Brazzaville Conference

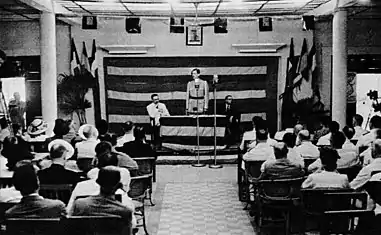

The Brazzaville Conference (French: Conference de Brazzaville) was a meeting of prominent Free French leaders held in January 1944 in Brazzaville, the then-capital of French Equatorial Africa, during World War II.

After the Fall of France to Nazi Germany, the pro-Nazi Vichy France regime controlled the colonies. One by one they peeled off and switched their allegiance to the Free France movement led by Charles de Gaulle. In January 1944, Free French politicians and high-ranking colonial officials from the French African colonies met in Brazzaville in the modern-day Republic of the Congo. The conference recommended political, social, and economic reforms and led to the agreement on the Brazzaville Declaration.

De Gaulle believed that the survival of France depended on support from these colonies, and he made numerous concessions. They included the end of forced labor, the end of special legal restrictions that applied to natives but not to whites, the establishment of elected territorial assemblies, representation in Paris in a new "French Federation", and the eventual entry of black Africans in the French Assembly. however, independence was explicitly rejected as a future possibility:

- The ends of the civilizing work accomplished by France in the colonies excludes any idea of autonomy, all possibility of evolution outside the French bloc of the Empire; the eventual Constitution, even in the future of self-government in the colonies is denied.[1]

Context

Part of a series on the |

|---|

|

|

|

During World War II, the French colonial empire played an essential role in the liberation of France through its gradual alignment with Free France. After the end of the Tunisia campaign, the entire colonial empire reunited in favor of the Allied forces; with the exception of French Indochina, which remained loyal to the Vichy government.

Because of this role the French Committee of National Liberation began questioning the future of the colonies. The war created many difficulties for local people, and saw the growth of nationalist aspirations and tensions between communities in French North Africa; particularly in Algeria and Tunisia. In addition, the French were being aided by the US, which opposed colonialism. In Madagascar, the month of occupation by the United Kingdom after the invasion of the island had weakened French authority.

René Pleven, Commissioner for the Colonies in the French Committee of National Liberation, wanted to avoid international arbitration of the future of the French Empire, and in that regard organized the Brazzaville conference, in French Equatorial Africa.

The Conference

Initially, the French Committee of National Liberation wanted to include all the governors from all free territories, but due to war difficulties, the Committee only included administrative représentants from French territories in Africa, which had already joined de Gaulle and René Pleven. Invitations were sent to 21 governors, nine members of the Consultative Assembly, and six observers from Algeria, Tunisia, and Morocco.

De Gaulle opened the Conference by saying he wanted to build new foundations for France after years under the domination of Philippe Pétain and his authoritarian regime. There was also a seemingly more open tone towards the French colonies. De Gaulle wanted to renew the relationship between France and "French Africa."

The Brazzaville Conference is still regarded as a turning point for France and its colonial empire. Many historians view it as the first step towards decolonization, albeit a precarious one.

Conclusions

The Brazzaville Declaration included the following points:

- The French Empire would remain united.

- Semi-autonomous assemblies would be established in each colony.

- Citizens of France's colonies would share equal rights with French citizens.

- Citizens of French colonies would have the right to vote for the French parliament.

- The native population would be employed in public service positions within the colonies.

- Economic reforms would be made to diminish the exploitative nature of the relationship between France and its colonies.

However, the possibility of complete independence was soundly rejected. As de Gaulle stated:

The aims of France's civilizing mission preclude any thought of autonomy or any possibility of development outside the French empire. Self-government must be rejected - even in the more distant future.[2]

References

- Tony Smith, "A Comparative Study of French and British Decolonization" Comparative Studies in Society and History 20#1 (1978), pp. 70-102, quoting page 73

- Low, Donald Anthony, Britain and Indian Nationalism: The Imprint of Amibiguity 1929–1942 Cambridge University Press, 1997, p. 16