Prince Rupert, British Columbia

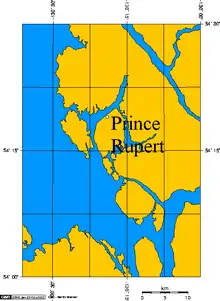

Prince Rupert is a port city in the province of British Columbia, Canada. Its location is on Kaien Island near the Alaskan panhandle. This port city is the land, air, and water transportation hub of British Columbia's North Coast, and has a population of 12,220 people as of 2016.[2]

Prince Rupert | |

|---|---|

| City of Prince Rupert | |

Aerial view of Prince Rupert | |

Coat of arms | |

Prince Rupert Location of Prince Rupert in British Columbia  Prince Rupert Prince Rupert (Canada) | |

| Coordinates: 54°18′44″N 130°19′38″W | |

| Country | |

| Province | |

| Indigenous territories | Tsimshian, unceded |

| Regional District | Skeena-Queen Charlotte |

| Incorporated | March 10, 1910 |

| Named for | Prince Rupert of the Rhine |

| Government | |

| • Mayor | Lee Brain[1] |

| • Governing Body | Prince Rupert City Council |

| • MP | Taylor Bachrach (NDP) |

| • MLA | Jennifer Rice (NDP) |

| Area | |

| • City | 54.93 km2 (21.21 sq mi) |

| • Metro | 222.94 km2 (86.08 sq mi) |

| Elevation | 40 m (130 ft) |

| Population (2011)[2] | |

| • City | 12,220 |

| • Density | 227.7/km2 (590/sq mi) |

| • Metro | 13,052 |

| • Metro density | 58.5/km2 (152/sq mi) |

| Time zone | UTC-8 (Pacific Time Zone) |

| • Summer (DST) | UTC-7 (Pacific Daylight Time) |

| Forward sortation area | V8J |

| Area code(s) | 250 / 778 / 236 |

| Highways | |

| Website | Prince Rupert.ca |

History

Coast Tsimshian occupation of the Prince Rupert Harbour area spans at least 5,000 years. About 1500 B.C. there was a significant population increase, associated with larger villages and house construction. The early 1830s saw a loss of Coast Tsimshian influence in the Prince Rupert Harbour area.[3]

Founding

Prince Rupert replaced Port Simpson as the choice for the Grand Trunk Pacific Railway (GTP) western terminus.[4] It also replaced Port Essington, 29 kilometres (18 mi) away on the southern bank of the Skeena River, as the business centre for the North Coast .

The GTP purchased the 14,000-acre First Nations reserve, and received a 10,000-acre grant from the BC government. A post office was established on November 23, 1906.[5] Surveys and clearing, that commenced in that year, preceded the laying out of the 2,000-acre town site. A $200,000 provincial grant financed plank sidewalks, roads, sewers and water mains.[6] Kaien Island, which comprised damp muskeg overlaying a solid rock foothill, proved expensive both for developing the land for railway and town use.[7]

By 1909, the town possessed 4 grocery, 2 hardware, 2 men's clothing, a furniture, and several fruit and cigar stores, a wholesale drygoods outlet, a wholesale/retail butcher, 2 banks, the GTP hotel and annex, and numerous lodging houses and restaurants.[8] The first lot sales that year created a bidding war.[9]

Prince Rupert was incorporated on March 10, 1910. Although he never visited Canada, it was named after Prince Rupert of the Rhine, the first Governor of the Hudson's Bay Company, as the result of a nation-wide competition held by the Grand Trunk Railway, the prize for which was $250.[10][11]

With the collapse of the real estate boom in 1912, and World War I, much of the company's land remained unsold. Charles Melville Hays, president of the GTP, whose business plan made little sense, was primarily responsible for the bankruptcy of the company, and the establishment of a town that would take decades to achieve even a small fraction of the promises touted. Mount Hays, the larger of two mountains on Kaien Island, is named in his honour, as is a local high school, Charles Hays Secondary School. The train station, a listed historic place,[12] replaced the temporary building in 1922.[13]

20th and 21st centuries

Local politicians used the promise of a highway connected to the mainland as an incentive, and the city grew over the next several decades. American troops finally completed the road between Prince Rupert and Terrace during World War II to help move thousands of allied troops to the Aleutian Islands and the Pacific. Several forts were built to protect the city at Barrett Point and Fredrick Point.[14]

After World War II, the fishing industry, particularly for salmon and halibut, and forestry became the city's major industries. Prince Rupert was considered the Halibut Capital of the World from the opening of the Canadian Fish & Cold Storage plant in 1912 until the early 1980s.[15][16] A long-standing dispute over fishing rights in the Dixon Entrance to the Hecate Strait (pronounced as "hekk-et") between American and Canadian fisherman led to the formation of the 54-40 or Fight Society. The United States Coast Guard maintains a base in nearby Ketchikan, Alaska.

In 1946, the Government of Canada, through an Order in Council, granted the Department of National Defence the power to administer and maintain facilities to collect data for communications research. The Royal Canadian Navy was allotted forty positions, seven of which were in Prince Rupert. In either 1948 or 1949, Prince Rupert ceased operations, and the positions were relocated to RCAF Whitehorse, Yukon. The 1949 Queen Charlotte earthquake, with a surface wave magnitude of 8.1 and a maximum Mercalli intensity of VIII (Severe), broke windows and swayed buildings on August 22.

In Summer 1958, Prince Rupert endured a riot over racial discrimination. Ongoing discontent with heavy-handed police practices towards Aboriginals escalated to rioting during BC Centennial celebrations following the arrest of an Aboriginal couple. As many as 1,000 people (one tenth of the city's population at the time) began smashing windows and skirmishing with police. The Riot Act was read for only the second time since Confederation.[17][18][19]

Over the years, hundreds of students were said to have largely paid their way through school by working in the lucrative fishing industry. Construction of a pulp mill began in 1947 and it was operating by 1951. The construction of coal and grain shipping terminals followed. From the 1960s into the 1980s, the city constructed many improvements, including a civic centre, swimming pool, public library, golf course and performing arts centre (recently renamed "The Lester Centre of the Arts"). These developments marked the town's changes from a fishing and mill town into a small city.

In the 1990s, both the fishing and forestry industries suffered a significant downturn. In July 1997, Canadian fishermen blockaded the Alaska Marine Highway ferry M/V Malaspina, keeping it in the port as a protest in the salmon fishing rights dispute between Alaska and British Columbia. The forest industry declined when a softwood lumber dispute arose between Canada and the USA. After the pulp mill closed, many people were unemployed, and much modern machinery was left unused. After reaching a peak of about 18,000 in the early 1990s, Prince Rupert's population began to decline, as people left in search of work.

The years from 1996 to 2004 were difficult for Prince Rupert, with closure of the pulp mill, the burning down of a fish plant and a significant population decline. 2005 may be viewed as a critical turning point: the announcement of the construction of a container port in April 2005, combined with new ownership of the pulp mill, the opening in 2004 of a new cruise ship dock, the resurgence of coal and grain shipping, and the prospects of increased heavy industry and tourism may foretell a bright future for the area. The port is becoming an important trans-Pacific hub.[20]

Geography

Prince Rupert is on Kaien Island (approximately 770 km (480 mi) northwest of Vancouver), just north of the mouth of Skeena River, and linked by a short bridge to the mainland. The city is along the island's northwestern shore, fronting on Prince Rupert Harbour.

At the secondary western terminus of Trans-Canada Highway 16 (the Yellowhead Highway), Prince Rupert is approximately 16 km west of Port Edward, 144 km west of Terrace, and 715 km west of Prince George.

Climate

Prince Rupert has an oceanic climate (Köppen Cfb) and is also in a temperate rainforest. Prince Rupert is known as "The City of Rainbows",[21] as it is Canada's wettest city, with 2,620 millimetres (103 in) of annual precipitation on average, of which 2,530 millimetres (99.6 in) is rain; in addition, 240 days per year receive at least some measurable precipitation, and there are only 1230 hours of sunshine per year, so it is regarded as the municipality in Canada which receives the lowest amount of sunshine annually. Tourist brochures boast about Prince Rupert's "100 days of sunshine". However, Stewart, British Columbia receives even less sunshine, at 985 sunshine hours per year.[22]

Out of Canada's 100 largest cities, Prince Rupert has the coolest summer, with an average high of 15.67 °C (60.2 °F).[23] Winters in Prince Rupert are mild by Canadian standards, with the average afternoon temperature in December, January and February being 5.2 °C (41.4 °F) which is the tenth warmest in Canada, surpassed only by other British Columbia cities.[24]

Summers are mild and comparatively less rainy, with an August daily mean of 13.8 °C (56.8 °F). Spring and autumn are not particularly well-defined; rainfall nevertheless peaks in the autumn months. Winters are chilly and damp, but warmer than most locations at a similar latitude, due to Pacific moderation: the January daily mean is 2.4 °C (36.3 °F), although frosts and blasts of cold Arctic air from the northeast are not uncommon.

Snow amounts are moderate for Canadian standards, averaging 126 centimetres (50 in) and occurring mostly from December to March. Snowfall in Prince Rupert is rare and the snow normally melts within a few days, although individual snowstorms may bring copious amounts of snow. Wind speeds are relatively strong, with prevailing winds blowing from the southeast.

The highest temperature ever recorded in Prince Rupert was 32.2 °C (90 °F) on 6 June 1958.[25] The lowest temperature ever recorded was −24.4 °C (−12 °F) on 4 January 1965.[26]

| Climate data for Prince Rupert Airport, 1981–2010 normals, extremes 1908–present[lower-alpha 1] | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Record high humidex | 17.2 | 18.6 | 17.9 | 22.8 | 29.3 | 27.8 | 29.1 | 31.6 | 28.5 | 23.4 | 19.3 | 16.1 | 31.6 |

| Record high °C (°F) | 17.8 (64.0) |

18.9 (66.0) |

20.0 (68.0) |

25.5 (77.9) |

29.4 (84.9) |

32.2 (90.0) |

30.6 (87.1) |

30.0 (86.0) |

27.0 (80.6) |

21.7 (71.1) |

20.0 (68.0) |

18.9 (66.0) |

32.2 (90.0) |

| Average high °C (°F) | 5.6 (42.1) |

6.1 (43.0) |

7.7 (45.9) |

10.2 (50.4) |

12.6 (54.7) |

14.7 (58.5) |

16.2 (61.2) |

17.0 (62.6) |

14.9 (58.8) |

11.1 (52.0) |

7.3 (45.1) |

5.5 (41.9) |

10.8 (51.4) |

| Daily mean °C (°F) | 2.4 (36.3) |

2.7 (36.9) |

4.2 (39.6) |

6.4 (43.5) |

9.0 (48.2) |

11.6 (52.9) |

13.4 (56.1) |

13.8 (56.8) |

11.5 (52.7) |

8.0 (46.4) |

4.3 (39.7) |

2.7 (36.9) |

7.5 (45.5) |

| Average low °C (°F) | −0.8 (30.6) |

−0.7 (30.7) |

0.6 (33.1) |

2.5 (36.5) |

5.4 (41.7) |

8.4 (47.1) |

10.5 (50.9) |

10.6 (51.1) |

8.0 (46.4) |

4.9 (40.8) |

1.3 (34.3) |

−0.2 (31.6) |

4.2 (39.6) |

| Record low °C (°F) | −24.4 (−11.9) |

−18.1 (−0.6) |

−17.2 (1.0) |

−7.1 (19.2) |

−3.7 (25.3) |

1.1 (34.0) |

2.8 (37.0) |

2.8 (37.0) |

−2.2 (28.0) |

−11.3 (11.7) |

−20.6 (−5.1) |

−22.8 (−9.0) |

−24.4 (−11.9) |

| Record low wind chill | −34 | −25 | −23 | −11 | −5 | −1 | 1 | 0 | −6 | −17 | −28 | −31 | −34 |

| Average precipitation mm (inches) | 276.3 (10.88) |

185.6 (7.31) |

199.6 (7.86) |

172.4 (6.79) |

137.6 (5.42) |

108.8 (4.28) |

118.7 (4.67) |

169.1 (6.66) |

266.3 (10.48) |

373.6 (14.71) |

317.0 (12.48) |

294.2 (11.58) |

2,619.1 (103.11) |

| Average rainfall mm (inches) | 252.9 (9.96) |

167.1 (6.58) |

188.4 (7.42) |

169.6 (6.68) |

137.5 (5.41) |

108.7 (4.28) |

118.7 (4.67) |

169.1 (6.66) |

266.3 (10.48) |

373.4 (14.70) |

306.9 (12.08) |

271.7 (10.70) |

2,530.4 (99.62) |

| Average snowfall cm (inches) | 25.6 (10.1) |

19.3 (7.6) |

11.8 (4.6) |

2.8 (1.1) |

0.1 (0.0) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.3 (0.1) |

9.7 (3.8) |

22.8 (9.0) |

92.4 (36.4) |

| Average precipitation days (≥ 0.2 mm) | 22.5 | 18.5 | 21.7 | 19.6 | 18.3 | 17.3 | 17.5 | 17.5 | 19.8 | 24.2 | 23.8 | 22.8 | 243.5 |

| Average rainy days (≥ 0.2 mm) | 20.4 | 16.4 | 20.3 | 19.4 | 18.3 | 17.3 | 17.5 | 17.5 | 19.8 | 24.2 | 23.4 | 21.5 | 235.9 |

| Average snowy days (≥ 0.2 cm) | 5.0 | 4.2 | 3.6 | 1.2 | 0.08 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.04 | 0.20 | 2.9 | 4.6 | 21.7 |

| Average relative humidity (%) (at 3pm) | 78.5 | 71.5 | 68.1 | 67.7 | 71.2 | 75.0 | 77.6 | 77.7 | 76.1 | 77.5 | 77.6 | 80.2 | 74.9 |

| Mean monthly sunshine hours | 40.1 | 65.2 | 103.0 | 145.8 | 171.1 | 154.5 | 149.7 | 149.7 | 115.7 | 72.4 | 43.0 | 32.1 | 1,242.1 |

| Percent possible sunshine | 16.2 | 23.8 | 28.1 | 34.6 | 34.5 | 30.1 | 29.1 | 32.4 | 30.2 | 22.1 | 16.7 | 13.9 | 26.0 |

| Source: Environment Canada[25][26][27][28][29][30][31][32] | |||||||||||||

Demographics

| Year | Pop. | ±% |

|---|---|---|

| 1911 | 4,184 | — |

| 1921 | 6,393 | +52.8% |

| 1931 | 6,350 | −0.7% |

| 1941 | 6,714 | +5.7% |

| 1951 | 8,546 | +27.3% |

| 1956 | 10,498 | +22.8% |

| 1961 | 11,987 | +14.2% |

| 1966 | 14,389 | +20.0% |

| 1971 | 15,747 | +9.4% |

| 1976 | 14,754 | −6.3% |

| 1981 | 16,197 | +9.8% |

| 1986 | 15,755 | −2.7% |

| 1991 | 16,620 | +5.5% |

| 1996 | 16,714 | +0.6% |

| 2001 | 14,643 | −12.4% |

| 2006 | 12,815 | −12.5% |

| 2011 | 12,508 | −2.4% |

| 2016 | 12,220 | −2.3% |

| [33][34][35][36][37][38][39] | ||

| Year | Pop. | ±% |

|---|---|---|

| 1991 | 17,359 | — |

| 1996 | 17,414 | +0.3% |

| 2001 | 15,302 | −12.1% |

| 2006 | 13,392 | −12.5% |

| 2011 | 13,052 | −2.5% |

| Canada 2016 Census | Population | % of Total Population | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Non-European Ethnicities group Source:[40] | South Asian | 405 | 3.4% |

| Chinese | 220 | 1.8% | |

| Black | 65 | 0.5% | |

| Filipino | 210 | 1.7% | |

| Latin American | 25 | 0.2% | |

| Arab | 0 | 0% | |

| Southeast Asian | 430 | 3.6% | |

| West Asian | 15 | 0.1% | |

| Korean | 10 | 0.1% | |

| Japanese | 55 | 0.5% | |

| Other visible minority | 15 | 0.1% | |

| Mixed visible minority | 35 | 0.3% | |

| Total visible minority population | 1,485 | 12.4% | |

| Aboriginal group Source:[41] | First Nations | 4,245 | 35.4% |

| Métis | 350 | 2.9% | |

| Inuit | 0 | 0% | |

| Total Aboriginal population | 4,670 | 38.9% | |

| White | 5,850 | 48.7% | |

| Total population | 12,220 | 100% | |

Population by age group 2001

- Under 18 years = 4,320 (28.2%)

- 18 – 34 years = 3,370 (22.0%)

- 35 – 54 years = 5,020 (32.8%)

- 55 – 74 years = 2,075 (13.6%)

- 75 years and over = 515 (3.4%)

- Total = 15,300 (100.0%)

- Median Age = 34.8

- Source: BC Stats Population Estimates, 2004.

Among Canadian municipalities with a population of 5,000 or more, Prince Rupert has the highest percentage of First Nations population.

Government

The mayor of Prince Rupert is Lee Brain.[1] The councillors of Prince Rupert are Nick Adey, Barry Cunningham, Blair Mirau, Wade Niesh, Reid Skelton-Morven and Gurvinder Randhawa.[42]

Prince Rupert is part of the Skeena—Bulkley Valley federal riding (electoral district). Taylor Bachrach is the Member of Parliament for the riding, and is a member of the New Democratic Party.

In the Legislative Assembly of British Columbia, Prince Rupert is a large portion of the North Coast riding. Jennifer Rice is the Member of the Legislative Assembly. She is a member of the New Democratic Party of British Columbia. The NDP traditionally has strong support in the region.

Notable residents

- Thomas Dufferin "Duff" Pattullo, politician: mayor of Prince Rupert, and Premier of British Columbia (1933 to 1941); member of the Liberal Party.

- Alexander Malcolm Manson, the first lawyer in Prince Rupert, was elected in 1916 to the BC Legislature in the riding of Omineca, Speaker of the House in 1921, appointed as both Attorney-General and Minister of Labour in 1922; later appointed to the BC Supreme Court.

- Iona Campagnolo, politician: Prince Rupert City Council, Liberal Party candidate elected in the federal riding of Skeena; in 1976 she was appointed Minister of Amateur Sports. President of the Liberal Party of Canada in 1982, and served as British Columbia's Lieutenant-Governor from 2001 to 2007.

- Dan Miller, politician: elected to the Prince Rupert Electoral District, and from August 1999 through February 2000 was Premier.

- Frederick Peters, former Premier of Prince Edward Island and legal partner of Sir Charles Hibbert Tupper, served as City Solicitor from 1911 to 1919.

- Rod Brind'Amour, former captain of the NHL's Carolina Hurricanes

- Lisa Walters, LPGA golf champion

- Paul Wong, Canadian Video Artist, now based in Vancouver, British Columbia

- Sid Dickens, an artist, now based in Vancouver, British Columbia

- Gloria Macarenko, Canadian Journalist, co-anchor CBC Vancouver, born and raised in Prince Rupert

- Takao Tanabe, CM, OBC is a painter

- Bernice Liu, is an actress and singer

- John S. MacDonald, University Professor, founding principal of MacDonald, Dettwiler and Associates Ltd

- Peter Lester, Prince Rupert's longest serving mayor Peter J. Lester was elected as a council member in 1956 and went on to become mayor in 1958. He served as the mayor of Prince Rupert for 17 terms of office for 36 years continuously. Recipient of the order of BC.

Industry

Prince Rupert relies on the fishing industry, port, and tourism.

Transport

Seaport

A belief at the beginning of the 1900s that trade expansion was shifting from Atlantic to Pacific destinations,[43] and the benefit of being closer to Asia than existing west coast ports, proved wishful. Reduced transit times to eastern North America and Europe did not outweigh the fact that rail transport has always been far more expensive than by sea.[44] The opening of the Panama Canal in 1914 exacerbated the problem.[45]

During 1906–08, the federal government undertook a hydrographic survey of the Prince Rupert harbour and approaches, finding it free of rocks or obstructions, and sufficient depth for good anchorage. Furthermore, it offered an easy entrance, fine shelter, and ample space. By 1909, a 1,500-foot wharf had been constructed.[46]

The port possesses the deepest ice-free natural harbour in North America, and the 3rd deepest natural harbour in the world.[47] Situated at 54° North, the harbour is the northwesternmost port in North America linked to the continent's railway network. The port is the first inbound and last outbound port of call for some cargo ships travelling between eastern Asia and western North America since it is the closest North American port to key Asian destinations.[48][49] The CN Aquatrain barge carries rail cargo between Prince Rupert and Whittier, Alaska.[50][51][52]

Passenger ferries operating from Prince Rupert include BC Ferries' service to the Haida Gwaii and to Port Hardy on Vancouver Island, and Alaska Marine Highway ferries to Ketchikan, Juneau and Sitka and many other ports along Alaska's Inside Passage. The Prince Rupert Ferry Terminal is co-located with the Prince Rupert railway station, from which Via Rail offers a thrice-weekly Jasper – Prince Rupert train, connecting to Prince George and Jasper, and through a connection with The Canadian, to the rest of the continental passenger rail network.

The Prince Rupert Port Authority is responsible for the port's operation.

Much of the harbour is formed by the shelter provided by Digby Island, which lies windward of the city and contains the Prince Rupert Airport. The city is on Kaien Island and the harbour also includes Tuck Inlet, Morse Basin, Wainwright Basin, and Porpoise Harbour, as well as part of the waters of Chatham Sound which takes in Ridley Island.

Port facilities

.jpg.webp)

Prince Rupert is ideally located for a port, having the deepest natural harbour depths on the continent.[53][54] The city's port capacity is comparable with the Port of Vancouver's. Unlike most west coast ports, there is little traffic congestion at Prince Rupert. Finally, the extremely mountainous nature and narrow channels of the surrounding area leaves Prince Rupert as the only suitable port location in the inland passage region.

The Prince Rupert Port Authority (PRPA) is a federally appointed agency which administers and operates various port properties on the harbour. Previously run by the National Harbours Board and subsequently the Prince Rupert Port Corporation, the PRPA is now a locally run organization.

PRPA port facilities include:

- Atlin Terminal [55]

- Northlands Terminal [56]

- Lightening Dock

- Ocean Dock

- Westview Dock

- Fairview Terminal [57]

- Prince Rupert Grain [58]

- Ridley Terminals [59]

- Sulphur Corporation

All PRPA facilities are serviced by CN Rail.

The Canadian Coast Guard maintains CCG Base Seal Cove on Prince Rupert Harbour where vessels are homeported for search and rescue and maintenance of aids to navigation throughout the north coast. CCG also bases helicopters at Prince Rupert for servicing remote locations with aids to navigation, as well as operating a Marine Communications Centre, covering a large Vessel Traffic Services zone from Port Hardy at the northern tip of Vancouver Island to the International Boundary north of Prince Rupert.

Both BC Ferries and the Alaska Marine Highway operate ferries which call at Prince Rupert, with destinations in the Alaska Panhandle, the Haida Gwaii, and isolated communities along the central coast to the south.

Airport

Prince Rupert Airport (YPR/CYPR) is on Digby Island. Its position is 54°17′10″N 130°26′41″W, and its elevation is 35 m (116 ft[60]) above sea level. The airport consists of one runway, one passenger terminal, and two aircraft stands. Access to the airport is typically achieved by a bus connection that departs from downtown Prince Rupert (Highliner Hotel) and travels to Digby Island by ferry. The airport is served by Air Canada from Vancouver International Airport (YVR).

Prince Rupert is also served by the Prince Rupert/Seal Cove Water Aerodrome, a seaplane facility with regularly scheduled, as well as chartered, flights to nearby villages and remote locations.

Railway

CN Rail has a mainline that runs to Prince Rupert from Valemount, British Columbia. At Valemount, the Prince Rupert mainline joins the CN mainline from Vancouver. Freight traffic on the Prince Rupert mainline consists primarily of grain, coal, wood products, chemicals, and as of 2007, containers. As the renovations at the Port of Prince Rupert continue, traffic on CN will steadily rise in future years.

In addition, a three times weekly Jasper – Prince Rupert train operated by Via Rail connects Prince Rupert with Prince George and Jasper. Running during daylight hours to allow passengers to be able to see the scenery along the entire route; the service takes two days and requires an overnight hotel stay in Prince George. The route ends in Jasper and connects passengers with Via's The Canadian, which runs between Toronto and Vancouver.

Communications

Telephone, mobile, and Internet service are provided by CityWest (formerly CityTel). CityWest is owned by the City of Prince Rupert. CityWest provides long-distance telephone service, as does Telus.

In September 2005, the city changed CityTel from a city department into an independent corporation named CityWest. The new corporation immediately purchased the local cable company, Monarch Cablesystems, expanding CityWest's customer base to other northwest British Columbia communities.

Since January 2008, Rogers Communications has offered GSM and EDGE service in the area—the first real competition to CityWest's virtual monopoly. Rogers offers local numbers based in Port Edward (prefix 600), which is in the local calling zone for the Prince Rupert area. The introduction of Rogers service forced Citywest to form a partnership with Bell Canada to bring digital services to Citywest Mobility, using CDMA.

In December 2013, CityWest and TELUS announced it was transitioning out of the cellular business over 2014 and would partner with TELUS to bring CityWest wireless customers onto TELUS' 4G wireless network.[61]

Media

Radio

Newspapers

- Prince Rupert Daily News, daily newspaper, (1911–2010)

- The Northern View, local weekly newspaper, 2006–present, owned by Black Press

- The Northern Connector, regional weekly newspaper covering Prince Rupert, Kitimat and Terrace areas, 2006–present, owned by Black Press

Tourist attractions

Prince Rupert is a central point on the Inside Passage, a route of relatively sheltered waters running along the Pacific coast from Vancouver, British Columbia to Skagway, Alaska. Many cruise ships visit during the summer en route between Alaska to the north and Vancouver and the Lower 48 to the south.

Prince Rupert is also the starting point for many wildlife viewing trips including whales, eagles, salmon and grizzly bears. The Khutzeymateen Grizzly Bear sanctuary features one of the densest remaining populations in North America; tours can be arranged by water, air (using float planes) or land departing from Prince Rupert.

Neighbouring communities

By virtue of location, Prince Rupert is the gateway to many destinations:

- Dodge Cove (1 km, 0.6 mi, west)

- Metlakatla (5 km, 3 mi, west)

- Port Edward (15 km, 9 mi, south)

- Lax Kw'alaams (Port Simpson) (30 km, 19 mi, northwest)

- Oona River (43 km, 27 mi, southwest)

- Kitkatla (65 km, 40 mi, south)

- Kisumkalum (140 km, 87 mi, east)

- Kitselas (142 km, 88 mi, east)

- Terrace (146 km, 87 mi, east)

- Hartley Bay (157 km, 98 mi, southeast)

The Haida Gwaii are to the west of Prince Rupert, across the Hecate Strait. Alaska is 49 nautical miles (90 km, 56 mi) north of Prince Rupert.

In popular culture

The book Unmarked: Landscapes Along Highway 16, written by Sarah de Leeuw, includes an essay about Prince Rupert entitled "Highway of Monsters".

Ra McGuire of the band Trooper wrote the hit song "Santa Maria" on a boat in Prince Rupert's Harbour. Says McGuire, "The boat was called The Lucky Lady. We sailed from Prince Rupert onto an island [62] off the coast with an awful lot of alcohol and some salmon to barbecue. Many of the lines in the song are direct quotes from the skipper (the late Patty Green). He actually said 'Okay, there's only fear and good judgment holding us back.' On the way back he said 'Does somebody know how to drive this thing?' I actually wrote these down in a little notepad as we went." [63]

Amuro Ray, the protagonist of the anime series Mobile Suit Gundam, was born and raised in Prince Rupert.[64]

Notes

- "Mayor - City of Prince Rupert". www.princerupert.ca. Archived from the original on 2017-07-19. Retrieved 1 May 2018.

- Census Profile, 2016 Census - Prince Rupert, City Census subdivision, British Columbia and British Columbia Archived 2017-07-19 at the Wayback Machine

- MacDonald, George F.; Inglis, Richard I. An Overview of the North Coast Prehistory Project (1966-1980) (Report).

- MacKay 1986, pp. 86 & 87.

- Hamilton, William (1978). The Macmillan Book of Canadian Place Names. Toronto: Macmillan. p. 48. ISBN 0-7715-9754-1.

- Bowman 1980, pp. 20–21 & 27.

- Bowman 1980, pp. 20, 28, 52 & 54.

- Bowman 1980, pp. 23–24.

- Bowman 1980, p. 29.

- Talbot, The Making of a Great Canadian Railway...The Grand Trunk Pacific Railway, (1912, The Musson Book Co.), at pp. 318-19; BC Names entry "Prince Rupert (city)" Archived 2013-12-12 at Wikiwix

- Bowman 1980, pp. 33–37.

- "Canada's Historic Places, Prince Rupert". www.historicplaces.ca.

- Bohi, Charles W.; Kozma, Leslie S. (2002). Canadian National's Western Stations. Fitzhenry & Whiteside. pp. 122, 138 & 142. ISBN 1550416324.

- Bowman 1980, p. 76–78.

- Bowman 1980, p. 67.

- "About Prince Rupert". www.princerupert.ca.

- "canada.com - Page Not Found". Archived from the original on 6 July 2014. Retrieved 1 May 2018 – via Canada.com. Cite uses generic title (help)

- "Prince Rupert Fire Museum". www.princerupertlibrary.ca. Archived from the original on 26 October 2016. Retrieved 1 May 2018.

- Prince George Citizen: 4, 5, 7 & 11 Aug 1958

- Pearson, Natalie Obiko. (13 August 2018). "Busiest Pacific Port in North America Thrives Amid Trump Tirades". Bloomberg website Retrieved 3 January 2020.

- Grant Lawrence. "Soaking up the sights in Canada's soggiest city — Prince Rupert". Vancouver Courier. Retrieved March 18, 2020.

- "Canadian Climate Normals 1981–2010 Station Data". Environment Canada. Retrieved 16 July 2014.

- "Coolest summer". Environment Canada. Archived from the original on 2013-05-16. Retrieved 2013-01-06.

- "Mildest winter". Environment Canada. Archived from the original on 2013-05-16. Retrieved 2013-01-06.

- "Daily Data Report for June 1958". Canadian Climate Data. Environment Canada. Archived from the original on 10 August 2016. Retrieved 17 June 2016.

- "Prince Rupert A". Canadian Climate Normals 1981–2010. Environment Canada. Archived from the original on 10 August 2016. Retrieved 27 August 2015.

- "Daily Data Report for January 1958". Canadian Climate Data. Environment Canada. Archived from the original on 10 August 2016. Retrieved 17 June 2016.

- "Daily Data Report for March 1926". Canadian Climate Data. Environment Canada. Archived from the original on 10 August 2016. Retrieved 17 June 2016.

- "Daily Data Report for May 1912". Canadian Climate Data. Environment Canada. Archived from the original on 10 August 2016. Retrieved 17 June 2016.

- "Daily Data Report for July 1949". Canadian Climate Data. Environment Canada. Archived from the original on 10 August 2016. Retrieved 17 June 2016.

- "Daily Data Report for August 1916". Canadian Climate Data. Environment Canada. Archived from the original on 10 August 2016. Retrieved 17 June 2016.

- "Daily Data Report for November 1949". Canadian Climate Data. Environment Canada. Archived from the original on 10 August 2016. Retrieved 17 June 2016.

- Archived 2014-10-19 at the Wayback Machine, Censuses 1871–1931

- Archived 2013-12-09 at the Wayback Machine, Census 1941–1951

- Archived 2014-12-23 at the Wayback Machine, Census 1961

- Archived 2014-12-23 at the Wayback Machine, Canada Year Book 1974: Censuses 1966, 1971

- Archived 2014-12-23 at the Wayback Machine, Canada Year Book 1988: Censuses 1981, 1986

- Columbia.html, Census 1991–2006

- , A Demographic Profile of Prince Rupert

- "Community Profiles from the 2011 Census, Statistics Canada - Census Subdivision". 2.statcan.gc.ca. 2010-12-06. Archived from the original on 2016-03-03. Retrieved 2013-04-13.

- "Aboriginal Peoples - Data table". 2.statcan.ca. 2010-10-06. Archived from the original on 2015-07-05. Retrieved 2013-04-13.

- "Councillors - City of Prince Rupert". www.princerupert.ca. Archived from the original on 2017-07-19. Retrieved 1 May 2018.

- MacKay 1986, p. 142.

- Bowman 1980, p. 30.

- MacKay 1986, p. 146.

- Bowman 1980, pp. 19 & 21.

- Prince Rupert Archived 2011-06-11 at the Wayback Machine www.vancouverisland.com

- "Shortest sailing time to Asian markets gives Prince Rupert Port a major edge in exports". Export Development Canada. 28 February 2018. Retrieved 11 September 2019.

- "Prince Rupert Transit Time Advantage". CN. Canadian National Railway. Retrieved 11 September 2019.

- Cook, Adam (2017-10-10). "CN's Aquatrain Connecting Canada and the Continental US to the Alaskan market | cn.ca". www.cn.ca. Archived from the original on 2019-10-21. Retrieved 2019-10-21.

- "Megatrains - Ep 3 - Aqua Train (at 1m15s)". Earth Touch Sales & Distribution. 2015.

- "Alaska Railroad Industries AquaTrain". www.alaskarails.org. 9 March 2016.

- "Major Investment in Prince Rupert Port Expansion" - Industry Canada - April 15, 2005

- "Prince Rupert Container Terminal Opening New World of Opportunities" Archived 2011-09-27 at the Wayback Machine - Western Economic Diversification Canada - September 12, 2007

- Atlin Terminal | Prince Rupert Port Authority Archived 2010-04-25 at the Wayback Machine. Rupertport.com. Retrieved on 2013-07-26.

- Northland Cruise Terminal | Prince Rupert Port Authority Archived 2010-04-25 at the Wayback Machine. Rupertport.com. Retrieved on 2013-07-26.

- Prince Rupert Container Terminal | Prince Rupert Port Authority Archived 2010-05-06 at the Wayback Machine. Rupertport.com (2007-10-31). Retrieved on 2013-07-26.

- Prince Rupert Grain | Prince Rupert Port Authority Archived 2010-03-30 at the Wayback Machine. Rupertport.com. Retrieved on 2013-07-26.

- Ridley Terminals | Prince Rupert Port Authority Archived 2010-08-05 at the Wayback Machine. Rupertport.com. Retrieved on 2013-07-26.

- This is a measured value in feet

- "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 2015-11-19. Retrieved 2015-11-19.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- "Lucy Island Lighthouse". fogwhistle.ca. Archived from the original on 2015-03-12. Retrieved 2014-12-05.

- "Trooper Official Site - Canadian rock band -". trooper.ca. Archived from the original on 2008-03-06. Retrieved 2014-12-05.

- Dynasty Warriors Gundam 2, file 1 of Personal History, "Born in Prince Rupert, West Coast of North America"

- Climate data was recorded in Prince Rupert from August 1908 to December 1962 and at Prince Rupert Airport from May 1962 to present.

References

- "Prince George archival newspapers". www.pgpl.ca.

- Bowman, Phylis (1980). Whistling Through The West. Self-published. ISBN 0969090129.

- MacKay, Donald (1986). The Asian Dream: The Pacific Rim and Canada's National Railway. Douglas & McIntyre. ISBN 0-88894-501-9.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Prince Rupert, British Columbia. |

| Wikivoyage has a travel guide for Prince Rupert. |