Blessed sword and hat

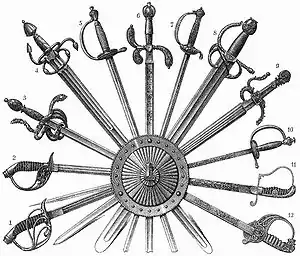

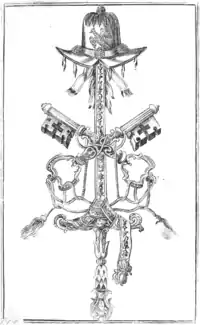

The blessed sword (Latin: ensis benedictus, Italian: stocco benedetto[1] or stocco pontificio[2]) and the blessed hat (also: ducal hat,[3] Latin: pileus or capellus,[4] Italian: berrettone pontificio[5] or berrettone ducale[6]) were a gift offered by popes to Catholic monarchs or other secular recipients in recognition of their defence of Christendom. Each pair was blessed by a pope on Christmas Eve in St. Peter's Basilica in Rome. The sword was an ornate ceremonial weapon, usually large, up to 2 metres long, with the hilt embellished with the pope's coat of arms, and the blade with the pope's name. A similarly ornate scabbard and belt were added to the sword. The hat was a cylinder made of red velvet with two lappets hanging down from its top. The right-hand side of the hat was decorated with a dove representing the Holy Spirit embroidered in pearls, while a shining sun symbolising Christ was embroidered in goldwork on the top.[7]

| Blessed sword | |

|---|---|

A blessed sword with a belt and a blessed hat received by Manuel Pinto da Fonseca in 1747, with the Keys of Heaven in the foreground | |

| Type | Ceremonial sword |

| Place of origin | |

| Service history | |

| In service | 14th–19th centuries |

The earliest preserved blessed sword, now located at the Royal Armory in Madrid, was given by Pope Eugene IV to King John II of Castile in 1446. The latest preserved of the blessed swords, now at the National Museum of the Middle Ages in Paris, was blessed in 1772 by Pope Clement XIV and presented to Francisco Ximenes de Texada, grand master of the Knights Hospitaller.[7] Not all recipients are known; among those whose names have been preserved, there were at least twelve emperors of the Holy Roman Empire, ten kings of France, seven kings of Poland, and six kings of Spain. Additionally, three or four blessed swords and hats were given to kings of England, two or three to kings of Scots, and three each to the kings of Hungary and Portugal. Recipients also included various princes, including heirs-apparent, archdukes, dukes, noblemen, military commanders, as well as cities and states.[8]

History

The tradition of distributing blessed swords and hats by the popes is not as old as that of another papal gift, the golden rose, but it does date back at least as far back as the 14th century. The earliest recipient of a pontifical sword and hat who is known for certain was Fortiguerra Fortiguerri, a gonfaloniere of the Republic of Lucca, who received it from Pope Urban VI in 1386. However, papal account books record payments for the manufacture of such gifts as early as 1357, and even then it seems to have been a long-established practice.[9] Some historians push the origin of the tradition even further back. According to Gaetano Moroni, Pope Innocent III presented a sword and hat to King William the Lion of the Scots in 1202.[10] Lord Twining dismissed this proposition as legendary, but accepted that the tradition originated with Pope Paul I's gift of a sword to King Pepin the Short of the Franks in 758.[11]

Starting with the pontificate of Pope Martin V (reigned 1417–1431), detailed payment records exist for the manufacture of swords and hats for every year, although the recipients are not always known. During the 15th century, popes gradually moved from the practice of presenting the swords and hats to noblemen or princes visiting Rome at Christmas time towards sending them to distant monarchs as either reward or encouragement to defend Christendom and the interests of the Catholic Church. The practice accelerated under Pope Nicholas V (r. 1447–1455), who used the gifts to promote a military alliance against the Ottoman Empire.[12]

Description

| Item | Cost |

|---|---|

| Blessed sword with scabbard and belt | |

| Blade (ready-made) | 3.00 ƒ |

| Wooden frame of the scabbard | 0.50 ƒ |

| Silver for the grip, pommel and the filigree work on the scabbard | 90.00 ƒ |

| Gilding of the sword and scabbard | 20.00 ƒ |

| Crimson lining of the scabbard | 2.00 ƒ |

| Cloth of gold for the belt | 15.00 ƒ |

| Silver for the clasp and buckle of the belt | 15.00 ƒ |

| Manufacture of the sword, scabbard and belt | 30.00 ƒ |

| Blessed hat | |

| Pearls | 35.00 ƒ |

| Ermines | 6.00 ƒ |

| Embroidery | 5.00 ƒ |

| Gold band | 5.00 ƒ |

| Manufacture of the hat | 4.00 ƒ |

| Total | 230.50 ƒ |

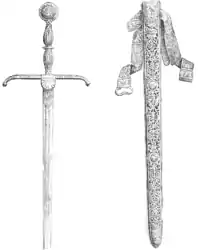

The blessed sword was always a two-handed one,[14] sometimes more than 2 metres (7 ft) long.[7] The hilt was made of silver and covered with elaborate repoussage in gold.[14] The pommel was decorated with the pope's coat of arms surrounded with images of the papal tiara and pallium. The blade was embellished with intricate engravings. They included an inscription running along the length of the blade, indicating the pope's name and in which year of his pontificate the sword was blessed. The accompanying scabbard and belt were similarly sumptuous and ornate, covered in velvet and studded with precious stones,[3] and also bore the papal coat of arms. The identity of the recipient, on the other hand, was never indicated on the sword in any way. This practice stemmed from the Church's stance that the pope himself was the true defender of the faith, while the prince bestowed with the sword was merely the pontiff's armed arm.[7] The symbolic significance of the sword was connected to the papal claim to both supreme spiritual and temporal power, derived from the Biblical story of Saint Peter using a sword to protect Jesus during his arrest in the Garden of Olives.[15]

The hat had the form of a stiff high cylinder surrounded by a deep brim, which curved upwards to a point at the front. In the back hanged two lappets, similar to those in a bishop's mitre.[16] The hat was made of beaver pelt[3] or velvet, typically dark crimson in color, although grey and black are also mentioned in some accounts. It was sometimes lined with ermine. A haloed dove, symbolizing the Holy Spirit, was embroidered in goldwork and adorned with pearls on the right hand side of the cylinder. On top of the hat, a shining sun with alternatively straight and wavy rays that descended towards the brim, was likewise picked out in gold thread.[16] The image of a dove symbolized the Holy Spirit protecting and guiding whomever was wearing the hat.[3][15] The Holy Spirit together with Christ the Sun God may also be interpreted as symbolic references to God's incarnation, a mystery celebrated on Christmas, on the eve of which the hat and the sword were blessed by a pope.[7]

Ten blessed swords from the 15th century have survived to present times, and about a dozen from the 16th century, although in some cases only the blade remains, while the more valuable hilt and scabbard have been lost. The hats, made of less durable materials, have been preserved in still smaller numbers, the earliest being from the second half of the 16th century. It is even impossible to ascertain whether the hat had always accompanied the sword from the beginning of the tradition or if it was a later addition.[14]

Ceremony

Popes used to bless the sword and the hat on every Christmas Eve. The blessing took place just before the matins in a simple ceremony conducted by the pope either in one of the private chapels of the papal palace or in the sacristy of St. Peter's Basilica. The pope, vested in an alb, amice, cincture and white stole, blessed both items held before him by a kneeling chamberlain by reciting a short prayer, the earliest form of which is attributed to Sixtus IV (r. 1471–1481). Then, the pope sprinkled the sword and hat with holy water and incensed them thrice before putting on a cappa, a long train of crimson silk, and proceeding to the basilica.[17]

If the person whom the pope intended to award with the blessed sword and hat was present, he was invested with them immediately. Dressed in a surplice over his secular robes, the recipient was brought before the pope, who addressed him with Sixtus IV's brief Solent Romani pontifices, explaining the symbolism of the gift.[18][19] It ended with the following words:

- "[...] we appoint you, holy prince, as another sword of the Holy See, which has, we declare by this fine gift, a most devout son in you, and also by this hat we declare that you are a fortification and bulwark to protect the holy Roman Church against the enemies of the Faith. Therefore, may your hand remain firm against the enemies of the Holy See and of the name of Christ, and may your right hand be lifted up, intrepid warrior, as you remove them from the earth, and may your head be protected against them by the Holy Spirit, symbolized by the pearly dove, in those things deemed worthy by the Son of God, together with the Father and the Holy Spirit. Amen."[20]

The sword was then girded over the recipient's surplice and he was dressed in a white cope. The morsel of the cope was fastened on his right shoulder so as to free his arm for drawing the sword later in the ceremony. The prince kissed the pope's hand and slipper as a sign of obeisance and, with his sword and hat, joined the procession to the basilica.[21] During the matins, the recipient sang the fifth lesson,[22] beginning with the words In quo conflictu pro nobis inito, taken from the homily of Saint Leo.[23] An exception was made for emperors, who sang the seventh lesson,[19] which begins with a quote from the Biblical account of the Census of Quirinius, Exiit edictum a Caesare Augusto ut describeretur universus orbis ("In those days a decree went out from Emperor Augustus that all the world should be registered"; Luke 2, Luke 2:1), deemed more appropriate because of the imperial connection.[24] Before singing the lesson, the prince removed his hat and handed it to his servant, then unsheathed the sword, struck it against the ground three times, then brandished it in the air, again three times, and replaced it in the scabbard. As the matins ended, the recipient took leave of the pope and returned to his residence in Rome, preceded by a man-at-arms carrying the blessed sword and hat, and followed by cardinals, prelates, papal chamberlains, ambassadors to the Holy See, friends and retinue.[25]

If the prospective honoree was absent at the ceremony, the sword and hat, after being blessed, were carried by the chamberlain before the cross in the procession and placed on the epistle side of the altar in the basilica.[8] The gifts were then dispatched by the pope by a special emissary to present them to their intended recipient in a ceremony extra curiam. The protocol was modelled on that prescribed for bestowing the golden rose outside Rome.[25] The emissary, entrusted with the sword and hat, instructed about the proper protocol, equipped with the pope's letter to the honoree, as well as a safe conduct pass, set out with a small retinue, usually in the spring following the blessing ceremony. When the emissary was within a day's journey from his destination, the recipient was expected to send forth a delegation to escort the emissary to his lodgings. The papal brief was delivered to the prince who then had to choose the venue and date of the ceremony. Typically, the ceremony took place on a Sunday or a major feast day in a cathedral or the major church of the town. A solemn mass was celebrated either by the emissary or by a local bishop or abbot indicated by the pope. The pope's letter was solemnly read during the mass, following which the prince received the blessed sword and hat from the hands of the celebrant. When the ceremony was over, the recipient returned to his residence in a procession, as it would happen in Rome.[26]

Recipients

| Year of blessing | Year of bestowal | Pope | Recipient | Notes | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1202 | Innocent III | William the Lion, king of Scots | Disputed | Burns 1969, pp. 161–162 | |

| 1204 | Innocent III | Peter II, king of Aragon | Disputed | Burns 1969, pp. 151, 162 | |

| 1347 | 1347 | Clement VI | Charles IV, emperor of the Holy Roman Empire | Uncertain | Burns 1969, p. 161 |

| 1365 | 1365 | Urban V | Louis I, duke of Anjou | Presented personally | Müntz 1889, p. 409; Warmington 2000, p. 109 |

| 1366 | 1366 | Urban V | John I, count of Armagnac | Presented personally | Müntz 1889, p. 409 |

| 1371 | 1371 | Gregory XI | Louis I, duke of Anjou (again) | Presented personally | Müntz 1889, pp. 409–410 |

| 1386 | 1386 | Urban VI | Fortiguerra Fortiguerri, gonfaloniere of the Republic of Lucca | Burns 1969, p. 160; Pinti 2001, p. 3 | |

| 1419 | Martin V | Charles, dauphin of France (future King Charles VII) | Uncertain | Warmington 2000, p. 109 | |

| 1422 | Martin V | Louis III, king of Naples | Warmington 2000, p. 109 | ||

| 1432 | Eugene IV | Władysław II Jagiełło, king of Poland | Disputed | Lileyko 1987, p. 123 | |

| 1434 | Eugene IV | Republic of Florence | Müntz 1890, p. 281 | ||

| 1443 | Eugene IV | Vladislaus III, king of Poland and Hungary | Probably lost in the Battle of Varna | Warmington 2000, p. 110; Lileyko 1987, p. 123 | |

| 1446 | Eugene IV | John II, king of Castile | Oldest preserved blessed sword, at the Royal Palace of Madrid, Spain | Warmington 2000, p. 110; Lileyko 1987, p. 123 | |

| 1449 | 1450 | Nicholas V | Francesco Foscari, doge of Venice | Blade preserved at the Doge's Palace in Venice, Italy | Warmington 2000, p. 110; Pinti 2001, p. 4 |

| 1450 | 1450 | Nicholas V | Albert VI, archduke of Austria | Warmington 2000, p. 110; Pinti 2001, p. 7 | |

| 1454 | Nicholas V | Count of Sant'Angelo, ambassador of Naples | Presented personally | Warmington 2000, p. 110 | |

| 1454 | 1455 | Nicholas V | Ludovico Bentivoglio, ambassador of Bologna | Sword and scabbard preserved at the Medieval Museum of Bologna, Italy | Müntz 1890, p. 283; Pinti 2001, pp. 4, 19 |

| 1456 | 1457 | Calixtus III | Charles VII, king of France | Warmington 2000, pp. 123–128 | |

| 1457 | 1458 | Calixtus III | Henry IV, king of Castile | Blade preserved at the Royal Palace of Madrid, Spain | Warmington 2000, pp. 123–128; Müntz 1890, p. 284 |

| 1458 | 1459 | Pius II | Frederick III, emperor of the Holy Roman Empire | Warmington 2000, pp. 123–128 | |

| 1459 | 1460 | Pius II | Albert III Achilles, margrave of Brandenburg-Ansbach | Presented personally at the Council of Mantua. The sword later became the Electoral Sword (Kurschwert) of Brandenburg, preserved at the Charlottenburg Palace in Berlin, Germany | Warmington 2000, pp. 123–128; Kühn 1967 |

| 1460 | 1461 | Pius II | Philip the Good, duke of Burgundy | Warmington 2000, pp. 123–128 | |

| 1461 | 1462 | Pius II | Louis XI, king of France | Warmington 2000, pp. 123–128 | |

| 1462 | 1463 | Pius II | Cristoforo Moro, doge of Venice | Blade preserved at the Doge's Palace in Venice, Italy | Warmington 2000, pp. 123–128; Pinti 2001, p. 4 |

| 1466 | 1466 | Pius II | Skanderbeg, lord of Albania | Presented personally | Warmington 2000, pp. 123–128 |

| 1467 or 1469 | Paul II | Henry IV, king of Castile | Warmington 2000, pp. 123–128 | ||

| 1468 | 1468 | Paul II | Frederick III, emperor of the Holy Roman Empire | Presented personally | Warmington 2000, pp. 123–128 |

| 1470 | 1471 | Paul II | Matthias Corvinus, king of Hungary | Warmington 2000, pp. 123–128 | |

| 1471 | Paul II | Borso d'Este, duke of Ferrara | Presented personally | Warmington 2000, pp. 123–128 | |

| 1474 | 1475 | Sixtus IV | Philibert I, duke of Savoy | Warmington 2000, pp. 123–128 | |

| 1477 | 1477 | Sixtus IV | Alfonso, duke of Calabria (future King Alfonso II of Naples) | Presented personally | Warmington 2000, pp. 123–128 |

| 1480 | 1480 | Sixtus IV | Federico da Montefeltro, duke of Urbino | Warmington 2000, pp. 123–128 | |

| 1481 | 1482 | Sixtus IV | Edward IV, king of England | Warmington 2000, pp. 123–128 | |

| 1482 | 1482 | Sixtus IV | Alfonso, duke of Calabria (future King Alfonso II of Naples, again) | Presented personally | Warmington 2000, pp. 123–128 |

| 1484 | 1484 | Innocent VIII | Francesco of Aragon, ambassador of Naples | Presented personally | Warmington 2000, pp. 123–128 |

| Between 1484 and 1492 | Innocent VIII | Ferdinand II, king of Aragon | Warmington 2000, pp. 123–128 | ||

| 1486 | 1486 | Innocent VIII | Enea López de Mendoza, count of Tendilla, ambassador of Castile and Aragon | Presented personally | Warmington 2000, pp. 123–128 |

| 1488 | 1488 | Innocent VIII | Giovanni Giacomo Trivulzio, general of the ecclesiastical army | Presented personally | Warmington 2000, pp. 123–128 |

| 1491 | 1491 | Innocent VIII | William III, landgrave of Hesse | Presented personally | Warmington 2000, pp. 123–128 |

| 1492 | 1492 | Alexander VI | Frederick, crown prince of Naples (future King Frederick IV) | Presented personally | Warmington 2000, pp. 123–128 |

| 1493 | 1494 | Alexander VI | Maximilian I, king of the Romans | Warmington 2000, pp. 123–128 | |

| 1494 | 1494 | Alexander VI | Ferdinand, duke of Calabria | Presented personally | Warmington 2000, pp. 123–128 |

| 1496 | 1497 | Alexander VI | Philip the Fair, archduke of Austria | Warmington 2000, pp. 123–128 | |

| 1497 | 1497 | Alexander VI | Bogislaw X, duke of Pomerania | Presented personally. Used as part of ducal insignia by subsequent dukes of Pomerania. | Warmington 2000, pp. 123–128; Lileyko 1987, p. 124 |

| 1498 | 1499 | Alexander VI | Louis XII, king of France | Warmington 2000, pp. 123–128 | |

| 1500 | Alexander VI | Cesare Borgia, duke of Valentinois, pope's son | Sword and scabbard preserved | Burns 1969, p. 163 | |

| 1501 | 1502 | Alexander VI | Alfonso d'Este, heir to the Duchy of Ferrara, pope's son-in-law | Warmington 2000, pp. 123–128 | |

| 1506 | 1507 | Julius II | James IV, king of Scots | The sword later became the Scottish Sword of State, preserved, together with its scabbard and belt in Edinburgh Castle, Scotland | Burns 1969, pp. 172–173 |

| 1508 | 1509 | Julius II | Vladislaus II, king of Bohemia and Hungary | Sword preserved at the Hungarian National Museum in Budapest, Hungary | Lileyko 1987, p. 123; Burns 1969, p. 174 |

| 1510 | 1511 | Julius II | Switzerland | Sword preserved at the Swiss National Museum in Zurich | Burns 1969, p. 174; Pinti 2001, p. 4 |

| 1513 | Leo X | Henry VIII, king of England | Burns 1969, p. 180 | ||

| 1514 | Leo X | Manuel I, king of Portugal | Burns 1969, p. 180 | ||

| 1515 | Leo X | Republic of Florence (again) | Burns 1969, p. 180 | ||

| 1516 | Leo X | Francis I, king of France | Uncertain | Burns 1969, p. 180 | |

| 1517 | Leo X | Maximilian I, emperor of the Holy Roman Empire | Uncertain | Burns 1969, p. 180 | |

| 1525 | Clement VII | Sigismund I, king of Poland | Lost before 1669 | Lileyko 1987, p. 124 | |

| 1529 | Clement VII | Charles V, emperor of the Holy Roman Empire | Blade preserved at the Royal Palace of Madrid, Spain | Pinti 2001, p. 12 | |

| 1536 | 1537 | Paul III | James V, king of Scots | Lost between 1542 and 1556 | Burns 1969, pp. 181–183 |

| 1540 | Paul III | Sigismund II Augustus, king of Poland | Lost after 1795 | Lileyko 1987, p. 124 | |

| 1550 | Paul III | Philip, prince of Asturias (future King Philip II of Spain) | Blade preserved at the Royal Palace of Madrid, Spain | Pinti 2001, p. 12 | |

| 1555 | 1558 | Paul IV | Ercole II d'Este, duke of Ferrara | Sword preserved at the Konopiště Castle in Benešov, Czech Republic | Pinti 2001, pp. 12, 30 |

| 1560 | Pius IV | Philip II, king of Spain (again) | Blade preserved at the Royal Palace of Madrid, Spain | Pinti 2001, p. 12 | |

| 1563 | Pius IV | Carlos, prince of Asturias | Blade preserved at the Royal Palace of Madrid, Spain | Pinti 2001, p. 12 | |

| 1566 | Pius V | Fernando Álvarez de Toledo y Pimentel, 3rd Duke of Alba | Blade preserved at ? | Sampedro Escolar 2007, p. 97/8 | |

| 1567 | 1568 | Pius V | Ferdinand II, archduke of Further Austria | Sword and hat preserved | Pinti 2001, p. 6; Burns 1969, p. 163 |

| 1580 | Gregory XIII | Stephen Báthory, king of Poland | Blade preserved at the Wawel Castle in Kraków, Poland | Lileyko 1987, p. 124 | |

| 1581 | 1582 | Gregory XIII | Ferdinand II, archduke of Further Austria (again) | Sword and hat preserved in Vienna, Austria | Pinti 2001, p. 5; Burns 1969, p. 163 |

| 1591 | Gregory XIV | Philip, prince of Asturias (future King Philip III of Spain) | Blade preserved at the Royal Palace of Madrid, Spain | Pinti 2001, p. 12 | |

| 1594 | Clement VII | Philip II, king of Spain (again) | Blade preserved at the Royal Palace of Madrid, Spain | Pinti 2001, p. 12 | |

| 1618 | Paul V | Philip, prince of Asturias (future King Philip IV of Spain) | Pinti 2001, p. 12 | ||

| 1625 | Urban VIII | Vladislaus Sigismund, crown prince of Poland (future King Vladislaus IV) | Presented personally. Blade preserved at the Skokloster Castle in Sweden. | Lileyko 1987, pp. 124–125 | |

| 1672 | Clement X | Michael Korybut Wiśniowiecki, king of Poland | Lost after 1673 | Lileyko 1987, p. 126 | |

| 1674 | 1683 | Clement X | John III Sobieski, king of Poland | Sent by Innocent XI. Sword used by Emperor Nicholas I of Russia for his coronation as king of Poland in 1829. Blade, scabbard and hat preserved at the Wawel Castle in Kraków, Poland | Lileyko 1987, pp. 126–127 |

| 1689 | 1690 | Alexander VIII | Francesco Morosini, doge of Venice | Sword, scabbard and belt preserved in the treasury of St Mark's Basilica in Venice, Italy | Pinti 2001, pp. 4, 28 |

| 1726 | Benedict XIII | Frederick Augustus, crown prince of Poland (future King Augustus III) | Scabbard, belt and hat preserved at the Dresden Armory in Germany | Lileyko 1987, p. 129 | |

| 1747 | Benedict XIV | Manuel Pinto da Fonseca, grand master of the Knights Hospitaller | Petroschi & Rossi 1747 | ||

| 1772 | 1773 or 1775 | Clement XIV | Francisco Ximenes de Texada, grand master of the Knights Hospitaller | Sent by Pius VI. Latest preserved blessed sword, at the National Museum of the Middle Ages in Paris, France | Lileyko 1987, p. 123; Pinti 2001, p. 6 |

| 1823 | Leo XII | Louis Antoine, duke of Angoulême | Pinti 2001, p. 3 |

See also

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Blessed swords. |

References

- Müntz (1889), p. 408

- Pinti (2001), p. 3

- Warmington (2000), p. 109

- Müntz (1889), p. 409

- Pinti (2001), p. 4

- Moroni (1854), p. 39

- Lileyko (1987), p. 123.

- Burns (1969), p. 165

- Burns (1969), p. 160

- Burns (1969), p. 161

- Burns (1969), p. 162

- Warmington (2000), pp. 109–110

- Burns (1969), pp. 163–164

- Burns (1969), p. 163

- Burns (1969), p. 164

- Burns (1969), pp. 162–163

- Burns (1969), pp. 164–165

- Burns (1969), pp. 165–166

- Warmington (2000), p. 116

- Translated from Latin by Robert Levine, quoted in Warmington (2000, pp. 129–130)

- Burns (1969), p. 166

- Burns (1969), pp. 166–167

- The Dolphin (1902), p. 8

- Warmington (2000), p. 100

- Burns (1969), p. 167

- Burns (1969), p. 159

Sources

- Burns, Charles (1969). "Papal Gifts to Scottish Monarchs: The Golden Rose and the Blessed Sword". Innes Review. Edinburgh University Press. 20 (2). doi:10.3366/inr.1969.20.2.150. ISSN 0020-157X.

- Kühn, Margarete (1967). "Das Charlottenburger Schloß" [Charlottenburg Palace]. Die Geschichte Berlins (in German). Verein für die Geschichte Berlins e.V. Retrieved 2013-03-26.

- Lileyko, Jerzy (1987). Regalia polskie [Polish Regalia] (in Polish). Warsaw: Krajowa Agencja Wydawnicza. ISBN 83-03-02021-8.

- Moroni, Gaetano (1854). "Stocco e berrettone ducale" [Sword and ducal hat]. Dizionario di erudizione storico-ecclesiastica (in Italian). LXX. Venice: Tipografia Emiliana. pp. 39–61.

- Müntz, Eugène (1889). "Les Epées d'honneur distribuées par les papes pendant les XIVe, XVe et XVIe siècles (Premier article)" [Honorary Swords Distributed by the Popes During the 14th, 15th and 16th Centuries (Part 1)]. Revue de l'art chrétien (in French). Société de Saint Jean: 408–411.

- Müntz, Eugène (1890). "Les Epées d'honneur distribuées par les papes pendant les XIVe, XVe et XVIe siècles (Deuxième article)" [Honorary Swords Distributed by the Popes During the 14th, 15th and 16th Centuries (Part 2)]. Revue de l'art chrétien (in French). Société de Saint Jean: 281–292.

- Petroschi, Giovanni; Rossi, Antonio (1747). Relazione di quello, che si è praticato in occasione di avere la Santità di nostro signore pp. Benedetto XIV, mandato lo Stocco ed il Pileo benedetti a Sua Altezza Eminentissima il gran maestro fra d. Emmanuele Pinto, felicemente regnante [Report on the Sending by His Holiness Benedict XIV of a Blessed Sword and Hat to His Eminent Highness Grand Master Manuel Pinto] (in Italian). Rome: Stamperia di Antonio de' Rossi.

- Pinti, Paolo (2001). "Lo stocco pontificio: immagini e storia di un'arma" [The Papal Sword: Images and History of a Weapon] (PDF). Saggi di opologia (in Italian). Circolo culturale armigeri del Piave (12): 3–52.

- "The Liturgy of the Christmas Cycle". The Dolphin: An Ecclesiastical Review for Educated Catholics. New York, Philadelphia: The Dolphin Press. I. 1902.

- Warmington, Flynn (2000). "The Ceremony of the Armed Man: The Sword, the Altar, and the L'homme armé Mass". In Higgins, Paula (ed.). Antoine Busnoys: Method, Meaning, and Context in Late Medieval Music. Oxford University Press. pp. 89–130. ISBN 0-19-816406-8.