Cephalopod attack

Cephalapod attacks on humans have been reported since ancient times. A significant portion of these are unverifiable tabloid stories, or at least questionable. Cephalopods are members of the class Cephalopoda, which include all squid, octopuses, cuttlefish, and nautiluses. Some members of the group are capable of causing injury or even death to humans.

Defenses

Tentacles

Tentacles are the major organs used by squid for defending and hunting. They are often confused with arms—octopuses have eight arms, while squid and cuttlefish have eight arms and two tentacles. These tentacles are generally longer than arms and typically have suckers only on their ends instead of along the entire length. The giant squid and colossal squid have some of the largest tentacles in the world, with suckers capable of producing suction forces more than 800 kilopascals (roughly 100 pounds per square inch)[1] and with pointed teeth at the tips.

Beak

The cephalopod beak resembles that of a parrot. It is a tough structure made of chitin and marks the beginning of the cephalopod's digestive system. Colossal squid use their beaks for shearing and slicing prey's flesh to allow the pieces to travel the narrow esophagus.

One of the largest beaks ever recorded was on a 495-kilogram (1,091 lb) colossal squid. The beak had a lower rostral length of 42.5 millimeters (1 11⁄16 in). Many beaks have also been discovered in the stomachs of sperm whales, as the stomach juices dissolve the soft flesh of the squid, leaving the hard beaks behind. The largest beak ever discovered this way had a lower rostral length of 49 millimeters (1 15⁄16 in), indicating that the original squid was 600 to 700 kilograms (1,300 to 1,500 lb).[2]

Venom

All octopuses have venom, but few are fatally dangerous. The greater blue-ringed octopus, however, is considered to be one of the most venomous animals known; the venom of one is enough to kill ten grown men.[3] It uses the neurotoxin tetrodotoxin, which quickly causes respiratory arrest. Estimates of the number of recorded fatalities caused by blue-ringed octopuses vary, ranging from seven to sixteen deaths; most scholars agree that there are at least eleven.[4]

Attacks on humans

Common octopus

- Alfred Brehm (1829–1884) in the 19th century was one of the most significant naturalists of the 20th century. In the section on the giant squid in his famous book, Animal World, he mentions: "Most of the data on these giant octopuses can be found in Montfort’s book, The Natural History of Mollusks. There is talk of a sea monster grabbing the mast of a ship off the coast of Angola with its arms and almost pulling the ship down into the abyss, on the occasion of which the lucky crew painted this great danger in a vow. in the chapel of St. Thomas of Maló. He further talks about another polyph in the wake of Montfort, Captain Dens; it pulled some sailors off the ship's rack with his arms near St. Ilona; the end of one arm, which was stuck in the rigging of the ship and which had been cut off, proved to be 25 feet long and had several rows of suction discs on it."[5]

- American traveler Frederick O'Brien (1869–1932) reports during his research in the Marquises Islands that a relative of one of the locals was killed by a large octopus living in the coastal countryside.[6]

- An undetermined date (sometime in the early 20th century): a diver was attacked by a large octopus in the military port of Toulon. The diver almost drowned and lost consciousness. Luckily, the diver's companions were able to pull him out of the water and only there could he take the animal off of it. The octopus weighed about 60 kilograms and had legs 8 meters long.[7]

- According to a certain Pernetti ("Voyage aux iles Malouines") off the coast of Angola, a huge 8-armed octopus climbed aboard. It was so severe that the ship capsized halfway. The rest of the story is unknown.[8]

While octopuses generally avoid humans, attacks have occasionally been verified. For example, a 240-centimeter (8-foot) Pacific octopus, said to be nearly perfectly camouflaged, "lunged" at a diver and "wrangled" over his camera. Another diver recorded the encounter on video.[9]

The supposed attack on a Staten Island ferry in New York, leading to the loss of the ferry and commemorated by a bronze sculpture (installed in 2016), never actually occurred, nor was there any such ferry disaster. The artist responsible admitted it was "a multimedia art project and social experience – not maliciously – about how gullible people are".[10]

In the 1960s, divers would willingly grapple octopuses in octopus wrestling, a then-popular sport in coastal United States.

Giant Pacific octopus

- In another part of "River Monsters", in "Terror in Paradise" Jeremy Wade reports that a fisherman has been attacked by a giant octopus on the North American coast of the Pacific Ocean.[11]

Giant or colossal squid

- The French ship Ville de Paris participated in the American War of Independence. She sailed the company of nine other ships when she was attacked by huge giant squids and dragged down into the deep.[12] This might be just a legend, as according to other sources, the ship sank in a storm in 1782.[13]

- Based on other sources, Hungarian traveller Dr. Endre Jékely tells several of the above stories. He also mentions a case in which an English ship sank in World War II, with the few survivors being able to cling to a small raft in which not everyone could fit. The first night, a giant squid attacked them and dragged a companion down into the deep. This was repeated several times with the survivors until they were finally rescued by another ship.[14]

- In the 1930s, Norwegian tanker Brunswick reported having been attacked by a giant squid in the South Pacific between Hawaii and Samoa. The animal tried unsuccessfully to grip the ship with his tentacles before being killed by the propellers.[15] The story was validated by Commander Arne Groenningsaeter of the Royal Norwegian Navy, stating that the ship had not one, but three encounters with giant squids between 1930 and 1933.[16]

- A giant squid allegedly attacked a raft with survivors from the Britannia in 1941, which had been sunk in the South Atlantic. One of the men was dragged away by the squid, and another, Lieutenant R. E. G. Cox, managed to narrowly escape the same fate, though suffering tentacle sucker wounds.[17][18] The chronicle of the survivors was first told in 1941 by the London Illustrated News, which stated that, according to the account given them by Cox, a survivor first had his legs bitten off by a shark and then was devoured by a giant manta,[19][20] but in 1956, Cox himself contacted writer Frank W. Lane to tell his story.[21] They required marine naturalist John Cloudsley-Thompson to examine Cox's scars at Birkbeck College, and the former further validated the story, assuring the marks, of 1-1/4 inches in size, belonged to a 23-feet long squid.[21][22][23] The story has been called the only substantiated report of a giant squid killing humans.[21]

- In 2003, the crew of a yacht competing to win the round-the-world Jules Verne Trophy reported being attacked by a giant squid several hours after departing from Brittany, France. The squid purportedly latched onto the ship and blocked the rudder with two tentacles. Olivier de Kersauson (captain of the yacht) then stopped the boat, causing the squid to lose interest. "We didn't have anything to scare off this beast, so I don't know what we would have done if it hadn't let go," Kersauson said.[24]

Humboldt squid

- Humboldt squid are notorious for their aggression. In Mexico, they are known as diablo rojo (Spanish for 'red devil'): local fishermen's tales claim that people who fell into the waters were devoured within minutes by packs of squid. Wildlife filmmaker Scott Cassell made the documentary "Humboldt: The Man-Eating Squid" for the Dangerous Waters series of the Discovery Channel.[25]

- There is some disagreement on the veracity of Humboldt squid aggression. Some scientists claim the only reports of aggression towards humans have occurred when reflective diving gear or flashing lights have been present, acting as provocation. Roger Uzun, a veteran scuba diver and amateur underwater videographer, swam with a swarm of Humboldt squid for approximately 20 minutes, later saying they seemed more curious than aggressive.[26] When not feeding or being hunted, Humboldt squid exhibit curious and intelligent behavior.[27]

- Jeremy Wade (1956–) deals with the Humboldt squid in his documentary River Monsters. Here, a California fisherman claims to have been attacked at a fish table one night as he tried to swim from one boat to another. In the same film, a Peruvian fishermen consider this animal to be life-threatening: if one gets between them, they will be dragged down into the deep.[28]

- In another film by naturalist Steve Backshall, fishermen report, among other things, that a fisherman was caught in the abyss by a squid. Another fisherman was bitten by the squid on his skull, breaking his skull.[29]

Gallery

Common octopus (Octopus vulgaris, max. 1–2 m)

Giant Pacific octopus (Enteroctopus dofleini, max. 9 m)

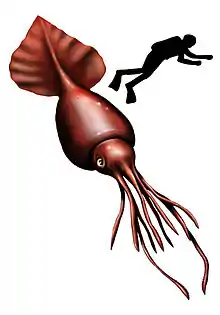

Humboldt squid (Dosidicus gigas, max. 1,5 m)

Giant squid (Architeuthis dux, max. 10–12 m, according to older reports, up to 20–21 m)

Colossal squid (Mesonychoteuthis hamiltoni, max. 12–14 m)

References

- Smith, Andrew M. (12 December 1995), "Cephalopod Sucker Design and the Physical Limits to Negative Pressure", Journal of Experimental Biology, 199 (199): 949–958, PMID 9318745

- Te Papa, The Beak of the Colossal Squid, Museum of New Zealand Te Papa Tongawera, retrieved 17 April 2011

- Williamson 1996, p. 332.

- Williamson, John A. (1996), Venomous and Poisonous Marine Animals: a Medical and Biological Handbook, UNSW Press

- "Elsö Osztály: Lábasfejűek Vagy Polipok (Cephalopoda)". mek.oszk.hu.

- Frederick O'Brien: A haldokló szigetvilág, Dante Kiadás, Budapest, 1930s

- Leidenfrost Gyula: Keserű tenger, Franklin Társulat, Budapest, 1936, 82p

- Leidenfrost, 83p

- Ross, Philip (18 February 2014). "8-Foot Octopus Wrestles Diver Off Calif. Coast, Rare Encounter Caught on Camera". International Business Times.

- "New York monument honors victims of giant octopus attack that never occurred". The Guardian. 1 October 2016.

- https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=3L8U3kllj_s

- Leidenfrost, 84p

- Famous Fighters of the Fleet, Edward Fraser, 1904, p.164

- Dr. Jékely Endre, A vizek óriásai, Gondolat Könyvkiadó, Budapest, 1977, ISBN 963-280-338-9, 30p

- Michael Bright, There are Giants in the Sea, 1989

- Robert Hendrickson, The Ocean Almanac, 1992

- Bernard Heuvelmans, In the Wake of the Sea Serpents, p.78

- Roland Hanewald, Das Tropenbuch. Jens Peters Publ., Berlin 1987, ISBN 3-923821-13-1, S. 188.

- "SS Britannia - 1 November 1941". www.ssbritannia.org.

- Wolf H. Berger, Ocean: Reflections on a Century of Exploration

- Michael Bright, Man-Eaters: Horrifying True Stories of Savage, Flesh-Eating Predators... and their Human Prey!, 2013, St. Martin's Publishing Group, 9781466859692

- Bernard Heuvelmans, Kraken & The Colossal Octopus

- Mysterious World, episode "Monsters of the Deep", 1978

- "Wednesday, 15 January, 2003, 16:50 GMT Giant squid 'attacks French boat'". BBC. 15 January 2003. Retrieved 12 January 2012.

- Cassell, Scott Squidly, Humboldt: The Man-Eating Squid, retrieved 17 April 2011

- Jumbo squid invade San Diego shores, spook divers , Associated Press, 16 July 2009

- Behold the Humboldt squid | Outside Online

- "River Monsters: Monster Sized Special". Pink Ink. 27 May 2016. Retrieved 2 August 2017.

- https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=wcAIli76rAY