Theodore Roosevelt Island

Theodore Roosevelt Island is an 88.5-acre (358,000 m2) island and national memorial located in the Potomac River in Washington, D.C.[1][2] The island was given to the federal government by the Theodore Roosevelt Association in memory of the 26th president, Theodore Roosevelt. Until then, the island had been known as My Lord's Island, Barbadoes Island, Mason's Island, Analostan Island, and Anacostine Island.[3]

| Theodore Roosevelt Island National Memorial | |

|---|---|

IUCN category III (natural monument or feature) | |

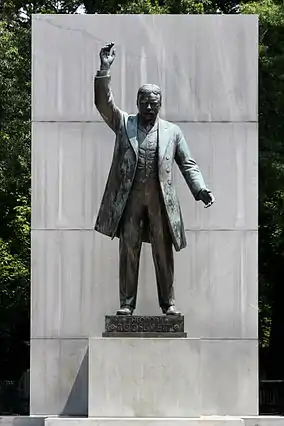

17-foot Centerpiece Statue | |

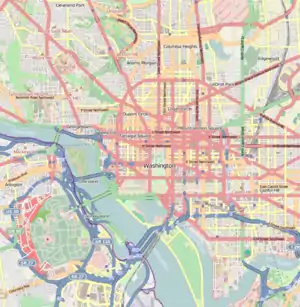

Location within Washington, D.C.  Theodore Roosevelt Island (the United States) | |

| Location | The Potomac River in Washington, D.C., U.S. |

| Coordinates | 38°53′50″N 77°3′51″W |

| Area | 88.5 acres (35.8 ha) |

| Max. elevation | 44 feet (13 m) |

| Established | May 21, 1932 |

| Visitors | 160,000 (in 2015) |

| Governing body | National Park Service |

| Website | Theodore Roosevelt Island |

The island is maintained by the National Park Service, as part of the nearby George Washington Memorial Parkway.[2] The land is generally maintained as a natural park, with various trails and a memorial plaza featuring a statue of Roosevelt. No cars or bicycles are permitted on the island, which is reached by a footbridge from Arlington, Virginia, on the western bank of the Potomac.

"In the 1930s landscape architects transformed Mason’s Island from neglected, overgrown farmland into Theodore Roosevelt Island, a memorial to America’s 26th president. They conceived a 'real forest' designed to mimic the natural forest that once covered the island. Today miles of trails through wooded uplands and swampy bottomlands honor the legacy of a great outdoorsman and conservationist."[4]

A small island, "Little Island," lies just off the southern tip; Georgetown and the John F. Kennedy Center for the Performing Arts are respectively across the main channel of the Potomac to the north and the east.

History

The Nacotchtank Indians, formerly of what is now Anacostia (in Washington, D.C.), temporarily moved to the island in 1668, giving its first recorded name, "Anacostine". The island was patented in 1682 as Anacostine Island by Captain Randolph Brandt (or Brunett), who left the island to his daughter Margaret Hammersley, upon his death in 1698 or 1699.[5][6]

The island was acquired by George Mason III in 1724.[7] George Mason IV acquired the island in 1735 upon the death of his father and John Mason, the son of George Mason IV, inherited the Island in 1792 and owned it until 1833.[5] John Mason built a mansion around 1796 and planted gardens there in the early 19th century. The Masons left the island in 1831 when a causeway stagnated the water. Following Mason's death in 1842, John Carter acquired the land.[6] After Carter died in 1851, the island passed to William A. Bradley.[6] From 1913 to 1931, the island was owned by the Washington Gas Light Company, which allowed vegetation to grow unchecked on the island.[5] By 1935, the Civilian Conservation Corps had cleared much of the island and pulled down the remaining walls of the house; today, only part of the mansion's foundation remains.

The island was used as a training camp by the 1st United States Colored Infantry on its formation in 1863. From 1864 to 1865, the camp housed as many as 1,200 Contraband (American Civil War), formerly enslaved people under the authority of the US Army, and later, the Freedmen's Bureau.[8] Locals continued to call it "Mason's Island" until the memorial was built.[9]

The Mason House in the 19th Century

The Mason House in the 19th Century Union soldiers on the island in 1861

Union soldiers on the island in 1861_Island%252C_Washington%252C_D.C._(Ground_plan%252C_view_and_cross_section_of_one_of_the..._-_NARA_-_305820.jpg.webp) Contraband Quarters, Mason's Island

Contraband Quarters, Mason's Island

Following the declaration of war against Spain in 1898, the island was used as a test site for a number of private experiments in electrical ignition of the explosives dynamite and jovite led by the chemist Charles Edward Munroe of Columbian University.[10] Monroe's experiments, which explored the use of the explosives for mining waterways and roadways and preparing ground for rapid entrenchment, were conducted in secret and without alerting the District of Columbia Police Department, which investigated citizens' reports of Spanish spy activity and found the explosives and detonators buried on the island.[10]

National memorial

In 1931, the Theodore Roosevelt Memorial Association purchased the island from the gas company with the intention of erecting a memorial honoring Roosevelt.[5] Congress authorized the memorial on May 21, 1932, but did not appropriate funds for the memorial for almost three decades.

Funds were finally designated by Congress in 1960. As with all historic areas administered by the National Park Service, the national memorial is listed on the National Register of Historic Places; the listing first appeared on October 15, 1966.

The memorial was dedicated on October 27, 1967.[11] Designed by Eric Gugler, the memorial includes a 17-foot (5 m) statue by sculptor Paul Manship, four large stone monoliths with some of Roosevelt's more famous quotations, and two large fountains.

Geography and natural history

The Potomac River surrounding the island is at sea level, part of the Chesapeake Bay estuary, with the river water fresh but tidal. A narrow channel, unofficially referred to as "Little River" by local users of the Potomac River, separates the island from the Virginia bank of the Potomac, with the main channel of the Potomac between the island and Georgetown, part of Washington, D.C. Surrounding scenery includes the Potomac Gorge and Key Bridge, Georgetown, Rosslyn, and the Kennedy Center. The Virginia state line follows the southern bank of the river, so, despite the fact that the primary access to the island is from Virginia, the island itself is entirely in the District of Columbia.

The rocky western (upriver) and central portions of the island are part of the Piedmont Plateau, while the southeastern part is within the Atlantic Coastal Plain. At one point opposite Georgetown, the Atlantic Seaboard fall line between the Piedmont and the Coastal Plain can be seen as a natural phenomenon. The island has about 2.5-mile (4.0 km) of shoreline,[2] and the highest area of the island (where the Mason mansion stood) is about 44 feet (13 m) above sea level.

Spring floods coming down the Potomac from Appalachia inundate low-lying portions of island's shores regularly, usually several times each year, while much larger floods, often from the storm surges and intense, widespread rainfall from coastal hurricanes and tropical storms, flood the island more deeply several times a century.

The island's vegetation is quite diverse for a relatively small area, due to its geological and topographic variety, the frequency of floods, its land-use history (including various periods of landscaping), and its location in an urban area in which many non-native species occur. Most of the island is deciduous forest of various kinds, including uplands, riparian shores, and swamps. There is also an area of fresh-water tidal (estuarine) marsh, and a few small bedrock outcrops of metamorphic Piedmont rock, some along the tidal shore. The variety of freshwater estuarine intertidal habitats along the island's shores is particularly notable.

The island is particularly known for its variety of birds and its showy displays of spring wildflowers. However, dozens of non-native invasive plants have become abundant there, often outcompeting the native species.

Access

Theodore Roosevelt Island is accessible by a footbridge from a parking lot along the Virginia bank of the Potomac River, just north of the Theodore Roosevelt Bridge, which crosses but does not allow access to the island. Cars can enter this parking lot only from the northbound lanes of the George Washington Memorial Parkway.

Pedestrians and bicyclists can reach the parking lot and footbridge by following the Mount Vernon Trail south from the intersection of Lee Highway and N. Lynn St. in Rosslyn, near Key Bridge. The closest Washington Metro station to the island is the Rosslyn station.[12]

Several hiking trails provide access to the memorial and a variety of the island's natural habitats, including a boardwalk through a swampy and marshy area.[2]

In popular culture

- A story by Ernest Seton Thompson "The Royal Analostan" mentions the island as the origin of the fictional cat breed.

- The 2014 movie Captain America: The Winter Soldier depicted the island as the site of the Triskelion, the headquarters of the fictional S.H.I.E.L.D. spy agency.[13]

- In 2019 video game Tom Clancy's The Division 2 the island was the site of a failed quarantine effort after the outbreak of a manufactured epidemic disease. The citizens quarantined on the island radicalized into a group called the "Outcasts", one of the game's major antagonist factions.

See also

References

- National Park Service. "Listing of area as of 09/30/2005" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on October 14, 2006. Retrieved May 5, 2006.

- "Theodore Roosevelt Island". U.S. National Park Service. Retrieved 25 June 2011.

- "Theodore Roosevelt Island". U.S. Geographic Survey: Geographic Names Information System. Retrieved 2009-01-13.

- "Theodore Roosevelt Island (U.S. National Park Service)". www.nps.gov. Retrieved 2016-02-29.

- Curry, Mary E. (1971–1972). "Theodore Roosevelt Island: A Broken Link to Early Washington, D.C. History". Records of the Columbia Historical Society.

- Proctor, John Clagett (1949). Proctor's Washington and Environs. John Clagett Proctor, LL.D. p. 98.

- James W. Foster, "Potomac River Maps of 1737 by Robert Brooke and Others," William and Mary College Quarterly Historical Magazine 2nd Ser., Vol. 18, No. 4. (October 1938), 410.

- Harrison, Robert (2011). Washington during Civil War and Reconstruction: Race and Radicalism. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press. p. 46.

- "Theodore Roosevelt Island". worldsiteguides.com. Retrieved 2016-02-29.

- Brooks, Edward M. (21 May 1898). "Trials With Explosives". Boston Evening Transcript. Retrieved 14 August 2014.

- The National Parks: Index 2001–2003. Washington: U.S. Department of the Interior.

- "NPS: Theodore Roosevelt Island".

- Merchant, Canaan (February 7, 2014). "Captain America obliterates Rosslyn and Roosevelt Island". Greater Greater Washington. Retrieved July 16, 2015.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Theodore Roosevelt Island. |

- Official website

- Theodore Roosevelt Association

- Historic American Landscapes Survey (HALS) No. DC-12, "Theodore Roosevelt Island"

- Historic American Buildings Survey (HABS) No. DC-28, "General John Mason House", formerly located on island

- Friends of Theodore Roosevelt Island