Boundary Channel

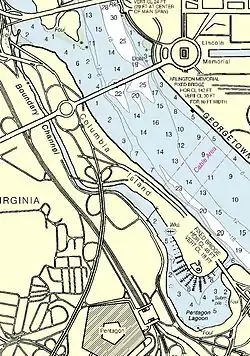

Boundary Channel is a channel off the Potomac River in Washington, D.C. The channel begins at the northwestern tip of Columbia Island extends southward between Columbia Island and the Virginia shoreline. It curves around the southern tip of Columbia Island before heading northeast to exit into the Potomac River. At the southwestern tip of Columbia Island, the Boundary Channel widens into the manmade Pentagon Lagoon.

| Boundary Channel | |

|---|---|

Map of area surrounding Boundary Channel and the Pentagon Lagoon | |

| Location | |

| Country | United States |

| State | District of Columbia |

| Physical characteristics | |

| Source | Potomac River |

| • coordinates | 38°53′24.4″N 77°3′49.3″W |

| • elevation | 0 ft (0 m) |

| Mouth | Pentagon Lagoon |

• coordinates | 38°52′26″N 77°2′53″W |

• elevation | 0 ft (0 m) |

| Basin features | |

| River system | Potomac River |

History of Boundary Channel

Columbia Island is in part natural, and in part man-made. About 1818, Analostan Island (now known as Theodore Roosevelt Island) was largely rock and quite close to the D.C. shoreline. Due to deforestation and increased agricultural use upstream, the river eroded much of the northern bank of the Potomac River and widened the gap between Analostan Island and the shore. Simultaneously, large deposits of silt built up around Analostan Island. By 1838, Analostan had almost doubled in length toward the south. By 1884, the new southern part of Analostan Island was defined and built up, and supported a well-established wetland. Gradually, however, the river eroded the center of Analostan Island, severing Columbia Island from its parent body.[1]

Between 1911 and 1922, the Potomac River was repeatedly dredged by the United States Army Corps of Engineers to deepen the channel and alleviate flooding. Dredging widened the distance between Analostan/Theodore Roosevelt Island and Columbia Island (so that the "Virginia Channel" west of Analostan/Roosevelt Island would not flood easily). Dredged material was piled high on Columbia Island, helping to build it higher, lengthen and broaden it, and give it its current shape.[1] The new island received its name about 1918 from an unnamed engineer working for the District of Columbia.[2]

An anonymous Corps of Engineers officer named the waterway between Columbia Island and Virginia the "Boundary Channel".[3]

Boundary Channel was further defined in the late 1920s. In 1925, Congress authorized construction of the Arlington Memorial Bridge across the Potomac River. Preliminary designs for the bridge showed it terminating on Columbia Island,[4] which necessitated additional expansion of the island. The Corps of Engineers had already planned to continue dredging the Potomac River and enlarge Columbia Island, so on April 1, 1925, Secretary of War John W. Weeks ordered the expenditure of $114,500 to dredge the river between the Highway Bridge and the Lincoln Memorial. The dredged material was dumped on Columbia Island.[5] By June 30, 1927, dredging of the Potomac River and the reshaping of Columbia Island was largely finished.[6]

Boundary Channel marks the original Virginia shoreline.[7] It separates Columbia Island to the east from Virginia in the west and south, and is roughly a mile long. The channel is part of the Potomac River.[8] In 1936, Boundary Channel was 100 to 200 feet (30 to 61 m) in width and 4 to 6 feet (1.2 to 1.8 m) in depth.[9] No lagoon existed at this time.

Broundary Channel was changed again after ground was broken for The Pentagon on September 11, 1941. The Pentagon was being built on land just south of the Boundary Channel. But the ground to the northwest, north, northeast, and east of the building site was so low that, for a time, the Corps of Engineers considered building a levee to protect it from floods. But General Brehon B. Somervell, the Army officer in charge of the Pentagon's construction, decided instead to raise the ground by at least 8 feet (2.4 m) to 18 feet (5.5 m) or more above the average water level. Boundary Channel was dredged and slightly widened in order to help provide this fill material.[10]

Due to silting and other issues, Boundary Channel is approximately 100 feet (30 m) wide as of 2013 (although the width varies). It is also quite shallow.[11]

Pentagon Lagoon

Pentagon Lagoon is a shallow pool which is part of the Boundary Channel.[12] It was originally constructed as part of the channel, and was originally quite small as well as unnamed.[10]

During construction of the Pentagon in 1941, the U.S. Army not only needed a source of fill material to raise the land around the Pentagon, but also needed a way for river barges to deliver concrete, gravel, and sand to the construction site. With unused Columbia Island nearby, the Corps of Engineers quickly removed a portion of the island as well as dredged the bottom of the lagoon for this fill material. The Army also constructed a dike inland on the Virginia shoreline. The earth behind this dike was excavated to a depth 14 feet (4.3 m) below the Potomac River's average high tide. On what was to be the new shoreline, the Army and its contractors built cement plants and marshalling areas for the deposit of sand and gravel. The dike was then breached (and removed by dredge), allowing barges and other ships to deliver construction materials quickly and cheaply to the building site. More than 1,000,000 cubic yards (760,000 m3) of earth and riverbottom were excavated, and Boundary Channel's lagoon enlarged by 30 acres (120,000 m2).[10]

The Pentagon Lagoon was named by The Washington Post after a brutal murder there in September 1944. Virginia police found the nude body of 53-year-old Mrs. Margaret Fitzwater floating in the lagoon on the evening of September 24, 1944. Her throat had been slashed, and she had been raped. Within days, 60-year-old Gardner Tyler "Pop" Holmes, an eccentric who lived on a houseboat anchored in the lagoon, was charged with her murder. It quickly became apparent that Holmes was insane (and had, in fact, escaped from a Virginia mental hospital in 1931). A second throat-slashing murder and rape occurred on Hains Point (almost directly east of Boundary Channel on the D.C. side of the Potomac River) on October 5. This victim was 18-year-old Dorothy Berrum. Investigators quickly found eyewitnesses and a chain of evidence which led them to United States Marine Corps Private Earl McFarland. McFarland was indicted on December 11, 1944, and a jury convicted him of murder after an hour's deliberation on February 1, 1945. He was sentenced to die in the electric chair.[13] On April 3, McFarland and a companion escaped from the D.C. Jail. Two guards were playing cards with them, and the men overpowered them and walked out of the unlocked cell block. An eight-day manhunt covered the entire East Coast before McFarland was recaptured in Knoxville, Tennessee, (his home town) on April 11. His escape led to scathing indictments about the way the D.C. Jail was staffed and managed. President Harry S. Truman declined to give McFarland clemency on July 3, 1946, and the Supreme Court of the United States denied his appeal on July 18. He was executed on July 19.[14]

The phrase "Pentagon lagoon" was first used by the federal government in 1945,[15] but the formal name "Pentagon Lagoon" was not used until 1946.[16]

When the Pentagon Lagoon was surveyed in 2000, the eastern entrance channel was 7.5 feet (2.3 m) deep. Depths of 5 to 8 feet (1.5 to 2.4 m) were common in front of the Columbia Island Marina, while 2 to 7 feet (0.61 to 2.13 m) was common elsewhere in the lagoon.[11]

Crossings

The following bridges cross Boundary Channel, listed from south to north:

| Image | Crossing | Opened | Coordinates | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

George Washington Memorial Parkway Mount Vernon Trail |

1932[17] | 38.8754°N 77.0471°W | Known as Humpback Bridge; widened and pedestrian underpasses added in 2010[18] |

|

Footbridge to Lyndon Baines Johnson Memorial Grove | 38.8789°N 77.0530°W | ||

|

1942[19] | 38.8804°N 77.0573°W | ||

|

George Washington Memorial Parkway southbound | 38.88085°N 77.0589°W | ||

| Memorial Avenue | 1932[20] | 38.8851°N 77.0616°W | ||

|

Arlington Boulevard | 1949[21] | 38.8889°N 77.0641°W | replaced wooden bridge opened in 1938[22] |

|

George Washington Memorial Parkway northbound | 38.8899°N 77.0641°W | ||

| Mount Vernon Trail | 38.88995°N 77.0640°W |

References

- Office of Conservation, Interpretation, and Use, p. 48-49; Moore and Jackson, p. 91.

- Secrest, Meryle. "Park Named for Mrs. Johnson." The Washington Post. November 13, 1968.

- Corps of Engineers, p. 533. Accessed 2013-05-07.

- "Island to Be Remade in New Bridge Plans." The Washington Post. April 15, 1925.

- "Potomac Channel to Be Dredged for Flood Prevention." The Washington Post. April 2, 1925.

- Office of Public Buildings and Public Parks of the National Capital, 1927, p. 20.

- Moore, p. 91.

- "Oil Is Spilled Into Channel From Ft. Myer." The Washington Post. June 14, 1977.

- Severin v. United States, 86 Ct. Cl. 53, 56 (1937).

- Vogel, p. 133.

- National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. United States Coast Pilot. Vol. 3: Atlantic Coast: Sandy Hook, NJ to Cape Henry, VA. 46th ed. Washington, D.C.: u.S. Government Printing Office, 2013, p. 291. Accessed 2013-05-07.

- Ackerman, Stephen J. and Burton, Jon C. "Catch a Train, Catch a Fish." The Washington Post. July 22, 1983.

- Towe, Emily. "FBI Takes Over in Throat-Slashing Mystery of Widow Taken From Lagoon." The Washington Post. September 25, 1944, p. 1; Towe, Emily. "Secret Device Used in Murder Weapon Hunt." The Washington Post. September 26, 1944, p. 1; "7-Hour Lagoon Search Fails to Produce Slaying Weapon." The Washington Post. September 27, 1944, p. 3; "FBI Questions Six Relatives of Slain Woman." The Washington Post. September 30, 1944, p. 7; "'Voluntary Witness' Charged With Pentagon Lagoon Murder." The Washington Post. October 1, 1944, p. 1; "Holmes Sanity Test May Balk Murder Trial." The Washington Post. October 2, 1944, p. 7; "Victim, 17, Raped, Then Strangled." The Washington Post. October 7, 1944, p. 1; "McFarland Indicted in Lagoon Death." The Washington Post. December 12, 1944, p. 1; "McFarland Trial Delayed Until Jan. 29." The Washington Post. January 4, 1945, p. 4; "Death Penalty Is Asked for McFarland." The Washington Post. January 30, 1945, p. 1; Bernstein, Adele. "McFarland's Alibi Jolted As Girl Recants." The Washington Post. January 31, 1945, p. 1; Bernstein, Adele. "McFarland Denies Any Part in Murder as Case Nears Jury." The Washington Post. February 1, 1945, p. 1; Bernstein, Adele. "Jury Returns Guilty Verdict After Hour's Deliberation." The Washington Post. February 2, 1945, p. 1; "McFarland Sentenced to Die June 26." The Washington Post. February 17, 1945, p. 3.

- Hailey, Al and Lewis, Al. "McFarland's Companion in Escape Is Recaptured." The Washington Post. April 4, 1946, p. 1; Hailey, Al and Lewis, Al. "McFarland Manhunt Covers East." The Washington Post. April 5, 1946, p. 1; Hailey, Al. "Jail Guards and Killers Played Cards for a Month." The Washington Post. April 11, 1946, p. 1; Yarborough, Charles and Lewis, Al. "Free for 8 Days and 8 Hours, Unarmed Slayer Tells FBI How He Dodged Police, Rode Freights to His Native State." The Washington Post. April 12, 1946, p. 1; "McFarland Recaptured in Knoxville." The Washington Post. April 12, 1946, p. 1; Hailey, Al. "Botkin Will Be Asked Why Death Row Door In Jail Was Left Open." The Washington Post. April 13, 1946, p. 1; "Marshals Have Difficulty Getting McFarland Into Jail." The Washington Post. April 16, 1946, p. 1; "FBI Report on Jail Suggests Everyone Could Have Got Out." The Washington Post. June 1, 1946, p. 1; "Truman Rejects Clemency Plea of McFarland." The Washington Post. July 4, 1946, p. 1; "McFarland Must Die Today; Vinson Rejects Delay Plea." The Washington Post. July 19, 1946, p. 1; Hailey, Al. "McFarland Dies in Chair, Protesting Innocence to End." The Washington Post. July 20, 1946, p. 1.

- Committee on Interstate and Foreign Commerce, p. 7.

- Subcommittee on Appropriations, p. 147.

- "Boundary Channel Bridge, Spanning Boundary Channel, Washington, District of Columbia, DC". Historic American Engineering Record. Retrieved 2020-12-24.

- Berman, Mark (2007-11-22). "Overhaul of GW Parkway Bridge to Hamper Commute". ISSN 0190-8286. Retrieved 2020-12-24.

- "Pentagon Roadways Named". The Evening Star. 17 December 1943.

- "Arlington Memorial Bridge, Boundary Channel Extension, Spanning Mount Vernon Memorial Highway & Boundary Channel, Washington, District of Columbia, DC". Historic American Engineering Record. Retrieved 2020-12-24.

- "D.C.-Virginia Traffic Eased as Two Projects are Put Into Operation". The Evening Star. 20 September 1949.

- "Legal Matters Delay Opening of Bridge Link." Washington Post. October 19, 1938.

Bibliography

- Army Corps of Engineers. Report of the Chief of Engineers, U.S. Army, 1920. Part 1. United States Army. Washington, D.C.: Government Printing Office, 1920.

- Committee on Interstate and Foreign Commerce. Federal Aid for Public Airports: Hearings Before the Committee on Interstate and Foreign Commerce on H.R. 3170. Committee on Interstate and Foreign Commerce. U.S. House of Representatives. 79th Cong., 1st sess. Washington, D.C.: U.S. Government Printing Office, 1945.

- Moore, John Ezra. Geology, Hydrology, and History of the Washington, D.C., Area. Washington, D.C.: American Geological Institute, 1989.

- Office of Public Buildings and Public Parks of the National Capital. Annual Report of the Director of Public Buildings and Public Parks of the National Capital. Washington, D.C.: Government Printing Office, 1927.

- Subcommittee on Appropriations. Interior Department and Related Agencies Appropriations: Hearings Before a Subcommittee of the Committee on Appropriations of the United States Senate on H.R. 6236. Committee on Appropriations. Senate. United States Congress. 79th Cong., 2d sess. Washington, D.C.: U.S. Government Printing Office, 1946.

- Vogel, Steve. The Pentagon: A History. New York: Random House, 2008.