Mamenchisaurus

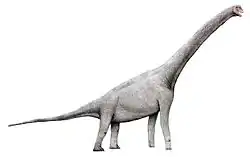

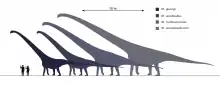

Mamenchisaurus (/mɑːˈmɛntʃiˈsɔːrəs/ mah-MUN-chi-SAWR-əs, or spelling pronunciation /məˌmɛntʃiˈsɔːrəs/) is a genus of sauropod dinosaur including several species, known for their remarkably long necks[3] which made up half the total body length.[4] It is known from numerous species which ranged in time from 160 to 145 million years ago, from the Oxfordian age of late Jurassic Period in China. The largest species, which according to Gregory S. Paul was M. sinocanadorum, may have reached 35 m (115 ft) in length and possibly weighed 50-80 tonnes (55-88 short tons).[5][6]

| Mamenchisaurus | |

|---|---|

| |

| Mounted skeleton of M. sinocanadorum, Japan | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Clade: | Dinosauria |

| Clade: | Saurischia |

| Suborder: | †Sauropodomorpha |

| Clade: | †Sauropoda |

| Clade: | †Eusauropoda |

| Family: | †Mamenchisauridae |

| Genus: | †Mamenchisaurus Young, 1954 |

| Type species | |

| †Mamenchisaurus constructus Young, 1954 | |

| Other species | |

Discovery

Mamenchisaurus was first discovered in 1952 on the construction site of the Yitang Highway in Sichuan, China. The partial skeleton fossil was then studied, and named Mamenchisaurus constructus in 1954, by the renowned Chinese paleontologist Professor C. C. Young. The type specimen had an incomplete neck with 14 vertebrae preserved and none of these were complete. M. constructus has been estimated around 13 m (43 ft) and 15 m (49 ft) in length.[5][7]

Mamenchisaurus means 'Mamenchi lizard', from the Chinese Pinyin mǎ (马 'horse') and mén (门 'gate'), while chi is a transliteration of xī (溪 'stream' or 'brook'), combined with the suffix -saurus (from Greek sauros meaning 'lizard').

It was intended to name the reptile after the place where its fossil was first found—a construction site next to the Mǎmíngxī (马鸣溪) Ferry Crossing by the Jinsha River (金沙江, the westernmost major headwater stream of the Yangtze River), near Yibin (宜宾) in Sichuan Province of China. However, due to an accentual mix-up by Young, the location name Mǎmíngxī (马鸣溪 'horse-neighing brook') was mistaken as Mǎménxī (马门溪 'horse-gate brook').[8] The fact that the first Mamenchisaurus fossil was found as the result of construction work led to Young's naming the type species as Mamenchisaurus constructus.[7]

In 1972, a second species was described, named Mamenchisaurus hochuanensis, with a neck that reached up to 9.3 m (31 ft) in length.[9] This species had a complete neck preserved which contained 19 vertebrae.[10] This was the longest neck known until the description of Supersaurus, based on a single neck vertebra, BYU 9024, with an estimated neck length of about 14 meters (46 feet). Another long-necked sauropod exceeding M. hochuanensis was Sauroposeidon which was discovered in 1994. Based on the Sauroposeidon holotype, which only preserved 4 neck vertebra, its neck was estimated to be between 11.25 and 12 meters (36.9–39.4 feet) long.[11]

In 1993, M. sinocanadorum was described, which consisted of skull material and the first four cervical vertebrae. This species possessed the longest cervical rib of any described sauropod dinosaur, measuring 4.1 m (13.5 ft). This is longer than the longest Sauroposeidon cervical rib, which measures 3.42 m (11.2 ft).[12] Additional remains attributed to this species, but not yet formally described, belong to one of the largest dinosaurs known—the restored skeleton measuring 35 metres (115 ft) in length.[5] It is named in reference to the China-Canada Dinosaur Project.

In 2001, another M. hochuanensis specimen was described. It had skull, pectoral girdle and forelimb material preserved, all of which were missing from the holotype. It was also found with four fused tail vertebra, which have expanded neural arches and taller neural spines, that belong at the tip of the tail. It's thought that these could be a weapon, such as a tail club, or a sensory organ. Other Chinese sauropods, Shunosaurus and Omeisaurus, are also known to have had ’tail clubs’ but they differ in shape to that of M. hochuanensis.[13][14]

Species

- M. anyuensis He, Yang, Cai, Li & Liu, 1996. Approximately 21 meters (69 ft) in length. Known from both the Suining Formation and Penglaizhen Formation.[15] Uranium-lead dating places M. anyuensis at 114.4 Ma in age; as this would make it roughly 30 million years younger than the other Mamenchisaurus species, it is unlikely that M. anyuensis is actually a member of the genus.[1]

- M. constructus Young, 1954: (Type species) The holotype specimen, represented by a partial skeleton that was 13 m (43 ft) long, from the Hantong Formation.

- M. hochuanensis Young & Zhao, 1972: Four partial skeletons. Known from Shaximiao Formation and 22 m (72 ft) in length.[10]

- M. jingyanensis Zhang, Li & Zeng, 1998. Known from Shaximiao Formation and estimated between 20 to 26 metres (66 to 85 ft) in length.[16]

- M. sinocanadorum D. Russell & Zheng, 1993: Partial skull, isolated bones (type), referred, nearly complete skeleton. Known from the upper part of the Shishugou Formation (between 161.2 Ma and 158.7 Ma in age),[1] it may include one of the largest dinosaur specimens known, measuring 35 metres (115 ft) in length.[5][17]

- M. youngi Pi, Ouyang & Ye, 1996:[18] Mamenchisaurus youngi (pronunciation YOUNG-eye) was unearthed in Xinmin County, Zigong City in Sichuan Province, China, in 1989.[19] The species was named in honour of Young. It was a very complete and articulated specimen preserving all the vertebra from the head up until the 8th tail vertebra. It had 18 neck vertebra. At 16 meters (52 ft) long with a 6.5-meter (21 ft) neck, is relatively small among various species of Mamenchisaurus.

Classification

The cladogram below shows a possible phylogenetic position:[20]

| Sauropoda |

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

References

- Wang, J.; Norell, M. A.; Pei, R.; Ye, Y.; Chang, S.-C (2019). "Surprisingly young age for the mamenchisaurid sauropods in South China". Cretaceous Research. 104: 104176. doi:10.1016/j.cretres.2019.07.006.

- Fang, X.; Zhao; Lu, L.; Cheng, Z. (2004). "Discovery of Late Jurassic Mamenchisaurus in Yunnan, southwestern China". Geological Bulletin of China. 23 (9–10): 1005–1011.

- Sues, Hans-Dieter (1997). "Sauropods". In James Orville Farlow; M. K. Brett-Surman (eds.). The Complete Dinosaur. Bloomington: Indiana University Press. pp. 274. ISBN 0-253-33349-0.

- Norman, David B. (2004). "Dinosaur Systematics". In Weishampel, D.B.; Dodson, P.; Osmólska, H. (eds.). The Dinosauria (2nd ed.). Berkeley: University of California Press. pp. 318. ISBN 0-520-24209-2.

- Paul, G.S. (2010). The Princeton Field Guide to Dinosaurs, Princeton University Press.

- Paul, Gregory S. (2019). "Determining the largest known land animal: A critical comparison of differing methods for restoring the volume and mass of extinct animals" (PDF). Annals of the Carnegie Museum. 85 (4): 335–358. doi:10.2992/007.085.0403. S2CID 210840060.

- Young, C.C. (1954), On a new sauropod from Yiping, Szechuan, China. sinica, III(4), 481-514.

- Origin of the Mamenchisaurus name Archived 2007-09-27 at the Wayback Machine (in Chinese), Beijing Museum of Natural History website

- Paul, G.S. (1988). "The brachiosaur giants of the Morrison and Tendaguru with a description of a new subgenus, Giraffatitan, and a comparison of the world's largest dinosaurs". Hunteria, 2(3): 1–14.

- Young, C.C., and Zhao, X.-J. (1972). "Mamenchisaurus hochuanensis sp. nov." Institute of Vertebrate Paleontology and Paleoanthropology Monographs, A, 8:1-30.

- Wedel, M.J., and Cifelli, R.L. (2005). "Sauroposeidon: Oklahoma’s native giant." Oklahoma Geology Notes, 65(2): 40-57.

- "Osteology, paleobiology, and relationships of the sauropod dinosaur Sauroposeidon", by Mathew J. Wedel, Richard L. Cifelli, and R. Kent Sanders (Acta Palaeontologica Polonica 45, pages 343–388, 2000).

- Ye, Y.; Ouyang, H.; Fu, Q.-M. (2001). "New material of Mamenchisaurus hochuanensis from Ziging China". Vertebrata PalAsiatica. 39 (4): 266–271.

- Xing, L; Ye, Y; Shu, C; Peng, G; You, H (2009). "Structure, orientation and finite element analysis of the tail club of Mamenchisaurus hochuanensis". Acta Geologica Sinica (English Edition). 83 (6): 1031–1040. doi:10.1111/j.1755-6724.2009.00134.x.

- He, Xinlu; Yang, Suihua; Cai, Kaiji; Li, kui; Liu, Zongwen (1996). "A new species of sauropod, Mamenchisaurus anyuensis sp. nov." (PDF). Papers on Geosciences Contributed to the 30th Geological Congress: 83–86.

- Zhang, Yihong; Li, kui; Zeng, Qinghua (1998). "'A new species of sauropod from the Late Jurassic of the Sichuan Basin (Mamenchisaurus jingyanensis sp. nov.)'". Journal of the Chengdu University of Technology. 25 (1): 61–68.

- Russell, D.A., Zheng, Z. (1993). "A large mamenchisaurid from the Junggar Basin, Xinjiang, People Republic of China." Canadian Journal of Earth Sciences, (30): 2082-2095.

- PI, L., OU, Y. and YE, Y. 1996. A new species of sauropod from Zigong, Sichuan, Mamenchisaurus youngi. 87–91. In DEPARTMENT OF SPATIAL PLANNING AND REGIONAL ECONOMY (ed.), Publication in Geoscience Contributed to the 30th International Geological Congress. China Economic Publishing House, Beijing.

- Ouyang, H. and Ye, Y. 2002. The First Mamenchisaurian Skeleton with Complete Skull: Mamenchisaurus youngi (in Chinese with English summary). 111 pp + 20 plates. Sichuan Science and Technology Press, Chengdu.

- J.A. Wilson, 2002, "Sauropod dinosaur phylogeny: critique and cladistic analysis", Zoological Journal of the Linnean Society 136: 217-276

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Mamenchisaurus. |

- Dinosaur.net.cn (in Chinese and English)