Baháʼí Faith by continent

| Part of a series on |

| Baháʼí Faith |

|---|

|

The Baháʼí Faith is a religion founded by Baháʼu'lláh in the 19th century Middle East. Baháʼí sources usually estimate the worldwide Baháʼí population to be above 5 million.[1] Most encyclopedias and similar sources estimate between 5 and 6 million Baháʼís in the world in the early 21st century.[2]

The Baháʼí Faith's growing presence across the world can be shown in stages.[3] First the religion originated in Qajar Persia out of the Bábí religion and spread through the middle east and lands directly adjacent from 1844 to c.1892. Then it internationalized to a particular degree when it moved out of Islamic dominant countries and cultures and came to many countries in the West, a period from c.1892 to c.1953. During this period, for example, sixty percent of the British Baháʼí community eventually relocating.[4] And then a significantly internationalized stage of an almost worldwide presence or "global" presence since 1953.[3] This was accomplished by what Baháʼís call "pioneering". The major program of action being the Ten Year Crusade and the overall list of the first pioneers to countries in the Knights of Baháʼu'lláh – the last being in July 1989 when the religion entered Mongolia.[5]

The religion is almost entirely contained in a single, organized, hierarchical community, but the Baháʼí population has spread out into almost every country and ethnicity in the world, being recognized as the second-most geographically widespread religion after Christianity.[2][6] See Baháʼí statistics. The only countries with no Baháʼís documented as of 2008 are Vatican City and North Korea.[7] Although it is a destination for pilgrimages. Baháʼí staff in Israel do not teach their faith to Israelis following strict Baháʼí policy.[8][9]

Chronology

Below are dates of the establishment and recognition of National Spiritual Assemblies (NSA) from the Baháʼí point of view. Other than in predominantly Muslim counties, countries where there are no NSAs include where most any religious institution is illegal such as in North Korea. In 2008 there were 184 National Spiritual Assemblies and in 2006, there are 192 United Nations member states.

| Year | Number of NSAs[10][11][12] |

|---|---|

| 1923 | 3 |

| 1936 | 10 |

| 1953 | 12 |

| 1963 | 70 |

| 1973 | 113 |

| 1979 | 125 |

| 1988 | 148 |

| 2001 | 182 |

| 2008 | 184 |

Most of the below list comes from The Baháʼí Faith: 1844–1963.[13]

1923: British Isles, Germany, India

1924: Egypt

1925: United States of America & Canada, Philippines

1931: Iraq

1934: Australia and New Zealand, Persia

1948: Canada

1953: Italy and Switzerland

1956: Central & East Africa, North West Africa, South & West Africa

1957: Alaska; Arabia; New Zealand; North East Asia (Japan), Pakistan, South East Asia; Mexico and the Republics of Central America; The Greater Antilles; The Republics of Brazil, Peru, Colombia, Ecuador and Venezuela; The Republics of Chile, Argentina, Uruguay, Paraguay & Bolivia; Scandinavia and Finland; the Benelux Countries; The Iberian Peninsula.

1958: France

1959: Austria, Burma, South Pacific, Turkey,

1961: Bolivia, Chile, Colombia, Costa Rica, Cuba, Dominican Republic, Ecuador, El Salvador, Guatemala, Haiti, Honduras, Jamaica, Mexico, Nicaragua, Panama, Paraguay, Peru, Uruguay, Venezuela, Brazil, Argentina.

1962: Belgium, Ceylon, Denmark, Finland, Netherlands, Luxembourg, Norway, Portugal, Spain, Sweden, Switzerland, Italy, Switzerland

1964: Korea, Thailand, Vietnam

1967: Gilbert and Ellice Islands, Laos, Belize, Sikkim[14]

1969: Papua New Guinea

1972: Singapore, Guyana

1974: Hong Kong, South East Arabia[15]

1975: Niger[10]

1977: Greece

1978: Burundi, Mauritania, the Bahamas, Oman, Qatar, the Mariana Islands, Cyprus[16]

1980: Transkei

1981: Namibia, and Bophuthatswana; the Leeward Islands, the Windward Islands, and Bermuda; Tuvalu. re-formation in Uganda[17]

1984: Cape Verde Islands, Equatorial Guinea, Gabon, French Guiana, Grenada, Martinique, Andaman & Nicobar Islands, Yemen, Canary Islands

1990: Macau[18]

1991: Czechoslovakia, Romania & Soviet Union

1992: Greenland, Azerbaijan, Ukraine, Belarus & Moldova; Russia, Georgia & Armenia; Central Asia, Bulgaria, Baltic States, Albania, Poland, Hungary, Niger (re-elected) (as many new NSAs came into existence in this one year as all the NSAs that existed in 1953.)[19]

1994: Cambodia, Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan, Mongolia, Tajikistan, Uzbekistan, Slovenia & Croatia,

1995: Eritrea, Armenia, Georgia, Belarus, Sicily.

1996: Sao Tome & Principe, Moldova, Nigeria[20]

1999: Latvia, Lithuania, Macedonia

2004: Iraq reformed[21]

2008: Vietnam reformed[22]

Africa

The Baháʼí Faith in Africa marks moment when most of the leading figures of the religion were present on the continent. Among its earliest contacts with the religion came in Egypt. The Baháʼí Faith in Egypt begins perhaps with the first Baháʼís arriving in 1863.[23] Baháʼu'lláh, founder of the religion, was himself briefly in Egypt in 1868 when on his way to imprisonment in ʻAkká.[24]

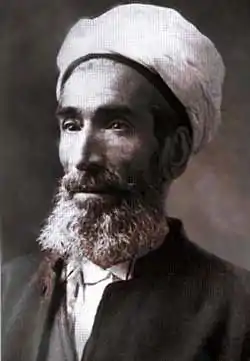

Mírzá Abu'l-Faḍl-i-Gulpáygání, often called Mírzá Abu'l-Faḍl, was the first prominent Baháʼí to live in Africa and made some of the first big changes to the community in Egypt. Abdu'l-Fadl first came to Cairo in 1894 where he settled for several years. He was the foremost Baháʼí scholar and helped spread the Baháʼí Faith in Egypt, Turkmenistan, and the United States.[25][26] In Egypt, he was successful in converting some thirty of the students of Al-Azhar University, the foremost institution of learning in the Sunni Muslim world.[25]

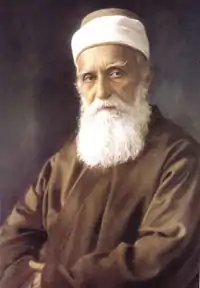

ʻAbdu'l-Bahá, head of the religion after Baháʼu'lláh, lived in Egypt for several years and several people came to meet him there: Stanwood Cobb,[27] Wellesley Tudor Pole,[28] Isabella Grinevskaya,[29] and Louis George Gregory, later the first Hand of the Cause of African descent, visited ʻAbdu'l-Bahá at Ramleh in 1911.[23] ʻAbdu'l-Bahá then embarked on several trips to the West taking an ocean liner for the first one on 11 August 1911.[30] He left on the next trip left 25 March 1912.[31] One of the earliest Baháʼís of the west and a Disciple of ʻAbdu'l-Bahá, Lua M. Getsinger, died in 1916 and she was buried in Egypt[32] near Mírzá Abu'l-Faḍl.

ʻAbdu'l-Bahá wrote a series of letters, or tablets, to the followers of the religion in the United States in 1916–1917; these letters were compiled together in the book Tablets of the Divine Plan. The eighth and twelfth of the tablets mentioned Africa and were written on 19 April 1916 and 15 February 1917, respectively. Publication however was delayed in the United States until 1919 – published in Star of the West magazine on 12 December 1919.[33] ʻAbdu'l-Bahá mentions Baháʼís traveling "…especially from America to Europe, Africa, Asia and Australia, and travel through Japan and China. Likewise, from Germany teachers and believers may travel to the continents of America, Africa, Japan and China; in brief, they may travel through all the continents and islands of the globe"[34] and " …the anthem of the oneness of the world of humanity may confer a new life upon all the children of men, and the tabernacle of universal peace be pitched on the apex of America; thus Europe and Africa may become vivified with the breaths of the Holy Spirit, this world may become another world, the body politic may attain to a new exhilaration…."[35]

Shoghi Effendi, who was appointed the leader of the religion after ʻAbdu'l-Bahá's death, travelled through Africa in 1929 and again in 1940 on personal trips.[36]

At the other extreme of the continent the Baháʼí Faith in South Africa struggled with issues under the segregated social pattern and laws of Apartheid in South Africa. The Baháʼí community decided that instead of dividing the South African Baháʼí community into two population groups, one black and one white, they instead limited membership in the Baháʼí administration to black adherents, and placed the entire Baháʼí community under the leadership of its black population.[37][38][39] In 1997 the National Spiritual Assembly presented a Statement to the Truth and Reconciliation Commission of South Africa which said in part:

Abhorring all forms of prejudice and rejecting any system of segregation, the Baháʼí Faith was introduced on a one-to-one basis and the community quietly grew during the apartheid years, without publicity. Despite the nature of the politics of that time, we presented our teachings on unity and the oneness of humankind to prominent individuals in politics, commerce and academia and leaders of thought including State Presidents.... [b]oth individual Baháʼís and our administrative institutions were continually watched by the security police.... Our activities did not include opposition to the previous Government for involvement in partisan politics and opposition to government are explicitly prohibited by the sacred Texts of our Faith.... During the time when the previous Government prohibited integration within our communities, rather than divide into separate administrative structures for each population group, we opted to limit membership of the Baháʼí Administration to the black adherents who were and remain in the majority of our membership and thereby placed the entire Baháʼí community under the stewardship of its black membership.... The pursuit of our objectives of unity and equality has not been without costs. The "white" Baháʼís were often ostracized by their white neighbours for their association with "non-whites". The Black Baháʼís were subjected to scorn by their black compatriots for their lack of political action and their complete integration with their white Baháʼí brethren.[37][38][39][40]

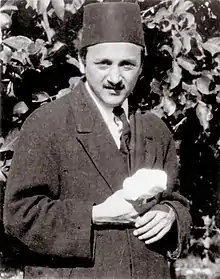

Wide-scale growth in the religion across Sub-Saharan Africa was observed to begin in the 1950s and extend in the 1960s.[41] In 1953 the Baháʼís initiated a Ten Year Crusade during which a number of Baháʼís pioneered to various parts of Africa following the requests of ʻAbdu'l-Bahá.[23][42] It was emphasized that western pioneers be self-effacing and focus their efforts not on the colonial leadership but on the native Africans[43] – and that the pioneers must show by actions the sincerity of their sense of service to the Africans in bringing the religion and then the Africans who understand their new religion were to be given freedom to rise up and spread the religion according to their own sensibilities and the pioneers to disperse or step into the background.[43] Among the figures of the religion in Africa, the most senior African historically would be Enoch Olinga. In 1953, he became the first Baháʼí pioneer to British Cameroon, (moving from Uganda) and was given the title Knight of Baháʼu'lláh for that country.[44] He was appointed as the youngest[45] Hand of the Cause, the highest appointed position in the religion. A biography published in 1984 examined his impact in Cameroon and beyond.[46]

Period since the Universal House of Justice

Troubles characterize the experience of the Baháʼís across the Saharan countries. In 1960, with a regime change in Egypt, the Baháʼís lost all rights as an organized religious community[47] by Law 263[48] at the decree of then-President Gamal Abdel Nasser[49] which specified a minimum sentence of six months' imprisonment or a fine for any organized activities of the Baháʼís.[23] All Baháʼí community properties, including Baháʼí centers, libraries, and cemeteries, were confiscated by the government[48] except the cemetery Al-Rawda Al-Abadeyya.[50] In obedience to the government is a core principal of the religion.[51] In 1963, the arrests of Baháʼís in Morocco had gotten attention from Hassan II of Morocco, US Senator Kenneth B. Keating[52] and Roger Nash Baldwin, then Chairman of the International League for the Rights of Man[42] and would echo in analyses of politics of Morocco for years to come.[53][54]

South of the Sahara, it was a different story. Wide-scale growth in the religion across Sub-Saharan Africa was observed to begin in the 1950s and extend in the 1960s.[41] The foundation stone of the Baháʼí House of Worship in Uganda was laid in January 1958, and it was dedicated on 13 January 1961. The building is more than 130 feet (39 m) high, and over 100 meters in diameter at the base. The green dome is made of fixed mosaic tiles from Italy, and the lower roof tiles are from Belgium. The walls of the temple are of precast stone quarried in Uganda. The colored glass in the wall panels was brought from Germany. The timber used for making the doors and benches was from Uganda. The 50-acre (200,000 m2) property includes the House of Worship, extensive gardens, a guest house, and an administrative center.[55] Hand of the Cause Rúhíyyih Khanum and then chairman of the central regional National Assembly Ali Nakhjavani embarked on 15 days of visiting Baháʼís through Uganda and Kenya including seeing three regional conferences on the progress of the religion, staying in homes of fellow believers, and other events. She talked to audiences about the future of African Baháʼís and their role in the religion.[56] She visited Africa again on several trips from 1969 to 1973.[57] In Ethiopia she was received by Haile Selassie I of Ethiopia.[58] In the half-hour interview, she communicated how she had long admired him because of the way he had conducted himself in the face of the many trials and hardships of his life, and by the way he had overcome them. Selassie gave her a gold medal from his Coronation.[59]

These two regions - North and Central Africa - interacted closely in the 1970s. As part of a sweep across several Sub-Saharan countries, the Baháʼí Faith was banned in the 1970s in several countries: Burundi 1974; Mali 1976;Uganda 1977; Congo 1978; Niger 1978. Uganda had had the largest Baháʼí community in Africa at the time.[60]

"This was principally the result of a campaign by a number of Arab countries. Since these countries were also by this time providers of development aid, this overt attack on the Baha'is was supported by covert moves such as linking the aid money to a particular country to the action that it took against the Baha'is. This was partially successful and a number of countries did ban the Baha'is for a time. However, the Baha'is were able to demonstrate to these governments that they were not agents of Zionism nor anti-Islamic and succeeded in having the ban reversed in all of these countries except Niger."[60] (Niger lifted their restrictions in the 1990s.[61])

More recently, the roughly 2000[50] Baháʼís of Egypt have been embroiled in the Egyptian identification card controversy from 2006[62] through 2009.[63] Since then there have been homes burned down and families driven out of towns.[64] On the other hand, Sub-Saharan Baháʼís were able to mobilize for regional conferences called for by the Universal House of Justice 20 October 2008 to celebrate recent achievements in grassroots community-building and to plan their next steps in organizing in their home areas. Nine such conferences were held.[65]

Asia

The Baháʼí Faith originated in Asia, in Iran (Persia), and spread from there to the Ottoman Empire, Central Asia, India, and Burma during the lifetime of Baháʼu'lláh. Since the middle of the 20th century, growth has particularly occurred in other Asian countries, because the Baháʼí Faith's activities in many Muslim countries has been severely suppressed by authorities.

Estimates for the early 21st century population of Baháʼís in Iran vary between 150,000 and 500,000. During the Iranian Revolution of 1979 and the subsequent few years, a significant number of Baháʼís left the country during intensive persecution.

- Eliz Sanasarian writes in Religious Minorities in Iran (Cambridge University Press, 2000, p. 53) that "Estimating the number of Baháʼís in Iran has always been difficult due to their persecution and strict adherence to secrecy. The reported number of Baháʼís in Iran has ranged anywhere from the outrageously high figure of 500,000 to the low number of 150,000. The number 300,000 has been mentioned most frequently, especially for the mid- to late- 1970s, but it is not reliable. Roger Cooper gives an estimate of between 150,000 and 300,000."

- The Encyclopedia of the Modern Middle East and North Africa (2004) states that "In Iran, by 1978, the Baháʼí community numbered around 300,000."

- The Columbia Encyclopedia (5th edition, 1993) reports that "Prior to the Iranian Revolution there were about 1 million Iranian Baháʼís."

- The Encyclopedia of Islam (new edition, 1960) reports that "In Persia, where different estimates of their number vary from more than a million down to about 500,000. [in 1958]"

At times the authorities in Iran have claimed that there are no Baháʼís in their country, and that the persecutions were made up by the CIA. The first claim apparently represents a legal rather than anthropological determination, as Baháʼís are regarded as Muslims under Iranian law. For the latter, see Persecution of Baháʼís.

The largest Baháʼí community in the world, according to the Baháʼís, is in India, with a population of over 2 million[66] and roots that go back to the first days of the religion in 1844. A Baháʼí researcher, William Garlington, characterized the 1960s until present as a time of "Mass Teaching".[67] He suggests that the mentality of the believers in India changed during the later years of Shoghi Effendi's ministry, when they were instructed to accept converts who were illiterate and uneducated. The change brought teaching efforts into the rural areas of India, where the teachings of the unity of humanity attracted many of the lower caste. The 2011 Census of India recorded only 4,572 Baháʼís.[68]

The Baháʼí Faith in Russia begins with connections during the Russian rule in Azerbaijan in the Russian Empire in the form of the figure of a woman who would play a central role in the religion of the Báb, viewed by Bahá´ís as the direct predecessor of the Baháʼí Faith – she would be later named Tahirih.[69] While the religion spread across the Russian Empire[70][71] and attracted the attention of scholars and artists,[72] the Baháʼí community in Ashgabat built the first Baháʼí House of Worship, elected one of the first Baháʼí local administrative institutions and was a center of scholarship. During the period of the Soviet Union Russia adopted the Soviet policy of oppression of religion, so the Baháʼís, strictly adhering to their principle of obedience to legal government, abandoned its administration and properties[73] but in addition Baháʼís across the Soviet Union were sent to prisons and camps or abroad.[74] Before the Dissolution of the Soviet Union Baháʼís in several cities were able to gather and organize as Perestroyka approached from Moscow through many Soviet republics.[69] The National Assembly of the Russian Federations was ultimately formed in 1995.[75]

Baháʼís are noted in most of the rest of the countries of Asia.

Central America

ʻAbdu'l-Bahá, the son of the founder of the religion, wrote a series of letters, or tablets, to the followers of the religion in the United States in 1916–1917; these letters were compiled together in the book titled Tablets of the Divine Plan. The sixth of the tablets was the first to mention Latin American regions and was written on 8 April 1916, but was delayed in being presented in the United States until 1919. The first actions on the part of Baháʼí community towards Latin America were that of a few individuals who made trips to Mexico and South America near or before this unveiling in 1919. The sixth tablet was published in Star of the West magazine on 12 December 1919.[76]

His Holiness Christ says: Travel ye to the East and to the West of the world and summon the people to the Kingdom of God.…(travel to) the Islands of the West Indies, such as Cuba, Haiti, Puerto Rico, Jamaica, the Islands of the Lesser Antilles (which includes Barbados), Bahama Islands, even the small Watling Island, have great importance…[77]

In 1927 Leonora Armstrong was the first Baháʼí to visit many of these countries where she gave lectures about the religion as part of her plan to compliment and complete Hand of the Cause Martha Root's unfulfilled intention of visiting all the Latin American countries for the purpose of presenting the religion to an audience.[78]

Seven Year Plan and succeeding decades

Shoghi Effendi, head of the religion after the death of ʻAbdu'l-Bahá in 1921, wrote a cable on 1 May 1936 to the Baháʼí Annual Convention of the United States and Canada, and asked for the systematic implementation of ʻAbdu'l-Bahá's vision to begin.[79] In his cable he wrote:

Appeal to assembled delegates ponder historic appeal voiced by ʻAbdu'l-Bahá in Tablets of the Divine Plan. Urge earnest deliberation with incoming National Assembly to insure its complete fulfillment. First century of Baháʼí Era drawing to a close. Humanity entering outer fringes most perilous stage its existence. Opportunities of present hour unimaginably precious. Would to God every State within American Republic and every Republic in American continent might ere termination of this glorious century embrace the light of the Faith of Baháʼu'lláh and establish structural basis of His World Order.[80]

As far back as 1951 the Baháʼís had organized a regional National Assembly for the combination of Mexico, Central America and the Antilles islands.[79] Many counties formed their own National Assembly in 1961. Others continued to be organized in regional areas growing progressively smaller. From 1966 the region was reorganized among the Baháʼís of Leeward, Windward and Virgin Islands with its seat in Charlotte Amalie.[81]

Among the more notable visitors was Hand of the Cause Ruhiyyih Khanum when she toured many parts of Central America in the 1970s.[82]

The Baháʼí House of Worship in Panama City, Panama, completed 1972. It serves as the mother temple of Latin America. It is perched on a high cliff, "Cerro Sonsonate" ("Singing Hill"), overlooking the city, and is constructed of local stone laid in a pattern reminiscent of Native American fabric designs.

The Association of Religion Data Archives estimated various countries with populations of Baháʼís around a few percent of the national populations.[83]

Europe

In 1910, ʻAbdu'l-Bahá, then head of the Baháʼí Faith, embarked on a three-year journey to Egypt, Europe, and North America, spreading the Baháʼí message.[84]

ʻAbdu'l-Bahá's first European trip spanned from August to December 1911, at which time he returned to Egypt. During his first European trip he visited Lake Geneva on the border of France and Switzerland, Great Britain and Paris, France. The purpose of these trips was to support the Baháʼí communities in the West and to further spread his father's teachings,[85] after sending representatives and a letter to the First Universal Races Congress in July.[86][87]

His first touch on European soil was in Marseille, France.[88] From then he went to Great Britain.

During his travels, he visited England in the autumn of 1911. On 10 September he made his first public appearance before an audience at the City Temple, London, with the English translation spoken by Wellesley Tudor Pole.[89][90]

ʻAbdu'l-Bahá arrived in Liverpool on 13 December,[91] and over the next six months he visited Britain, France, Austria-Hungary, and Germany before finally returning to Egypt on 12 June 1913.[85]

Starting in 1946 Shoghi Effendi, head of the religion after the death of ʻAbdu'l-Bahá, drew up plans for the American (US and Canada) Baháʼí community to send pioneers to Europe; the Baháʼís set up a European Teaching Committee chaired by Edna True.[92] At a follow-up conference in Stockholm in August 1953, Hand of the Cause Dorothy Beecher Baker asked for a Baháʼí to settle in Europe. By 1953 many had. Soon many national assemblies reformed. Baháʼís had managed to re-enter various countries of the Eastern Bloc to a limited degree.[70]

Meanwhile, in Turkey by the late 1950s Baháʼí communities existed across many of the cities and towns Baháʼu'lláh passed through on his passage through the country.[93] In 1959 the Baháʼí National Spiritual Assembly of Turkey was formed with the help of ʻAlí-Akbar Furútan, a Hand of the Cause — an individual considered to have achieved a distinguished rank in service to the religion.[94][95] However repeating the pattern of arrests in the 20s and 30s, in 1959 there was a mass arrest of the local assembly of Ankara.[93]

In 1962 in Religion in the Soviet Union, Walter Kolarz notes:

"Islam…is attacked by the communists because it is 'reactionary', encourages nationalist narrowmindness and obstructs the education and emancipation of women. Baha'iism(sic) has incurred communist displeasure for exactly the opposite reasons. It is dangerous to Communism because of its broadmindness, its tolerance, its international outlook, the attention it pays to women's education and its insistence on equality of the sexes. All this contradicts the communist thesis about the backwardness of all religions."[96]

First Baháʼí World Congress

In 1963 the British community hosted the first Baháʼí World Congress. It was held in the Royal Albert Hall and chaired by Hand of the Cause Enoch Olinga, where approximately 6,000 Baháʼís from around the world gathered.[97][98] It was called to commemorate the hundredth anniversary of the declaration of Baháʼu'lláh, and announce and present the election of the first members of the Universal House of Justice with the participation of over 50 National Spiritual Assemblies' members from around the world.

Rebirth and restriction in the East

While the religion grew in Western Europe, the Universal House of Justice, the head of the religion since 1963, then recognized small Baháʼí presence across the USSR of about 200 Baháʼís.[99] As Perestroyka approached, the Baháʼís began to organize and get in contact with each other.

Before the Dissolution of the Soviet Union Baháʼís in several cities were able to gather and organize. In this brief time ʻAlí-Akbar Furútan was able to return in 1990 as the guest of honor at the election of the National Spiritual Assembly of the Baha'is of the Soviet Union.[100] From 1990 to 1997 Baháʼís had operated in some freedom, growing to 20 groups of Baháʼís registered with the federal government, but the Law on Freedom of Conscience and Religious Associations passed in 1997 is generally seen as unfriendly to minority religions though it hasn't frozen further registrations.[101] Conditions are generally similar or worse in other post-Soviet countries.

North America

In the United States, hosting one of the most prominent Baháʼí communities, the estimate in Feb 2011 was 169,130 members on record, excluding Alaska and Hawaii.

In 1894 Thornton Chase became the first North American Baháʼí who remained in the faith. By the end of 1894 four other Americans had also become Baháʼís. In 1909, the first National Convention was held with 39 delegates from 36 cities.[102]

ʻAbdu'l-Bahá, then head of the religion, wrote a series of letters, to the followers of the religion in the United States in 1916–1917; these letters were compiled together in the book Tablets of the Divine Plan. The sixth of the tablets was the first to mention Latin American regions and was written on 8 April 1916 and published in Star of the West magazine on 12 December 1919.[103] After mentioning the need for the message of the religion to visit the Latin American countries ʻAbdu'l-Bahá continues:

... becoming severed from rest and composure of the world, [they] may arise and travel throughout Alaska, the republic of Mexico, and south of Mexico in the Central American republics, such as Guatemala, Honduras, El Salvador, Nicaragua, Costa Rica, Panama and Belize...[104]

Following this a few Baháʼís began to move south.[105] Shoghi Effendi, who was named ʻAbdu'l-Bahá's successor, wrote a cable on 1 May 1936 to the Baháʼí Annual Convention of the United States and Canada, and asked for the systematic implementation of ʻAbdu'l-Bahá's vision to begin.[79] In his cable he wrote:

"Appeal to assembled delegates ponder historic appeal voiced by ʻAbdu'l-Bahá in Tablets of the Divine Plan. Urge earnest deliberation with incoming National Assembly to insure its complete fulfillment. First century of Baháʼí Era drawing to a close. Humanity entering outer fringes most perilous stage its existence. Opportunities of present hour unimaginably precious. Would to God every State within American Republic and every Republic in American continent might ere termination of this glorious century embrace the light of the Faith of Baháʼu'lláh and establish structural basis of His World Order."[106]

In 1937 the First Seven Year Plan (1937–44), which was an international plan designed by Shoghi Effendi, gave the American Baháʼís the goal of establishing the Baháʼí Faith in every country in Latin America. With the spread of American Baháʼís communities and assemblies began to form in 1938 across Latin America including Mexico and the communities rose to establishing national assemblies in the 1960s.[79]

In 1944 every state in the United States had at least one local Baháʼí administrative body.[107]

The Association of Religion Data Archives estimated the populations of Baháʼís in countries of North America from the tens of thousands and up in 2005.[83]

South America

The Baháʼí Faith was introduced into South America in 1919 when Martha Root made an extended trip to Brazil, Argentina, Chile, and Peru. She introduced the Baháʼí Faith to Esperantists and Theosophical groups and visited local newspapers to ask them to publish articles about the Baháʼí Faith. The first Baháʼí permanently resident in South America was Leonora Armstrong, who arrived in Brazil in 1921. The first Seven Year Plan (1937–44), an international plan organized by then head of the Baháʼí Faith, Shoghi Effendi, gave the American Baháʼís the goal of establishing the Baháʼí Faith in every country in Latin America (that is, settling at least one Baháʼí or converting at least one native). In 1950, the National Spiritual Assembly of the Baháʼís of South America was first elected, and then in 1957 this Assembly was split into two – basically northern/eastern South America with the Republics of Brazil, Peru, Colombia, Ecuador, and Venezuela, in Lima, Peru and one of the western/southern South America with the Republics of Argentina, Chile, Uruguay, Paraguay, and Bolivia in Buenos Aires, Argentina.[108] By 1963, most countries in South America had their own National Spiritual Assembly.

Among the more significant developments across South and Central America for the religion has been the building of the last continental Baháʼí House of Worship in Chile, a program of developing Baháʼí radio stations in several countries, relationships with indigenous populations, development programs like FUNDAEC, and the Ruhi institute process began in Colombia.

Oceania

From Australia across Polynesia throughout Oceania Baháʼís have established communities in the countries and territories of the region.

The Baháʼí Faith in Australia has a long history beginning with a mention by ʻAbdu'l-Bahá, the son of the founder of the religion, in 1916[109] following which United Kingdom/American emigrants John and Clara Dunn came to Australia in 1920.[110]

They found people willing to convert to the Baháʼí Faith in several cities while further immigrant Baháʼís also arrived.[111] The first Local Spiritual Assembly was elected in Melbourne[112] followed by the first election of the National Spiritual Assembly in 1934.[113]

Since the 1980s the Baháʼís of Australia have become involved and spoken out on a number of civic issues – like conferences on indigenous issues[114] and national policies of equal rights and pay for work.[115] Meanwhile, the first mention of the Baháʼí Faith in New Zealand was in 1853[116] continuous contact began around 1904 when one individual after another came in contact with Baháʼís and some of them published articles in print media in New Zealand as early as 1908.[117] The first Baháʼí in the Antipodes was Dorothea Spinney who had just arrived from New York in Auckland in 1912.[118] After ʻAbdu'l-Bahá wrote the Tablets of the Divine Plan which mentions New Zealand[119] the community grew quickly so that the first Baháʼí Local Spiritual Assembly of the country was attempted in 1923[120] or 1924[121] and then succeeded in 1926. The Baháʼís of New Zealand elected their first independent National Spiritual Assembly in 1957.[122]

The Baháʼí Faith in (Western) Samoa and American Samoa begins with the then head of the religion, ʻAbdu'l-Bahá, mentioning the islands in 1916.[123] This inspired Baháʼís on their way to Australia in 1920 to stop in Samoa.[124] Thirty four years later another Baháʼí from Australia pioneered to Samoa in 1954.[125] With the first converts the first Baháʼí Local Spiritual Assembly was elected in 1961,[126] and the Baháʼí National Spiritual Assembly was first elected in 1970. Following the conversion of the then Head of State of Samoa, King Malietoa Tanumafili II,[127] the first Baháʼí House of Worship of the Pacific Islands was finished in 1984 and the Baháʼí community reached a population of over 3000 in about the year 2000.[128]

Baháʼís have gone on to raise up communities in the island nations across the Southern Pacific.[83]

See also

- Category:Bahá'í Faith by country

- Baháʼí Faith and Native Americans

- Baháʼí statistics

- Religions by country

- Islam by country

- Ahmadiyya by country

- Judaism by country

- Hinduism by country

- Christianity by country

- Sikhism by country

- Irreligion by country

Notes

- Baháʼí International Community (2006). "Worldwide Community". Baháʼí International Community. Archived from the original on 13 June 2006. Retrieved 31 May 2006.

- Encyclopædia Britannica (2002). "Worldwide Adherents of All Religions by Six Continental Areas, Mid-2002". Encyclopædia Britannica. Encyclopædia Britannica.

- Smith, Peter (December 2014). Carole M. Cusack; Christopher Hartney (eds.). "The Baha'i Faith: Distribution Statistics, 1925–1949". Journal of Religious History. 39 (3): 352–369. doi:10.1111/1467-9809.12207. ISSN 1467-9809.

- U.K. Baháʼí Heritage Site. "The Baháʼí Faith in the United Kingdom – A Brief History". Archived from the original on 26 February 2008. Retrieved 18 February 2008.

- "A Brief History of the Baháʼí Faith". Fourth Epoch of the Formative Age: 1986 – 2001. Spiritual Assembly of the Baháʼís of Boise, Idaho, U.S.A. 9 May 2009. Archived from the original on 11 September 2010. Retrieved 12 June 2010.

- MacEoin, Denis (2000). "Baha'i Faith". In Hinnells, John R. (ed.). The New Penguin Handbook of Living Religions (Second ed.). Penguin. ISBN 978-0-14-051480-3.

- Smith, Peter (2008). An Introduction to the Baha'i Faith. Cambridge University Press. pp. 79, 95. ISBN 978-0-521-86251-6.

- Baháʼís did enter Korea in 1921 before the Division of Korea. Sims, Barbara R. (1996). "The First Mention of the Baháʼí Faith in Korea". Raising the Banner in Korea; An Early Baháʼí History. National Spiritual Assembly of the Baháʼís of Korea – via Baháʼí Library Online.

- "The Baháʼí World Centre: Focal Point for a Global Community". The Baháʼí International Community. Archived from the original on 29 June 2007. Retrieved 2 July 2007.

- "Teaching the Faith in Israel". Baháʼí Library Online. 23 June 1995. Retrieved 6 August 2007 – via Baháʼí Library Online.

- Notes on Research on National Spiritual Assemblies Asia Pacific Baháʼí Studies.

- Baha'i World Statistics 2001 by Baha'i World Center Department of Statistics, 2001–08

- The Life of Shoghi Effendi by Helen Danesh, John Danesh and Amelia Danesh, Studying the Writings of Shoghi Effendi, edited by M. Bergsmo (Oxford: George Ronald, 1991)

- The Baháʼí Faith: 1844–1963 Information Statistical and Comparative, Including the Achievements of the Ten Year International Baháʼí Teaching & Consolidation Plan 1953–1963, Compiled by Hands of the Cause Residing in the Holy Land, pages 22 and 46.

- Messages from the Universal House of Justice, 1963–1986: the third epoch of the formative age compiled by Geoffry W. Marks, page 96. ISBN 0-87743-239-2

- Naw Rúz 1974, Baha'i Era 131 by Universal House of Justice

- Ridvan 1978, Baha'i Era 135 by Universal House of Justice

- Ridván 1980, Baha'i Era 137 by Universal House of Justice

- Ridván 1990, Baha'i Era 147 by Universal House of Justice

- Ridván 1992 by the Universal House of Justice

- Letter To all National Spiritual Assemblies by the Universal House of Justice

- Ridvan 2004, Baha'i Era 161 by Universal House of Justice

- "Vietnamese Baha'is reach milestone with election of National Spiritual Assembly". news.bahai.org. Baháʼí World News Service. 4 April 2008. Retrieved 12 June 2015.

- Hassall, Graham (c. 2000). "Egypt: Baha'i history". Asia Pacific Baháʼí Studies: Baháʼí Communities by country. Baháʼí Online Library. Retrieved 24 May 2009 – via Baháʼí Library Online.

- Smith, Peter (2008). An Introduction to the Baha'i Faith. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. p. 26. ISBN 978-0521862516.

- Momen, Moojan (4 March 2002). "Abu'l-Faḍl Gulpaygani, Mirza". Archived from the original on 13 May 2008. Retrieved 19 February 2007.

- Smith, Peter (2000), "Mírzá Abu'l-Faḍl Gulpáygání, Mírzá Muḥammad", A concise encyclopedia of the Baháʼí Faith, Oxford: Oneworld Publications, pp. 22–23, ISBN 978-1-85168-184-6

- "Glimpsing Early Baháʼí Pilgrimages". Baháʼí News. No. 498. October 1972. p. 6.

- Graham Hassall (1 October 2006). "Egypt: Baha'i history". Retrieved 1 October 2006 – via Baháʼí Library Online.

- Hassall, Graham (1993). "Notes on the Babi and Baha'i Religions in Russia and its territories". Journal of Baháʼí Studies. 5 (3): 41–80, 86. doi:10.31581/JBS-5.3.3(1993). Retrieved 20 March 2009 – via Baháʼí Library Online.

- "International Council Reviews Progress in Baha'i World Community". Baháʼí News. No. 369. December 1961. p. 6.

- ʻAbbas, ʻAbdu'l-Bahá (1929). ʻAbdu'l-Bahá in Egypt. Mirza Ahmad Sohrab (trans. and comments) – via Baháʼí Library Online.

- Sears, William; Robert Quigley (1972). The Flame. George Ronald Publisher Ltd. ISBN 9780853980308. Archived from the original on 15 April 2012. Retrieved 30 May 2013.

- ʻAbbas, ʻAbdu'l-Bahá (April 1919). Tablets, Instructions and Words of Explanation. Mirza Ahmad Sohrab (trans. and comments) – via Baháʼí Library Online.

- ʻAbdu'l-Bahá (1991) [1916-17]. Tablets of the Divine Plan (Paperback ed.). Wilmette, IL: Baháʼí Publishing Trust. pp. 47–59. ISBN 978-0877432333.

- ʻAbdu'l-Bahá (1991) [1916-17]. Tablets of the Divine Plan (Paperback ed.). Wilmette, IL: Baháʼí Publishing Trust. pp. 82–89. ISBN 978-0877432333.

- Baháʼí International Community (31 December 2003). "Generation expresses gratitude". BWNS. Baháʼí International Community. Retrieved 19 March 2008.

- Truth and Reconciliation Commission of South Africa Report (29 October 1998). "Regional Profile: Eastern Cape and Appendix: Statistics on Violations in the Eastern Cape" (PDF). Volume Three – Truth and Reconciliation Commission of South Africa Report. Truth and Reconciliation Commission of South Africa Report. pp. 32, 146. Retrieved 19 March 2008.

- National Spiritual Assembly of the Baháʼís of South Africa (19 November 1997). "Statement to the Truth and Reconciliation Commission". Official Webpage. National Spiritual Assembly of the Baháʼís of South Africa. Archived from the original on 29 August 2014. Retrieved 19 March 2008.

- Truth and Reconciliation Commission of South Africa (29 October 1998). "various chapters" (PDF). Volume Four – Truth and Reconciliation Commission of South Africa Report. Truth and Reconciliation Commission of South Africa. paragraphs 6, 27, 75, 84, 102. Retrieved 19 March 2008.

- Reber, Pat (2 May 1999). "Baha'i Church Shooting Verdicts in". South Africa Associated Press. Retrieved 19 March 2008 – via Baháʼí Library Online.

- "Overview of World Religions". General Essay on the Religions of Sub-Saharan Africa. Division of Religion and Philosophy, University of Cumbria. Archived from the original on 9 December 2007. Retrieved 16 April 2008.

- Cameron, G.; Momen, W. (1996). A Basic Baháʼí Chronology. Oxford, UK: George Ronald. pp. 301, 304–5, 306, 308, 328, 329, 331, 354–359, 375, 400, 435, 440–441. ISBN 978-0-85398-404-7.

- "United States Africa Teaching Committee; Goals for this year". Baháʼí News. No. 283. September 1954. pp. 10–11.

- Mughrab, Jan (2004). "Jubilee Celebration in Cameroon" (PDF). Baháʼí Journal of the Baháʼí Community of the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland. 20 (5). National Spiritual Assembly of the Baháʼís of the United Kingdom – via Baháʼí Library Online.

- Lee, Anthony A. (2005). "Enoch Olinga". In Kwame Anthony Appiah; Henry Louis Gates Jr (eds.). Africana: The Encyclopedia of the African and African-American Experience. 1 of 5 (Revised ed.). Oxford University Press. pp. 278–279.

- "Enoch Olinga: The pioneering years". Baháʼí News. No. 638. May 1984. pp. 4–9. ISSN 0195-9212.

- "Baha'i community of Egypt". Official Website of the Baháʼís of Australia. National Spiritual Assembly of the Baháʼís of Australia. Archived from the original on 29 September 2009. Retrieved 24 May 2009.

- U.S. Department of State (15 September 2004). "Egypt: International Religious Freedom Report". Bureau of Democracy, Human Rights, and Labor. Retrieved 20 October 2006.

- U.S. Department of State (26 October 2001). "Egypt: International Religious Freedom Report". Bureau of Democracy, Human Rights, and Labor. Retrieved 28 December 2006.

- El-Hennawy, Noha (September 2006). "The Fourth Faith?". Egypt Today. Archived from the original on 4 September 2009.

- Amnesty International (October 1996). "Dhabihullah Mahrami: Prisoner of Conscience". AI INDEX: MDE 13/34/96. Archived from the original on 23 February 2003. Retrieved 20 October 2006.

- Rabbani, R., ed. (1992). The Ministry of the Custodians 1957–1963. Baháʼí World Centre. pp. 414–419. ISBN 978-0-85398-350-7.

- Cohen, Mark L.; Lorna Hahn (1966). Morocco: old land, new nation. Frederick A. Praeger. pp. 141–146.

- Abdelilah, Bouasria. "The other 'Commander of the faithful': Morocco's King Mohammed VI's religious policy". World Congress for Middle Eastern Studies. European Institute of the Mediterranean. Retrieved 7 June 2010.

- UGPulse Uganda

- "Hand of Cause Visits African Villages". Baháʼí News. No. 362. May 1961. pp. 6–9.

- compiled and (2001). Greg Watson (ed.). "transcript of talks given by Mr. Nakhjavani and his wife". Informal Talks by Notable Figures. Bahai-library.com. Retrieved 30 August 2009.

- Baháʼí International Community (March 2000). "Madame Rúhíyyih Rabbáni, leading Baháʼí dignitary, passes away in Haifa". One Country. 11 (4). Retrieved 30 August 2009.

- Nakhjavani, Violette (2002). The Great African Safari – The travels of RúhíyyihKhánum in Africa, 1969–73. George Ronald Publisher Ltd. pp. 27–32. ISBN 978-0-85398-456-6.

- Smith, Peter; Momen, Moojan (1989). "The Baha'i Faith 1957–1988: A Survey of Contemporary Developments". Religion. 19 (1): 63–91. doi:10.1016/0048-721X(89)90077-8 – via Baháʼí Library Online.

- compiled by Wagner, Ralph D. "NIGER". Synopsis of References to the Baháʼí Faith, in the US State Department's Reports on Human Rights 1991–2000. Baháʼí Library Online. Retrieved 4 May 2008.

- Egyptian Initiative for Personal Rights (16 December 2006). "Government Must Find Solution for Baha'i Egyptians". eipr.org. Archived from the original on 9 February 2007. Retrieved 16 December 2006.

- Gonn, Adam (24 February 2009). "Victory in Court For Egyptian Baha'i". Cairo, Egypt: AHN. Archived from the original on 13 August 2011. Retrieved 24 May 2009.

- Reuters (3 April 2009). "Bahaʼi Homes Attacked in Egypt Village". Egypt: Javno.com. Archived from the original on 2 October 2009. Retrieved 25 May 2009.

- "Regional Conferences of the Five Year Plan; November 2008 – March 2009". Baháʼí International Community. 2009. Retrieved 21 March 2012.

- Baha'i Faith in India Archived 14 July 2014 at the Wayback Machine, FAQs, National Spiritual Assembly of the Baháʼís of India

- The Baha'i Faith in India

- "C-01 Appendix : Details of Religious Community Shown Under 'Other Religions And Persuasions' In Main Table C-1- 2011 (India & States/UTs)". Office of the Registrar General & Census Commissioner, India. Retrieved 23 October 2020.

- "Baha'i Faith History in Azerbaijan". National Spiritual Assembly of the Baháʼís of Azerbaijan. Archived from the original on 19 February 2012. Retrieved 22 December 2008.

- Momen, Moojan. "Russia". Draft for "A Short Encyclopedia of the Baháʼí Faith". Baháʼí Library Online. Retrieved 14 April 2008 – via Baháʼí Library Online.

- Local Spiritual Assembly of Kyiv (August 2007). "Statement on the history of the Baháʼí Faith in Soviet Union". Official Website of the Baháʼís of Kyiv. Local Spiritual Assembly of Kyiv. Archived from the original on 15 July 2010. Retrieved 19 April 2008.

- "Notes on the Bábí and Baháʼí Religions in Russia and its Territories", by Graham Hassall, Journal of Baháʼí Studies, 5.3 ( September–December 1993)

- Effendi, Shoghi (11 March 1936). The World Order of Baháʼu'lláh (1991 first pocket-size ed.). Haifa, Palestine: US Baháʼí Publishing Trust. pp. 64–67.

- Momen, Moojan (1994). "Turkmenistan". draft of "A Short Encyclopedia of the Baha'i Faith". Baháʼí Library Online. Archived from the original on 10 February 2012. Retrieved 21 May 2008.

- Hassall, Graham (2000). "Notes on Research on National Spiritual Assemblies". Asia Pacific Baháʼí Studies. Retrieved 12 June 2015 – via Baháʼí Library Online.

- ʻAbbas, ʻAbdu'l-Bahá (April 1919). Tablets, Instructions and Words of Explanation. Mirza Ahmad Sohrab (trans. and comments) – via Baháʼí Library Online.

- ʻAbdu'l-Bahá (1991) [1916–17]. Tablets of the Divine Plan (Paperback ed.). Wilmette, Illinois, USA: Baháʼí Publishing Trust. pp. 31–36. ISBN 978-0-87743-233-3.

- Universal House of Justice (1986). In Memoriam. The Baháʼí World. XVIII. Baháʼí World Centre. pp. 733–736. ISBN 978-0-85398-234-0 – via Baháʼí Library Online.

- Lamb, Artemus (November 1995). The Beginnings of the Baháʼí Faith in Latin America:Some Remembrances, English Revised and Amplified Edition. West Linn, Oregon: M L VanOrman Enterprises – via Baháʼí Library Online.

- Effendi, Shoghi (1947). Messages to America. Wilmette, Illinois, USA: Baháʼí Publishing Committee. p. 6. ISBN 978-0-87743-145-9. OCLC 5806374.

- Universal House of Justice (1966). "Ridván 1966". Ridván Messages. Baháʼí Library Online. Retrieved 4 December 2008.

- "The Great Safari of Hand of the Cause Ruhiyyih Khanum; Barbados". Baháʼí News. No. 483. June 1971. pp. 17–18.

- "Most Baha'i Nations (2005)". QuickLists > Compare Nations > Religions >. The Association of Religion Data Archives. 2005. Retrieved 16 September 2012.

- Bausani, Alessandro and Dennis MacEoin (1989). "ʻAbd-al-Bahāʼ". Encyclopædia Iranica.

- Balyuzi 2001, pp. 159–397

- various (20 August 1911). Windust, Albert R.; Buikema, Gertrude (eds.). "various". Star of the West. 02 (9): all. Archived from the original on 7 November 2011. Retrieved 15 April 2010.

- ʻAbdu'l-Bahá; Wellesley Tudor Pole (1911). "The Bahai Movement". In Spiller, G. (ed.). Papers on Inter-racial Problems Communicated to the First Universal Races Congress. London: in London, P.S. King & Son and Boston, The World's Peace Foundation. pp. 154–157. Retrieved 25 April 2010.

- "Hippolyte Dreyfus, apôtre d'ʻAbdu'l-Bahá; Premier Baháʼí français". Qui est ʻAbdu'l-Bahá ?. Assemblée Spirituelle Nationale des Baháʼís de France. 9 July 2000. Retrieved 14 March 2010.

- ʻAbdu'l-Bahá (1 October 2006). "ʻAbdu'l-Bahá in London". National Spiritual Assembly of Britain. Retrieved 1 October 2006 – via Baháʼí Library Online.

- Lady Blomfield (1 October 2006). "The Chosen Highway". Wilmette, Illinois: US Baha'i Publishing Trust. Retrieved 8 November 2008 – via Baháʼí Library Online.

- Balyuzi 2001, p. 343

- Warburg, Margit (2004). Peter Smith (ed.). Baháʼís in the West. Kalimat Press. pp. 228–63. ISBN 978-1-890688-11-0.

- R. Rabbani, ed. (1992). The Ministry of the Custodians 1957–1963. Baháʼí World Centre. pp. 85, 124, 148–151, 306–9, 403, 413. ISBN 978-0-85398-350-7 – via Baháʼí Library Online.

- Walbridge, John (March 2002). "Chapter Four–The Baha'i Faith in Turkey". Occasional Papers in Shaykhi, Babi and Baha'i Studies. 06 (1).

- Universal House of Justice (1986). In Memoriam. The Baháʼí World. XVIII. Baháʼí World Centre. pp. 797–800. ISBN 978-0-85398-234-0 – via Baháʼí Library Online.

- Kolarz, Walter (1962). Religion in the Soviet Union. Armenian Research Center collection. St. Martin's Press. pp. 470–473 – via Questia (subscription required) .

- Francis, N. Richard. "Excerpts from the lives of early and contemporary believers on teaching the Baháʼí Faith: Enoch Olinga, Hand of the Cause of God, Father of Victories". Archived from the original on 28 February 2008. Retrieved 18 February 2008.

- Smith, Peter (2000). "conferences and congresses, international". A concise encyclopedia of the Baháʼí Faith. Oxford: Oneworld Publications. pp. 109–110. ISBN 978-1-85168-184-6.

- "Statement on the history of the Baháʼí Faith in Soviet Union". Official Website of the Baháʼís of Kyiv. Local Spiritual Assembly of Kyiv. August 2007. Archived from the original on 15 July 2010. Retrieved 18 February 2010.

- High-ranking member of the Baha'i Faith passes away 26 November 2003

- Dunlop, John B. (1998). "Russia's 1997 Law Renews Religious Persecution" (PDF). Demokratizatsiya. Retrieved 21 September 2012.

- Stockman, Robert H. (2001). "The Search Ends". Thornton Chase: First American Baháʼí. Wilmette, Illinois: US Baha'i Publishing Trust. ISBN 978-0877432821 – via Baháʼí Library Online.

- ʻAbdu'l-Bahá (1991) [1916–17]. Tablets of the Divine Plan (Paperback ed.). Wilmette, Illinois, USA: Baháʼí Publishing Trust. pp. 31–32. ISBN 978-0-87743-233-3.

- ʻAbdu'l-Bahá (1991) [1916–17]. Tablets of the Divine Plan (Paperback ed.). Wilmette, IL: Baháʼí Publishing Trust. p. 104. ISBN 978-0877432333.

- "News of the Cause". Baháʼí News. No. 99. April 1936. p. 4.

- Effendi, Shoghi (1947). Messages to America. Wilmette, Illinois, USA: Baháʼí Publishing Committee. p. 6. ISBN 978-0877431459. OCLC 5806374.

- "U.S. Baha'i History". Baha'i Faith. Archived from the original on 19 September 2009. Retrieved 24 February 2009.

- The Baháʼí Faith: 1844–1963: Information Statistical and Comparative, Including the Achievements of the Ten Year International Baháʼí Teaching & Consolidation Plan 1953–1963. Haifa, Israel: Hands of the Cause Residing in the Holy Land. 1963. pp. 22, 46 – via Baháʼí Library Online.

- ʻAbdu'l-Bahá (1991) [1916–17]. Tablets of the Divine Plan (Paperback ed.). Wilmette, Illinois, USA: Baháʼí Publishing Trust. pp. 40/42. ISBN 978-0-87743-233-3.

- "Australian Baháʼí History". Official website of the Baháʼís of Australia. National Spiritual Assembly of the Baháʼís of Australia. Archived from the original on 19 July 2008. Retrieved 20 July 2008.

- William Miller (b. Glasgow 1875) and Annie Miller (b. Aberdeen 1877) – The First Believers in Western Australia Archived 26 February 2008 at the Wayback Machine The Scottish Baháʼí No.33 – Autumn, 2003

- Hassall, Graham (December 1998). "Seventy Five Years of the Baháʼí Faith in Victoria". presented at a dinner marking 75 years of the Baháʼí Faith in Victoria. Association for Baháʼí Studies, Australia – via Baháʼí Library Online.

- The Baháʼí Faith: 1844–1963: Information Statistical and Comparative, Including the Achievements of the Ten Year International Baháʼí Teaching & Consolidation Plan 1953–1963, Compiled by Hands of the Cause Residing in the Holy Land, pages 22 and 46.

- "Social and Economic Development and the Environment". International Conference "Indigenous Knowledge and Bioprospecting". Australian Association for Baha'i Studies. 28 April 2004. Archived from the original on 13 September 2007. Retrieved 20 July 2008.

- "Submission in response to selected questions from the Human Rights and Equal Opportunity Commission discussion paper, Striking the Balance: Women, men, work and family". Striking the Balance – Women, men, work and family. Australian Baháʼí Community. June 2005. Archived from the original on 23 September 2008. Retrieved 24 February 2009.

- Effendi, Shoghi (1997). "Introduction". Messages to the Antipodes:Communications from Shoghi Effendi to the Baháʼí Communities of Australasia. Peter Khan (Introduction). Mona Vale: Baháʼí Publications Australia. pp. and page 14. ISBN 978-0-909991-98-2 – via Baháʼí Library Online.

- Bain, Wilhemenia Sherriff (8 December 1908). "Behaïsm". Otago Witness. New Zealand. p. 87. Retrieved 10 September 2010.

- Elsmore, Bronwyn (22 June 2007). "Stevenson, Margaret Beveridge 1865– 1941 Baha'i". Dictionary of New Zealand Biography. Online. New Zealand Ministry for Culture and Heritage. Retrieved 19 September 2009.

- ʻAbdu'l-Bahá (1991) [1916-17]. Tablets of the Divine Plan (Paperback ed.). Wilmette, IL: Baháʼí Publishing Trust. pp. 47–59. ISBN 978-0-87743-233-3.

- Hassall, Graham (January 2000). "Clara and Hyde Dunn". draft of Short Encyclopedia of the Baháʼí Faith. bahai-library.com. Retrieved 28 September 2009.

- Effendi, Shoghi; J. E. Esslemont (1982). Arohanui: Letters from Shoghi Effendi to New Zealand. Suva, Fiji Islands: Baháʼí Publishing Trust of Suva, Fiji Islands. pp. Appendix, ??.

- "New Zealand community —Historical timeline". New Zealand Community. National Spiritual Assembly of the Baháʼís of New Zealand. Archived from the original on 23 October 2007. Retrieved 19 September 2009.

- ʻAbdu'l–Bahá (1991) [1916–17]. Tablets of the Divine Plan (Paperback ed.). Wilmette, Illinois, USA: Baháʼí Publishing Trust. p. 40. ISBN 978-0-87743-233-3.

- Hassall, Graham (9 March 1994). "Clara and Hyde Dunn". draft of "A Short Encyclopedia of the Baha'i Faith". Baháʼí Library Online. Retrieved 15 June 2008.

- National Spiritual Assembly of the Baháʼís of Samoa (February 2004). "50th Anniversary of the Baháʼí Faith in Samoa". Waves of One Ocean, Official Baháʼí website. National Spiritual Assembly of the Baháʼís of Samoa. Archived from the original on 4 September 2009. Retrieved 15 June 2008.

- International Community, Baháʼí (30 November 2004). "Timeline of significant evens in the history of the Baháʼí Faith in Samoa and American Samoa (1954 –2004.)". Baháʼí World News Service.

- International Community, Baháʼí (September 2006). Century of Light. Project Gutenberg: Baháʼí International Community. p. 122.

- "Samoa Facts and Figures from Encarta – People". Encarta. Online. Microsoft. 2008. Archived from the original on 13 September 2009. Retrieved 15 June 2008.

Further reading

- Stockman, Robert; Winters, Jonah (1997). "Baháʼí Communities of the World". Resource Guide for the Scholarly Study of the Baháʼí Faith (Online ed.). Research Office of the Baháʼí National Center – via Baháʼí Library Online.

- Academic American Encyclopedia. Grolier Academic Reference. 1998. ISBN 978-0-7172-2068-7.

- Bowker, John W., ed. (1997). The Oxford Dictionary of World Religions. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-213965-8.

- Chernow, Barbara A.; Vallasi, George A. (1993). The Columbia Encyclopedia. Houghton Mifflin. ISBN 978-0-395-62438-8.

- The Encyclopedia of Islam, New Edition. Brill. 1960. Ref DS37.E523.

- Hinnells, John R. (2000). The New Penguin Handbook of Living Religions (second ed.). Penguin. ISBN 978-0-14-051480-3.

- Jones, Lindsay, ed. (2005). Encyclopedia of Religion (second ed.). MacMillan Reference Books. ISBN 978-0-02-865733-2.

- Mattar, Philip, ed. (2004). Encyclopedia of Modern Middle East & North Africa. Thomson/Gale. ISBN 978-0-02-865769-1.

- O'Brien, Joanne; Palmer, Martin (2005). Religions of the World. Facts on File. ISBN 978-0-8160-6258-4.

- Oliver, Paul (2002). Teach Yourself World Faiths. McGraw-Hill. ISBN 978-0-07-138448-3.

- Roof, Wade C. (1993). A Generation of Seekers: Spiritual Journeys of the Baby Boom Generation. HarperCollins. ISBN 978-0-06-066964-5.

- Sanasarian, Eliz (2000). Religious Minorities in Iran. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-77073-6.

- Sims, Barbara (1989). Traces That Remain: A Pictorial History of the Early Days of the Baháʼí Faith Among the Japanese. Osaka, Japan: Japan Baháʼí Publishing Trust – via Baháʼí Library Online.

- Smith, Jonathan Z.; American Academy of Religion (1995). The Harpercollins Dictionary of Religion. HarperCollins. ISBN 978-0-06-067515-8.

- World Book editors (2002). The World Book Encyclopedia. World Book Inc. ISBN 978-0-7166-0103-6.

External links

- Baháʼí World Statistics

- adherents.com – Specific compiled stats on Baháʼí communities