Chenoprosopus

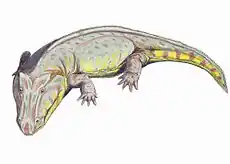

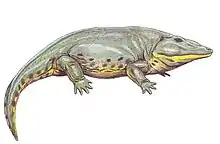

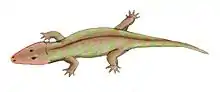

Chenoprosopus is a genus of extinct cochleosauridae that lived during late Carboniferous and early Permian periods.[1] Two known species of Chenoprosopus are C. milleri and C. lewisi. Chenoprosopus lewisi was described in the basis of a virtually complete skull with maximum skull length of 95 mm.[2] It is significantly smaller than Chenoprosopus milleri and was differentiated from that taxon by Hook (1993) based on sutural patterns of the skull roof. Hook also mentioned the reduced size of the vomerine tusks differentiated C. lewisi from C. milleri, but the different size of these tusks may be different ontogenetic stages of growth.[2] Many of other cochleosaurids from the same time period have an elongated vomer and wide and elongate choana.[3] However, Chenoprosopus is distinguished by its more narrowly pointed snout and separation between the nasal from the maxilla by the broad lacrimal-septomaxilla contact.[2]

| Chenoprosopus | |

|---|---|

| |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | |

| Phylum: | |

| Class: | |

| Order: | |

| Family: | |

| Genus: | Chenoprosopus |

| Type species | |

| Chenoprosopus milleri Mehl,1913 | |

| Synonyms | |

|

Chenoprosopus lewisi Hook, 1993 | |

The Chenoprosopus name means as “goose short face” based on Greek cheno as a goose[4] and prosopus as a short face.[5]

Description and paleobiology

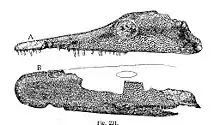

The skull of Chenoprosopus measures from 95 mm to 305 mm length from the tip of the snout to the back of the skull. The pineal foramen is present skull of over 120 mm length.[2][6] Analysis of the remains is inhibited because, although the anterior third and the left side to the median line are complete, the loss of the upper posterior border of the skull (prevents us from understanding something about the critter). Fragments from the right are so badly crushed and so incomplete that they are little use to determine the position of the teeth. However, the skull of Chenoprosopus is distorted and slightly compressed laterally and much of the sutures and pitting is not disturbed.[1]

The Chernoprosopus was a carnivore. Mehl suggested that Chenoprosopus fed on soft organisms such as worms and the larvae of large insects of its time.[6] There are several indications that suggest Chenoprosupus had a terrestrial life. Mehl states that the laterally directed orbits of Chenoprosopus is strongly suggestive of its terrestrial life.[6] Also, the absence of lateral line sulci on the roof of the skull and the well ossified qualities of the postcranial skeleton also support the notion that they had a terrestrial life.[7] The primitive tetrapod, Acanthostega gunnari (Jarvik, 1952), presents a direct biting of prey feeding mechanism and demonstrates the terrestrial mode of feeding.[7] Unlike most terrestrial feeders among temnospondyli, Chenoprosopus, which lived in dry environments, displayed weaker bite capabilities than Nigerpeton, which presents strong bite capabilities.[7] The skull of Chenoprosopus presented stresses in the posterior part of the skull than in the rest of the skull because of weak bite capabilities that could be the adductor musculature beneath the squamosal bones.[7]

Skull

The skull is long and narrow broadly rounded anteriorly with the sides diverging slightly and regularly in the anterior four-fifths of the length. The orbit of Chenoprosopus milleri is nearly round and is about 32 mm. in diameter.[6] It is smaller than Nigerpeton ricqlesi.[8] The orbits are positioned midway along the skull length and widely spaced. The plane of the orbit is parallel with the lateral margin of the skull and is directed out and slightly upward. The orbit depression extends back and slightly down for a short distance from the middle of the posterior border and lies a little behind the naris and in a line with the orbit and the naris. The naris has a rounded and is approximately 10 mm wide and 7 mm long. The shape of nasals are large, rectangular, and about three times as long as wide. It is placed near the lateral margin of the skull and about 50 mm behind the tip of the rostrum. Its plane is directed out and upward. The otic notch is deep, open fully posteriorly and separated from the supratemporal and squamosal. The jugal is a large element extending from the anterior border of the orbit back at least as far as the ear opening. The upper side of the quadrate is thin, with plate-like bone extending up and forward as if to connect with the skull just above the otic notch. The septomaxillae are small, triangular elements, fully twice as long as wide, and form nearly the entire posterior border of the naris. It extends back between the nasals and the maxilla, but are apparently separated from the lachrymals by a considerable space.[2]

The premaxilla of Chenoprosopus number approximately 20 (Hook, 1993)[8] and have a short contact with the maxilla at the skull margin.[2] The maxilla is excluded from the narial opening by the septomaxilla. The bases of the maxillary teeth are placed closely to the external margin of the maxilla. The estimated minimum number of maxillary tooth positions is 34. The first two maxillary teeth are smaller than the adjacent position of the premaxillary dentition tooth size. These teeth have relatively narrow, round bases, recurved distal halves, and sharply pointed ends. Also, the maxilla is excluded from the narial opening by the septomaxilla. A short maxilla-nasal suture is evident on both sides of the skull, followed by contacts with the lacrimal and jugal.[2]

Palate

Palate is flat and an elongated choana that nearly reaches the level of the anterior limit of the interpterygoid vacuities. The lateral margin of the choana is not exposed, the opening lacks the anterior expansion and a round shape. Anterior palatal fossil occurs on the vomers as modest concavities separated by a thin longitudinal septum. The conjoined palatines and pterygoids are broad and have a long, comparatively narrow interpterygoid vacuity. The posterior processes of the pterygoids are curved inward to join the quadrate. The posterior pterygoid process extends upward in a thin plate, including a large infra-temporal vacuity. The length of each interpterygoid vacuity is approximately three times greater than its width, or equal to about a third of the skull length. The interpterygoid vacuities set back in posterior half of skull. The vacuities widen and become broadly rounded near the level of the basal process. Small ossicles filling the interpterygoid vacuity indicate there was a plate of denticles in the vacuities. (cite Montanari). The vomerin tusks are larger and placed in a more lateral position. At the posterolateral margin of the choana, a second palatal tusk is present on the palatine and is accompanied by a replacement pit; the basal diameter of this tusk is slightly greater than that of the largest maxillary tooth.[2][6]

Discovery

The cochleosaurid amphibian Chenoprosopus was discovered in El Cobre Canyon Formation near the Miller bone bed in the vicinity of Arroyo del Agua, north-central New Mexico[9] by Mr. Paul C. Miller and established as a new genus based on an incomplete skull by Mehl in 1913.[6] The skull was long and narrow, 28 cm (11.0 in) long and 5.4 cm (2.1 in) wide. The teeth were stout and conical, slightly recurved and about 19 mm (0.7 in) long. A single vertebra was also found at the site and this resembled the vertebrae of Diadectes.[6] Chenoprosopus lewisi was described by Hook, 1993, from the Permo-Carboniferous Markley Formation in Texas.[10]

Classification

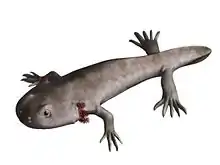

Chenoprosopus belongs to clade Edopoidea, a superfamily of temnospondyl. Edopoidea has several primitive characteristics of temnospondyls. These are namely the retention of intertemporal ossification, and the palatine rami of the pterygoids meeting anteriorly to exclude the palatines and vomers from the interpterygoid vacuity margins.[3]

References

- Reisz, R.R. (2005). "A New Skull of the Cochleosaurid Amphibian Chenoprosopus (Amphibia: Temnospondyli) from the Early Permian of New Mexico". New Mexico Museum of Natural History and Science Bulletin No. 30

- Hook, Robert (1993). "Chenoprosopus lewisi, A New Cochleosaurid Amphibian (Amphibia: Temnospondyli) from the Permo-Carboniferous of North-Central Texas". Annals of Carnegie Museum. 62: 273–291.

- Milner, Andrew (1998). "A Cochleosaurid Temnospondyl Amphibian from the Middle Pennsylvanian of Linto, Ohio, USA". Zoological Journal of the Linnean Society. 122 (1–2): 261–290. doi:10.1006/zjls.1997.0121.

- Brown, Roland (1954). Composition of Scientific Words. Washington. p. 16025.

- "Paleofile".

- Mehl, M. G. (1913). A description of Chenoprosopus milleri. Publications of the Carnegie Institute, Washington, 186, 11-16.

- Fortuny, J (2011). "Temnospondyli bite club: ecomorphological patterns of the most diverse group of early tetrapod". Journal of Evolutionary Biology. 24 (9): 2040–2054. doi:10.1111/j.1420-9101.2011.02338.x. PMID 21707813.

- Steyer, J (2006). "The Vertebrate Fauna of the Upper Permian of Niger. IV. Nigerpeton Ricqlesi (temnospondyli: Cochleosauridae), and the Edopoid Colonization of Gondwana". Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology. 26: 18–28. doi:10.1671/0272-4634(2006)26[18:tvfotu]2.0.co;2.

- Berman, David. "Pennsylivanian-Permian Red bed Vertebrate localities of New Mexico and Their Assemblages". Vertebrate Paleontology in New Mexico. 68: 65–68.

- Lucas, Spencer (2005). "Early Permian Vertebrate Biostratratigraphy at Arroyo del Agua, Rio Arriba County, New Mexico". New Mexico Museum of Natural History and Science Bulletin. 31: 163–169.