Royal Norwegian Navy

The Royal Norwegian Navy (Norwegian: Sjøforsvaret, "(the) sea defence") is the branch of the Norwegian Armed Forces responsible for naval operations of Norway. As of 2008, the Royal Norwegian Navy consists of approximately 3,700 personnel (9,450 in mobilized state, 32,000 when fully mobilized) and 70 vessels, including 4 heavy frigates, 6 submarines, 14 patrol boats, 4 minesweepers, 4 minehunters, 1 mine detection vessel, 4 support vessels and 2 training vessels. It also includes the Coast Guard.

| Royal Norwegian Navy | |

|---|---|

| Sjøforsvaret | |

Coat of arms | |

| Active | 955, 1509 (not official) April 12, 1814 - present |

| Country | |

| Allegiance | Kingdom of Norway |

| Branch | Navy |

| Type | Navy |

| Role | Naval warfare |

| Size | 3,900 personnel (as of 2013; Does not include Naval Home Guard)[1] |

| Part of | Military of Norway |

| Headquarters | Haakonsvern |

| Engagements | Civil War - King Sverre (1197) Scottish–Norwegian War (1262-1266)[2] Swedish War of Liberation (1510–23) Count's Feud (1534–36) Nordic Seven Years' War (1563–70) Kalmar War (1611–13) Torstenson War (1643–45) Second Nordic War (1657–60) Scanian War (1675–79) Great Nordic War (1700 & 1709–20) Battle of Copenhagen (1801) Battle of Copenhagen (1807) Gunboat War (1807–14) First Schleswig War (1848–51) World War II (1940–45) Cold War (1945–90) War on terror (2001– ) |

| Commanders | |

| Commander in Chief | King Harald V |

| Chief of the Navy | Rear Admiral Lars Saunes[3] |

| Notable commanders | Peter Tordenskjold Cort Adeler Niels Juel Lauritz Galtung Kristoffer Throndsen Henrik Bjelke |

| Insignia | |

| Pennant and Naval Jack |  |

| Naval Ensign |  |

This navy has a history dating back to 955. From 1509 to 1814, it formed part of the navy of Denmark-Norway, also referred to as the "Common Fleet". Since 1814, the Royal Norwegian Navy has again existed as a separate navy.

In Norwegian, all its naval vessels since 1946 bear ship prefix "KNM", Kongelig Norske Marine (which accurately translates to Royal Norwegian Navy/Naval vessel). In English, they are permitted still to be ascribed prefix "HNoMS", meaning "His/Her Norwegian Majesty's Ship" ("HNMS" could be also used for the Royal Netherlands Navy, for which "HNLMS" is used instead). Coast Guard vessels are given the prefix "KV" for KystVakt (Coast Watch) in Norwegian and permissibly, and less ambiguously in English, are styled "NoCGV", Norwegian Coast Guard Vessel.

History

The history of Norwegian state-operated naval forces is long, and goes back to the leidang which was first established by King Håkon the Good at the Gulating in 955, although variants of the Leidang had at that time already existed for hundreds of years. During the last part of the Middle Ages the system of levying of ships, equipment, and manpower for the leidang was mainly used to levying tax and existed as such into the 17th Century.

During most of the union between Norway and Denmark the two countries had a common fleet. This fleet was established by King Hans in 1509 in Denmark. A large proportion of the crew and officers in this new Navy organisation were Norwegian. In 1709 there were about 15,000 personnel enrolled in the common fleet; of these 10,000 were Norwegian. When Tordenskjold carried out his famous raid at Dynekil in 1716 more than 80 percent of the sailors and 90 percent of the soldiers in his force were Norwegian. Because of this the Royal Norwegian Navy shares its history from 1509 to 1814 with the Royal Danish Navy.

The modern, separate Royal Norwegian Navy was founded (restructured) on April 12, 1814, by Prince Christian Fredrik on the remnants of the Dano-Norwegian Navy. At the time of separation, the Royal Dano-Norwegian Navy was in a poor state and Norway was left with the lesser share. All officers of Danish birth were ordered to return to Denmark and the first commander of the Norwegian navy became Captain Thomas Fasting. It then consisted of 39 officers, seven brigs (one more under construction), one schooner-brig, eight gun schooners, 46 gun chalups and 51 gun barges.[4] April 1, 1815, the Royal Norwegian Navy's leadership was reorganized into a navy ministry, and Fasting became the first navy minister.

Norway retained its independent armed forces, including the navy, during the union with Sweden. During most of the union the navy was subjected to low funding, even though there were ambitious plans to expand it. In the late 19th century, the fleet was increased to defend a possible independent Norway from her Swedish neighbours.

In 1900, just five years prior to the separation from Sweden, the navy, which was maintained for coastal defense, consisted of: two British-built coastal defence ships (HNoMS Harald Haarfagre and HNoMS Tordenskjold – each armored and displacing about 3,500 tons), four ironclad monitors, three unarmored gun vessels, twelve gunboats, sixteen small (sixty ton) gunboats, and a flotilla of twenty-seven torpedo boats.[5] These were operated by 116 active duty officers (with an additional sixty reserve) and 700 petty officers and seamen.[6]

Norway was neutral during World War I, but the armed forces were mobilised to protect Norway's neutrality. The neutrality was sorely tested – the nation's merchant fleet suffered heavy casualties to German U-boats and commerce raiders.

World War II began for the Royal Norwegian Navy on April 8, 1940, when the German torpedo boat Albatross attacked the guard ship Pol III. In the opening hours of the Battle of Narvik, the old coastal defence ships ("panserskip") HNoMS Eidsvold and HNoMS Norge, both built before 1905 and hopelessly obsolete, attempted to put up a fight against the invading German warships; both were torpedoed and sunk. The German invasion fleet heading for Oslo was significantly delayed when Oscarsborg Fortress opened fire with two of its three old 28 cm guns, followed by the 15 cm guns on Kopås on the eastern side of the Drøbak strait. The artillery pieces inflicted heavy damage on the German heavy cruiser Blücher, which was subsequently sunk by torpedoes fired from Oscarsborg's land-based torpedo battery. Blücher sank with over 1,000 casualties among its crew and soldiers aboard. The German invasion fleet – believing Blücher had struck a mine – retreated south and called for air strikes on the fortress. This delay allowed King Haakon VII of Norway and the Royal family, as well as the government, to escape capture.

On June 7, 1940, thirteen vessels, five aircraft and 500 men from the Royal Norwegian Navy followed the King to the United Kingdom and continued the fight from bases there until the war ended. The number of men was steadily increased as Norwegians living abroad, civilian sailors and men escaping from Norway joined the Royal Norwegian Navy. Funds from Nortraship were used to buy new ships, aircraft and equipment.

Ten ships and 1,000 men from the Royal Norwegian Navy participated in the Normandy Invasion in 1944.

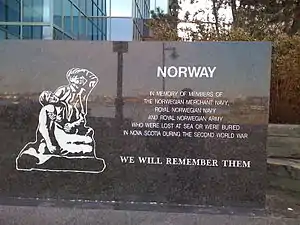

During the war the navy operated 118 ships, at the end of the war it had 58 ships and 7,500 men in service. They lost 27 ships, 18 fishing boats (of the Shetland bus) and 933 men in World War II.[7]

The navy had its own air force from 1912 to 1944.

The building of a new fleet in the 1960s was made possible with substantial economic support from the United States. During the cold war, the navy was optimized for sea denial in coastal waters to make an invasion from the sea as difficult and costly as possible. With that mission in mind, the Royal Norwegian Navy consisted of a large number of small vessels and up to 15 small diesel-electric submarines. The navy is now replacing those vessels with a smaller number of larger and more capable vessels.

The Royal Norwegian Navy Museum is dedicated to the preservation and promotion of Norway's naval history.

Ensign and Jack

Naval Ensign 1814–1815

Naval Ensign 1814–1815.svg.png.webp) Naval Ensign 1815–1844

Naval Ensign 1815–1844

(during Union with Sweden, also used by the Swedish Navy).svg.png.webp) Naval Ensign 1844–1905

Naval Ensign 1844–1905

(during Union with Sweden) Naval Ensign since 1905

Naval Ensign since 1905.svg.png.webp) Naval Jack 1844–1905

Naval Jack 1844–1905

(during Union with Sweden, also used by the Swedish Navy) Naval Jack since 1905

Naval Jack since 1905

Bases

Some of The Royal Norwegian Navy's bases are:

- Haakonsvern, Bergen (main base for the navy).

- Ramsund, between the towns of Harstad and Narvik (special operations/Marinejegerkommandoen)

- Trondenes Fort, Harstad (Coastal Ranger Command)

- Sortland (Coast Guard Squadron North)

- Karljohansvern, Horten (training facility)

Organization

The Navy is organized into the Fleet, the Coast Guard, and the Naval Schools. The Fleet consists of:

- Fleet Chief Staff,

- Frigate Branch (Fregattvåpenet),

- Submarine Branch (Ubåtvåpenet),

- MTB Branch (MTB-våpenet),

- Mine Branch (Minevåpenet)

- Norwegian Special Warfare Group (Marinens jegervåpen)

- Logistics Branch (Logistikkvåpenet).

The Naval Schools are:

- Royal Norwegian Naval Basic Training Establishment, KNM Harald Haarfagre, Stavanger

- Royal Norwegian Navy Officer Candidate School, Horten and Bergen

- Royal Norwegian Naval Academy, Laksevåg, Bergen

- Royal Norwegian Naval Training Establishment, KNM Tordenskjold, Haakonsvern, Bergen

Two of the schools of the Navy retain ship prefixes, reminiscent of Royal Navy practises.[8]

Museum: Royal Norwegian Navy Museum, Horten

Fleet units and vessels (present)

.jpg.webp)

Submarine Branch

The submarine fleet consists of several Ula class submarines.

"Ubåtvåpenet" maintain six Ula class submarines:

Frigate Branch

NOTE: These ships are generally considered destroyers by their officers and other navies due to their size and role.[9] F313 Helge Ingstad is no longer in use as a collision with an oil tanker sank the ship off the coast of Norway.

- Fridtjof Nansen-class frigate. Five vessels commissioned. Four currently in service.

- Fridtjof Nansen (F310) Launched June 3, 2004. Commissioned April 5, 2006.

- Roald Amundsen (F311) Launched May 25, 2005. Commissioned May 21, 2007.

- Otto Sverdrup (F312) Launched April 28, 2006. Commissioned April 30, 2008.

- Helge Ingstad (F313) Launched November 23, 2007. Commissioned September 29, 2009. Sunk

- Thor Heyerdahl (F314) Launched February 11, 2009. Commissioned January 18, 2011.

- Royal yacht:

MTB Branch

_(2_Nov_2001).jpg.webp)

The Coastal Warfare fleet consists of Skjold class Corvettes.

- Missile Patrol Boat (Skjold class, all 6 commissioned:

- Skjold (P960) Launched September 22, 1998. Commissioned April 17, 1999

- Storm (P961) Launched November 1, 2006.

- Skudd (P962) Launched April 30, 2007.

- Steil (P963) Launched January 15, 2008.

- Glimt (P964)

- Gnist (P965)

Mine Branch

- 1st Mine Clearing Squadron

- Oksøy-class mine hunter (1994)

- Oksøy M340

- Karmøy M341

- Måløy M342

- Hinnøy M343

- Oksøy-class mine hunter (1994)

- Alta-class minesweeper (1996):[10]

- Alta M350

- Otra M351

- Rauma M352

- Orkla M353 (Ship sunk on 19 November 2002)

- Glomma M354

- Alta-class minesweeper (1996):[10]

- Naval EOD Commando

- Gnist (P965)

Norwegian Navy Special Warfare Group

- Coastal Ranger Command

- Norwegian Naval EOD Commando

- Tactical Boat Squadron

- Combat Boat 90N (1996)[11]

- Trondenes

- Skrolsvik

- Kråkenes

- Stangnes

- Kjøkøy

- Mørvika

- Kopås

- Tangen

- Oddane

- Malmøya

- Hysnes

- Brettingen

- Løkhaug

- Søviknes

- Hellen

- Osternes

- Fjell

- Lerøy

- Torås

- Møvik

- Combat Boat 90N (1996)[11]

Marinejegerkommandoen (MJK) – Norwegian maritime special operations forces unit

Logistics Branch

- Supply ship HNoMS Maud. Acquired in November 2018 and expected full operating capability (FOC) in autumn 2021.[14]

- Royal yacht:

- Safeguard ship for specialforces

2 Dockstavarvet AB type IC20M Interceptor ( Two delivered as of December 16, 2015. One option ) [15]

- August Nærø

- Petter B Salen

Coast Guard units and vessels

Future vessels

HNoMS Maud, a Logistic Support Vessel, was ordered in 2013 for NOK 1320m (~US$230m).[16] It is to AEGIR 18 design based on the British Tide-class tanker of BMT but built by Daewoo, entering service 2017–18. The 26,000 t vessel will allow replenishment at sea of fuel, munitions and some solid stores, as well as having hospital facilities.[17] It has a helicopter hangar with two bays for NH-90 helicopters or future drones; technical facilities, workshops and supplies for heavier helicopter maintenance/repair than aboard frigates. It is built with CIWS (Close In Weapon Systems) against airborne threats and Kongsberg Aerospace and DefenceSea Protector RWS (Remote Weapon Stations), a cannon, as well as the ability to modify the weapons suite for the operations required; there are also machine gun positions and two riveted boarding/man overboard vessels plus ample room on board for the protection force and transients. Multiple systems for self defence and link up with LINK-16 permits patrol duties when underway, or such as a continuing role. Norwegian NH-90 helicopters can be within 2 hours kitted out with the Coast Guard Kit (e.g. for rescues) or Frigate Kit (for ASW & ASuW, Anti Surface Warfare and Anti Submarine Warfare). When time or planning permits the latter this frees the ship for secondary tasks from reconnaissance to medical evacuations and foreign-soil emergency planning. In December 2019, Maud was banned from sailing after global risk-assessment firm DNV GL revealed several safety hazards, deeming the vessel too unsafe to sail.[18] These problems were expected to be tackled in early 2020 so that the vessel could enter full operational service. However, as of August 2020, the ship only began initial testing to return to full operational service which is now projected for mid-2021.[19]

Norway has also prioritized replacing its current submarine fleet. In February 2017 the German manufacturer Thyssen Krupp was selected to deliver four new submarines, based on the Type 212-class, in around 2030 [20] to replace the Ula-class boats. A firm build contract with Thyssen Krupp was anticipated in the first half of 2020 as part of a joint program under which Norway will procure four submarines and Germany two.[21][22][23] However, as of the end of 2020 a contract had not yet been signed.

The Coast Guard is to replace its existing Nordkapp-class vessels with significantly larger ice-capable ships, each displacing just under 10,000 tonnes. The three new Jan Mayen-class ships will be armed with a 57mm main gun and be capable of operating up to two NH-90 helicopters. The vessels are to enter service between 2022 and 2025.[24]

The 2020 Norwegian defence plan envisages the replacement of the current major surface vessels "after" 2030. Decisions concerning type and number of vessels are to be "made in the next planning period".[25]

Insignia

| NATO code | OF-10 | OF-9 | OF-8 | OF-7 | OF-6 | OF-5 | OF-4 | OF-3 | OF-2 | OF-1 | OF(D) | Student officer | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No equivalent |  |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

No equivalent | |||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Admiral | Viseadmiral | Kontreadmiral | Flaggkommandør | Kommandør | Kommandørkaptein | Orlogskaptein | Kapteinløytnant | Løytnant | Fenrik | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| NATO Code | OR-9 | OR-8 | OR-7 | OR-6 | OR-5 | OR-4 | OR-3 | OR-2 | OR-1 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Sjefsmester | Flaggmester | Orlogsmester | Flotiljemester | Skvadronmester | Senior Kvartermester | Kvartermester | Ledende Konstabel | Konstabel | Senior Visekonstabel | Visekonstabel | Ledende menig | Menig | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

References

Footnotes

- The Military Balance 2013 (2013 ed.). International Institute for Security Studies. 14 May 2013. pp. 160–162. ISBN 978-1857436808.

- Helle, 1995, p. 196.

- "The Navy – Mil.no". Archived from the original on 29 November 2014. Retrieved 14 December 2014.

- "Den norske Marine i 1814". Retrieved 14 December 2014.

- Keltie, J.S., ed. The Stateman's Year Book: Statistical and Historical Annual of the States of the World for the Year 1900. New York: MacMillan, 1900. p 1066. (Retrieved via Google Books 3/5/11.)

- Keltie 1900, p. 1067.

- Berg, Ole F. (1997). I skjærgården og på havet – Marinens krig 8. april 1940 – 8. mai 1945 (in Norwegian). Oslo: Marinens krigsveteranforening. p. 154. ISBN 82-993545-2-8.

- "Fact sheet from Department of Defense". odin.dep.no. Archived from the original on 25 April 2006. Retrieved 27 March 2018.

- "U.S. Studies Norwegians For Manning Mindset". aviationweek.com. Retrieved 19 March 2016.

- "Kongsberg to Supply MINESNIPER Mk III Mine Disposal Weapon System to Royal Norwegian Navy". September 20, 2013.

- "The Royal Norwegian Navy is acquiring Navigation Equipment Package for Combat Boat 90". November 23, 2013.

- Ole H. Nissen-Lie (Båtliv). "Norske kjøremaskiner vekker oppsikt". VG. Retrieved 19 March 2016.

- "Goldfish med 10 RIB-båter til forsvaret". Norsk Maritimt Forlag – Båtliv.no. 12 February 2009. Archived from the original on 27 February 2015. Retrieved 19 March 2016.

- https://www.tu.no/artikler/knm-maud-klarer-ikke-a-utfore-sin-viktigste-oppgave-ma-repareres-i-nederland/501775

- Jan Einar Zachariassen. "August Nærø". skipsrevyen.no. Archived from the original on 16 March 2016. Retrieved 19 March 2016.

- "Inngår kontrakt om nytt logistikkfartøy" (in Norwegian). Skipsrevyen. 28 June 2013. Archived from the original on 10 May 2017. Retrieved 5 April 2016.

- "Saab receives design and integration orders for healthcare capability for Norwegian support vessel". Skipsrevyen. 7 October 2014. Retrieved 5 April 2016.

- "KNM Maud får seilingsforbud etter avvik" (in Norwegian Bokmål). ABC Nyheter. 2019-12-19. Retrieved 2019-12-25.

- https://www.tu.no/artikler/to-ar-etter-leveransen-er-problemskipet-knm-maud-ute-pa-provetur/497402

- https://www.regjeringen.no/contentassets/3a2d2a3cfb694aa3ab4c6cb5649448d4/long-term-defence-plan-norway-2020---english-summary.pdf

- https://www.defensenews.com/global/europe/2019/04/30/german-norwegian-officials-huddle-over-joint-submarine-program/

- "Norway Looks South in Search of Arctic-Class Submarine Builder". defensenews.com. 8 August 2017. Retrieved 27 March 2018.

- Tran, Pierre (8 August 2017). "Losing vendor in Norway sub deal hopes for another chance". defensenews.com. Retrieved 27 March 2018.

- https://blogs.cardiff.ac.uk/arctic-relations/2019/06/13/recent-developments-in-arctic-maritime-constabulary-forces-canadian-and-norwegian-perspectives/

- https://www.regjeringen.no/contentassets/3a2d2a3cfb694aa3ab4c6cb5649448d4/long-term-defence-plan-norway-2020---english-summary.pdf

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Royal Norwegian Navy. |

- Official website of the Royal Norwegian Navy Archived 2019-06-02 at the Wayback Machine (in Norwegian)

- English, Official site (in English)

- Royal Norwegian Navy, Equipment Facts (in English)

- Facts & Figures: The Royal Norwegian Navy (Norwegian Defence – Official Website) (in English)

- Befalsbladet 1/2004 (in Norwegian)

- Royal Norwegian Navy history page (in Norwegian)

- Another Royal Norwegian Navy History page (in Norwegian)

- Royal Norwegian Navy Museum web page (in Norwegian)

- Royal Norwegian Navy Museum web page at mil.no (in Norwegian)

- Fakta om Forsvaret 2006, issued January 2006 by the Ministry of Defense, ISBN 978-82-7924-058-7

- Helle, 1995, p. 196.