Bhadrabahu

Ācārya Bhadrabāhu (c. 367 - c. 298 BCE) was, according to the Digambara sect of Jainism, the last Shruta Kevalin (all knowing by hearsay, that is indirectly) in Jainism but Śvētāmbara, believes the last Shruta Kevalin was Acharya Sthulabhadra, but was forbade by Bhadrabahu from disclosing it.[1][2] He was the last acharya of the undivided Jain sangha. He was the spiritual teacher of Chandragupta Maurya, the founder of Maurya Empire.[3]

Aacharya Bhadrabahu Swami | |

|---|---|

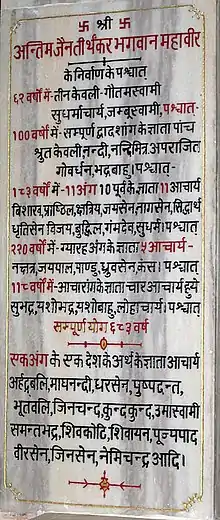

Late inscription at Shravanabelagola describing the incoming of Bhadrabahu and Chandragupta Maurya | |

| Personal | |

| Born | c. 367 BCE |

| Died | c. 298 BCE |

| Religion | Jainism |

| Sect | Digambara and Svetambara |

| Notable work(s) | Uvasagharam Stotra |

| Religious career | |

| Successor | Acharya Vishakha |

| Ascetics initiated | Chandragupta Maurya |

| Initiation | by Govarddhana Mahamuni |

| Part of a series on |

| Jainism |

|---|

|

|

|

According to the Digambara sect of Jainism, there were five Shruta Kevalins in Jainism - Govarddhana Mahamuni, Vishnu, Nandimitra, Aparajita and Bhadrabahu.[4]

Early life

Bhadrabahu was born in Pundravardhana (The region mainly consisted of parts of the Northern West Bengal and North-Western Bangladesh, i.e., parts of North Bengal[5]) to a Brahmin family[6] during which time the secondary capital of the Mauryas was Ujjain. When he was seven, Govarddhana Mahamuni predicted that he will be the last Shruta Kevali and took him along for his initial education.[4] According to Śvētāmbara tradition, he lived from 433 BCE to 357 BCE.[7] Digambara tradition dates him to have died in 365 BC.[8] Natubhai Shah dated him from 322 to 243 BCE.[9]

Yasobhadra (351-235 BCE), leader of the religious order reorganised by Mahavira, had two principle disciples, Sambhutavijaya (347-257 BCE) and Bhadrabahu.[9] After his death the religious order was divided in two lineages lead by Sambhutivijaya and Bhadrabahu.[9]

Ascetic life & Explanation of Sixteen Dreams of Chandragupta

On the night of full moon in the month of Kartik, Chandragupta Maurya (founder and ruler of Maurya Empire) saw sixteen dreams, which were then explained to him by Acharya Bhadrabahu.[10]

| S. No. | Dream of Chandragupta | Explanation by Bhadrabahu |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | The sun setting | All the knowledge will be darkened |

| 2 | A branch of the Kalpavriksha break off and fall | Decline of Jainism and Chandragupta's successors won't be initiated |

| 3 | A divine car descending in the sky and returning | The heavenly beings will not visit Bharata Kshetra |

| 4 | The disk of the moon sundered | Jainism will be split into two sects |

| 5 | Black elephants fighting | Lesser rains and poorer crops |

| 6 | Fireflies shining in the twilight | True knowledge will be lost, few sparks will glimmer with feeble light |

| 7 | A dried up lake | Aryakhanda will be destitute of Jain doctrines and falsehood will increase |

| 8 | Smoke filling all the air | Evil will start to prevail and goodness will be hidden |

| 9 | An ape sitting on a throne | Vile, low-born, wicked will acquire power |

| 10 | A dog eating the payasa out of a golden bowl | Kings, not content with a sixth share, will introduce land-rent and oppress their subjects by increasing it |

| 11 | Young bulls labouring | Young will form religious purposes, but forsake them when old |

| 12 | Kshatriya boys riding donkeys | Kings of high descent will associate with the base |

| 13 | Monkeys scaring away swans | The low will torment the noble and try to reduce them to same level |

| 14 | Calves jumping over the sea | King will assist in oppressing the people by levying unlawful taxes |

| 15 | Foxes pursuing old oxen | The low, with hollow compliments, will get rid of the noble, the good and the wise |

| 16 | A twelve-headed serpent approaching | Twelve year of death and famine will come upon this land[11] |

Bhadrabahu was in Nepal for a 12-year penitential vow when the Pataliputra conference took place in 300 BCE to put together the Jain canon anew. Bhadrabahu decided the famine would make it harder for monks to survive and migrated with a group of twelve thousand disciples to South India,[12][13] bringing with him Chandragupta, turned Swetambar monk.[14][11]

According to the inscriptions at Shravanabelgola, Bhadrabahu died after taking the vow of kevalgyan.[15]

Works

According to Svetambaras, Bhadrabahu was the author of Kalpa Sūtra,[16] four Chedda sutras, commentaries on ten scriptures, Bhadrabahu Samhita and Vasudevcharita.[17][6]

Legacy

Bhadrabahu was the last acharya of the undivided Jain sangha. After him, the Sangha split into two separate teacher-student lineages of monks. Digambara monks belong to the lineage of Acharya Vishakha and Svetambara monks follow the tradition of Acharya Sthulabhadra.[18]

Regarding the inscriptions describing the relation of Bhadrabahu and Chandragupta Maurya, Radha Kumud Mookerji writes,

The oldest inscription of about 600 AD associated "the pair (yugma), Bhadrabahu along with Chandragupta Muni." Two inscriptions of about 900 AD on the Kaveri near Seringapatam describe the summit of a hill called Chandragiri as marked by the footprints of Bhadrabahu and Chandragupta munipati. A Shravanabelagola inscription of 1129 mentions Bhadrabahu "Shrutakevali", and Chandragupta who acquired such merit that he was worshipped by the forest deities. Another inscription of 1163 similarly couples and describes them. A third inscription of the year 1432 speaks of Yatindra Bhadrabahu, and his disciple Chandragupta, the fame of whose penance spread into other words.[14]

Bhadrabahu-charitra was written by Ratnanandi of about 1450 CE.[14]

Notes

- Fynes, F.C.C. (1998). Hemachandra The Lives of Jain Elders (1998 ed.). Oxford: Oxford University Press, Oxford World Classics. p. xxi. ISBN 0-19-283227-1.

- Bhattacharyya, N.N. (2009). Jainism, a Concise Encyclopedia. New Delhi: Manohar Publishers and Distributors. p. 235. ISBN 81-7304-312-4.

- Wiley 2009, p. 51.

- Rice 1889, p. 3.

- Majumdar, R.C. (1971). History of Ancient Bengal (1971 ed.). Calcutta: G.Bharadwaj & Co. p. 12 & 13.

- Jaini, Padmanabh (2000). Collected Papers on Jaina Studies. Motilal Banarasidass. p. 299.

- Vidyabhusana 2006, p. 164.

- Vidyabhusana 2006, p. 164-165.

- Natubhai Shah 2004, p. 42.

- Rice 1889, p. 4.

- Sangave 2001, p. 174.

- Dundas 2002, p. 47.

- Rice 1889, p. 5.

- Mookerji 1988, p. 40.

- Sangave 1981, p. 32.

- Mookerji 1988, p. 4.

- Wiley 2009, p. 52.

- Natubhai Shah 2004, p. 39.

Sources

- Dundas, Paul (2002) [1992], The Jains (Second ed.), Routledge, ISBN 0-415-26605-X

- Mookerji, Radha Kumud (1988) [first published in 1966], Chandragupta Maurya and his times (4th ed.), Motilal Banarsidass, ISBN 81-208-0433-3

- Sangave, Vilas Adinath (1981), The Sacred Sravana-Belagola: A Socio-religious study (First ed.), Bharatiya Jnanpith

- Sangave, Vilas Adinath (2001), Facets of Jainology: Selected Research Papers on Jain Society, Religion, and Culture, Popular Prakashan, ISBN 978-81-7154-839-2

- Shah, Natubhai (2004) [First published in 1998], Jainism: The World of Conquerors, I, Motilal Banarsidass, ISBN 978-81-208-1938-2

- Wiley, Kristi L (16 July 2009), The a to Z of Jainism, p. 51, ISBN 9780810868212

- Vidyabhusana, Satis Chandra (2006) [1920], A History of Indian Logic: Ancient, Mediaeval and Modern Schools, Motilal Banarsidass, ISBN 81-208-0565-8

External links

Media related to Bhadrabahu at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Bhadrabahu at Wikimedia Commons