Black people and Mormonism

Over the past two centuries, the relationship between black people and Mormonism includes both official and unofficial discrimination. From the mid-1800s until 1978, the LDS Church prevented most men of black African descent from being ordained to the church's lay priesthood, barred black men and women from participating in the ordinances of its temples and opposed interracial marriage. Since black men of African descent could not receive the priesthood, they were excluded from holding leadership roles and performing these rituals. Temple ordinances such as the endowment and marriage sealings are necessary for the highest level of salvation. The church's first presidents, Joseph Smith and Brigham Young, reasoned that black skin was the result of the Curse of Cain or the Curse of Ham. As early as 1844, leaders suggested that black people were less valiant in the pre-existence. Many leaders, including Ezra Taft Benson, were vocally opposed to the civil rights movement. Before the civil rights movement, the LDS Church's stance went largely unnoticed and unchallenged for around a century.

The LDS Church's stance towards slavery alternated several times in its history, from one of neutrality, to anti-slavery, to pro-slavery. Smith at times advocated both for and against slavery, eventually coming to take an anti-slavery stance later in his life. Young was instrumental in officially legalizing slavery in the Utah Territory, teaching that the doctrine of slavery was connected to the Curse of Cain. Twenty-nine African slaves were reported in the 1860 census. Slavery in Utah ended in 1862 when Congress abolished it.

In recent decades, The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints (LDS Church) has condemned racism and increased its proselytization efforts and outreach in black communities, but it still faces accusations of perpetuating implicit racism by not acknowledging, apologizing or adequately paying for its prior discriminatory practices and beliefs. In 1978, the First Presidency and the Quorum of the Twelve, led by church president Spencer W. Kimball, declared they had received a revelation that the time had come to end these restrictions. Kimball publicly refuted earlier justifications for the restrictions. A recent survey of self-identified Mormons revealed that over 60% of respondents either "know" or "believe" that the priesthood/temple ban was God's will.

Under church president Russell M. Nelson, the church began initiatives in 2019 to cooperate with the NAACP, leading to Nelson speaking at the NAACP national convention in 2019 and issuing joint statements with the national leaders of the NAACP in 2020. A spokesperson for the NAACP in June 2020 criticized the LDS Church for not taking more action. In the church's October 2020 general conference, multiple leaders spoke against racism.

As of 2020, there were 3 operating temples in Africa, outside of South Africa, with 8 more in some stage of development or construction. There were also temples in the Dominican Republic, Haiti and several more in the African diaspora. In 2008, there were about 1 million black church members worldwide. The priesthoods of most other Mormon denominations, such as the Community of Christ, Bickertonite, and Strangite, have always been open to persons of all races.

Temple and priesthood restriction

From 1849 to 1978, the LDS Church prohibited anyone with real or suspected black ancestry from taking part in ordinances in its temples, serving in any significant church callings, serving missions,[1][2] attending priesthood meetings, being ordained to any priesthood office, speaking at firesides,[3][4]:67 or receiving a lineage in their patriarchal blessing.[5] In 1978, the church's First Presidency declared in a statement known as "Official Declaration 2" that the temple and priesthood ban had been lifted by the Lord. Before 1849, a few black men had been ordained to the priesthood under Joseph Smith. Non-black spouses of black people were also prohibited from entering the temple.[6] Over time, the ban was relaxed so that black people could attend priesthood meetings and people with a "questionable lineage" were given the priesthood, such as Fijians, Indigenous Australians, Egyptians, as well as Brazilians and South Africans with an unknown heritage who did not appear to have any black heritage.[7]:94

During this time, the church taught that the ban came from God and officially gave several race-based explanations for the ban, including a curse on Cain and his descendants,[8] Ham's marriage to Egyptus,[4] a curse on the descendants of Canaan,[9] and that black people were less valiant in their pre-mortal life.[10]:236 They used LDS scriptures to justify their explanations, including the Book of Abraham which teaches that the descendants of Canaan were black and Pharaoh could not have the priesthood because he was a descendant of Canaan.[8]:41–42 In 1978, the church issued a declaration that the Lord had revealed that the day had come in which all worthy males could receive the priesthood. This was later adopted as scripture.[11] They also taught that the ancient curse was lifted and that the Quorum of the Twelve heard the voice of the Lord.[4]:117 Today, none of these explanations are accepted as official doctrine, and the church has taken an anti-racism stance.[12]

History

During the early years of the Latter Day Saint movement, at least two black men held the priesthood and became priests: Elijah Abel and Walker Lewis.[15] Elijah Abel received both the priesthood office of elder and the office of seventy, evidently in the presence of Joseph Smith himself.[15] Later, the person who ordained Abel, Zebedee Coltrin stated that in 1834, Joseph Smith had told Coltrin that "the Spirit of the Lord saith the Negro had no right nor cannot hold the Priesthood," and that Abel should be dropped from the Seventies because of his lineage; while in 1908, President Joseph F. Smith, Joseph Smith's nephew, said that Abel's ordination had been declared null and void by his uncle personally, though, prior to this statement, he had previously denied any connection between the priesthood ban and Joseph Smith.[16][8] Historians Armand Mauss and Lester Bush, however, found that all references to Joseph Smith supporting a priesthood ban on blacks were made long after his death and seem to be the result of an attempted reconciliation of the contrasting beliefs and policies of Brigham Young and Joseph Smith by later church leaders.[8][17] No evidence from Smith's lifetime suggests that he ever prohibited blacks from receiving the priesthood.[8][17] Sources suggest that there were several other black priesthood holders in the early church, including Peter Kerr and Joseph T. Ball, a Jamaican immigrant.[18][19] Other prominent black members of the early church included Jane Manning James, Green Flake, and Samuel D. Chambers, among others.[20][21][22]

After Smith's death in 1844, Brigham Young became president of the main body of the church and led the Mormon pioneers to what would become the Utah Territory. Like many Americans at the time, Young, who was also the territorial governor, promoted discriminatory views about black people.[23] On January 16, 1852, Young made a pronouncement to the Utah Territorial Legislature, stating that "any man having one drop of the seed of [Cain] ... in him [could not] hold the priesthood."[8]:70 At the same time, however, Young also said that at some point in the future, black members of the church would "have [all] the privilege and more" that was enjoyed by other members of the church.[24] Some scholars have suggested that the actions of William McCary, a half-black man who also called himself a prophet and the successor to Joseph Smith, led to Young's decision to ban blacks from receiving the priesthood.[4] McCary went as far as once claiming to be Adam from the Bible, and was excommunicated from the church for apostasy.[8] As recorded in the Journal of Discourses, Young taught that black people's position as "servant of servants" was a law under heaven and it was not the church's place to change God's law.[25]:172[26]:290

Under the racial restrictions that lasted from Young's presidency until 1978, persons with any black African ancestry could not receive church priesthood or any temple ordinances including the endowment and eternal marriage or participate in any proxy ordinances for the dead. An important exception to this temple ban was that (except for a complete temple ban period from the mid-1960s until the early 70s under McKay)[27]:119 black members had been allowed a limited use recommend to act as proxies in baptisms for the dead.[7]:95[4]:164[28] The priesthood restriction was particularly limiting, because the LDS Church has a lay priesthood and most male members over the age of 12 have received the priesthood. Holders of the priesthood officiate at church meetings, perform blessings of healing, and manage church affairs. Excluding black people from the priesthood meant that men could not hold any significant church leadership roles or participate in many important events such as performing a baptism, blessing the sick, or giving a baby blessing.[4]:2 Between 1844 and 1977, most black people were not permitted to participate in ordinances performed in the LDS Church temples, such as the endowment ritual, celestial marriages, and family sealings. These ordinances are considered essential to enter the highest degree of heaven, so this meant that they could not enjoy the full privileges enjoyed by other Latter-day Saints during the restriction.[4]:164

Celestial marriage

For Latter-day Saints, a celestial marriage is not required to get into the celestial kingdom, but is required to obtain a fullness of glory or exaltation within the celestial kingdom.[29] The righteous who do not have a celestial marriage would still live eternally with God, but they would be "appointed angels in heaven, which angels are ministering servants."[30] As black people were banned from entering celestial marriage prior to 1978,[31] some interpreted this to mean that they would be treated as unmarried whites, being confined to only ever live in God's presence as a ministering servant. Apostles George F. Richards[32] and Mark E. Petersen[33] taught that blacks could not achieve exaltation because of their priesthood and temple restrictions. Several leaders, including Joseph Smith,[34] Brigham Young,[35] Wilford Woodruff,[36] George Albert Smith,[37] David O. McKay,[38] Joseph Fielding Smith,[39] and Harold B. Lee[40] taught that black people would eventually be able to receive a fullness of glory in the celestial kingdom. In 1973 church spokesperson Wendell Ashton stated that Mormon prophets have stated that the time will come when black Mormon men can receive the priesthood.[41]

Patriarchal blessing

In the LDS Church, a patriarch gives patriarchal blessings to members to help them know their strengths and weaknesses and what to expect in their future life. The blessings also tell members which tribe of Israel they are descended from. Members who are not literally descended from the tribes are adopted into a tribe, usually Ephraim. In the early 19th and 20th centuries, members were more likely to believe they were literally descended from a certain tribe.[42] The LDS Church keeps copies of all patriarchal blessings. In Elijah Abel's 1836 patriarchal blessing, no lineage was declared, and he was promised that in the afterlife he would be equal to his fellow members, and his "soul be white in eternity". Jane Manning James's blessing in 1844 gave the lineage of Ham.[43]:106 Later, it became church policy to declare no lineage for black members. In 1934, patriarch James H. Wallis wrote in his journal that he had always known that black people could not receive a patriarchal blessing because of the priesthood ban, but that they could receive a blessing without a lineage.[5] In Brazil, this was interpreted to mean that if a patriarch pronounced a lineage, then the member was not a descendant of Cain and was therefore eligible for the priesthood, despite physical or genealogical evidence of African ancestry.[44]

Actual patriarchs did not strictly adhere to Wallis's statement. In 1961, the Church Historian's Office reported that other lineages had been given, including from Cain. In 1971, the Presiding Patriarch stated that non-Israelite tribes should not be given as a lineage in a patriarchal blessing. In a 1980 address to students at Brigham Young University, James E. Faust attempted to assure listeners that if they had no declared lineage in their patriarchal blessing, that the Holy Ghost would "purge out the old blood, and make him actually of the seed of Abraham."[5] After the 1978 revelation, patriarchs sometimes declared lineage in patriarchal blessings for black members, but sometimes they did not declare a lineage. Some black members have asked for and received new patriarchal blessings including a lineage.[45]

Direct commandment of God (Doctrine) vs. Policy

Church leaders taught for decades that the priesthood ordination and temple ordinance ban was commanded by God. Brigham Young taught it was a "true eternal principle the Lord Almighty has ordained."[4]:37 In 1949, the First Presidency under George Albert Smith officially stated that it "remains as it has always stood" and was "not a matter of the declaration of a policy but of direct commandment from the Lord".[46]:222–223[47][8]:221 A second First Presidency statement (this time under McKay) in 1969 re-emphasized that this "seeming discrimination by the Church towards the Negro is not something which originated with man; but goes back into the beginning with God".[48][46]:223[8]:222 As president of the church, Kimball also emphasized in a 1973 press conference that the ban was "not my policy or the Church's policy. It is the policy of the Lord who has established it."[49] On the topic of doctrine and policy for the race ban lifting, the apostle Dallin H. Oaks stated in 1988, "I don't know that it's possible to distinguish between policy and doctrine in a church that believes in continuing revelation and sustains its leader as a prophet. ... I'm not sure I could justify the difference in doctrine and policy in the fact that before 1978 a person could not hold the priesthood and after 1978 they could hold the priesthood."[50] The research of historians Armand Mauss, Newell G. Bringhurst, and Lester E. Bush weakened the idea that the ban was doctrinal.[4] Bush noted that there was, in fact, no record of any revelation received by Brigham Young concerning the ban.[17] Justification for Young's policies were developed much later by scholars of the church, and Bush identified and commentated on the many ungrounded assumptions that led to such justification.[17] The church has since refuted earlier justification for the priesthood ban and no longer teaches it as doctrine.

End of the temple and priesthood bans

On June 8, 1978, the LDS Church's First Presidency released an official declaration which would allow "all worthy male members of the church [to] be ordained to the priesthood without regard to race or color",[11] and which allowed black men and women access to endowments and sealings in the temple.[51][52] According to the accounts of several of those present, while praying in the Salt Lake Temple, the First Presidency and the Quorum of the Twelve Apostles received the revelation relating to the lifting of the temple and priesthood ban. The apostle McConkie wrote that all present "received the same message" and were then able to understand "the will of the Lord."[53][4]:116 There were many factors that led up to the publication of this declaration: trouble from the NAACP because of priesthood inequality,[54] the announcement of the first LDS temple in Brazil,[55] and other pressures from members and leaders of the church.[56]:94–95 After the publication of Lester Bush's seminal article in Dialogue, "Mormonism's Negro Doctrine: An Historical Overview", BYU vice-president Robert K. Thomas feared that the church would lose its tax exemption status. The article described the church's racially discriminatory practices in detail. The article inspired internal discussion among church leaders, weakening the idea that the priesthood ban was doctrinal.[4]:95

Post 1978 theology regarding the restrictions

The 1978 lifting of the restrictions did not explain a reason for them, and neither did the announcement renounce, apologize or present new theological underpinnings for the restrictions.[57]:163 Because these ideas were not officially and explicitly repudiated the justifications, ideas, and beliefs that had sustained the restrictions for generations continue to persist.[57]:163,174[58]:84 Apostle Bruce R. McConkie continued to teach that Black people were descended from Cain and Ham until his death, that the curse came from God, but that it had been lifted by God in 1978.[59] His influential book Mormon Doctrine, published by LDS Church owned Deseret Book, perpetuated these racial teachings, going through 40 printings and selling hundreds of thousands of copies until it was pulled from shelves in 2010.[59][60]

In 2012, Randy L. Bott, a BYU professor, suggested that God denied the priesthood to black men in order to protect them from the lowest rung of hell, since one of few damnable sins is to abuse the exercise of the priesthood. Bott compared the priesthood ban to a parent denying young children the keys to the family car, stating: "You couldn't fall off the top of the ladder, because you weren't on the top of the ladder. So, in reality the blacks not having the priesthood was the greatest blessing God could give them."[61] The church responded to these comments by stating the views do not represent the church's doctrine or teachings, nor do BYU professors speak on its behalf.[62]

In a 2016 landmark survey,[63] almost two-thirds of 1,156 self-identified Latter-day Saints reported believing the pre-1978 temple and priesthood ban was "God's will".[64][65] Non-white members of the church were almost 10% more likely to believe that the ban was "God's will" than white members.[66]

Joseph Smith's beliefs in relation to Black people

Joseph Smith, founder of the Latter Day Saint movement, shifted his public attitude toward slavery several times, eventually coming to take an anti-slavery stance later in his life.[67]

Initially, Smith expressed opposition to slavery, but, after the church was formally organized in 1830, Smith and other authors of the church's official newspaper, The Evening and Morning Star, avoided any discussion of the controversial topic.[67][68] The major reason behind this decision was the mounting contention between the Mormon settlers, who were primarily abolitionists, and the non-Mormon Missourians, who usually supported slavery. Church leaders like Smith often attempted to avoid the topic and took a public position of neutrality during the Missouri years.[67]

On December 25, 1832, Smith authored the document, "Revelation and Prophecy on War."[67][69] In this text, Smith stated that "wars ... will shortly come to pass, beginning at the rebellion of South Carolina [and] ... poured out on all nations." He went on to say that "it shall come to pass, after many days, slaves shall rise up against their masters, who shall be marshaled and disciplined for war."[67][69] It was another two decades until the document was formally disclosed by the church to the general public.[67] The document would later be canonized by the church as Section 87 of the Doctrine and Covenants.[67]

During the Missouri years, Smith attempted to maintain peace with the members' pro-slavery neighbors.[67] In August 1835, the church issued an official statement, declaring that it was not "right to interfere with bond-servants, nor baptize them contrary to the will and wish of their masters" nor cause "them to be dissatisfied with their situations in this life."[67] After this time, the official policy of the church was not to baptize slaves without the consent of the slaveowner, but this was only loosely enforced and some slaves, such as 13-year-old Samuel D. Chambers, were baptized in secret.[22] In April 1836, Smith published an essay sympathetic to the pro-slavery cause, arguing against a possible "race war," providing cautious justification of slavery based on the biblical Curse of Ham, and stating that Northerners had no "more right to say that the South shall not hold slaves, than the South have to say that the North shall."[67]

Anti-Mormon sentiment among the non-Mormon Missourians continued to rise. A manifesto was published by many Missouri public officials, stating that "In a late number of the Star, published in Independence by the leaders of the sect, there is an article inviting free Negroes and mulattoes from other states to become 'Mormons,' and remove and settle among us."[70][71] The manifesto continued: "It manifests a desire on the part of their society, to inflict on our society an injury that they know would be to us entirely insupportable, and one of the surest means of driving us from the country; for it would require none of the supernatural gifts that they pretend to, to see that the introduction of such a caste among us would corrupt our blacks, and instigate them to bloodshed."[70][71] Eventually, the contention became too great and violence broke out between the Latter-day Saints and their neighbors in a conflict now referred to as the Missouri Mormon War. Governor Lilburn Boggs issued Executive Order 44, ordering the members of the church to leave Missouri or face death. The Latter Day Saints were forcibly removed and came to settle in Nauvoo, Illinois.

During the Nauvoo settlement, Smith began preaching abolitionism and the equality of the races. During his presidential campaign, Smith called for "the break down [of] slavery," writing that America must "Break off the shackles from the poor black man, and hire him to labor like other human beings."[72][68] He advocated that existing slaves be purchased from their masters using funds gained from the sale of public lands and the reduction of the salaries of federal congressmen, and called for the several million newly freed slaves to be transported to Texas.[68] Joseph Smith wished to free all slaves through this process by 1850.[68] Mormon historian Arnold K. Garr has noted that Smith's chief concern was not slavery but the exercise of executive power.[73] On February 7, 1844, Smith would write that "Our common country presents to all men the same advantages, the facilities, the same prospects, the same honors, and the same rewards; and without hypocrisy, the Constitution, when it says, 'We, the people of the United States, ... do ordain and establish this Constitution for the United States of America,' meant just what it said without reference to color or condition, ad infinitum."[72][74]

Smith was apparently present at the priesthood ordination of Elijah Abel, a man of partial African descent, to the offices of both elder and seventy, and allowed for the ordination of a couple of other black men into the priesthood of the early church.[75][76] Smith's successor, Brigham Young, would later adopt the policy of prohibiting black people from receiving the priesthood after Smith's death.[76] In 1841, Joseph Smith stated that if the opportunity to blacks were equal to the opportunity provided to whites, black people could perform as well or even outperform whites. While some religious leaders of the time presented arguments that blacks had no souls, Joseph Smith stated, in reference to black individuals, "They have souls, and are subjects of salvation. Go into Cincinnati or any city, and find an educated negro, who rides in his carriage, and you will see a man who has risen by the powers of his own mind to his exalted state of respectability."[77][68]

Smith argued that blacks and whites would be better off if they were "separate but legally equal," at times advocating for segregation and stating "Had I anything to do with the negro, I would confine them by strict law to their own species, and put them on a national equalization."[77][78]

Historian Fawn Brodie stated in her biography of Smith that he crystallized his hitherto vacillating views on black people with his authorship of The Book of Abraham, one of the LDS church's foundational texts, which justifies a priesthood ban on ancient Egyptians, who inherited the curse of the black skin on the basis of their descent from Noah's son Ham.[79] Brodie also wrote that Smith developed the theory that black skin was a sign of neutral behavior during a pre-existent war in heaven.[80] The official pronouncements of the church's First Presidency in 1949 and 1969 also attributed the origin of the priesthood ban to Joseph Smith, stating that the reason “antedates man's mortal existence.”[81] Several other scholars, such as Armand Mauss and Lester E. Bush, have since contested this theory, though, citing that a priesthood ban was never, in fact, implemented in Joseph Smith's time, and that Smith allowed for the ordination of several black men to the priesthood and even positions of authority within the church.[8]:221[17][80] Critics of Brodie's theory that the priesthood ban began with Joseph Smith generally agree that the ban actually originated as a series of racially-motivated administrative policies under Brigham Young, rather than revealed doctrine, which were inaccurately represented as revelation by later general authorities of the church.[82][8][17] There is no existing record of any revelation received by Young concerning the ban, weakening the idea that it was doctrinal.[8] The denial of the priesthood to blacks can easily be traced to Brigham Young, but there is no contemporary evidence that would suggest it originated with Joseph Smith.[17] Mauss and Bush found that all references to Joseph Smith supporting the doctrine were made long after his death and seem to be the result of an attempted reconciliation of the contrasting beliefs and policies of Brigham Young and Joseph Smith.[8][17] Young himself also never associated the priesthood ban with Joseph Smith's teachings, nor did most of the earliest general authorities.[8] Mauss and Bush detailed various problems with the theory that the Book of Abraham justified a priesthood restriction on blacks, pointing out that the effort to link Pharaoh and the Egyptian people with "black skin" and the antediluvian people of Canaan was "especially strained" and the lack of specificity in the account made such beliefs somewhat ungrounded.[8] Outside of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, most other Latter-day Saint churches remained open to the ordination of blacks into the priesthood.

Teachings about black people

Teachings about black people and the pre-existence

One of the justifications which the LDS Church used for its discriminatory policy was its belief that black individual's pre-existence spirits were not as virtuous as white pre-existence spirits. Brigham Young rejected the idea, but Orson Pratt supported it.[83] Formally, this justification appeared as early as 1908 in a Liahona magazine article.[4]:56 Joseph Fielding Smith supported the idea in his 1931 book The Way to Perfection, stating that the priesthood restriction on black was a "punishment" for actions in the pre-existence.[84] In a letter in 1947, the First Presidency wrote in a letter to Lowry Nelson that blacks were not entitled to the full blessings of the gospel, and referenced the "revelations [...] on the preexistence" as a justification.[85][86][16]:67 In 1952, Lowry published a critique of the racist policy in an article in The Nation.[87] Lowry believes it was the first time the folk doctrine that blacks were less righteous in the pre-existence was publicized to the non-Mormon world.[88]

The LDS Church also used this explanation in its 1949 statement which explicitly barred blacks from holding the priesthood.[4]:66 An address by Mark E. Peterson was widely circulated by BYU's religious faculty in the 1950s and 1960s and they used the "less valiant in the pre-existence" explanation to justify racial segregation, a view which Lowell Bennion and Kendall White, among other members, heavily criticized.[4]:69 The apostle Joseph Fielding Smith also taught that black people were less faithful in the preexistence.[89][90] A 1959 report by US Commission found that the LDS Church in Utah generally taught that non-whites had inferior performance in the pre-earth life.[91]

After the priesthood ban was lifted in 1978, church leaders refuted the belief that black people were less valiant in the pre-existence. In a 1978 interview with Time magazine, Spencer W. Kimball stated that the LDS Church no longer held to the theory that those of African descent were any less valiant in the pre-earth life.[4]:134

In a 2006 interview for the PBS documentary The Mormons, apostle Jeffrey R. Holland called the idea that blacks were less valiant in the pre-existence an inaccurate racial "folklore" invented in order to justify the priesthood ban, and the reasons for the previous ban are unknown.[4]:134[92][93]:60 The church explicitly denounced any justification of the priesthood restriction which was based on views of events which occurred in the pre-mortal life in the "Race and the Priesthood" essay which was published on its website in 2013.[31]

Curses of Cain and Ham

According to the Bible, after Cain killed Abel, God cursed him and put a mark on him, although the Bible does not state what the nature of the mark was.[94] The Pearl of Great Price, another Mormon book of scripture, describes the descendants of Cain as dark-skinned.[4]:12 In another biblical account, Ham discovered his father Noah drunk and naked in his tent. Because of this, Noah cursed Ham's son, Canaan to be "servants of servants".[95][46]:125 Although the scriptures do not mention Ham's skin color, a common Christian interpretation of these verses, which pre-dates Mormonism, associated the curse with black people and used it to justify slavery.[46]:125

Both Joseph Smith and Brigham Young referred to the curse as a justification for slavery at some point in their lives.[46]:126[96][97] Prior to the Latter Day Saint settlement in Missouri, Joseph Smith, like many other Northerners, was opposed to slavery, but softened his opposition to slavery during the Missouri years, going as far as writing a very cautious justification of the institution. Following the Mormon Extermination Order and violent expulsion of the church from the slave state, Joseph Smith openly embraced abolitionism and preached the equality of all of God's children, in 1841 stating that if opportunity for blacks were equal to the opportunity provided to whites, blacks could perform as well or even outperform whites. Brigham Young, however, while seemingly open to blacks holding the priesthood in his earlier years and praising of black members of the church, later used the curse as justification of barring blacks from the priesthood, banning interracial marriages, and opposing black suffrage.[8]:70[98][99][100] He stated that the curse would one day be lifted and that black people would be able to receive the priesthood post-mortally.[4]:66

Young once taught that the devil was black,[101] and his successor as church president, John Taylor, taught on multiple occasions that the reason that black people (those with the curse of Cain) were allowed to survive the flood was so that the devil could be properly represented on the earth through the children of Ham and his wife Egyptus.[46]:158[102][103] The next president, Wilford Woodruff also affirmed that millions of people have Cain's mark of blackness drawing a parallel to modern Native American's "curse of redness".[104] None of these ideas are accepted as official doctrine of the church.

In a 1908 Liahona article for missionaries, an anonymous but church-sanctioned author reviewed the scriptures about blackness in the Pearl of Great Price. The author postulated that Ham married a descendant of Cain. Therefore Canaan received two curses, one from Noah, and one from being a descendant of Cain.[4]:55 The article states that Canaan was the "sole ancestor of the Negro race" and explicitly linked his curse to be "servant of servants" to black priesthood denial.[4]:55 To support this idea, the article also discussed how Pharaoh, a descendant of Canaan according to LDS scripture, could not have the priesthood, because Noah "cursed him as pertaining to the Priesthood".[4]:58[105]

In 1931, apostle Joseph Fielding Smith wrote on the same topic in The Way to Perfection: Short Discourses on Gospel Themes, generating controversy within and without Mormonism. For evidence that modern blacks were descended from Cain, Smith wrote that "it is generally believed that" Cain's curse was continued through his descendants and through Ham's wife. Smith states that "some of the brethren who were associate with Joseph Smith have declared that he taught this doctrine." In 1978, when the church ended the ban on the priesthood, apostle Bruce R. McConkie taught that the ancient curse of Cain and Ham was no longer in effect.[4]:117

General authorities in the LDS Church favored Smith's explanation until 2013, when a Church-published online essay disavowed the idea that black skin is the sign of a curse.[4]:59[31] The Old Testament student manual, which is published by the church and is the manual currently used to teach the Old Testament in LDS institutes, teaches that Canaan could not hold the priesthood because of the cursing of Ham his father, but makes no reference to race.[106]

Antediluvian people of Canaan

According to the Book of Moses, the people of Canaan were a group of people that lived during the time of Enoch, before the Canaanites mentioned in the Bible. Enoch prophesied that the people of Canaan would war against the people of Shum, and that God would curse their land with heat, and that a blackness would come upon them. When Enoch called the people to repentance, he taught everyone except the people of Canaan. The Book of Abraham identifies Pharaoh as a Canaanite. There is no explicit connection from the antediluvian people of Canaan to Cain's descendants, the Canaanites descended from Ham's son Canaan or modern black people.[8]:41–42 However, the Book of Moses identifies both Cain's descendants and the people of Canaan as black and cursed, and they were frequently used interchangeably.[8][10] Bruce R. McConkie justified restrictions on teaching black people because Enoch did not teach the people of Canaan.[58]:1–12

Righteous black people would become white

Early church leaders believed that souls of everyone in the celestial kingdom (the highest degree of heaven) would be "white in eternity."[107][108] They often equated whiteness with righteousness, and taught that originally God made his children white in his own image.[10]:231[109][108] A 1959 report by the U.S. Commission on Civil Rights found that most Utah Mormons believed "by righteous living, the dark-skinned races may again become 'white and delightsome'."[91] Conversely, the church also taught that white apostates would have their skins darkened when they abandoned the faith.[110]

Several black Mormons were told that they would become white. Hyrum Smith told Jane Manning James that God could give her a new lineage, and in her patriarchal blessing promised her that she would become "white and delightsome".[43]:148 In 1808, Elijah Abel was promised that "thy soul be white in eternity".[111] Darius Gray, a prominent black Mormon, was told that his skin color would become lighter.[61] In 1978, apostle LeGrand Richards clarified that the curse of dark skin for wickedness and promise of white skin through righteousness only applied to Indians, and not to black people.[4]:115

In 2013, the LDS Church published an essay, refuting these ideas, describing prior reasoning for the restriction as racial "folk beliefs," and teaching that blackness in Latter-day Saint theology is a symbol of disobedience to God and not necessarily a skin color.[112]

Slavery

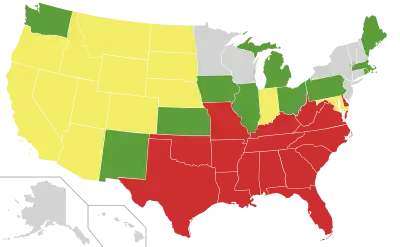

.jpg.webp)

Initial Mormon converts were from the north and opposed slavery. This caused contention in the slave state of Missouri, and the church leadership began distancing itself from abolitionism and sometimes justifying slavery based on the Bible. During this time, several slave owners joined the church and brought their slaves with them when they moved to Nauvoo. The church adopted scriptures which teach against influencing slaves to be "dissatisfied with their condition". Eventually, contention between the mostly-abolitionist Latter-day Saints and slave-owning Southerners led to the Mormon expulsion from Jackson County, Missouri in the Missouri Mormon War.

Joseph Smith began his presidential campaign on a platform for the government to buy slaves into freedom over several years. He called for "the break down of slavery" and the removal of "the shackles from the poor black man."[67] He was killed during his presidential campaign.

After the murder of Joseph Smith by a violent mob, fearful Latter-day Saints fled to Utah, then part of the Mexican province of Alta California, under the direction of Brigham Young. Some slave owners brought their slaves with them to Utah, though several slaves escaped. The church put out a statement of neutrality towards slavery, stating that it was between the slave owner and God. A few years later, Brigham Young began teaching that slavery was ordained of God, but remained opposed to creating a slave-based economy in Utah like that seen in the South.[113][114]

In 1852, the Utah Territory, under the governance of Brigham Young, legalized the slave trade for both Blacks and Native Americans. Under his direction, Utah passed laws supporting slavery and making it illegal for blacks to vote, hold public office, join the Nauvoo Legion, or marry whites.[115] Overall, "An Act in Relation to Service," the law that legalized slavery in the Utah Territory, contrasted with the existing statutes of the Southern states, in that it only allowed for a form of heavily-regulated slavery more similar to indentured servitude than to the mass plantation slavery of the South.[67] The law also contained passages that required slaveowners to prove that their slaves came to the territory "of their own free will and choice" and ensured that slaves could not be sold or moved without the consent of the slave themselves.[67] The Legislature demanded that slaves be declared free if there was any evidence they were abused by their masters.[116] Twenty-six African slaves were reported in the Utah Territory in the 1850 census, and twenty-nine were reported in the 1860 census.[117] Similar to the policies of other territories, one objective of the law was to prevent Black people from settling in Utah. Young told the legislature, "...the law of the last session so far proves a salutory measure, as it has nearly freed the territory, of the colored population; also enabling the people to control all who see proper to remain, and cast their lot among us."[118]

Many prominent members of the church owned or used slaves, including William H. Hooper, Abraham O. Smoot, Charles C. Rich, Brigham Young and Heber C. Kimball.[119][120]:52[4]:33 Members bought and sold slaves as property, gave the church slaves as tithing,[119][120]:34[121] and recaptured escaped slaves.[122][123]:268 In California, slavery was openly tolerated in the Mormon community of San Bernardino, despite being a free state. The US government freed the slaves and overturned laws prohibiting blacks from voting.[46]

Civil rights movement

After the Civil War, issues around black rights went largely unnoticed until the American civil rights movement. The National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP) criticized the church's position on civil rights, led anti-discrimination marches and filed a lawsuit against the church's practice of not allowing black children to be Boy Scout troop leaders.[54][124] Several athletes protested against BYU's discriminatory practices and the LDS Church's policy of not giving black men the priesthood.[125] In response, the Church issued a statement in support of civil rights and it also changed its policy on Boy Scouts. Apostle Ezra Taft Benson criticized the civil rights movement and challenged accusations of police brutality.[4]:78 African-American athletes at other schools protested against BYU's discriminatory practices by refusing to play against them.[125] After the reversal of the priesthood ban in 1978, the LDS church stayed relatively silent on matters of civil rights for a time, but eventually began meeting with and has formed a partnership with the NAACP.[126]

Beginning in 2017, local church leaders worked closely on projects with the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP) in Mississippi to restore the office where Medgar Evers had worked.[127] This cooperation received support from Jeffrey R. Holland of the Quorum of the Twelve Apostles. In 2018, it was announced that the Church and the NAACP would be starting a joint program that provided for the financial education of inner-city residents.[128] In 2019, Russel M. Nelson, president of the church, spoke at the national convention of the NAACP in Detroit.[129]

In June 2020, a spokesman for the NAACP said that there was "no willingness on the part of the church to do anything material. ... It's time now for more than sweet talk."[130]

In the October 2020 general conference of the church, multiple leaders spoke out against racism and called on church members to act against it. Church president Russell M. Nelson asked church members to "lead out in abandoning attitudes and actions of prejudice".[131][132][133] On October 27, 2020, in an address to the Brigham Young University student body, Dallin H. Oaks broadly denounced racism, endorsed the message of "black lives matter" while discouraging its use to advance controversial proposals, and called on students there and church members generally to work to root out racist attitudes, behaviors and policies.[134][135][136]

Segregation

During the first century of its existence, the church discouraged social interaction with blacks and encouraged racial segregation. Joseph Smith supported segregation, stating, "I would confine them [black people] by strict law to their own species".[137]:1843 Until 1963, many church leaders supported legalized racial segregation.[107] David O. McKay, J. Reuben Clark, Henry D. Moyle, Ezra Taft Benson, Joseph Fielding Smith, Harold B. Lee, and Mark E. Peterson were leading proponents of segregation.[4]:67 In the late 1940s First Presidency members publicly and privately condemned white-black marriage calling it "repugnant", "forbidden", and a "wicked virus".[138][139][140]

During the years, different black families were either told by church leadership not to attend church or chose not to attend church after white members complained.[141][142][143][4]:68 The church began considering segregated congregations,[141][144] and sent missionaries to southern United States to establish segregated congregations.[145][141]

In 1947, mission president, Rulon Howells, decided to segregate the branch in Piracicaba, Brazil, with white members meeting in the chapel and black members meeting in a member's home. When the black members resisted, arguing that integration would help everyone, Howells decided to remove the missionaries from the black members and stop visiting them.[44]:26 The First Presidency under Heber J. Grant sent a letter to stake president Ezra Taft Benson in Washington, D.C., advising that if two black Mormon women were "discreetly approached" they should be happy to sit at the back or side so as not to upset some white women who had complained about sitting near them in Relief Society.[16]:43 At least one black family was forbidden from attending church after white members complained about their attendance.[4]:68 In 1956, Mark E. Petersen suggested that a segregated chapel should be created for places where a number of black families joined.[144]

The church also advocated for segregation laws and enforced segregation in its facilities. Hotel Utah, a church-run hotel, banned black guests, even when other hotels made exceptions for black celebrities.[146] Blacks were prohibited from performing in the Salt Lake Tabernacle, and the Deseret News did not allow black people to appear in photographs with white people. Church leaders urged white members to join civic groups and opened up LDS chapels "for meetings to prevent Negroes from becoming neighbors", even after a 1948 Supreme Court decision against racial covenants in housing. They counseled members to buy homes so black people wouldn't move next to LDS chapels.[4]:67 In the 1950s, the San Francisco mission office took legal action to prevent black families from moving into the church neighborhood.[54] A black man living in Salt Lake City, Daily Oliver, described how, as a boy in the 1910s, he was excluded from an LDS-led boy scout troop because they did not want blacks in their building.[147][148] In 1954, apostle Mark E. Petersen taught that segregation was inspired by God, arguing that "what God hath separated, let not man bring together again".[7]:65 He used examples of the Lamanites and Nephites, the curse of Cain, Jacob and Esau, and the Israelites and Canaanites as scriptural precedence for segregation.[4]:69

Church leaders advocated for the segregation of donated blood, concerned that giving white members blood from black people might disqualify them from the priesthood.[4]:67 In 1943, the LDS Hospital opened a blood bank which kept separate blood stocks for whites and blacks. It was the second-largest in-hospital blood bank. After the 1978 ending of the priesthood ban, Consolidated Blood Services agreed to supply hospitals with connections to the LDS Church, including LDS Hospital, Primary Children's and Cottonwood Hospitals in Salt Lake City, McKay-Dee Hospital in Ogden, and Utah Valley Hospital in Provo. Racially segregated blood stocks reportedly ended in the 1970s, although white patients worried about receiving blood from a black donor were reassured that this would not happen even after 1978.[149]

Church leaders opposed desegregation in schools. After Dr. Robinson wrote an editorial in the Deseret News, President McKay deleted portions that indicated support for desegregation in schools, explaining it would not be fair to force a white child to learn with a black child.[7]:67 Decades earlier as a missionary he had written that he did "not care much for a negro".[7]:61 Apostle J. Rueben Clark instructed the Relief Society general president to keep the National Council of Women from supporting going on record in favor of school desegregation.[7]:63[150]:348

Brigham Young University and black students

Church leaders supported segregation at BYU. Apostle Harold B. Lee protested an African student who was given a scholarship, believing it was dangerous to integrate blacks on BYU's campus.[151]:852 In 1960 the NAACP reported that the predominantly LDS landlords of Provo, Utah would not rent to a BYU black student, and that no motel or hotel there would lodge hired black performers.[152]:206 Later that year BYU administrators hired a black man as a professor without the knowledge of its president Ernest Wilkinson. When Wilkinson found out he wrote that it was a "serious mistake of judgement", and "the danger in doing so is that students ... assume that there is nothing improper about mingling with other races", and the man was promptly reassigned to a departmental advisory position to minimize the risk of mingling.[152]:206–207

A few months later, BYU leaders were "very much concerned" when a male black student received a large number of votes for student vice president. Subsequently, Lee told Wilkinson he would hold him responsible if one of his granddaughters ever went to "BYU and bec[a]me engaged to a colored boy". Later the BYU Board of Trustees decided in February 1961 to officially encourage black students to attend other universities for the first time.[152]:207

In 1965, administrators began sending a rejection letter to black applicants which cited BYU's discouragement of interracial courtship and marriage as the motive behind the decision.[152]:210 By 1968, there was only one black American student on campus, though, Wilkinson wrote that year when responding to criticism that "all Negroes who apply for admission and can meet the academic standards are admitted."[152]:212–213 BYU's dean of athletics Milton Hartvigsen called the Western Athletic Conference's 1969 criticism of BYU's ban on black athletes bigotry towards a religious group, and the next month Wilkinson accused Stanford University of bigotry for refusing to schedule athletic events with BYU over its discrimination towards black athletes.[152]:219–220

In 1976, an African-American, Robert Lee Stevenson was elected a student body vice present at BYU.[153]

In 2002, BYU elected its first African-American student body president.[154][155]

In June 2020, BYU formed a committee on race and inequality.[156]

Interracial marriages and interracial sexual relations

The church's stance against interracial marriage held consistent for over a century while attitudes towards black people and the priesthood and equal rights saw considerable changes. Nearly every decade beginning with the church's formation until the '70s saw some denunciation against miscegenation. Church leaders' views stemmed from the priesthood policy and racist "biological and social" principles of the time.[8]:89–90[16]:42–43

19th century

One of the first times that anti-miscegenation feelings were mentioned by church leaders, occurred on February 6, 1835. An assistant president of the church, W. W. Phelps, wrote a letter theorizing that Ham's wife was a descendant of Cain and that Ham himself was cursed for "marrying a black wife".[158][46][8]:59[159] Joseph Smith wrote that he felt that black peoples should be "confined by strict law to their own species," which some have said directly opposes Smith's advocacy for all other civil rights.[4]:98 In Nauvoo, it was against the law for black men to marry whites, and Joseph Smith fined two black men for violating his prohibition of intermarriage between blacks and whites.[160]

In 1852, the Utah legislature passed Act in Relation to Service which carried penalties for whites who had sexual relations with blacks. The day after it passed, church president Brigham Young explained that if someone mixes their seed with the seed of Cain, that both they and their children will have the Curse of Cain. He then prophesied that if the Church were approve of intermarriage with blacks, that the Church would go on to destruction and the priesthood would be taken away.[161] The seed of Cain generally referred to those with dark skin who were of African descent.[4]:12 In 1863 during a sermon criticizing the federal government, Young said that the penalty for interracial reproduction between whites and blacks was death.[4]:43[162]:54

20th century

In 1946, J. Reuben Clark called racial intermarriage a "wicked virus" in an address in the church's official Improvement Era magazine.[140][16]:66 The next year, a California stake president Virgil H. Sponberg asked if members of the church are "required to associate with [Negroes]". The First Presidency under George Albert Smith sent a reply on May 5 stating that "social intercourse ... should certainly not be encouraged because of leading to intermarriage, which the Lord has forbidden."[139][16]:42 Two months later in a letter to Utah State sociology professor Lowry Nelson,[86] the First Presidency stated that marriage between a black person and a white person is "most repugnant" and "does not have the sanction of the Church and is contrary to church doctrine".[163]:276[138][164] Two years later in response to inquiries from a member Mrs. Guy B. Rose about whether white members were required to associate with black people the apostle Clark wrote that the church discouraged social interaction with black people since it could lead to marriage with them and interracial children.[4]:171[150][165]

Church apostle Mark E. Petersen said in a 1954 address that he wanted to preserve the purity of the white race and that blacks desired to become white through intermarriage. The speech was circulated among BYU religion faculty, much to embarrassment of fellow LDS scholars. Over twenty years later Petersen denied knowing if the copies of his speech being passed around were authentic or not, apparently out of embarrassment.[4]:68–69[33] In 1958, church general authority Bruce R. McConkie published Mormon Doctrine in which he stated that "the whole negro race have been cursed with a black skin, the mark of Cain, so they can be identified as a caste apart, a people with whom the other descendants of Adam should not intermarry."[4]:73 The quote remained, despite many other revisions,[4]:73 until the church's Deseret Book ceased printing the book in 2010.[166]

Utah's anti-miscegenation law was repealed in 1963 by the Utah state legislature.[46]:258 In 1967, the Supreme Court ruling on the case of Loving v. Virginia determined that any prohibition of interracial marriages in the United States was unconstitutional.[167]

In a 1965 address to BYU students, apostle Spencer W. Kimball advised BYU students on interracial marriage: "Now, the brethren feel that it is not the wisest thing to cross racial lines in dating and marrying. There is no condemnation. We have had some of our fine young people who have crossed the lines. We hope they will be very happy, but experience of the brethren through a hundred years has proved to us that marriage is a very difficult thing under any circumstances and the difficulty increases in interrace marriages."[168] A church lesson manual for boys 12–13, published in 1995, contains a 1976 quote from Spencer W. Kimball that recommended the practice of marrying others of similar racial, economic, social, educational, and religious backgrounds.[169]:169[170] In 2003, the church published the Eternal Marriage Student Manual, which used the same quote.[171]

Even after the temple and priesthood ban was lifted for black members in 1978 the church still officially discouraged any marriage across ethnic lines, though it no longer banned or punished it.[58]:5[172]

21st century

Until 2013 at least one official church manual in use had continued encouraging members to marry other members of the same race.[173][174][175] Speaking on behalf of the church, Robert Millet wrote in 2003: "[T]he Church Handbook of Instructions ... is the guide for all Church leaders on doctrine and practice. There is, in fact, no mention whatsoever in this handbook concerning interracial marriages. In addition, having served as a Church leader for almost 30 years, I can also certify that I have never received official verbal instructions condemning marriages between black and white members."[176]

The first African-American called as a general authority of the Church, Peter M. Johnson, had a white wife, as did Ahmad Corbitt, the first African-American called as a general officer of the Church.[177]

Racial attitudes

Between the 19th and mid-20th centuries, some Mormons held racist views, and exclusion from priesthood was not the only discrimination practiced toward black people. With Joseph Smith as the mayor of Nauvoo, blacks were prohibited from holding office or joining the Nauvoo Legion.[160] Brigham Young taught that equality efforts were misguided, claiming that those who fought for equality among blacks were trying to elevate them "to an equality with those whom Nature and Nature's God has indicated to be their masters, their superiors", but that instead they should "observe the law of natural affection for our kind."[178]

A 1959 report by the US Commission found that blacks experienced the most wide-spread inequality in Utah, and Mormon teachings on blacks were used to explain racist teachings on blacks.[91] During the 1960s and 1970s, Mormons in the western United States were close to averages in the United States in racial attitudes.[23] In 1966, Armand Mauss surveyed Mormons on racial attitudes and discriminatory practices. He found that "Mormons resembled the rather 'moderate' denominations (such as Presbyterian, Congregational, Episcopalian), rather than the 'fundamentalists' or the sects."[179] Negative racial attitudes within Mormonism varied inversely with education, occupation, community size of origin, and youth, reflecting the national trend. Urban Mormons with a more orthodox view of Mormonism tended to be more tolerant.[179] The American racial attitudes caused difficulties when the church tried to apply the one-drop rule to other areas. For example, many members in Brazil did not understand American classifications of race and how it applied to the priesthood ban, causing a rift between the missionaries and members.[44]

Anti-black jokes commonly circulated among Mormons before the 1978 revelation.[180] In the early 1970s, apostle Spencer W. Kimball began preaching against racism. In 1972, he said: "Intolerance by church members is despicable. A special problem exists with respect to black people because they may not now receive the priesthood. Some members of the Church would justify their own un-Christian discrimination against black people because of that rule with respect to the priesthood, but while this restriction has been imposed by the Lord, it is not for us to add burdens upon the shoulders of our black brethren. They who have received Christ in faith through authoritative baptism are heirs to the celestial kingdom along with men of all other races. And those who remain faithful to the end may expect that God may finally grant them all blessings they have merited through their righteousness. Such matters are in the Lord's hands. It is for us to extend our love to all."[181] In a study covering 1972 to 1996, church members in the United States has been shown to have lower rates of approval of segregation than others from the United States, as well as a faster decline in approval of segregation over the periods covered, both with statistical significance.[58]:94–97

Today, the church actively opposes racism among its membership. It is currently working to reach out to black people, and has several predominantly black wards inside the United States.[182] It teaches that all are invited to come unto Christ and it speaks against those who harbor ill feelings towards another race. In 2006, church president Gordon B. Hinckley said in a General Conference of the church that those who use racial slurs can not be called disciples of Christ.[4]:132–135

In the July 1992 edition of the New Era, the church published a MormonAd promoting racial equality in the church. The photo contained several youth of a variety of ethic backgrounds with the words "Family Photo" in large print. Underneath the picture are the words "God created the races—but not racism. We are all children of the same Father. Violence and hatred have no place in His family. (See Acts 10:34.)"[183]

In August 2017, the LDS Church released a statement about the Unite the Right rally in Charlottesville, Virginia, condemning racism in general through its Public Relations Department.[184] Following the statement, the LDS Church released an additional statement, specifically condemning white supremacy as morally wrong. Black Mormon blogger Tami Smith said that she joyfully heard the statement and felt that the church was standing with black church members.[185][186] Alt-right Mormon blogger Ayla Stewart argues that the statement is non-binding since it came from the Public Relations Department, rather than the First Presidency.[187][186]

Opposition to race-based policies

In the second half of the 20th century some white LDS Church members protested against church teachings and policies excluding black members from temple ordinances and the priesthood. For instance, three members, John Fitzgerald, Douglas A. Wallace, and Byron Marchant, were all excommunicated by the LDS Church in the 1970s for publicly criticizing these teachings (in the years 1973, 1976, and 1977 respectively).[123]:345–346 Wallace had given the priesthood to a black man on April 2, 1976 without authorization and the next day attempted to enter the general conference to stage a demonstration. After being legally barred from the following October conference, his house was put under surveillance during the April 1977 conference by police at the request of the LDS church and the FBI.[4]:107[188] Marchant was excommunicated for signaling the first vote in opposition to sustaining the church president in modern history during the April 1977 general conference. His vote was motivated by the temple and priesthood ban.[4]:107–108[189] He had also received previous media attention as an LDS scoutmaster of a mixed-faith scout troop involved in a 1974 lawsuit that changed the church's policy banning even non-Mormon black Boy Scouts from acting as patrol leaders as church-led scouting troop policy had tied scouting position with Aaronic Priesthood authority.[190][124][191]

Other white members who publicly opposed church teachings and policies around black people included Grant Syphers and his wife, who were denied access to the temple over their objections, with their San Francisco bishop stating that "Anyone who could not accept the Church's stand on Negroes ... could not go to the temple." Their stake president agreed and they were denied the temple recommend renewal.[192] Additionally, Prominent LDS politician Stewart Udall, who was then acting as the United States Secretary of the Interior, wrote a strongly worded public letter in 1967 criticizing LDS policies around black members[193][194] to which he received hundreds of critical response letters, including ones from apostles Delbert Stapley and Spencer Kimball.[163]:279–283

Racial discrimination after the 1978 revelation

LDS historian Wayne J. Embry interviewed several black LDS Church members in 1987 and reported that all the participants reported "incidents of aloofness on the part of white members, a reluctance or a refusal to shake hands with them or sit by them, and racist comments made to them." Embry further reported that one black church member attended church for three years, despite being completely ignored by fellow church members. Embry reports that "she [the same black church member] had to write directly to the president of the LDS Church to find out how to be baptized" because none of her fellow church members would tell her.[58]:371

Despite the end of the priesthood ban in 1978, and proclamations from church leadership extolling diversity, racist beliefs in the church prevailed. White church member Eugene England, a professor at Brigham Young University, wrote in 1998 that most Mormons still held deeply racist beliefs, including that blacks were descended from Cain and Ham and subject to their curses. England's students at BYU who reported these beliefs learned them from their parents or from instructors at church, and had little insight into how these beliefs contradicted gospel teachings.[195] In 2003, black LDS Church member Darron Smith noticed a similar problem, and wrote in Sunstone about the persistence of racist beliefs in the LDS church. Smith wrote that racism persisted in the church because church leadership had not addressed the ban's origins. This racism persisted in the beliefs that blacks were descendants of Cain, that they were neutral in the war in heaven, and that skin color was tied to righteousness.[196] In 2007, journalist and church member, Peggy Fletcher Stack, wrote that black Mormons still felt separate from other church members because of how other members treat them, ranging from calling them the "n-word" at church and in the temple to small differences in treatment. The dearth of blacks in LDS Church leadership also contributes to black members' feelings of not belonging.[197][198]

in June 2016, Alice Faulkner Burch—a women's leader in the Genesis Group, an LDS-sponsored organization for black Mormons in Utah—said black Mormons "still need support to remain in the church—not for doctrinal reasons but for cultural reasons." Burch added that "women are derided about our hair ... referred to in demeaning terms, our children mistreated, and callings withheld." When asked what black women today want, Burch recounted that one woman had told her she wished "to be able to attend church once without someone touching my hair."[199]

In 2020, a printed Sunday school manual that accompanied an LDS course studying the Book of Mormon contained teachings about “dark skin” as constituting a “curse” and a sign of divine disfavor.[200] After a public outcry, the church corrected its digital version of the manual of the course, titled “Come, Follow Me”, and apostle Gary E. Stevenson told a Martin Luther King Day gathering of the NAACP that he was “saddened” by the error,[201] adding: “We are asking members to disregard the paragraph in the printed manual.”[202] BYU law professor Michalyn Steele, a Native American, later expressed concern about the church's editorial practice and dismay that church educators continue to perpetuate racism.[201]

In the summer of 2020, Russell M. Nelson issued a joint statement with three top leaders of the NAACP condemning racism and calling for all institutions to work to remove any lingering racism.[203] In the October 2020 general conference, Nelson, his first counselor Dallin H. Oaks, and apostle Quentin L. Cook all denounced racism in their talks.[204]

In response to a 2016 survey of self-identified Mormons, over 60% expressed that they either know (37 percent) or believe (25.5 percent) that the priesthood/temple ban was God's will, with another 17 percent expressing that it might be true, and 22 percent saying they know or believe it is false.[205]

Black membership

The first statement regarding proselyting towards blacks was about slaves. In 1835, the Church's policy was to not proselyte to slaves unless they had permission from their masters. This policy was changed in 1836, when Smith wrote that slaves should not be taught the gospel at all until after their masters were converted.[16]:14 Though the church had an open membership policy for all races, they avoided opening missions in areas with large black populations, discouraged people with black ancestry from investigating the church,[44]:27[7]:76 counseled members to avoid social interactions with black people,[8]:89 and instructed black members to segregate when white members complained of having to worship with them.[4]:67–68 Relatively few black people who joined the church retained active membership prior to 1978.[206]

Proselytization

Bruce R. McConkie stated in his 1966 Mormon Doctrine that the "gospel message of salvation is not carried affirmatively to them, although sometimes negroes search out the truth."[207][58]:12 Despite interest from a few hundred Nigerians, proselyting efforts were delayed in Nigeria in the 1960s. After the Nigerian government stalled the church's visa, apostles did not want to proselyte there.[7]:85–87; 94 In Africa, there were only active missionaries among whites in South Africa. Blacks in South Africa who requested baptism were told that the church was not working among the blacks.[7]:76 In the South Pacific, the church avoiding missionary work among native Fijians until 1955 when the church determined they were related to other Polynesian groups.[7]:80 In Brazil, LDS officials discouraged individuals with black ancestry from investigating the church. Prior to WWII, proselytization in that country was limited to white German-speaking immigrants.[208] The church instituted a mission-wide genealogy program to discover black ancestry, and their official records were marked if any black ancestry was discovered.[209]:27 In the 1970s, "lineage lessons" were added to determine that interested persons were eligible for teaching.[4]:102[210] After 1978, there were no restrictions against proselytizing to blacks. Shortly after, missionaries began entering areas of Africa that were more predominately black.

After 1978

The church does not currently keep official records on the race of its membership,[46]:269 so exact numbers are unknown. Black people have been members of Mormon congregations since its foundation, but in 1964 its black membership was small, with about 300 to 400 black members worldwide.[211] In 1970, the officially sanctioned black LDS support group, the Genesis Group, was formed in Salt Lake City, Utah.[4]:84 In 1997, there were approximately 500,000 black members of the church (about 5% of the total membership), mostly in Africa, Brazil and the Caribbean.[212] Since then, black membership has grown, especially in West Africa, where two temples have been built,[213] doubling to about 1 million black members worldwide by 2008.[211]

In April 2017, the LDS Church announced plans to build a temple in Nairobi, Kenya, bringing the number of temples planned or built in Africa outside South Africa to six.[214] In 2017, two black South African men were called to serve as mission presidents.[215] Under President Russell M. Nelson, the pace of announcement of new temples across Africa picked up. During his first two years as president of the Church, five additional temples were announced for Africa, including two in Nigeria (bringing that country to a total of three temples in some stage of operation or planning), one in the Democratic Republic of the Congo (which was the quickest announcement of a second temple after the dedication of the first for any country other than the United States), and the first temples in Sierra Leone and Cape Verde. Nelson also announced temples in San Juan, Puerto Rico and Salvador, Brazil, both places where large percentages of both church members and the overall population were of African descent.

Professor Philip Jenkins noted in 2009 that LDS growth in Africa has been slower than that of other churches due to a number of reasons: one being the white face of the church due to the priesthood ban, and another being the church's refusal to accommodate local customs like polygamy.[216]:2,12

As of 2020, there had been six men of African descent called as general authorities and one called as a general officer of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints. Of these seven men, one was called while Ezra Taft Benson was president of the Church, two during Thomas S. Monson's ten-year tenure as president of the church and four during the first two years Russell M. Nelson was president of the Church.

Other Latter Day Saint groups' positions

Community of Christ

Joseph Smith III, the son of Joseph Smith, founded the Reorganized Church of Jesus Christ of Latter Day Saints in 1860, now known as the Community of Christ. Smith was a vocal advocate of abolishing the slave trade, and a supporter of Owen Lovejoy, an anti-slavery congressman from Illinois, and Abraham Lincoln. He joined the Republican Party and advocated its antislavery politics. He rejected the fugitive slave law, and openly stated that he would assist slaves who tried to escape.[217] While he was a strong opponent of slavery, he still viewed whites as superior to blacks, and held the view that they must not "sacrifice the dignity, honor and prestige that may be rightfully attached to the ruling races."[218] The priesthood has always been open to men of all races, and it has also been open to women since 1984. The Community of Christ rejects the Pearl of Great Price, especially its teachings on priesthood restrictions.[219]

Fundamentalist Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-Day Saints

Warren Jeffs, President of the Fundamentalist Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-Day Saints since 2002,[220] has made several documented statements on black people including the following:

- "The black race is the people through which the devil has always been able to bring evil unto the earth."

- "[Cain was] cursed with a black skin and he is the father of the Negro people. He has great power, can appear and disappear. He is used by the devil, as a mortal man, to do great evils."

- "Today you can see a black man with a white woman, et cetera. A great evil has happened on this land because the devil knows that if all the people have Negro blood, there will be nobody worthy to have the priesthood."

- "If you marry a person who has connections with a Negro, you would become cursed."[221]

Bickertonite

The Church of Jesus Christ (Bickertonite) has advocated full racial integration throughout all aspects of the church since its organization in 1862. While America was engaged in disputes over the issues of civil liberties and racial segregation, the church said that its message was open to members of all races.[222] In 1905, the church suspended an elder for opposing the full integration of all races.[223]

Historian Dale Morgan wrote in 1949: "An interesting feature of the Church's doctrine is that it discriminates in no way against ... members of other racial groups, who are fully admitted to all the privileges of the priesthood. It has taken a strong stand for human rights, and was, for example, uncompromisingly against the Ku Klux Klan during that organization's period of ascendancy after the First World War."[224]

At a time when racial segregation or discrimination was commonplace in most institutions throughout America, two of the most prominent leaders of The Church of Jesus Christ were African American. Apostle John Penn, a member of the Quorum of the Twelve from 1910 to 1955, conducted missionary work among Italian Americans, and he was often referred to as "The Italian's Doctor".[223] Matthew Miller, who was ordained an evangelist in 1937, traveled throughout Canada and established missions to Native Americans.[223] The Church does not report any mission involvement or congregations in predominantly black countries.

Strangite

Strangites welcomed African Americans into their church during a time when some other factions denied them the priesthood, and certain other benefits that come with membership in it. Strang ordained at least two African Americans to his church's eldership during his lifetime.[225]

See also

References

- Peggy Fletcher Stack (2007). "Faithful witness". The Salt Lake Tribune.

- Hale, Lee (May 31, 2018). "Mormon Church Celebration Of 40 Years Of Black Priesthood Brings Up Painful Past". All Things Considered. NPR.

- Embry, Jessie (1994). Black Saints in a White Church. Salt Lake City, Utah: Signature Books. ISBN 1-56085-044-2. OCLC 30156888.

- Harris, Matthew L.; Bringhurst, Newell G. (2015). The Mormon Church and Blacks: A Documentary History. Chicago: University of Illinois Press. ISBN 978-0-252-08121-7.

- Bates, Irene M. (1993). "Patriarchal Blessings and the Routinization of Charisma" (PDF). Dialogue. 26 (3). Retrieved November 13, 2017.

- Anderson, Devery S. (2011). The Development of LDS Temple Worship, 1846-2000: A Documentary History. Salt Lake City: Signature Books. p. xlvi. ISBN 9781560852117.

- Prince, Gregory A. (2005). David O. McKay and the Rise of Modern Mormonism. Salt Lake City, Utah: University of Utah Press. ISBN 0-87480-822-7.

- Bush, Lester E. Jr.; Mauss, Armand L., eds. (1984). Neither White Nor Black: Mormon Scholars Confront the Race Issue in a Universal Church. Salt Lake City, Utah: Signature Books. ISBN 0-941214-22-2.

- Mauss 2003, p. 238

- Kidd, Colin (2006). The Forging of Races: Race and Scripture in the Protestant Atlantic World, 1600–2000. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 9780521793247.

- Official Declaration 2.

- Ballard, President M. Russell, et al. "Race and the Priesthood." The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, www.churchofjesuschrist.org/study/manual/gospel-topics-essays/race-and-the-priesthood?lang=eng.

- "Saints, Slaves, and Blacks" by Bringhurst. Table 8 on p.223

- Coleman, Ronald G. (2008). "'Is There No Blessing For Me?': Jane Elizabeth Manning James, a Mormon African American Woman". In Taylor, Quintard; Moore, Shirley Ann Wilson (eds.). African American Women Confront the West, 1600–2000. Norman, Oklahoma: University of Oklahoma Press. pp. 144–162. ISBN 978-0-8061-3979-1.

Jane Elizabeth James never understood the continued denial of her church entitlements. Her autobiography reveals a stubborn adherence to her church even when it ignored her pleas.

- Mauss, Armand L. (2003). All Abraham's Children: Changing Mormon Conceptions of Race and Lineage. University of Illinois Press. p. 213. ISBN 0-252-02803-1.

At least until after Smith's death in 1844, then, there seems to have been no church policy of priesthood denial on racial grounds, and a small number of Mormon blacks were actually given the priesthood. The best known of these, Elijah Abel, received the priesthood offices of both elder and seventy, apparently in the presence of Smith himself.

- Bush, Lester E. (1973). "Mormonism's Negro Doctrine: An Historical Overview" (PDF). Dialogue. 8 (1).

- Bush, Lester E. Mormonism's Negro Doctrine: an Historical Overview. 1978.

- Mahas, Jeffrey D. “Ball, Joseph T.” Century of Black Mormons · Ball, Joseph T. · J. Willard Marriott Library Exhibits, exhibits.lib.utah.edu/s/century-of-black-mormons/page/ball-joseph-t.

- Bennett, Rick. “Peter ‘Black Pete’ Kerr (Ca. 1775-Ca. 1840).” Blackpast, 17 May 2020, www.blackpast.org/african-american-history/kerr-peter-black-pete-1810-1840/.

- Kiser, Benjamin. “Flake, Green.” Century of Black Mormons · Flake, Green · J. Willard Marriott Library Exhibits, exhibits.lib.utah.edu/s/century-of-black-mormons/page/flake-green.

- Riess, Jana. “Black Mormon Pioneer Jane Manning James Finally Gets Her Due.” Religion News Service, 21 Nov. 2019, religionnews.com/2019/06/13/black-mormon-pioneer-jane-manning-james-finally-gets-her-due/.

- Embry 1994: 40-41.

- Mauss, Armand (2003). "The LDS Church and the Race Issue: A Study in Misplaced Apologetics". FAIR.

- Brigham Young, Speeches Before the Utah Territorial Legislature, Jan. 23 and Feb. 5, 1852, George D. Watt Papers, Church History Library, Salt Lake City, transcribed from Pitman shorthand by LaJean Purcell Carruth; “To the Saints,” Deseret News, April 3, 1852, 42.

- Watt, G. D.; Long, J. V. (1855). "The Constitution and Government of the United States—Rights and Policy of the Latter-Day Saints". In Young, Brigham (ed.). Journal of Discourses Vol. 2. Liverpool: F. D. Richards. ISBN 978-1-60096-015-4.