Vasa (ship)

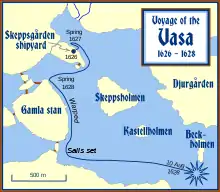

Vasa or Wasa[lower-alpha 1] (Swedish pronunciation: [²vɑːsa] (![]() listen)) is a Swedish warship built between 1626 and 1628. The ship foundered after sailing about 1,300 m (1,400 yd) into her maiden voyage on 10 August 1628. She fell into obscurity after most of her valuable bronze cannon were salvaged in the 17th century, until she was located again in the late 1950s in a busy shipping area in Stockholm harbor. The ship was salvaged with a largely intact hull in 1961. She was housed in a temporary museum called Wasavarvet ("The Vasa Shipyard") until 1988 and then moved permanently to the Vasa Museum in the Royal National City Park[2] in Stockholm. The ship is one of Sweden's most popular tourist attractions and has been seen by over 35 million visitors since 1961.[3] Since her recovery, Vasa has become a widely recognised symbol of the "Swedish Empire".

listen)) is a Swedish warship built between 1626 and 1628. The ship foundered after sailing about 1,300 m (1,400 yd) into her maiden voyage on 10 August 1628. She fell into obscurity after most of her valuable bronze cannon were salvaged in the 17th century, until she was located again in the late 1950s in a busy shipping area in Stockholm harbor. The ship was salvaged with a largely intact hull in 1961. She was housed in a temporary museum called Wasavarvet ("The Vasa Shipyard") until 1988 and then moved permanently to the Vasa Museum in the Royal National City Park[2] in Stockholm. The ship is one of Sweden's most popular tourist attractions and has been seen by over 35 million visitors since 1961.[3] Since her recovery, Vasa has become a widely recognised symbol of the "Swedish Empire".

Vasa's port bow | |

| History | |

|---|---|

| Laid down: | 1626 |

| Launched: | March 1627 |

| Fate: | Sank in 1628, salvaged in 1961, currently a museum ship |

| General characteristics | |

| Tonnage: | 1210 tonnes displacement |

| Length: |

|

| Beam: | 11.7 m (38 ft) |

| Height: | 52.5 m (172 ft) |

| Draft: | 4.8 m (16 ft) |

| Propulsion: | Sails, 1,275 square m (13,720 sq ft) |

| Crew: | 145 sailors, 300 soldiers |

| Armament: |

|

| Notes: | Source for dimensions & tonnage[1] |

The ship was built on the orders of the King of Sweden Gustavus Adolphus as part of the military expansion he initiated in a war with Poland-Lithuania (1621–1629). She was constructed at the navy yard in Stockholm under a contract with private entrepreneurs in 1626–1627 and armed primarily with bronze cannons cast in Stockholm specifically for the ship. Richly decorated as a symbol of the king's ambitions for Sweden and himself, upon completion she was one of the most powerfully armed vessels in the world. However, Vasa was dangerously unstable, with too much weight in the upper structure of the hull. Despite this lack of stability, she was ordered to sea and foundered only a few minutes after encountering a wind stronger than a breeze.

The order to sail was the result of a combination of factors. The king, who was leading the army in Poland at the time of her maiden voyage, was impatient to see her take up her station as flagship of the reserve squadron at Älvsnabben in the Stockholm Archipelago. At the same time the king's subordinates lacked the political courage to openly discuss the ship's problems or to have the maiden voyage postponed. An inquiry was organised by the Swedish Privy Council to find those responsible for the disaster, but in the end no one was punished.

During the 1961 recovery, thousands of artifacts and the remains of at least 15 people were found in and around Vasa's hull by marine archaeologists. Among the many items found were clothing, weapons, cannons, tools, coins, cutlery, food, drink and six of the ten sails. The artifacts and the ship herself have provided scholars with invaluable insights into details of naval warfare, shipbuilding techniques and everyday life in early 17th-century Sweden. Today Vasa is the world's best preserved 17th century ship and the most visited museum in Scandinavia.[4] The wreck of Vasa continually undergoes monitoring and further research on how to preserve her.[5]

.jpg.webp)

Historical background

During the 17th century, Sweden went from being a sparsely populated, poor, and peripheral northern European kingdom of little influence to one of the major powers in continental politics. Between 1611 and 1718 it was the dominant power in the Baltic, eventually gaining territory that encompassed the Baltic on all sides. This rise to prominence in international affairs and increase in military prowess, called stormaktstiden ("age of greatness" or "great power period"), was made possible by a succession of able monarchs and the establishment of a powerful centralised government, supporting a highly efficient military organization. Swedish historians have described this as one of the more extreme examples of an early modern state using almost all of its available resources to wage war; the small northern kingdom transformed itself into a fiscal-military state and one of the most militarised states in history.[6]

Gustavus Adolphus (1594–1632) has been considered one of the most successful Swedish kings in terms of success in warfare. When Vasa was built, he had been in power for more than a decade. Sweden was embroiled in a war with Poland-Lithuania, and looked apprehensively at the development of the Thirty Years' War in present-day Germany. The war had been raging since 1618 and from a Protestant perspective it was not successful. The king's plans for a Polish campaign and for securing Sweden's interests required a strong naval presence in the Baltic.[7]

The navy suffered several severe setbacks during the 1620s. In 1625, a squadron cruising in the Bay of Riga was caught in a storm and ten ships ran aground and were wrecked. In the Battle of Oliwa in 1627, a Swedish squadron was outmaneuvered and defeated by a Polish force and two large ships were lost. Tigern ("The Tiger"), which was the Swedish admiral's flagship, was captured by the Poles, and Solen ("The Sun") was blown up by her own crew when it was boarded and nearly captured. In 1628, three more large ships were lost in less than a month; Admiral Klas Fleming's flagship Kristina was wrecked in a storm in the Gulf of Danzig, Riksnyckeln ("Key of the Realm") ran aground at Viksten in the southern archipelago of Stockholm and Vasa foundered on her maiden voyage. Gustavus Adolphus was engaged in naval warfare on several fronts, which further exacerbated the difficulties of the navy. In addition to battling the Polish navy, the Swedes were indirectly threatened by Imperial forces that had invaded Jutland. The Swedish king had little sympathy for the Danish king, Christian IV, and Denmark and Sweden had been bitter enemies for well over a century. However, Sweden feared a Catholic conquest of Copenhagen and Zealand. This would have granted the Catholic powers control over the strategic passages between the Baltic Sea and the North Sea, which would be disastrous for Swedish interests.[7][8]

Until the early 17th century, the Swedish navy was composed primarily of small to medium-sized ships with a single gundeck, normally armed with 12-pounder and smaller cannons; these ships were cheaper than larger ships and were well-suited for escort and patrol. They also suited the prevailing tactical thinking within the navy, which emphasised boarding as the decisive moment in a naval battle rather than gunnery. The king, who was a keen artillerist, saw the potential of ships as gun platforms, and large, heavily armed ships made a more dramatic statement in the political theater of naval power. Beginning with Vasa, he ordered a series of ships with two full gundecks, outfitted with much heavier guns.[9] Five such ships were built after Vasa (Äpplet, Kronan, Scepter and Göta Ark) before the Privy Council cancelled the orders for the others after the king's death in 1632. These ships, especially Kronan and Scepter, were much more successful and served as flagships in the Swedish navy until the 1660s. The second of the so-called regalskepp (usually translated as "royal ships"),[10] Äpplet ("The Apple"; the Swedish term for the globus cruciger), was built simultaneously with Vasa. The only significant difference between the design of Vasa and her sister ship was an increase in width of about a metre (3.1 ft).[11]

Construction

Just before Vasa was ordered, Dutch-born Henrik Hybertsson ("Master Henrik") was shipwright at the Stockholm shipyard. On 16 January 1625, Master Henrik and business partner Arendt de Groote signed a contract to build four ships, two with a keel of around 135 feet (41 m) and two smaller ones of 108 feet (33 m).[12]

Master Henrik and Arendt de Groote began buying the raw materials needed for the first ships in 1625, purchasing timber from individual estates in Sweden as well as buying rough-sawn planking in Riga, Königsberg (modern Kaliningrad), and Amsterdam. As they prepared to begin the first of the new ships in the autumn of 1625, Henrik corresponded with the king through Vice Admiral Klas Fleming about which ship to build first. The loss of ten ships in the Bay of Riga led the king to propose building two ships of a new, medium size as a quick compromise, and he sent a specification for this, a ship which would be 120 feet (35.6 m) long on the keel. Henrik declined, since he had already cut the timber for a large and a small ship. He laid the keel for a larger ship in late February or early March 1626.[13] Master Henrik never saw Vasa completed; he fell ill in late 1625, and by the summer of 1626 he had handed over supervision of the work in the yard to another Dutch shipwright, Henrik "Hein" Jacobsson. He died in the spring of 1627, probably about the same time as the ship was launched.[14]

After launching, work continued on finishing the upper deck, the sterncastle, the beakhead and the rigging. Sweden had still not developed a sizeable sailcloth industry, and material had to be ordered from abroad. In the contract for the maintenance of rigging, French sailcloth was specified, but the cloth for the sails of Vasa most likely came from Holland.[15] The sails were made mostly of hemp and partly of flax. The rigging was made entirely of hemp imported from Latvia through Riga. The king visited the shipyard in January 1628 and made what was probably his only visit aboard the ship.[16]

In the summer of 1628, the captain responsible for supervising construction of the ship, Söfring Hansson, arranged for the ship's stability to be demonstrated for Vice Admiral Fleming, who had recently arrived in Stockholm from Prussia. Thirty men ran back and forth across the upper deck to start the ship rolling, but the admiral stopped the test after they had made only three trips, as he feared the ship would capsize. According to testimony by the ship's master, Göran Mattson, Fleming remarked that he wished the king were at home. Gustavus Adolphus had been sending a steady stream of letters insisting that the ship put to sea as soon as possible.[17]

There has been much speculation about whether Vasa was lengthened during construction and whether an additional gun deck was added late during the build. Little evidence suggests that Vasa was substantially modified after the keel was laid. Ships contemporary to Vasa that were elongated were cut in half and new timbers spliced between the existing sections, making the addition readily identifiable, but no such addition can be identified in the hull, nor is there any evidence for any late additions of a second gundeck. The king ordered 72 24-pound guns for the ship on 5 August 1626, and this was too many to fit on a single gun deck. Since the king's order was issued less than five months after construction started, it would have come early enough for the second deck to be included in the design. The French Galion du Guise, the ship used as a model for Vasa, according to Arendt de Groote, also had two gun decks.[18] Laser measurements of Vasa's structure conducted in 2007–2011 confirmed that no major changes were implemented during construction, but that the centre of gravity was too high.[19]

Vasa was an early example of a warship with two full gun decks, and was built when the theoretical principles of shipbuilding were still poorly understood. There is no evidence that Henrik Hybertsson had ever built a ship like it before, and two gundecks is a much more complicated compromise between seaworthiness and firepower than a single gundeck. Safety margins at the time were also far below anything that would be acceptable today. Combined with the fact that 17th-century warships were built with intentionally high superstructures (to be used as firing platforms), this made Vasa a risky undertaking.[20]

Armament

Vasa was built during a time of transition in naval tactics, from an era when boarding was still one of the primary ways of fighting enemy ships to an era of the strictly organised ship-of-the-line and a focus on victory through superior gunnery. Vasa was armed with powerful guns and built with a high stern, which would act as a firing platform in boarding actions for some of the 300 soldiers it was supposed to carry, but the high-sided hull and narrow upper deck were not optimised for boarding. It was neither the largest ship ever built, nor the one carrying the greatest number of guns. What made her arguably the most powerful warship of the time was the combined weight of shot that could be fired from the cannon of one side: 588 pounds (267 kg), excluding stormstycken, guns used for firing anti-personnel ammunition instead of solid shot. This was the largest concentration of artillery in a single warship in the Baltic at the time, perhaps in all of northern Europe, and it was not until the 1630s that a ship with more firepower was built. This large amount of naval artillery was placed on a ship that was quite small relative to the armament carried. By comparison, USS Constitution, a frigate built by the United States 169 years after Vasa, had roughly the same firepower, but was over 700 tonnes heavier.[21]

The Constitution, however, belonged to a later era of naval warfare that employed the line of battle-tactic, where ships fought in single file (or line ahead) while the group as a whole attempted to present the batteries of one side toward the enemy. The guns would be aimed in the same direction and fire could be concentrated on a single target. In the 17th century, tactics involving organised formations of large fleets had still not been developed. Rather, ships would fight individually or in small improvised groups, and focused on boarding. Vasa, though possessing a formidable battery, was built with these tactics in mind, and therefore lacked a unified broadside with guns that were all aimed in roughly the same direction. Rather, the guns were intended to be fired independently and were arranged according to the curvature of the hull, meaning that the ship would be bristled with artillery in all directions, covering virtually all angles.[22]

Naval gunnery in the 17th century was still in its infancy. Guns were expensive and had a much longer lifespan than any warship. Guns with a lifetime of over a century were not unheard of, while most warships would be used for only 15 to 20 years. In Sweden and many other European countries, a ship would normally not "own" its guns, but would be issued armament from the armory for every campaign season. Ships were therefore usually fitted with guns of very diverse age and size. What allowed Vasa to carry so much firepower was not merely that an unusually large number of guns were crammed into a relatively small ship, but also that the 46 main 24-pounder guns were of a new and standardised lightweight design, cast in a single series at the state gun foundry in Stockholm, under the direction of the Swiss-born founder Medardus Gessus. Two additional 24-pounders, of a heavier and older design, were mounted in the bows, the so-called bow chasers. Four more heavy guns were intended for the stern, but the cannon foundry could not cast guns as fast as the navy yard could build ships, and Vasa waited nearly a year after construction was finished for its armament. When the ship sailed in August 1628, eight of the planned armament of 72 guns had still not been delivered. All cannons during this time had to be made from individually made moulds that could not be reused, but Vasa's guns had such uniform precision in their manufacturing that their primary dimensions varied by only a few millimetres, and their bores were almost exactly 146 mm (5.7 in). The remaining armament of Vasa consisted of eight 3-pounders, six large caliber stormstycken (similar to what the English called howitzers) for use during boarding actions, and two 1-pound falconets. Also included on board were 894 kilograms (1,970 lb) of gunpowder and over 1,000 shot of various types for the guns.[23]

Ornamentation

As was the custom with warships at the time, parts of Vasa were decorated with sculptures. Residues of paint have been found on many sculptures and on other parts of the ship. The entire ornamentation was once painted in vivid colors. The sides of the beakhead (the protruding structure below the bowsprit), the bulwarks (the protective railing around the weather deck), the roofs of the quarter galleries, and the background of the transom (the flat surface at the stern of the ship) were all painted red, while the sculptures were decorated in bright colors, and the dazzling effect of these was in some places emphasised with gold leaf. Previously, it was believed that the background color had been blue and that all sculptures had been almost entirely gilded, and this is reflected in many paintings of Vasa from the 1970s to the early 1990s, such as the lively and dramatic drawings of Björn Landström or the painting by Francis Smitheman.[24] In the late 1990s, this view was revised and the colors are properly reflected in more recent reproductions of the ship's decoration by maritime painter Tim Thompson and the 1:10 scale model in the museum. Vasa is an example not so much of the heavily gilded sculptures of early Baroque art but rather "the last gasps of the medieval sculpture tradition" with its fondness for gaudy colors, in a style that today would be considered extravagant or even vulgar.[8]

The sculptures are carved out of oak, pine or linden, and many of the larger pieces, like the huge 3-metre (10 ft) long figurehead lion, consist of several parts carved individually and fitted together with bolts. Close to 500 sculptures, most of which are concentrated on the high stern and its galleries and on the beakhead, are found on the ship.[25] The figure of Hercules appears as a pair of pendants, one younger and one older, on each side of the lower stern galleries; the pendants depict opposite aspects of the ancient hero, who was extremely popular during antiquity as well as in 17th-century European art. On the transom are biblical and nationalistic symbols and images. A particularly popular motif is the lion, which can be found as the mascarons originally fitted on the insides of the gunport doors, grasping the royal coat of arms on either side, the figurehead, and even clinging to the top of the rudder. Each side of the beakhead originally had 20 figures (though only 19 have actually been found) that depicted Roman emperors from Tiberius to Septimius Severus. Overall, almost all heroic and positive imagery is directly or indirectly identified with the king and was originally intended to glorify him as a wise and powerful ruler. The only actual portrait of the king, however, is located at the very top of the transom in the stern. Here he is depicted as a young boy with long, flowing hair, being crowned by two griffins representing the king's father, Charles IX.[26]

A team of at least six expert sculptors worked for a minimum of two years on the sculptures, most likely with the assistance of an unknown number of apprentices and assistants. No direct credit for any of the sculptures has been provided, but the distinct style of one of the most senior artists, Mårten Redtmer, is clearly identifiable. Other accomplished artists, like Hans Clausink, Johan Didrichson Tijsen (or Thessen in Swedish) and possibly Marcus Ledens, are known to have been employed for extensive work at the naval yards at the time Vasa was built, but their respective styles are not distinct enough to associate them directly with any specific sculptures.[27]

The artistic quality of the sculptures varies considerably, and about four distinct styles can be identified. The only artist who has been positively associated with various sculptures is Mårten Redtmer, whose style has been described as "powerful, lively and naturalistic".[28] He was responsible for a considerable number of the sculptures. These include some of the most important and prestigious pieces: the figurehead lion, the royal coat of arms, and the sculpture of the king at the top of the transom. Two of the other styles are described as "elegant ... a little stereotyped and manneristic", and of a "heavy, leisurely but nevertheless rich and lively style", respectively. The fourth and last style, deemed clearly inferior to the other three, is described as "stiff and ungainly"[29] and was done by other carvers, perhaps even apprentices, of lesser skill.[30]

Maiden voyage

On 10 August 1628, Captain Söfring Hansson ordered Vasa to depart on her maiden voyage to the naval station at Älvsnabben. The day was calm, and the only wind was a light breeze from the southwest. The ship was warped (hauled by anchor) along the eastern waterfront of the city to the southern side of the harbor, where four sails were set, and the ship made way to the east. The gun ports were open, and the guns were out to fire a salute as the ship left Stockholm.[17]

As Vasa passed under the lee of the bluffs to the south (what is now Södermalm), a gust of wind filled her sails, and she heeled suddenly to port. The sheets were cast off, and the ship slowly righted herself as the gust passed. At Tegelviken, where there is a gap in the bluffs, an even stronger gust again forced the ship onto its port side, this time pushing the open lower gunports under the surface, allowing water to rush in onto the lower gundeck. The water building up on the deck quickly exceeded the ship's minimal ability to right itself, and water continued to pour in until it ran down into the hold; the ship quickly sank to a depth of 32 m (105 ft) only 120 m (390 ft) from shore. Survivors clung to debris or the upper masts, which were still above the surface. Many nearby boats rushed to their aid, but despite these efforts and the short distance to land, 30 people reportedly perished with the ship. Vasa sank in full view of a crowd of hundreds, if not thousands, of mostly ordinary Stockholmers who had come to see the great ship set sail. The crowd included foreign ambassadors, in effect spies of Gustavus Adolphus' allies and enemies, who also witnessed the catastrophe.[31]

Inquest

The Council sent a letter to the king the day after the loss, telling him of the sinking, but it took over two weeks to reach him in Poland. "Imprudence and negligence" must have been the cause, he wrote angrily in his reply, demanding in no uncertain terms that the guilty parties be punished.[32] Captain Söfring Hansson, who survived the disaster, was immediately taken for questioning. Under initial interrogation, he swore that the guns had been properly secured and that the crew was sober. A full inquest before a tribunal of members of the Privy Council and Admiralty took place at the Royal Palace on 5 September 1628. Each of the surviving officers was questioned as was the supervising shipwright and a number of expert witnesses. Also present at the inquest was the Admiral of the Realm, Carl Carlsson Gyllenhielm. The object of the inquest was as much or more to find a scapegoat as to find out why the ship had sunk. Whoever the committee might find guilty for the fiasco would face a severe penalty.[32]

Surviving crew members were questioned one by one about the handling of the ship at the time of the disaster. Was it rigged properly for the wind? Was the crew sober? Was the ballast properly stowed? Were the guns properly secured? However, no-one was prepared to take the blame. Crewmen and contractors formed two camps; each tried to blame the other, and everyone swore he had done his duty without fault and it was during the inquest that the details of the stability demonstration were revealed.[33]

Next, attention was directed to the shipbuilders. "Why did you build the ship so narrow, so badly and without enough bottom that it capsized?" the prosecutor asked the shipwright Jacobsson.[34] Jacobsson stated that he built the ship as directed by Henrik Hybertsson (long since dead and buried), who in turn had followed the specification approved by the king. Jacobsson had in fact widened the ship by 1 foot 5 inches (c. 42 cm) after taking over responsibility for the construction, but construction of the ship was too far advanced to allow further widening.[34]

In the end, no guilty party could be found. The answer Arendt de Groote gave when asked by the court why the ship sank was "Only God knows". Gustavus Adolphus had approved all measurements and armaments, and the ship was built according to the instructions and loaded with the number of guns specified. In the end, no-one was punished or found guilty for negligence, and the blame effectively fell on Henrik Hybertsson.[35]

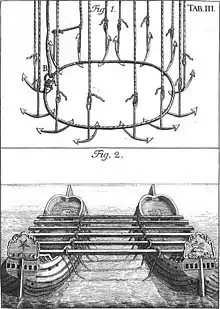

Vasa as a wreck

Less than three days after the disaster, a contract was signed for the ship to be raised. However, those efforts were unsuccessful.[36] The earliest attempts at raising Vasa by English engineer Ian Bulmer,[37] resulted in righting the ship but also got it more securely stuck in the mud and was most likely one of the biggest impediments to the earliest attempts at recovery.[36] Salvaging technology in the early 17th century was much more primitive than today, but the recovery of ships used roughly the same principles as were used to raise Vasa more than 300 years later. Two ships or hulks were placed parallel to either side above the wreck, and ropes attached to several anchors were sent down and hooked to the ship. The two hulks were filled with as much water as was safe, the ropes tightened, and the water pumped out. The sunken ship then rose with the ships on the surface and could be towed to shallower waters. The process was then repeated until the entire ship was successfully raised above water level. Even if the underwater weight of Vasa was not great, the mud in which it had settled made it sit more securely on the bottom and required considerable lifting power to overcome.[38] More than 30 years after the ship's sinking, in 1663–1665, Albreckt von Treileben and Andreas Peckell mounted an effort to recover the valuable guns. With a simple diving bell, the team of Swedish and Finnish divers retrieved more than 50 of them.[39]

Such activity waned when it became clear that the ship could not be raised by the technology of the time. However, Vasa did not fall completely into obscurity after the recovery of the guns. The ship was mentioned in several histories of Sweden and the Swedish Navy, and the location of the wreck appeared on harbor charts of Stockholm in the 19th century. In 1844, the navy officer Anton Ludwig Fahnehjelm turned in a request for salvaging rights to the ship, claiming he had located it. Fahnehjelm was an inventor who designed an early form of light diving suit and had previously been involved in other salvage operations. There were dives made on the wreck in 1895–1896, and a commercial salvage company applied for a permit to raise or salvage the wreck in 1920, but this was turned down. In 1999, a witness also claimed that his father, a petty officer in the Swedish navy, had taken part in diving exercises on Vasa in the years before World War I.[40]

Deterioration

In the 333 years that Vasa lay on the bottom of Stockholm harbor (called Stockholms ström, "the Stream", in Swedish), the ship and its contents were subject to several destructive forces, first among which were decomposition and erosion. Among the first things to decompose were the thousands of iron bolts that held the beakhead and much of the sterncastle together, and this included all of the ship's wooden sculptures. Almost all of the iron on the ship rusted away within a few years of the sinking, and only large objects, such as anchors, or items made of cast iron, such as cannonballs, survived. Organic materials fared better in the anaerobic conditions, and so wood, cloth and leather are often in very good condition, but objects exposed to the currents were eroded by the sediment in the water, so that some are barely recognizable.[41] Objects which fell off the hull into the mud after the nails corroded through were well protected, so that many of the sculptures still retain areas of paint and gilding. Of the human remains, most of the soft tissue was quickly consumed by bacteria, fish and crustaceans, leaving only the bones, which were often held together only by clothing, although in one case, hair, nails and brain tissue survived.[42]

The parts of the hull held together by joinery and wooden treenails remained intact for as much as two centuries, suffering gradual erosion of surfaces exposed to the water, unless they were disturbed by outside forces. Eventually the entire sterncastle, the high, aft portion of the ship that housed the officers' quarters and held up the transom, gradually collapsed into the mud with all the decorative sculptures. The quarter galleries, which were merely nailed to the sides of the sterncastle, collapsed fairly quickly and were found lying almost directly below their original locations.[41]

Human activity was the most destructive factor, as the initial salvage efforts, the recovery of the guns, and the final salvage in the 20th century all left their marks. Peckell and Treileben broke up and removed much of the planking of the weather deck to get to the cannons on the decks below. Peckell reported that he had recovered 30 cartloads of wood from the ship; these might have included not just planking and structural details but also some of the sculptures which today are missing, such as the life-size Roman warrior near the bow and the sculpture of Septimius Severus that adorned the port side of the beakhead.[43] Since Vasa lay in a busy shipping channel, ships occasionally dropped anchor over the ship, and one large anchor demolished most of the upper sterncastle, probably in the 19th century. Construction work in Stockholm harbor usually results in blasting of bedrock, and the resulting tonnes of rubble were often dumped in the harbor; some of this landed on the ship, causing further damage to the stern and the upper deck.[44]

Vasa rediscovered

In the early 1950s, amateur archaeologist Anders Franzén considered the possibility of recovering wrecks from the cold brackish waters of the Baltic because, he reasoned, they were free from the shipworm Teredo navalis, which usually destroys submerged wood rapidly in warmer, saltier seas. Franzén had previously been successful in locating wrecks such as Riksäpplet and Lybska Svan, and after long and tedious research he began looking for Vasa as well. He spent many years probing the waters without success around the many assumed locations of the wreckage. He did not succeed until, based on accounts of an unknown topographical anomaly just south of the Gustav V dock on Beckholmen, he narrowed his search. In 1956, with a home-made, gravity-powered coring probe, he located a large wooden object almost parallel to the mouth of dock on Beckholmen. The location of the ship received considerable attention, even if the identification of the ship could not be determined without closer investigation. Soon after the announcement of the find, planning got underway to determine how to excavate and raise Vasa. The Swedish Navy was involved from the start, as were various museums and the National Heritage board, representatives of which eventually formed the Vasa Committee, the predecessor of the Vasa Board.[45]

Recovery

A number of possible recovery methods were proposed, including filling the ship with ping-pong balls and freezing it in a block of ice, but the method chosen by the Vasa Board (which succeeded the Vasa Committee) was essentially the same one attempted immediately after the sinking. Divers spent two years digging six tunnels under the ship for steel cable slings, which were taken to a pair of lifting pontoons at the surface. The work under the ship was extremely dangerous, requiring the divers to cut tunnels through the clay with high-pressure water jets and suck up the resulting slurry with a dredge, all while working in total darkness with hundreds of tonnes of mud-filled ship overhead.[46] A persisting risk was that the wreck could shift or settle deeper into the mud while a diver was working in a tunnel, trapping him underneath the wreckage. The almost vertical sections of the tunnels near the side of the hull could also potentially collapse and bury a diver inside.[47] Despite the dangerous conditions, more than 1,300 dives were made in the salvage operation without any serious accidents.[48]

Each time the pontoons were pumped full, the cables tightened and the pontoons were pumped out, the ship was brought a metre closer to the surface. In a series of 18 lifts in August and September 1959, the ship was moved from depth of 32 metres (105 ft) to 16 metres (52 ft) in the more sheltered area of Kastellholmsviken, where divers could work more safely to prepare for the final lift.[49] Over the course of a year and a half, a small team of commercial divers cleared debris and mud from the upper decks to lighten the ship, and made the hull as watertight as possible. The gun ports were closed by means of temporary lids, a temporary replacement of the collapsed sterncastle was constructed, and many of the holes from the iron bolts that had rusted away were plugged. The final lift began on 8 April 1961, and on the morning of 24 April, Vasa was ready to return to the world for the first time in 333 years. Press from all over the world, television cameras, 400 invited guests on barges and boats, and thousands of spectators on shore watched as the first timbers broke the surface. The ship was then emptied of water and mud and towed to the Gustav V dry dock on Beckholmen, where the ship was floated on its own keel onto a concrete pontoon, on which the hull still stands.[50]

From the end of 1961 to December 1988, Vasa was housed in a temporary facility called Wasavarvet ("The Vasa Shipyard"), which included exhibit space as well as the activities centred on the ship. A building was erected over the ship on its pontoon, but it was very cramped, making conservation work awkward. Visitors could view the ship from just two levels, and the maximum viewing distance was in most places only a couple of metres, which made it difficult for viewers to get an overall view of the ship. In 1981, the Swedish government decided that a permanent building was to be constructed, and a design competition was organised. The winning design, by the Swedish architects Månsson and Dahlbäck, called for a large hall over the ship in a polygonal, industrial style. Ground was broken in 1987, and Vasa was towed into the half-finished Vasa Museum in December 1988. The museum was officially opened to the public in 1990.[51]

Archaeology

Vasa posed an unprecedented challenge for archaeologists. Never before had a four-storey structure, with most of its original contents largely undisturbed, been available for excavation.[52] The conditions under which the team had to work added to the difficulties. The ship had to be kept wet in order that it not dry out and crack before it could be properly conserved. Digging had to be performed under a constant drizzle of water and in a sludge-covered mud that could be more than one metre deep. In order to establish find locations, the hull was divided into several sections demarcated by the many structural beams, the decking and by a line drawn along the centre of the ship from stern to bow. For the most part, the decks were excavated individually, though at times work progressed on more than one deck level simultaneously.[53]

Finds

Vasa had four preserved decks: the upper and lower gun decks, the hold and the orlop. Because of the constraints of preparing the ship for conservation, the archaeologists had to work quickly, in 13-hour shifts during the first week of excavation. The upper gun deck was greatly disturbed by the various salvage projects between 1628 and 1961, and it contained not only material that had fallen down from the rigging and upper deck, but also more than three centuries of harbor refuse.[54] The decks below were progressively less disturbed. The gundecks contained not just gun carriages, the three surviving cannons, and other objects of a military nature, but were also where most of the personal possessions of the sailors had been stored at the time of the sinking. These included a wide range of loose finds, as well as chests and casks with spare clothing and shoes, tools and materials for mending, money (in the form of low-denomination copper coins), privately purchased provisions, and all of the everyday objects needed for life at sea. Most of the finds are of wood, testifying not only to the simple life on board, but to the generally unsophisticated state of Swedish material culture in the early 17th century. The lower decks were primarily used for storage, and so the hold was filled with barrels of provisions and gunpowder, coils of anchor cable, iron shot for the guns, and the personal possessions of some of the officers. On the orlop deck, a small compartment contained six of the ship's ten sails, rigging spares, and the working parts for the ship's pumps. Another compartment contained the possessions of the ship's carpenter, including a large tool chest.[55]

After the ship itself had been salvaged and excavated, the site of the loss was excavated thoroughly during 1963–1967. This produced many items of rigging tackle as well as structural timbers that had fallen off, particularly from the beakhead and sterncastle. Most of the sculptures that had decorated the exterior of the hull were also found in the mud, along with the ship's anchors and the skeletons of at least four people. The last object to be brought up was the nearly 12-metre-long longboat, called esping in Swedish, found lying parallel to the ship and believed to have been towed by Vasa when it sank.[56]

Many of the more recent objects contaminating the site were disregarded when the finds were registered, but some were the remains of the 1660s salvage efforts and others had their own stories to tell. Among the best known of these was a statue of 20th-century Finnish runner Paavo Nurmi, which was placed on the ship as a prank by students of Helsinki University of Technology (now known as Aalto University) the night before the final lift.[57][58] The inspiration for the hack was that Sweden had forbidden Nurmi from competing in the 1932 Summer Olympics in Los Angeles, United States.

Causes of sinking

Vasa sank because it had very little initial stability, which can be thought of as resistance to heeling over under the force of wind or waves acting on the hull. The reason for this is that the distribution of mass in the hull structure and the ballast, guns, provisions, and other objects loaded on board puts too much weight too high in the ship. The centre of gravity is too high, and so it takes very little force to make the ship heel over, and there is not enough righting moment, force trying to make the ship return to an upright position. The reason that the ship has such a high centre of gravity is not due to the guns. These weighed little over 60 tonnes, or about 5% of the total displacement of the loaded ship. This is relatively low weight and should be bearable in a ship this size. The problem is in the hull construction itself. The part of the hull above the waterline is too high and too heavily built in relation to the amount of hull in the water. The headroom in the decks is higher than necessary for crewmen who were, on average, only 1.67 metres (5 feet 5½ inches) tall, and thus the weight of the decks and the guns they carry is higher above the waterline than needed. In addition, the deck beams and their supporting timbers are over-dimensioned and too closely spaced for the loads they carry, so they contribute too much weight to the already tall and heavy upper works.[59]

The use of different measuring systems on either side of the vessel caused its mass to be distributed asymmetrically, heavier to port. During construction both Swedish feet and Amsterdam feet were in use by different teams. Archaeologists have found four rulers used by the workmen who built the ship. Two were calibrated in Swedish feet, which had 12 inches, while the other two measured Amsterdam feet, which had 11 inches.[60]

Although the mathematical tools for calculating or predicting stability were still more than a century in the future, and 17th-century scientific ideas about how ships behaved in water were deeply flawed, the people associated with building and sailing ships for the Swedish navy were very much aware of the forces at work and their relationships to each other. In the last part of the inquest held after the sinking, a group of master shipwrights and senior naval officers were asked for their opinions about why the ship sank. Their discussion and conclusions show very clearly that they knew what had happened, and their verdict was summed up very clearly by one of the captains, who said that the ship did not have enough "belly" to carry the heavy upperworks.[61]

Common practice of the time dictated that heavy guns were to be placed on the lower gun deck to decrease the weight on the upper gun deck and improve stability. The armament plans were changed many times during the build to either 24-pounders on the lower deck along with lighter 12-pounders on the upper deck or 24-pounders on both decks. The gun ports on the upper deck were the correct size for 12-pounders, but in the end the ship was finished with the heavy 24-pounders on both decks, and this may have contributed to poor stability.[62]

Vasa might not have sunk on 10 August 1628, if the ship had been sailed with the gunports closed. Ships with multiple tiers of gunports normally had to sail with the lowest tier closed, since the pressure of wind in the sails would usually push the hull over until the lower gunport sills were under water. For this reason, the gunport lids are made with a double lip which is designed to seal well enough to keep out most of the water. Captain Söfring Hansson had ordered the lower gundeck ports closed once the ship began to take on water, but by then it was too late. If he had done it before he sailed, Vasa might not have sunk on that day.[61]

Conservation

Although Vasa was in surprisingly good condition after 333 years at the bottom of the sea, it would have quickly deteriorated if the hull had been simply allowed to dry. The large bulk of Vasa, over 600 cubic metres (21,000 cu ft) of oak timber, constituted an unprecedented conservation problem. After some debate on how to best preserve the ship, conservation was carried out by impregnation with polyethylene glycol (PEG), a method that has since become the standard treatment for large, waterlogged wooden objects, such as the 16th-century English ship Mary Rose. Vasa was sprayed with PEG for 17 years, followed by a long period of slow drying, which is not yet entirely complete.[63]

The reason that Vasa was so well-preserved was not just that the shipworm that normally devours wooden ships was absent but also that the water of Stockholms ström was heavily polluted until the late 20th century. The highly toxic and hostile environment meant that even the toughest microorganisms that break down wood had difficulty surviving. This, along with the fact that Vasa had been newly built and was undamaged when it sank, contributed to her conservation. Unfortunately, the properties of the water also had a negative effect. Chemicals present in the water around Vasa had penetrated the wood, and the timber was full of the corrosion products from the bolts and other iron objects which had disappeared. Once the ship was exposed to the air, reactions began inside the timber that produced acidic compounds. In the late 1990s, spots of white and yellow residue were noticed on Vasa and some of the associated artefacts. These turned out to be sulfate-containing salts that had formed on the surface of the wood when sulfides reacted with atmospheric oxygen. The salts on the surface of Vasa and objects found in and around it are not a threat themselves (even if the discolouring may be distracting), but if they are from inside the wood, they may expand and crack the timber from inside. As of 2002, the amount of sulfuric acid in Vasa's hull was estimated to be more than 2 tonnes, and more is continually being created. Enough sulfides are present in the ship to produce another 5,000 kilograms (11,000 lb) of acid at a rate of about 100 kilograms (220 lb) per year; this might eventually destroy the ship almost entirely.[64]

While most of the scientific community considers that the destructive substance responsible for Vasa's long-term decay is sulfuric acid, Ulla Westermark, professor of wood technology at Luleå University of Technology, has proposed another mechanism with her colleague Börje Stenberg. Experiments done by Japanese researchers show that treating wood with PEG in an acidic environment can generate formic acid and eventually liquify the wood. Vasa was exposed to acidic water for more than three centuries, and therefore has a relatively low pH. Samples taken from the ship indicate that formic acid is present, and that it could be one of the multiple causes of a suddenly accelerated rate of decomposition.[65]

The museum is constantly monitoring the ship for damage caused by decay or warping of the wood. Ongoing research seeks the best way to preserve the ship for future generations and to analyze the existing material as closely as possible. A current problem is that the old oak of which the ship is built has lost a substantial amount of its original strength and the cradle that supports the ship does not match up very well with the distribution of weight and stress in the hull. "The amount of movement in the hull is worrying. If nothing is done, the ship will most likely capsize again", states Magnus Olofson from the Vasa Museum. An effort to secure Vasa for the future is under way, in cooperation with the Royal Institute of Technology and other institutions around the globe.[66]

To deal with the problem of the inevitable deterioration of the ship, the main hall of the Vasa Museum is kept at a temperature of 18–20 °C (64–68 °F) and a humidity level of 53%. To slow the destruction by acidic compounds, different methods have been tried. Small objects have been sealed in plastic containers filled with an inert atmosphere of nitrogen gas, for halting further reactions between sulfides and oxygen. The ship itself has been treated with cloth saturated in a basic liquid to neutralise the low pH, but this is only a temporary solution as acid is continuously produced. The original bolts rusted away after the ship sank but were replaced with modern ones that were galvanised and covered with epoxy resin. Despite this, the newer bolts also started to rust and were releasing iron into the wood, which accelerated the deterioration.[67]

Legacy

Vasa has become a popular and widely recognised symbol for a historical narrative about the Swedish stormaktstiden ("the Great Power-period") in the 17th century, and about the early development of a European nation state. Within the disciplines of history and maritime archaeology the wrecks of large warships from the 16th, 17th and 18th centuries have received particularly widespread attention as perceived symbols of a past greatness of the state of Sweden. Among these wrecks, Vasa is the single best known example, and has also become recognised internationally, not least through a deliberate use of the ship as a symbol for marketing Sweden abroad. The name Vasa has in Sweden become synonymous with sunken vessels that are considered to be of great historical importance, and these are usually described, explained and valued in relation to Vasa itself.[68] The Swedish maritime archaeologist Carl-Olof Cederlund, who has been active in the various Vasa-projects, has described the phenomenon as regalskepps-syndromet, "the royal ship syndrome" (after the term used in the 17th century for the largest warships in the Swedish navy). He associates the "syndrome" to a nationalist aspect of the history of ideas and traditional perceptions about hero-kings and glory through war. The focus of this historical theory lies on the "great periods" in "our [Swedish] history" and shares many similarities with the nationalist views of the Viking era in the Nordic countries and the praising of Greek and Roman Antiquity in the Western world in general.[69] Cederlund has stressed the ritualised aspects of the widely publicised salvage in 1961 and has compared the modern Vasa Museum with "a temple in the Classical sense of the word". The placement of the museum on Djurgården, traditional crown property, and its focus on "the King's ship" has led him to suggest a description of it as "The Temple of the Royal Ship".[70]

Literature and popular culture

Vasa's unique status has drawn considerable attention and captured the imagination of more than two generations of scholars, tourists, model builders, and authors. Though historically unfounded, the popular perception of the building of the ship as a botched and disorganised affair (dubbed "the Vasa-syndrome") has been used by many authors of management literature as an educational example of how not to organise a successful business.[lower-alpha 2] In The Tender Ship, Manhattan Project engineer Arthur Squires used the Vasa story as an opening illustration of his thesis that governments are usually incompetent managers of technology projects.[71]

The Vasa Museum has co-sponsored two versions of a documentary about the history and recovery of the ship, both by documentary filmmaker Anders Wahlgren. The second version is currently shown in the museum and has been released on VHS and DVD with narration in 16 languages. In late 2011, a third Vasa-film premiered on Swedish television, with a longer running time and a considerably larger budget (with over 7.5 million kronor provided by SVT).[72] An educational computer game, now in its second generation, has been made and is used in the museum and on its website to explain the fundamentals of 17th century ship construction and stability. Several mass-produced model kits and countless custom-built models of the ship have been made. In 1991, a 308-tonne pastiche reproduction of the ship was built in Tokyo to serve as a 650-passenger sightseeing ship. Vasa has inspired many works of art, including a gilded Disney-themed parody of the pilaster sculptures on the ship's quarter galleries.[73] Being a popular tourist attraction, Vasa is used as a motif for various souvenir products such as T-shirts, mugs, refrigerator magnets, and posters. Commercially produced replicas—such as drinking glasses, plates, spoons, and even a backgammon game—have been made from many of the objects belonging to the crew or officers found on the ship.[74]

See also

- Archaeology of shipwrecks

- Batavia

- Götheborg

- Kronan

- Mars

- HMS Royal George

- List of world's largest wooden ships

Notes

- The original name of the ship was Vasen ("the fascine"), after the heraldic symbol on the coat of arms of the House of Vasa, which was also part of the coat of arms of Sweden at the time. Vasa has since become the most widely recognised name of the ship, largely because the Vasa Museum chose this form of the name as its 'official' orthography in the late 1980s. This spelling was adopted because it is the form preferred by modern Swedish language authorities, and conforms to the spelling reforms instituted in Sweden in the early 20th century.

- For example this article from IEEE computing: Richard E. Fairley, Mary Jane Willshire, "Why the Vasa Sank: 10 Problems and Some Antidotes for Software Projects," IEEE Software vol. 20, no. 2, pp. 18–25, March/April 2003; see also Hocker in Cederlund (2006), p. 58.

References

- "Vasa in Numbers, Vasa Museum

- Schantz, P. 2006. The Formation of National Urban Parks: a Nordic Contribution to Sustainable Development? In: The European City and Green Space; London, Stockholm, Helsinki and S:t Petersburg, 1850–2000 (Ed. Peter Clark), Historical Urban Studies Series (Eds. Jean-Luc Pinol & Richard Rodger), Ashgate Publishing Limited, Aldershot, pp. 159–174.

- 11 million at Wasavarvet 1961–88 and 18 million at the permanent museum since 1990. The total is based on statistics from the official website of the Vasa Museum: (in Swedish) "Museets besökare" Archived 14 August 2010 at the Wayback Machine, 2011; "Vasas sista färd" Archived 18 August 2010 at the Wayback Machine, 2000(?).

- https://www.vasamuseet.se/en

- Hocker in Cederlund (2006), pp. 36–39; see also Jan Glete's paper The Swedish fiscal-military state and its navy, 1521–1721.

- Roberts (1953–58)

- Hocker in Cederlund (2006), p. 47.

- Hocker (2011), p. 147

- Vasa was actually never referred to as a regalskepp before it was lost, but was classified as one afterwards; Hocker (2011), pp. 147–48.

- Hocker in Cederlund (2006), p. 39; for more on Äpplet, see (in Swedish) Jan Glete, "Gustav II Adolfs Äpplet" in Marinarkeologisk tidskrift nr 4, 2002.

- Sandström (1982)

- Hocker in Cederlund (2006), pp. 43–44.

- Hocker in Cederlund (2006), p. 41.

- Hocker (2011), p. 94.

- Hocker in Cederlund (2006), pp. 47–50.

- Hocker in Cederlund (2006), p. 53.

- Hocker in Cederlund (2006), pp. 45–46.

- Hocker (2011), pp. 39–41.

- Fred Hocker in Cederlund (2006), p. 51

- Hocker in Cederlund (2006), p. 49.

- The guns facing fight aft, the stern chasers, were still not on board when the ship sank, however; Hocker (2011) pp. 58–59

- Hocker in Cederlund (2006), pp. 47–51.

- See sample from Smitheman's website here .

- Soop (1986), pp. 20–21.

- Before being crowned as king, Charles had been duke of Södermanland, whose coat of arms include a griffin segreant, standing with its front legs raised; Soop (1986), pp. 18–27.

- Soop (1986), pp. 241–253.

- Soop (1986), p. 247.

- Quotes from Soop (1986), p. 252.

- Soop, pp. 241–253

- Hocker in Cederlund (2006), pp. 53–54.

- Kvarning (1998), pp. 25–35.

- Kvarning (1998), pp. 29–35; Hocker in Cederlund (2006); pp. 55–60.

- Hocker in Cederlund (2006), p. 36.

- Kvarning (1998), pp. 25–32.

- Hafström in Cederlund (2006), p. 69.

- Willis, Sam (2013). Shipwreck: A History of Disasters at Sea. Quercus. p. 54. ISBN 978-1-78206-522-7.

- Hafström in Cederlund (2006), pp. 98–104.

- Hafström in Cederlund (2006), pp. 88–89.

- Cederlund in Cederlund (2006), pp. 142–143.

- Hocker & Wendel in Cederlund (2006), pp. 153–170.

- Hocker in Cederlund (2006), p. 146–152.

- Hocker in Cederlund (2006), p. 154.

- Hocker in Cederlund (2006), pp. 151–152.

- Vasa I, Cederlund and Hocker, pp. 172–180

- Cederlund in Cederlund (2006), pp. 234–244.

- Cederlund in Cederlund (2006), p. 252.

- Kvarning (1998), pp. 61–69.

- Kvarning (1998), p. 69.

- Cederlund in Cederlund (2006), pp. 285–290.

- Kvarning (1998), pp. 163–173.

- Cederlund & Hocker in Cederlund (2006), p. 298.

- Cederlund & Hocker in Cederlund (2006), p. 300.

- Cederlund in Cederlund (2006), p. 315.

- Cederlund & Hocker in Cederlund (2006), pp. 302–305; for the item catalog, see this link Archived 16 October 2007 at the Wayback Machine.

- Cederlund in Cederlund (2006), pp. 470–472.

- "Vasan Veijarit" (in Finnish). Ilta-Sanomat. 5 July 1961. Archived from the original on 13 July 2004. Retrieved 8 December 2007.

- "Teekkarien kuningasjäynästä puoli vuosisataa" [Half a century after the famous hack by the University of Technology students] (in Finnish). Yle. 28 April 2011. Retrieved 19 February 2016.

- Hocker (2011), pp. 132–134.

- "New Clues Emerge in Centuries-Old Swedish Shipwreck". Public Radio International. 23 February 2012.

- Hocker (2011), pp. 135–137.

- Hocker in Cederlund (2006), p. 51.

- Hocker (2011), pp. 192–193.

- Dal & Hall Roth (2002), pp. 38–39.

- (in Swedish) Gothenburg University TV, Vetenskapslandet Archived 30 April 2009 at the Wayback Machine. Aired 5 October 2005. Retrieved 4 March 2009.

- (in Swedish) Dahlquist, Hans. "KTH räddar Vasa från att kantra". Ny Teknik on 19 July 2007. Retrieved 18 December 2007 (archived 22 June 2007 at the Wayback Machine).

- Dal & Hall Roth, pp. 39–41; Sandstrom, M., Jalilehvand, F., Persson, I., Gelius, U., Frank, P., Hall Roth, I. (2002) "Deterioration of the seventeenth-century warship Vasa by internal formation of sulphuric acid", Nature 415 (6874): 893–7.

- Cederlund (1997), s. 38

- Cederlund (1997), s. 38–40

- Cederlund (1997), s. 15; original quotes: "ett tempel i klassisk bemärkelse"; "Det Kungliga Skeppets Tempel".

- Squires, Arthur M. (1986). The Tender Ship: Governmental Management of Technological Change. Boston: Birkhäuser. pp. 1–3. ISBN 081763312X.

- Hellekant, Johan, "Historisk film kämpar i motvind" Svenska Dagbladet, 10 July 2011; Linder, Lars, "Vasa 1628" Dagens Nyheter, 27 December 2011.

- Modellen: Vasamodeller från när och fjärran.

- Vasa Museum homepage. Statens maritima museer. Retrieved 3 March 2009. Archived 10 April 2008 at the Wayback Machine

Sources

- (in Swedish) Cederlund, Carl Olof (1997) Nationalism eller vetenskap? Svensk marinarkeologi i ideologisk belysning. ISBN 91-7203-045-3

- Cederlund, Carl Olof (2006) Vasa I, The Archaeology of a Swedish Warship of 1628, series editor: Fred Hocker ISBN 91-974659-0-9

- (in Swedish) Dal, Lovisa and Hall Roth, Ingrid Marinarkeologisk tidsskrift, 4/2002

- Hocker, Fred (2011) Vasa: A Swedish Warship. Medströms, Stockholm. ISBN 978-91-7329-101-9

- Kvarning, Lars-Åke and Ohrelius, Bengt (1998) The Vasa: the Royal Ship ISBN 91-7486-581-1

- Roberts, Michael (1953–58) Gustavus Adolphus: A History of Sweden 1611–1632 (2 vols, 1953, 1958)

- (in Swedish) Sandström, Anders (1982) Sjöstrid på Wasas tid: Wasastudier, nr 9 ISBN 91-85268-15-1

- Soop, Hans (1986) The Power and the Glory: The Sculptures of The Warship Wasa ISBN 91-7402-168-0

- (in Swedish) Modellen: Vasamodeller från när och fjärran (1997), ISBN 91-85268-69-0 (Vasa Museum exhibit catalog)

Further reading

- Franzén, Anders (1974) The Warship Vasa: deep diving and marine archaeology in Stockholm. Norstedt, Stockholm. ISBN 91-1-745002-0

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Vasa (ship, 1627). |

- Official website of the Vasa Museum

- Vasa's revival Report on the Vasa from the University of Miami.

- SVT Play Video clips of the recovery of Vasa (in Swedish).

- The Vasa of 1628 High resolution photos of the Vasa and the 1:10 scale model in the Vasa museum

- Why The Vasa Sank: 10 Lessons Learned

- Virtual tour 360 degrees panoramas of the Vasa Museum

_en2.png.webp)