cup.[31] This reduces the likelihood of loaded dice being used, which is the main way of cheating in face-to-face play.[32] A common method of cheating online is the use of a computer program to find the optimal move on each turn; to combat this, many online sites use move-comparison software that identifies when a player's moves resemble those of a backgammon program. Online cheating has therefore become extremely difficult.[31]

Social and competitive play

Legality

Early Muslim scholars forbade backgammon.[33] The prohibition was based on sayings attributed to the Prophet Muhammad regarding gambling in general and backgammon in particular, such as: "Whoever plays backgammon it is as if he puts his hand in the pork and pig's blood."[34] Contemporary Ayatollah Ali al-Sistani of Iraq, one of the prominent religious leaders of Shia Muslims, issued a ruling that chess (and by implication backgammon) "is absolutely forbidden even without placing a bet".[35]

In State of Oregon v. Barr, a 1982 court case pivotal to the continued widespread organised playing of backgammon in the US, the State argued that backgammon is a game of chance and that it was therefore subject to Oregon's stringent gambling laws. Paul Magriel was a key witness for the defence, contradicting Roger Nelson, the expert prosecution witness, by saying, "Game theory, however, really applies to games with imperfect knowledge, where something is concealed, such as poker. Backgammon is not such a game. Everything is in front of you. The person who uses that information in the most effective manner will win." After the closing arguments, Judge Stephen S. Walker concluded that backgammon is a game of skill, not a game of chance, and found the defendant, backgammon tournament director Ted Barr, not guilty of promoting gambling.[36]

Club and tournament play

Enthusiasts have formed clubs for social play of backgammon. Local clubs may hold informal gatherings, with members meeting at cafés and bars in the evening to play and converse.[37][38] A few clubs offer additional services, maintaining their own facilities or offering computer analysis of troublesome plays.[39] Around 2003, some club leaders noticed a growth of interest in backgammon, and attributed it to the game's popularity on the Internet.[40]

A backgammon chouette permits three or more players to participate in a single game, often for money. One player competes against a team of all the other participants, and positions rotate after each game. Chouette play often permits the use of multiple doubling cubes.[9]

Backgammon clubs may also organize tournaments. Large club tournaments sometimes draw competitors from other regions, with final matches viewed by hundreds of spectators.[41] The top players at regional tournaments often compete in major national and international championships. Winners at major tournaments may receive prizes of tens of thousands of dollars.[42]

Starting in January 2018, tournament directors began awarding GammonPoints,[43] a free points registry for tournament directors and players, with GammonPoint awards based on the number of players and strength of field.

International competition

The first world championship competition in backgammon was held in Las Vegas, Nevada in 1967. Tim Holland was declared the winner that year and at the tournament the following year. For unknown reasons, there was no championship in 1970, but in 1971, Tim Holland again won the title. The competition remained in Las Vegas until 1975, when it moved to Paradise Island in the Bahamas. The years 1976, 1977 & 1978 saw "dual" World Championships, one in the Bahamas attended by the Americans, and the European Open Championships in Monte Carlo with mostly European players. In 1979, Lewis Deyong, who had promoted the Bahamas World Championship for the prior three years, suggested that the two events be combined.[44] Monte Carlo was universally acknowledged as the site of the World Backgammon Championship and has remained as such for thirty years.[45] The Monte Carlo tournament draws hundreds of players and spectators, and is played over the course of a week.[42]

By the 21st century, the largest international tournaments had established the basis of a tour for top professional players. Major tournaments are held yearly worldwide. PartyGaming sponsored the first World Series of Backgammon in 2006 from Cannes and later the "Backgammon Million" tournament held in the Bahamas in January 2007 with a prize pool of one million dollars, the largest for any tournament to date.[46] In 2008, the World Series of Backgammon ran the world's largest international events in London, the UK Masters, the biggest tournament ever held in the UK with 128 international class players; the Nordic Open, which instantly became the largest in the world with around 500 players in all flights and 153 in the championship, and Cannes, which hosted the Riviera Cup, the traditional follow-up tournament to the World Championships. Cannes also hosted the WSOB championship, the WSOB finale, which saw 16 players play three-point shootout matches for €160,000. The event was recorded for television in Europe and aired on Eurosport.

The World Backgammon Association (WBA)[47] has been holding the biggest backgammon tour on the circuit since 2007, the "European Backgammon Tour"[48] (EBGT). In 2011, the WBA collaborated with the online backgammon provider Play65 for the 2011 season of the European Backgammon Tour and with "Betfair" in 2012. The 2013 season of the European Backgammon Tour featured 11 stops and 19 qualified players competing for €19,000 in a grand finale in Lefkosa, Northern Cyprus.

Gambling

When backgammon is played for money, the most common arrangement is to assign a monetary value to each point, and to play to a certain score, or until either player chooses to stop. The stakes are raised by gammons, backgammons, and use of the doubling cube. Backgammon is sometimes available in casinos. Before the commercialization of artificial neural network programs, proposition bets on specific positions were very common among backgammon players and gamblers.[49] As with most gambling games, successful play requires a combination of luck and skill, as a single dice roll can sometimes significantly change the outcome of the game.[28]

Software

The game is included in Clubhouse Games: 51 Worldwide Classics for the Nintendo Switch, a collection of tabletop games.[50]

Internet play

Backgammon software has been developed not only to play and analyze games, but also to facilitate play between humans over the internet. Dice rolls are provided by random or pseudorandom number generators. Real-time online play began with the First Internet Backgammon Server in July 1992,[51][52] but there are now a range of options,[53] many of which are commercial.

Play and analysis

Backgammon has been studied considerably by computer scientists. Neural networks and other approaches have offered significant advances to software for gameplay and analysis.

The first strong computer opponent was BKG 9.8. It was written by Hans Berliner in the late 1970s on a DEC PDP-10 as an experiment in evaluating board game positions. Early versions of BKG played badly even against poor players, but Berliner noticed that its critical mistakes were always at transitional phases in the game. He applied principles of fuzzy logic to improve its play between phases, and by July 1979, BKG 9.8 was strong enough to play against the reigning world champion Luigi Villa. It won the match 7–1, becoming the first computer program to defeat a world champion in any board game. Berliner stated that the victory was largely a matter of luck, as the computer received more favorable dice rolls.[54]

In the late 1980s, backgammon programmers found more success with an approach based on artificial neural networks. TD-Gammon, developed by Gerald Tesauro of IBM, was the first of these programs to play near the expert level. Its neural network was trained using temporal difference learning applied to data generated from self-play.[55] According to assessments by Bill Robertie and Kit Woolsey, TD-Gammon's play was at or above the level of the top human players in the world.[55] Woolsey said of the program that "There is no question in my mind that its positional judgment is far better than mine."[55]

Tesauro proposed using rollout analysis to compare the performance of computer algorithms against human players.[16] In this method, a Monte-Carlo evaluation of positions is conducted (typically thousands of trials) where different random dice sequences are simulated. The rollout score of the human (or the computer) is the difference of the average game results by following the selected move versus following the best move, then averaged for the entire set of taken moves.

Neural network research has resulted in three modern proprietary programs, JellyFish,[56] Snowie[57] and eXtreme Gammon,[58] as well as the shareware BGBlitz[59] and the free software GNU Backgammon.[60] These programs not only play the game, but offer tools for analyzing games and detailed comparisons of individual moves. The strength of these programs lies in their neural networks' weights tables, which are the result of months of training. Without them, these programs play no better than a human novice. For the bearoff phase, backgammon software usually relies on a database containing precomputed equities for all possible bearoff positions.

Computer-versus-computer competitions are also held at Computer Olympiad events.

History

Mesopotamia and The Middle East

The history of backgammon can be traced back nearly 5,000 years to its origins in Mesopotamia (modern-day Iraq),[2][3][4][5] the world's oldest set of dice relatable to the game having been discovered in the region. The Royal Game of Ur from 2600 BCE may also be an ancestor or intermediate of modern-day table games like backgammon. It used tetrahedral dice. Various other board games spanning from the 10th to 7th centuries BCE have been found throughout modern day Iraq, Syria, Egypt and western Iran.[61] In the modern Middle East, backgammon is a common feature of coffeehouses. Today the game in various forms continues to be commonly played in Iraq, Lebanon, Egypt, Syria, Jordan throughout the Arab world.

In the modern Arab Levant and Iraq, the game is commonly called tawle, which means table. This may represent a shared name origin with the Roman or Byzantine variant of the game. It is also commonly referred to by shesh besh (shesh meaining six in Hebrew, Aramaic and Northwest Semitic, and besh meaning five in Turkish), amongst Arabs as well as by some Kurdish, Persian and Turkish speakers. Shesh Besh is commonly used to refer to when a player scores a 5 and 6 at the same time on dice.[62]

Persia

An older game resembling backgammon may have also been played in the easternmost part of the prehistoric Iranian plateau, far from Mesopotamia.[63] At the 4,400 year old arecheological site of Shahr-e Sukhteh, The Burnt City, an ebony board was found along with artifacts including two dice and 60 checkers, with the playing fields represented by the coils of a serpent. The rules of this game, like others found in Egypt, have yet to be deciphered. It is however made from ebony, a material more likely to be found in the Indian subcontinent which indicates such board games may be more widespread than once thought.[61][64]

In the 11th century Shahnameh, the Persian poet Ferdowsi credits Burzoe with the invention of the tables game nard in the 6th century. He describes an encounter between Burzoe and a Raja visiting from India. The Raja introduces the game of chess, and Burzoe demonstrates nard, played with dice made from ivory and teak.[2][3] Today, Nard is the name for the Persian version of backgammon, which has different initial positions and objectives.[65] H. J. R. Murray details many versions of backgammon; modern Nard is noted there as being the same as backgammon and maybe dating back to 300–500 AD in the Babylonian Talmud,[3] although others believe the Talmud references the Greek race game Kubeia.

Iranologist Touraj Daryaee, Chair of Persian Studies at U.C. Irvine, on the first written mention of earlier variants of backgammon—writes:

The game of backgammon is first mentioned in Bhartrhari’s Vairagyasataka (p. 39), composed around the late 6th or early 7th century AD. The use of dice for the game is another indication of its Indic origin since dice and gambling were a favorite pastime in ancient India. The rules of the game, however, first appeared in the Middle Persian text Wızarisnı Catrang ud Nihisnı New Ardaxsır (Explanation of Chess and Invention of Backgammon), composed in the 6th century during the rule of the Sasanian king Khosrow I (530–571). The text assigns its invention to the Persian sage Wuzurgmihr (Persian) Buzarjumihr/Bozorgmehr, who was the minister of King Khosrow I. According to the historical legend, the Indian king Dewisarm sends his minister Taxritos to Persia with the game of chess, and a letter challenging Sasanian King Khosrow I to solve the riddle or rationale for the game. Khosrow asks for three days to decipher the game, but initially, no-one in the court is able to make any progress. On the third day, Khosrow's minister, Wuzurgmihr, successfully rises and explains the logic of the game. As a reciprocal challenge, Wuzurgmihr constructs the game of backgammon and delivers it to the Indian king who is unable to decipher the game.[66]

Armenia

Backgammon or nardi (Armenian: նարդի) is very popular among Armenians. The word is derived from Persian word nard (Persian: نرد). There are two games of nardi commonly played:

Short nardi: Set-up and rules are the same as backgammon.[67]

Long nardi: A game that starts with all fifteen checkers placed in one line on the 24-point and on the 11-point. The two players move their checkers in opposing directions, from the 24-point towards the 1-point, or home board. In long nardi, one checker by itself can block a point. There is no hitting in long nardi. The objective of the game is bearing all checkers off the board, and there is no doubling cube.

Roman and Byzantine Empire

Tάβλι (tavli) meaning 'table' or 'board' in Byzantine Greek, is the oldest game with rules known to be nearly identical to backgammon. It is described in an epigram of Byzantine Emperor Zeno (AD 476–491).[68] The board was the same, with 24 points, 12 on each side. Like today, each player had 15 checkers and used cubical dice with sides numbered one to six.[68] The object of the game, to be the first to bear off all of one's checkers, was also the same.[68][69] Hitting a blot, reentering a piece from the bar, and bearing off all followed the modern rules. The only differences from modern backgammon were the use of an extra die (three rather than two) and the starting of all pieces off the board (with them entering in the same way that pieces on the bar enter in modern backgammon).[70] The name τάβλη is still used for backgammon in Greece, where it is frequently played in town plateias and cafes.[71] The epigram of Zeno describes a particularly bad dice roll the emperor had for his given position. Zeno, who was white, had a stack of seven checkers, three stacks of two checkers and two "blots", checkers that stand alone on a point and are therefore in danger of being put outside the board by an incoming opponent checker. Zeno threw the three dice with which the game was played and obtained 2, 5 and 6. As in backgammon, Zeno could not move to a space occupied by two opponent (black) pieces. The white and black checkers were so distributed on the points that the only way to use all of the three results, as required by the game rules, was to break the three stacks of two checkers into blots, exposing them and ruining the game for Zeno.[68][70]

The τάβλη of Zeno's time is believed to be a direct descendant of the earlier Roman Ludus duodecim scriptorum ('Game of twelve lines') with the board's middle row of points removed, and only the two outer rows remaining.[69] Ludus duodecim scriptorum used a board with three rows of 12 points each, with the 15 checkers being moved in opposing directions by the two players across three rows according to the roll of the three cubical dice.[68][69] Little specific text about the gameplay of Ludus duodecim scriptorum has survived;[72] it may have been related to the older Ancient Greek dice game Kubeia. The earliest known mention of the game is in Ovid's Ars Amatoria ('The Art of Love'), written between 1 BC and 8 AD. In Roman times, this game was also known as alea, and a likely apocryphal Latin story linked this name, and the game, to a Trojan soldier named Alea.[73][74]

Egypt

Race board games involving dice have existed for millennia in the Near East and eastern Mediterranean, including the game senet of Ancient Egypt. Senet was excavated, along with illustrations, from Egyptian royal tombs dating to 3500 BC.[75] Though using a board that is quite different from backgammon, it may be a predecessor.

Turkey (Ottoman Empire)

Backgammon, which is known as "tavla", from Byzantine Greek τάβλη,[68] is a very popular game in Turkey, and it is customary to call the dice rolls their Persian number names, with local spellings: yek (1), dü (2), se (3), cehar (4), penç (5), and şeş (6).[76]

The usual Tavla rules are same as in the neighboring Arab countries and Greece, as established over a millennium ago,[68] but there are also many quite different variants. The usual tavla is also known as erkek tavlası, meaning boys' or men's tavla. The other variant, kız tavlası, meaning girls' tavla, is a game that depends only on the dice and involves no strategy. Another variant, asker tavlası, meaning soldiers' tavla, has the pieces thrown on the board randomly. Players try to flip their pieces over the opponents' pieces to beat them.

Greece

Backgammon is popular among Greeks. It is a game in which Greeks usually tease their opponent and create a lively atmosphere[77]. The game is called "Tavli", derived in Byzantine times from the Latin word tabula.[71] A game, almost identical to backgammon, called Tavli (Byzantine Greek: τάβλη) is described in an epigram of the Byzantine Emperor Zeno (AD 476–481).[68] There are four games of Tavli commonly played:

Portes: Set-up and rules the same as backgammon, except that backgammons count as gammons (2 points) and there is no doubling cube.

Plakoto: A game where one checker can trap another checker on the same point.

Fevga: A game where one checker by itself can block a point.

Asodio: Also known as Acey-deucey, where all checkers are off the board, and players enter by rolling either doubles or acey-deucey.

These games are played one after another, in matches of three, five, or seven points.[78] Before starting a match, each player rolls 1 die, and the player with the highest roll picks up both dice and re-rolls (i.e. it is possible to roll doubles for the opening move). Players use the same pair of dice in turns. After the first game, the winner of the previous game starts first. Each game counts as 1 point, if the opponent has borne off at least 1 stone, otherwise 2 points (gammon/backgammon). There is no doubling cube.

East Asia

Backgammon was popular in China for a time and was known as "shuanglu" (雙陸/双陆, shuānglù), with the book Pǔ Shuāng (譜雙) written during the Southern Song period (1127–1279) recording over ten variants. Over time it was replaced by other games such as xiangqi (Chinese chess).[79]

In Japan, ban-sugoroku is thought to have been brought from China in the 6th century, and is mentioned in Genji monogatari. As a gambling game, it was made illegal several times.[80] In the early Edo era, a new and fast gambling game called Chō-han appeared and sugoroku quickly dwindled. By the 13th century, the board game Go, originally played only by the aristocracy, had become popular among the general public.[81]

In Korea, it is called Ssang-ryuk or Jeopo.

Western Europe

The jeux de tables ('Games of Tables'), predecessors of modern backgammon, first appeared in France during the 11th century and became a favorite pastime of gamblers. In 1254, Louis IX issued a decree prohibiting his court officials and subjects from playing.[3][82] Tables games were played in Germany in the 12th century, and had reached Iceland by the 13th century. In Spain, the Alfonso X manuscript Libro de los juegos, completed in 1283, describes rules for a number of dice and table games in addition to its extensive discussion of chess.[83] By the 17th century, table games had spread to Sweden. A wooden board and checkers were recovered from the wreck of the Vasa among the belongings of the ship's officers. Backgammon appears widely in paintings of this period, mainly those of Dutch and German painters, such as Van Ostade, Jan Steen, Hieronymus Bosch, and Bruegel. Some surviving artworks are Cardsharps by Caravaggio (the backgammon board is in the lower left) and The Triumph of Death by Pieter Bruegel the Elder (the backgammon board is in the lower right). Others include Hell (Bosch) and Interior of an Inn by Jan Steen.

Great Britain

In the 16th century, Elizabethan laws and church regulations prohibited playing tables, but by the 18th century, backgammon was popular among the English clergy.[3] Edmond Hoyle published A Short Treatise on the Game of Back-Gammon in 1753; this described rules and strategy for the game and was bound together with a similar text on whist.[84]

In English, the word "backgammon" is most likely derived from "back" and Middle English: gamen, meaning "game" or "play". The earliest use documented by the Oxford English Dictionary was in 1650.[85]

United States

The most recent major development in backgammon was the addition of the doubling cube. It was first introduced in the 1920s in New York City among members of gaming clubs in the Lower East Side.[86] The cube required players not only to select the best move in a given position, but also to estimate the probability of winning from that position, transforming backgammon into the expected value-driven game played in the 20th and 21st centuries.[86]

The popularity of backgammon surged in the mid-1960s, in part due to the charisma of Prince Alexis Obolensky who became known as "The Father of Modern Backgammon".[87] "Obe", as he was called by friends, co-founded the International Backgammon Association,[88] which published a set of official rules. He also established the World Backgammon Club of Manhattan, devised a backgammon tournament system in 1963, then organized the first major international backgammon tournament in March 1964, which attracted royalty, celebrities and the press. The game became a huge fad and was played on college campuses, in discothèques and at country clubs;[87] stockbrokers and bankers began playing at conservative men's clubs.[89] People young and old all across the country dusted off their boards and checkers. Cigarette, liquor and car companies began to sponsor tournaments, and Hugh Hefner held backgammon parties at the Playboy Mansion.[90] Backgammon clubs were formed and tournaments were held, resulting in a World Championship promoted in Las Vegas in 1967.[44]

Most recently, the United States Backgammon Federation (USBGF) was organized in 2009 to repopularize the game in the United States. Board and committee members include many of the top players, tournament directors and writers in the worldwide backgammon community. The USBGF has recently created a Standards of Ethical Practice to address issues on which tournament rules fail to touch.

See also

- Backgammon notation

- Category:Backgammon players

- Tables (board game)

- Table games

- TD-Gammon

References

- http://www.payvand.com/news/04/dec/1029.html

- Wilkinson, Charles K (May 1943). "Chessmen and Chess" (PDF). The Metropolitan Museum of Art Bulletin. New Series 1 (9): 271–279. doi:10.2307/3257111. JSTOR 3257111. S2CID 51826948.

- Murray, H. J. R. (1952). "6: Race-Games". A History of Board-Games Other than Chess. Hacker Art Books. ISBN 978-0-87817-211-5.

- Chris Bray (14 February 2011). Backgammon For Dummies. John Wiley & Sons. pp. 31–. ISBN 978-1-119-99674-3.

- Chris Bray (2012). Backgammon to Win. Lulu Com. pp. 6–. ISBN 978-1-291-01965-0.

- Murphy, Daniel (30 April 2001). "Re: International Tourny Formats Rules - Who Can Help?". Backgammon Galore!.

Rules of play describe a particular variation of backgammon and on this there is no disagreement among international tournaments. In fact, tournament rules sets do not usually specify these rules but might instead refer, as in the US Rules, to the 'commonly accepted rules of backgammon.' It is understood that this means backgammon as played at international tournaments, not another variant in its own right such as plakoto, portes, fevka or portos.

- Chris Bray (14 February 2011). Backgammon For Dummies. p. 23. ISBN 9781119996743.

- Nicolae Sfetcu (9 November 2016). Gaming Guide - Gambling in Europe. p. 39.

- Robertie, Bill (2002). Backgammon for Winners (Third ed.). Cardoza. ISBN 978-1-58042-043-3.

- Morehead, Albert H.; Mott-Smith, Geoffrey, eds. (2001). Hoyle's Rules of Games (Third Revised and Updated ed.). Signet. pp. 321–330. ISBN 978-0-451-20484-4.

- "Rules of Backgammon". Backgammon Galore!.

To start the game, each player throws a single die. This determines both the player to go first and the numbers to be played.

- Robertie, Bill. "Backgammon Beavers". GammonVillage. Retrieved 2007-10-17.

- Robertie, Bill (2006). Backgammon for Serious Players (Second ed.). Cardoza. pp. 19–22. ISBN 978-0-940685-68-0.

- "Backgammon Glossary/Holland Rule". Backgammon Galore!. Archived from the original on 2016-03-12. Retrieved 2009-02-26.

- The Backgammon Book, Chapter 11, O. Jacoby & J. R. Crawford, 1970, Macmillan & Co

- Tesauro, G. (2002). "Programming backgammon using self-teaching neural nets" (PDF). Artificial Intelligence. 134 (1): 181–199. doi:10.1016/S0004-3702(01)00110-2. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2007-09-27. Retrieved 2007-08-08.

- Strato, Michael. "Backgammon Variants". Gammonlife. Archived from the original on 13 September 2007. Retrieved 2007-08-08.

- Thompson, Mark. "Nackgammon". mindfun. Archived from the original on 2008-10-09. Retrieved 2009-02-04.

- Woolsey, Kit (September 2001). "Nackgammon". Gammonline. Archived from the original on 2007-09-28. Retrieved 2007-08-08.

- "Draughts and Backgammon", 1895, Berkeley

- "Russian Backgammon". Backgammon Galore!. Archived from the original on 13 March 2009. Retrieved 2009-02-26.

- "... The three games together are called 'Tavli' and are usually played one after the other in matches of three, five, or seven points...", Backgammon Galore! page

- "Misere (Backgammon to Lose)". Backgammon Galore!. Retrieved 2020-08-14.

- "Traditional Backgammon Rules". VIP Backgammon.

- "Old English Backgammon". Backgammon Galore!.

- "Backgammon FAQ: Basic Rules". Backgammon Galore!.

- "Backgammon Rules – And How To Play". US Backgammon Federation.

- Magriel, Paul (1976). Backgammon. Quadrangle/The New York Times Book Co. ISBN 978-0-8129-0615-8.

- "Backgammon Glossary/Back Game". Backgammon Galore!.

- Keeler, Emmet; Spencer, Joel (1975). "Optimal Doubling in Backgammon". Operations Research. 23 (6): 1063–1071. doi:10.1287/opre.23.6.1063.

- Bray, Chris (2008). Backgammon for Dummies. John Wiley & Sons. p. 13 and 224. ISBN 978-0-470-69456-5.

- Harrington Green, Jonathan (1845). An exposure of the arts and miseries of gambling. Redding. p. 203.

- Rosenthal, Franz. Humor in Early Islam (2011), BRILL p.98

- https://www.islamweb.net/en/fatwa/91109/

- Kareem Shaheen (2016-01-26). "Chess forbidden in Islam, rules Saudi mufti, but issue not black and white". The Guardian. Retrieved 2019-10-18.

- "The Trial (and Tribulations) of Oregon Promoter Ted Barr". Backgammon Times. 2 (2). 1982.

- "Tribes of Sydney—Sydney Backgammon Club". The Daily Telegraph (Australia). June 24, 2006. p. 95.

- Bray, Chris (June 29, 2002). "Backgammon". The Independent (London). p. 50.

- Bray, Chris (November 25, 2000). "Backgammon". The Independent (London). p. 19.

- Laverty, Roy (May 16, 2003). "Backgammon warriors—columnist, club member square off as board game's popularity grows". Alameda Times-Star (Section: Bay Area Living).

- Magriel, Paul (June 1, 1980). "Backgammon: Before Planning Big Attack, Be Sure to Cover Your Rear". The New York Times, Late City Final Edition. pp. 50, section 1, part 2.

- Maxa, Rudy (September 6, 1981). "Where the Rich And the Royal Play Their Games—Monte Carlo's Seven-Day Backgammon Soiree With Countesses, Princes and Other Sharpies". The Washington Post. p. H1.

- "GammonPoints". www.gammonpoints.com. Retrieved 2018-03-26.

- Play65, The History of the World Backgammon Championships

- Michael Crane (July 25, 2000). "Backgammon News—World Championships 2000". Mind Sports Worldwide. Archived from the original on 7 September 2006. Retrieved 2006-09-14.

- "PartyGammon.com to Stage First Ever US$1 Million Backgammon Tournament". PR Newswire. Lexis-Nexis. July 10, 2006.

- "World Backgammon Association". www.world-backgammon-association.com.

- "Home". www.ebgt.info.

- Wachtel, Robert. "Backgammon Proposition". backgammon.org. Archived from the original on 2009-10-10.

- "Nintendo Shares A Handy Infographic Featuring All 51 Worldwide Classic Clubhouse Games". Nintendo Life. Retrieved 2020-07-21.

- Schneider, Andreas; et al. "Brief history of FIBS". FIBS, the First Internet Backgammon Server. Archived from the original on 2006-08-13. Retrieved 2006-08-05.

- Schneider, Andreas. " "Backgammon server available NOW". Retrieved 2012-02-11.

- Keith, Tom. "Backgammon Play Sites". Backgammon Galore!. Retrieved 6 March 2017.

- Berliner, Hans (January 1980). "Backgammon program beats world champ". ACM SIGART Bulletin (69): 6–9. doi:10.1145/1056433.1056434. S2CID 36222242.

- Tesauro, Gerald (March 1995). "Temporal difference learning and TD-Gammon". Communications of the ACM. 38 (3): 58–68. doi:10.1145/203330.203343. S2CID 8763243.

- "Backgammon software - Backgammon Online Guide". www.backgammon.help. Archived from the original on 2015-08-16. Retrieved 2015-08-10.

- "BackgammonSnowie - World class poker coaching software". www.bgsnowie.com.

- "eXtreme Gammon". www.extremegammon.com.

- "BGBlitz". BGBlitz. Archived from the original on 25 February 2009. Retrieved 2009-02-26.

- GNU Backgammon.

- Schädler, Ulrich; Dunn-Vaturi, Anne-Elizabeth. "Board Games in pre-Islamic Persia". Encyclopædia Iranica. Retrieved 2018-04-11.

- Marijean Boueri; Jill Boutros; Joanne Sayad (April 2006). Lebanon A to Z: A Middle Eastern Mosaic. PublishingWorks. pp. 59–. ISBN 978-0-9744803-4-3.

- "World's Oldest Backgammon Discovered In Burnt City". Payvand News. December 4, 2004. Retrieved 2010-05-07.

- https://www.kavehfarrokh.com/news/burnt-city-worlds-oldest-backgammon-game/

- "Backgammon, or Takheth Nard".

- Daryaee, Touraj (2006) in "Backgammon" in Medieval Islamic Civilization: An Encyclopedia ed. Meri, Josef W. & Bacharach, Jere L, pp. 88-89. Taylor & Francis.

- https://www.vnews.am/kartch-nardi-xaghalu-kanonnereh-ev-orenkhnereh/

- Austin, Roland G (1934). "Zeno's Game of τάβλη". The Journal of Hellenic Studies. 54 (2): 202–205. doi:10.2307/626864. JSTOR 626864.

- Austin, Roland G. (February 1935). "Roman Board Games. II". Greece & Rome. 4 (11): 76–82. doi:10.1017/s0017383500003119.

- Robert Charles Bell, Board and table games from many civilizations, Courier Dover Publications, 1979, ISBN 0-486-23855-5, pp. 33–35.

- Koukoules, Phaidon (1948). Vyzantinon Vios kai Politismos. 1. Collection de l'institut français d'Athènes. pp. 200–204.

- Austin, Roland G. (October 1934). "Roman Board Games. I". Greece & Rome. 4 (10): 24–34. doi:10.1017/s0017383500002941.

- Finkel, Irving L. "Ancient board games in perspective." British Museum Colloquium. 2007. p. 224

- Jacoby, Oswald, and John R. Crawford. The backgammon book. Viking Pr, 1976.

- Hayes, William C. (March 1946). "Egyptian Tomb Reliefs of the Old Kingdom". The Metropolitan Museum of Art Bulletin. New Series 4 (7): 170–178. doi:10.2307/3257177. JSTOR 3257177.

- Ergil, Leyla Yvonne. "Top Tavla tips for expats to play like a Turk". Daily Sabah. dailysabah.com. Retrieved 1 February 2017.

- "Playing Tavli (Backgammon) in Greece with Omilo". omilo.com. Retrieved 22 January 2021.

- "Tavli (Greek Backgammon)". Backgammon Galore!. 2003. Archived from the original on 13 August 2006. Retrieved 2006-08-05.

- "CCTV.com-[博弈篇]舶来棋戏——双陆". news.cctv.com.

- Origin of Sugoroku in Japan, sugoroku.net

- "History of Go in Japan: part 3". Nihon Kiin. Archived from the original on 14 November 2007. Retrieved 2007-11-02.

- Lillich, Meredith Parsons (March 1983). "The Tric-Trac Window of Le Mans". The Art Bulletin. 65 (1): 23–33. doi:10.2307/3050296. JSTOR 3050296.

- Wollesen, Jens T. (1990). "Sub specie ludi...: Text and Images in Alfonso El Sabio's Libro de Acedrex, Dados e Tablas". Zeitschrift für Kunstgeschichte. 53 (3): 277–308. doi:10.2307/1482540. JSTOR 1482540.

- Allee, Sheila. "A Foregone Conclusion: Fore-Edge Books Are Unique Additions to Ransom Collection". The University of Texas at Austin. Archived from the original on 2006-06-21. Retrieved 2006-08-08.

- "backgammon". The Oxford English Dictionary (Second ed.). 1989. Retrieved 2006-08-05.

- Robertie, Bill (2002). 501 Essential Backgammon Problems (Second Printing ed.). Cardoza. p. 22. ISBN 978-1-58042-019-8.

- "The Inventor of Doubling in Backgammon". www.gammonlife.com.

- "The Father Of Modern Backgammon - GammonVillage Magazine". www.gammonvillage.com.

- "Urge to Play Backgammon Sweeping Men's Clubs". The New York Times. January 13, 1966. Retrieved 2010-09-10.

A disk and dice game that has been played in Middle Eastern streets for thousands of years, in English homes for hundreds of years, and on Bronx stoops for dozens of years has suddenly gripped the bankers and brokers of old-line men's clubs all over town.

- "World Backgammon Championships History - Backgammon Masters - Backgammon Articles' Categories - Play65™". www.play65.com.

Further reading

- Gardner, Iain (2020). "Backgammon and cosmology at the Sasanian court". Bulletin of the School of Oriental and African Studies. 83 (2): 249–257. doi:10.1017/S0041977X20002177.

- van Gelder, Geert Jan (2021). "Backgammon". In Fleet, Kate; Krämer, Gudrun; Matringe, Denis; Nawas, John; Rowson, Everett (eds.). Encyclopaedia of Islam, THREE. Brill Online. ISSN 1873-9830.

External links

The dictionary definition of Appendix:Glossary of backgammon terms at Wiktionary

The dictionary definition of Appendix:Glossary of backgammon terms at Wiktionary Backgammon at Wikibooks

Backgammon at Wikibooks Media related to Backgammon at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Backgammon at Wikimedia Commons- . Encyclopædia Britannica (11th ed.). 1911.