Politics of Japan

The politics of Japan are conducted in a framework of a multi-party bicameral parliamentary representative democratic constitutional monarchy in which the Emperor is the Head of State and the Prime Minister is the Head of Government and the Head of the Cabinet, which directs the executive branch.

| |

| Polity type | Unitary[1] parliamentary constitutional monarchy[2] |

|---|---|

| Constitution | Constitution of Japan |

| Legislative branch | |

| Name | National Diet |

| Type | Bicameral |

| Meeting place | National Diet Building |

| Upper house | |

| Name | House of Councillors |

| Presiding officer | Akiko Santō, President of the House of Councillors |

| Lower house | |

| Name | House of Representatives |

| Presiding officer | Tadamori Oshima, Speaker of the House of Representatives |

| Executive branch | |

| Head of State | |

| Title | Emperor |

| Currently | Naruhito |

| Appointer | Hereditary |

| Head of Government | |

| Title | Prime Minister |

| Currently | Yoshihide Suga |

| Appointer | Emperor (Nominated by National Diet) |

| Cabinet | |

| Name | Cabinet of Japan |

| Current cabinet | Fourth Abe Cabinet (reshuffle) |

| Leader | Prime Minister |

| Appointer | Prime Minister |

| Headquarters | Sōri Daijin Kantei |

| Judicial branch | |

| Name | Judiciary |

| Supreme Court | |

| Chief judge | Naoto Ōtani |

| Seat | Supreme Court Building |

|

|---|

| This article is part of a series on the politics and government of Japan |

|

|

Legislative power is vested in the National Diet, which consists of the House of Representatives and the House of Councillors. The House of Representatives consists of eighteen standing committees ranging in size from 20 to 50 members and The House of Councillors has sixteen ranging from ten to 45 members. [3]

Judicial power is vested in the Supreme Court and lower courts, and sovereignty is vested in the Japanese people by the Constitution. Japan is considered a constitutional monarchy with a system of civil law.

The Economist Intelligence Unit rated Japan a "flawed democracy" in 2019.[4]

Constitution

Promulgated on November 3, 1946 and coming into effect on May 3, 1947, following the Japanese Empire's defeat to the allies in WW2, Japan’s constitution, as one might expect, is perhaps one of the most unique, in terms of its creation and ratification at least, in the world.

The creation and ratification of this document has been widely viewed as forced upon Japan by the United States. Although this “imposition” claim arose originally as a rallying cry among conservative politicians in favour of constitutional revision in the 1950s, it has also been supported by the research of several American and Japanese historians of the period. A competing claim, which also emerged from the political maelstrom of the 1950s revision debate and has been supported by more recent scholarship, holds that the ratification decision was the result of “collaboration” between U.S. Occupation authorities, successive Japanese governments of the time, and private sector actors.[5]

Regardless of whether either claim is correct, it is undeniable that, with its codification mostly by American authors, the Japanese Constitution takes many of its previous occupier’s values, as is demonstrated by its institutions bearing many similarities to western democracies and in the rights enshrined in it reflecting concepts of liberty.

That is not to say however that this constitution, despite indeed not being brought about by the people, was not supported by them. In fact, the constitution was a largely popular concept to the post-war Japanese public, even if that was somewhat down to relief, a belief that the U.S would save the nation from its economic ruin and a culture of submissiveness to authority. The Constitution does of course offer one of the most extensive catalogues of rights in the world. Another unique aspect of its constitution is that it has not been formerly amended since its ratification. That is not to say there has been no changes regarding it, however. The Constitution, specifically Article 9, has been readjusted, largely by former Prime Minister Shigeru Yoshida, with the addition of extra-constitutional laws and subsequently reinterpreted by Shinzo Abe since then, with the reinterpretation of self-defence as meaning it can respond to perceived threats almost anywhere on the globe.

Government

The Constitution of Japan defines the Emperor[6] to be "the symbol of the State and of the unity of the people". He performs ceremonial duties and holds no real power. Political power is held mainly by the Prime Minister and other elected members of the Diet. The Imperial Throne is succeeded by a member of the Imperial House as designated by the Imperial Household Law.

The chief of the executive branch, the Prime Minister, is appointed by the Emperor as directed by the Diet. They are a member of either house of the Diet and must be a civilian. The Cabinet members are nominated by the Prime Minister, and are also required to be civilian. With the Liberal Democratic Party (LDP) in power, it has been convention that the President of the party serves as the Prime Minister.

Legislature

Japan’s constitution states that the National Diet, it’s law-making institution, shall consist of two Houses, namely the House of Representatives and the House of Councillors. The Diet shall be the highest organ of state power, and shall be the sole law-making organ of the State. It states that both Houses shall consist of elected members, representative of all the people and that the number of the members of each House shall be fixed by law. Both houses pass legislation in identical form for it to become law. Similarly to other parliamentary systems, most legislation that is considered in the Diet is proposed by the cabinet. The cabinet then relies on the expertise of the bureaucracy to draft actual bills.

The lower house, the House of Representatives, the most powerful of the two, holds power over the government, being able to force its resignation. The lower house also has ultimate control of the passage of the budget, the ratification of treaties, and the selection of the Prime Minister. Its power over its sister house is, if a bill is passed by the lower house (the House of Representatives) but is voted down by the upper house (the House of Councillors) the ability to override the decision of the House of Councillors. Members of the lower house, as a result of the Prime Minister's power to dissolve them, more frequently serve for less than four years in any given terms.

The upper house, the House of Councillors is very weak and bills are sent to the House of Councillors only to be approved, not made. Members of the upper house are elected for six-year terms with half the members elected every three years.

Its possible for different parties to control the lower house and the super house, a situation referred to as a “twisted Diet”, something that has become more common since the JSP took control of the upper house in 1989.

Political parties and elections

Several political parties exist in Japan. However, the politics of Japan have primarily been dominated by the LDP since 1955, with the DPJ playing an important role as opposition several times. LDP was the ruling party for decades since 1955. Despite the existence of multiple parties, other parties were completely ignored. Most of the prime ministers were elected from inner factions of the LDP.

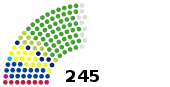

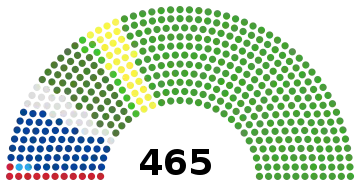

| ↓ | |||||||

| 88 | 16 | 28 | 113 | ||||

| Opposition and independents | Ishin | Kōmeitō | Liberal Democratic | ||||

| |||||||||||||||||||

| Parties | Constituencies | Proportional | Seats | ||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Votes | % | Seats | Votes | % | Seats | Total before |

Not up | Won | Total after |

+/- | |||||||||

| Liberal Democratic Party | 20,330,963 | 39.77 | 38 | 17,711,862 | 35.37 | 19 | 125 | 56 | 57 | 113 | |||||||||

| Constitutional Democratic Party | 7,951,430 | 15.79 | 9 | 7,917,719 | 15.81 | 8 | 28 | 15 | 17 | 32 | |||||||||

| Komeito | 3,913,359 | 7.77 | 7 | 6,536,336 | 13.05 | 7 | 25 | 14 | 14 | 28 | |||||||||

| Nippon Ishin no Kai | 3,664,530 | 7.28 | 5 | 4,907,844 | 9.80 | 5 | 11 | 6 | 10 | 16 | |||||||||

| Communist Party | 3,710,768 | 7.37 | 3 | 4,483,411 | 8.95 | 4 | 14 | 6 | 7 | 13 | |||||||||

| Democratic Party for the People | 3,256,859 | 6.47 | 3 | 3,481,053 | 6.95 | 3 | 27 | 15 | 6 | 21 | New | ||||||||

| Reiwa Shinsengumi | 214,438 | 0.43 | 0 | 2,280,764 | 4.55 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 2 | New | ||||||||

| Social Democratic Party | 191,820 | 0.38 | 0 | 1,046,011 | 2.09 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 2 | |||||||||

| Party to Protect the People from NHK | 1,521,344 | 3.02 | 0 | 987,885 | 1.97 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | New | ||||||||

| Others (5 parties) | 573,250 | 1.14 | 0 | 719,282 | 1.44 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | - | ||||||||

| Independents | 5,335,641 | 10.59 | 9 | 10 | 8 | 9 | 17 | ||||||||||||

| Valid votes | 50,363,771 | - | 50,072,199 | ||||||||||||||||

| Blank and invalid votes | 1,308,151 | - | 1,394,498 | ||||||||||||||||

| Total | 51,671,922 | 100 | 74 | 51,666,697 | 100 | 50 | 242 | 121 | 124 | 245 | +3 | ||||||||

| Registered voters / turnout | 105,886,064 | 48.80 | - | 105,886,064 | 48.79 | ||||||||||||||

| Source : Results | |||||||||||||||||||

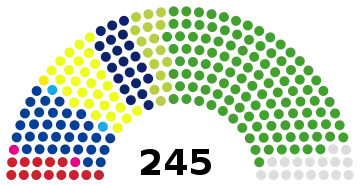

| ||||||||||||||

| Parties | Constituency | PR Block | Total seats | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Votes | % | ±pp | Seats | Votes | % | ±pp | Seats | Seats | ± | % | ±pp | |||

| Liberal Democratic Party (LDP) | 26,719,032 | 48.21 | 218 | 18,555,717 | 33.28 | 66 | 284 | 61.08 | ||||||

| Komeitō (NKP) | 832,453 | 1.50 | 8 | 6,977,712 | 12.51 | 21 | 29 | 6.24 | ||||||

| Governing coalition | 27,551,485 | 49.71 | 226 | 25,533,429 | 45.79 | 87 | 313 | 67.31 | ||||||

| Constitutional Democratic Party of Japan (CDP) | 4,852,097 | 8.75 | New | 18 | 11,084,890 | 19.88 | New | 37 | 55 | 11.83 | ||||

| Japanese Communist Party (JCP) | 4,998,932 | 9.02 | 1 | 4,404,081 | 7.90 | 11 | 12 | 2.58 | ||||||

| Social Democratic Party (SDP) | 634,719 | 1.15 | 1 | 941,324 | 1.69 | 1 | 2 | 0.43 | ||||||

| Liberalist coalition | 10,485,748 | 18.92 | – | 20 | 16,430,295 | 29.47 | – | 49 | 69 | 14.84 | ||||

| Kibō no Tō (Party of Hope) | 11,437,601 | 20.64 | New | 18 | 9,677,524 | 17.36 | New | 32 | 50 | 10.75 | ||||

| Nippon Ishin no Kai (JIP) | 1,765,053 | 3.18 | 3 | 3,387,097 | 6.07 | 8 | 11 | 2.37 | ||||||

| The third coalition | 13,202,654 | 23.82 | – | 21 | 13,064,621 | 23.43 | – | 40 | 61 | 13.12 | ||||

| Happiness Realization Party (HRP) | 159,171 | 0.29 | – | 0 | 292,084 | 0.52 | 0 | 0 | 0.00 | |||||

| New Party Daichi | – | – | – | – | 226,552 | 0.41 | – | 0 | 0 | 0.00 | ||||

| No Party to Support | – | – | – | – | 125,019 | 0.22 | 0 | 0 | 0.00 | |||||

| Party for Japanese Kokoro (PJK) | – | – | – | – | 85,552 | 0.15 | 0 | 0 | 0.00 | |||||

| Others | 52,080 | 0.03 | – | 0 | – | – | – | – | 0 | 0.00 | ||||

| Independents | 3,970,946 | 7.16 | 22 | – | – | – | – | 22 | 4.73 | |||||

| Total | 55,422,087 | 100.00 | – | 289 | 55,757,552 | 100.00 | – | 176 | 465 | 100.00 | – | |||

Seats, of total, by party

Policy making

Despite an increasingly unpredictable domestic and international environment, policy making conforms to well established postwar patterns. The close collaboration of the ruling party, the elite bureaucracy and important interest groups often make it difficult to tell who exactly is responsible for specific policy decisions.

Policy development in Japan

After a largely informal process within elite circles in which ideas were discussed and developed, steps might be taken to institute more formal policy development. This process often took place in deliberation councils (shingikai). There were about 200 shingikai, each attached to a ministry; their members were both officials and prominent private individuals in business, education, and other fields. The shingikai played a large role in facilitating communication among those who ordinarily might not meet.

Given the tendency for real negotiations in Japan to be conducted privately (in the nemawashi, or root binding, process of consensus building), the shingikai often represented a fairly advanced stage in policy formulation in which relatively minor differences could be thrashed out and the resulting decisions couched in language acceptable to all. These bodies were legally established but had no authority to oblige governments to adopt their recommendations. The most important deliberation council during the 1980s was the Provisional Commission for Administrative Reform, established in March 1981 by Prime Minister Suzuki Zenko. The commission had nine members, assisted in their deliberations by six advisers, twenty-one "expert members," and around fifty "councillors" representing a wide range of groups. Its head, Keidanren president Doko Toshio, insisted that the government agree to take its recommendations seriously and commit itself to reforming the administrative structure and the tax system.

In 1982, the commission had arrived at several recommendations that by the end of the decade had been actualized. These implementations included tax reform, a policy to limit government growth, the establishment in 1984 of the Management and Coordination Agency to replace the Administrative Management Agency in the Office of the Prime Minister, and privatization of the state-owned railroad and telephone systems. In April 1990, another deliberation council, the Election Systems Research Council, submitted proposals that included the establishment of single-seat constituencies in place of the multiple-seat system.

Another significant policy-making institution in the early 1990s were the Liberal Democratic Party's Policy Research Council. It consisted of a number of committees, composed of LDP Diet members, with the committees corresponding to the different executive agencies. Committee members worked closely with their official counterparts, advancing the requests of their constituents, in one of the most effective means through which interest groups could state their case to the bureaucracy through the channel of the ruling party. See also: Industrial policy of Japan; Monetary and fiscal policy of Japan; Mass media and politics in Japan

Post-war political developments in Japan

Political parties had begun to revive almost immediately after the occupation began. Left-wing organizations, such as the Japan Socialist Party and the Japanese Communist Party, quickly reestablished themselves, as did various conservative parties. The old Rikken Seiyūkai and Rikken Minseitō came back as, the Liberal Party (Nihon Jiyūtō) and the Japan Progressive Party (Nihon Shimpotō) respectively. The first postwar elections were held in 1948 (women were given the franchise for the first time in 1947), and the Liberal Party's vice president, Yoshida Shigeru (1878–1967), became prime minister.

For the 1947 elections, anti-Yoshida forces left the Liberal Party and joined forces with the Progressive Party to establish the new Democratic Party (Minshutō). This divisiveness in conservative ranks gave a plurality to the Japan Socialist Party, which was allowed to form a cabinet, which lasted less than a year. Thereafter, the socialist party steadily declined in its electoral successes. After a short period of Democratic Party administration, Yoshida returned in late 1948 and continued to serve as prime minister until 1954.

Even before Japan regained full sovereignty, the government had rehabilitated nearly 80,000 people who had been purged, many of whom returned to their former political and government positions. A debate over limitations on military spending and the sovereignty of the Emperor ensued, contributing to the great reduction in the Liberal Party's majority in the first post-occupation elections (October 1952). After several reorganizations of the armed forces, in 1954 the Japan Self-Defense Forces were established under a civilian director. Cold War realities and the hot war in nearby Korea also contributed significantly to the United States-influenced economic redevelopment, the suppression of communism, and the discouragement of organized labor in Japan during this period.

Continual fragmentation of parties and a succession of minority governments led conservative forces to merge the Liberal Party (Jiyūtō) with the Japan Democratic Party (Nihon Minshutō), an offshoot of the earlier Democratic Party, to form the Liberal Democratic Party (Jiyū-Minshutō; LDP) in November 1955, called 1955 System. This party continuously held power from 1955 through 1993, except for a short while when it was replaced by a new minority government. LDP leadership was drawn from the elite who had seen Japan through the defeat and occupation. It attracted former bureaucrats, local politicians, businessmen, journalists, other professionals, farmers, and university graduates.

In October 1955, socialist groups reunited under the Japan Socialist Party, which emerged as the second most powerful political force. It was followed closely in popularity by the Kōmeitō, founded in 1964 as the political arm of the Soka Gakkai (Value Creation Society), until 1991, a lay organization affiliated with the Nichiren Shoshu Buddhist sect. The Komeito emphasized the traditional Japanese beliefs and attracted urban laborers, former rural residents, and women. Like the Japan Socialist Party, it favored the gradual modification and dissolution of the Japan-United States Mutual Security Assistance Pact.

Political developments since 1990

The LDP domination lasted until the Diet Lower House elections on 18 July 1993, in which LDP failed to win a majority. A coalition of new parties and existing opposition parties formed a governing majority and elected a new prime minister, Morihiro Hosokawa, in August 1993. His government's major legislative objective was political reform, consisting of a package of new political financing restrictions and major changes in the electoral system. The coalition succeeded in passing landmark political reform legislation in January 1994.

In April 1994, Prime Minister Hosokawa resigned. Prime Minister Tsutomu Hata formed the successor coalition government, Japan's first minority government in almost 40 years. Prime Minister Hata resigned less than two months later. Prime Minister Tomiichi Murayama formed the next government in June 1994 with the coalition of Japan Socialist Party (JSP), the LDP, and the small New Party Sakigake. The advent of a coalition containing the JSP and LDP shocked many observers because of their previously fierce rivalry.

Prime Minister Murayama served from June 1994 to January 1996. He was succeeded by Prime Minister Ryutaro Hashimoto, who served from January 1996 to July 1998. Prime Minister Hashimoto headed a loose coalition of three parties until the July 1998 Upper House election, when the two smaller parties cut ties with the LDP. Hashimoto resigned due to a poor electoral performance by the LDP in the Upper House elections. He was succeeded as party president of the LDP and prime minister by Keizo Obuchi, who took office on 30 July 1998. The LDP formed a governing coalition with the Liberal Party in January 1999, and Keizo Obuchi remained prime minister. The LDP-Liberal coalition expanded to include the New Komeito Party in October 1999.

Political developments since 2000

Prime Minister Obuchi suffered a stroke in April 2000 and was replaced by Yoshirō Mori. After the Liberal Party left the coalition in April 2000, Prime Minister Mori welcomed a Liberal Party splinter group, the New Conservative Party, into the ruling coalition. The three-party coalition made up of the LDP, New Komeito, and the New Conservative Party maintained its majority in the Diet following the June 2000 Lower House elections.

After a turbulent year in office in which he saw his approval ratings plummet to the single digits, Prime Minister Mori agreed to hold early elections for the LDP presidency in order to improve his party's chances in crucial July 2001 Upper House elections. On 24 April 2001, riding a wave of grassroots desire for change, maverick politician Junichiro Koizumi defeated former Prime Minister Hashimoto and other party stalwarts on a platform of economic and political reform.

Koizumi was elected as Japan's 56th Prime Minister on 26 April 2001. On 11 October 2003, Prime Minister Koizumi dissolved the lower house and he was re-elected as the president of the LDP. Likewise, that year, the LDP won the election, even though it suffered setbacks from the new opposition party, the liberal and social-democratic Democratic Party (DPJ). A similar event occurred during the 2004 Upper House elections as well.

In a strong move, on 8 August 2005, Prime Minister Junichiro Koizumi called for a snap election to the lower house, as threatened, after LDP stalwarts and opposition DPJ parliamentarians defeated his proposal for a large-scale reform and privatization of Japan Post, which besides being Japan's state-owned postal monopoly is arguably the world's largest financial institution, with nearly 331 trillion yen of assets. The election was scheduled for 11 September 2005, with the LDP achieving a landslide victory under Junichiro Koizumi's leadership.

The ruling LDP started losing hold since 2006. No prime minister except Koizumi had good public support. On 26 September 2006, new LDP President Shinzō Abe was elected by a special session of the Diet to succeed Junichiro Koizumi as Prime Minister. He was Japan's youngest post-World War II prime minister and the first born after the war. On 12 September 2007, Abe surprised Japan by announcing his resignation from office. He was replaced by Yasuo Fukuda, a veteran of LDP.

In the meantime, on 4 November 2007, leader of the main opposition party, Ichirō Ozawa announced his resignation from the post of party president, after controversy over an offer to the DPJ to join the ruling coalition in a grand coalition,[7] but has since, with some embarrassment, rescinded his resignation.

On 11 January 2008, Prime Minister Yasuo Fukuda forced a bill allowing ships to continue a refueling mission in the Indian Ocean in support of US-led operations in Afghanistan. To do so, PM Fukuda used the LDP's overwhelming majority in the Lower House to ignore a previous "no-vote" of the opposition-controlled Upper House. This was the first time in 50 years that the Lower House voted to ignore the opinion of the Upper House. Fukuda resigned suddenly on 1 September 2008, just a few weeks after reshuffling his cabinet. On 1 September 2008, Fukuda's resignation was designed so that the LDP did not suffer a "power vacuum". It thus caused a leadership election within the LDP, and the winner, Tarō Asō was chosen as the new party president and on 24 September 2008, he was appointed as 92nd Prime Minister after the House of Representatives voted in his favor in the extraordinary session of Diet.[8]

Later, on 21 July 2009, Prime Minister Asō dissolved the House of Representatives and elections were held on 30 August.[9] The election results for the House of Representatives were announced on 30 and 31 August 2009. The opposition party DPJ led by Yukio Hatoyama, won a majority by gaining 308 seats (10 seats were won by its allies the Social Democratic Party and the People's New Party). On 16 September 2009, president of DPJ, Hatoyama was elected by the House of Representatives as the 93rd Prime Minister of Japan.

Political developments since 2010

On 2 June 2010, Hatoyama resigned due to lack of fulfillments of his policies, both domestically and internationally[10] and soon after, on 8 June, Akihito, Emperor of Japan ceremonially swore in the newly elected DPJ's president, Naoto Kan as prime minister.[11] Kan suffered an early setback in the 2010 Japanese House of Councillors election. In a routine political change in Japan, DPJ’s new president and former finance minister of Naoto Kan’s cabinet, Yoshihiko Noda was cleared and elected by the Diet as 95th prime minister on 30 August 2011. He was officially appointed as prime minister in the attestation ceremony at imperial palace on 2 September 2011.[12]

In an undesired move, Noda dissolved the lower house on 16 November 2012 (as he failed to get support outside the Diet on various domestic issues i.e. tax, nuclear energy) and elections were held on 16 December. The results were in favor of the LDP, which won an absolute majority in the leadership of former Prime Minister Shinzō Abe.[13] He was appointed as the 96th Prime Minister of Japan on 26 December 2012.[14] With the changing political situation, earlier in November 2014, Prime Minister Abe called for a fresh mandate for the Lower House. In an opinion poll the government failed to win public trust due to bad economic achievements in the two consecutive quarters and on the tax reforms.[15]

The election was held on 14 December 2014, and the results were in favor of the LDP and its ally New Komeito. Together they managed to secure a huge majority by winning 325 seats for the Lower House. The opposition, DPJ, could not manage to provide the alternatives to the voters with its policies and programs. "Abenomics", the ambitious self-titled fiscal policy of the current prime minister, managed to attract more voters in this election, many Japanese voters supported the policies. Shinzō Abe was sworn as the 97th prime minister on 24 December 2014 and would go ahead with his agenda of economic revitalization and structural reforms in Japan.[15]

Prime Minister Abe was elected again for a fourth term after the 2017 election.[16]

On 28 August 2020 following reports of ill-health, Abe resigned citing health concerns, triggering a leadership election to replace him as Prime Minister.[17]

Foreign relations

Japan is a member state of the United Nations and pursues a permanent membership of the Security Council - Japan is one of the "G4 nations" seeking permanent membership. Japan plays an important role in East Asia. The Japanese Constitution prohibits the use of military forces to wage war against other countries. The government maintains a "Self-Defense Force", which include air, land and sea components. Japan's deployment of non-combat troops to Iraq marked the first overseas use of its military since World War II.

As an economic power, Japan is a member of the G7 and Asia-Pacific Economic Cooperation (APEC), and has developed relations with ASEAN as a member of "ASEAN plus three" and the East Asia Summit. Japan is a major donor in international aid and development efforts, donating 0.19% of its Gross National Income in 2004.[18]

Japan has territorial disputes with Russia over the Kuril Islands (Northern Territories), with South Korea over Liancourt Rocks (known as "Dokdo" in Korea, "Takeshima" in Japan), with China and Taiwan over the Senkaku Islands and with China over the status of Okinotorishima. These disputes are in part about the control of marine and natural resources, such as possible reserves of crude oil and natural gas. Japan has an ongoing dispute with North Korea over its abduction of Japanese citizens and nuclear weapons program.

References

This article incorporates public domain material from the Library of Congress Country Studies website http://lcweb2.loc.gov/frd/cs/. - Japan

This article incorporates public domain material from the Library of Congress Country Studies website http://lcweb2.loc.gov/frd/cs/. - Japan

- Heslop, D. Alan. "Political system - National political systems". britannica.com. Encyclopædia Britannica, Inc. Retrieved 11 June 2020.

- "Japan — The World Factbook". Cia.gov. Central Intelligence Agency. Retrieved 11 June 2020.

- Philip Laundy - Parliaments In The Modern World page 109

- The Economist Intelligence Unit (8 January 2019). "Democracy Index 2019". Economist Intelligence Unit. Retrieved 13 January 2019.

- https://core.ac.uk/download/pdf/144455106.pdf

- Professor Yasuhiro Okudaira notes a misnomer in the use of the word "Emperor" to describe the nation's living state symbol. In Okudaira's view, the word "Emperor" ceased to be applicable when Japan ceased to be an empire under the 1947 Constitution. "Thus, for example, Imperial University of Tokyo became merely University of Tokyo" after World War II. He would apparently have the word tennō directly taken for English use (just as there is no common English word for "sushi". Yasuhiro Okudaira, "Forty Years of the Constitution and its Various Influences: Japanese, American, and European" in Luney and Takahashi, Japanese Constitutional Law (Univ. Tokyo Press, 1993), pp. 1–38, at 4.

- "DPJ leader Ozawa hands in resignation over grand coalition controversy – Japan News Review". japannewsreview.com. Archived from the original on 9 November 2007. Retrieved 17 March 2018.

- The Japan Times http://search.japantimes.co.jp/cgi-bin/nn20080924x1.html. Retrieved 17 March 2018. Missing or empty

|title=(help) - "Critical election to come - The Japan Times". japantimes.co.jp. Retrieved 17 March 2018.

- Archived 5 June 2010 at the Wayback Machine

- "Japan's new PM Naoto Kan names cabinet". 8 June 2010. Retrieved 17 March 2018 – via www.telegraph.co.uk.

- The Japan Times http://search.japantimes.co.jp/cgi-bin/nn20110902x1.html. Retrieved 17 March 2018. Missing or empty

|title=(help) - http://www3.nhk.or.jp/daily/english/20121216_39.html%5B%5D

- http://www.japantimes.co.jp/text/nn20121226x1.html

- "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 24 December 2014. Retrieved 24 December 2014.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- "Shinzo Abe gains big victory in Japan election". Financial Times. 22 October 2017.

- "Shinzo Abe: Japan's PM resigns for health reasons". BBC News. 28 August 2020.

- "Net Official Development Assistance In 2004" (PDF). (32.9 KiB), Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development, 11 April 2005. Retrieved 14 May 2006.

Further reading

- Curtis, Gerald (1999). The Logic of Japanese Politics: Leaders, Institutions, and the Limits of Change. New York: Columbia University Press.

- Hattori, Ryuji (2019). Understanding History in Asia: What Diplomatic Documents Reveal. Tokyo: Japan Publishing Industry Foundation for Culture.

- Hosoya, Yuichi (2019). Security Politics in Japan: Legislation for a New Security Environment. Tokyo: Japan Publishing Industry Foundation for Culture.

- Iokibe, Makoto (2017). The History of US-Japan Relations: From Perry to the Present. New York: Palgrave Macmillan. Archived from the original on 3 June 2019. Retrieved 3 June 2019.

- Kimura, Kan (2019). The Burden of the Past: Problems of Historical Perception in Japan-Korea Relations. Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press. Archived from the original on 27 May 2019. Retrieved 27 May 2019.

- Kitaoka, Shinichi (2018). The Political History of Modern Japan: Foreign Relations and Domestic Politics. Abingdon: Routledge.

- Miyagi, Taizo (2017). Japan's Quest for Stability in Southeast Asia: Navigating the Turning Points in Postwar Asia. Abingdon: Routledge.

- Neary, Ian (2019). The State and Politics In Japan, 2nd Edition. Cambridge: Polity.

- Oros, Andrew (2017). Japan's Security Renaissance: New Policies and Politics for the Twenty-First Century. New York: Columbia University Press.

- Sakai, Hidekazu and Sato Yoichiro (2017). Re-rising Japan: Its Strategic Power in International Relations. Bern: Peter Lang. Archived from the original on 27 May 2019. Retrieved 27 May 2019.

- Serita, Kentaro (2018). The Territory of Japan: Its History and Legal Basis. Tokyo: Japan Publishing Industry Foundation for Culture.

- Smith, Sheila (2019). Japan Rearmed: The Politics of Military Power. Boston: Harvard University Press. Archived from the original on 8 June 2019. Retrieved 27 May 2019.

- Tanaka, Akihiko (2017). Japan in Asia: Post-Cold-War Diplomacy. Tokyo: Japan Publishing Industry Foundation for Culture.

- The Yomiuri Shimbun Political News Department (2017). Perspectives on Sino-Japanese Diplomatic Relations. Tokyo: Japan Publishing Industry Foundation for Culture.