Camarasauridae

Camarasauridae (meaning "chambered lizards") is a family of neosauropod dinosaurs within the clade Macronaria, the sister group to Titanosauriformes.[5][6] Among sauropods, camarasaurids are small to medium-sized, with relatively short necks. They are visually identifiable by a short skull with large nares, and broad, spatulate teeth filling a thick jaw.[7][8] Based on cervical vertebrae and cervical rib biomechanics, camarasaurids most likely moved their necks in a vertical, rather than horizontal, sweeping motion, in contrast to most diplodocids.[7] Cladistically, they are defined to be all sauropods more closely related to Camarasaurus supremus than to Saltasaurus loricatus.[9]

| Camarasauridae | |

|---|---|

| |

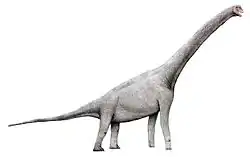

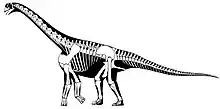

| Skeletal restoration of Camarasaurus supremus. | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Clade: | Dinosauria |

| Clade: | Saurischia |

| Suborder: | †Sauropodomorpha |

| Clade: | †Sauropoda |

| Clade: | †Eusauropoda |

| Clade: | †Neosauropoda |

| Clade: | †Macronaria |

| Clade: | †Camarasauromorpha |

| Clade: | †Camarasauridae Cope, 1877 |

| Type species | |

| †Camarasaurus supremus Cope, 1877a | |

| Species | |

| Synonyms | |

| |

Diagnostic characters

Several skeletal features have been used to characterize the camarasaurids. In the skull, these include an external narial diameter approximately 40% of the long-axis length of the skull, an arched internarial bar, a short muzzle anterior to the nares, and maxillary shelf.[10] In the rest of the axial skeleton, these include flat ventral faces on the cervical vertebrae, a triangular flare to the neural spines of the middle and posterior dorsal vertebrae, and a concave posterior surface to the anterior thoracic ribs, as well as an external haemal canal across the anterior vertebrae of the tail.[10][11] A reduction to two carpals, long metacarpals relative to the radius, and a twisted ischial shaft serve to identify the appendicular skeleton.[7][11]

Palaeobiogeography

Broadly speaking, camarasaurids occupied a distribution limited to the Laurasian continent during the Upper Jurassic.[10] Most currently accepted camarasaurid specimens have been discovered in the Morrison Formation of North America, however some specimens from the African Tendaguru Formation have been speculated to belong to the genus Camarasaurus, and the closely related Lourinhasaurus was found in Portugal.[12][13][14]

References

- Lacovara, Kenneth J.; Ibiricu, L.M.; Lamanna, M.C.; Poole, J.C.; Schroeter, E.R.; Ullmann, P.V.; Voegele, K.K.; Boles, Z.M.; Egerton, V.M.; Harris, J.D.; Martínez, R.D.; Novas, F.E. (September 4, 2014). "A Gigantic, Exceptionally Complete Titanosaurian Sauropod Dinosaur from Southern Patagonia, Argentina". Scientific Reports. 4: 6196. doi:10.1038/srep06196. PMC 5385829. PMID 25186586.

- Mateus, O., & Tschopp E. (2013). Cathetosaurus as a valid sauropod genus and comparisons with Camarasaurus. Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology, Program and Abstracts, 2013. 173.

- Li, K.; Yang, C.-Y.; Liu, J.; Wang, Z.-X. (2010). "[A new sauropod from the Lower Jurassic of Huili, Sichuan, China]". Vertebrata PalAsiatica. 48 (3): 185–202.

- Sánchez-Hernández, B.; Benton, M. J.; Naish, D. (2007). "Dinosaurs and other fossil vertebrates from the Late Jurassic and Early Cretaceous of the Galve area, NE Spain". Palaeogeography, Palaeoclimatology, Palaeoecology. 249 (1): 180–215. doi:10.1016/j.palaeo.2007.01.009.

- Mocho, Pedro; Royo-Torres, Rafael; Ortega, Francisco (2014-02-19). "Phylogenetic reassessment ofLourinhasaurus alenquerensis, a basal Macronaria (Sauropoda) from the Upper Jurassic of Portugal". Zoological Journal of the Linnean Society. 170 (4): 875–916. doi:10.1111/zoj.12113. ISSN 0024-4082.

- 1. Taylor, M. P., & Naish, D. (2005). The phylogenetic taxonomy of Diplodocoidea (Dinosauria: Sauropoda). Museum of Paleontology, University of California, Berkeley.

- 1. Weishampel, D. B., Dodson, P., & Osmólska, H. (Eds.). (1990). The dinosauria. Univ of California Press.

- Coombs, Walter P. (February 1975). "Sauropod habits and habitats". Palaeogeography, Palaeoclimatology, Palaeoecology. 17 (1): 1–33. doi:10.1016/0031-0182(75)90027-9. ISSN 0031-0182.

- TAYLOR, MICHAEL P.; NAISH, DARREN (November 2007). "An Unusual New Neosauropod Dinosaur from the Lower Cretaceous Hastings Beds Group of East Sussex, England". Palaeontology. 50 (6): 1547–1564. doi:10.1111/j.1475-4983.2007.00728.x. ISSN 0031-0239.

- Upchurch, Paul (1995-09-29). "The evolutionary history of sauropod dinosaurs". Phil. Trans. R. Soc. Lond. B. 349 (1330): 365–390. doi:10.1098/rstb.1995.0125. ISSN 0962-8436.

- Wilson, J. A., & Sereno, P. C. (1998). Early evolution and higher-level phylogeny of sauropod dinosaurs. Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology, 18(S2), 1-79.

- FosteR, J. R., & Wedel, M. J. (2014). Haplocanthosaurus (Saurischia: Sauropoda) from the lower Morrison Formation (Upper Jurassic) near Snowmass, Colorado. Volumina Jurassica, 12(2), 197-210.

- Foster, J. R., & Lucas, S. G. (Eds.). (2006). Paleontology and Geology of the Upper Jurassic Morrison Formation: Bulletin 36(Vol. 36). New Mexico Museum of Natural History and Science.

- Raath, J. S. (1987). Sauropod dinosaurs from the Central Zambezi Valley, Zimbabwe, and the age of the Kadzi Formation. South African Journal of Geology, 90(2), 107-119.