Esophagus

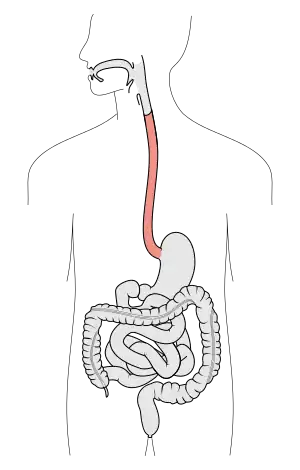

The esophagus, (American English) or oesophagus (British English; see spelling differences) (/ɪˈsɒfəɡəs/), informally known as the food pipe or gullet, is an organ in vertebrates through which food passes, aided by peristaltic contractions, from the pharynx to the stomach. The esophagus is a fibromuscular tube, about 25 cm (10 in) long in adults, which travels behind the trachea and heart, passes through the diaphragm and empties into the uppermost region of the stomach. During swallowing, the epiglottis tilts backwards to prevent food from going down the larynx and lungs. The word oesophagus is from Ancient Greek οἰσοφάγος (oisophágos), from οἴσω (oísō), future form of φέρω (phérō, “I carry”) + ἔφαγον (éphagon, “I ate”).

| Esophagus | |

|---|---|

The digestive tract, with the esophagus marked in red | |

| Details | |

| Precursor | Foregut |

| System | Part of the digestive system |

| Artery | Oesophageal arteries |

| Vein | Oesophageal veins |

| Nerve | Sympathetic trunk, vagus |

| Identifiers | |

| Latin | Oesophagus |

| MeSH | D004947 |

| TA98 | A05.4.01.001 |

| TA2 | 2887 |

| FMA | 7131 |

| Anatomical terminology | |

|

| Major parts of the |

| Gastrointestinal tract |

|---|

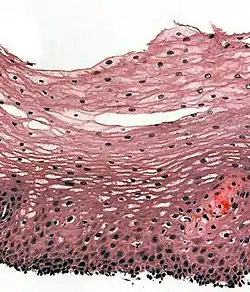

The wall of the esophagus from the lumen outwards consists of mucosa, submucosa (connective tissue), layers of muscle fibers between layers of fibrous tissue, and an outer layer of connective tissue. The mucosa is a stratified squamous epithelium of around three layers of squamous cells, which contrasts to the single layer of columnar cells of the stomach. The transition between these two types of epithelium is visible as a zig-zag line. Most of the muscle is smooth muscle although striated muscle predominates in its upper third. It has two muscular rings or sphincters in its wall, one at the top and one at the bottom. The lower sphincter helps to prevent reflux of acidic stomach content. The esophagus has a rich blood supply and venous drainage. Its smooth muscle is innervated by involuntary nerves (sympathetic nerves via the sympathetic trunk and parasympathetic nerves via the vagus nerve) and in addition voluntary nerves (lower motor neurons) which are carried in the vagus nerve to innervate its striated muscle.

The esophagus passes through the thoracic cavity into the diaphragm into the stomach.

The esophagus may be affected by gastric reflux, cancer, prominent dilated blood vessels called varices that can bleed heavily, tears, constrictions, and disorders of motility. Diseases may cause difficulty swallowing (dysphagia), painful swallowing (odynophagia), chest pain, or cause no symptoms at all. Clinical investigations include X-rays when swallowing barium sulfate, endoscopy, and CT scans. Surgically, the esophagus is difficult to access.[1]

Structure

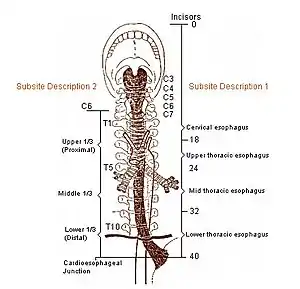

The esophagus is one of the upper parts of the digestive system. There are taste buds on its upper part.[2] It begins at the back of the mouth, passing downwards through the rear part of the mediastinum, through the diaphragm, and into the stomach. In humans, the esophagus generally starts around the level of the sixth cervical vertebra behind the cricoid cartilage of the trachea, enters the diaphragm at about the level of the tenth thoracic vertebra, and ends at the cardia of the stomach, at the level of the eleventh thoracic vertebra.[3] The esophagus is usually about 25 cm (10 in) in length.[4]

Many blood vessels serve the esophagus, with blood supply varying along its course. The upper parts of the esophagus and the upper esophageal sphincter receive blood from the inferior thyroid artery, the parts of the esophagus in the thorax from the bronchial arteries and branches directly from the thoracic aorta, and the lower parts of the esophagus and the lower esophageal sphincter receive blood from the left gastric artery and the left inferior phrenic artery.[5][6] The venous drainage also differs along the course of the esophagus. The upper and middle parts of the esophagus drain into the azygos and hemiazygos veins, and blood from the lower part drains into the left gastric vein. All these veins drain into the superior vena cava, with the exception of the left gastric vein, which is a branch of the portal vein.[5] Lymphatically, the upper third of the esophagus drains into the deep cervical lymph nodes, the middle into the superior and posterior mediastinal lymph nodes, and the lower esophagus into the gastric and celiac lymph nodes. This is similar to the lymphatic drainage of the abdominal structures that arise from the foregut, which all drain into the celiac nodes.[5]

- Position

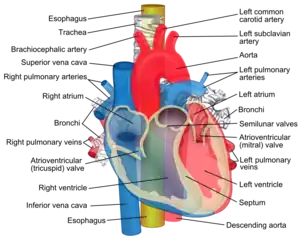

The upper esophagus lies at the back of the mediastinum behind the trachea, adjoining along the tracheoesophageal stripe, and in front of the erector spinae muscles and the vertebral column. The lower esophagus lies behind the heart and curves in front of the thoracic aorta. From the bifurcation of the trachea downwards, the esophagus passes behind the right pulmonary artery, left main bronchus, and left atrium. At this point it passes through the diaphragm.[3]

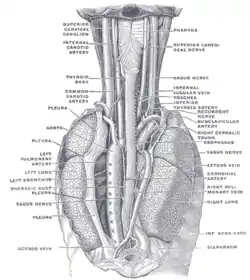

The thoracic duct, which drains the majority of the body's lymph, passes behind the esophagus, curving from lying behind the esophagus on the right in the lower part of the esophagus, to lying behind the esophagus on the left in the upper esophagus. The esophagus also lies in front of parts of the hemiazygos veins and the intercostal veins on the right side. The vagus nerve divides and covers the esophagus in a plexus.[3]

- Constrictions

The esophagus has four points of constriction. When a corrosive substance, or a solid object is swallowed, it is most likely to lodge and damage one of these four points. These constrictions arise from particular structures that compress the esophagus. These constrictions are:[7]

- At the start of the esophagus, where the laryngopharynx joins the esophagus, behind the cricoid cartilage

- Where it is crossed on the front by the aortic arch in the superior mediastinum

- Where the esophagus is compressed by the left main bronchus in the posterior mediastinum

- The esophageal hiatus where it passes through the diaphragm in the posterior mediastinum

Sphincters

The esophagus is surrounded at the top and bottom by two muscular rings, known respectively as the upper esophageal sphincter and the lower esophageal sphincter.[3] These sphincters act to close the esophagus when food is not being swallowed. The upper esophageal sphincter is an anatomical sphincter, which is formed by lower portion of inferior pharyngeal constrictor, also known as cricopharyngeal sphincter due to its relation with cricoid cartilage of the larynx anteriorly. However, the lower esophageal sphincter is not an anatomical but rather a functional sphincter, meaning that it acts as a sphincter but does not have a distinct thickening like other sphincters.

The upper esophageal sphincter surrounds the upper part of the esophagus. It consists of skeletal muscle but is not under voluntary control. Opening of the upper esophageal sphincter is triggered by the swallowing reflex. The primary muscle of the upper esophageal sphincter is the cricopharyngeal part of the inferior pharyngeal constrictor.[8]

The lower esophageal sphincter, or gastroesophageal sphincter, surrounds the lower part of the esophagus at the junction between the esophagus and the stomach.[9] It is also called the cardiac sphincter or cardioesophageal sphincter, named from the adjacent part of the stomach, the cardia. Dysfunction of the gastroesophageal sphincter causes gastroesophageal reflux, which causes heartburn and if it happens often enough, can lead to gastroesophageal reflux disease, with damage of the esophageal mucosa.[10]

Nerve supply

The esophagus is innervated by the vagus nerve and the cervical and thoracic sympathetic trunk.[5] The vagus nerve has a parasympathetic function, supplying the muscles of the esophagus and stimulating glandular contraction. Two sets of nerve fibers travel in the vagus nerve to supply the muscles. The upper striated muscle, and upper esophageal sphincter, are supplied by neurons with bodies in the nucleus ambiguus, whereas fibers that supply the smooth muscle and lower esophageal sphincter have bodies situated in the dorsal motor nucleus.[5] The vagus nerve plays the primary role in initiating peristalsis.[11] The sympathetic trunk has a sympathetic function. It may enhance the function of the vagus nerve, increasing peristalsis and glandular activity, and causing sphincter contraction. In addition, sympathetic activation may relax the muscle wall and cause blood vessel constriction.[5] Sensation along the esophagus is supplied by both nerves, with gross sensation being passed in the vagus nerve and pain passed up the sympathetic trunk.[3]

Gastro-esophageal junction

The gastro-esophageal junction (also known as the esophagogastric junction) is the junction between the esophagus and the stomach, at the lower end of the esophagus.[12] The pink color of the esophageal mucosa contrasts to the deeper red of the gastric mucosa,[5][13] and the mucosal transition can be seen as an irregular zig-zag line, which is often called the z-line.[14] Histological examination reveals abrupt transition between the stratified squamous epithelium of the esophagus and the simple columnar epithelium of the stomach.[15] Normally, the cardia of the stomach is immediately distal to the z-line[16] and the z-line coincides with the upper limit of the gastric folds of the cardia; however, when the anatomy of the mucosa is distorted in Barrets esophagus the true gastro-eshophageal junction can be identified by the upper limit of the gastric folds rather than the mucosal transition.[17] The functional location of the lower oesophageal sphincter is generally situated about 3 cm (1.2 in) below the z-line.[5]

Microanatomy

The human esophagus has a mucous membrane consisting of a tough stratified squamous epithelium without keratin, a smooth lamina propria, and a muscularis mucosae.[5] The epithelium of the esophagus has a relatively rapid turnover, and serves a protective function against the abrasive effects of food. In many animals the epithelium contains a layer of keratin, representing a coarser diet.[18] There are two types of glands, with mucus-secreting esophageal glands being found in the submucosa, and esophageal cardiac glands, similar to cardiac glands of the stomach, located in the lamina propria and most frequent in the terminal part of the organ.[18][19] The mucus from the glands gives a good protection to the lining.[20] The submucosa also contains the submucosal plexus, a network of nerve cells that is part of the enteric nervous system.[18]

The muscular layer of the esophagus has two types of muscle. The upper third of the esophagus contains striated muscle, the lower third contains smooth muscle, and the middle third contains a mixture of both.[5] Muscle is arranged in two layers: one in which the muscle fibers run longitudinal to the esophagus, and the other in which the fibers encircle the esophagus. These are separated by the myenteric plexus, a tangled network of nerve fibers involved in the secretion of mucus and in peristalsis of the smooth muscle of the esophagus. The outermost layer of the esophagus is the adventitia in most of its length, with the abdominal part being covered in serosa. This makes it distinct from many other structures in the gastrointestinal tract that only have a serosa.[5]

Development

In early embryogenesis, the esophagus develops from the endodermal primitive gut tube. The ventral part of the embryo abuts the yolk sac. During the second week of embryological development, as the embryo grows, it begins to surround parts of the sac. The enveloped portions form the basis for the adult gastrointestinal tract.[21] The sac is surrounded by a network of vitelline arteries. Over time, these arteries consolidate into the three main arteries that supply the developing gastrointestinal tract: the celiac artery, superior mesenteric artery, and inferior mesenteric artery. The areas supplied by these arteries are used to define the midgut, hindgut and foregut.[21]

The surrounded sac becomes the primitive gut. Sections of this gut begin to differentiate into the organs of the gastrointestinal tract, such as the esophagus, stomach, and intestines.[21] The esophagus develops as part of the foregut tube.[21] The innervation of the esophagus develops from the pharyngeal arches.[3]

Function

Swallowing

Food is ingested through the mouth and when swallowed passes first into the pharynx and then into the esophagus. The esophagus is thus one of the first components of the digestive system and the gastrointestinal tract. After food passes through the esophagus, it enters the stomach.[9] When food is being swallowed, the epiglottis moves backward to cover the larynx, preventing food from entering the trachea. At the same time, the upper esophageal sphincter relaxes, allowing a bolus of food to enter. Peristaltic contractions of the esophageal muscle push the food down the esophagus. These rhythmic contractions occur both as a reflex response to food that is in the mouth, and also as a response to the sensation of food within the esophagus itself. Along with peristalsis, the lower esophageal sphincter relaxes.[9]

Reducing gastric reflux

The stomach produces gastric acid, a strongly acidic mixture consisting of hydrochloric acid (HCl) and potassium and sodium salts to enable food digestion. Constriction of the upper and lower esophageal sphincters helps to prevent reflux (backflow) of gastric contents and acid into the esophagus, protecting the esophageal mucosa. The acute angle of His and the lower crura of the diaphragm also help this sphincteric action.[9][22]

Gene and protein expression

About 20,000 protein-coding genes are expressed in human cells and nearly 70% of these genes are expressed in the normal esophagus.[23][24] Some 250 of these genes are more specifically expressed in the esophagus with less than 50 genes being highly specific. The corresponding esophagus-specific proteins are mainly involved in squamous differentiation such as keratins KRT13, KRT4 and KRT6C. Other specific proteins that help lubricate the inner surface of esophagus are mucins such as MUC21 and MUC22. Many genes with elevated expression are also shared with skin and other organs that are composed of squamous epithelia.[25]

Clinical significance

The main conditions affecting the esophagus are described here. For a more complete list, see esophageal disease.

Inflammation

Inflammation of the esophagus is known as esophagitis. Reflux of gastric acids from the stomach, infection, substances ingested (for example, corrosives), some medications (such as bisphosphonates), and food allergies can all lead to esophagitis. Esophageal candidiasis is an infection of the yeast Candida albicans that may occur when a person is immunocompromised. As of 2014 the cause of some forms of esophagitis, such as eosinophilic esophagitis, is not known. Esophagitis can cause painful swallowing and is usually treated by managing the cause of the esophagitis - such as managing reflux or treating infection.[4]

Barrett's esophagus

Prolonged esophagitis, particularly from gastric reflux, is one factor thought to play a role in the development of Barrett's esophagus. In this condition, there is metaplasia of the lining of the lower esophagus, which changes from stratified squamous epithelia to simple columnar epithelia. Barrett's esophagus is thought to be one of the main contributors to the development of esophageal cancer.[4]

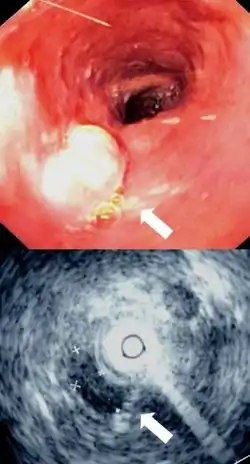

Cancer

There are two main types of cancer of the esophagus. Squamous cell carcinoma is a carcinoma that can occur in the squamous cells lining the esophagus. This type is much more common in China and Iran. The other main type is an adenocarcinoma that occurs in the glands or columnar tissue of the esophagus. This is most common in developed countries in those with Barrett's esophagus, and occurs in the cuboidal cells.[4]

In its early stages, esophageal cancer may not have any symptoms at all. When severe, esophageal cancer may eventually cause obstruction of the esophagus, making swallowing of any solid foods very difficult and causing weight loss. The progress of the cancer is staged using a system that measures how far into the esophageal wall the cancer has invaded, how many lymph nodes are affected, and whether there are any metastases in different parts of the body. Esophageal cancer is often managed with radiotherapy, chemotherapy, and may also be managed by partial surgical removal of the esophagus. Inserting a stent into the esophagus, or inserting a nasogastric tube, may also be used to ensure that a person is able to digest enough food and water. As of 2014, the prognosis for esophageal cancer is still poor, so palliative therapy may also be a focus of treatment.[4]

Varices

Esophageal varices are swollen twisted branches of the azygous vein in the lower third of the esophagus. These blood vessels anastomose (join up) with those of the portal vein when portal hypertension develops.[26] These blood vessels are engorged more than normal, and in the worst cases may partially obstruct the esophagus. These blood vessels develop as part of a collateral circulation that occurs to drain blood from the abdomen as a result of portal hypertension, usually as a result of liver diseases such as cirrhosis.[4]:941–42 This collateral circulation occurs because the lower part of the esophagus drains into the left gastric vein, which is a branch of the portal vein. Because of the extensive venous plexus that exists between this vein and other veins, if portal hypertension occurs, the direction of blood drainage in this vein may reverse, with blood draining from the portal venous system, through the plexus. Veins in the plexus may engorge and lead to varices.[5][6]

Esophageal varices often do not have symptoms until they rupture. A ruptured varix is considered a medical emergency, because varices can bleed a lot. A bleeding varix may cause a person to vomit blood, or suffer shock. To deal with a ruptured varix, a band may be placed around the bleeding blood vessel, or a small amount of a clotting agent may be injected near the bleed. A surgeon may also try to use a small inflatable balloon to apply pressure to stop the wound. IV fluids and blood products may be given in order to prevent hypovolemia from excess blood loss.[4]

Motility disorders

Several disorders affect the motility of food as it travels down the esophagus. This can cause difficult swallowing, called dysphagia, or painful swallowing, called odynophagia. Achalasia refers to a failure of the lower esophageal sphincter to relax properly, and generally develops later in life. This leads to progressive enlargement of the esophagus, and possibly eventual megaesophagus. A nutcracker esophagus refers to swallowing that can be extremely painful. Diffuse esophageal spasm is a spasm of the esophagus that can be one cause of chest pain. Such referred pain to the wall of the upper chest is quite common in esophageal conditions.[27] Sclerosis of the esophagus, such as with systemic sclerosis or in CREST syndrome may cause hardening of the walls of the esophagus and interfere with peristalsis.[4]

Malformations

Esophageal strictures are usually benign and typically develop after a person has had reflux for many years. Other strictures may include esophageal webs (which can also be congenital) and damage to the esophagus by radiotherapy, corrosive ingestion, or eosinophilic esophagitis. A Schatzki ring is fibrosis at the gastro-esophageal junction. Strictures may also develop in chronic anemia, and Plummer-Vinson syndrome.[4]

Two of the most common congenital malformations affecting the esophagus are an esophageal atresia where the esophagus ends in a blind sac instead of connecting to the stomach; and an esophageal fistula – an abnormal connection between the esophagus and the trachea.[28] Both of these conditions usually occur together.[28] These are found in about 1 in 3500 births.[29] Half of these cases may be part of a syndrome where other abnormalities are also present, particularly of the heart or limbs. The other cases occur singly.[30]

Imaging

An X-ray of swallowed barium may be used to reveal the size and shape of the esophagus, and the presence of any masses. The esophagus may also be imaged using a flexible camera inserted into the esophagus, in a procedure called an endoscopy. If an endoscopy is used on the stomach, the camera will also have to pass through the esophagus. During an endoscopy, a biopsy may be taken. If cancer of the esophagus is being investigated, other methods, including a CT scan, may also be used.[4]

History

The word esophagus (British English: oesophagus), comes from the Greek: οἰσοφάγος (oisophagos) meaning gullet. It derives from two roots (eosin) to carry and (phagos) to eat.[31] The use of the word oesophagus, has been documented in anatomical literature since at least the time of Hippocrates, who noted that "the oesophagus ... receives the greatest amount of what we consume." [32] Its existence in other animals and its relationship with the stomach was documented by the Roman naturalist Pliny the Elder (AD23–AD79),[33] and the peristaltic contractions of the esophagus have been documented since at least the time of Galen.[34]

The first attempt at surgery on the esophagus focused in the neck, and was conducted in dogs by Theodore Billroth in 1871. In 1877 Czerny carried out surgery in people. By 1908, an operation had been performed by Voeckler to remove the esophagus, and in 1933 the first surgical removal of parts of the lower esophagus, (to control esophageal cancer), had been conducted.[35]

The Nissen fundoplication, in which the stomach is wrapped around the lower esophageal sphincter to stimulate its function and control reflux, was first conducted by Rudolph Nissen in 1955.[35]

Other animals

Vertebrates

In tetrapods, the pharynx is much shorter, and the esophagus correspondingly longer, than in fish. In the majority of vertebrates, the esophagus is simply a connecting tube, but in some birds, which regurgitate components to feed their young, it is extended towards the lower end to form a crop for storing food before it enters the true stomach.[36][37] In ruminants, animals with four stomachs, a groove called the sulcus reticuli is often found in the esophagus, allowing milk to drain directly into the hind stomach, the abomasum.[38] In the horse the esophagus is about 1.2 to 1.5 m (4 to 5 ft) in length, and carries food to the stomach. A muscular ring, called the cardiac sphincter, connects the stomach to the esophagus. This sphincter is very well developed in horses. This and the oblique angle at which the esophagus connects to the stomach explains why horses cannot vomit.[39] The esophagus is also the area of the digestive tract where horses may suffer from the condition known as choke.

The esophagus of snakes is remarkable for the distension it undergoes when swallowing prey.[40]

In most fish, the esophagus is extremely short, primarily due to the length of the pharynx (which is associated with the gills). However, some fish, including lampreys, chimaeras, and lungfish, have no true stomach, so that the esophagus effectively runs from the pharynx directly to the intestine, and is therefore somewhat longer.[36]

In many vertebrates, the esophagus is lined by stratified squamous epithelium without glands. In fish, the esophagus is often lined with columnar epithelium,[37] and in amphibians, sharks and rays, the esophageal epithelium is ciliated, helping to wash food along, in addition to the action of muscular peristalsis.[36] In addition, in the bat Plecotus auritus, fish and some amphibians, glands secreting pepsinogen or hydrochloric acid have been found.[37]

The muscle of the esophagus in many mammals is striated initially, but then becomes smooth muscle in the caudal third or so. In canines and ruminants, however, it is entirely striated to allow regurgitation to feed young (canines) or regurgitation to chew cud (ruminants). It is entirely smooth muscle in amphibians, reptiles and birds.[37]

Contrary to popular belief,[41] an adult human body would not be able to pass through the esophagus of a whale, which generally measures less than 10 centimeters (4 in) in diameter, although in larger baleen whales it may be up to 25 centimeters (10 in) when fully distended.[42]

Invertebrates

A structure with the same name is often found in invertebrates, including molluscs and arthropods, connecting the oral cavity with the stomach.[43] In terms of the digestive system of snails and slugs, the mouth opens into an esophagus, which connects to the stomach. Because of torsion, which is the rotation of the main body of the animal during larval development, the esophagus usually passes around the stomach, and opens into its back, furthest from the mouth. In species that have undergone de-torsion, however, the esophagus may open into the anterior of the stomach, which is the reverse of the usual gastropod arrangement.[44] There is an extensive rostrum at the front of the esophagus in all carnivorous snails and slugs.[45] In the freshwater snail species Tarebia granifera, the brood pouch is above the esophagus.[46]

In the cephalopods, the brain often surrounds the esophagus.[47]

See also

References

- Jacobo, Julia (24 November 2016). "Thanksgiving Tales From the Emergency Room". ABC News.

- Purves, Dale (2011). Neuroscience (5th ed.). Sunderland, MA: Sinauer. p. 341. ISBN 978-0-87893-695-3.

- Drake, Richard L.; Vogl, Wayne; Tibbitts, Adam W.M. Mitchell (2005). Gray's anatomy for students. illustrations by Richard M. Tibbitts and Paul Richardson. Philadelphia: Elsevier/Churchill Livingstone. pp. 192–94. ISBN 978-0-8089-2306-0.

- Colledge, Nicki R.; Walker, Brian R.; Ralston, Stuart H., eds. (2010). Davidson's Principles and Practice of Medicine. illust. Robert Britton (21st ed.). Edinburgh: Churchill Livingstone/Elsevier. pp. 838–70. ISBN 978-0-7020-3084-0.

- Kuo, Braden; Urma, Daniela (2006). "Esophagus – anatomy and development". GI Motility Online. doi:10.1038/gimo6 (inactive 2021-01-14).CS1 maint: DOI inactive as of January 2021 (link)

- Patti, MG; Gantert, W; Way, LW (Oct 1997). "Surgery of the esophagus. Anatomy and physiology". The Surgical Clinics of North America. 77 (5): 959–70. doi:10.1016/s0039-6109(05)70600-9. PMID 9347826.

- Drake, Richard L.; Vogl, Wayne; Mitchell, Adam W.M. (2009). Gray's anatomy for students. illustrations by Richard M. Tibbitts and Paul Richardson. Philadelphia: Elsevier/Churchill Livingstone. p. 215. ISBN 978-0-443-06952-9.

- Mu, L; Wang, J; Su, H; Sanders, I (March 2007). "Adult human upper esophageal sphincter contains specialized muscle fibers expressing unusual myosin heavy chain isoforms". J. Histochem. Cytochem. 55 (3): 199–207. doi:10.1369/jhc.6A7084.2006. PMID 17074861.

- Hall, Arthur C. Guyton, John E. (2005). Textbook of medical physiology (11th ed.). Philadelphia: W.B. Saunders. pp. 782–784. ISBN 978-0-7216-0240-0.

- Kahrilas PJ (2008). "Gastroesophageal Reflux Disease". The New England Journal of Medicine. 359 (16): 1700–07. doi:10.1056/NEJMcp0804684. PMC 3058591. PMID 18923172.

- Patterson, William G. (2006). "Esophageal peristalsis". GI Motility Online. doi:10.1038/gimo13 (inactive 2021-01-14). Retrieved 24 May 2014.CS1 maint: DOI inactive as of January 2021 (link)

- John H. Dirckx, ed. (1997). Stedman's Concise Medical and Allied Health Dictionary (3rd ed.). Williams and Wilkins. p. 463. ISBN 978-0-683-23125-0.

- Anthony DiMarino, Jr.; Stanley B. Benjamin, eds. (2002). Gastrointestinal disease : an endoscopic approach. section editors Firas H. Al-Kawas (2nd ed.). Thorofare, NJ: Slack. p. 166. ISBN 978-1-55642-511-0.

- Richard M. Gore; Marc S. Levine, eds. (2010). High-yield imaging (1st ed.). Philadelphia: Saunders/Elsevier. p. 151. ISBN 978-1-4557-1144-4.

- Moore, Keith L; Agur, Anne M.R (2002). Essential Clinical Anatomy (2nd ed.). Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. p. 145. ISBN 978-0-7817-2830-0.

- Barrett, Kim E. (2014). Gastrointestinal physiology (2nd ed.). New York: Mc Graw Hill. pp. Chapter 7: "Esophageal Motility". ISBN 978-0-07-177401-7.

- Long, Richard G; Scott, Brian B, eds. (2005). Specialist Training in Gastroenterology and Liver Disease. Elsevier Mosby. pp. 25–26. ISBN 978-0-7234-3252-4.

- Ross M, Pawlina W (2011). Histology: A Text and Atlas (6th ed.). Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. pp. 571–73. ISBN 978-0-7817-7200-6.

- Takubo, Kaiyo (2007). Pathology of the esophagus an (2nd ed.). Tokyo: Springer Verlag. p. 28. ISBN 978-4-431-68616-3.

- Young, Barbara, ed. (2006). Wheater's functional histology: a text and colour atlas (5th ed.). Churchill Livingstone/Elsevier. p. 86. ISBN 978-0-443-06850-8.

- Gary C. Schoenwolf (2009). "Development of the Gastrointestinal Tract". Larsen's human embryology (4th ed.). Philadelphia: Churchill Livingstone/Elsevier. ISBN 978-0-443-06811-9.

- "Neuromuscular Anatomy of Esophagus and Lower Esophageal Sphincter - Motor Function of the Pharynx, Esophagus, and its Sphincters - NCBI Bookshelf". Ncbi.nlm.nih.gov. 2013-03-25. Retrieved 2013-04-24.

- "The human proteome in esophagus - The Human Protein Atlas". www.proteinatlas.org. Retrieved 2017-09-22.

- Uhlén, Mathias; Fagerberg, Linn; Hallström, Björn M.; Lindskog, Cecilia; Oksvold, Per; Mardinoglu, Adil; Sivertsson, Åsa; Kampf, Caroline; Sjöstedt, Evelina (2015-01-23). "Tissue-based map of the human proteome". Science. 347 (6220): 1260419. doi:10.1126/science.1260419. ISSN 0036-8075. PMID 25613900. S2CID 802377.

- Edqvist, Per-Henrik D.; Fagerberg, Linn; Hallström, Björn M.; Danielsson, Angelika; Edlund, Karolina; Uhlén, Mathias; Pontén, Fredrik (2014-11-19). "Expression of Human Skin-Specific Genes Defined by Transcriptomics and Antibody-Based Profiling". Journal of Histochemistry & Cytochemistry. 63 (2): 129–141. doi:10.1369/0022155414562646. PMC 4305515. PMID 25411189.

- Albert, Daniel (2012). Dorland's illustrated medical dictionary (32nd ed.). Philadelphia, PA: Saunders/Elsevier. p. 2025. ISBN 978-1-4160-6257-8.

- Purves, Dale (2011). Neuroscience (5. ed.). Sunderland, Mass.: Sinauer. p. 214. ISBN 978-0-87893-695-3.

- Larsen, William J. (2001). Human embryology (3. ed.). Philadelphia, Pa.: Churchill Livingstone. pp. 148–149. ISBN 978-0-443-06583-5.

- Shaw-Smith, C (18 November 2005). "esophageal atresia, tracheo-esophageal fistula, and the VACTERL association: review of genetics and epidemiology". Journal of Medical Genetics. 43 (7): 545–54. doi:10.1136/jmg.2005.038158. PMC 2564549. PMID 16299066.

- Geneviève, D; de Pontual, L; Amiel, J; Sarnacki, S; Lyonnet, S (May 2007). "An overview of isolated and syndromic oesophageal atresia". Clinical Genetics. 71 (5): 392–9. doi:10.1111/j.1399-0004.2007.00798.x. PMID 17489843. S2CID 43782279.

- Harper, Douglas. "Esophagus". Etymology Online. Retrieved 19 March 2014.

- Potter, translated by Paul, Hippocrates; edited (2010). Coan prenotions (1. publ. ed.). Cambridge, Massachusetts: Harvard University Press. p. 59. ISBN 978-0-674-99640-3.

- Bostock, John; Riley, Henry T.; Pliny the Elder (1855). The natural history of Pliny. London: H. G. Bohn. p. 64.

- Brock, Galen; with an English translation by Arthur John (1916). On the natural faculties (Repr. ed.). London: W. Heinemann. p. "Book 3" S8. ISBN 978-0-674-99078-4.

- Norton, Jeffrey A., ed. (2008). Surgery : basic science and clinical evidence (2nd ed.). New York, NY: Springer. pp. 744–746. ISBN 978-0-387-30800-5.

- Romer, Alfred Sherwood; Parsons, Thomas S. (1977). The Vertebrate Body. Philadelphia, PA: Holt-Saunders International. pp. 344–345. ISBN 978-0-03-910284-5.

- Hume, C. Edward Stevens, Ian D. (2005). Comparative physiology of the vertebrate digestive system (1st pbk. ed.). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. p. 15. ISBN 978-0-521-61714-7.

- Mackie, R. I. (1 April 2002). "Mutualistic Fermentative Digestion in the Gastrointestinal Tract: Diversity and Evolution". Integrative and Comparative Biology. 42 (2): 319–326. doi:10.1093/icb/42.2.319. PMID 21708724.

- Giffen, James M.; Gore, Tom (1998) [1989]. Horse Owner's Veterinary Handbook (2nd ed.). New York: Howell Book House. ISBN 978-0-87605-606-6.

- Cundall, D.; Tuttman, C.; Close, M. (Mar 2014). "A model of the anterior esophagus in snakes, with functional and developmental implications". Anat Rec. 297 (3): 586–98. doi:10.1002/ar.22860. PMID 24482367. S2CID 10921118.

- Eveleth, Rose (20 February 2013). "Could a Whale Accidentally Swallow You? It Is Possible". Smithsonian. Retrieved 12 April 2014.

- Tinker, Spencer Wilkie (1988). Whales of the world. Leiden: E.J. Brill. p. 60. ISBN 978-0-935848-47-2.

- Hartenstein, Volker (September 1997). "Development of the insect stomatogastric nervous system". Trends in Neurosciences. 20 (9): 421–427. doi:10.1016/S0166-2236(97)01066-7. PMID 9292972. S2CID 22477083.

- Barnes, Robert D. (1982). Invertebrate Zoology. Philadelphia, PA: Holt-Saunders International. ISBN 978-0-03-056747-6.

- Gerlach, J.; Van Bruggen, A.C. (1998). "A first record of a terrestrial mollusc without a radula". Journal of Molluscan Studies. 64 (2): 249–250. doi:10.1093/mollus/64.2.249.

- Appleton C. C., Forbes A. T.& Demetriades N. T. (2009). "The occurrence, bionomics and potential impacts of the invasive freshwater snail Tarebia granifera (Lamarck, 1822) (Gastropoda: Thiaridae) in South Africa" Archived 2014-04-16 at the Wayback Machine. Zoologische Mededelingen 83.

- Kutsch, with a coda written by T.H. Bullock; edited by O. Breidbach, W. (1994). The nervous systems of invertebrates : an evolutionary and comparative approach. Basel: Birkhäuser. p. 117. ISBN 978-3-7643-5076-5.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Esophagus. |

| Look up esophagus in Wiktionary, the free dictionary. |