Canine parvovirus

Canine parvovirus (also referred to as CPV, CPV2, or parvo) is a contagious virus mainly affecting dogs. CPV is highly contagious and is spread from dog to dog by direct or indirect contact with their feces. Vaccines can prevent this infection, but mortality can reach 91% in untreated cases. Treatment often involves veterinary hospitalization. Canine parvovirus may infect other mammals including foxes, wolves, cats, and skunks.[1] Felines are susceptible to panleukopenia, a different strain of parvovirus.[2]

| Canine parvovirus | |

|---|---|

| |

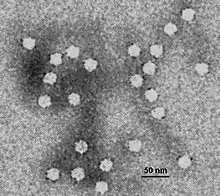

| Electron micrograph of canine parvovirus | |

| Virus classification | |

| (unranked): | Virus |

| Realm: | Monodnaviria |

| Kingdom: | Shotokuvirae |

| Phylum: | Cossaviricota |

| Class: | Quintoviricetes |

| Order: | Piccovirales |

| Family: | Parvoviridae |

| Genus: | Protoparvovirus |

| Species: | Carnivore protoparvovirus 1 |

| Virus: | Canine parvovirus |

Signs

Dogs that develop the disease show signs of the illness within three to seven days. The signs may include lethargy, vomiting, fever, and diarrhea (usually bloody). Generally, the first sign of CPV is lethargy. Secondary signs are loss of weight and appetite or diarrhea followed by vomiting. Diarrhea and vomiting result in dehydration that upsets the electrolyte balance and this may affect the dog critically. Secondary infections occur as a result of the weakened immune system. Because the normal intestinal lining is also compromised, blood and protein leak into the intestines, leading to anemia and loss of protein, and endotoxins escape into the bloodstream, causing endotoxemia. Dogs have a distinctive odor in the later stages of the infection. The white blood cell level falls, further weakening the dog. Any or all of these factors can lead to shock and death. Younger animals have worse survival rates.[3]

Diagnosis

Diagnosis is made through detection of CPV2 in the feces by either an ELISA or a hemagglutination test, or by electron microscopy. PCR has become available to diagnose CPV2, and can be used later in the disease when potentially less virus is being shed in the feces that may not be detectable by ELISA.[4] Clinically, the intestinal form of the infection can sometimes be confused with coronavirus or other forms of enteritis. Parvovirus, however, is more serious and the presence of bloody diarrhea, a low white blood cell count, and necrosis of the intestinal lining also point more towards parvovirus, especially in an unvaccinated dog. The cardiac form is typically easier to diagnose because the symptoms are distinct.[5]

Treatment

Survival rate depends on how quickly CPV is diagnosed, the age of the dog, and how aggressive the treatment is. There is no approved treatment, and the current standard of care is supportive care, involving extensive hospitalization, due to severe dehydration and potential damage to the intestines and bone marrow. A CPV test should be given as early as possible if CPV is suspected in order to begin early treatment and increase survival rate if the disease is found.

Supportive care ideally also consists of crystalloid IV fluids and/or colloids (e.g., Hetastarch), antinausea injections (antiemetics) such as maropitant, metoclopramide, dolasetron, ondansetron and prochlorperazine, and broad-spectrum antibiotic injections such as cefazolin/enrofloxacin, ampicillin/enrofloxacin, metronidazole, timentin, or enrofloxacin.[6] IV fluids are administered and antinausea and antibiotic injections are given subcutaneously, intramuscularly, or intravenously. The fluids are typically a mix of a sterile, balanced electrolyte solution, with an appropriate amount of B-complex vitamins, dextrose, and potassium chloride. Analgesic medications can be used to counteract the intestinal discomfort caused by frequent bouts of diarrhea; however, the use of opioid analgesics can result in secondary ileus and decreased motility.

In addition to fluids given to achieve adequate rehydration, each time the puppy vomits or has diarrhea in a significant quantity, an equal amount of fluid is administered intravenously. The fluid requirements of a patient are determined by the animal's body weight, weight changes over time, degree of dehydration at presentation, and surface area.

A blood plasma transfusion from a donor dog that has already survived CPV is sometimes used to provide passive immunity to the sick dog. Some veterinarians keep these dogs on site, or have frozen serum available. There have been no controlled studies regarding this treatment.[6] Additionally, fresh frozen plasma and human albumin transfusions can help replace the extreme protein losses seen in severe cases and help assure adequate tissue healing. However, this is controversial with the availability of safer colloids such as Hetastarch, as it will also increase the colloid osmotic pressure without the ill effect of predisposing that canine patient to future transfusion reaction.

Once the dog can keep fluids down, the IV fluids are gradually discontinued, and very bland food slowly introduced. Oral antibiotics are administered for a number of days depending on the white blood cell count and the patient's ability to fight off secondary infection. A puppy with minimal symptoms can recover in two or three days if the IV fluids are begun as soon as symptoms are noticed and the CPV test confirms the diagnosis. If more severe, depending on treatment, puppies can remain ill from five days up to two weeks. However, even with hospitalization, there is no guarantee that the dog will be cured and survive.

Treatments in Development

Kindred Biosciences is developing a monoclonal antibody for parvovirus. The company announced in August of 2019 that they had 100% efficacy in the treatment and prophylaxis of parvovirus in a pilot efficacy study, and announced in September of 2020 that they had 100% efficacy in the prophylaxis of parvovirus in a pivotal efficacy study.[7]

Unconventional treatments

There have been anecdotal reports of oseltamivir (Tamiflu) reducing disease severity and hospitalization time in canine parvovirus infection. The drug may limit the ability of the virus to invade the crypt cells of the small intestine and decrease gastrointestinal bacteria colonization and toxin production. However, due to the viral DNA replication pattern of parvovirus and the mechanism of action of oseltamivir, this medication has not shown to improve survival rates or shorten hospitalization stay.[8] Lastly, recombinant feline interferon omega (rFeIFN-ω), produced in silkworm larvae using a baculovirus vector, has been demonstrated by multiple studies to be an effective treatment. However, this therapy is not currently approved in the United States.[9][10][11][12]

An unpublished 2012 study from Colorado State University showed good results with an intensive at-home treatment using maropitant (Cerenia) and Convenia (a long acting antibiotic injection), two drugs released by Zoetis (formerly Pfizer). This treatment was based on outpatient care, and would cost $200 to $300, a fraction of the $1,500 to $3,000 that inpatient care cost. However, the more-effective care is intravenous (IV) fluid therapy. In the CSU study, survival rate for the new treatment group was 85%, compared to the 90% survival for the conventional inpatient treatment.[13] Note that the outpatient dogs received initial intravenous fluid resuscitation, and had aggressive subcutaneous fluid therapy and daily monitoring by a veterinarian. The dogs have to be taken to the vet every 12 hours for successful treatment and recovery of the dog.

History

Parvovirus CPV2 is a relatively new disease that appeared in the late 1970s. It was first recognized in 1978 and spread worldwide in one to two years.[14] The virus is very similar to feline panleukopenia (also a parvovirus); they are 98% identical, differing only in two amino acids in the viral capsid protein VP2.[15] It is also highly similar to mink enteritis virus (MEV), and the parvoviruses of raccoons and foxes.[5] It is possible that CPV2 is a mutant of an unidentified parvovirus (similar to feline parvovirus (FPV)) of some wild carnivore.[16] CPV2 was thought to only cause diseases in canines,[5] but newer evidence suggest pathogenicity in cats too.[17][18]

Variants

There are two types of canine parvovirus called canine minute virus (CPV1) and CPV2. CPV2 causes the most serious disease and affects domesticated dogs and wild canids. There are variants of CPV2 called CPV-2a and CPV-2b, identified in 1979 and 1984 respectively.[16] Most of canine parvovirus infection are believed to be caused by these two strains, which have replaced the original strain, and the present day virus is different from the one originally discovered, although they are indistinguishable by most routine tests.[19][20] An additional variant is CPV-2c, a Glu-426 mutant, and was discovered in Italy, Vietnam, and Spain.[21] The antigenic patterns of 2a and 2b are quite similar to the original CPV2. Variant 2c however has a unique pattern of antigenicity.[22] This has led to claims of ineffective vaccination of dogs,[23] but studies have shown that the existing CPV vaccines based on CPV-2b provide adequate levels of protection against CPV-2c. A strain of CPV-2b (strain FP84) has been shown to cause disease in a small percentage of domestic cats, although vaccination for FPV seems to be protective.[20] With severe disease, dogs can die within 48 to 72 hours without treatment by fluids. In the more common, less severe form, mortality is about 10 percent.[15] Certain breeds, such as Rottweilers, Doberman Pinschers, and Pit bull terriers as well as other black and tan colored dogs may be more susceptible to CPV2.[24] Along with age and breed, factors such as a stressful environment, concurrent infections with bacteria, parasites, and canine coronavirus increase a dog's risk of severe infection.[3] Dogs infected with parvovirus usually die from the dehydration it causes or secondary infection rather than the virus itself.

The variants of CPV-2 are defined by surface protein (VP capsid) features. This classification does not correlate well with phylogenies built from other parts of the viral genome, such as the NS1 protein.[25]

Intestinal form

Dogs become infected through oral contact with CPV2 in feces, infected soil, or fomites that carry the virus. Following ingestion, the virus replicates in the lymphoid tissue in the throat, and then spreads to the bloodstream. From there, the virus attacks rapidly dividing cells, notably those in the lymph nodes, intestinal crypts, and the bone marrow. There is depletion of lymphocytes in lymph nodes and necrosis and destruction of the intestinal crypts.[26] Anaerobic bacteria that normally reside in the intestines can then cross into the bloodstream, a process known as translocation, with bacteremia leading to sepsis. The most common bacteria involved in severe cases are Clostridium, Campylobacter and Salmonella species. This can lead to a syndrome known as systemic inflammatory response syndrome (SIRS). SIRS leads to a range of complications such as hypercoagulability of the blood, endotoxaemia and acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS). Bacterial myocarditis has also been reported secondarily to sepsis.[4] Dogs with CPV are at risk of intussusception, a condition where part of the intestine prolapses into another part.[3] Three to four days following infection, the virus is shed in the feces for up to three weeks, and the dog may remain an asymptomatic carrier and shed the virus periodically.[27] The virus is usually more deadly if the host is concurrently infested with worms or other intestinal parasites.

Cardiac form

This form is less common and affects puppies infected in the uterus or shortly after birth until about 8 weeks of age.[3] The virus attacks the heart muscle and the puppy often dies suddenly or after a brief period of breathing difficulty due to pulmonary edema. On the microscopic level, there are many points of necrosis of the heart muscle that are associated with mononuclear cellular infiltration. The formation of excess fibrous tissue (fibrosis) is often evident in surviving dogs. Myofibers are the site of viral replication within cells.[5] The disease may or may not be accompanied with the signs and symptoms of the intestinal form. However, this form is now rarely seen due to widespread vaccination of breeding dogs.[27]

Even less frequently, the disease may also lead to a generalized infection in neonates and cause lesions and viral replication and attack in other tissues other than the gastrointestinal tissues and heart, but also brain, liver, lungs, kidneys, and adrenal cortex. The lining of the blood vessels are also severely affected, which lead the lesions in this region to hemorrhage.[5]

Infection of the fetus

This type of infection can occur when a pregnant female dog is infected with CPV2. The adult may develop immunity with little or no clinical signs of disease. The virus may have already crossed the placenta to infect the fetus. This can lead to several abnormalities. In mild to moderate cases the pups can be born with neurological abnormalities such as cerebellar hypoplasia.[28]

Virology

CPV2 is a non-enveloped single-stranded DNA virus in the Parvoviridae family. The name comes from the Latin parvus, meaning small, as the virus is only 20 to 26 nm in diameter. It has an icosahedral symmetry. The genome is about 5000 nucleotides long.[29] CPV2 continues to evolve, and the success of new strains seems to depend on extending the range of hosts affected and improved binding to its receptor, the canine transferrin receptor.[30] CPV2 has a high rate of evolution, possibly due to a rate of nucleotide substitution that is more like RNA viruses such as Influenzavirus A.[31] In contrast, FPV seems to evolve only through random genetic drift.[32]

CPV2 affects dogs, wolves, foxes, and other canids. CPV2a and CPV2b have been isolated from a small percentage of symptomatic cats and is more common than feline panleukopenia in big cats.[33]

Previously it has been thought that the virus does not undergo cross species infection. However studies in Vietnam have shown that CPV2 can undergo minor antigenic shift and natural mutation to infect felids. Analyses of feline parvovirus (FPV) isolates in Vietnam and Taiwan revealed that more than 80% of the isolates were of the canine parvovirus type, rather than feline panleukopenia virus (FPLV).[34] CPV2 may spread to cats easier than dogs and undergo faster rates of mutation within that species.

Prevention and decontamination

Prevention is the only way to ensure that a puppy or dog remains healthy because the disease is extremely virulent and contagious. Appropriate vaccination should be performed starting at 7–8 weeks of age, with a booster given every 3–4 weeks until at least 16 weeks of age. Pregnant mothers should not be vaccinated as it will abort the puppies and could make the mother extremely sick. The virus is extremely hardy and has been found to survive in feces and other organic material such as soil for up to 1 year. It survives extremely low and high temperatures. The only household disinfectant that kills the virus is bleach.[3] The dilute bleach solution needs to be in a 1:10 ratio to disinfect and kill parvovirus.

Puppies are generally vaccinated in a series of doses, extending from the earliest time that the immunity derived from the mother wears off until after that passive immunity is definitely gone.[35] Older puppies (16 weeks or older) are given 3 vaccinations 3 to 4 weeks apart.[24] The duration of immunity of vaccines for CPV2 has been tested for all major vaccine manufacturers in the United States and has been found to be at least three years after the initial puppy series and a booster 1 year later.[36]

A dog that successfully recovers from CPV2 generally remains contagious for up to three weeks, but it is possible they may remain contagious for up to six. Ongoing infection risk is primarily from fecal contamination of the environment due to the virus's ability to survive many months in the environment. Neighbours and family members with dogs should be notified of infected animals so that they can ensure that their dogs are vaccinated or tested for immunity. A modified live vaccine may confer protection in 3 to 5 days; the contagious individual should remain in quarantine until other animals are protected.[37]

See also

References

- Holmes, Edward C.; Parrish, Colin R.; Dubovi, Edward J.; Shearn-Bochsler, Valerie I.; Gerhold, Richard W.; Brown, Justin D.; Fox, Karen A.; Kohler, Dennis J.; Allison, Andrew B. (2013-02-15). "Frequent Cross-Species Transmission of Parvoviruses among Diverse Carnivore Hosts". Journal of Virology. 87 (4): 2342–2347. doi:10.1128/JVI.02428-12. ISSN 0022-538X. PMC 3571474. PMID 23221559.

- Hartmann, Katrin; Steutzer, Bianca (August 2014). "Feline parvovirus infection and associated diseases". Pubmed. Retrieved 17 September 2020.

- Ettinger, Stephen J.; Feldman, Edward C. (1995). Textbook of Veterinary Internal Medicine (4th ed.). W.B. Saunders Company. ISBN 978-0-7216-6795-9.

- Silverstein, Deborah C. (2003). Intensive Care Treatment of Severe Parvovirus Enteritis. International Veterinary Emergency and Critical Care Symposium 2003.

- Jones, T.C.; Hunt, R.D.; King, W. (1997). Veterinary Pathology. Blackwell Publishing.

- Macintire, Douglass K. (2008). "Treatment of Severe Parvoviral Enteritis". Proceedings of the CVC Veterinary Conference, Kansas City. Retrieved 2011-08-10.

- https://www.veterinarypracticenews.com/canine-parvovirus-treatment-may-be-in-the-works/

- Savigny, M. R.; MacIntire, D. K. (2010). "Use of oseltamivir in the treatment of canine parvoviral enteritis". Journal of Veterinary Emergency and Critical Care (San Antonio, Tex. : 2001). 20 (1): 132–42. doi:10.1111/j.1476-4431.2009.00404.x. PMID 20230441.

- Ishiwata K, Minagawa T, Kajimoto T (1998). "Clinical effects of the recombinant feline interferon-ω on experimental parvovirus infection in beagle dogs". J. Vet. Med. Sci. 60 (8): 911–7. doi:10.1292/jvms.60.911. PMID 9764403.

- Martin V, Najbar W, Gueguen S, Grousson D, Eun HM, Lebreux B, Aubert A (2002). "Treatment of canine parvoviral enteritis with interferon-omega in a placebo-controlled challenge trial". Vet. Microbiol. 89 (2–3): 115–127. doi:10.1016/S0378-1135(02)00173-6. PMID 12243889.

- De Mari K, Maynard L, Eun HM, Lebreux B (2003). "Treatment of canine parvoviral enteritis with interferon-omega in a placebo-controlled field trial". Vet. Rec. 152 (4): 105–8. doi:10.1136/vr.152.4.105. PMID 12572939.

- Kuwabara M, Nariai Y, Horiuchi Y, Nakajima Y, Yamaguchi Y, Horioka I, Kawanabe M, Kubo Y, Yukawa M, Sakai T (2006). "Immunological effects of recombinant feline interferon-ω (KT80) administration in the dog". Microbiol. Immunol. 50 (8): 637–641. doi:10.1111/j.1348-0421.2006.tb03828.x. PMID 16924149.

- "New Protocol Gives Parvo Puppies a Fighting Chance When Owners Can't Afford Hospitalization". College of Veterinary Medicine & Biomedical Sciences, Colorado State University. Archived from the original on 17 October 2012. Retrieved 29 September 2013.

- Carmichael L (2005). "An annotated historical account of canine parvovirus". J. Vet. Med. B Infect. Dis. Vet. Public Health. 52 (7–8): 303–11. doi:10.1111/j.1439-0450.2005.00868.x. PMID 16316389.

- Carter, G.R.; Wise, D.J. (2004). "Parvoviridae". A Concise Review of Veterinary Virology. IVIS. Retrieved 2014-01-30.

- Shackelton LA, Parrish CR, Truyen U, Holmes EC (2005). "High rate of viral evolution associated with the emergence of carnivore parvovirus". Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 102 (2): 379–384. Bibcode:2005PNAS..102..379S. doi:10.1073/pnas.0406765102. PMC 544290. PMID 15626758.

- Marks SL (2016). "Rational Approach to Diagnosing and Managing Infectious Causes of Diarrhea in Kittens". August's Consultations in Feline Internal Medicine, Volume 7. pp. 1–22. doi:10.1016/B978-0-323-22652-3.00001-3. ISBN 978-0-323-22652-3.

- Ikeda Y, Nakamura K, Miyazawa T, Takahashi E, Mochizuki M (April 2002). "Feline host range of canine parvovirus: recent emergence of new antigenic types in cats". Emerging Infectious Diseases. 8 (4): 341–6. doi:10.3201/eid0804.010228. PMC 2730235. PMID 11971764.

- Macintire, Douglass K. (2006). "Treatment of Parvoviral Enteritis". Proceedings of the Western Veterinary Conference. Retrieved 2007-06-09.

- Gamoh K, Senda M, Inoue Y, Itoh O (2005). "Efficacy of an inactivated feline panleucopenia virus vaccine against a canine parvovirus isolated from a domestic cat". Vet. Rec. 157 (10): 285–7. doi:10.1136/vr.157.10.285. PMID 16157570.

- Decaro N, Martella V, Desario C, Bellacicco A, Camero M, Manna L, d'Aloja D, Buonavoglia C (2006). "First detection of canine parvovirus type 2c in pups with haemorrhagic enteritis in Spain". J. Vet. Med. B Infect. Dis. Vet. Public Health. 53 (10): 468–72. doi:10.1111/j.1439-0450.2006.00974.x. PMC 7165763. PMID 17123424.

- Cavalli, Alessandra; Vito Martella; Costantina Desario; Michele Camero; Anna Lucia Bellacicco; Pasquale De Palo; Nicola Decaro; Gabriella Elia; Canio Buonavoglia (March 2008). "Evaluation of the Antigenic Relationships among Canine Parvovirus Type 2 Variants". Clin Vaccine Immunol. 15 (3): 534–9. doi:10.1128/CVI.00444-07. PMC 2268271. PMID 18160619.

- TV.com, Wood (August 23, 2008). "Virus killing Kent County dogs". WoodTV.com-Grand Rapids. Archived from the original on 2008-08-27. Retrieved 2011-08-10.

- Nelson, Richard W.; Couto, C. Guillermo (1998). Small Animal Internal Medicine (2nd ed.). Mosby. ISBN 978-0-8151-6351-0.

- Mira, F; Canuti, M; Purpari, G; Cannella, V; Di Bella, S; Occhiogrosso, L; Schirò, G; Chiaramonte, G; Barreca, S; Pisano, P; Lastra, A; Decaro, N; Guercio, A (29 March 2019). "Molecular Characterization and Evolutionary Analyses of Carnivore Protoparvovirus 1 NS1 Gene". Viruses. 11 (4). doi:10.3390/v11040308. PMID 30934948.

- Lobetti, Remo (2003). "Canine Parvovirus and Distemper". Proceedings of the 28th World Congress of the World Small Animal Veterinary Association. Retrieved 2007-04-22.

- "Canine Parvovirus". The Merck Veterinary Manual. 2006. Archived from the original on 2006-05-03. Retrieved 2007-04-22.

- Schatzberg, S.J.; N.J. Haley; S.C. Bar; A. deLahunta; J.N. Kornegay; N.J.H. Sharp (2002). Polymerase Chain Reaction Amplification Of Parvoviral DNA From The Brains Of Dogs And Cats With Cerebellar Hypoplasia. ACVIM 2002. Cornell University Hospital for Animals, Ithaca, NY; College of Vet Med, University of Missouri, Columbia, MO; Vancouver, British Columbia, Canada.

- ICTVdB Management (2006). 00.050.1.01. Parvovirus. In: ICTVdB—The Universal Virus Database, version 4. Büchen-Osmond, C. (Ed), Columbia University, New York, USA

- Truyen U (2006). "Evolution of canine parvovirus—a need for new vaccines?". Vet. Microbiol. 117 (1): 9–13. doi:10.1016/j.vetmic.2006.04.003. PMID 16765539.

- Shackelton L, Parrish C, Truyen U, Holmes E (2005). "High rate of viral evolution associated with the emergence of carnivore parvovirus". Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 102 (2): 379–84. Bibcode:2005PNAS..102..379S. doi:10.1073/pnas.0406765102. PMC 544290. PMID 15626758.

- Horiuchi M, Yamaguchi Y, Gojobori T, Mochizuki M, Nagasawa H, Toyoda Y, Ishiguro N, Shinagawa M (1998). "Differences in the evolutionary pattern of feline panleukopenia virus and canine parvovirus". Virology. 249 (2): 440–52. doi:10.1006/viro.1998.9335. PMID 9791034.

- Recent Advances in Canine Infectious Diseases, Carmichael L. (Ed.) International Veterinary Information Service, Ithaca NY (www.ivis.org), 2000; A0106.0100

- Ikeda, Y; Mochizuki M; Naito R; Nakamura K; Miyazawa T; Mikami T; Takahashi E (2000-12-05). "Predominance of canine parvovirus (CPV) in unvaccinated cat populations and emergence of new antigenic types of CPVs in cats". Virology. 278 (1): 13–9. doi:10.1006/viro.2000.0653. PMID 11112475.

- Oh J, Ha G, Cho Y, Kim M, An D, Hwang K, Lim Y, Park B, Kang B, Song D (2006). "One-Step Immunochromatography Assay Kit for Detecting Antibodies to Canine Parvovirus". Clin. Vaccine Immunol. 13 (4): 520–4. doi:10.1128/CVI.13.4.520-524.2006. PMC 1459639. PMID 16603622.

- Schultz R (2006). "Duration of immunity for canine and feline vaccines: a review". Vet. Microbiol. 117 (1): 75–9. doi:10.1016/j.vetmic.2006.04.013. PMID 16707236.

- "Resources – Koret Shelter Medicine Program". UC DAVIS. UC DAVIS. Retrieved 2018-10-25.