Caesar's Civil War

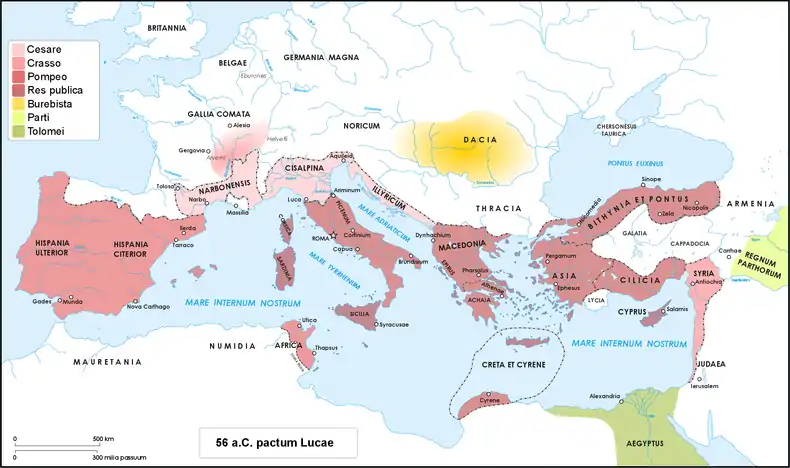

Caesar's Civil War (49–45 BC) was one of the last politico-military conflicts in the Roman Republic before the establishment of the Roman Empire. It began as a series of political and military confrontations, between Julius Caesar (100–44 BC), his political supporters (broadly known as Populares), and his legions, against the Optimates (or Boni), the politically conservative and socially traditionalist faction of the Roman Senate,[3] who were supported by Pompey (106–48 BC) and his legions.[4]

| Caesar's Civil War | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the Roman civil wars | |||||||

-fr.svg.png.webp) Map of the Roman Republic in the mid-1st century BC | |||||||

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

| Caesarians (Populares) | Pompeians (Optimates) | ||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

|

Julius Caesar Mark Antony Gaius Scribonius Curio † Publius Cornelius Sulla Gnaeus Domitius Calvinus Decimus Brutus Albinus Gaius Trebonius Gaius Fabius |

Pompey Titus Labienus † Metellus Scipio † Cato of Utica † Publius Attius Varus † Domitius Ahenobarbus † Marcus Bibulus Lucius Afranius † Marcus Petreius † King Juba of Numidia † Gnaeus Pompeius † Sextus Pompey | ||||||

| Strength | |||||||

| Early 49 BC: 10 legions[1] | Early 49 BC: 15 legions[2] | ||||||

Prior to the war, Caesar had served for eight years in the Gallic Wars. He and Pompey had, along with Marcus Licinius Crassus, established the First Triumvirate, through which they shared power over Rome. Caesar soon emerged as a champion of the common people, and advocated a variety of reforms. The Senate, fearful of Caesar, reduced the number of legions he had,[5] then demanded that he relinquish command of his army. Caesar refused, and instead marched his army on Rome, which no Roman general was permitted to do by law. Pompey fled Rome and organized an army in the south of Italy to meet Caesar.

The war was a four-year-long politico-military struggle, fought in Italy, Illyria, Greece, Egypt, Africa, and Hispania. Pompey defeated Caesar in 48 BC at the Battle of Dyrrhachium, but was himself defeated much more decisively at the Battle of Pharsalus. The Optimates under Marcus Junius Brutus and Cicero surrendered after the battle, while others, including those under Cato the Younger and Metellus Scipio fought on. Pompey fled to Egypt and was killed upon arrival. Scipio was defeated in 46 BC at the Battle of Thapsus in North Africa. He and Cato committed suicide shortly after the battle. The following year, Caesar defeated the last of the Optimates under his former lieutenant Labienus in the Battle of Munda and became Dictator perpetuo (Dictator in perpetuity or Dictator for life) of Rome.[6] The changes to Roman government concomitant to the war mostly eliminated the political traditions of the Roman Republic (509–27 BC) and led to the Roman Empire (27 BC–AD 476).

Background

Caesar's Civil War resulted from the long political subversion of the Roman Government's institutions, which began with the career of Tiberius Gracchus, continuing with the Marian reforms of the legions, the bloody dictatorship of Lucius Cornelius Sulla, and completed by the First Triumvirate over Rome. The political situation is discussed in depth in the ancient histories of Appian and Cassius Dio. It is also covered in the biographies of Plutarch. Julius Caesar's commentaries offer some political details but mainly narrate military manoeuvres of the civil war itself.

The First Triumvirate (so denominated by Cicero), comprising Julius Caesar, Crassus and Pompey, ascended to power with Caesar's election as consul in 59 BC. The First Triumvirate was an unofficial political alliance, the substance of which was Pompey's military might, Caesar's political influence and Crassus's money. The alliance was further consolidated by Pompey's marriage to Julia, the daughter of Caesar, in 59 BC. At the conclusion of Caesar's first consulship, the Senate, rather than granting him a provincial governorship, tasked him with watching over the Roman forests. Specially created by his Senate enemies, that position was meant to occupy him without giving him the command of armies or garnering him wealth and fame.

Caesar, with the help of Pompey and Crassus, evaded the Senate's decrees by legislation passed through the popular assemblies. The acts promoted Caesar to Roman governor of Illyricum and Cisalpine Gaul; Transalpine Gaul (southern France) was added later. The various governorships gave Caesar command of an army of (initially) four legions. The term of his proconsulship, which allowed him immunity from prosecution, was set at five years, rather than the customary one year. His term was later extended for another five years. During the ten years, Caesar used his military forces to conquer Gaul and to invade Britain, which was popular with the people, however his enemies claimed it was without explicit authorization by the Senate.[5]

In 52 BC, at the end of the First Triumvirate, the Roman Senate supported Pompey as sole consul; meanwhile, Caesar had become a military hero and champion of the people. Knowing that he hoped to become consul when his governorship expired, the Senate, politically fearful of him, ordered him to resign his command of his army. In December of 50 BC, Caesar wrote to the Senate that he agreed to resign his military command if Pompey followed suit. Offended, the Senate demanded for him to disband his army immediately, or he would be declared an enemy of the people. That was an illegal political act since he was entitled to keep his army until his term expired.

A secondary reason for Caesar's immediate desire for another consulship was that Caesar's 'imperium' or safety from prosecution was set to expire and his enemies in Rome had senatorial prosecutions awaiting him upon retirement as governor of Illyricum and Gaul. The potential prosecutions were clamored by his enemies for alleged irregularities that occurred in his consulship and war crimes claimed to have been committed during his Gallic campaigns. Moreover, Caesar loyalists, the tribunes Mark Antony and Quintus Cassius Longinus, vetoed the bill and were quickly expelled from the Senate. They then joined Caesar, who had assembled his army, which he asked for military support against the Senate. Agreeing, his army called for action.

In 50 BC, at the expiry of his proconsular term, the Pompey-led Senate ordered Caesar's return to Rome and the disbanding of his army and forbade his standing for election in absentia for a second consulship. That made Caesar think that he would be prosecuted and rendered politically marginal if he entered Rome without consular immunity or his army. To wit, Pompey accused him of insubordination and treason.

Civil War

Crossing the Rubicon

In January, 49 BC, Caesar's opponents in the Senate, led by Lentulus, Cato and Scipio, tried to strip Caesar of his command (provinces and legions) and force him to return to Rome as a private citizen (liable to prosecution). Caesar's allies in the Senate, especially Mark Anthony, Curio, Cassius and Caelius Rufus, tried to defend their patron, but were threatened with violence. On 7 January the Senate passed the consultum ultimum (declaring a state of emergency) and charged the consuls, praetors, tribunes and proconsuls with the defence of the state. That night Anthony, Cassius, Curio and Caelius Rufus fled from Rome and headed north to join Caesar.[7]

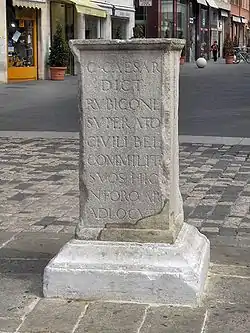

On January 10, 49 BC, commanding the Legio XIII, Caesar crossed the Rubicon River, the boundary between the province of Cisalpine Gaul to the north and Italy proper to the south. As crossing the Rubicon with an army was prohibited, lest a returning general attempt a coup d'etat, that triggered the ensuing civil war between Caesar and Pompey.

The general population, which regarded Caesar as a hero, approved of his actions. The historical records differ about the decisive comment Caesar that made on crossing the Rubicon: one report is Alea iacta est (usually translated as "The die is cast").

Caesar's own account of the Civil War makes no mention of the river crossing but simply states that he marched to Rimini, a town south of the Rubicon, with his army.[8]

March on Rome and the early Hispanian campaign

Within a week of passing the consultum ultimum (declaring a state of emergency and outlawing Caesar) news reached Rome that Caesar had crossed the Rubicon (10 January) and had taken the Italian town of Ariminum (12 January).[9] By January 17 Caesar had taken the next three towns along the Flaminian Way, and that Marcus Anthonius (Mark Anthony) had taken Arretium and controlled the Cassian Way.[9] The Senate, not knowing that Caesar possessed only a single legion, feared the worst and supported Pompey, who declared that Rome could not be defended. He escaped to Capua with those politicians who supported him, the aristocratic Optimates and the regnant consuls. Cicero later characterised Pompey's "outward sign of weakness" as allowing Caesar's consolidation of power.

Despite having retreated into central Italy, Pompey and the Senatorial forces were composed of at least two legions: some 11,500 soldiers and some hastily-levied Italian troops commanded by Lucius Domitius Ahenobarbus. As Caesar progressed southwards, Pompey retreated towards Brundisium, initially ordering Domitius (engaged in raising troops in Etruria) to stop Caesar's movement on Rome from the direction of the Adriatic seaboard.

Belatedly, Pompey requested Domitius to retreat south to rendezvous with Pompey's forces. Domitius ignored Pompey's request believing he outnumbered Caesar three to one. Caesar, however, had been reinforced by two more legions from Gaul (the eighth and the twelfth) and twenty-two cohorts of recruits (recruited by Curio) and in fact outnumbered Domitius five to three. Domitius after being isolated and trapped near Corfinium, was forced to surrender his army of thirty-one cohorts (about three legions) following a brief siege. With deliberate clemency, Caesar released Domitius and the other senators with him and even returned 6,000,000 sesterces that Domitius had had to pay his troops. The thirty-one cohorts, however, were made to swear a new oath of allegiance to Caesar and were eventually sent to Sicily under the command of Asinius Pollio.[10] Caesar now had three veteran legions and fifty-three cohorts of recruits at Corfinium. The Caesarian army in Italy now outnumbered the republicans (8:5) and Pompey knew the peninsula was lost for the time being.

Pompey escaped to Brundisium, there awaiting sea transport for his legions, to Epirus, in the Republic's eastern Greek provinces, expecting his influence to yield money and armies for a maritime blockade of Italy proper. Meanwhile, the aristocrats, including Metellus Scipio and Cato the Younger, joined Pompey there and left a rear guard at Capua.

Caesar pursued Pompey to Brundisium, expecting restoration of their alliance of ten years earlier. Throughout the Great Roman Civil War's early stages, Caesar frequently proposed to Pompey for both generals to sheathe their swords. Pompey refused, legalistically arguing that Caesar was his subordinate and so was obligated to cease campaigning and dismiss his armies before any negotiation. As the Senate's chosen commander and with the backing of at least one of the current consuls, Pompey commanded legitimacy, but Caesar's military crossing of the Rubicon rendered him a de jure enemy of the Senate and the people of Rome. Caesar then tried to trap Pompey in Brundisium by blocking up the harbour mouth with earth moles from either side, joined across the deepest part by a string of rafts, each nine metres square, covered with a causeway of earth and protected with screens and towers. Pompey countered by constructing towers for heavy artillery on a number of merchant ships and used them to destroy the rafts as they were floated in position. Eventually, in March 49 BC, Pompey escaped and fled by sea to Epirus, leaving Caesar in complete command of Italy.[11]

Taking advantage of Pompey's absence from the Italian mainland, Caesar marched west to Hispania. Onroute he started the Siege of Massilia. Within 27 days after setting out he arrived on the Iberian peninsula. At Ilerda he defeated the politically-leaderless Pompeian army, commanded by the legates Lucius Afranius and Marcus Petreius. Afterwards pacifying Roman Hispania.

Returning to Rome in December of 49 BC, Caesar was appointed dictator, with Mark Antony as his Master of the Horse. Caesar kept his dictatorship for eleven days, a tenure sufficient to win him a second term as consul with Publius Servilius Vatia Isauricus as his colleague. Afterwards, Caesar renewed his pursuit of Pompey in Greece.

Greek, Illyrian and African campaigns

From Brundisium, Caesar crossed the Strait of Otranto with seven legions to the Gulf of Valona (not Palaesta in Epirus [modern Palase/Dhermi, Albania], as reported by Lucan),[12] prompting Pompey to consider three courses of action: (i) to make an alliance with the King of Parthia, an erstwhile ally, far to the east; (ii) to invade Italy with his superior navy and/or (iii) to force a decisive battle with Caesar. A Parthian alliance was not feasible since a Roman general fighting Roman legions with foreign troops was craven, and the military risk of an Italian invasion was politically unsavoury because the Italians, who thirty years earlier had rebelled against Rome, might rise against him. Thus, on the advice of his councillors, Pompey decided to engineer a decisive battle.

As it turned out, Pompey would have been obliged to take the third option anyway, as Caesar had forced his hand by pursuing him to Illyria and so on 10 July 48 BC, the two fought in the Battle of Dyrrhachium. With a loss of 1,000 veteran legionaries, Caesar was forced to retreat southwards. Refusing to believe that his army had bested Caesar's legions, Pompey misinterpreted the retreat as a feint into a trap and so did not give chase to deliver the decisive coup de grâce, thus losing the initiative and his chance to conclude the war quickly. Near Pharsalus, Caesar pitched a strategic bivouac. Pompey attacked but, despite his much larger army, was conclusively defeated by Caesar's troops. A major reason for Pompey's defeat was miscommunication among front cavalry horsemen.

Egyptian dynastic struggle

Pompey fled to Egypt, where he was murdered by an officer of King Ptolemy XIII. Caesar pursued the Pompeian army to Alexandria, where he camped and became involved with the Alexandrine Civil War between Ptolemy and his sister, wife and co-regent, Cleopatra VII. Perhaps as a result of Ptolemy's role in Pompey's murder, Caesar sided with Cleopatra and is reported to have wept at the sight of Pompey's head, which was offered to him by Ptolemy's chamberlain, Pothinus, as a gift.

In any event, Caesar was besieged at Alexandria and after Mithridates relieved the city, Caesar defeated Ptolemy's army and installed Cleopatra as ruler with whom he fathered his only known biological son, Ptolemy XV Caesar, better known as "Caesarion". Caesar and Cleopatra never married because Roman law prohibited a marriage with a non-Roman citizen.

War against Pharnaces

After spending the first months of 47 BC in Egypt, Caesar went to Syria and then to Pontus to deal with Pharnaces II, Pompey's client king who had taken advantage of the civil war to attack the Roman-friendly Deiotarus and to make himself the ruler of Colchis and lesser Armenia. At Nicopolis Pharnaces had defeated what little Roman opposition the governor of Asia, Gnaeus Domitius Calvinus, could muster. He had also taken the city of Amisus, which was a Roman ally; made all the boys eunuchs and sold the inhabitants to slave traders. After the show of strength, Pharnaces drew back to pacify his new conquests.

Nevertheless, the extremely-rapid approach of Caesar in person forced Pharnaces to turn his attention back to the Romans. At first, recognising the threat, he made offers of submission with the sole object of gaining time until Caesar's attention fell elsewhere. It was to no avail since Caesar quickly routed Pharnaces at the Battle of Zela (modern Zile in Turkey) with just a small detachment of cavalry. Caesar's victory was so swift and complete that in a letter to a friend in Rome, he famously said of the short war, "Veni, vidi, vici" ("I came, I saw, I conquered"). Indeed, for his Pontic triumph, that may well have been the label displayed above the spoils.

Pharnaces himself fled quickly back to the Bosporus, where he managed to assemble a small force of Scythian and Sarmatian troops with which he was able to gain control of a few cities, but one of his former governors, Asandar, attacked his forces and killed him. The historian Appian states that Pharnaces died in battle, but Cassius Dio says that Pharnaces was captured and then killed.

Later campaign in Africa and the war on Cato

While Caesar had been in Egypt and installed Cleopatra as sole ruler, four of his veteran legions encamped, under the command of Mark Antony. The legions were waiting for their discharges and the bonus pay that Caesar had promised them before the Battle of Pharsalus. As Caesar lingered in Egypt, the situation quickly deteriorated. Antony lost control of the troops, who began looting estates south of the capital. Several delegations of diplomats were dispatched to try to quell the mutiny.

Nothing worked, and the mutineers continued to call for their discharges and back pay. After several months, Caesar finally arrived to address the legions in person. Caesar knew that he needed the legions to deal with Pompey's supporters in North Africa since the latter had mustered 14 legions. Caesar also knew that he did not have the funds to give the soldiers their back pay, much less the money needed to induce them to re-enlist for the North African campaign.

When Caesar approached the speaker's dais, a hush fell over the mutinous soldiers. Most were embarrassed by their role in the mutiny in Caesar's presence. He asked the troops what they wanted with his cold voice. Ashamed to demand money, the men began to call out for their discharge. Caesar bluntly addressed them as "citizens", instead of "soldiers," a tacit indication that they had already discharged themselves by virtue of their disloyalty.

He went on to tell them that they would all be discharged immediately. He said that he would pay them the money that he owed them after he won the North African campaign with other legions. The soldiers were shocked since they had been through 15 years of war with Caesar and they had become fiercely loyal to him in the process. It had never occurred to them that Caesar did not need them.

The soldiers' resistance collapsed. They crowded the dais and begged to be taken to North Africa. Caesar feigned indignation and then allowed himself to be won over. When he announced that he would allow them to join the campaign, a huge cheer arose from the assembled troops. Through that reverse psychology, Caesar re-enlisted four enthusiastic veteran legions to invade North Africa without spending a single sesterce.

Caesar quickly gained a significant victory at the Battle of Thapsus in 46 BC over the forces of Metellus Scipio, Cato the Younger and Juba, who all committed suicide.

Second Hispanian campaign and end of war

Nevertheless, Pompey's sons Gnaeus Pompeius and Sextus Pompeius, together with Titus Labienus, Caesar's former propraetorian legate (legatus propraetore and second in command in the Gallic War, escaped to Hispania. Caesar gave chase and defeated the last remnants of opposition in the Battle of Munda in March 45 BC. Meanwhile, Caesar had been elected to his third and fourth terms as consul in 46 BC (with Marcus Aemilius Lepidus) and 45 BC (sine collega, without a colleague).

Chronology

- 49 BC

- January 1: The Roman Senate receives a proposal from Julius Caesar that he and Pompey should lay down their commands simultaneously. The Senate responds that Caesar must immediately surrender his command.

- January 10: Julius Caesar leads his 13th Legion across the Rubicon, which separates his jurisdiction (Cisalpine Gaul) from that of the Senate (Italy), and thus initiates a civil war.

- February 15: Caesar begins the Siege of Corfinium against Lucius Domitius Ahenobarbus who held the city against Pompey's orders.

- February 21: Corfinium is surrendered to Caesar after a bloodless week in which Ahenobarbus is undermined by his officers.

- February, Pompey's flight to Epirus (in Western Greece) with most of the Senate

- March 9, Caesar's advance against Pompeian forces in Hispania

- April 19, Caesar's siege of Massilia against the Pompeian Lucius Domitius Ahenobarbus, later the siege was conducted by Caesarian Gaius Trebonius

- June, Caesar's arrival in Hispania, where he was able to seize the Pyrenees passes defended by the Pompeian L. Afranius and M. Petreius.

- July 30, Caesar surrounded Afranius and Petreius's army in Ilerda

- August 2, Pompeians in Ilerda surrendered to Caesar

- August 24: Caesar's general Gaius Scribonius Curio, is defeated in North Africa by the Pompeians under Attius Varus and King Juba I of Numidia (whom he defeated earlier in the Battle of Utica, in the Battle of the Bagradas River), and commits suicide.

- September Decimus Junius Brutus Albinus, a Caesarian, defeated the combined Pompeian-Massilian naval forces in the naval Battle of Massilia, while the Caesarian fleet in the Adriatic was defeated near Curicta (Krk)

- September 6, Massilia surrendered to Caesar, coming back from Hispania

- October, Caesar appointed Dictator in Rome; presides over his own election as consul and resigns after eleven days

- 48 BC:

- January 4, Caesar landed at Caesar's Beach in Palasë (Palaeste)[13]

- March, Antony joined Caesar

- July 10: Battle of Dyrrhachium, Julius Caesar barely avoids a catastrophic defeat by Pompey in Macedonia, he retreats to Thessaly.

- August 9: Battle of Pharsalus: Julius Caesar decisively defeats Pompey at Pharsalus and Pompey flees to Egypt.

- September 28, Caesar learned that Pompey was assassinated.

- Siege of Alexandria

- December, Pharnaces, King of Bosporus defeated the Caesarian Gnaeus Domitius Calvinus in the Battle of Nicopolis (or Nikopol)

- December: Battle in Alexandria, Egypt between the forces of Caesar and his ally Cleopatra VII of Egypt and those of rival King Ptolemy XIII of Egypt and Queen Arsinoe IV. The latter two are defeated and flee the city; Cleopatra becomes queen of Egypt. During the battle part of the Library of Alexandria catches fire and is partially burned down.

- Caesar is named Dictator for one year.

- 47 BC

- February: Caesar and his ally Cleopatra defeat the forces of the rival Egyptian Queen Arsinoe IV in the Battle of the Nile, Ptolemy was killed, Caesar then relieved his besieged forces in Alexandria

- May: Caesar defeated Pharnaces II of Pontus, king of the Bosporus in the Battle of Zela. (This is the war that Caesar tersely described veni, vidi, vici.)

- Pharaoh Cleopatra VII of Egypt promotes her younger brother Ptolemy XIV of Egypt to co-ruler.

- August, Caesar quelled a mutiny of his veterans in Rome.

- October, Caesar's invasion of Africa, against Metellus Scipio and Labienus, Caesar's former lieutenant in Gaul

- 46 BC

- January 4: Caesar narrowly escapes defeat by his former second in command Titus Labienus in the Battle of Ruspina; nearly 1/3 of Caesar's army is killed.

- February 6: Caesar defeats the combined army of Pompeian followers and Numidians under Metellus Scipio and Juba in the Battle of Thapsus. Cato commits suicide. Afterwards, he is accorded the office of Dictator for the next ten years.

- November: Caesar leaves for Farther Hispania to deal with a fresh outbreak of resistance.

- Caesar, in his role as Pontifex Maximus, reforms the Roman calendar to create the Julian calendar. The transitional year is extended to 445 days to synchronize the new calendar and the seasonal cycle. The Julian Calendar would remain the standard in the western world for over 1600 years, until superseded by the Gregorian Calendar in 1582.

- Caesar appoints his grandnephew Gaius Octavius his heir.

- 45 BC

- January 1: Julian calendar goes into effect

- March 17: In his last victory, Caesar defeats the Pompeian forces of Titus Labienus and Pompey the younger in the Battle of Munda. Pompey the younger was executed, and Labienus died in battle, but Sextus Pompey escaped to take command of the remnants of the Pompeian fleet.

- The veterans of Caesar's Legions Legio XIII Gemina and Legio X Equestris demobilized. The veterans of the 10th legion would be settled in Narbo, while those of the 13th would be given somewhat better lands in Italia itself.

- Caesar probably writes the Commentaries in this year

- 44 BC

- Julius Caesar is named Dictator perpetuo ("dictator in perpetuity")

- Julius Caesar plans an invasion of the Parthian Empire

- Julius Caesar is assassinated on March 15, the Ides of March.

Aftermath

Caesar was later proclaimed dictator first for ten years and then in perpetuity. The latter arrangement triggered the conspiracy leading to his assassination on the Ides of March in 44 BC. Following this, Antony and Caesar's adopted son Octavius would fight yet another civil war against remnants of the Optimates and Liberatores faction, ultimately resulting in the establishment of the Roman Empire.

References

- Brunt 1971, p. 474.

- Brunt 1971, p. 473.

- https://www.thoughtco.com/ancient-roman-history-optimates-119359

- Kohn, G.C. Dictionary of Wars (1986) p. 374

- https://www.unrv.com/julius-caesar/crossing-the-rubicon.php

- Hornblower, S., Spawforth, A. (eds.) The Oxford Companion to Classical Civilization (1998) pp. 219–24

- Leach, John. Pompey the Great, pp 170–172.

- "C. Julius Caesar, Commentaries on the Civil War, CAESar's COMMENTARIES OF THE CIVIL WAR. , chapter 8".

- Leach, John. Pompey the Great, p. 174.

- John Leach, Pompey the Great, p.183

- John Leach, Pompey the Great, p.185

- Longhurst (2016) "Caesar's Crossing of the Adriatic Countered by a Winter Blockade During the Roman Civil War" The Mariner's Mirror Vol. 102; 132–152

- Caesar, Julius (1976). The civil war. Gardner, Jane F. Harmondsworth: Penguin. ISBN 0-14-044187-5. OCLC 3709815.

Bibliography

- The Commentarii de Bello Civili (Commentaries on the Civil War), events of the Civil War until immediately after Pompey's death in Egypt.

- De Bello Hispaniensi (On the Hispanic War) campaigns in Hispania

- De Bello Africo (On the African War), campaigns in North Africa

- De Bello Alexandrino (On the Alexandrine War), campaign in Alexandria.

- Brunt, P.A. (1971). Italian Manpower 225 B.C.–A.D. 14. Oxford: Clarendon Press. ISBN 0-19-814283-8.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- E.S. Gruen, The Last Generation of the Roman Republic, California U.P. 1974, pp. 449–497. ISBN 0-520-20153-1

- Gelzer, Caesar — Politician and Statesman, Chapter 5. Harvard University Press, 1968.

- Goldsworthy, Adrian (2002). Caesar's Civil War: 49–44 BC. Oxford: Osprey Publishing. ISBN 1-84176-392-6.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Cynthia Damon and William Batstone Caesar's Civil War (Oxford Approaches to Classical Literature, 2006) ISBN 9780195165104

- ed. Cynthia Damon, Brian Breed, and Andreola Rossi Citizens of Discord: Rome and its Civil Wars (Oxford University Press, 2010) ISBN 9780195389579