Decolonisation of Africa

The decolonisation of Africa took place in the mid-to-late 1950s to 1975, with sudden and radical regime changes on the continent as colonial governments made the transition to independent states. Often quite unorganized, and marred with violence, political turmoil, and widespread unrest, organized revolts in both northern and sub-Saharan colonies including the Algerian War in French Algeria, the Angolan War of Independence in Portuguese Angola, the Congo Crisis in the Belgian Congo, and the Mau Mau Uprising in British Kenya.[1][2][3][4][5]

Background

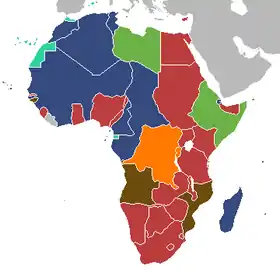

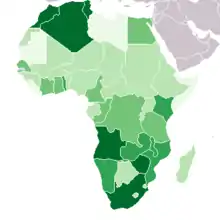

The "Scramble for Africa" between 1870 and 1900 ended with almost all of Africa being controlled by a small number of European states. Racing to secure as much land as possible while avoiding conflict amongst themselves, the partition of Africa was confirmed in the Berlin Agreement of 1885, with little regard to local differences.[6][7] By 1905, control of almost all African soil was claimed by Western European governments, with the only exceptions being Liberia (which had been settled by African-American former slaves) and Ethiopia (then occupied by Italy in 1936).[8] Britain and France had the largest holdings, but Germany, Spain, Italy, Belgium, and Portugal also had colonies. As a result of colonialism and imperialism, a majority of Africa lost sovereignty and control of natural resources such as gold and rubber. The introduction of imperial policies surfacing around local economies led to the failing of local economies due to an exploitation of resources and cheap labor.[9] Progress towards independence was slow up until the mid-20th century. By 1977, 54 African countries had seceded from European colonial rulers.[10]

Causes

External causes

During the world wars, African soldiers were conscripted into imperial militaries.[11] This led to a deeper political awareness and the expectation of greater respect and self-determination, which was left largely unfulfilled.[12] During the 1941 Atlantic Conference, the British and the US leaders met to discuss ideas for the post-war world. One of the provisions added by President Roosevelt was that all people had the right to self-determination, inspiring hope in British colonies.[10]

On February 12, 1941, United States President Franklin D. Roosevelt and British Prime Minister Winston Churchill met to discuss the postwar world. The result was the Atlantic Charter.[13] It was not a treaty and was not submitted to the British Parliament or the Senate of the United States for ratification, but it turned out to be a widely acclaimed document.[14] One of the provisions, introduced by Roosevelt, was the autonomy of imperial colonies. After World War II, the US and the African colonies put pressure on Britain to abide by the terms of the Atlantic Charter. After the war, some Britons considered African colonies to be childish and immature; British colonisers introduced democratic government at local levels in the colonies. Britain was forced to agree but Churchill rejected universal applicability of self-determination for subject nations. He also stated that the Charter was only applicable to German occupied states, not to the British Empire.[10]

Furthermore, colonies such as Nigeria, Senegal and Ghana pushed for self-governance as colonial powers were exhausted by war efforts.[15]

Internal causes

Colonial economic exploitation involved the siphoning off of resource extraction (such as mining) profits to European shareholders at the expense of internal development, causing major local socioeconomic grievances.[16] For early African nationalists, decolonisation was a moral imperative around which a political power base could be assembled.

In the 1930s, the colonial powers had cultivated, sometimes inadvertently, a small elite of local African leaders educated in Western universities, where the became familiar with and fluent in ideas such as self-determination. Although independence was not encouraged, arrangements between these leaders and the colonial powers developed, [9] and such figures as Jomo Kenyatta (Kenya), Kwame Nkrumah (Gold Coast, now Ghana), Julius Nyerere (Tanganyika, now Tanzania), Léopold Sédar Senghor (Senegal), Nnamdi Azikiwe (Nigeria), and Félix Houphouët-Boigny (Côte d'Ivoire) came to lead the struggles for African nationalism.

During the second world war, some local African industry and towns expanded when U-boats patrolling the Atlantic Ocean reduced raw material transportation to Europe.[10]

Over time, urban communities, industries and trade unions grew, improving literacy and education, leading to pro-independence newspaper establishments.[10]

By 1945 the Fifth Pan-African Congress demanded the end of colonialism, and delegates included future presidents of Ghana, Kenya, Malawi and national activists.[17]

Economic legacy

There is an extensive body of literature that has examined the legacy of colonialism and colonial institutions on economic outcomes in Africa, with numerous studies showing disputed economic effects of colonialism.[18]

The economic legacy of colonialism is difficult to quantify and is disputed. Modernisation theory posits that colonial powers built infrastructure to integrate Africa into the world economy, however, this was built mainly for extraction purposes. African economies were structured to benefit the coloniser and any surplus was likely to be ‘drained’, thereby stifling capital accumulation.[19] Dependency theory suggests that most African economies continued to occupy a subordinate position in the world economy after independence with a reliance on primary commodities such as copper in Zambia and tea in Kenya.[20] Despite this continued reliance and unfair trading terms, a meta-analysis of 18 African countries found that a third of countries experienced increased economic growth post-independence.[19]

Social legacy

Language

Scholars including Dellal (2013), Miraftab (2012) and Bamgbose (2011) have argued that Africa's linguistic diversity has been eroded. Language has been used by western colonial powers to divide territories and create new identities which has led to conflicts and tensions between African nations.[21]

Law

In the immediate post-independence period, African countries largely retained colonial legislation. However, by 2015 much colonial legislation had been replaced by laws that were written locally.[22]

Transition to independence

Following World War II, rapid decolonisation swept across the continent of Africa as many territories gained their independence from European colonisation.

In August 1941, United States President Franklin D. Roosevelt and British Prime Minister Winston Churchill met to discuss their post-war goals. In that meeting, they agreed to the Atlantic Charter, which in part stipulated that they would, "respect the right of all peoples to choose the form of government under which they will live; and they wish to see sovereign rights and self government restored to those who have been forcibly deprived of them."[23] This agreement became the post-WWII stepping stone toward independence as nationalism grew throughout Africa.

Consumed with post-war debt, European powers were no longer able to afford the resources needed to maintain control of their African colonies. This allowed for African nationalists to negotiate decolonisation very quickly and with minimal casualties. Some territories, however, saw great death tolls as a result of their fight for independence.

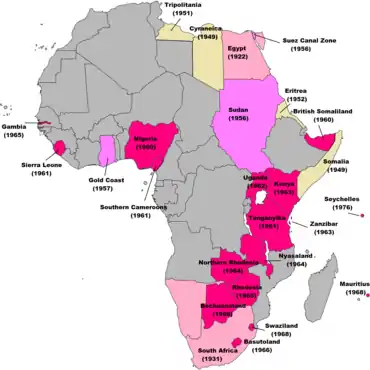

British Empire

Sudan

On January 1st 1956, Sudan (formerly Anglo-Egyptian Sudan) became the first sub-Saharan African country to gain its independence from European colonization.

Ghana

On 6 March 1957, Ghana (formerly the Gold Coast) became the second sub-Saharan African country to gain its independence from European colonisation.[24] Starting in 1945 Pan-African Congress, Gold Coast's British- and American-educated independence leader Kwame Nkrumah made his focus clear. In the conference's declaration, he wrote, “we believe in the rights of all peoples to govern themselves. We affirm the right of all colonial peoples to control their own destiny. All colonies must be free from foreign imperialist control, whether political or economic.”[25]

In 1949, the conflict would ramp up when British troops opened fire on African protesters. Riots broke out across the territory and while Nkrumah and other leaders ended up in prison, the event became a catalyst for the independence movement. After being released from prison, Nkrumah founded the Convention People's Party (CPP), which launched a mass-based campaign for independence with the slogan ‘Self Government Now!’”[26] Heightened nationalism within the country grew their power and the political party widely expanded. In February of 1951, the Convention People's Party gained political power by winning 34 of 38 elected seats, including one for Nkrumah who was imprisoned at the time. London revised the Gold Coast Constitution to give Blacks a majority in the legislature in 1951. In 1956 they requested independence inside the Commonwealth, which was granted peacefully in 1957 with Nkrumah as prime minister and Queen Elizabeth II as sovereign.[27]

Winds of Change

Prime Minister Harold Macmillan gave the famous "Wind of Change" speech in South Africa in February 1960, where he spoke of "the wind of change blowing through this continent".[28] Macmillan urgently wanted to avoid the same kind of colonial war that France was fighting in Algeria. Under his premiership decolonisation proceeded rapidly.[29]

Britain's remaining colonies in Africa, except for Southern Rhodesia, were all granted independence by 1968. British withdrawal from the southern and eastern parts of Africa was not a peaceful process. Kenyan independence was preceded by the eight-year Mau Mau Uprising. In Rhodesia, the 1965 Unilateral Declaration of Independence by the white minority resulted in a civil war that lasted until the Lancaster House Agreement of 1979, which set the terms for recognised independence in 1980, as the new nation of Zimbabwe.[30]

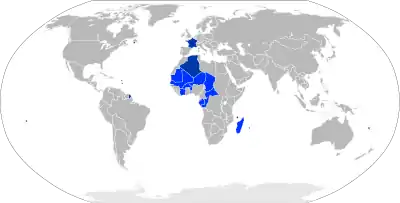

French colonial empire

The French colonial empire began to fall during the Second World War when the Vichy France regime controlled the Empire. But one after another most of the colonies were occupied by foreign powers (Japan in Indochina, Britain in Syria, Lebanon, and Madagascar, the United States and Britain in Morocco and Algeria, and Germany and Italy in Tunisia). However, control was gradually reestablished by Charles de Gaulle, who uses colonial base as a launching point to expel Vichy from Metropolitan France. De Gaulle together with most Frenchmen was committed to preserving the Empire in the new form. The French Union, included in the Constitution of 1946, nominally replaced the former colonial empire, but officials in Paris remained in full control. The colonies were given local assemblies with only limited local power and budgets. There emerged a group of elites, known as evolués, who were natives of the overseas territories but lived in metropolitan France.[32][33][34]

De Gaulle assembled a major conference of Free France colonies in Brazzaville, in Africa, in January–February, 1944. The survival of France depended on support from these colonies, and De Gaulle made numerous concessions. They included the end of forced labor, the end of special legal restrictions that apply to natives but not to whites, the establishment of elected territorial assemblies, representation in Paris in a new "French Federation", and the eventual representation of Sub-Saharan Africans in the French Assembly. However, Independence was explicitly rejected as a future possibility:

- The ends of the civilizing work accomplished by France in the colonies excludes any idea of autonomy, all possibility of evolution outside the French bloc of the Empire; the eventual Constitution, even in the future of self-government in the colonies is denied.[35]

Conflict

France was immediately confronted with the beginnings of the decolonisation movement. In Algeria demonstrations in May 1945 were repressed with an estimated 6,000 Algerians killed.[36] Unrest in Haiphong, Indochina, in November 1945 was met by another warship bombarding the city.[37] Paul Ramadier's (SFIO) cabinet repressed the Malagasy Uprising in Madagascar in 1947. French officials estimated the number of Malagasy killed from a low of 11,000 to a French Army estimate of 89,000.[38]

In France's African colonies, Cameroun, the Union of the Peoples of Cameroon's insurrection, started in 1955 and headed by Ruben Um Nyobé, was violently repressed over a two-year period, with perhaps as many as 100 people killed.

Algeria

French involvement in Algeria stretched back a century. Ferhat Abbas and Messali Hadj's movements had marked the period between the two wars, but both sides radicalised after the Second World War. In 1945, the Sétif massacre was carried out by the French army. The Algerian War started in 1954. Atrocities characterized both sides, and the number killed became highly controversial estimates that were made for propaganda purposes.[39] Algeria was a three-way conflict due to the large number of "pieds-noirs" (Europeans who had settled there in the 125 years of French rule). The political crisis in France caused the collapse of the Fourth Republic, as Charles de Gaulle returned to power in 1958 and finally pulled the French soldiers and settlers out of Algeria by 1962.[40][41] Lasting more than eight years, the estimated death toll typically falls between 300,000 and 400,000 people.[42] By 1958, the FLN was able to negotiate peace accord with French President Charles de Gaulle and nearly 90% of all Europeans had left the territory.

French Community

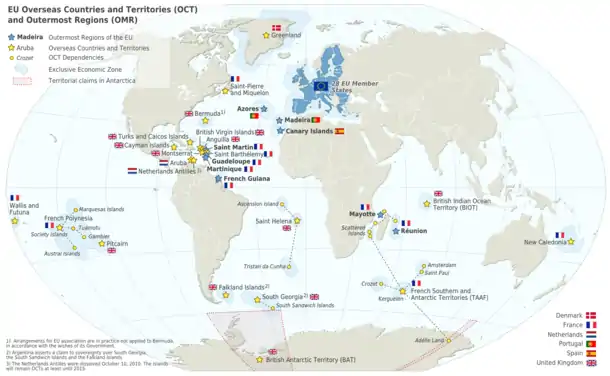

The French Union was replaced in the new 1958 Constitution of 1958 by the French Community. Only Guinea refused by referendum to take part in the new colonial organisation. However, the French Community dissolved itself in the midst of the Algerian War; almost all of the other African colonies were granted independence in 1960, following local referendums. Some few colonies chose instead to remain part of France, under the status of overseas départements (territories). Critics of neocolonialism claimed that the Françafrique had replaced formal direct rule. They argued that while de Gaulle was granting independence on one hand, he was creating new ties with the help of Jacques Foccart, his counsellor for African matters. Foccart supported in particular the Nigerian Civil War during the late 1960s.[43]

Robert Aldrich argues that with Algerian independence in 1962, it appeared that the Empire practically had come to an end, as the remaining colonies were quite small and lacked active nationalist movements. However, there was trouble in French Somaliland (Djibouti), which became independent in 1977. There also were complications and delays in the New Hebrides Vanuatu, which was the last to gain independence in 1980. New Caledonia remains a special case under French suzerainty.[44] The Indian Ocean island of Mayotte voted in referendum in 1974 to retain its link with France and forgo independence.[45]

Timeline

This table is the arranged by the earliest date of independence in this graph; 58 countries have seceded.

Timeline notes

- Explanatory notes are added in cases where decolonisation was achieved jointly by multiple countries or where the current country is formed by the merger of previously decolonised countries. Although Ethiopia was administered as a colony in the aftermath of the Second Italo-Ethiopian War and was recognized by the international community as such at the time, it is not listed here as its brief period under Italian rule (which lasted for a little more than five years and ended with the return of the previous native government) is now usually seen as a military occupation.

- Some territories changed hands multiple times, so only the last colonial power is mentioned in the list. In addition, the mandatory or trustee powers are mentioned for territories that were League of Nations mandates and UN Trust Territories.

- The dates of decolonisation for territories annexed by or integrated into previously decolonised independent countries are given in separate notes, as are dates when a Commonwealth realm abolished its monarchy.

- For countries that became independent either as a Commonwealth realm, a monarchy with a strong Prime Minister, or a parliamentary republic, the head of government is listed instead.

- Liberia would later annexed the Republic of Maryland, another settler colony made up of former African-American slaves, in 1857. Liberia would not be recognized by the United States until 5 February 1862.

- Stephen Allen Benson was President on the date of the United States' recognition.

- As Union of South Africa.

- The Union of South Africa was constituted through the South Africa Act entering into force on 31 May 1910. On 11 December 1931 it got increased self-governance powers through the Statute of Westminster which was followed by transformation into republic after the 1960 referendum. Afterwards, South Africa was under apartheid until elections resulting from the negotiations to end apartheid in South Africa on 27 April 1994 when Nelson Mandela became president.

- As the Kingdom of Egypt. Transcontinental country, partially located in Asia.

- On 28 February 1922 the British government issued the Unilateral Declaration of Egyptian Independence. Through this declaration, the British government unilaterally ended its protectorate over Egypt and granted it nominal independence with the exception of four "reserved" areas: foreign relations, communications, the military and the Anglo-Egyptian Sudan.[46] The Anglo-Egyptian treaty of 1936 reduced British involvement, but still was not welcomed by Egyptian nationalists, who wanted full independence from Britain, which was not achieved until 23 July 1952. The last British troops left Egypt after the Suez Crisis of 1956.

- Although the leaders of the 1952 revolution (Mohammed Naguib and Gamal Abdel Nasser) became the de facto leaders of Egypt, neither would assume office until September 17 of that year when Naguib became Prime Minister, succeeding Aly Maher Pasha who was sworn in on the day of the revolution. Nasser would succeeded Naguib as Prime Minister on 25 February 1954.

- From 1 April 1941 to its eventual transfer to Ethiopia, Italian Eritrea was occupied by the United Kingdom.

- Date marking the de jure end of Italian rule. The transfer of Eritrea to the Ethiopian Empire occurred on 15 September 1952. On 24 May 1993, after decades of fighting starting from 1 September 1961, Eritrea formally seceded from Ethiopia.

- Emperor of Ethiopia on the date of the transfer. Isaias Afwerki became President of Eritrea upon independence.

- As the United Kingdom of Libya.

- From 1947, Libya was administrated by the Allies of World War II (United Kingdom and France). Part of the British Military Administration originally gained independence as the Cyrenaica Emirate; it was only recognized by the United Kingdom. The Cyrenaica Emirate also merged to form the United Kingdom of Libya.

- Anglo-Egyptian Condominium Agreement of 1899, stated that Sudan should be jointly governed by Egypt and Britain, but with real power remaining in British hands.[48]

- Before Sudan even gained its independence, on 18 August 1955 the southern area of Sudan began fighting for greater autonomy. After the signing of the Addis Ababa Agreement on 28 February 1972, South Sudan was granted autonomous rule. On 5 June 1983, however, the Sudan government revoke this autonomous rule, igniting a new war for control of South Sudan. (The main non-government combatant of the Second Sudanese Civil War largely claimed to be fighting for a united, secular Sudan rather than South Sudan's independence.) On 9 July 2005, in accordance to the Comprehensive Peace Agreement signed on 9 January of that year, the Southern Sudan Autonomous Region was restored; exactly six years later, in the aftermath of the 9–15 January 2011 South Sudanese independence referendum, South Sudan became independent.

- Salva Kiir Mayardit became President of South Sudan upon independence. Abel Alier was the first President of the High Executive Council of the Southern Sudan Autonomous Region, while John Garang became its President following its restoration.

- Sudan's independence is indirectly linked to the Egyptian revolution of 1952, whose leaders eventually denounced Egypt's claim over Sudan. (This revocation would force the British to end the condominium.)

- As the Kingdom of Tunisia.

- See Tunisian independence.

- Cape Juby was ceded by Spain to Morocco on 2 April 1958. Ifni was returned from Spain to Morocco on 4 January 1969.

- As the Dominion of Ghana.

- The British Togoland mandate and trust territory was integrated into Gold Coast colony on 13 December 1956. On 1 July 1960 Ghana formally abolished its Commonwealth monarchy and became a republic.

- Originally as Prime Minister; became President upon the monarchy's abolition.

- After the French Cameroun mandate and trust territory gained independence it was joined by part of the British Cameroons mandate and trust territory on 1 October 1961. The other part of British Cameroons joined Nigeria.

- Minor armed insurgency from Union of the Peoples of Cameroon.

- Senegal and French Sudan gained independence on 20 June 1960 as the Mali Federation, which dissolved a few months later into present day Senegal and Mali.

- As the Malagasy Republic.

- The Malagasy Uprising was an earlier armed uprising that failed to gain independence from France.

- As the Republic of the Congo.

- Joseph Kasa-Vubu became President upon independence.

- The Congo Crisis occurred after independence.

- As the Somali Republic.

- The Trust Territory of Somalia (former Italian Somaliland) united with the State of Somaliland (former British Somaliland) on 1 July 1960 to form the Somali Republic (Somalia).

- As the Republic of Dahomey.

- As Upper Volta.

- Part of the British Cameroons mandate and trust territory on 1 October 1961 joined Nigeria. The other part of British Cameroons joined the previously decolonised French Cameroun mandate and territory.

- After both gained independence Tanganyika and Zanzibar merged on 26 April 1964 as Tanzania.

- As the Kingdom of Burundi.

- Assumed office on September 27, 1962 as Prime Minister. From the date of independence to Ben Bella's inauguration, Abderrahmane Farès served as President of the Provisional Executive Council.

- Abolished its commonwealth monarchy exactly one year later; Jamhuri Day ("Republic Day") is a celebration of both dates.

- The Mau Mau Uprising was an earlier armed uprising that failed to gain independence from the United Kingdom.

- The Sultanate of Zanzibar would later be overthrown within a month of sovereignty by the Zanzibar Revolution.

- Abolished its commonwealth monarchy exactly two years later.

- Abolished its commonwealth monarchy on 24 April 1970.

- Due to Rhodesia's unwillingness to accommodate the British government's request for black majority rule, the United Kingdom (along with the rest of the international community) refused to recognize the white-minority led government. The former self-governing colony would not be recognized as an independent state until the aftermath of the Rhodesian Bush War, under the name Zimbabwe.

- Botswana Day Holiday is the second day of the two-day celebration of Botswana's independence. The first day is also referred to as Botswana Day.

- Moshoeshoe II became King upon independence.

- Not celebrated as a holiday. The date 24 September 1973 (when the PAIGC formally declared Guinea's independence) is celebrated as Guinea-Bissau's date of independence.

- As the People's Republic of Mozambique

- Pedro Pires was sworn in as Prime Minister three days after independence.

- Although the fight for Cape Verdean independence was linked to the liberation movement occurring in Guinea-Bissau, the island country itself saw little fighting.

- As the People's Republic of Angola

- The Spanish colonial rule de facto terminated over the Western Sahara (then Spanish Sahara), when the territory was passed on to and partitioned between Mauritania and Morocco (which annexed the entire territory in 1979). The decolonisation of Western Sahara is still pending, while a declaration of independence has been proclaimed by the Saharawi Arab Democratic Republic, which controls only a small portion east of the Moroccan Wall. The UN still considers Spain the legal administrating country of the whole territory,[49] awaiting the outcome of the ongoing Manhasset negotiations and resulting election to be overseen by the United Nations Mission for the Referendum in Western Sahara. However, the de facto administrator is Morocco (see United Nations list of Non-Self-Governing Territories).

See also

References

- John Hatch, Africa: The Rebirth of Self-Rule (1967)

- William Roger Louis, The transfer of power in Africa: decolonization, 1940-1960 (Yale UP, 1982).

- Birmingham, David (1995). The Decolonization of Africa. Routledge. ISBN 1-85728-540-9.

- John D. Hargreaves, Decolonization in Africa (2014).

- for the viewpoint from London and Paris see Rudolf von Albertini, Decolonization: the Administration and Future of the Colonies, 1919-1960 (Doubleday, 1971).

- "Berlin Conference of 1884-1885". www.oxfordreference.com. Retrieved 11 January 2015.

- "A Brief History of the Berlin Conference". teacherweb.ftl.pinecrest.edu. Archived from the original on 15 February 2018. Retrieved 11 January 2015.

- Evans, Alistair. "Countries in Africa Considered Never Colonized". africanhistory.about.com. Retrieved 11 January 2015.

- Hunt, Michael (2017). The World Transformed 1945 to the Present. New York: Oxford University Press. p. 264. ISBN 9780199371020.

- , DECOLONISATION OF AFRICA. (2017). HISTORY AND GENERAL STUDIES.

- , "The call of the Empire, the call of the war", Telegraph.

- Ferguson, Ed, and A. Adu Boahen. (1990). "African Perspectives On Colonialism." The International Journal Of African Historical Studies 23 (2): 334. doi:10.2307/219358.

- "The Atlantic Conference & Charter, 1941". history.state.gov. Retrieved 26 January 2015.

The Atlantic Charter was a joint declaration released by U.S. President Franklin D. Roosevelt and British Prime Minister Winston Churchill on August 14, 1941 following a meeting of the two heads of state in Newfoundland.

- Karski, Jan (2014). The Great Powers and Poland: From Versailles to Yalta. Rowman & Littlefield. p. 330. ISBN 9781442226654. Retrieved 24 June 2014.

- Assa, O. (2006). A History of Africa. Volume 2. Kampala East Africa Education Publisher ltd.

- [Boahen, A. (1990) Africa Under Colonial Domination, Volume 7]

- , A ‘Wind Of Change’ That Transformed The Continent | Africa Renewal Online. 2017. Un.Org.

- Michalopoulos, Stelios; Papaioannou, Elias (2020-03-01). "Historical Legacies and African Development". Journal of Economic Literature. 58 (1): 53–128. doi:10.1257/jel.20181447. ISSN 0022-0515.

- Bertocchia, G. & Canova, F., (2002) Did colonization matter for growth? An empirical exploration into the historical causes of Africa's underdevelopment. European Economic Review, Volume 46, pp. 1851-1871

- Vincent Ferraro, "Dependency Theory: An Introduction," in The Development Economics Reader, ed. Giorgio Secondi (London: Routledge, 2008), pp. 58-64

- IMF Country Report No. 17/80 (2017). Article Iv Consultation - Press Release; Staff Report; And Statement By The Executive Director For Nigeria.

- Berinzon, Maya; Briggs, Ryan (1 July 2016). "Legal Families Without the Laws: The Fading of Colonial Law in French West Africa". American Journal of Comparative Law. 64 (2): 329–370. doi:10.5131/AJCL.2016.0012.

- "Atlantic Charter", August 14, 1941, https://www.nato.int/cps/en/natohq/official_texts_16912.htm

- Esseks, John D. "Political independence and economic decolonisation: the case of Ghana under Nkrumah." Western Political Quarterly 24.1 (1971): 59-64.

- Nkrumah, Kwame, Fifth Pan-African Congress, Declaration to Colonial People of the World (Manchester, England, 1945).

- "POLITICAL PARTY ACTIVITY IN GHANA—1947 TO 1957 - Government of Ghana". www.ghana.gov.gh. Retrieved 2018-04-24.

- Daniel Yergin; Joseph Stanislaw (2002). The Commanding Heights: The Battle for the World Economy. Simon and Schuster. p. 66.

- Frank Myers, "Harold Macmillan's" Winds of Change" Speech: A Case Study in the Rhetoric of Policy Change." Rhetoric & Public Affairs 3.4 (2000): 555-575. excerpt

- Philip E. Hemming, "Macmillan and the End of the British Empire in Africa." in R. Aldous and S. Lee, eds., Harold Macmillan and Britain’s World Role (1996) pp. 97-121, excerpt

- James, pp. 618–21.

- Cowan, L. Gray (1964). The Dilemmas of African Independence. New York: Walker & Company, Publishers. pp. 42–55, 105. ASIN B0007DMOJ0.

- Patrick Manning, Francophone Sub-Saharan Africa 1880-1995 (1998) pp 135-63.

- Guy De Lusignan, French-speaking Africa since independence (1969) pp 3-86.

- Rudolph von, Decolonization: the Administration and Future of the Colonies, 1919-1960 (1971), 265-472.

- Tony Smith, "A Comparative Study of French and British Decolonization" Comparative Studies in Society and History 20#1 (1978), pp. 70-102, quoting page 73

- Horne, Alistair (1977). A Savage War of Peace: Algeria 1954–1962. New York: The Viking Press. p. 27.

- J.F.V. Keiger, France and the World since 1870 (Arnold, 2001) p 207.

- Anthony Clayton, The Wars of French Decolonization (1994) p 85

- Martin S. Alexander; et al. (2002). Algerian War and the French Army, 1954–62: Experiences, Images, Testimonies. Palgrave Macmillan UK. p. 6. ISBN 9780230500952.

- Spencer C. Tucker, ed. (2018). The Roots and Consequences of Independence Wars: Conflicts that Changed World History. ABC-CLIO. pp. 355–57. ISBN 9781440855993.CS1 maint: extra text: authors list (link)

- James McDougall, "The Impossible Republic: The Reconquest of Algeria and the Decolonization of France, 1945–1962," Journal of Modern History 89#4 (2017) pp 772–811 excerpt

- "Algeria celebrates 50 years of independence - France keeps mum". RFI. 2012-07-05. Retrieved 2018-05-12.

- Dorothy Shipley White, Black Africa and de Gaulle: From the French Empire to Independence (1979).

- Robert Aldrich, Greater France: A history of French overseas expansion (1996) pp 303–6

- "Mayotte votes to become France's 101st département". The Daily Telegraph. 29 March 2009.

- King, Joan Wucher (1989) [First published 1984]. Historical Dictionary of Egypt. Books of Lasting Value. American University in Cairo Press. pp. 259–260. ISBN 978-977-424-213-7.

- "A/RES/289(IV) - E - A/RES/289(IV)". undocs.org. Retrieved 2020-07-23.

- Robert O. Collins, A History of Modern Sudan

- UN General Assembly Resolution 34/37 and UN General Assembly Resolution 35/19

Further reading

- Birmingham, David (1995). The Decolonization of Africa. Routledge. ISBN 1-85728-540-9.

- Brown, Judith M. and Wm. Roger Louis, eds. The Oxford History of the British Empire: Volume IV: The Twentieth Century (2001) pp 515–73.

- Burton, Antoinette. The Trouble with Empire: Challenges to Modern British Imperialism (2015)

- Chafer, Tony. The end of empire in French West Africa: France's successful decolonization (Bloomsbury Publishing, 2002).

- Chafer, Tony, and Alexander Keese, eds. Francophone Africa at fifty (Oxford UP, 2015).

- Clayton, Anthony. The wars of French decolonization (Routledge, 2014).

- Cooper, Frederick. Decolonization and African society: The labor question in French and British Africa (Cambridge University Press, 1996).

- Gordon, April A. and Donald L. Gordon, Lynne Riener. Understanding Contemporary Africa (London, 1996).

- Hargreaves, John D. Decolonization in Africa (2014).

- Hatch, John. Africa: The Rebirth of Self-Rule (1967)

- Khapoya, Vincent B. The African Experience (1994)

- Louis, William Roger. The transfer of power in Africa: decolonization, 1940-1960 (Yale UP, 1982).

- Louis, Wm Roger, and Ronald Robinson. "The imperialism of decolonization." Journal of Imperial and Commonwealth History 22.3 (1994): 462–511.

- Manthalu, Chikumbutso Herbert, and Yusef Waghid, eds. Education for Decoloniality and Decolonisation in Africa (Springer, 2019).

- Michalopoulos, Stelios; Papaioannou, Elias (2020-03-01). "Historical Legacies and African Development." Journal of Economic Literature. 58 (1): 53–128.

- Mazrui, Ali A. ed. "General History of Africa" vol. VIII, UNESCO, 1993

- Rothermund, Dietmar. The Routledge companion to decolonization (Routledge, 2006), comprehensive global coverage; 365pp

- Strang, David. "From dependency to sovereignty: An event history analysis of decolonization 1870-1987." American Sociological Review (1990): 846–860. online

- von Albertini, Rudolf. Decolonization: the Administration and Future of the Colonies, 1919-1960 (Doubleday, 1971) for the viewpoint from London and Paris.

- White, Nicholas. Decolonization: the British experience since 1945 (Routledge, 2014).

- Winks, Robin, ed. The Oxford History of the British Empire: Volume V: Historiography (2001) ch 29–34, pp 450–557. How historians covered the history

- Wood, Sarah L. "How Empires Make Peripheries: 'Overseas France' in Contemporary History." Contemporary European History (2019): 1-12. online

External links

- Africa: 50 years of independence Radio France Internationale in English

- "Winds of Change or Hot Air? Decolonization and the Salt Water Test" Legal Frontiers International Law Blog