Bonsai

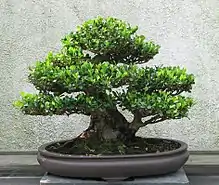

Bonsai (Japanese: 盆栽, lit. 'tray planting', pronounced [boɰ̃sai] (![]() listen))[1] is a Japanese art form which utilizes cultivation techniques to produce, in containers, small trees that mimic the shape and scale of full size trees. Similar practices exist in other cultures, including the Chinese tradition of penzai or penjing from which the art originated, and the miniature living landscapes of Vietnamese Hòn non bộ. The Japanese tradition dates back over a thousand years.

listen))[1] is a Japanese art form which utilizes cultivation techniques to produce, in containers, small trees that mimic the shape and scale of full size trees. Similar practices exist in other cultures, including the Chinese tradition of penzai or penjing from which the art originated, and the miniature living landscapes of Vietnamese Hòn non bộ. The Japanese tradition dates back over a thousand years.

%252C_con_frutti.jpg.webp)

| Bonsai | |||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

"Bonsai" in kanji | |||||||||||||||||||||||

| Chinese name | |||||||||||||||||||||||

| Chinese | 盆栽 | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| Literal meaning | "tray planting" | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||

| Korean name | |||||||||||||||||||||||

| Hangul | 분재 | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| Hanja | 盆栽 | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||

| Japanese name | |||||||||||||||||||||||

| Kanji | 盆栽 | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||

The loanword "bonsai" (a Japanese pronunciation of the earlier Chinese term penzai) has become an umbrella term in English, attached to many forms of potted or other plants,[2] and also on occasion to other living and non-living things. According to Stephen Orr in The New York Times, "the term should be reserved for plants that are grown in shallow containers following the precise tenets of bonsai pruning and training, resulting in an artful miniature replica of a full-grown tree in nature."[3] In the most restrictive sense, "bonsai" refers to miniaturized, container-grown trees adhering to Japanese tradition and principles.

Purposes of bonsai are primarily contemplation for the viewer, and the pleasant exercise of effort and ingenuity for the grower.[4] By contrast with other plant cultivation practices, bonsai is not intended for production of food or for medicine. Instead, bonsai practice focuses on long-term cultivation and shaping of one or more small trees growing in a container.

A bonsai is created beginning with a specimen of source material. This may be a cutting, seedling, or small tree of a species suitable for bonsai development. Bonsai can be created from nearly any perennial woody-stemmed tree or shrub species[5] that produces true branches and can be cultivated to remain small through pot confinement with crown and root pruning. Some species are popular as bonsai material because they have characteristics, such as small leaves or needles, that make them appropriate for the compact visual scope of bonsai.

The source specimen is shaped to be relatively small and to meet the aesthetic standards of bonsai. When the candidate bonsai nears its planned final size it is planted in a display pot, usually one designed for bonsai display in one of a few accepted shapes and proportions. From that point forward, its growth is restricted by the pot environment. Throughout the year, the bonsai is shaped to limit growth, redistribute foliar vigor to areas requiring further development, and meet the artist's detailed design.

The practice of bonsai is sometimes confused with dwarfing, but dwarfing generally refers to research, discovery, or creation of plants that are permanent, genetic miniatures of existing species. Plant dwarfing often uses selective breeding or genetic engineering to create dwarf cultivars. Bonsai does not require genetically dwarfed trees, but rather depends on growing small trees from regular stock and seeds, via manipulation of its growth environment. Bonsai uses cultivation techniques like pruning, root reduction, potting, defoliation, and grafting to produce small trees that mimic the shape and style of mature, full-size trees.

History

Early versions

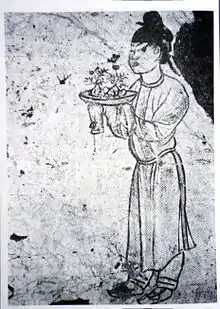

The Japanese art of bonsai originated from the Chinese practice of penjing.[8][9] From the 6th century onward, Imperial embassy personnel and Buddhist students from Japan visited and returned from mainland China. They brought back many Chinese ideas and goods, including container plantings.[10] Over time, these container plantings began to appear in Japanese writings and representative art.

In the medieval period, recognizable bonsai were portrayed in handscroll paintings like the Ippen shonin eden (1299).[11] The 1195 scroll Saigyo Monogatari Emaki was the earliest known to depict dwarfed potted trees in Japan. Wooden tray and dish-like pots with dwarf landscapes on modern-looking wooden shelves also appear in the 1309 Kasuga-gongen-genki scroll. In 1351, dwarf trees displayed on short poles were portrayed in the Boki Ekotoba scroll.[12] Several other scrolls and paintings also included depictions of these kinds of trees.

A close relationship between Japan's Zen Buddhism and the potted trees began to shape bonsai reputation and aesthetics. In this period, Chinese Chan (pronounced "Zen" in Japanese) Buddhist monks taught at Japan's monasteries. One of the monks' activities was to introduce political leaders to various arts of miniature landscapes as admirable accomplishments for men of taste and learning.[13][14] Potted landscape arrangements up to this period included miniature figurines after the Chinese fashion. Japanese artists eventually adopted a simpler style for bonsai, increasing focus on the tree by removing miniatures and other decorations, and using smaller, plainer pots.[15]

Hachi no ki

Around the 14th century, the term for dwarf potted trees was "the bowl's tree" (鉢の木, hachi no ki).[16] This indicated use of a fairly deep pot, rather than the shallow pot denoted by the eventual term bonsai. Hachi no Ki (The Potted Trees) is also the title of a Noh play by Zeami Motokiyo (1363–1444), based on a story in c. 1383 about an impoverished samurai who burns his last three potted trees as firewood to warm a traveling monk. The monk is a disguised official who later rewards the samurai for his actions. In later centuries, woodblock prints by several artists depicted this popular drama. There was even a fabric design of the same name. Through these and other popular media, bonsai became known to a broad Japanese population.

Bonsai cultivation reached a high level of expertise in this period. Bonsai dating to the 17th century have survived to the present. One of the oldest-known living bonsai trees, considered one of the National Treasures of Japan, can be seen in the Tokyo Imperial Palace collection.[17] A five-needle pine (Pinus pentaphylla var. negishi) known as Sandai-Shogun-No Matsu is documented as having been cared for by Tokugawa Iemitsu.[17][18] The tree is thought to be at least 500 years old and was trained as a bonsai by, at latest, the year 1610.[17]

By the end of the 18th century, bonsai cultivation in Japan was becoming widespread and began to interest the general public. In the Tenmei era (1781–88), an exhibit of traditional dwarf potted pines began to be held every year in Kyoto. Connoisseurs from five provinces and neighboring areas would bring one or two plants each to the show in order to submit them to visitors for ranking.[19]

Classical period

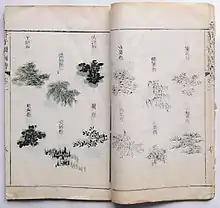

In Japan after 1800, bonsai began to move from being the esoteric practice of a few specialists to becoming a widely popular art form and hobby. In Itami, Hyōgo (near Osaka), Japanese scholars of Chinese arts gathered in the early 19th century to discuss recent styles in the art of miniature trees. Many terms and concepts adopted by this group were derived from the Jieziyuan Huazhuan (Manual of the Mustard Seed Garden in English; Kai-shi-en Gaden in Japanese).[21][22] The Japanese version of potted trees, which had been previously called hachiue or other terms, were renamed bonsai (the Japanese pronunciation of the Chinese term penzai). This word connoted a shallow container, not a deeper bowl style.[23] The term "bonsai", however, would not become broadly used in describing Japan's dwarf potted trees for nearly a century.

The popularity of bonsai began to grow outside the limited scope of scholars and the nobility. On October 13, 1868, the Meiji Emperor moved to his new capital in Tokyo. Bonsai were displayed both inside and outside Meiji Palace, and those placed in the grand setting of the Imperial Palace had to be "Giant Bonsai", large enough to fill the grand space.[24][25][26] The Meiji Emperor encouraged interest in bonsai, which broadened its importance and appeal to his government's professional staff.[27][28]

New books, magazines, and public exhibitions made bonsai more accessible to the Japanese populace. An Artistic Bonsai Concours was held in Tokyo in 1892, followed by publication of a three-volume commemorative picture book. This event demonstrated a new tendency to see bonsai as an independent art form.[29] In 1903, the Tokyo association Jurakukai held showings of bonsai and ikebana at two Japanese-style restaurants. Three years later, Bonsai Gaho (1906 – c. 1913), became the first monthly magazine on the subject.[30] It was followed by Toyo Engei and Hana in 1907.[31] The initial issue of Bonsai magazine was published in 1921 by Norio Kobayashi (1889–1972), and this influential periodical would run for 518 consecutive issues.

Bonsai shaping aesthetics, techniques, and tools became increasingly sophisticated as bonsai's popularity grew in Japan. In 1910, shaping with wire rather than the older string, rope, and burlap techniques, appeared in the Sanyu-en Bonsai-Dan (History of Bonsai in the Sanyu nursery). Zinc-galvanized steel wire was initially used. Expensive copper wire was used only for selected trees that had real potential.[32][33] In the 1920s and 1930s, Toolsmith Masakuni I (1880–1950) helped design and produce the first steel tools specifically made for the developing requirements of bonsai styling.[34] These included the concave cutter, a branch cutter designed to leave a shallow indentation on the trunk when a branch was removed. Properly treated, this indentation would fill over with live tree tissue and bark over time, greatly reducing or eliminating the usual pruning scar.

Prior to World War II, international interest in bonsai was fueled by increased trade in trees and the appearance of books in popular foreign languages. By 1914, the first national annual bonsai show was held (an event repeated annually through 1933) in Tokyo's Hibiya Park.[35][36] Another great annual public exhibition of trees began in 1927 at the Asahi Newspaper Hall in Tokyo.[37] Beginning in 1934, the prestigious Kokufu-ten annual exhibitions were held in Tokyo's Ueno Park.[38] The first major book on the subject in English was published in the Japanese capital: Dwarf Trees (Bonsai) by Shinobu Nozaki (1895–1968).[39]

By 1940, about 300 bonsai dealers worked in Tokyo. Some 150 species of trees were being cultivated, and thousands of specimens annually were shipped to Europe and America. The first bonsai nurseries and clubs in the Americas were started by first and second-generation Japanese immigrants. Though this progress to international markets and enthusiasts was interrupted by the war, bonsai had by the 1940s become an art form of international interest and involvement.

Modern bonsai

%252C_dalla_vcina%252C_circa_100_anni.jpg.webp)

Following World War II, a number of trends made the Japanese tradition of bonsai increasingly accessible to Western and world audiences. One key trend was the increase in the number, scope, and prominence of bonsai exhibitions. For example, the Kokufu-ten bonsai displays reappeared in 1947 after a four-year cancellation and became annual affairs. These displays continue to this day, and are by invitation only for eight days in February.[38] In October 1964, a great exhibition was held in Hibya Park by the private Kokufu Bonsai Association, reorganized into the Nippon Bonsai Association, to mark the Tokyo Olympics.

A large display of bonsai and suiseki was held as part of Expo '70, and formal discussion was made of an international association of enthusiasts. In 1975, the first Gafu-ten (Elegant-Style Exhibit) of shohin bonsai (13–25 cm or 5–10 in tall) was held. So was the first Sakufu-ten (Creative Bonsai Exhibit), the only event in which professional bonsai growers exhibit traditional trees under their own names rather than under the name of the owner.

The First World Bonsai Convention was held in Osaka during the World Bonsai and Suiseki Exhibition in 1980.[40] Nine years later, the first World Bonsai Convention was held in Omiya and the World Bonsai Friendship Federation (WBFF) was inaugurated. These conventions attracted several hundreds of participants from dozens of countries and have since been held every four years at different locations around the globe: 1993, Orlando, Florida; 1997, Seoul, Korea; 2001, Munich, Germany; 2005, Washington, D.C.; 2009, San Juan, Puerto Rico.[40][41] Currently, Japan continues to host regular exhibitions with the world's largest numbers of bonsai specimens and the highest recognized specimen quality.

Another key trend was the increase in books on bonsai and related arts, now being published for the first time in English and other languages for audiences outside Japan. In 1952, Yuji Yoshimura, son of a Japanese bonsai community leader, collaborated with German diplomat and author Alfred Koehn to give bonsai demonstrations. Koehn had been an enthusiast before the war, and his 1937 book Japanese Tray Landscapes had been published in English in Peking. Yoshimura's 1957 book The Art of Bonsai, written in English with his student Giovanna M. Halford, went on to be called the "classic Japanese bonsai bible for westerners" with over thirty printings.[42]

The related art of saikei was introduced to English-speaking audiences in 1963 in Kawamoto and Kurihara's book Bonsai-Saikei. This book described tray landscapes made with younger plant material than was traditionally used in bonsai, providing an alternative to the use of large, older plants, few of which had escaped war damage.

A third trend was the increasing availability of expert bonsai training, at first only in Japan and then more widely. In 1967 the first group of Westerners studied at an Ōmiya nursery. Returning to the U.S., these people established the American Bonsai Society. Other groups and individuals from outside Asia then visited and studied at the various Japanese nurseries, occasionally even apprenticing under the masters. These visitors brought back to their local clubs the latest techniques and styles, which were then further disseminated. Japanese teachers also traveled widely, bringing hands-on bonsai expertise to all six continents[43]

The final trend supporting world involvement in bonsai is the widening availability of specialized bonsai plant stock, soil components, tools, pots, and other accessory items. Bonsai nurseries in Japan advertise and ship specimen bonsai worldwide. Most countries have local nurseries providing plant stock as well. Japanese bonsai soil components, such as Akadama clay, are available worldwide, and suppliers also provide similar local materials in many locations. Specialized bonsai tools are widely available from Japanese and Chinese sources. Potters around the globe provide material to hobbyists and specialists in many countries.[44]

Bonsai has now reached a worldwide audience. There are over twelve hundred books on bonsai and the related arts in at least twenty-six languages available in over ninety countries and territories.[45][46] A few dozen magazines in over thirteen languages are in print. Several score of club newsletters are available on-line, and there are at least that many discussion forums and blogs.[47] There are at least a hundred thousand enthusiasts in some fifteen hundred clubs and associations worldwide, as well as over five million unassociated hobbyists.[48] Plant material from every location is being trained into bonsai and displayed at local, regional, national, and international conventions and exhibitions for enthusiasts and the general public.

Cultivation and care

Bonsai cultivation and care requires techniques and tools that are specialized to support the growth and long-term maintenance of trees in small containers.

Material sources

All bonsai start with a specimen of source material, a plant that the grower wishes to train into bonsai form. Bonsai practice is an unusual form of plant cultivation in that growth from seeds is rarely used to obtain source material. To display the characteristic aged appearance of a bonsai within a reasonable time, the source plant is often mature or at least partially grown when the bonsai creator begins work. Sources of bonsai material include:

- Propagation from a source tree through cuttings or layering.

- Nursery stock directly from a nursery, or from a garden centre or similar resale establishment.

- Commercial bonsai growers, which, in general, sell mature specimens that display bonsai aesthetic qualities already.

- Collecting suitable bonsai material in its original wild situation, successfully moving it, and replanting it in a container for development as bonsai. These trees are called yamadori and are often the most expensive and prized of all Bonsai.

Techniques

The practice of bonsai development incorporates a number of techniques either unique to bonsai or, if used in other forms of cultivation, applied in unusual ways that are particularly suitable to the bonsai domain. These techniques include:

- Leaf trimming, the selective removal of leaves (for most varieties of deciduous tree) or needles (for coniferous trees and some others) from a bonsai's trunk and branches.

- Pruning the trunk, branches, and roots of the candidate tree.

- Wiring branches and trunks allows the bonsai designer to create the desired general form and make detailed branch and leaf placements.

- Clamping using mechanical devices for shaping trunks and branches.

- Grafting new growing material (typically a bud, branch, or root) into a prepared area on the trunk or under the bark of the tree.

- Defoliation, which can provide short-term dwarfing of foliage for certain deciduous species.

- Deadwood bonsai techniques such as jin and shari simulate age and maturity in a bonsai.

Care

Small trees grown in containers, like bonsai, require specialized care. Unlike houseplants and other subjects of container gardening, tree species in the wild, in general, grow roots up to several meters long and root structures encompassing several thousand liters of soil. In contrast, a typical bonsai container is under 25 centimeters in its largest dimension and 2 to 10 liters in volume. Branch and leaf (or needle) growth in trees is also of a larger scale in nature. Wild trees typically grow 5 meters or taller when mature, whereas the largest bonsai rarely exceed 1 meter and most specimens are significantly smaller. These size differences affect maturation, transpiration, nutrition, pest resistance, and many other aspects of tree biology. Maintaining the long-term health of a tree in a container requires some specialized care techniques:

- Watering must be regular and must relate to the bonsai species' requirement for dry, moist, or wet soil.

- Repotting must occur at intervals dictated by the vigor and age of each tree.

- Tools have been developed for the specialized requirements of maintaining bonsai.

- Soil composition and fertilization must be specialized to the needs of each bonsai tree, although bonsai soil is almost always a loose, fast-draining mix of components.[49]

- Location and overwintering are species-dependent when the bonsai is kept outdoors as different species require different light conditions. Few of the traditional bonsai species can survive inside a typical house, due to the usually dry indoor climate.[50]

Aesthetics

%252C_dalla_cina%252C_circa_120_anni.jpg.webp)

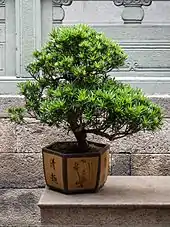

Bonsai aesthetics are the aesthetic goals characterizing the Japanese tradition of growing an artistically shaped miniature tree in a container. Many Japanese cultural characteristics, in particular the influence of Zen Buddhism and the expression of Wabi-sabi,[51] inform the bonsai tradition in Japan. Established art forms that share some aesthetic principles with bonsai include penjing and saikei. A number of other cultures around the globe have adopted the Japanese aesthetic approach to bonsai, and, while some variations have begun to appear, most hew closely to the rules and design philosophies of the Japanese tradition.

Over centuries of practice, the Japanese bonsai aesthetic has encoded some important techniques and design guidelines. Like the aesthetic rules that govern, for example, Western common practice period music, bonsai's guidelines help practitioners work within an established tradition with some assurance of success. Simply following the guidelines alone will not guarantee a successful result. Nevertheless, these design rules can rarely be broken without reducing the impact of the bonsai specimen. Some key principles in bonsai aesthetics include:

- Miniaturization: By definition, a bonsai is a tree kept small enough to be container-grown while otherwise fostered to have a mature appearance.

- Proportion among elements: The most prized proportions mimic those of a full-grown tree as closely as possible. Small trees with large leaves or needles are out of proportion and are avoided, as is a thin trunk with thick branches.

- Asymmetry: Bonsai aesthetics discourage strict radial or bilateral symmetry in branch and root placement.

- No trace of the artist: The designer's touch must not be apparent to the viewer. If a branch is removed in shaping the tree, the scar will be concealed. Likewise, wiring should be removed or at least concealed when the bonsai is shown, and must leave no permanent marks on the branch or bark.[52]

- Poignancy: Many of the formal rules of bonsai help the grower create a tree that expresses Wabi-sabi, or portrays an aspect of mono no aware.

Display

A bonsai display presents one or more bonsai specimens in a way that allows a viewer to see all the important features of the bonsai from the most advantageous position. That position emphasizes the bonsai's defined "front", which is designed into all bonsai. It places the bonsai at a height that allows the viewer to imagine the bonsai as a full-size tree seen from a distance, siting the bonsai neither so low that the viewer appears to be hovering in the sky above it nor so high that the viewer appears to be looking up at the tree from beneath the ground. Noted bonsai writer Peter Adams recommends that bonsai be shown as if "in an art gallery: at the right height; in isolation; against a plain background, devoid of all redundancies such as labels and vulgar little accessories."[53]

For outdoor displays, there are few aesthetic rules. Many outdoor displays are semi-permanent, with the bonsai trees in place for weeks or months at a time. To avoid damaging the trees, therefore, an outdoor display must not impede the amount of sunlight needed for the trees on display, must support watering, and may also have to block excessive wind or precipitation.[54] As a result of these practical constraints, outdoor displays are often rustic in style, with simple wood or stone components. A common design is the bench, sometimes with sections at different heights to suit different sizes of bonsai, along which bonsai are placed in a line. Where space allows, outdoor bonsai specimens are spaced far enough apart that the viewer can concentrate on one at a time. When the trees are too close to each other, aesthetic discord between adjacent trees of different sizes or styles can confuse the viewer, a problem addressed by exhibition displays.

Exhibition displays allow many bonsai to be displayed in a temporary exhibition format, typically indoors, as would be seen in a bonsai design competition. To allow many trees to be located close together, exhibition displays often use a sequence of small alcoves, each containing one pot and its bonsai contents. The walls or dividers between the alcoves make it easier to view only one bonsai at a time. The back of the alcove is a neutral color and pattern to avoid distracting the viewer's eye. The bonsai pot is almost always placed on a formal stand, of a size and design selected to complement the bonsai and its pot.[55]

Indoors, a formal bonsai display is arranged to represent a landscape, and traditionally consists of the featured bonsai tree in an appropriate pot atop a wooden stand, along with a shitakusa (companion plant) representing the foreground, and a hanging scroll representing the background. These three elements are chosen to complement each other and evoke a particular season, and are composed asymmetrically to mimic nature.[56] When displayed inside a traditional Japanese home, a formal bonsai display will often be placed within the home's tokonoma or formal display alcove. An indoor display is usually very temporary, lasting a day or two, as most bonsai are intolerant of indoor conditions and lose vigor rapidly within the house.

Containers

A variety of informal containers may house the bonsai during its development, and even trees that have been formally planted in a bonsai pot may be returned to growing boxes from time to time. A large growing box can house several bonsai and provide a great volume of soil per tree to encourage root growth. A training box will have a single specimen, and a smaller volume of soil that helps condition the bonsai to the eventual size and shape of the formal bonsai container. There are no aesthetic guidelines for these development containers, and they may be of any material, size, and shape that suit the grower.

Completed trees are grown in formal bonsai containers. These containers are usually ceramic pots, which come in a variety of shapes and colors and may be glazed or unglazed. Unlike many common plant containers, bonsai pots have drainage holes in the bottom surface to complement fast-draining bonsai soil, allowing excess water to escape the pot. Growers cover the holes with a screening to prevent soil from falling out and to hinder pests from entering the pots from below. Pots usually have vertical sides, so that the tree's root mass can easily be removed for inspection, pruning, and replanting, although this is a practical consideration and other container shapes are acceptable.

There are alternatives to the conventional ceramic pot. Multi-tree bonsai may be created atop a fairly flat slab of rock, with the soil mounded above the rock surface and the trees planted within the raised soil. In recent times, bonsai creators have also begun to fabricate rock-like slabs from raw materials including concrete[57] and glass-reinforced plastic.[58] Such constructed surfaces can be made much lighter than solid rock, can include depressions or pockets for additional soil, and can be designed for drainage of water, all characteristics difficult to achieve with solid rock slabs. Other unconventional containers can also be used, but in formal bonsai display and competitions in Japan, the ceramic bonsai pot is the most common container.

For bonsai being shown formally in their completed state, pot shape, color, and size are chosen to complement the tree as a picture frame is chosen to complement a painting. In general, containers with straight sides and sharp corners are used for formally shaped plants, while oval or round containers are used for plants with informal designs. Many aesthetic guidelines affect the selection of pot finish and color. For example, evergreen bonsai are often placed in unglazed pots, while deciduous trees usually appear in glazed pots. Pots are also distinguished by their size. The overall design of the bonsai tree, the thickness of its trunk, and its height are considered when determining the size of a suitable pot.

Some pots are highly collectible, like ancient Chinese or Japanese pots made in regions with experienced pot makers such as Tokoname, Japan, or Yixing, China. Today many potters worldwide produce pots for bonsai.[44]

Bonsai styles

%252C_dalla_cina%252C_circa_50_anni.jpg.webp)

The Japanese tradition describes bonsai tree designs using a set of commonly understood, named styles.[59] The most common styles include formal upright, informal upright, slanting, semi-cascade, cascade, raft, literati, and group/forest. Less common forms include windswept, weeping, split-trunk, and driftwood styles.[4][60] These terms are not mutually exclusive, and a single bonsai specimen can exhibit more than one style characteristic. When a bonsai specimen falls into multiple style categories, the common practice is to describe it by the dominant or most striking characteristic.

A frequently used set of styles describes the orientation of the bonsai tree's main trunk. Different terms are used for a tree with its apex directly over the center of the trunk's entry into the soil, slightly to the side of that center, deeply inclined to one side, and inclined below the point at which the trunk of the bonsai enters the soil.[61]

- Formal upright (直幹, chokkan) is a style of trees characterized by a straight, upright, tapering trunk. Branches progress regularly from the thickest and broadest at the bottom to the finest and shortest at the top.[62]

- Informal upright (模様木, moyogi) is a style of trees incorporating visible curves in trunk and branches, but the apex of the informal upright is located directly above the trunk's entry into the soil line.[63]

- Slant (斜幹, shakan) is a style of bonsai possessing straight trunks like those of bonsai grown in the formal upright style. However, the slant style trunk emerges from the soil at an angle, and the apex of the bonsai will be located to the left or right of the root base.[64]

- Cascade (懸崖, kengai) is a style of specimens modeled after trees that grow over water or down the sides of mountains. The apex (tip of the tree) in the semi-cascade (半懸崖, han-kengai) style bonsai extend just at or beneath the lip of the bonsai pot; the apex of a full cascade-style falls below the base of the pot.[65]

A number of styles describe the trunk shape and bark finish. For example, the deadwood bonsai styles identify trees with prominent dead branches or trunk scarring.[66]

- Shari (舎利幹, sharimiki) is a style involving the portrayal of a tree in its struggle to live while a significant part of its trunk is bare of bark.[67]

Although most bonsai trees are planted directly into the soil, there are styles describing trees planted on rock.[68]

- Root-over-rock (石上樹, sekijoju) is a style in which the roots of the tree are wrapped around a rock, entering the soil at the base of the rock.

- Growing-in-a-rock (石付 ishizuke or ishitsuki) is a style in which the roots of the tree are growing in soil contained within the cracks and holes of the rock.

While the majority of bonsai specimens feature a single tree, there are well-established style categories for specimens with multiple trunks.[69]

- Forest or group (寄せ植え, yose ue) is a style comprising the planting of several or many trees of one species, typically an odd number, in a bonsai pot.[70]

- Multi-trunk styles like sokan and sankan have all the trunks growing out of one spot with one root system, so the bonsai is actually a single tree.

- Raft (筏吹き, ikadabuki) is a style of bonsai that mimic a natural phenomenon that occurs when a tree topples onto its side from erosion or another natural force. Branches along the top side of the trunk continue to grow as a group of new trunks.

Other styles

A few styles do not fit into the preceding categories. These include:

- Literati (文人木, bunjin-gi) is a style characterized by a generally bare trunk line, with branches reduced to a minimum, and foliage placed toward the top of a long, often contorted trunk.

- Broom (箒立ち, hokidachi) is a style employed for trees with fine branching, like elms. The trunk is straight and branches out in all directions about 1⁄3 of the way up the entire height of the tree. The branches and leaves form a ball-shaped crown.[71]

- Windswept (吹き流し, fukinagashi) is a style describing a tree that appears to be affected by strong winds blowing continuously from one direction, as might shape a tree atop a mountain ridge or on an exposed shoreline.[72]

Bonsai artists

This is a list of some notable bonsai artists. It is by no means exhaustive.

| Name | Year of birth | Year of death | Nationality |

|---|---|---|---|

| Bjorn Bjorholm | 1986 | American | |

| Marco Invernizzi | 1975 | Italian | |

| Masahiko Kimura | 1940 | Japanese | |

| Kunio Kobayashi | 1948 | Japanese | |

| John Naka | 1914 | 2004 | American |

| Frank Okamura | 1911 | 2006 | Japanese-American |

| Walter Pall | 1944 | Austrian-German | |

| William N. Valavanis | 1951 | Greek-American | |

| Yuji Yoshimura | 1921 | 1997 | Japanese |

Size classifications

Japanese bonsai exhibitions and catalogs frequently refer to the size of individual bonsai specimens by assigning them to size classes (see table below). Not all sources agree on the exact sizes or names for these size ranges, but the concept of the ranges is well-established and useful to both the cultivation and the aesthetic understanding of the trees. A photograph of a bonsai may not give the viewer an accurate impression of the tree's real size, so printed documents may complement a photograph by naming the bonsai's size class. The size class implies the height and weight of the tree in its container.

In the very largest size ranges, a recognized Japanese practice is to name the trees "two-handed", "four-handed", and so on, based on the number of men required to move the tree and pot. These trees will have dozens of branches and can closely simulate a full-size tree. The very largest size, called "imperial", is named after the enormous potted trees of Japan's Imperial Palace.[73]

At the other end of the size spectrum, there are a number of specific techniques and styles associated solely with the smallest common sizes, mame and shito. These techniques take advantage of the bonsai's minute dimensions and compensate for the limited number of branches and leaves that can appear on a tree this small.

| Common names for bonsai size classes[74] | ||

|---|---|---|

| Large bonsai | ||

| Common name | Size class | Tree Height |

| Imperial bonsai | Eight-handed | 152–203 cm (60–80 in) |

| Hachi-uye | Six-handed | 102–152 cm (40–60 in) |

| Dai | Four-handed | 76–122 cm (30–48 in) |

| Omono | Four-handed | 76–122 cm (30–48 in) |

| Medium-size bonsai | ||

| Common name | Size class | Tree Height |

| Chiu | Two-handed | 41–91 cm (16–36 in) |

| Chumono | Two-handed | 41–91 cm (16–36 in) |

| Katade-mochi | One-handed | 25–46 cm (10–18 in) |

| Miniature bonsai | ||

| Common name | Size class | Tree Height |

| Komono | One-handed | 15–25 cm (6–10 in) |

| Shohin | One-handed | 13–20 cm (5–8 in) |

| Mame | Palm size | 5–15 cm (2–6 in) |

| Shito | Fingertip size | 5–10 cm (2–4 in) |

| Keshitsubo | Poppy-seed size | 3–8 cm (1–3 in) |

Indoor bonsai

The Japanese tradition of bonsai does not include indoor bonsai, and bonsai appearing at Japanese exhibitions or in catalogs have been grown outdoors for their entire lives. In less-traditional settings, including climates more severe than Japan's, indoor bonsai may appear in the form of potted trees cultivated for the indoor environment.[75]

Traditionally, bonsai are temperate climate trees grown outdoors in containers.[76] Kept in the artificial environment of a home, these trees weaken and die. However, a number of tropical and sub-tropical tree species will survive and grow indoors.

See also

References

- Gustafson, Herbert L. (1995). Miniature Bonsai. Sterling Publishing Company, Inc. p. 9. ISBN 0-8069-0982-X.

- "Day of the bonsai vegetables". The Independent. Retrieved 2018-08-06.

- "Not All Trees Are Cut Out to Be Bonsai". The New York Times. Retrieved 2018-08-06.

- Chan, Peter (1987). Bonsai Masterclass. Sterling Publishing Co., Inc. ISBN 0-8069-6763-3.

- Owen, Gordon (1990). The Bonsai Identifier. Quintet Publishing Ltd. p. 11. ISBN 0-88665-833-0.

- Taylor, Patrick (2008). The Oxford companion to the garden (2nd ed.). Oxford: Oxford University Press. p. 53. ISBN 978-0-19-955197-2.

The earliest illustration of bonsai was discovered in the Chinese tomb of Prince Zhang Huai, who died in 706.

- Hu, Yunhua (1987). Chinese penjing: Miniature trees and landscapes. Portland: Timber Press. p. 128. ISBN 978-0-88192-083-3.

- Taylor, Patrick (2008). The Oxford companion to the garden (2nd ed.). Oxford: Oxford University Press. p. 53. ISBN 978-0-19-955197-2.

- Keswick, Maggie; Oberlander, Judy; Wai, Joe (1991). In a Chinese Garden: The Art and Architecture of the Dr. Sun Yat-Sen Classical Chinese Garden. Vancouver: Raincoast Book Dist Ltd. p. 59. ISBN 978-0-9694573-0-5.

- Yoshimura, Yuji (1991). "Modern Bonsai, Development Of The Art Of Bonsai From An Historical Perspective, Part 2". International Bonsai (4): 37.

- Kobayashi, Konio (2011). Bonsai. Tokyo: PIE International Inc. p. 15. ISBN 978-4-7562-4094-1.

- "Japanese Paintings: to 1600". Magical Miniature Landscapes. Retrieved 2010-04-07.

- Covello, Vincent T. & Yuji Yoshimura (1984). The Japanese Art of Stone Appreciation, Suiseki and Its Use with Bonsai. Charles E. Tuttle. p. 20.

- Nippon Bonsai Association. Classic Bonsai of Japan. p. 144.

- Redding, Myron. "Art of the Mud Man". Art of Bonsai. Retrieved 2010-04-07.

- "Hachi-No-Ki". Magical Miniature Landscapes. Retrieved 2016-08-10.

- Naka, John Yoshio (1982). Bonsai Techniques II. Bonsai Institute of California. p. 258.

- "Oldest Bonsai trees". Bonsai Empire. Retrieved 2013-11-11.

- Nippon Bonsai Association. Classic Bonsai of Japan. pp. 151–152.

- Warren, Peter (2014). Bonsai. Dorling Kindersley. pp. 10–11. ISBN 978-1-4093-4408-7.

The elite class of monks, scholars, and artists took a slightly different path during the Edo period, [...] One of the biggest influences for the literati artists was the Mustard Seed Garden Manual (Jieziyuan Huazhuan), first published in 1679, which showed how to paint the idealized images. The same images were then recreated in tree form by literati, who were also bonsai enthusiasts.

- Koreshoff. Bonsai: Its Art, Science, History and Philosophy. pp. 7–8.

- Naka, John (1989). "Bunjin-Gi or Bunjin Bonsai". Bonsai in California. 23: 48.

- "Hachi-No-Ki". Magical Miniature Landscapes. Retrieved 2018-07-01.

- Yamada, Tomio (2005). "Fundamentals of Wiring Bonsai". International Bonsai (4): 10–11.

- Hill, Warren (2000). "Reflections on Japan". NBF Bulletin. XI: 5.

- Yamanaka, Kazuki. "The Shimpaku Juniper: Its Secret History, Chapter II. First Shimpaku: Ishizuchi Shimpaku". World Bonsai Friendship Federation. Archived from the original on February 22, 2008. Retrieved 2011-09-29.

- Nozaki. Dwarf Trees ( Bonsai ). p. 24.

- Itoh, Yoshimi (1969). "Bonsai Origins". ABS Bonsai Journal. 3 (1): 3.

- Nippon Bonsai Association. Classic Bonsai of Japan. p. 153.

- "Bonsai and Other Magical Miniature Landscape Specialty Magazines, Part 1". Magical Miniature Landscapes. Retrieved 2016-09-13.

- Kobayashi, Konio (2011). Bonsai. Tokyo: PIE International Inc. p. 16. ISBN 978-4-7562-4094-1.

- "The Books on Bonsai and Related Arts, 1900 - 1949". Magical Miniature Landscapes. Retrieved 2016-09-13.

- Yamada, Tomio (2005). "Fundamentals of Wiring Bonsai". International Bonsai (4): 10.

- "Kyuzo Murata, the Father of Modern Bonsai in Japan, Part 1". Magical Miniature Landscapes. Retrieved 2016-09-16.

- Terry, Thomas Philip, F.R.G.S. (1914). Terry's Japanese Empire. Houghton Mifflin Company. p. 168. Retrieved 2010-04-07.

- Pessy, Christian & Rémy Samson (1992). Bonsai Basics, A Step-by-Step Guide to Growing, Training & General Care. Sterling Publishing Co., Inc. p. 17.

- Koreshoff. Bonsai: Its Art, Science, History and Philosophy. p. 10.

- "Kokufu Bonsai Ten Shows, Part 1". Magical Miniature Landscapes. Retrieved 2016-09-16.

- Nozaki. Dwarf Trees ( Bonsai ). pp. 6, 96.

- "Bonsai Book of Days for April". Magical Miniature Landscapes. Retrieved 2016-09-13.

- "The Conventions, Symposia, Demos, Workshops, and Exhibitions, Part 6". Magical Miniature Landscapes. Retrieved 2016-09-13.

- "Yuji Yoshimura, the Father of Popular Bonsai in the Non-Oriental World". Magical Miniature Landscapes. Retrieved 2016-09-13.

- "Saburō Katō, International Bridge-builder, His Heritage and Legacy, Part 1". Magical Miniature Landscapes. Retrieved 2016-09-13.

- "About Bonsai Pots and Potters". Magical Miniature Landscapes. Retrieved 2016-09-13.

- "The Imperial Bonsai Collection, Part 1". Magical Miniature Landscapes. Retrieved 2016-09-13.

- "The Nations -- When Did Bonsai Come to the Various Countries and Territories?". Magical Miniature Landscapes. Retrieved 2016-09-13.

- "Club Newsletter On-Line". Magical Miniature Landscapes. Retrieved 2016-09-13.

- "How Many Bonsai Enthusiasts Are There?". Magical Miniature Landscapes. Retrieved 2016-09-13.

- "It's All In The Soil by Mike Smith, published in Norfolk Bonsai (Spring 2007) by Norfolk Bonsai Association". Norfolkbonsai.co.uk. Archived from the original on 2007-09-30.

- "Indoor Bonsai Tree". Bonsaidojo.net. December 25, 2013. Archived from the original on December 29, 2015.

- Chan. Bonsai Masterclass. pp. 12–14.

- Chan. Bonsai Masterclass. p. 14.

- Adams, Peter D. (1981). The Art of Bonsai. Ward Lock Ltd. p. 134. ISBN 978-0-8317-0947-1.

- Norman, Ken (2005). Growing Bonsai: A Practical Encyclopedia. Lorenz Books. pp. 176–177. ISBN 978-0-7548-1572-3.

- Adams, Peter D. The Art of Bonsai. Color plates facing pp. 89, 134.

- Andy Rutledge, "Bonsai Display 101", The Art of Bonsai Project. Accessed 18 July 2009.

- Lewis, Colin (2001). The Art of Bonsai Design. Sterling Publishing Company, Inc.: New York. pp. 44–51. ISBN 0-8069-7137-1.

- Adams, Peter D. The Art of Bonsai. Color plates following p. 88; p. 134.

- "Japanese Styles of Bonsai". Magical Miniature Landscapes. Retrieved 2016-09-13.

- D'Cruz, Mark. "Ma-Ke Bonsai Care Guide - Bonsai Styles". Ma-Ke Bonsai. Retrieved 2012-12-24.

- Koreshoff. Bonsai: Its Art, Science, History and Philosophy. p. 153.

- Zane, Thomas L. (2003). "Formal Upright Style Bonsai," Intermediate Bonsai; retrieved 2012-12-20.

- Zane, "Informal Upright Style Bonsai"; retrieved 2012-12-20.

- Zane, "Stanting Style Bonsai"; retrieved 2012-12-20.

- Zane, "Semi-Cascade Style Bonsai"; "Cascade Style Bonsai"; retrieved 2012-12-20.

- Naka, John Yoshio (1973). Bonsai Techniques I. Bonsai Institute of California. pp. 123–124. ISBN 0-930422-31-7.

- "Sharimiki Bonsai". Bonsaiempire.com. Retrieved 2009-11-21.

- Masakuni Kawasumi II; Masakuni Kawasumi III (2005). The Secret Techniques of Bonsai: A guide to starting, raising, and shaping bonsai. Kodansha International. pp. 86–91. ISBN 978-4-7700-2943-0.

- Yuji Yoshimura & Barbara M. Halford (1957). The Art of Bonsai: Creation, Care and Enjoyment. Tuttle Publishing, North Clarendon VT USA. pp. 65–66. ISBN 0-8048-2091-0.

- Zane, "Forest Style Bonsai"; retrieved 2012-12-20.

- Zane, "Broom Style Bonsai"; retrieved 2012-12-20.

- Koreshoff. Bonsai: Its Art, Science, History and Philosophy. pp. 178–185.

- Gustafson. Miniature Bonsai. p. 17.

- Gustafson. Miniature Bonsai. p. 18.

- Lesniewicz, Paul (1996). Bonsai in Your Home. Sterling Publishing Company. ISBN 0-8069-0781-9.

- Indoor Bonsai,online article from the Montreal Botanical Garden

External links

- National Bonsai & Penjing Museum - U.S. National Arboretum, Washington, DC